ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is an important element of medical education. However, limited information is available on effective curricula.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate a longitudinal medical school EBM curriculum using validated instruments.

DESIGN, PARTICIPANTS, MEASUREMENTS

We evaluated EBM attitudes and knowledge of medical students as they progressed through an EBM curriculum. The first component of the curriculum was an EBM “short course” with didactic and small-group sessions occurring at the end of the second year. The second component integrated EBM assignments with third-year clinical rotations. The 15-point Berlin Questionnaire was administered before the course in 2006 and 2007, after the short course, and at the end of the third year. The 212-point Fresno Test was administered before the course in 2007 and 2008, after the short course, and at the end of the third year. Self-reported knowledge and attitudes were also assessed in all three classes of medical students.

RESULTS

EBM knowledge scores on the 15-point Berlin Questionnaire increased from baseline by 3.0 points (20.0%) at the end of the second year portion of the course (p < 001) and by 3.4 points (22.7%) at the end of the third year (p < 001). EBM knowledge scores on the 212-point Fresno Test increased from baseline by 39.7 points (18.7%) at the end of the second year portion of the course (p < 001) and by 54.6 points (25.8%) at the end of the third year (p < 001). On a 5-point scale, self-rated EBM knowledge increased from baseline by 1.0 and 1.4 points, respectively (both p < 001). EBM was felt to be of high importance for medical education and clinical practice at all time points, with increases noted after both components of the curriculum.

CONCLUSIONS

A longitudinal medical school EBM was associated with markedly increased EBM knowledge on two validated instruments. Both components of the curriculum were associated with gains in knowledge. The curriculum was also associated with increased perceptions of the importance of EBM for medical education and clinical practice.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1642-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: medical education, evidence-based medicine, medical school

BACKGROUND

Every accredited US medical school is required to offer coursework to “allow students to acquire skills of critical judgment based on evidence and experience”,1 skills at the heart of evidence-based medicine (EBM). In addition, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires as part of the Practice-Based Learning and Improvement competency that residents be able to “locate, appraise, and assimilate evidence from scientific studies related to their patients’ health problems”.2 Despite these training requirements, lack of knowledge and skills is identified as a key factor limiting EBM application among practicing physicians and residents.3 Although medical school courses could impart these required skills early in medical careers, limited data are available to guide development of effective EBM curricula.4 Historically, the majority of EBM courses have been seminar series, workshops, or “short courses”.5–8 Courses of EBM instruction integrated longitudinally with clinical practice are rare,9–11 despite limited but supportive evidence in favor of such teaching approaches to EBM.12

Objective assessment of EBM skills is essential, as self-reported skills correlate poorly with actual EBM knowledge.13,14 Despite this, EBM curricula have seldom been evaluated using validated instruments to assess both short-term acquisition and longer term retention of EBM knowledge.15 Furthermore, the available assessment tools for EBM knowledge each address differing domains of EBM.16 Although the Berlin Questionnaire17 and the Fresno Test of competence in evidence-based medicine18 are the only instruments with well-documented validity evidence to assess each of the four steps of evidence-based practice (ask, acquire, appraise, and apply),16 they focus on very different areas of knowledge because of different instrument designs. The Berlin Questionnaire evaluates primarily applied knowledge through its multiple-choice format, with limited assessment of specific skills such as developing a clinical question or a search strategy, while the Fresno Test requires written demonstration of knowledge and skills across the four steps of evidence-based practice applied to clinical scenarios in a mixed essay/short-answer format.

We previously reported results of a pilot study investigating the potential effectiveness of a new EBM curriculum at the Mayo Medical School in a single class of students using the Berlin Questionnaire.14 This curriculum combines a short course at the end of the second year of medical school with longitudinal EBM practice integrated throughout third year clinical experiences. We found that Berlin Questionnaire scores and self-reported EBM knowledge increased after the short course and increased further at the end of the integrated course. Attitudes regarding the importance of EBM for medical education and clinical practice were positive throughout the curriculum, peaking after the short course. To better define the effectiveness of this curriculum in teaching the full range of EBM skills, we extended this pilot study by assessing Berlin Questionnaire results in a second class of students, in addition to following two classes of students using the Fresno Test.

METHODS

Participants

Second-year medical students at the Mayo Medical School enrolled in the required EBM course in 2006, 2007, and 2008 participated in this study. Students were eligible if they were scheduled to begin third-year clerkships immediately following the second year of medical school.

Curriculum

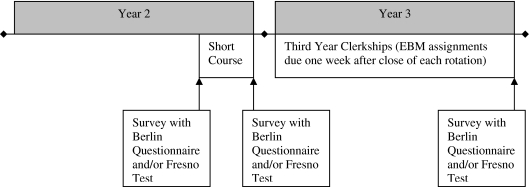

The current EBM curriculum at the Mayo Medical School is detailed in the online Appendix, and the original curriculum has been described previously.14 An illustrative timeline for the curriculum is presented in Fig. 1. This curriculum began in 2006 with a short course near the end of the second year of medical school consisting of 22 contact hours and adapted from the model developed at McMaster University, Canada.19 Didactic sessions are used to introduce EBM skills following the Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature text for common article types in the medical literature (therapy, harm, diagnosis, prognosis, and systematic reviews).12 Students then engage with the course instructors (CPW, TMJ, and FSM) in small group sessions during which journal articles are critically appraised following the criteria introduced in the didactic sessions.

Figure 1.

Schematic of course timeline, illustrating course elements and timing of surveys, Berlin Questionnaires, and Fresno Tests.

The curriculum continues throughout the third year of medical school, integrated with clinical experiences. During each third-year clinical rotation (originally Internal Medicine, Surgery, Pediatrics, Obstetrics-Gynecology, Neurology, Psychiatry, and Family Medicine), students generate a clinical question based on a patient interaction, search for an article addressing that question, critically appraise the article, and produce a written two-page summary of the evidence-based practice steps and how the evidence applied to the patient regarding whom the clinical question arose. It is suggested to students that each assignment not take more than 4 to 6 h of their effort. The course instructors evaluate each assignment and electronically provide substantive feedback on each student’s review. The course is graded on a pass-fail scale based on student feedback suggesting this allowed greater attention to content by removing the distraction of trying to achieve an Honors grade.

In 2007 and 2008, the course remained largely unchanged from its 2006 inception. However, due to structural changes to the Family Medicine clerkship, EBM assignments were no longer required for Family Medicine after 2006. In addition, the course contact hours decreased from 22 to 20 with increased efficiency in delivering the course content, particularly the background epidemiology content, which was further integrated into discussions of the Therapy and Diagnosis article types. No topics were removed from the curriculum, however.

Instructors are provided with 1 h of supported time for each graded assignment, in addition to administrative time for direct student contact during the short course and course maintenance. The instructors each have advanced training in biostatistics and epidemiology, and had participated in How to Teach Evidence-Based Clinical Practice workshops at McMaster University. In addition, two instructors (CPW and FSM) had previously taught basic and advanced EBM topics to internal medicine residents at Mayo Clinic.

Evaluation Instruments

Each student completed testing on the first day of the course, at the completion of the second-year short course, and upon completion of the third year of medical school. Students in all three years reported their self-rated EBM knowledge and their assessment of the importance of EBM for medical education and clinical practice on 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (“very low”) to 5 (“very high”). Students in the 2006 and 2007 short courses completed the Berlin Questionnaire, a well-validated, reliable, and objective instrument designed to measure EBM knowledge.17 This instrument consists of 15 multiple-choice questions designed to assess the ability to apply concepts rather than simply reproduce facts. It covers a wide range of EBM domains, including interpretation of evidence, relating a clinical problem to a clinical question, study designs for specific clinical questions, and quantitative aspects of research. The questions are structured around clinical scenarios and linked to published research literature. Scores on this instrument may range from 0 to 15, and each question receives equal weight. In the development of this instrument, medical students with no prior EBM experience had mean scores of 4.2 (28%), and EBM course participants with limited EBM experience had pre-course mean scores of 6.3 (42%). Experts with formal EBM training had mean scores of 11.9 (79%).17

Students in the 2007 and 2008 short courses completed the Fresno Test,18 which is the only other instrument assessing each of the four steps of evidence-based practice, and also has sound validity evidence supporting its use for measurement of EBM knowledge.16 This instrument is built around a clinical scenario, with questions requiring students to demonstrate core EBM skills including developing a focused clinical question, demonstrating how to search for literature answering the question, and appraising the validity, results, and applicability of a study. The Fresno Test also includes a section on standard EBM calculations, including 2 × 2 table values for diagnostic test performance. Scores on this instrument may range from 0 to 212. In the development of this instrument, family practice residents and faculty with no prior formal EBM instruction had mean scores of 95.6 (45%), while self-identified EBM experts had mean scores of 147.5 (70%).18 Both of the two psychometrically equivalent formats for the Berlin Questionnaire and Fresno Test were used, with each student assigned to an initial format via computer-generated randomization on the first day of the course. Students then received the alternate format at the second administration, and the initial format again at the third administration.

The Berlin Questionnaire was administered alone initially because of instructor concerns about grading workload. Once the curriculum was largely established, sufficient time was available for grading of the Fresno Test. To allow 2 years of outcome data for each instrument, the Berlin Questionnaire was administered in 2006 and 2007, and the Fresno Test was administered in 2007 and 2008, as described. Completion of the instruments was not mandatory, and scores were not part of students’ grades in the course. No incentives were offered to students beyond informing them that test results would help the instructors understand the benefits and weaknesses of the designed curriculum.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Differences in EBM attitudes and knowledge between each of the three time points were tested using Wilcoxon signed rank tests for paired data. All available cases were used for each pairwise comparison, and complete-case analysis was performed to ensure consistency of results. Nonparametric statistics were applied given the ordinal nature of the data. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05. The Mayo Clinic institutional review board approved this study.

RESULTS

Of 99 eligible students from 2006–2008, at least 93 (94%) responded to the self-reported knowledge and importance of EBM questions at each time point (Table 1). Of 67 eligible students from 2006 and 2007, at least 64 (96%) completed Berlin Questionnaires at each time point. Of 67 eligible students from 2007 and 2008, at least 64 (96%) completed Fresno Tests at each time point. The eligible sample consisted of 45 male students (45%) and 54 female students (55%), with an average age at the start of the course of 25.3 years.

Table 1.

Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) Knowledge and Attitude Mean Scores Over the Course of the Medical School EBM Curriculum

| Variable (possible range) | Eligible n | Baseline (n) | End year 2 (n) | p* | End year 3 (n) | p* | p† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin score (0–15)‡ | 67 | 6.3 (64) | 9.3 (65) | <0.001 | 9.7 (66) | <0.001 | 0.21 |

| Fresno score (0–212)§ | 67 | 97.8 (65) | 137.5 (66) | <0.001 | 152.4 (64) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Self-rated EBM knowledge (1–5) | 99 | 2.1 (93) | 3.1 (97) | <0.001 | 3.5 (99) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Importance for medical education (1–5) | 99 | 3.7 (94) | 4.2 (97) | <0.001 | 4.1 (99) | <0.001 | 0.45 |

| Importance for clinical practice (1–5) | 99 | 4.0 (94) | 4.5 (97) | <0.001 | 4.5 (99) | <0.001 | 0.88 |

*Comparison with baseline, Wilcoxon signed rank test

†Comparison with result at the end of year 2, Wilcoxon signed rank test

‡Median Berlin scores (interquartile range) were 6.0 (5–8) at baseline, 9.0 (8–11) at the end of year 2, and 10.0 (8–11) at the end of year 3

§Median Fresno scores (interquartile range) were 94.0 (87–111) at baseline, 142.5 (118–159) at the end of year 2, and 152.5 (139–166) at the end of year 3

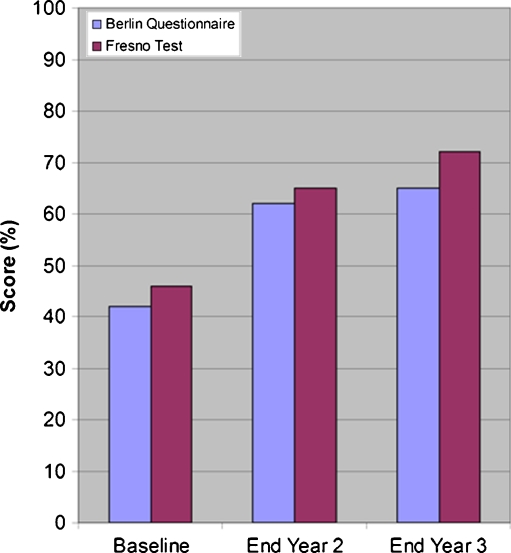

Prior to the course, self-rated EBM knowledge was low (average score 2.1 out of 5 possible), and increased upon completion of the short course (average score 3.1, p < 001). Self-rated EBM knowledge further increased after the longitudinal curriculum (average score 3.5, p < 001 compared to the end of the short course). The average Berlin Questionnaire score increased from 6.3 (42%) to 9.3 (62%, p < 001) by the end of the second-year portion of the curriculum, and to 9.7 (65%, p = 21 compared to the end of the short course) by the end of the third year (Fig. 2). Median Berlin Questionnaire scores (interquartile range) were 6.0 (5–8), 9.0 (8–11), and 10.0 (8–11), respectively.

Figure 2.

Berlin Questionnaire and Fresno Test evidence-based medicine (EBM) knowledge scores, reported as percent of total possible score, over the course of the medical school EBM curriculum.

The average Fresno Test score increased from 97.8 (46%) to 137.5 (65%, p < 001) by the end of the second-year portion of the curriculum and further increased to 152.4 (72%, p < 001 compared to the end of the short course) by the end of the third year (Fig. 2). Median Fresno Test scores (interquartile range) were 94.0 (87–111), 142.5 (118–159), and 152.5 (139–166), respectively.

The perceived importance of EBM for both medical education and clinical practice was moderately high prior to the course (average score 3.7 and 4.0, respectively, out of 5 possible). These values increased over the short course component of the curriculum to 4.2 and 4.5, respectively (both p < 001), and remained stable through the third-year portion of the curriculum.

DISCUSSION

This study lends further support for the effectiveness of this medical school EBM curriculum in improving EBM knowledge, skills, and attitudes by showing these improvements across multiple years of students and as measured by the only two current EBM knowledge instruments evaluating the full spectrum of necessary EBM skills. The observed increases in EBM knowledge resulted in scores at the conclusion of the curriculum approaching (for the Berlin Questionnaire) or exceeding (for the Fresno Test) those of EBM experts tested in the development of each instrument.

Improvement in EBM knowledge occurred during both phases of the curriculum in this group of Mayo Clinic medical students. Key principles of EBM are introduced during the initial short course, which includes education in basic epidemiology and guided appraisal of several common article types. The short course establishes a foundation of EBM knowledge by addressing the full range of EBM skills, teaching students how to ask clinical questions, search for the best evidence to answer these questions, appraise the evidence, and apply it to clinical practice. The curriculum then adheres to the literature-based recommendation that EBM courses be integrated with clinical learning9–12,20 by incorporating EBM instruction longitudinally into clerkship rotations. Students apply their developing EBM skills to patient care issues encountered in clinic and on the wards in this component of the curriculum, during which assignments are evaluated and feedback provided by EBM experts. One benefit of this approach integrating EBM with actual patient care during the core clerkships is effective modeling of the use of EBM for application in practice situations occurring outside of training environments and later in students’ careers.12

It is also notable that the improvements seen across the duration of this curriculum were far larger than those seen in prior integrated curricula evaluated using the Fresno Test.21,22 For example, Aronoff et al.22 reported a 9% increase in Fresno Test scores in their study of an integrated EBM curriculum, compared to the 26% increase seen in this study. The reasons for this difference are not entirely clear, but may relate to the more extensive pre-clerkship experience or involvement of highly experienced EBM experts in the Mayo Clinic curriculum. Also, Aronoff et al. applied online didactic teaching, and it is possible that their smaller curricular effects suggest limits to the effectiveness of such web-based curricula.23 Further exploration of the reasons for differences in the effectiveness of EBM curricula is needed.

Our study has limitations. First, given the small size of each Mayo Medical School class, there was no concurrent control group, although students served as their own controls in the pre-post design. Therefore, it is possible that education occurring outside of the formal EBM curriculum could account for the observed increases in EBM knowledge. However, there is no other specific EBM teaching in the Mayo Medical School curriculum, and in fact during the time frame of this study there was no additional formal exposure to epidemiology or biostatistics in the curriculum. Second, the instructors for this curriculum have advanced EBM skills and training, which may not be readily available in some environments. It is not clear that the curriculum as developed would remain effective if administered by non-experts. Third, although the Berlin and Fresno tests provide broad assessments of EBM knowledge, they are not exhaustive. There may be specific EBM-related skills less well addressed by these instruments for which the effectiveness of this curriculum remains unclear. Finally, our study does not allow insight into differences in future practice patterns or care quality as a result of the EBM curriculum. For these reasons, we encourage further evaluation of our curriculum at other institutions and in other learning settings, particularly larger medical schools that might feasibly incorporate independent control groups.

In summary, this study advances the evidence that a medical school EBM curriculum combining an initial short course and subsequent integration of EBM practice with clinical activities results in sustained increases in perceived and measured EBM knowledge. Further study is needed to determine whether this medical school curriculum has sustained benefits beyond medical school into postgraduate medical education and practice. However, this curriculum effectively satisfies medical school accreditation requirements and prepares students to meet the additional competency requirements of residency training and independent medical practice.

ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 56 kb)

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

Research Sponsors None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and structure of a medical school: standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. Available at: http://www.lcme.org/functions2010jun.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2010

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements: general competencies. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/outcome/comp/GeneralCompetenciesStandards21307.pdf. Accessed August 18. 2010.

- 3.Dijk N, Hooft L. Wieringa-de Waard M. What are the barriers to residents’ practicing evidence-based medicine? A systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85:1163–1170. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d4152f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hatala R, Guyatt G. Evaluating the teaching of evidence-based medicine. JAMA. 2002;288:1110–1112. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman GR, Shannon SI. Effectiveness of instruction in critical appraisal (evidence-based medicine) skills: a critical appraisal. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;158:177–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green ML. Graduate medical education training in clinical epidemiology, critical appraisal, and evidence-based medicine: a critical review of curricula. Acad Med. 1999;74:686–694. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199906000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor R, Reeves B, Ewings P, Binns S, Keast J, Mears R. A systematic review of the effectiveness of critical appraisal skills training for clinicians. Med Educ. 2000;34:120–125. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akl EA, Izuchukwu IS, El-Dika S, Fritsche L, Kunz R, Schunemann HJ. Integrating an evidence-based medicine rotation into an internal medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2004;79:897–904. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200409000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnett SH, Kaiser S, Morgan LK, et al. An integrated program for evidence-based medicine in medical school. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mar C, Glasziou P, Meyer D. Teaching evidence based medicine. BMJ. 2004;329:989–990. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in evidence based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329:1017–1021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan KS, Coomarasamy A. A hierarchy of effective teaching and learning to acquire competence in evidence-based medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan KS, Awonuga AO, Dwarakanath LS, Taylor R. Assessments in evidence-based medicine workshops: loose connection between perception of knowledge and its objective assessment. Med Teach. 2001;23:92–94. doi: 10.1080/01421590150214654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.West CP, McDonald FS. Evaluation of a longitudinal medical school evidence-based medicine curriculum: a pilot study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1057–1059. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0625-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CA, Ganschow PS, Reilly BM, et al. Teaching residents evidence-based medicine skills: a controlled trial of effectiveness and assessment of durability. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:710–715. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.91026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaneyfelt T, Baum KD, Bell D, Feldstein D, Houston TK, Kaatz S, et al. Instruments for evaluating education in evidence-based practice: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1116–1127. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritsche L, Greenhalgh T, Falck-Ytter Y, Neumayer H-H, Kunz R. Do short courses in evidence based medicine improve knowledge and skills? Validation of Berlin questionnaire and before and after study of courses in evidence based medicine. BMJ. 2002;325:1338–1341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7376.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos KD, Schafer S, Tracz SM. Validation of the Fresno Test of competence in evidence based medicine. BMJ. 2003;326:319–321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7384.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt G, Rennie D, editors. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature. AMA Press: Chicago; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradt P, Moyer V. How to teach evidence-based medicine. Clin Perinatol. 2003;30:419–433. doi: 10.1016/S0095-5108(03)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Willett LR, Murphy DJ, O’Rourke K, Sharma R, Shea JA. Impact of an evidence-based medicine curriculum on resident use of electronic resources: a randomized controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1804–1808. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0766-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aronoff SC, Evans B, Fleece D, Lyons P, Kaplan L, Rojas R. Integrating evidence based medicine into undergraduate medical education: combining online instruction with clinical clerkships. Teach Learn Med. 2010;22:219–223. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2010.488460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Internet-based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:1181–1196. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(DOC 56 kb)