Abstract

Background

Previous studies have found that up to 15% of clinical encounters are experienced as difficult by clinicians.

Objectives

Explore patient and physician characteristics associated with being considered “difficult” and assess the impact on patient outcomes.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Participants

Seven hundred fifty adults presenting to a primary care walk-in clinic with a physical symptom.

Main Measures

Pre-visit surveys assessed symptom characteristics, expectations, functional status (Medical Outcome Study SF-6) and the presence of mental disorders [Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders, (PRIME-MD)]. Post-visit surveys assessed satisfaction (Rand-9), unmet expectations and trust. Two-week assessment included symptom outcome (gone, better, same, worse), functional status and satisfaction. After each visit, clinicians rated encounter difficulty using the Difficult Doctor-Patient Relationship Questionnaire (DDPRQ). Clinicians also completed the Physician’s Belief Scale, a measure of psychosocial orientation.

Key Results

Among the 750 subjects, 133 (17.8%) were perceived as difficult. “Difficult” patients were less likely to fully trust (RR = 0.88, 95% CI: 0.77–0.99) or be fully satisfied (RR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.62–0.98) with their clinician, and were more likely to have worsening of symptoms at 2 weeks (RR = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.57–0.97). Patients involved in “difficult encounters” had more than five symptoms (RR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3–2.3), endorsed recent stress (RR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.4–3.2) and had a depressive or anxiety disorder (RR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.3–4.2). Physicians involved in difficult encounters were less experienced (12 years vs. 9 years, p = 0.0002) and had worse psychosocial orientation scores (77 vs. 67, p < 0.005).

Conclusion

Both patient and physician characteristics are associated with “difficult” encounters, and patients involved in such encounters have worse short-term outcomes.

Studies have consistently shown that clinicians experience up to 15% of patient encounters as “difficult.”1,2 Most previous studies have focused on patient characteristics of difficult encounters, finding that somatizing patients2–6 and those with underlying mental disorders, poor functional status, greater symptom severity or high utilizers of health care services1–6 are more likely to be perceived as difficult. Only three studies have examined physician factors. Difficulty has been associated with younger physicians, those with greater stress, heavier workloads or symptoms of depression or anxiety,7 having perfectionistic tendencies and a desire to be liked,8 and having poor lower pyschosocial orientation.

While there is a rich literature discussing the “difficult” patient, much of it in the form of essays, there is less written about the “good” patient. Lorber wrote that a “good” patient is one without psychosocial issues presenting with an acute biomedical disease that is easily diagnosed and responds to treatment.9 In comparison, “difficult” patients appear to have multiple unexplained physical symptoms that tend to be unresponsive to treatment.

A few studies have examined outcomes from difficult encounters, finding that patients in difficult encounters have greater post-visit unmet expectations and lower satisfaction.1,5,6 Providers are more likely to report higher rates of burnout and job dissatisfaction.7 In this study we sought to build on previous literature by developing a fuller model of difficult encounters, using both patient and clinician factors. A secondary goal was to assess the outcomes of “difficult” encounters.

METHODS

Adults (>18 years old) presenting to an internal medicine acute care walk-in clinic at Walter Reed Army Medical Center with a chief complaint of a physical symptom were eligible to participate. This clinic provides both primary care and urgent care for enrolled beneficiaries. Patients were not seeing their regular clinicians and could follow up with the acute-care clinician, though most were referred back to their primary care clinician for follow-up. Urgent care patients are triaged, and those deemed acutely ill are referred to the emergency room. We selected this clinic for two reasons: (1) to obtain lower levels of satisfaction and (2) to reduce the selection that occurs both by patients and providers in established patient-clinician dyads. This design helps to hold patient and clinician characteristics and interactions constant, allowing isolation of differences between physicians. We excluded patients with dementia. We have previously shown that the demographics (age and gender), mix of medical problems, proportion of patients with depressive, anxiety and somatization disorders, functional status and proportion considered “difficult” in this clinic are similar to those found in US non-federal ambulatory practices.1,10–12 Participants were similar to non-participants in terms of age, race, sex and type of presenting symptoms. Patients were enrolled between 2005–2007. Our Institutional Review Board approved this study, and all patients and providers provided informed consent.

PRE-VISIT ASSESSMENT

Immediately prior to their visit, subjects were evaluated for (1) mental disorders [Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD)13], a validated structured psychiatric interview, (2) demographics, (3) symptom characteristics [type of symptom, duration of symptom (days) and severity (0, none to 10, unbearable)], (4) recent stress (yes/no) and (5) symptom-specific visit expectations, (6) functional status [Medical Outcomes Study short form 6 (MOS SF-6)14] and (7) somatization [Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15)].13 The MOS SF6 measures functional status in six domains: general health, role functioning, physical functioning, social functioning, emotional functioning and physical pain. Each question has a five-item Likert-type score, except for pain, which has six options, yielding a range in scores from 6–31.The PHQ-15 asks patients how much they’ve been bothered by 15 common ambulatory symptoms in the 2 weeks prior to the visit.

POST-VISIT ASSESSMENT

Immediately post-visit, patients were surveyed for (1) satisfaction (RAND-9),14 (2) whether or not they were still worried their symptom could be serious (yes/no), and (3) whether or not they had any unmet expectations. The RAND-9 is an instrument that asks nine Likert-style questions on satisfaction. Because we were interested in immediate post-visit satisfaction with the clinician the patients saw, we limited the analysis to the five questions focusing on satisfaction with the clinician (overall satisfaction, satisfaction with bedside manner, with explanation of what was done, with time spent with clinician and with thoroughness of clinician) rather than the system. These five questions yielded a score from 5 to 25.

Two weeks after the visit, patients completed a questionnaire that assessed (1) symptom outcome, (2) symptom severity (0–10), (3) stress in the previous 2 weeks (yes/no), (4) functional status (MOS SF-6), (5) overall satisfaction and (6) the presence of any unmet expectations. Six-month health utilization before the index visit was obtained from the electronic medical record.

PHYSICIAN ASSESSMENT

Providers completed the Physician Belief Scale15, which measures psychosocial orientation and has previously been found to correlate with a more patient-centered communication style15 and lower malpractice claim rates.16 The Physician Belief Scale consists of 38 questions, and scores greater than 70 suggest a poor psychosocial orientation. Immediately after each visit, clinicians completed the Difficult Doctor Patient Relationship Questionnaire (DDPRQ), a ten-item instrument that measures how difficult the encounter was from the provider’s perspective. The DDPRQ is scored from 10–60, with scores greater than 30 considered to reflect a “difficult” encounter. This instrument has been found to be valid and reliable.3

ANALYSIS

Analyses were done using STATA (version 9.2, College Station, Texas) or AMOS (SPSS v. 4.0, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were analyzed using analysis of variance or covariance, standard linear regression or the Kruskall-Wallis as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed using Mantel-Haenszel or logistic regression. Model fitting and variable selection as well as interaction and confounding assessment followed the methods of Hosmer and Lemeshow.17

We have previously been able to achieve high levels of follow-up by: (1) stressing the importance of follow-up, (2) by initially contacting patients via a personalized, specific (chief complaint, date of visit, name of clinician seen) letter in a self-addressed, stamped envelope (73% response rate), (3) sending a second letter, increasing the yield to 81%, and (3) phone calls.

We calculated sample sizes from previous data showing that 15% of patients were considered difficult in this clinic and that walk-in patients reported experiencing 2-week symptom resolution 45% of the time. Based on an alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.8, a sample size of 728 subjects would allow us to show a 33% difference in symptom resolution between “difficult” and “not difficult” patients. Given previous high levels of 2-week follow-up, we collected a sample of 750 adults presenting to an acute-care walk-in clinic.

STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELING

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess the web of interactions and relationships between patient and clinician characteristics, and encountered difficulty. Traditional multivariable methods allow researchers to assess direct relationships between dependent and independent variables. SEM models allow researchers to tease out both direct and indirect effects and give a clearer picture of the interactions between the various influences on the outcome of interest. A direct effect is a relationship between two variables. An indirect effect is an effect one variable has on another that is mediated by an intermediate variable. For example, functional status has a direct effect on satisfaction; patients with poorer functional status are less satisfied. On the other hand, mental disorders reduce functional status, which in turns reduces satisfaction; mental disorders indirectly affect satisfaction. A total effect is calculated by combining a specific variable’s direct and indirect effects.18 In developing the SEM models, we sought to develop the best-fitting, most parsimonious model possible by selecting potential variables for inclusion in our SEM model based on two criteria: (1) previous literature and (2) univariate screening including potential variables with p < 0.25, though no non-plausible variables were included. SEM model fit was tested using the ratio of chi-square to the degrees of freedom (CMIN), the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), the root mean square error of analysis (RMSEA)19 and the Hoelter’s “critical N.”20 SEM models are considered to be well fitted when the CMIN is less than 3, the AGFI is greater than 0.9, the RMSEA is less than 0.05, and the Hoelter’s critical N is greater than 20020,21. We used standardized estimates of effect, since the different variables had different scaling, to allow comparison of strength of effect between the independent variables.22 If the influence of variable A on variable B is 0.25, that means for every 1 standard deviation of increase in variable A, variable B increases by 0.25 standard deviations. We omitted variable error estimations from the SEM figures to make the figures visually simpler. The full model, with error terms, is available by contacting the second author (JLJ).

RESULTS

We enrolled 750 adults and were able to attain 2-week follow-up in 724 (96%). Participants averaged 53.6 years in age, 52% were female, 47% Caucasion and 44% African American (Table 1). Subjects presented with a variety of symptoms, with more than half endorsing some form of pain, and 41% reporting symptom severity of 6 or greater on a 0–10 scale. The most common complaints were gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal. Half of the patients had experienced their symptom for less than 2 weeks and 22% less than 3 days. In addition to the presenting complaint, patients reported, on average, 3.2 other “currently bothersome” physical symptoms. Seventy-one percent of patients had three or more expectations for the encounter; 43% reported stress within the preceding week, and 29% had an underlying mental disorder (8% major depression, 5% generalized anxiety disorder and 2% panic disorder).

Table 1.

Patient and Clinician Characteristics

| Patient characteristic | Overall n = 748 | Difficult N = 100 | Not difficult N = 648 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 53.3 | 56.3 | 52.9 | 0.11 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male, % | 359 (48%) | 39 (11%) | 320 (89%) | 0.09 |

| Female | 389 (52%) | 62 (16%) | 327 (84%) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 352 (47%) | 60 (17%) | 292 (83%0 | 0.49 |

| Black | 329 (44%) | 36 (11%) | 293 (89%0 | |

| Other | 67 (9%) | 9 (14%) | 58 (86%) | |

| Education | ||||

| College | 314 (42%) | 41(13%) | 273 (87%) | 0.98 |

| High school | 411 (55%) | 53(13%) | 358 (87%) | |

| Less than HS | 22 (3%) | 3 (15%) | 19 (85%) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Divorced | 187 (25%) | 17 (29%) | 170 (91%) | 0.05 |

| Married | 352 (47%) | 16 (14%) | 302 (86%) | |

| Single | 90( 12%) | 73 (20%) | 72 (80%) | |

| Widowed | 75 (10%) | 16 (21%) | 59 (79%) | |

| Symptom characteristics | ||||

| Duration (median) | 14 | 21 | 14 | 0.08 |

| Severity (0–10) | 5.6 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 0003 |

| Worried symptom might be serious | 455 (63%) | 75 (75%) | 380 (61%) | 0.004 |

| Number of “other” bothersome symptoms (PHQ 15) mean, (SD) | 4.0 | 5.5 | 3.7 | <0.0005 |

| Mental disorders, n (%) | ||||

| Sub-threshold depression | 90 (12%) | 21 (21%) | 69 (11%) | 0.04 |

| Major depression | 60 (8%) | 13 (13%) | 47 (7%) | 0.03 |

| Anxiety not otherwise specified | 75 (10%) | 18 (18%) | 5 (9%) | 0.004 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 15 (2%) | 6 (6%) | 9 (1%) | 0.001 |

| Panic disorder | 15 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 13 (2%) | 0.64 |

| Multi-somatoform disorder | 135 (18%) | 27 (27%) | 108 (17%) | 0.03 |

| Endorses recent stress, % | 299 (40%) | 39 (39%) | 260 (41%) | 0.70 |

| Functional status (6–31), mean (SD) | 22.7 (5.2) | 20.6 (5.4) | 23.0 (5.1) | <0.00005 |

| Clinician characteristics (n = 38) | ||||

| Male | 307 (41%) | 47 (15%) | 260 (85%) | 0.41 |

| Female | 441 (59%) | 53 (13%) | 388 (87%) | |

| Physician belief score 0- | 68.7 | 72.9 | 67.2 | <0.00005 |

| Clinician type | ||||

| Staff general internist | 411 (55%) | 30 (9%) | 381 (93%) | 0.10 |

| Internal medicine house staff | 337 (45%) | 57 (17%) | 280 (83%) | |

| Years of practice | ||||

| <10 years | 232 (31%) | 23 (9%) | 209 (77%) | <0.00005 |

| 11–20 years | 456 (61%) | 13 (3%) | 443 (87%) | |

| >20 years | 60 (8%) | 2 (3%) | 58 (98%) | |

Participants were seen by 38 different clinicians: 59% of these clinicians were women; 55% were internal medicine residents, though staff clinicians saw the majority of patients (55%). On average, staff clinicians saw 34 participants (range 2–34), while house staff saw 9 subjects (range 1–13). Participating staff clinicians averaged 16 years of experience (range 4–28). There was no difference in the age (p = 0.63), gender (p = 0.42), ethnicity (p = 0.39), education (p = 0.43), number of symptoms (p = 0.28), presence of mental disorders (p = 0.98) or any other baseline patient characteristic between patients seen by staff or residents.

CHARACTERISTICS OF DIFFICULT ENCOUNTERS

One hundred thirty-three encounters (17.8%) were perceived as difficult by the providers. A number of patient and physician characteristics were associated with difficulty (Table 2). Patients had more symptoms (5.5 vs. 3.7, p < 0.005), reported greater symptom severity (6.3 vs. 5.4, p = 0.002), had worse functional status (20.6 vs. 23.1, p < 0.005) and were more likely to have an underlying mental disorder (23% vs. 15%, p < 0.0005). More experienced clinicians reported a lower proportion of encounters as difficult; clinicians with less than 10 years of practice experienced 23% of encounters as difficult, compared to 2% among clinicians with more than 20 years of practice. Physicians with poor scores (greater than 70) on the Physician Belief Scale experienced more encounters as difficult (23% vs. 8%, p < 0.00005).

Table 2.

Patient and Clinician Predictors of Difficulty

| Patient predictors | |||

| Characteristic | Difficult | Not difficult | P |

| Symptom severity | 6.3 | 5.4 | 0.002 |

| Number of Symptoms | 5.5 | 3.7 | <0.005 |

| Functional status | 20.6 | 23.1 | <0.005 |

| Mental disorder | 28% | 15% | <0.0005 |

| Multi-somatoform disorder | 21% | 11% | 0.02 |

| Pre-visit serious illness worry | 21% | 13% | 0.005 |

| Clinician predictors | |||

| Characteristic | Difficult | Not difficult | P |

| Physician Belief Scale (PBS) | 77.2 | 67.7 | 0.005 |

| Years MD | 9.2 | 12.3 | 0.0002 |

OUTCOMES FROM “DIFFICULT” ENCOUNTERS

Being involved in a “difficult” encounter was associated with a number of adverse outcomes (Table 3). Patients were more likely to have unmet expectations immediately after the visit (RR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.3–3.2) and at 2 weeks (RR = 1.6, 95% CI = 2.1–3.1), and were less likely to fully trust (RR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.77–0.99) or be fully satisfied with the clinician they saw (immediately after the visit: RR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.62–0.98; 2 weeks later: RR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.57–0.97, Table 4). Over the 2 weeks of follow-up, patients from “difficult” encounters were more likely to experience worsening of their presenting symptom (RR = 2.4, 95% CI = 1.3–4.5) and had higher 6-month utilization rates (7.3 vs. 4.7, p < 0.00005).

Table 3.

Patient Outcomes from Difficult Encounters

| Outcome measures | Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Patient trust | 0.88 (0.77–0.99) |

| Fully satisfied | |

| Immediately post-visit | 0.78 (0.62–0.98) |

| 2 weeks after index visit | 0.75 (0.57–0.97) |

| Unmet expectations | |

| Immediately post-visit | 2 (1.3–3.2) |

| 2-week follow-up | 1.6 (2.1–3.1) |

| Symptom worse at 2 weeks | 2.4 (1.3–4.5) |

Table 4.

Independent Predictors of Difficulty

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| >5 somatic symptoms on presentation | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) |

| Report of increased stress in preceding week | 1.9 (1.4–3.2) |

| Presence of depression or anxiety disorder | 2.3 (1.3–4.2) |

PREDICTORS OF DIFFICULTY

On multivariable modeling, patients involved in difficult encounters were more likely to have more than five somatic symptoms at presentation (RR: 1.81, 95% CI = 1.3–2.3), more likely to report increased stress during the preceding week (RR: 1.9, 95% CI = 1.4–3.2) and to have a depressive or anxiety disorder (RR: 2.3, 95% CI = 1.3–4.2) (Table 4). The physicians involved in the difficult encounters were more likely to have fewer years of practice (p = 0.0002) and to score poorly on the Physician Belief Scale (p < 0.005). We found no interaction among clinician and patient age, gender or ethnicity (Table 5).

Table 5.

Standardized Indirect, Direct and Total Effects

| Indirect effect | Direct effect | Total effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severity | 0.27 | NA | 0.27 |

| Number of psychiatric disorders | 0.09 | NA | 0.15 |

| Symptom count (PHQ15) | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.19 |

| Utilization rate | NA | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Functional status | NA | -0.12 | -0.12 |

| Expectations | NA | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Physician Belief Score | NA | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Years MD | -0.07 | NA | -0.02 |

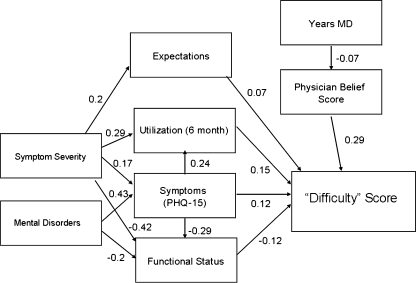

On SEM modeling both clinician and patient factors contributed directly and indirectly to encounter difficulty (Fig. 1). The indirect, direct and total effect of each variable on encounter difficulty is given in Table 3. Patient factors that directly increased difficulty were having a greater number of expectations, higher utilization, a greater number of bothersome symptoms and worse functional status directly. For example, every 1 standard deviation of increase in the number of physical symptoms increased the difficulty score by 0.12 standard deviations. Symptom severity and the number of underlying psychiatric disorders had indirect effects on the difficulty score. For example, mental disorders increased somatization (by 0.43 standard deviations) and decreased functional status by 0.2 standard deviations. The net effect of mental disorders was to increase difficulty by 0.15 standard deviations. Physician characteristics that contributed to the difficulty score included their Physician’s Belief Score and number of years of clinical practice. The Physician’s Belief Score had a direct effect on the difficulty score, while number of years of clinical experience indirectly affected the score by influencing the Physician’s Belief Score. This constellation of variables explained 18% of the variance and was a well-fitted model (CMIN = 1.638, AGFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03 and Hoelter’s “critical N” = 704). The two variables with the greatest total influence on difficulty were symptom severity (total effect 0.27) and the Physician’s Belief Score (total effect 0.29). By convention, these individual variable effects would be considered small.22

Figure 1.

Structural equation model of difficulty with standardized estimates of effect

DISCUSSION

While the label of “difficult” is assigned by the clinician, it is clear that both the clinician and patient are troubled by the interaction. Patients in these encounters have less trust and satisfaction with the clinician they saw, and a greater number of unmet expectations, effects that persisted over the 2 weeks we followed patients. In addition, patient’s symptoms were more likely to worsen during these 2 weeks. A number of physician and patient characteristics correlated with clinician perception of an encounter “difficulty.” “Difficult” patients had a greater number of physical symptoms, worse functional status, higher utilization, greater symptom severity and were more likely to have underlying psychiatric disorders. Clinicians with worse psychosocial attitudes and less clinical experience experienced more encounters as difficult.

The SEM model provides a fuller and more subtle picture of the interaction of variables that influence difficulty. While our multivariable model in this paper is consistent with previous studies, suggesting an important direct role for depressive and anxiety disorders in being considered “difficult,” the SEM model found that the impact of mental disorders is indirect, mediating its effects on the number of patient symptoms and functional status. In addition, previous research has largely focused on patient characteristics associated with “difficulty,” but our SEM model suggests that the most important single predictor of a difficult encounter was the clinician’s score on the Physician’s Belief Scale.

The “difficult” patient that emerges from our SEM model has a high rate of health utilization, poor functioning, many symptoms and a large number of expectations. This description is likely to resonate with most primary care physicians as one they would consider “difficult.” In contrast to the “good” patient described by Lorber, this patient’s symptom may not have a simple biological explanation and may be less likely to improve.23

The association between Physician Belief Scale and difficulty may not be surprising. The instrument evaluates a clinician’s orientation toward dealing with the psychosocial aspects of medicine. Clinicians with better scores on the PBS have been found to have a more open, communicative style and have lower rates of liability claims. Moreover, physicians with more interest or skill in psychosocial communication may experience fewer encounters as difficult. This could also explain the relationship between difficulty and improved symptom outcomes. More experienced clinicians may have greater skill in dealing with “difficult” patients. There is literature suggesting that more skillful communication improves outcomes among somatizing patients, so the relationship between Physician Belief Score and better outcomes among “difficult” patients may not be surprising.24

Our study has several limitations. First, we explained only a small portion of the variance in difficulty. It is likely that we didn’t collect other elements that impact difficulty; in particular our measures on physician characteristics were limited. Other important, unmeasured and potentially mutable factors include physician burnout, empathy and mindfulness. Second, instead of directly observing physician behavior, we used a surrogate marker for physician orientation, the Physician Belief Scale. It would be better to directly observe clinician and patient behaviors and correlate these behaviors with encounter difficulty. Third, “difficult” patients tended to be those with multiple symptoms. In our patient population, we have found that such patients tend to have slower symptom resolution.23 The effect of “difficulty” on symptom resolution is at least partially a manifestation of somatization rather than the experience of the encounter itself. However, the distribution of somatizing patients was relatively uniform across clinicians. More experienced clinicians not only experienced fewer somatizing patients as “difficult,” they also had a better impact on symptom outcome. Other studies have shown improvement in symptom outcome among somatizing patients based on a clinician communication intervention.24 Fourth, the relationship between years of experience and Physician Belief Score may be confounded; more experienced clinicians may have chosen to work in the primary care setting in which the study was conducted and therefore may be more patient-centered and psychosocially sensitive/adept because of personal characteristics that are independent of years of experience. Fifth, though consistent with other studies, our findings are based on a single institution. Finally our follow-up was relatively short, only 2 weeks. Previous studies have demonstrated that 2-week symptom outcomes correlate well with 3-month outcomes.25

Our results are consistent with previous studies. Across different cultures and practice settings, about 15% of primary care encounters are experienced as “difficult.”1,2,5,8 Feelings of helplessness, frustration, stress, burnout and failure are common clinician responses to “difficult patient encounters.”5,7,17,25 Others have proposed clinician self awareness24,26,27 and patient-centered interview techniques24,28–31 as tools for difficult encounters. Data on how well these proposals work are sparse, though they have been found to improve patient satisfaction24 and enhance adherence.32 Studies to determine if such interventions decrease clinician discomfort with such encounters and whether other outcomes can be improved are needed.

CONCLUSION

About 15% of patient encounters are experienced as difficult; both patient and clinician characteristics contribute to difficulty. “Difficult” patients commonly have underlying mental disorders and have high utilization rates, high somatization and poor functional status. Patients emerging from these encounters are less satisfied, have lower trust, a greater number of unmet expectations and are more likely to have worsening of their presenting symptom. Less experienced and less psychosocially oriented doctors experience a higher proportion of encounters as “difficult.” A number of approaches to managing difficult encounters have been proposed, though most have not been rigorously tested. Research directly observing patient and provider behaviors during “difficult” encounters as well as identifying changeable physician behaviors that improve outcomes are needed.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed, in any way, to represent those of the US Army, the Department of Defense or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed, in any way, to represent those of the US Army, the Department of Defense or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Jackson JLKK. Difficult patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic: clinical predictors and outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1069–75. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.10.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn SR KK, Spitzer RL, Brody D, Williams J, Linzer M, deGruy FV. "The difficult patient": prevalence, psychopathology, and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Hahn SR, Wills TA, Stern V. Budner NS. The difficult doctor-patient relationship: somatization, personality and psychopathology. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(6):647–57. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson JL. KK. Prevalence, impact and prognosis of multisomatoform disoder in primary care: a 5-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):430–34. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.KW LEHB, Korff M, Bush T, Lipscomb P, Russo J, Wagner E. Frustrating patients: physician and patient perspectives among distressed high users of medical services. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:241–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02598969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker EA KW, Keegan D, Gardner G, Sullivan M. Predictors of physician frustration in the care of patients with rheumatologic complaints. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19:315–23. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(97)00042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krebs EE. GJ, Konrad TR. The difficult doctor? Characteristics of physicians who report frustration with patients: an analysis of survey data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(128):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinmetz DTH. The difficult patient as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract. 2001;18:495–500. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorber J. Good patients and problem patients: conformity and deviance in a general hospital. J Health Soc Behav. 1975;16:213–225. doi: 10.2307/2137163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson JE JT, Pinholt EM, Carpenter JL. Content of ambulatory internal medicine practice in an academic army medical center and army community hospital. Military Med. 1988;153:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson JL SJ, Cheng E, Meyer G. Patients diagnosis and procedures in a military internal medicine clinic; comparison with civilian. Military Med. 1999;164(3):194–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson JL OMP, Kroenke K. A psychometric comparison of military and civilian medical practices. Mil Med. 1999;164(2):112–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke KSR, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:258–66. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin HR GB, Rogers WH, Kosinki M, Mchoney CA, Ware JE. Patients ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings: results of the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1993;270:835–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashworth CD WP, Montano D. A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of care. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19(11):1235–8. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levinson W. RD, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. "Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosmer DW LS. Applied Logistic Regression. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1989.

- 18.Byrne B. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2001.

- 19.Browne MW CR. Alternative Ways for Assessing Model Fit in Testing Structural Equation Models. In: Bollen KA LJ, editor. Newbury Park Sage, 1993:136-62.

- 20.Hoelter J. The analysis of covariance structures: goodness of fit indices. Sociological Methods and Research. 1983;11:325–44. doi: 10.1177/0049124183011003003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carmines EG MJ. Analyzing Models with Unobserved Variables in Social Measurement. Beverly Hills: Sage, 1981.

- 22.AJ KLE, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27:S178–S89. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Prevalence, impact, and prognosis of multisomatoform disorder in primary care: a 5-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):430–4. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816aa0ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, Sirbu C, Hodges A, Collins C, Dwamena FC, Lein C, William Given C, Given B, Goddeeris J. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):671–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson JL. PM, Kroenke K. Outcome and impact of mental disorders in primary care at 5 years. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(3):270–6. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180314b59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drossman D. The problem patient: evaluation and care of medical patients with psychocosial disturbances. Annals Intern Med. 1978;88:366–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-3-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith RC OG, Hoppe RB, et al. Efficacy of a one-month training block in psychosocial medicine for residents: a controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:535. doi: 10.1007/BF02598223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart M. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ. 1995;152(9):1423–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith R. Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence Based Method. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2002.

- 30.Leiblum SR SE, Seehuus M, DeMaria A. To BATHE or not to BATHE: patient satisfaction with visits to their family physician. Fam Med. 2008;40(6):407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delbanco T. Enriching the doctor-patient relationship by inviting the patients perspective. Ann Intern Med. 1992:116-414. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Boyle D. DB, Platt F. Invite, Listen and Summarize: A Patient-Centered Communication Technique. Acad Med. 2005;80:29–32. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitzer RL WJ, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV, Hanh SR. Utility of a New Procedure for Diagnosing Mental Disorders in Primary Care. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA 1994;272:1749-56. [PubMed]

- 34.Ware JE NE, Shelbourne CD, Stewart AL. Preliminary tests of a 6-item general health survey: a patient application in measuring functioning and well being. In the Medical Outcomes Study Approach Durham Duke University Press 1992.

- 35.Groves J. Taking care of the hateful patient N. Engl J Med. 1978;80:1211–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197804202981605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]