Abstract

The anaphase promoting complex (APC) is a ubiquitin ligase that promotes the degradation of cell-cycle regulators by the 26S proteasome. Cdc20 and Cdh1 are WD40-containing APC co-activators that bind destruction boxes (DB) and KEN boxes within substrates to recruit them to the APC for ubiquitination. Acm1 is an APCCdh1 inhibitor that utilizes a DB and a KEN box to bind Cdh1 and prevent substrate binding, although Acm1 itself is not a substrate. We investigated what differentiates an APC substrate from an inhibitor. We identified the Acm1 A-motif that interacts with Cdh1 and together with the DB and KEN box is required for APCCdh1 inhibition. A genetic screen identified Cdh1 WD40 domain residues important for Acm1 A-motif interaction and inhibition that appears to reside near Cdh1 residues important for DB recognition. Specific lysine insertion mutations within Acm1 promoted its ubiquitination by APCCdh1 whereas lysine removal from the APC substrate Hsl1 converted it into a potent APCCdh1 inhibitor. These findings suggest that tight Cdh1 binding combined with the inaccessibility of ubiquitinatable lysines contributes to pseudosubstrate inhibition of APCCdh1.

Keywords: Cdh1, cell cycle, destruction box, ubiquitination

Introduction

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway plays a central role in cell-cycle progression by promoting the degradation of key cell-cycle regulators. Ubiquitin is transferred in an enzymatic cascade from a ubiquitin activating enzyme (E1) to a ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (E2) and then to the substrate, typically with the help of a ubiquitin ligase (E3), culminating in the degradation of the target protein by the 26S proteasome (Hochstrasser, 1996; Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998; Petroski, 2008). The Skp1–cullin–F-box (SCF) complex and the anaphase promoting complex (APC) are the major RING domain-containing E3s involved in cell-cycle control. These E3 complexes behave as scaffolds to facilitate the covalent transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to lysine residues within the substrate (Cardozo and Pagano, 2004; Peters, 2006; Thornton and Toczyski, 2006). Two central cell-cycle events regulated by the APC are sister chromatid separation and the inactivation of cyclin-dependent protein kinases (Cdks) through ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of securin and mitotic cyclins, respectively (Peters, 2006; Thornton and Toczyski, 2006).

In addition to its core subunits, APC function during mitotic cell cycles requires the binding of a WD40-containing protein, either Cdc20 or Cdh1. These proteins bind directly to APC substrates through their carboxyl-terminal WD40 domains and to the APC through both a ‘C-box’ and a carboxyl-terminal ‘IR’ tail motif (Peters, 2006; Thornton and Toczyski, 2006; Yu, 2007). Cdc20 and Cdh1 also stimulate the ligase activity of the APC core subunits independent of their role in substrate recruitment (Kimata et al, 2008a). The WD40 domains of Cdc20 and Cdh1 recognize conserved degradation motifs in APC substrates with the best characterized being the destruction box (DB; RxxLxxxxN/D/E) (Glotzer et al, 1991) and the KEN box motifs (Pfleger and Kirschner, 2000; Burton et al, 2005; Kraft et al, 2005; Kimata et al, 2008b). Four amino acids located in the first and seventh WD40 repeats of Cdc20 and Cdh1 participate directly in DB recognition and are required for efficient APC-mediated ubiquitination of substrates in vitro (Kraft et al, 2005).

APC activity is controlled at multiple levels, including regulation of the binding of Cdc20 and Cdh1 to the APC. Cdc20 protein levels are cell cycle regulated and, in addition, it only binds to phosphorylated APC, with the peak association occurring during mitosis (Peters, 2006; Thornton and Toczyski, 2006; Yu, 2007). In contrast, Cdh1 binding to the APC is inhibited by phosphorylation of Cdh1 by Cdks (Cdc28 in budding yeast), thereby limiting APCCdh1 activity primarily to G1 when Cdk activity is low (Zachariae et al, 1998; Sorensen et al, 2001).

APC activity is also regulated by the binding of pseudosubstrate inhibitors to Cdc20 or Cdh1 to prevent their association with substrates. Cdc20 is inhibited by the binding of a Mad2–BubR1 (Mad3 in budding yeast)–Bub3 complex during the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which prevents the degradation of the anaphase inhibitor securin until all chromosomes are properly attached to the mitotic spindle (Yu, 2007). Evolutionarily conserved KEN boxes within Mad3/BubR1 are required for the SAC and function to bind Cdc20 and thereby inhibit substrate binding (Burton and Solomon, 2007; King et al, 2007; Malureanu et al, 2009). Emi1 and Emi2/Erp1 in higher eukaryotes inhibit APCCdh1 during somatic and meiotic cell cycles, respectively (Reimann et al, 2001; Hsu et al, 2002; Reimann and Jackson, 2002; Schmidt et al, 2005). In addition to a DB, Emi1 also requires a Zinc-binding region (ZBR) for inhibition of Cdh1 and mutation of the ZBR converts Emi1 from an inhibitor into an APC substrate (Miller et al, 2006). In fission yeast, Mes1 is both an APCCdc20 inhibitor and substrate during meiosis (Kimata et al, 2008b). Mes1 requires a DB and a KEN box for both of these activities; its inhibitory properties have been attributed to its much higher affinity for Cdc20 than other APC substrates (Izawa et al, 2005; Kimata et al, 2008b).

Budding yeast Acm1 inhibits APCCdh1 by binding to Cdh1 via a DB (‘DB3’) and a KEN box, thereby blocking substrate binding (Martinez et al, 2006; Dial et al, 2007; Choi et al, 2008; Enquist-Newman et al, 2008; Hall et al, 2008; Ostapenko et al, 2008). Although Acm1 is ubiquitinated by APCCdc20 during mitosis (via recognition of ‘DB1’ near its N-terminus) (Enquist-Newman et al, 2008) and is unstable in G1-arrested cells, it is not an APCCdh1 substrate (Hall et al, 2008; Ostapenko et al, 2008). Acm1 is stabilized by Cdc28 phosphorylation. Thus, phosphorylation by Cdc28 simultaneously prevents Cdh1 from associating with the APC and stabilizes Acm1 to prevent non-productive Cdh1-substrate interactions (Hall et al, 2008; Ostapenko et al, 2008).

We have explored what features distinguish an APCCdh1 substrate from a pseudosubstrate inhibitor. By further investigating the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction we uncovered additional residues within Acm1 that are involved in Cdh1 binding and inhibition. A genetic screen identified WD40 residues within Cdh1 that are important for Acm1 recognition and that are predicted to lie in close proximity to amino acids known to participate in DB recognition. Furthermore, we demonstrate the importance of well-positioned ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues in determining whether the Cdh1-bound protein functions as a substrate or an inhibitor.

Results

The A-motif of Acm1 contributes to Cdh1 binding and Acm1 function

Acm1 utilizes DB3 and a KEN box to bind Cdh1 and block substrate interaction (Hall et al, 2008; Ostapenko et al, 2008). However, these motifs do not fully account for the ability of Acm1 to bind Cdh1. Thus, unlike the APCCdh1 substrate Hsl1, Acm1 containing mutations in DB3 and the KEN box could still bind Cdh1 with high affinity in vitro even in the presence of DB- and KEN box-containing peptides (Ostapenko et al, 2008). Further analysis revealed that a fragment of Acm1 containing amino-acid residues 58–128 could still bind efficiently to Cdh1-containing beads in vitro in a DB- and KEN box-independent manner, suggesting that an additional Cdh1 interaction motif resided within this fragment (Supplementary Figure S1). We identified this motif (see below) by subjecting amino acids 58–128 to alanine-scanning mutagenesis and testing the resulting Acm1 mutants for their ability to bind Cdh1 using the yeast two-hybrid system. The Cdh1 ‘bait’ protein in this assay lacked the N-terminal 200 amino acids and consisted of the WD40 domain of Cdh1 fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Cdh1-Δ200). We chose this construct because the Cdh1 WD40 domain can bind to both APC substrates (Burton et al, 2005; Kraft et al, 2005; Kimata et al, 2008b) and Acm1 (Choi et al, 2008) and because we found that full-length Cdh1 self-activated in the two-hybrid system independent of a ‘prey’ Gal4-activation domain fusion protein (data not shown). The Cdh1-Δ200 Gal4 DNA-binding fusion protein interacted with Hsl1 and Acm1 but not with a control Gal4-activation domain fusion protein (Supplementary Figure S2). Furthermore, mutation of the Hsl1 DB and KEN box eliminated the Cdh1-Δ200 interaction with Hsl1 whereas Cdh1-Δ200 could still interact with Acm1-N128 lacking DB3 and the KEN box, consistent with the postulated additional binding motif.

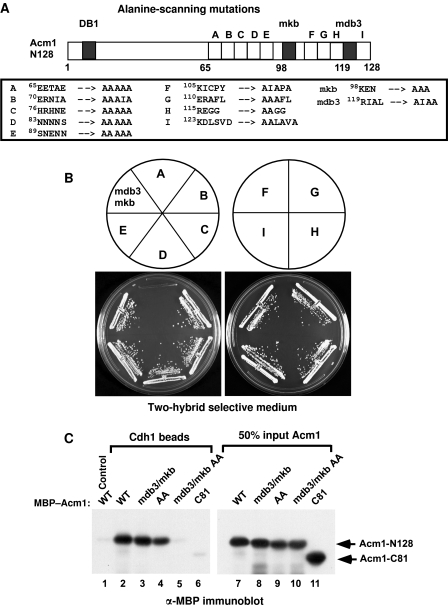

We used the Gal4-activation domain (‘prey’) plasmid encoding Acm1-N128 with mutations in DB3 and the KEN box as the template for the alanine-scanning mutagenesis. Clusters of 4–6 charged and polar residues within amino acids 58–128 were systematically mutated to alanines to produce mutants A through I (Figure 1A). Each Acm1-N128 mutant was expressed in the Cdh1-Δ200 yeast two-hybrid strain and tested for interaction by analysing growth on two-hybrid selective medium. Only mutation A (residues 65–69) disrupted the interaction of Acm1-N128-mdb3mkb with Cdh1-Δ200 (Figure 1B), consistent with a previous deletion analysis suggesting that a Cdh1-binding motif resided between amino acids 60 and 70 of Acm1 (Enquist-Newman et al, 2008). We denote this region the ‘A-motif.’ We narrowed down the critical residues for this interaction to E65 and E66 (see below). Mutations of E69 and E70 had no effect on the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction (data not shown). We tested the role of the A-motif of Acm1-N128 in binding full-length recombinant Cdh1 in vitro. Acm1-N128-mdb3mkb and Acm1-N128–AA (E65A E66A) could still interact with Cdh1 whereas combining these mutations eliminated binding (Figure 1C, lanes 2–5). Similarly, in the two-hybrid assay, mutations of DB3, the KEN box and the A-motif were all required to disrupt the Acm1-N128–Cdh1 interaction (Figure 2B). DB1 did not appear to contribute to Cdh1 binding. These results demonstrated that full-length Cdh1 used in the in vitro assay, and Cdh1-Δ200, from the two-hybrid assay, interacted similarly with Acm1-N128.

Figure 1.

The ‘A-motif’ in Acm1-N128 is important for Cdh1 binding. (A) Schematic of the alanine-scanning mutagenesis performed between amino acids 65 and 128 of Acm1-N128. The KEN box and DB3 were mutated to alanines (mkb and mdb3) in all alanine-scanning mutants. The amino-acid changes for each of the mutants are shown. (B) Two-hybrid interactions between Cdh1-Δ200 and Acm1-N128 alanine-scanning mutants A–I. Mutant A combined with mdb3 and mkb disrupted the Cdh1–Acm1 two-hybrid interaction. No other alanine-scanning mutant had any effect on the interaction. (C) The A-motif, KEN box and DB3 each contributes to Cdh1 binding in vitro. Control or full-length 6xHis–Cdh1-containing beads were incubated with the indicated MBP–Acm1-N128 proteins or with MBP–Acm1-C81. Acm1 binding was detected by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibodies. Acm1-C81 and Acm1-N128 with the AA (E65A, E66A), mdb3 and mkb mutations resulted in undetectable Cdh1 binding. Fifty percent of the input to each binding reaction is shown (right panel).

Figure 2.

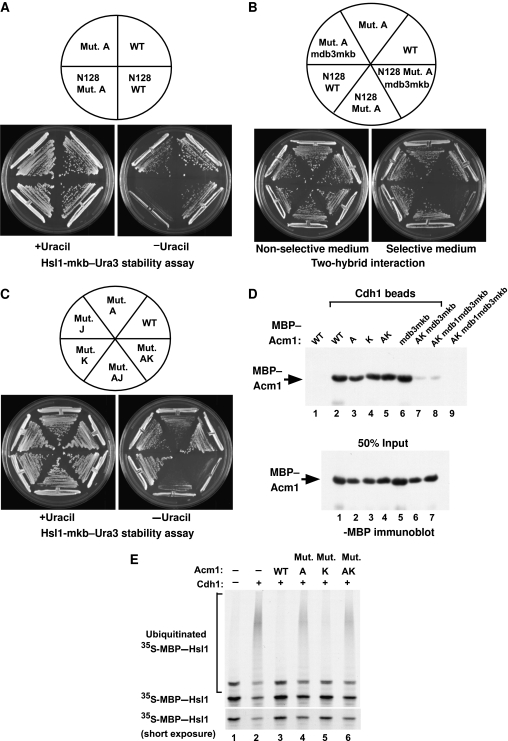

A carboxyl-terminal motif within full-length Acm1 collaborates with the A-motif in Cdh1 binding and inhibition. (A) The A-motif is important for inhibition of APCCdh1 function by Acm1-N128 in vivo. Cells expressed an Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 fusion protein, which allows cell growth in the absence of uracil only when APCCdh1 activity is low. Cells also expressed WT or Mut. A versions of full-length Acm1 (top half) or of Acm1-N128 (bottom half). Cells were grown in the presence (left) or absence (right) of uracil. (B) Yeast two-hybrid analysis of Cdh1 interaction with full-length (top half) and N128 (bottom half) forms of Acm1. Mutation of the A-motif together with mutations in the KEN box and DB3 disrupted the interaction of Acm1-N128, but not of full-length Acm1, with Cdh1-Δ200. (C) Mutant K, and to a lesser extent mutant J, collaborates with mutant A to disrupt APCCdh1 inhibition. Cells expressed full-length WT Acm1, or Acm1 containing alanine-scanning mutant A, mutant J (186SRSTDD → 186AAAAAA), mutant K (196KVVRK → 196AVVAA), or the AJ or AK double mutants in the Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 reporter strain used in (A). Cells were grown in the presence or absence of uracil. (D) The A-motif, the K-motif, DB3 and the KEN box all participate in the binding of full-length Acm1 to Cdh1. Top panel, control (lanes 1 and 9) or 6xHis–Cdh1-containing beads (lanes 2–8) were incubated with the indicated MBP–Acm1 full-length fusion proteins and bound proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibodies. Bottom panel shows 50% of the input used in each binding assay. (E) The A-motif is required for APCCdh1 inhibition in a ubiquitination assay in vitro. Cdh1 and the APC were pre-incubated with 1.0 μg of the indicated full-length Acm1 proteins before the addition of the APC substrate 35S-MBP–Hsl1. Unmodified and modified species were visualized by fluorography. Lower panel, a short exposure of the unmodified substrate.

We examined if the A-motif of Acm1 contributes to Cdh1 inhibition in vivo using a strain expressing an Hsl1–Ura3 fusion protein as the only source of Ura3 in the cell. The Hsl1 portion of the fusion protein contained a mutated KEN box to partially stabilize the fusion protein. This strain cannot grow in the absence of added uracil due to degradation of the Hsl1–Ura3 fusion protein via APCCdh1. However, deletion of CDH1 stabilizes the fusion protein and allows cell growth in the absence of added uracil (Burton et al, 2005) (data not shown). Overexpression of full-length Acm1, and to a lesser extent of Acm1-N128, inhibited APCCdh1 activity in this assay, allowing cell growth on plates lacking uracil (Figure 2A). Acm1-N128 with a mutated A-motif no longer inhibited Cdh1 as evidenced by the lack of growth in the absence of uracil, even though this form of Acm1 had an intact DB3 and KEN box and could bind to Cdh1 in vitro or in the two-hybrid assay (Figures 1C and 2B). Thus, the A-motif is important for Acm1 inhibition of APCCdh1 in an in vivo assay.

The carboxyl-terminus of Acm1 contributes to Cdh1 binding and inhibition

In the above experiment, we were surprised that full-length Acm1 with a mutated A-motif could still inhibit Cdh1 enough to allow cell growth in the absence of uracil, although it was not as effective as WT Acm1 (Figure 2A). This observation suggested that an additional motif within the last 81 amino acids of Acm1 also influences APCCdh1 activity. Despite having undetectable binding to Cdh1 on its own (Figure 1C), the carboxyl-terminal portion of Acm1 may nonetheless influence the binding of full-length Acm1 to Cdh1. Consistent with this suggestion, full-length Acm1 containing mutations in the A-motif, DB3 and the KEN box could still interact with Cdh1 in the two-hybrid assay and in the Cdh1 binding assay in vitro, whereas these mutations disrupted the interactions of Acm1-N128 with Cdh1 (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure S3). Together, these findings suggested that both the A-motif and an unidentified carboxyl-terminal motif of Acm1 contributed to Cdh1 binding and APCCdh1 inhibition.

Alignment of putative Acm1 orthologues from closely related yeast species using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Genomic Database Fungal Alignment viewer revealed two well-conserved regions located near the carboxyl-termini of the proteins, suggesting these might have a role in Acm1 function (Supplementary Figure S4). We designated these sequences motifs J (186SRSTDD191) and K (196KVVRK200). We mutated all six J-motif residues to alanine and the charged residues in the K-motif to alanine (AVVAA). Mutations in the A-, J- or K-motifs within full-length Acm1 still inhibited APCCdh1 in the Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 stability assay (Figure 2C). However, combining the A and K mutations (AK) and to a lesser extent the A and J mutations (AJ) substantially reduced growth on medium lacking uracil, indicating that these Acm1 mutants were compromised in their ability to inhibit Cdh1. Thus, these motifs appear to collaborate in APCCdh1 inhibition in this assay. In full-length Acm1, mutations of the A- and K-motifs together with DB3 and the KEN box were all required to disrupt Acm1–Cdh1 binding in vitro (Figure 2D, lane 7), consistent with the K-motif participating in the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction.

We next tested the importance of the Acm1 A- and K-motifs in inhibiting APCCdh1 activity in vitro. WT Acm1 inhibited the ubiquitination of Hsl1 in vitro whereas mutating the A-motif strongly reduced the inhibitory activity of Acm1 (Figure 2E). A similar loss of Acm1 inhibitory activity was previously found upon mutation of DB3 and the KEN box (Ostapenko et al, 2008). In contrast, mutation of the K-motif had only a minimal effect on APC inhibition (Figure 2E). It is currently unclear why the K-motif seems to have a larger role in vivo than in vitro. Together, these results suggest that all four Acm1 motifs that participate in Cdh1 binding have a functional role in the inhibition of APCCdh1 activity.

Identification of Cdh1 WD40 domain residues important for the A-motif interaction

To better understand how Acm1 inhibits Cdh1, we sought to identify the amino acids within the Cdh1 WD40 domain that interact with Acm1's A-motif and DB/KEN box motifs. Based on a model of the Cdh1 WD40 domain, a previous study identified residues in human Cdh1 responsible for recognizing a DB. Combining mutations they termed D1 (L179V P182A) and D2 (G463A D464A) to form the quadruple mutant D12 eliminated DB binding and Cdh1-mediated substrate ubiquitination in vitro (Kraft et al, 2005). We introduced the corresponding mutations (D1: L255V and P258A and D2: G535A and D536A) into the yeast Cdh1-Δ200 two-hybrid construct to test whether these residues had a role in APC substrate recognition in vivo. Strikingly, although Cdh1-Δ200–D12 failed to interact with Hsl1, it still interacted with Acm1 in the two-hybrid assay (Figure 3A). Moreover, Cdh1-Δ200–D12 failed to interact with Acm1–Mut. A, indicating that distinct residues within the WD40 domain participate in DB/KEN box and A-motif recognition and supporting the previous observation that DB and KEN box peptides disrupted Hsl1 but not Acm1 binding to Cdh1-containing beads in vitro (Ostapenko et al, 2008).

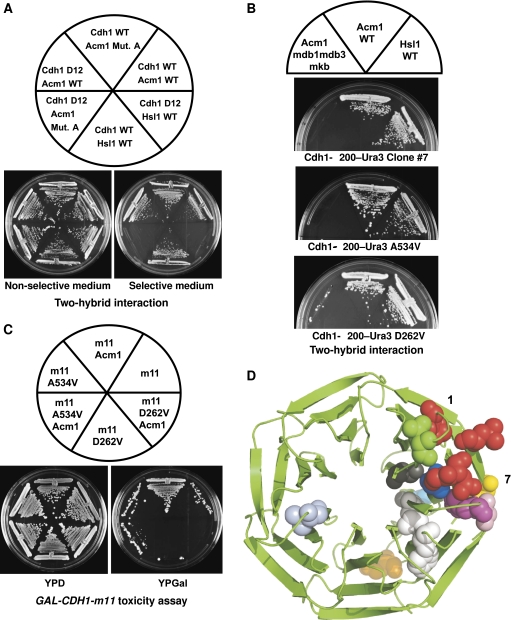

Figure 3.

Isolation of Cdh1 mutants that no longer recognize the A-motif of Acm1. (A) Two-hybrid analysis of the interaction of WT or D12 forms of Cdh1-Δ200 with Hsl1, WT Acm1 or Acm1-Mut. A. The Cdh1-Δ200 D12 mutant disrupted interaction with Hsl1 and Acm1-Mut. A but not with WT Acm1. (B) Two-hybrid analysis of the interaction of Cdh1-Δ200 WD40 mutants with Acm1-mdb1mdb3mkb, WT Acm1 and WT Hsl1. The A534V single mutation from clone #7 and the D262V mutation from clone #11 disrupted the Cdh1–A-motif interaction. (C) Cdh1 mutants are resistant to Acm1 in vivo. Cells carrying GAL-CDH1-m11 cannot grow in the presence of galactose, which induces expression of this constitutively active form of Cdh1. Overexpression of Acm1 suppressed the toxicity of Cdh1-m11, but not of the Cdh1-m11-A534V or -D262V mutants, indicating that these Cdh1 mutants were resistant to Acm1-mediated inhibition. (D) modelling of the yeast Cdh1 WD40 domain based on the known structures of other WD40 containing proteins. The 7-blade β-sheet propeller structure is shown with WD40 residues on the first and seventh blades important for DB interaction shown in red (top, D1: L255, P258; lower, D2: G535, D536). Amino-acid residues whose mutation disrupts the Cdh1–Acm1–A-motif interaction (with the exception of V388) are shown: P251, yellow; D262, green; S267 and L523, grey; V388, light blue; E485, orange; Y492 and L521, white; G513, pink; H514, hot pink; A534, blue; D526, cyan.

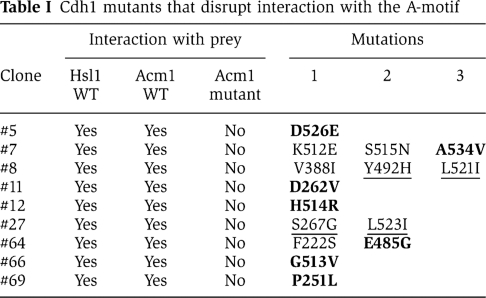

In initial attempts, we failed to identify Cdh1 WD40 domain residues important for the Acm1 A-motif interaction based on Cdh1 sequence conservation or modelling the yeast Cdh1 WD40 domain and mutating residues predicted to reside near the DB-binding surface. We therefore took a genetic approach by screening for mutations within Cdh1-Δ200 that disrupted the two-hybrid interaction with the Acm1 A-motif. We performed error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) mutagenesis on a two-hybrid plasmid encoding Cdh1-Δ200 fused to Ura3 so we could eliminate Cdh1 truncation mutations by selection for full-length proteins on medium lacking uracil. The Cdh1-Δ200–Ura3 fusion protein could interact with Hsl1, WT Acm1 and Acm1-N128-mdb1mdb3mkb in a two-hybrid assay and support growth on medium lacking uracil (Supplementary Figure S5, bottom panel).

A pool of CDH1-Δ200 mutants was generated by EP-PCR and introduced into the ACM1-N128-mdb1mdb3mkb yeast two-hybrid strain by gap-repair transformation (see Materials and methods). Recombination in vivo resulted in two-hybrid plasmids containing mutagenized CDH1-Δ200–URA3 in frame with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain. To avoid identifying Cdh1 mutant proteins that were grossly misfolded, only Cdh1 mutants that interacted by two-hybrid analysis with Hsl1 and WT Acm1, but not with Acm1-mdb1mdb3mkb, were analysed (see Materials and methods). Out of 114 Cdh1-Δ200–Ura3 mutants identified that could not interact with Acm1-mdb1mdb3mkb, only 9 could still interact with both Hsl1 and WT Acm1 (Supplementary Figure S5). DNA sequencing revealed that these nine mutants contained one to three amino-acid changes (Table I). In the case of multiple mutations, the corresponding single amino-acid mutants were created and tested for two-hybrid interaction with the different Gal4-activation domain fusion strains. Single amino-acid mutations that disrupted interaction with Acm1-N128-mdb1mdb3mkb were identified for clone #7 (A534V) and for clone #64 (E485G) (Table I, bold residues; Figure 3B) whereas two mutations were required for mutants #8 and #27 (Table I, mutations underlined).

Table 1. Cdh1 mutants that disrupt interaction with the A-motif.

We verified that these Cdh1 mutants were still functional in vivo by introducing the individual mutations into Cdh1-m11. Cdh1-m11 is a non-phosphorylatable version of Cdh1 that cannot be inhibited by the Cdc28 protein kinase, resulting in toxicity due to premature degradation of APC substrates during mitosis (Zachariae et al, 1998). Overexpression of Cdh1-m11, Cdh1-m11-A534V and Cdh1-m11-D262V all inhibited cell growth, indicating that the A534V and D262V mutations did not compromise Cdh1 function (Figure 3C). Overexpression of Acm1 can inhibit Cdh1-m11 and restore cell growth (Figure 3C) (Martinez et al, 2006; Dial et al, 2007). Interestingly, both Cdh1-m11-A534V and Cdh1-m11-D262V were resistant to Acm1 overexpression and still inhibited cell growth. Other single point mutants from Table I (shown in bold) gave similar results (data not shown). In contrast, a control mutant, F222S, which did not disrupt the Cdh1–Acm1 interaction (Table I), was still sensitive to Acm1 overexpression (Supplementary Figure S6). These findings demonstrated that Cdh1 mutants that could no longer recognize the A-motif could still promote APC substrate degradation but were resistant to Acm1-mediated inhibition. These Acm1-resistant Cdh1 mutants also demonstrate that the direct target of Acm1 is Cdh1, rather than the APC, as has been proposed for the APC inhibitor Emi1 (Miller et al, 2006).

Figure 3D shows a model of the yeast Cdh1 WD40 domain based on the known structures of other WD40 domain-containing proteins (see Materials and methods). Residues within the first and seventh WD40 repeats that are known to be important for DB recognition are shown in red. Interestingly, amino-acid residues affecting Acm1 A-motif recognition are also found within the first and seventh WD40 repeats and reside in close proximity to each other and to those residues that participate in DB recognition.

Converting Acm1 into an APCCdh1 substrate in vitro

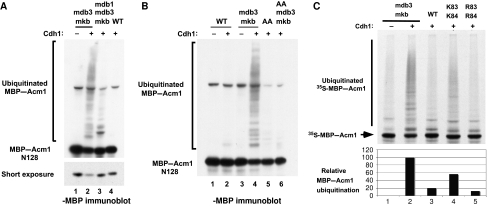

Because Acm1 binds Cdh1 via motifs (DB3 and the KEN box) that typically target APC substrates for degradation, we asked what other properties (besides the A-motif) might make Acm1 an APCCdh1 inhibitor rather than a substrate. One possibility is that with so many interaction motifs, Acm1 simply binds to Cdh1 too tightly or too rigidly for efficient ubiquitination. Thus, weakening the interaction between Acm1 and Cdh1 might convert Acm1 from a Cdh1 inhibitor into a substrate. Indeed, mutation of DB3 and the KEN box within Acm1 not only prevented its inhibition of Cdh1, but also converted Acm1 into an APCCdh1 substrate in vitro (Choi et al, 2008; Enquist-Newman et al, 2008). We confirmed that, unlike WT Acm1-N128, Acm1-N128-mdb3mkb was significantly ubiquitinated by APCCdh1 in vitro (Figure 4A, compare lanes 2 and 4; Figure 4B, lanes 1–4). This ubiquitination was virtually eliminated by mutation of DB1 (Figure 4A, compare lanes 2 and 3), suggesting that WT Acm1 and Acm1-mdb3mkb adopt different orientations in binding to Cdh1, allowing the latter to become an efficient APC substrate via recognition of DB1. Likewise, deletion of the amino terminal 57 amino acids (including DB1) resulted in inefficient ubiquitination of Acm1 58–128-mdb3mkb (data not shown). Unlike the mutation of DB3 and the KEN box, mutation of the A-motif did not promote APCCdh1-mediated Acm1 ubiquitination (Figure 4B, lane 5). These results suggest that weakening the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction does not necessarily convert the Cdh1-bound Acm1 into an APCCdh1 substrate and furthermore indicates that the A-motif does not by itself serve as a ubiquitination inhibitor. In agreement with this observation, Acm1 containing only the A- and K-motifs could not inhibit Hsl1 ubiquitination in vitro or degradation in vivo (Supplementary Figure S7).

Figure 4.

Ubiquitination of WT and mutant MBP–Acm1 in vitro. Ubiquitination reactions using WT or the indicated mutant forms of MBP–Acm1 were performed in the presence (+) or absence (−) of Cdh1, as indicated. Modified and unmodified MBP–Acm1 were detected by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibodies. (A) Ubiquitination of MBP–Acm1-N128-mdb3mkb depends on DB1. Lower panel, a shorter exposure of the unmodified substrate. (B) Mutation of the A-motif does not convert Acm1 into an APC substrate. The AA mutations eliminate ubiquitination of Acm1-N128-mdb3mkb by eliminating the interaction with Cdh1. (C) Introduction of lysine residues converts Acm1 into an APCCdh1 substrate. Lysines or arginines replaced asparagines at positions 83 and 84 in the K83 K84 and R83 R84 mutants. The lower panel shows a quantitation of the amount of modified Acm1 in each reaction.

We next examined whether WT Acm1 might avoid being ubiquitinated by APCCdh1 due to the placement of its ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues with respect to its Cdh1-binding motifs. Previous work found that the insertion of lysine residues near a cryptic HOS recognition site allowed an Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein variant to be recognized and ubiquitinated by the SCFHos/β−TrCP ligase during NF-κB activation (Tang et al, 2003). Although this is a three-dimensional question, we noticed the absence of lysine residues across a 28 amino-acid stretch between the A-motif and the KEN box in Acm1. To test whether lysine exclusion from this region might prevent Acm1 ubiquitination by APCCdh1, we inserted lysine residues into this region and examined whether the resulting proteins could now be ubiquitinated by APCCdh1 in vitro. Interestingly, the N83K N84K mutant was ubiquitinated (56% relative to Acm1-mdb3mkb), whereas the N83R N84R mutant, like WT Acm1, was not significantly ubiquitinated (Figure 4C). The N83K N84K mutant interacted normally with Cdh1 in both the two-hybrid and the in vitro Cdh1-binding assays (Supplementary Figure S8). It should be noted that this Acm1 mutant could still contribute to Cdh1 inhibition in the Hsl1–Ura3 stability assay (data not shown), suggesting that it is not a full APCCdh1 substrate in vivo. Introductions of lysine residues at positions 70/72 or 92/93 were less effective in promoting Acm1 ubiquitination in vitro (Supplementary Figure S9). These findings suggest that the positioning of ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues can influence the extent of Acm1 ubiquitination in vitro.

Converting an APCCdh1 substrate into an APCCdh1 inhibitor by removing its ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues

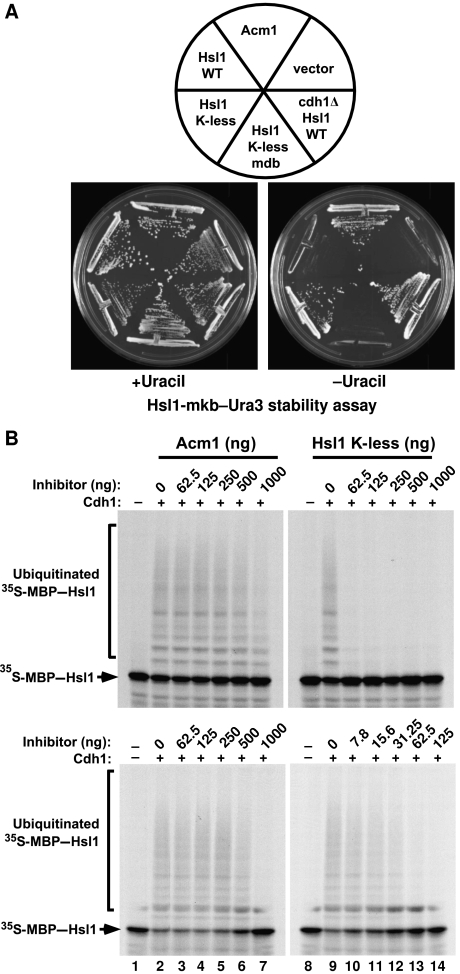

The previous result raised the possibility that the removal of lysines from a bona fide APCCdh1 substrate might convert it into an APC inhibitor. As a test for this hypothesis, we mutated to arginine all lysines other than the one in the KEN box of the APC substrate Hsl1667−872 to create ‘Hsl1-K-less.’ This mutant protein could bind to Cdh1 with high affinity both in vivo and in vitro and, although expressed at lower levels than WT Hsl1, was stabilized in G1-arrested cells (data not shown). In contrast, wild-type Hsl1 was expressed at high levels in asynchronous cells but was undetectable in G1-arrested cells (data not shown). Interestingly, Hsl1-K-less, like Acm1, could inhibit APCCdh1 activity in the Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 strain, allowing cell growth on medium lacking uracil whereas WT Hsl1 could not (Figure 5A). APCCdh1 inhibition required the Hsl1-K-less DB, which is important for tight binding of Hsl1 to Cdh1 (Burton and Solomon, 2001; Burton et al, 2005).

Figure 5.

Removal of lysine residues can convert Hsl1 from an APC substrate into an APC inhibitor. (A) Hsl1 ‘K-less’ inhibits the APCCdh1 in vivo. WT Acm1, WT Hsl1, K-less Hsl1 or K-less Hsl1-mdb were expressed in cells expressing an Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 reporter, which allows cell growth in the absence of added uracil when APCCdh1 activity is low. Only Acm1 and Hsl1-K-less inhibited Cdh1 to allow cell growth. (B) Hsl1-K-less is a potent APCCdh1 inhibitor in vitro. The indicated amounts of Acm1 or Hsl1-K-less were pre-incubated with APCCdh1 before the addition of 35S-MBP–Hsl1 and other ubiquitination assay components. Modified and unmodified MBP–Hsl1 were visualized by autoradiography. Note that lower concentrations of Hsl1-K-less were utilized in the lower right panel.

We next examined whether Hsl1-K-less could inhibit APCCdh1 in vitro. Hsl1-K-less was a very potent inhibitor in this assay, with strong inhibition of 35S-MBP–Hsl1 ubiquitination observed with as little as 62.5 ng of Hsl1-K-less (Figure 5B, right panels). A similar level of APCCdh1 inhibition by Acm1 required 1 μg of protein (Figure 5B, left panels). As expected, APCCdh1 inhibition by Hsl1-K-less required its DB (data not shown). In contrast to Hsl1-K-less, WT Hsl1 was a very inefficient inhibitor of APCCdh1-mediated ubiquitination (Supplementary Figure S10) in agreement with its inability to inhibit Cdh1 in the in vivo assay. We quantitated the extent of APCCdh1 inhibition by Acm1 and Hsl1-K-less by determining the relative amounts of unmodified 35S-MBP–Hsl1 remaining at the end of each reaction. Almost complete inhibition (∼95%) was observed with either 1 μg of Acm1 or 125 ng of Hsl1-K-less (Supplementary Figure S11, left panels). Reducing the amount of Cdh1 in these assays lowered the amount of Acm1 required for the inhibition but had little effect on the concentration of Hsl1-K-less required for inhibition (Supplementary Figure S11, right panels).

Discussion

APC activity is controlled not only by regulating Cdc20 and Cdh1 levels and binding to the APC, but also by pseudosubstrate inhibition. We have explored the interaction of Cdh1 with its inhibitor Acm1 in order to understand the features that make it an APC inhibitor and that distinguish it from an APC substrate. In addition to DB3 and the KEN box of Acm1, we have identified the A-motif, in particular E65 and E66, as critical both for Cdh1 binding and the inhibition of APCCdh1. We found that Cdh1 WD40 domain residues involved in the recognition of the A-motif are distinct from those involved in interacting with the DB and KEN box of Acm1 and the APC substrate Hsl1. Finally, the positioning of ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues within a Cdh1-bound protein can influence its fate as the insertion of lysines within Acm1 (K83 K84) near the KEN box and A-motif promoted ubiquitination of Acm1 whereas removal of lysines from Hsl1 converted it into a potent APC inhibitor.

The A-motif of Acm1

We identified the A-motif within Acm1 by mutagenesis and screening for the loss of the Cdh1–Acm1-N128 two-hybrid interaction. These residues, together with DB3 and the KEN box contributed to Cdh1 binding in vitro and were critical for APCCdh1 inhibition in vivo. Examination of full-length Acm1 revealed the presence of an additional carboxyl-terminal motif (the K-motif) that also promoted Acm1 association and inhibition of Cdh1 independently of the A-motif. The K-motif only affected Cdh1 binding in the context of full-length Acm1 (and not in the C81 fragment), suggesting that this motif exhibits a low affinity interaction with Cdh1 (Supplementary Figure S3).

Interestingly, E65 and E66 within the Acm1 A-motif (EETAE) resemble a Cdh1-interaction motif identified in human Claspin (SAEEENKENL; motif represented by underlined residues) (Bassermann et al, 2008). Claspin is an adaptor protein that promotes the association of the ATR protein kinase with the Chk1 protein kinase during the DNA-damage checkpoint response in higher eukaryotes and was recently found to be an APCCdh1 substrate. Mutation of EEN or ENL in Claspin stabilized the protein and disrupted its association with Cdh1 (Bassermann et al, 2008). We speculate that the A-motif of Acm1 may not be an inhibitory motif per se. Rather, it may simply provide another way for proteins to bind to Cdh1. The fate of these proteins—inhibition or ubiquitination—would also depend on their other features. This interpretation is consistent with the finding that full-length Acm1 containing only the A- and K-motifs was unable to inhibit APCCdh1 activity in the in vivo and in vitro assays (Supplementary Figure S7). Furthermore, mutation of the A-motif did not result in APCCdh1-mediated ubiquitination of Acm1.

Recognition of the A-motif by Cdh1

A mutational analysis indicated that Cdh1 residues other than those that interact with DBs and KEN boxes are necessary for recognizing the A-motif. A previous study identified a quadruple mutant (termed D12) that eliminated binding of human Cdh1 to a DB. We confirmed using a two-hybrid assay that the corresponding residues in yeast Cdh1 are essential for recognition of Hsl1. Cdh1-Δ200–D12 still interacted with Acm1, but not with Acm1-mutA, suggesting that additional residues within the Cdh1 WD40 domain were responsible for this interaction. We identified several Cdh1 amino-acid mutations that disrupted recognition of the A-motif but not of the DB or KEN box. Intriguingly, the mutated amino acids are predicted to lie very close to those that participate in DB binding in the first and seventh WD40 repeats of Cdh1, raising the possibility that DB3, the KEN box and the A-motif may bind as a larger unit to a single patch on the surface of Cdh1. We do not anticipate that all of the identified Cdh1 residues interact directly with E65 and E66 of Acm1. Rather, some of the mutations likely alter the precise positioning of neighbouring side chains that directly recognize the A-motif. These structural alterations must be minor since these mutants still interacted with DB and KEN box motifs and were functional in the Cdh1-m11 toxicity assay. Nevertheless, they rendered Cdh1-m11 resistant to inhibition by Acm1 in vivo (Figure 3C). Surprisingly, wild-type Cdh1 containing either the A534V or the D262V mutation was active in a ubiquitination assay in vitro but could still be inhibited by Acm1 (data not shown). We currently do not know the reason for the discrepancy between these two assays; perhaps Cdh1-m11 inhibition in vivo requires a higher level of Acm1 activity than WT Cdh1 in vitro. In the future, we hope to pinpoint the Cdh1 amino acids that directly interact with E65 and E66 within the A-motif. Ultimately, this may require the determination of the co-crystal structure of the Cdh1 WD40 domain with Acm1.

A number of observations suggest that the Cdh1 WD40 residues LXXP and GD (mutated in D1 and D2, respectively) shown to participate in DB interaction (Kraft et al, 2005) also appear to be involved in KEN box recognition. First, Cdh1-Δ200–D12 did not interact with Hsl1 or Acm1-mutA in either the two-hybrid assay (Figure 3A) or in an in vitro binding assay (data not shown) even though both proteins contained a functional KEN box known to be important for binding to WT Cdh1. Second, we have found that Hsl1 with only a KEN box or only a DB could not interact with Cdh1–D2 and only interacted weakly with the Cdh1–D1 mutant, although both Hsl1 mutants can interact with WT Cdh1. In contrast, WT Hsl1 interacted well with either Cdh1 mutant (data not shown). These findings suggest that the DB and KEN box interactions with these Cdh1 residues are likely to be inter-dependent.

What distinguishes an APC substrate from an APC inhibitor?

It is not surprising that Acm1 binds to Cdh1 tightly and via multiple interaction motifs since the purpose of a pseudosubstrate inhibitor is to engage Cdh1 (or Cdc20) to prevent substrate degradation. Indeed, mutation of any of the key interaction motifs—DB3, the KEN box and the A-motif—significantly reduces or eliminates APCCdh1 inhibition by Acm1. A similar loss of APC inhibition has been found for the pseudosubstrate inhibitors Mad3/BubR1 and Emi1 upon mutation of their KEN boxes and the DB, respectively (Miller et al, 2006; Burton and Solomon, 2007; Malureanu et al, 2009). It has been proposed that the very tight binding of Acm1 to Cdh1 is also what prevents Acm1 from being ubiquitinated by APCCdh1 (Choi et al, 2008), perhaps by severely limiting the flexibility of the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction. This suggestion received support from the observation that mutation of DB3 and the KEN box allows Acm1 ubiquitination by APCCdh1 in vitro (Choi et al, 2008; Enquist-Newman et al, 2008). However, we found that this ubiquitination was largely dependent upon DB1 as mutation of this motif (Figure 4) or its deletion in Acm1 58–128 (data not shown) greatly diminished the extent of Acm1-mdb3mkb ubiquitination in vitro. However, the physiological importance of DB1 in APCCdh1-mediated ubiquitination appears to be minimal. Acm1 normally binds to Cdc20 via DB1, leading to its ubiquitination by APCCdc20, whereas it binds to Cdh1 via DB3 and the KEN box (and the A-motif), leading to inhibition of APCCdh1. Thus, Acm1 appears to bind to Cdc20 and Cdh1 in two very different orientations, with different consequences: ubiquitination or inhibition. When Acm1 has an intact N-terminus, mutation of DB3 and the KEN box forces Acm1 to bind to Cdh1 in the DB1-dependent orientation it normally adopts in binding to Cdc20, thereby resulting in its ubiquitination. Interestingly, DB1 appears not to be required for the APCCdh1-mediated ubiquitination of certain Acm1-mdb3mkb truncation mutants (Choi et al, 2008; Enquist-Newman et al, 2008), suggesting that Acm1 truncations can also influence the orientation of the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction. These observations suggest that Acm1 is sensitive to mutational analysis with some mutations altering the orientation of the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction resulting in ubiquitination rather than inhibition.

A similar situation was observed for Emi1 where mutation of the ZBR converted Emi1 from an APCCdh1 inhibitor into an APCCdh1 substrate dependent upon the Emi1 DB (Miller et al, 2006). It is unclear how the ZBR inhibits APC activity. Perhaps, the ZBR forces Emi1 to bind to APCCdh1 in an orientation that shields the DB or surrounding lysine residues from APC-mediated ubiquitination.

Besides tight binding, another way in which pseudosubstrate inhibitors might avoid APC-mediated ubiquitination and subsequent degradation is by lacking well-positioned ubiquitin acceptor lysine residues. We found that insertion of lysine residues at positions 83 and 84 within Acm1, approximately in the middle of the region flanked by the A-motif and the KEN box, promoted modest ubiquitination of Acm1 by APCCdh1 in vitro, whereas insertion of lysines closer to the A-motif (K70 K72) or the KEN box (K92 K93) was less effective, suggesting that the positioning or orientation of these lysines influences the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2–APC complex to Acm1. These mutations had no apparent effect on the affinity of the Acm1–Cdh1 interaction. Despite its ubiquitination by APCCdh1 in vitro, Acm1-K83K84 was still an effective APCCdh1 inhibitor in vivo in the Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 stability assay (data not shown), suggesting that there may be a balance between how tightly a protein is bound to Cdh1 and its extent of ubiquitination that ultimately determines if the protein behaves as an inhibitor or a substrate. It will be of interest to see if further lysine insertion mutations can convert Acm1 strictly into an APCCdh1 substrate.

We found that removal of lysines from the APCCdh1 substrate Hsl1 (Hsl1-K-less) converted it into a potent APCCdh1 inhibitor both in vivo and in vitro. Lack of ubiquitination may serve two purposes. First, it prevents degradation of the inhibitor, but perhaps more importantly, it may slow dissociation of the inhibitor–Cdh1 complex, thereby making the inhibitor more potent. We infer that ubiquitination accelerates dissociation since Hsl1-K-less is a much better APCCdh1 inhibitor in vitro than WT Hsl1 despite having identical interaction motifs (a DB and a KEN box). Hsl1-K-less is also a strong APCCdh1 inhibitor in vivo, whereas wild-type Hsl1 is not, even though Hsl1-K-less is expressed at a much lower level than wild-type Hsl1. A similar result was obtained in fission yeast where a K-less form of the APC inhibitor Mes1 was found to be a potent APC inhibitor that formed a stable ternary complex with APCCdc20 (Kimata et al, 2008b), although it is uncertain whether Mes1 is normally ubiquitinated by APCCdc20 or a different form of the APC.

It is unclear why Hsl1-K-less is a more potent inhibitor than Acm1 in the in vitro ubiquitination assay (Figure 5). It is possible that Acm1 mono-ubiquitination (Choi et al, 2008) can promote a low level of Acm1 release from APCCdh1 in this assay. Another explanation may be that Hsl1-K-less targets APCCdh1 complexes whereas Acm1 may target free Cdh1. The APC is present at a lower concentration than Cdh1 in the ubiquitination assays, so less Hsl1-K-less would be needed to titrate the APC than the Cdh1 in the reaction. This hypothesis is plausible as Hsl1 binding to Cdh1 is known to enhance the binding of Cdh1 to the APC (Burton et al, 2005). Furthermore, reducing the amount of Cdh1 in a ubiquitination reaction reduced the amount of Acm1 needed to inhibit ubiquitination, but had little effect on the amount of Hsl1-K-less needed (Supplementary Figure S11).

In conclusion, pseudosubstrate APC inhibitors bind Cdc20 and Cdh1 primarily through the DB and KEN box motifs in order to block substrate association. Additional interactions, such as through Acm1's A-motif, enhance this interaction and contribute significantly to the ability of Acm1 to act as an inhibitor. The lack of Acm1 ubiquitination, possibly resulting from the inaccessibility of its lysines to the APC-bound E2 enzyme, stabilizes the Acm1–Cdh1 complex and further contributes to making Acm1 a potent APC inhibitor.

Materials and methods

Yeast strain and plasmid constructions

The GAL-myc-CDH1-m11 plasmid (pWS526) (Schwab et al, 2001) and the yeast two-hybrid strains pJ69-4a and pJ69-4a (James et al, 1996) were kind gifts from Dr Wolfgang Seufert (University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Denmark) and from Dr Stanley Fields (University of Washington, Seattle, WA), respectively. The SNF4-pACT, pAS2 and pACTII plasmids were kind gifts from Dr Steven Elledge (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). All strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1 and are derivatives of W303-1A (MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 can1-100 ura3-1 trp1-1 ssd1-d) (Rothstein, 1991) unless otherwise specified.

The cdh1Δ strains and the GAL-ACM1-TAP plasmid were previously described (Ostapenko et al, 2008). WT and mdb3mkb versions of ACM1-, ACM1-N128- and ACM1-C81-pMALc-2 plasmids were described previously (Ostapenko et al, 2008). WT and mdb3mkb versions of ACM1-58-128 in pMALc-2 were constructed similarly with sequences encoding amino acids 58–128 in frame and downstream of the MBP coding sequence. ACM1 and ACM1-N128 were constructed in frame with the GAL4-activation domain in the yeast two-hybrid pACTII vector. Mutations within DB1 (8RTIL → 8ATIA), DB3 (119RIAL → 119AIAA) and the KEN box (98KEN → 98AAA) of ACM1 or ACM1-N128 in either the pACTII or pMALc-2 plasmids were introduced by inverse PCR.

WT HSL1667−872 and HSL1667−872 mdbmkb pACTII plasmids were made by PCR of HSL1 from the corresponding pMALc-2 plasmids (Burton and Solomon, 2001) and cloned into pACTII in frame with the GAL4-activation domain. Throughout this study, HSL1667−872 is referred to as HSL1. The Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 strain was made by introducing the mkb (775KENEGPE → 775AAAEGPA) mutation into the ADH1-HSL1-URA3-HA plasmid (pVT71) (Burton et al, 2005) by Quikchange mutagenesis (Stratagene) and integration of this plasmid into the TRP1 locus following linearization with Ava I. HSL1-K-less was synthesized by Blue Heron Biotechnology (Bothell, WA). Twenty lysines in Hsl1 (excluding the lysine residue in the KEN box) were mutated to arginines. Every other lysine codon was mutated to AGA or CGT. HSL1-K-less was inserted into the pACTII and pMALc-2 plasmids. HSL1-K-less-mdb (828RAAL → 828AAAA)-pACTII was made by inverse PCR using HSL1-K-less-pACTII. For the alanine-scanning mutagenesis of amino acids 58–128 of Acm1, nucleotides encoding charged or polar residues within five amino-acid windows were mutated to alanines in ACM1-N128-mdb3mkb pACTII by inverse PCR to generate Acm1 mutants A through I (see Figure 1A for amino-acid changes). The A-motif mutations (Mut. A) were also introduced into ACM1-pMALc-2 by inverse PCR. Where indicated, the Acm1 AA mutant corresponds to the E65A E66A double mutation. Mutants J (186SRSTDD → 186AAAAAA) and K (196KVVRK → 196AVVAA) were made by inverse PCR of WT or Mut. A ACM1-pACTII. The J and K mutations were also introduced into the indicated ACM1-pMALc-2 constructs by inverse PCR. Note that the genes inserted into the pACTII plasmid were used both in the yeast two-hybrid interaction assays as well as in the Hsl1-mkb–Ura3 stability assays.

The CDH1-Δ200-pAS2 plasmid expressed amino acids 201–566 of Cdh1 in frame with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain encoded by the pAS2 plasmid. CDH1-Δ200-D12-pAS2 was constructed by inverse PCR of CDH1-Δ200 pAS2 in which the D1 mutations (255LDAP → 255VDAA) and the D2 mutations (534GD → 534AA) were introduced sequentially. The D1 and D2 mutations were designed based on a sequence alignment of Cdh1 from numerous organisms (Kraft et al, 2005). CDH1-Δ200-URA3 was cloned into pAS2 by PCR from pVT54, which contains an in frame CDH1–URA3 fusion (kind gift of Vasiliki Tsakraklides).

All clones of ACM1, HSL1 and CDH1 generated by PCR or inverse PCR were sequenced in their entirety to ensure that only desired mutations were present. Information regarding the oligonucleotides used is available upon request.

EP-PCR mutagenesis of CDH1-Δ200 and yeast two-hybrid screening

The Cdh1 WD40 domain was mutagenized by EP-PCR using CDH1-Δ200-URA3-pAS2 as the template under previously described conditions (Burton et al, 2005). The sense primer annealed to the GAL4 DNA-binding domain and HA tag and extended to the CDH1 start codon. The antisense primer annealed to URA3 and extended to the last amino acid of CDH1. EP-PCR conditions were as follows: 2 μg/ml CDH1-Δ200-URA3-pAS2, 0.2 μM of each primer, 1 mM dTTP, 1 mM dCTP, 0.2 mM dATP, 0.2 mM dGTP, 6 mM MgCl2, 50 μM MnCl2, 1 × PCR buffer (−MgCl2) (Invitrogen) and 0.5 U/μl Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs). After 16 cycles of amplification, 1 ml of product was purified using a Qiagen PCR purification column (Qiagen, Inc.) and co-transformed into YJB1212 with ∼2.5 μg of gapped CDH1-Δ200-URA3-pAS2 vector. The gapped vector was prepared by digestion of CDH1-Δ200-URA3-pAS2 with Nde I and Sal I to release the CDH1-Δ200 insert, followed by purification of the pAS2 vector backbone from an agarose gel using a Qiagen gel extraction kit. Recombination in yeast cells resulted in two-hybrid plasmids containing mutagenized CDH1-Δ200-URA3 in frame with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain. Yeast transformants were plated at ∼200 colonies per plate onto medium lacking tryptophan, leucine and uracil. The resulting colonies were replica plated onto medium lacking histidine, adenine, tryptophan, leucine and uracil to detect the Cdh1–Acm1 two-hybrid interactions. Colonies that did not grow on the replica plate were isolated from the corresponding colony on the master plate and induced to lose the ACM1-mdb1mdb3mkb-pACTII plasmid by growth in medium containing leucine. These strains were mated with strains expressing HSL1, ACM1 WT and ACM1-mdb1mdb3mkb prey strains and re-tested for the two-hybrid interaction on selective medium. Plasmids were isolated from the CDH1-Δ200-URA3 mutant strains that showed interaction with Hsl1 and Acm1 WT, but not with Acm1-mdb1mdb3mkb. Sequencing was performed by the Yale Keck DNA sequencing facility (Yale University, New Haven, CT). In cases where clones contained more than one mutation, each individual mutation was introduced into CDH1-Δ200-URA3-pAS2 by inverse PCR and re-tested for two-hybrid interaction by mating with the different prey strains.

In vitro binding and ubiquitination assays

Recombinant MBP–Acm1 full-length, N128 and C81 fusion proteins were produced and purified from E. coli as previously described (Ostapenko et al, 2008). MBP–Hsl1 and the different versions of MBP–Acm1 were radiolabeled with 35S-methionine (Perkin-Elmer) using the TNT Quick-coupled transcription/translation system (Promega). Binding assays using 6xHis–Cdh1 bound to Talon Beads with different recombinant MBP–Acm1 fusion proteins were performed as previously described (Ostapenko et al, 2008); bound Acm1 was detected by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibodies (New England Biolabs). In vitro ubiquitination assays using 35S-MBP–Hsl1 or 35S-MBP–Acm1 were done as previously described (Ostapenko et al, 2008). Quantitation of ubiquitinated and unmodified substrate was performed by PhosphorImage analysis. Ubiquitination of recombinant MBP–Acm1 was carried out similarly using ∼0.1 μg of each recombinant fusion protein; MBP–Acm1 was detected by immunoblotting with anti-MBP antibodies. For inhibition of Hsl1 ubiquitination in vitro, the indicated amounts of recombinant MBP–Acm1 or MBP–Hsl1-K-less were pre-incubated with APCCdh1 for 10 min on ice before the addition of the APC substrate.

Homology modelling

Multiple runs of homology modelling of the yeast Cdh1 WD40 domain (residues 248–544) were performed using the MODELLER program (Sali and Blundell, 1993) and the automated modelling server I-TASSER (Zhang, 2008), which consistently ranked as the top server in the recent CASP7 and CASP8 modelling contests (Battey et al, 2007). Before using MODELLER, a multiple sequence alignment was carried out using the WD40 domains of Cdh1, Lissencephaly 1 (LIS1) and transducin using the MUSCLE program (Edgar, 2004). The aligned sequences were input into MODELLER using the crystal structures of LIS1 (PDB ID: 1VYH) and transducin (PDB ID: 1A0R) as multiple templates, which improved the quality of the modelling. Two runs of I-TASSER modelling were performed, each using 4–6 WD40 domain structures as templates (PDB IDs for run 1: 3OW8, 3DM0, 3IYT and 1VYH; run 2: 1NR0, 1VYH, 1TBG, 1NR0, 1GXR and 1PGU). The quality of the homology modelling result is high as indicated by (i) the clear sequence alignment of the Cdh1 WD40 domain and those of the template proteins and (ii) the high consistency of the resulting models produced by MODELLER and I-TASSER using the many different template structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Elledge, Stan Fields, Wolfgang Seufert and Vasiliki Tsakraklides for plasmids and strains. We thank Tom Steitz for use of the French Press. We thank Mark Hochstrasser, Denis Ostapenko and Ruiwen Wang for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants 09GRNT2370047 from the American Heart Association Founders Affiliate and GM088272 from the NIH awarded to MJS.

Author contributions: MJS and JLB designed the experiments, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. YX contributed the structural model in Figure 3 and the corresponding text, and reviewed the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Bassermann F, Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Busino L, Peschiaroli A, Pagano M (2008) The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell 134: 256–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battey JN, Kopp J, Bordoli L, Read RJ, Clarke ND, Schwede T (2007) Automated server predictions in CASP7. Proteins 69(Suppl 8): 68–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton JL, Solomon MJ (2001) D box and KEN box motifs in budding yeast Hsl1p are required for APC-mediated degradation and direct binding to Cdc20p and Cdh1p. Genes Dev 15: 2381–2395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton JL, Solomon MJ (2007) Mad3p, a pseudosubstrate inhibitor of APCCdc20 in the spindle assembly checkpoint. Genes Dev 21: 655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton JL, Tsakraklides V, Solomon MJ (2005) Assembly of an APC-Cdh1-substrate complex is stimulated by engagement of a destruction box. Mol Cell 18: 533–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo T, Pagano M (2004) The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 739–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E, Dial JM, Jeong DE, Hall MC (2008) Unique D box and KEN box sequences limit ubiquitination of Acm1 and promote pseudosubstrate inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex. J Biol Chem 283: 23701–23710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dial JM, Petrotchenko EV, Borchers CH (2007) Inhibition of APCCdh1 activity by Cdh1/Acm1/Bmh1 ternary complex formation. J Biol Chem 282: 5237–5248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1792–1797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enquist-Newman M, Sullivan M, Morgan DO (2008) Modulation of the mitotic regulatory network by APC-dependent destruction of the Cdh1 inhibitor Acm1. Mol Cell 30: 437–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotzer M, Murray AW, Kirschner MW (1991) Cyclin is degraded by the ubiquitin pathway. Nature 349: 132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MC, Jeong DE, Henderson JT, Choi E, Bremmer SC, Iliuk AB, Charbonneau H (2008) Cdc28 and Cdc14 control stability of the anaphase-promoting complex inhibitor Acm1. J Biol Chem 283: 10396–10407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A, Ciechanover A (1998) The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem 67: 425–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrasser M (1996) Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet 30: 405–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JY, Reimann JD, Sorensen CS, Lukas J, Jackson PK (2002) E2F-dependent accumulation of hEmi1 regulates S phase entry by inhibiting APCCdh1. Nat Cell Biol 4: 358–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa D, Goto M, Yamashita A, Yamano H, Yamamoto M (2005) Fission yeast Mes1p ensures the onset of meiosis II by blocking degradation of cyclin Cdc13p. Nature 434: 529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Halladay J, Craig EA (1996) Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics 144: 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Baxter JE, Fry AM, Yamano H (2008a) A role for the Fizzy/Cdc20 family of proteins in activation of the APC/C distinct from substrate recruitment. Mol Cell 32: 576–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Trickey M, Izawa D, Gannon J, Yamamoto M, Yamano H (2008b) A mutual inhibition between APC/C and its substrate Mes1 required for meiotic progression in fission yeast. Dev Cell 14: 446–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King EM, van der Sar SJ, Hardwick KG (2007) Mad3 KEN boxes mediate both Cdc20 and Mad3 turnover, and are critical for the spindle checkpoint. PLoS One 2: e342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft C, Vodermaier HC, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F, Peters JM (2005) The WD40 propeller domain of Cdh1 functions as a destruction box receptor for APC/C substrates. Mol Cell 18: 543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malureanu LA, Jeganathan KB, Hamada M, Wasilewski L, Davenport J, van Deursen JM (2009) BubR1 N terminus acts as a soluble inhibitor of cyclin B degradation by APC/CCdc20 in interphase. Dev Cell 16: 118–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JS, Jeong DE, Choi E, Billings BM, Hall MC (2006) Acm1 is a negative regulator of the CDH1-dependent anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol 26: 9162–9176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Summers MK, Hansen DV, Nachury MV, Lehman NL, Loktev A, Jackson PK (2006) Emi1 stably binds and inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome as a pseudosubstrate inhibitor. Genes Dev 20: 2410–2420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostapenko D, Burton JL, Wang R, Solomon MJ (2008) Pseudosubstrate inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex by Acm1: regulation by proteolysis and Cdc28 phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 28: 4653–4664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM (2006) The anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome: a machine designed to destroy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 644–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroski MD (2008) The ubiquitin system, disease, and drug discovery. BMC Biochem 9 (Suppl 1): S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger CM, Kirschner MW (2000) The KEN box: an APC recognition signal distinct from the D box targeted by Cdh1. Genes Dev 14: 655–665 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann JD, Freed E, Hsu JY, Kramer ER, Peters JM, Jackson PK (2001) Emi1 is a mitotic regulator that interacts with Cdc20 and inhibits the anaphase promoting complex. Cell 105: 645–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimann JD, Jackson PK (2002) Emi1 is required for cytostatic factor arrest in vertebrate eggs. Nature 416: 850–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R (1991) Targeting, disruption, replacement, and allele rescue: integrative DNA transformation in yeast. Methods Enzymol 194: 281–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL (1993) Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 234: 779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Duncan PI, Rauh NR, Sauer G, Fry AM, Nigg EA, Mayer TU (2005) Xenopus polo-like kinase Plx1 regulates XErp1, a novel inhibitor of APC/C activity. Genes Dev 19: 502–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M, Neutzner M, Mocker D, Seufert W (2001) Yeast Hct1 recognizes the mitotic cyclin Clb2 and other substrates of the ubiquitin ligase APC. EMBO J 20: 5165–5175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen CS, Lukas C, Kramer ER, Peters JM, Bartek J, Lukas J (2001) A conserved cyclin-binding domain determines functional interplay between anaphase-promoting complex-Cdh1 and Cyclin A-Cdk2 during cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 21: 3692–3703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Pavlish OA, Spiegelman VS, Parkhitko AA, Fuchs SY (2003) Interaction of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 with SCFHOS/beta−TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligase regulates extent of NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 278: 48942–48949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton BR, Toczyski DP (2006) Precise destruction: an emerging picture of the APC. Genes Dev 20: 3069–3078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H (2007) Cdc20: a WD40 activator for a cell cycle degradation machine. Mol Cell 27: 3–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae W, Schwab M, Nasmyth K, Seufert W (1998) Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science 282: 1721–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y (2008) I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.