Abstract

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) represents one of the strongest predictors of progression to AIDS, yet it is difficult for most patients to sustain high levels of adherence. This study compares the efficacy of a personalized cell phone reminder system (ARemind) in enhancing adherence to ART versus a beeper. Twenty-three HIV-infected subjects on ART with self-reported adherence less than 85% were randomized to a cellular phone (CP) or beeper (BP). CP subjects received personalized text messages daily; in contrast, BP subjects received a reminder beep at the time of dosing. Interviews were scheduled at weeks 3 and 6. Adherence to ART was measured by self-report (SR, 7-day recall), pill count (PC, past 30 days at baseline, then past 3 weeks), Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS; cumulatively at 3 and 6 weeks), and via a composite adherence score constructed by combining MEMS, pill count, and self report. A mixed effects model adjusting for baseline adherence was used to compare adherence rates between the intervention groups at 3 and 6 weeks. Nineteen subjects completed all visits, 10 men and 9 females. The mean age was 42.7 ± 6.5 years, 37% of subjects were Caucasian and 89% acquired HIV heterosexually. The average adherence to ART was 79% by SR and 65% by PC at baseline in both arms; over 6 weeks adherence increased and remained significantly higher in the ARemind group using multiple measures of adherence. A larger and longer prospective study is needed to confirm these findings and to better understand optimal reminder messages and user fatigue.

Introduction

Lack of adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) is one of the strongest predictors of progression to AIDS and death among persons living with HIV.1–3 Studies suggest that adherence to ART varies by regimens. For instance, non-boosted protease inhibitor (PI) containing regimens have been shown to require adherence rates greater than 95% for optimal viral suppression while newer regimens such as boosted PIs or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors are more forgiving if occasional doses are missed.4–6 Forgetfulness has been identified as a major barrier to ART adherence, leading to a number of studies testing reminder devices such as pagers, alarms and telephones.7–11 Although a recent systematic review did not show sufficient evidence to support the use of electronic reminder devices to enhance adherence to ART, it did highlight the need for rigorous controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of such devices.12

Cellular telephones are daily-use devices that can become powerful electronic reminder systems. Their popularity in the American household has grown exponentially over the past few years, such that in 2008 there were 87 mobile subscriptions per 100 households.13 As such, they demonstrate a ubiquity, accessibility, and familiarity for patients that could make long-term use more sustainable over other electronic devices, such as beepers.14 They are convenient and inconspicuous reminder devices that allow varying degrees of dynamic individualization depending on patient preferences, and are currently being tested to promote various health behaviors in developed and developing countries.15–19 In a pilot study, Puccio et al.20 reported that the use of cellular phone reminders was practical and acceptable in a group of 8 HIV-infected young adults, but viral suppression waned for most subjects after termination of the 12-week intervention; moreover, no objective measure of adherence was utilized. Efficacy studies using cellular phones to enhance adherence are limited, however a growing body of evidence seems to show that their use in chronic diseases is promising.21–23

The overall objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of customized dynamic reminder messages sent via a cellular phone-based reminder system (ARemind) to motivate and track adherence to ART in HIV/AIDS subjects and to compare the efficacy of this system to a standard beeper reminder. The rationale for comparing these two interventions is to learn whether long-term interventions can depend on patients' existing cell phones, instead of dedicated beeper devices, and also to examine whether the dynamic content provided by cell phone messages is beneficial in reducing user fatigue. We conducted a two-phase study in which adherence to ART was measured using multiple methods. The first phase consisted of qualitative key informant interviews to evaluate the content and usability of ARemind messages. The second phase included a 6-week feasibility study in which subjects were randomized to either the ARemind cellular phone or beeper arm.

Methods

Participants and study setting

The study took place from August 2008 to December 2008 in an outpatient HIV clinic located within a large teaching hospital in Boston (Boston Medical Center, BMC). The clinic serves a diversity of HIV-infected subjects, including a high proportion of females and minorities. Subjects were HIV-infected men and women receiving HIV primary care in the clinic and were recruited through flyers posted in the clinic and followed-up between August 2008 and October 2008.

Procedures

Subjects were recruited and screened by a HIV specialty pharmacist at the clinic. Eligibility criteria included being English-speaking, HIV-infected, at least 18 years old, on a stable regimen of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for at least 3 months, and reporting less than 85% adherence to ART over the prior 7 days. Participants were purposefully identified in order to obtain a representative cross-section of clinic subjects in terms of age, race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, education, level of adherence, substance use/abuse history. The Institutional Review Board at Boston University Medical Center approved the study. There were two phases of the study: a key informant interview (Phase 1) and a feasibility study (Phase 2).

Phase 1

Eight subjects participated in qualitative individual key informant interviews over a 2-week period during the summer of 2008. Each subject received a $40 incentive for their time. The objectives of these interviews were: (1) to allow the participants to evaluate content of the planned text messages to be sent via the ARemind prototype and (2) for the research team to assess the ability of potential participants to use the cellular phone technology in preparation for a test of the cellular phones as adherence reminder tools. Following administration of the informed consent, each participant responded to a series of questions administered by a member of the study team that addressed three content areas: (1) health and hiv information, (2) experience with cellular phones and other relevant technology, and (3) preferred content of reminder text messages. The interviewer took notes throughout the interview to document responses. Based on what we learned in the patient interviews, we made adaptations for the Phase 2 feasibility study.

Phase 2

In Phase 2, twenty-three HIV-infected subjects meeting the inclusion criteria were randomized (1:1) using a parallel study design to use either a cellular phone (ARemind-CP group, n = 12) or one-way pager/beeper (BP group, n = 11). The randomization was conducted by the team statistician who had no contact with study subjects; a randomization list was generated and provided to the clinical investigators who used it to assign each subjects to an intervention arm. Each subject received a $30 incentive per study visit ($90 total). The main objectives of the feasibility study were: (1) to assess whether subjects with HIV/AIDS could use ARemind-CP for a sustained period; (2) to compare Aremind-CP efficacy to enhance adherence against a one-way beeper alarm system; and (3) to inform the design of a future larger randomized trial. Key informant interviews were also conducted at each study visit to assess prior experience with cell phone and text messaging, utility of the reminder device to take medications, utility of text messages to communicate with the treating physician, and issues related to content and to texting/responding back.

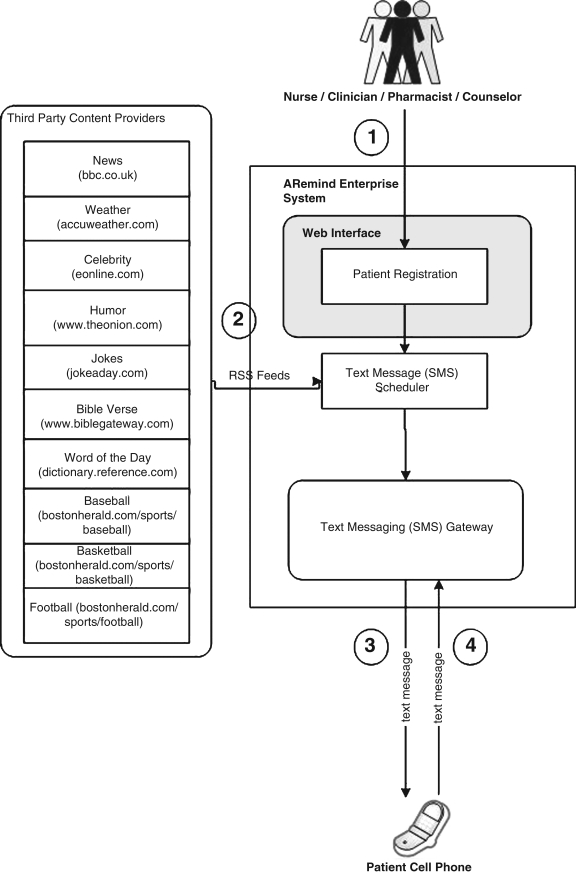

Subjects randomized to the ARemind-CP each received one Samsung A930 flip phone with an unlimited calling and texting plan. Even though some of the subjects had phones already, phones were supplied so that we could ensure that they remained active over the course of the study and so that we would not have to store personally-identifying information such as the patient's personal cell phone number. The subjects in this arm were assigned a number of daily reminder events matching their ART dosing frequency. They received personalized text messages and had to respond with a text message when taking ART. Figure 1 provides a diagram of the ARemind server and its features.

FIG. 1.

Overview of ARemind 1 System. To begin, a caregiver registers a patient's mobile number, content preference, and dosing schedule in the system (1). At the scheduled time, the scheduler pulls fresh content from third party content providers (2), then generates a text message which is sent to the patient (3). The patient responds to the text message indicating that they have taken their medication (4).

The content of each reminder message was linked to an Internet-accessible feed of information pulled via a Really Simple Syndication (RSS) aggregator. Topics were drawn from our findings from Phase 1, and feed sources were selected from the same categories and links published by leading web content providers, Yahoo and MSN. For example, The Onion provided a “jokes” feed, Accuweather provided a “weather” feed, and so forth. Consequently, content of reminders could include popular news, sports, weather information, and other timely information. Participants chose one of the following categories at the time of their enrollment: news, weather, celebrity news, humor, jokes, Bible verses, word of the day, baseball, basketball, or football. They could select a different category during the study visits at week 3 and 6, although only 2 chose to do so. Upon receipt of the reminder message, the participant was instructed to respond with an SMS in order to confirm that they were taking their medication; any text message received was considered a valid response. If they did not respond, the phones used had a built-in feature which would beep every 15 min until the patient pressed a button on the phone acknowledging receipt of the message.

Subjects randomized to the beeper arm received an ALRT Med Reminder device, which would beep at the time they were expected to take their ART dose. The devices would beep once for 30 seconds, and would not repeat if the reminder was not acknowledged. The time of the reminder beep was set by the investigator at the time of the participant's enrollment in the study and was chosen with the participants' input based on their daily existing ART dosing schedule. There was no tapering of the reminders (SMS from CP or beep from ALRT Med Reminder device) during the course of the study. We felt that at this stage of the research we needed to focus on the impact of the tailored messages and the differences in medication taking behavior between the two arms rather than adjusting the frequency of the reminders based on each patient's adherence level given the short duration of the study. There were no medication changes made for the purpose of the study and interviews were scheduled at weeks 3 and 6.

At the end of each study visit, the subjects in both arms were asked to answer a few questions administered by a member of the study team that addressed six areas: (1) prior experience with cell phone/beeper and text messaging (only asked at baseline visit); (2) use of reminder devices to take medications; (3) device usability and friendliness; (4) issues related to texting/responding back; (5) comments about the technology; (6) interest in continued use of device. The interviewer took notes throughout the interview to document responses.

Outcome measures

Adherence to ART during Phase 2 was measured by self-report (SR, 7-day recall), pill count (PC, past 30 days at baseline, then past 3 weeks), and Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS; cumulatively at 3 and 6 weeks). Participants were asked to bring their bottles of antiretrovirals at each study visit. A PC was performed by counting the pills remaining in the bottles and calculating percent adherence as: (number of prescribed doses – number of missed doses)/number of prescribed doses. All subjects received a MEMS cap at entry in the study. As done by Miller et al.,24 the MEMS cap was placed on the bottle containing the protease inhibitor if the patient was taking such a regimen or on the bottle with the most frequently dosed medication if the patient was not taking a protease inhibitor.

Previous studies have shown that available adherence measures have limitations, raising questions about how best to measure drug-taking behavior; consequently, we decided to use a composite adherence score (CAS) to measure more objectively adherence rates in our small cohort.25 The calculation of the CAS was based on a method previously described by Liu and colleagues.25

Since MEMS is recognized as being the most accurate of the three adherence measures (MEMS, pill count, and self report) it was used as the foundation for CAS. The following steps were followed to construct CAS:

Use MEMS whenever deemed accurate (i.e. any MEMS adherence rate < 100%), otherwise.

-

When MEMS not accurate,

If PC available, use a predicted MEMS count based on a calibration model built using the PC adherence and MEMS; otherwise

If SR available use a predicted MEMS count based on a calibration model built using the self reported adherence and MEMS; otherwise

CAS is set to missing.

Following Liu et al.,25 calibration models used to predict MEMS adherence based on PC and SR adherence were constructed using linear mixed effect models. For example, in constructing the calibration model for PC, time and PC were included in the model as fixed effects, while the subject specific intercepts were included as a random. A similar approach was used to construct the calibration model for SR adherence. The analyses yielded following calibration equations.

|

(M1) |

|

(M2) |

Statistical tests for intercept and time coefficient in both model M1 and M2 did not reach significance (p values were 0.18 and 0.29, 0.84, and 0.44, respectively); however, coefficients for PC and SR adherence were highly significant (p-values were <0.0001 and 0.0002, respectively).

Statistical methods

Phase 1—Qualitative analysis

Key informant interview data were analyzed using standard qualitative analytic techniques. The result of each interview was typed for analysis as word processing text files suitable for manipulation using qualitative software and entered into the qualitative software program (HyperRESEARCH version 8.2) The data were analyzed and the content grouped into four general categories: background and demographic information, health and HIV information (daily medication intake routine, beliefs about ART, social support, adherence barriers), experience with cell phones and other technology (frequency of use, experience texting, opinion about privacy and security of phones), and preferences for text message content (news, sports, jokes, Bible verse, quotations, weather, etc).

Phase 2—Quantitative analysis

All quantitative analyses were carried out using SAS 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Bivariate analyses comparing the two interventions (Aremind-CP versus BP) were performed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. Pearson correlation was used to assess relationship between the results based on the different measures of adherence. Adherence (measured as MEMS, PC, SR, and CAS) differences between the two treatment groups at 3 and 6 weeks were assessed by repeated measures analysis. A linear mixed effects model was fit to the data. The subject specific intercepts were included as a random effect while baseline PC adherence, group assignment, time, and their interaction were also included as fixed effects in the model. The covariance for each participant at different time points was modeled by an unstructured matrix (In SAS, ID was specified as the subject in the repeated statement of MIXED procedure). The adherence results of Aremind-CP users were compared with those of beeper users by computing the differences in least squares means of adherence at the second (3 week) and third interview (6 week). We compared changes in adherence from the second to the third interview for each group (cell phone and beeper users) using the same methods. Response behavior to reminders over time within the cell phone group was studied using generalized estimating equations (GEE) models. Time was the only explanatory variable. The outcome variables were proportion sent response after reminder, proportion opened medication bottle after reminder, proportion sent response and opened medication bottle, proportion sent response but did not open medication bottle, and proportion did not send response but opened medication bottle. The covariance for each participant at different time points was modeled by a compound symmetrical matrix (ID was again specified as the subject in the repeated statement of GENMOD procedure).

Results

Description of participants

Phase 1

The demographics of the subjects enrolled in Phase 1 are summarized in Table 1. Questions about health and HIV information showed that 3 subjects reported taking ART once a day while 5 took it twice a day. Most subjects (7/8) felt extremely positive about their HIV treatment and considered ART to be a life saver. All admitted missing doses of ART “here and there” and the main barriers to adherence included forgetfulness, busy schedule, and being away from home. Questions addressing level of experience with cellular phone and other technology showed that 50% of the subjects were currently cellular phone users and 7 of 8 had experienced using a cellular phone. Only 2 of 8 subjects, however, had experience with text messages; 4 were interested in learning how to text and 2 subjects were not interested in a cellular phone texting feature at all. When addressing the type of content subjects would like to receive as medication reminders, all subjects stated that they would not want a message including the word “HIV medication,” There was a wide array of answers regarding the content of the reminder messages illustrating the importance of being able to personalize the reminder message. Overall, the areas of preferences included sports, news, weather, entertainment, Bible verse and jokes.

Table 1.

Results of the Phase 1 Informant Interviews

| Variables | Results |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range) | 50.5 (35–69) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 6 |

| Female | 2 |

| Race | |

| Black | 6 |

| Causasian | 1 |

| Latino | 1 |

| Education | |

| >High school degree | 8 |

Phase 2

Table 2 summarizes the demographics of the 23 subjects enrolled in this phase. Of the 23 subjects enrolled in Phase 2, 4 subjects (2 in control group and 2 in intervention group) were lost to follow-up and were excluded from analyses. A total of 10 subjects in the ARemind-CP arm and 9 subjects in the BP arm (10 males and 9 females) completed the study. Overall, 10 subjects were taking a twice a day ART and 9 subjects were on a once daily regimen. The randomization resulted in two balanced groups with the only imbalance being on the adherence barrier “fear of side effects.” Of the 9 subjects enrolled in the beeper group, all reported fear of side effects to be a significant barrier to adherence; in contrast, 4 of 10 (40%) subjects in the ARemind-CP arm reported this to be a significant adherence barrier to ART (p = 0.001).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Subjects in Phase 2

| Patient characteristics | Cell phone | Beeper | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male, n | 5 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Female, n | 5 | 4 | |

| Age, yrs (±SD) | 42 ± 8 | 44 ± 4 | 0.592 |

| Race | |||

| White, % | 50 | 22 | 0.536 |

| Employed, % | 20 | 22 | 1.0 |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| MSM | 10 | 11 | |

| Heterosexual | 90 | 89 | 1.0 |

| HIV disease diagnosis, years | 14 ± 5 | 14 ± 9 | — |

| Mental health comorbidities, % | 70 | 89 | 0.582 |

| Baseline HIV labs | |||

| Viral load | 30,920 ± 97,525 | 9,352 ± 21,836 | 0.526 |

| CD4 count | 378 ± 324 | 281 ± 159 | |

| Antiretroviral therapy (%) | |||

| Once daily dosing | 50 | 44 | 0.99 |

| Twice daily dosing | 50 | 56 | |

SD, standard deviation; MSM, Men who have sex with men.

Evaluation of intervention Effects (Phase 2)

Table 3 provide a summary of the adherence rates measured in the study population at various times points. At baseline, prior to randomization, all of the 19 enrolled subjects had adherence measured by PC (mean ± standard deviation [SD]; 64.6% ± 26.7) and SR (79.1% ± 21.3); there was no significant difference in adherence measured by either method, p = 0.92 and p = 0.36, respectively (Table 3). The two measures of adherence were found to be moderately correlated r = 0.46 (p = 0.07).

Table 3.

Comparison of Mean Percent Adherence Between the Cellular Phone and Beeper Arms at Week 3 and Week 6a

| Adherence method | Baseline | Week 3 | p Value | Week 6 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS | |||||

| Overall | 72.0 (59.3–84.8) | 73.9 (60.7–87.1) | |||

| CP | 85.3 (70.7–99.9) | 89.7 (76.5–102.9) | |||

| BP | 57.2 (41.8–72.7) | 56.3 (42.4–70.3) | |||

| Difference | 28.1 (6.8–49.4) | 0.0129 | 33.4 (14.1–52.6) | 0.002 | |

| (CP-BP) | |||||

| Pill Count | |||||

| Overall | 64.6 (51.8–77.5) | 69.1 (58.2–80.0) | 76.3 (66.4–86.1) | ||

| CP | 65.2 (46.9–83.5) | 76.5 (62.5–90.6) | 82.7 (68.7–96.8) | ||

| BP | 64.0 (44.7–83.3) | 60.8 (46.0–75.7) | 69.1 (54.2–83.9) | ||

| Difference | 1.2 (−25.4–27.8) | 15.7 (−4.7–36.1) | 0.1442 | 13.7 (−6.7–34.1) | 0.1529 |

| (CP-BP) | |||||

| Self-report | |||||

| Overall | 79.1 (68.8–89.3) | 85.3 (76.1–94.6) | 83.1 (70.4–95.7) | ||

| CP | 83.4 (69.1–97.7) | 91.1 (79.7–102.5) | 92.6 (77.5–107.7) | ||

| BP | 74.2 (59.2–89.2) | 78.9 (66.9–90.9) | 72.4 (56.5–88.3) | ||

| Difference | 9.2 (−11.5–29.9) | 12.2 (−4.3–28.8) | 0.1367 | 20.2 (−1.8–42.1) | 0.0689 |

| (CP-BP) | |||||

| CAS | |||||

| Overall | 69.7 (58.1–81.4) | 70.6 (58.6–82.5) | |||

| CP | 81.5 (67.8–95.1) | 83.4 (70.0–96.9) | |||

| BP | 56.7 (42.3–71.1) | 56.3 (42.2–70.4) | |||

| Difference | 24.8 (4.9–44.7) | 0.0176 | 27.1 (7.6–46.6) | 0.0094 | |

| (CP-BP) | |||||

MEMS, Midication Event Monitoring System; CP, cell phone; BP, beeper; CAS, composite adherence score.

At week 3, all subjects had measured adherence by MEMS in addition to PC and SR. CAS adherence scores were computed using the algorithm described in the method section. Adherence measured by PC and SR increased relative to baseline to 69.1% ± 22.6 and 85.3% ± 19.2, respectively. The MEMS and CAS adherence was estimated to be 72.0% ± 26.4 and 69.7% ± 24.1, respectively. Not surprisingly, the SR provided the highest estimate of adherence. The correlation among the four measures ranged from 0.50 to 0.97, all of the correlations were statistically significant. The highest correlation was found between MEMS and CAS (MEMS is the foundation of CAS), the second highest was between PC and MEMS (r = 0.74, p < 0.001), and the smallest detected correlation was between PC and SR (r = 0.50, p = 0.03). Significant differences between the mean adherence of the two intervention groups (Aremind-CP or BP) were found when adherence was measured by MEMS (mean difference ± SD: 28.1 ± 10.0, p = 0.012) and CAS (24.8 ± 9.4, p = 0.018); significance was not attained when assessing differences between the mean adherence as measured by PC (15.7 ± 10.2, p = 0.144) or SR (12.2 ± 7.8, p = 0.137).

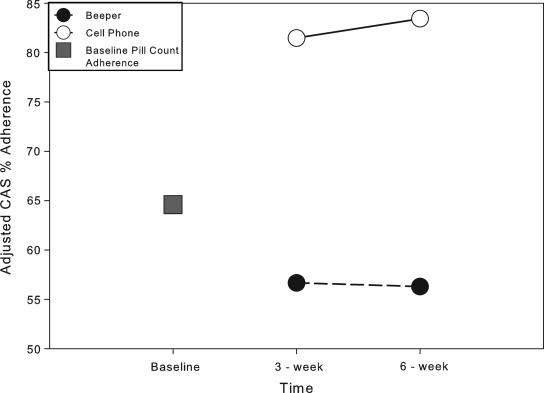

At week 6, all subjects had measured adherence by MEMS in addition to PC and SR. CAS adherence scores were computed using the same algorithm described in the method section. Adherence measured by PC, SR, MEMS and CAS were 76.3% ± 20.5, 83.1% ± 26.2, 73.9% ± 27.3 and 70.6% ± 24.8, respectively. There was a slight increase in adherence rates from the week 3 values in all methods but SR, which decreased slightly (Table 3). SR provided the highest estimate of adherence. The correlation among the four measures ranged from 0.63 to 0.95; all of the correlations were statistically significant. The highest correlation was again found between MEMS and CAS, the second highest was between PC and CAS (r = 0.74, p < 0.001), and the smallest correlation was between MEMS and SR (r = 0.63, p < 0.001). Significant differences between the mean adherence of the two intervention groups were found when adherence was measured by MEMS (mean difference ± [SD]: 33.4 ± 9.1, p = 0.002) and CAS (27.1 ± 9.2, p = 0.009). Figure 2 presents the differences in adherence noted over time between BP and CP arms when using CAS. Significance was not attained when assessing differences between the mean adherence measured by PC (13.7 ± 9.1, p = 0.153) or SR (20.2 ± 10.3, p = 0.069).

FIG. 2.

Composite adherence score (CAS) over time by intervention group. Closed circle: Adjusted composite adherence score (%) for subjects randomized to the beeper arm. Open circle: Adjusted composite adherence score (%) for subjects randomized to the cellular phone arm. Closed square: Baseline adjusted adherence rate calculated via pill count; d: difference in composite adherence score between the beeper arm and cellular phone arm.

Missing Adherence data

In Phase 2, there were 4 subjects lost to follow-up (2 in CP group, 2 in BP group) who had their adherence measures missing at week 3 and week 6. For these subjects, the CAS was set to missing for the main analysis. The significance of the group comparison results held true even when including the above 4 subjects with the CAS adherence levels to 30%. In five instances (three at the 3-week interview and two at the 6-week interview) the calculated MEMS percent adherence was greater than 100%. These values were imputed with the predicted values based on a calibration model as described in the Methods section. Since both the PC and SR percent adherence were available for all subjects, the calibration model based on PC was used. We assessed the sensitivity of the results to the imputed values using a simulation study. Ten thousand samples were generated from the predictive distributions of each 5 MEMS adherence values that were deemed inaccurate based on the calibration models. For each sample the mean adherence difference between the two intervention arms and p-values for no treatment effect at week 3 and week 6 were generated. All of the samples resulted in a significant difference between the mean adherence in the two intervention groups at both week 3 and week 6 (p value ranges: 0.004–0.043 at week 3 and 0.004–0.026 at week 6). The ranges for the estimated mean adherences were 20.8–27.6 at week 3 and 23.3–30.1 at week 6. Thus, we are confident of a significant result and robust differences in adherence of as high as 20.8 at week 3 and 23.3 at week 6.

Results on sustainability of ARemind use in HIV/AIDS subjects

Sustainability was measured as the rate of response to the text messages, since this is an indication that the patients are continuing to use the application. Results on sustainability of ARemind are summarized in Table 4. We compare response rates during the first three weeks of Phase 2 of the study (weeks 0–3) with the last three weeks (weeks 3–6) of Phase 2. Data was drawn from all users of the ARemind system who did not drop out (ten subjects in total). No response rates to reminders sent via beeper were assessed since the beeper did not have this capability. During the first 3-week period, there were 10 to 41 text reminders sent per patient depending on the dosing frequency of the HIV regimen prescribed. The median response rate during this time was 0.78. During the second 3-week period (weeks 3–6), there were 15 to 44 text reminders sent per patient. The median response rate during this time was 0.62. To account for within-patient correlation we used the generalized estimation equation (GEE) model.

Table 4.

Odds Ratios for Selected Behaviors by Subjects in Cellular Phone Arm by GEE Model

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Responding to reminder: week 6 vs. week 3 | 0.51 (0.27–0.94) | 0.0323 |

| MEMS after reminder: week 6 vs. week 3 | 0.73 (0.50–1.07) | 0.1109 |

| Response sent and MEMS after reminder: week 6 vs. week 3 | 0.70 (0.41–1.21) | 0.1980 |

| Response sent but no MEMS after reminder: week 6 vs. week 3 | 0.60 (0.44–0.81) | 0.0009 |

| MEMS but no response sent after reminder: week 6 vs. week 3 | 1.12 (0.73–1.71) | 0.6073 |

GEE, generalized estimating equations; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; MEMS, Medication Event Monitoring System.

The model showed that the odds of a patient sending a response message after a reminder dropped by a factor of 0.51 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.27–0.94). Looking at the rate in which patients responded to the text message and also took their medication (as recorded by the MEMS), we did not find significant differences between week 0–3 and week 3–6 (p = 0.198). The odds of medication use after a reminder dropped by a factor of 0.73 (95%CI 0.50–1.07) in the week 3 to week 6 period. However, the odds of not taking the medication after sending a response to the reminder did decrease significantly (p = 0.0009) by a factor of 0.6 over the course of the study (95% CI 0.44–0.81). Interestingly, the actual medication use measured by MEMS after receipt of a text reminder did not change significantly between week 3 and week 6. Consequently, although we did observe a decrease in sending response text messages over time (perhaps secondary to user fatigue), this decrease was not associated with a decrease in adherence to ART.

Qualitative findings of Phase 2

Overall, the content of the medication reminder messages sent to patients did not matter for most patients. Indeed, 9 of 10 participants reported that they enjoyed receiving a content-tailored reminder text message, but only 1 participant, whose content was Bible verses, said that the content helped motivate her in some way to take the medications. All participants said that having a reminder “ring back” until they texted back was what mattered as a reminder. The majority of patients also considered the devices (cellular phone or beeper) easy to use. When subjects were asked if they would continue using a program like ARemind to help them take ART as prescribed and to communicate with their physician, most said they would, but stated they would not be able to text regularly on a cellular phone due to out-of-pocket expenses associated with a texting plan. A third of the subjects assigned to the beeper did not think it was a useful tool to use to help enhance and/or sustain adherence, and most thought it could trigger curiosity from people around them (friends, family) and indirectly violate their confidentiality since they found themselves in situations where they had to explain why they carried a beeper.

Discussion

Electronic reminder devices (ERD), including cellular phones, are growing in popularity as aides for patients who take frequent medications. Few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of such tools in a controlled manner and adherence to therapy has most commonly been measured using self-report.10,17,19 To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial of a personalized cellular phone reminder system (ARemind) to show a significantly better short term improvement in adherence to ART in comparison to a beeper reminder system. Our study has several important implications. First, similar to others studying the acceptance of cellular phones in healthcare, our qualitative findings suggest that ARemind was well accepted and practical.21,23 Second, the average adherence to ART, which was low at baseline (79% by self-report and 65% by PC) in both arms was shown to increase in the ARemind group over the 6-week follow-up period with multiple measures of adherence (MEMS, CAS, PC). Increased adherence rates have been observed with pager systems over short period of time (i.e., ≤2 weeks), but they are rarely sustained over long periods of time. Safren et al.26 noted improvements in MEMS adherence rates from baseline (55%) to week 2 (70%) in subjects using a one-way pager device, but this increase was not sustained and by week 12 had decreased to 64%. In a large interventional, randomized clinical trial of HIV-infected patients using a two-way pager system, Simoni et al.12 found that both self-report and perfect MEMS adherence (i.e., 100%) decreased over time in subjects using the two-way pager (64% of subjects reported 100% adherence at week 2 and 49% at 3 months compared to 63% at week 2 via MEMS and to 44% at 3 months).

Our study was shorter in duration than these two studies, yet the positive and statistically significant differences observed with the various measures of adherence between the two groups at week 3 and 6 is promising. Third, the ARemind system provided subjects with scheduled reminders that only stopped once a response was acknowledged. This particular function of the system was identified as a factor fostering adherence in the qualitative portion of the study. The quantitative findings of our study support the idea that MEMS use was sustained over time (p = 0.198) despite changes in response rates to reminders. A 12% increase in MEMS use was noted between week 3 to week 6 despite a lack of response to text reminders and a 40% decrease in response to text reminder without MEMS use was observed during this same period. Possible explanations for this behavior may be that since cellular phones are part of most people's daily life and are used for many purposes besides adherence reminders, repetitive reminders are not perceived as intrusive as reminders sent by a system solely dedicated to medication reminders like a pager. Finally, although most of our subjects stated that the content of messages did not matter to them—it is possible that the tailoring of the content to the patients' interests may have participated in sustaining their motivation in taking medications over time.

There were several limitations to the present study. First, our sample size was small and no clinical outcome data was collected (i.e., viral load, CD4 count), limiting the generalizability of our results. Second, our follow-up study period was only 6 weeks, precluding any assessments of long-term changes in medication taking behavior. Third, the content of the messages was based on patient preferences for light and engaging material such as jokes, weather, and sports or other news. It is possible that the addition of educational content to improve health literacy could further improve adherence. Fourth, the ARemind phone reminders repeated every 15 min until they were attended to while the beepers would not repeat after the intended time. We do not have data on how many reminders patients using ARemind heard before attending to their phones—this represents a possible bias relating to the intervention.

In an upcoming study, we plan to assess the impact that various message contents may have on patients' motivation to take ART, the impact of the frequency of reminders and text responses on adherence as well as on user fatigue.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the patients who participated to this research project, Verizon Wireless for generously providing the cellular phones utilized by the patients during this study, the National Institute of Mental Health who provided the funding for the SBIR (1R43MH080655-01A1)

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Nachega JB. Hislop M. Dowdy DW. Chaisson RE. Regensberg L. Maartens G. Adherence to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based HIV therapy and virologic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:564–573. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross R. Yip B. Lo Re V, 3rd, et al. A simple, dynamic measure of antiretroviral therapy adherence predicts failure to maintain HIV-1 suppression. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1108–1114. doi: 10.1086/507680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramadhani HO. Thielman NM. Landman KZ, et al. Predictors of incomplete adherence, virologic failure, and antiviral drug resistance among hiv-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1492–1498. doi: 10.1086/522991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paterson DL. Swindells S. Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in subjects with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:942–944. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shuter J. Forgiveness of non-adherence to HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:769–773. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nieuwkerk PT. Sprangers MA. Burger DM, et al. Limited patient adherence to highly activeantiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection in an observational cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1962–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills EJ. Nachega1 JB. Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HAART: A systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. Plos Med. 2006;3:2039–2064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrade AS. McGruder HF. Wu AW, et al. A programmable prompting device improves adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected subjects with memory impairment. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:875–882. doi: 10.1086/432877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunbar PJ. Madigan D. Groshskopf LA, et al. A two-way Messaging System to Enhance Antiretroviral Adherence. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10:11–15. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan WA. Can the ubiquitous power of mobile phones be used to improve health outcomes in developing countries? Global Health. 2006;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simoni JM. Huh D. Frick PA, et al. An RCT of peer support and pager messaging to promote antiretroviral therapy adherence and clinical outcomes among adults initiating or modifying therapy in Seattle, WA, United States. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2009;52:465–473. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181b9300c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database. http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/ [Jul 9;2010 ]. http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/statistics/

- 14.Wise J. Operario D. Use of electronic reminder devices to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: A systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22:495–504. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim MS. Hocking JS. Hellard ME. Aitken CK. SMS STI: A review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:287–290. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lester JL. Cell-phone medicine brings care to patients in developing nations. Health Affairs. 2010;29:259. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lester RT. Mills EJ. Kariri A, et al. The HAART cell phone adherence trial (WelTel Kenya1): A randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials. 2009;10:87–97. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brianna S. Fjeldsoe BA. Alison L, et al. Behavior change interventions delivered by mobile telephone short-message service. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waller A. Pagliari C. Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:1332–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puccio J. Belzer M. Olson J, et al. The use of cell phone reminder calls for assisting HIV-infected adolescents and young adults to adhere to highly active antiretroviral therapy: A pilot study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20:438–444. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vidrine DJ. Arduino RC. Lazev AB, et al. A randomized trial of proactive cellular phone intervention for smokers living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2006;20:253–260. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198094.23691.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marciel KK. Saiman L. Quittell LM, et al. Cell phone intervention to improve adherence: Cystic fibrosis care team, patient, and parent perspectives. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:157–164. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ybarra ML. Bull SS. Current trends in Internet- and cell phone-based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller LG. Liu H. Hays RD, et al. How well do clinicians estimate patients' adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.09004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu H. Golin CE. Miller LG, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:968–977. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-10-200105150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safren SA. Hendriksen ES. Desousa N, et al. Use of an online pager system to increase adherence to antiretroviral medications. AIDS Care. 2003;15:787–793. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001618630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]