Abstract

Postantibiotic effects (PAEs) of rifapentine, isoniazid, and moxifloxacin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis ATCC 27294 were studied using a radiometric culture system. Rifapentine at 20 mg/liter gave the longest PAE (104 h) among the drugs used alone. The combinations of rifapentine plus isoniazid, rifapentine plus moxifloxacin, and isoniazid plus moxifloxacin gave PAEs of 136.5, 59.0, and 8.3 h, respectively.

Postantibiotic effect (PAE) refers to the continued suppression of bacterial growth following limited exposure of organisms to an antimicrobial agent (3, 24). The significant PAE of a single drug or a combination of drugs may allow wider dosing intervals without the loss of therapeutic efficacy (8). In managing patients with tuberculosis, administration of drugs at intermittent intervals would reduce cost and possibly toxicity of drugs, as well as enhance adherence through greater feasibility of directly observed therapy (13). Earlier work a few decades ago on pulsed exposure of rifampin and isoniazid for 6 to 96 h provided some therapeutic hints on such issues (9-12).

We have examined the PAEs of rifampin, isoniazid, amikacin, streptomycin, ethambutol, ofloxacin, and pyrazinamide against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a previous study (6). We subsequently embarked on this study to assess the PAEs of rifapentine, moxifloxacin, and isoniazid. The former two agents could be regarded as new antituberculosis drugs.

The standard strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) chosen for this study was susceptible to all three drugs tested. The MICs of rifapentine, isoniazid, and moxifloxacin against the standard strain of M. tuberculosis were 0.125, 0.06, and 0.25 mg/liter, respectively, as determined by the broth macrodilution method. The PAEs of the three antituberculosis agents were assessed using drug concentrations falling into the likely therapeutic ranges in humans (7, 17, 19-21): rifapentine (10 to 20 mg/liter), isoniazid (2 mg/liter), and moxifloxacin (1 to 2 mg/liter). Rifapentine and moxifloxacin drug powders for testing were gifts from d'Aventis Pharmaceutical International (Romainville, France) and Bayer Pharmaceutical (Wuppertal, Germany), respectively. Isoniazid drug powder for testing was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). The stock solutions were prepared in appropriate solvents, stored at −70°C in 1.0-ml aliquots, and used within 6 months. For each experiment, aliquots of the stock solutions were thawed and subsequently diluted in Middlebrook 7H9 broth supplemented with 2% glycerol and 10% oleic acid-dextrose catalase (Difco Laboratories).

The PAEs of the three drugs alone and in combination were determined using a previously established radiometric culture method (14). A homogenous suspension of bacterial cells matching that of McFarland standard 1 was obtained from a 3-week-old culture and stored at −40°C in 1.0-ml aliquots. For each experiment, a single vial of cells was thawed quickly at 37°C and inoculated into 10 ml of BACTEC 12B medium supplemented with 2.5% Panta reconstituting fluid. This suspension was incubated for 15 days at 37°C for use as the inoculum, which contained mycobacteria in the late logarithmic phase of the growth curve. Prior to use, the seed vial was sonicated for 3 min in a Branson ultrasonic water bath in order to minimize bacterial aggregates. Nine milliliters of the various drugs, with concentrations equivalent to 4 to 160 times the MICs of the different drugs, either alone or in combination, and a drug-free control were inoculated with 1.0 ml of the prepared seed (final inoculum, 2 × 106 to 7 × 106 CFU/ml). After 2 h of incubation, drug removal was accomplished by a 1:1,000 dilution (1.0 ml in 9.0 ml and then 0.05 ml in 4.95 ml) into fresh prewarmed BACTEC 12B medium supplemented with 2.5% Panta reconstituting fluid. Controls containing similarly diluted drugs and serial dilutions of previously unexposed organisms were included to monitor any residual antibiotic effects and killing effects. All experiments were carried out thrice in duplicate on different days. Inoculated BACTEC vials were incubated and read daily on a BACTEC 460 instrument until the BACTEC growth index (GI) reached 999. The viable numbers of organisms, immediately before and after drug exposure, were determined by plating appropriate dilutions onto Middlebrook 7H11 agar slopes in screw-cap flasks. The agar slopes were incubated for 3 to 4 weeks, and colonies were counted.

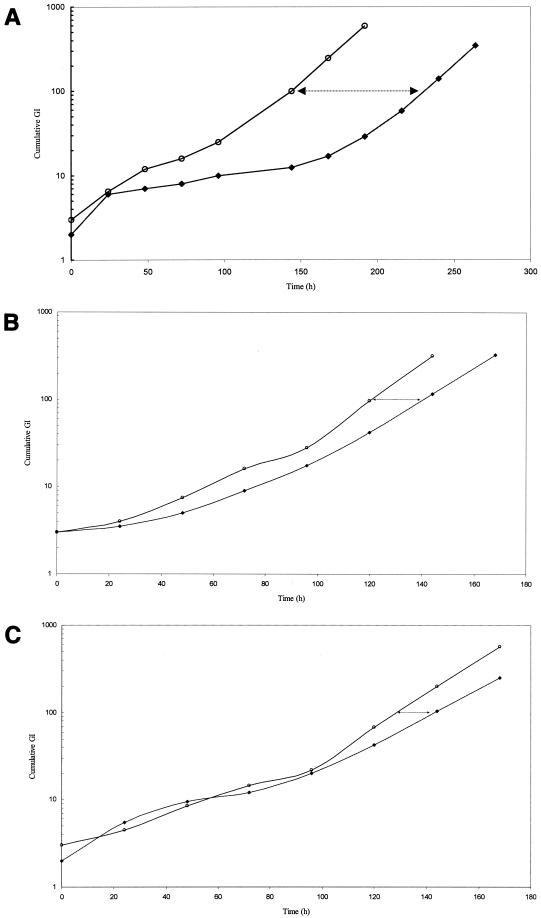

Quantitation of PAE employing the GI readings was calculated using the formula PAE = T − C, where T and C represent, respectively, the time for the exposed (T) and control (C) cultures to reach the cumulative GI values of 100 (16). A set of representative graphs on the demonstration of PAE of rifapentine (10 mg/liter), isoniazid (2 mg/liter), and moxifloxacin (2 mg/liter) is shown in Fig. 1A, B, and C, respectively. Killing effects were detected after 2 h of exposure to some of the drugs used individually and in combinations. To avoid overestimation of PAEs, appropriate diluted unexposed controls with inoculum size closest to the respective exposed culture as well as similarly diluted drug controls were selected for the calculation. The PAEs shown in Table 1 represent net PAEs corrected for residual antibiotic effects and killing effects.

FIG. 1.

(A) Regrowth curves of M. tuberculosis H37Rv following 2 h of exposure to rifapentine (10 mg/liter). ○, cumulative GI of residual control; ♦, cumulative GI of exposed culture. The time interval between cumulative GI lines (arrows) denotes the PAE. (B) Regrowth curves of M. tuberculosis H37Rv following 2 h of exposure to isoniazid (2 mg/liter). ○, cumulative GI of residual control; ♦, cumulative GI of exposed culture. The time interval between the lines (arrows) denotes the PAE. (C) Regrowth curves of M. tuberculosis H37Rv following 2 h of exposure to moxifloxacin (2 mg/liter). ○, cumulative GI of residual control; ♦, cumulative GI of exposed culture. The time interval between the lines (arrows) denotes the PAE.

TABLE 1.

PAEs against M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) after a 2-h exposure to single drugs and combinations of drugs

| Drug(s) (concn [mg/liter]) | Drug concn/MIC | PAE (h)a | CV (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rifapentine (20) | 160 | 104.0 (88.6-121.9) | 16 |

| Rifapentine (10) | 80 | 75.3 (5.6-154.8) | 95 |

| Isoniazid (2) | 33.3 | 19.7 (6.0-23.0) | 55 |

| Moxifloxacin (2) | 8 | 0.3 (0.0-18.5) | 169 |

| Moxifloxacin (1) | 4 | 0 (0) | |

| Rifapentine (10) + isoniazid (2) | 80 + 33.3 | 136.5 (40.7-260.5) | 76 |

| Rifapentine (10) + moxifloxacin (1) | 80 + 4 | 59.0 (32.7-64.7) | 33 |

| Isoniazid (2) + moxifloxacin (1) | 33.3 + 4 | 8.3 (0-27.7) | 118 |

Values are medians, and their ranges are in brackets.

CV, coefficient of variation.

Rifapentine was found to have the longest PAE (89 to 122 h). Furthermore, the PAE at 20 mg/liter of the drug appeared longer than that at 10 mg/liter, perhaps reflecting concentration dependence. The PAEs of rifapentine at therapeutic concentrations thus appear (at least) equivalent and might even be superior to those of rifampin (6). Isoniazid only produced a detectable PAE (<24 h), which corroborated the result of our previous study (6). Moxifloxacin was found to have insignificant PAE at the concentration of 1 and 2 mg/liter. This also somewhat corroborated that found for ofloxacin (6). In combination, rifapentine and isoniazid produced the most impressive PAE (137 h), suggesting probable synergistic prolongation of PAE between the two drugs. Rifapentine plus moxifloxacin furnished a lower PAE (59 h). However, there was no statistical difference in the observed PAEs between the above two combinations, or between both combinations and rifapentine alone at 10 mg/liter (for all, P > 0.05). The combination of isoniazid and moxifloxacin gave a detectable PAE of only 8 h, which might represent that of isoniazid alone. Based on the findings for PAEs of drugs in this present study, the currently recommended once-weekly administration of rifapentine and isoniazid as continuation therapy for tuberculosis (1, 2, 23), following upon the initial phase of daily or thrice-weekly administration of rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol-streptomycin, would appear justified. Pharmacokinetically, rifapentine also advantageously enjoys a longer drug elimination half-life compared to rifampin (5). On the basis of PAE, rifapentine and moxifloxacin coadministration might also warrant further exploration as an alternative to rifapentine plus isoniazid in the continuation phase of treatment. This combination may offer a therapeutic advantage, as moxifloxacin has been found to possess sterilizing activity (15), which is lacking with isoniazid (22). Indeed, once-weekly rifapentine and moxifloxacin regimens have been demonstrated to be effective in the mouse model (18). However, moxifloxacin does not appear to be a suitable candidate for replacing rifapentine in the continuation treatment regimen of tuberculosis as suggested by our PAE findings. Although one can still conjecture that the PAE of moxifloxacin might be somewhat improved by using a higher concentration of 4 mg/liter for moxifloxacin, which is currently suggested as the Cmax for therapeutic dosing of this fluoroquinolone (4), it is doubtful that such improvement, if any, would be sufficient to alter the present conclusions materially.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benator, D., M. Bhattacharya, L. Bozeman, W. Burman, A. Cantazaro, R. Chaisson, F. Gordin, C. R. Horsburgh, J. Horton, A. Khan, C. Lahart, B. Metchock, C. Pachucki, L. Stanton, A. Vernon, M. E. Villarino, Y. C. Wang, M. Weiner, S. Weis, et al. 2002. Rifapentine and isoniazid once a week versus rifampicin and isoniazid twice a week for treatment of drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-negative patients: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 360:528-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock, N. N., T. R. Sterling, C. D. Hamilton, C. Pachucki, Y. C. Wang, D. S. Conwell, A. Mosher, M. Samuels, A. Vernon, et al. 2002. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of the tolerability of rifapentine 600, 900, and 1,200 mg plus isoniazid in the continuation phase of tuberculosis treatment. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 165:1526-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bundtzen, R. W., A. U. Gerber, D. L. Cohn, and W. A. Craig. 1981. Post-antibiotic suppression of bacterial growth. Rev. Infect. Dis. 3:28-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkhardt, O., K. Borner, H. Stass, G. Beyer, M. Allewelt, C. E. Nord, and H. Lode. 2002. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of oral moxifloxacin and clarithromycin, and concentrations in serum, saliva and faeces. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 34:898-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burman, W. J., K. Gallicano, and C. Peloquin. 2001. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the rifamycin antibacterials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 40:327-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, C. Y., C. Au-Yeang, W. W. Yew, M. Hui, and A. F. B. Cheng. 2001. Postantibiotic effects of antituberculosis agents alone and in combination. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3631-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conte, J. E., Jr., J. A. Golden, M. McQuitty, J. Kipps, E. T. Lin, and E. Zurlinden. 2000. Single-dose intrapulmonary pharmacokinetics of rifapentine in normal subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:985-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig, W. A., and S. C. Ebert. 1990. Killing and regrowth of bacteria in vitro: a review. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 74:63-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson, J. M., and D. A. Mitchison. 1968. In vitro and in vivo studies to assess the suitability of antituberculous drugs for use in intermittent chemotherapy regimens. Tubercle Suppl. 49:66-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickinson, J. M., and D. A. Mitchison. 1970. Observations in vitro on the suitability of pyrazinamide for intermittent chemotherapy of tuberculosis. Tubercle 51:389-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickinson, J. M., and D. A. Mitchison. 1970. Suitability of rifampicin for intermittent administration in the treatment of tuberculosis. Tubercle 51:82-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickinson, J. M., G. A. Ellard, and D. A. Mitchison. 1968. Suitability of isoniazid and ethambutol for intermittent administration in the treatment of tuberculosis. Tubercle 49:351-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox, W. 1981. Whither short course chemotherapy? Br. J. Dis. Chest 75:331-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuursted, K. 1997. Evaluation of the post-antibiotic effect of six anti-mycobacterial agents against Mycobacterium avium by the Bactec radiometric method. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu, Y., A. R. Coates, and D. A. Mitchison. 2003. Sterilizing activities of fluoroquinolones against rifampin-tolerant populations of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:653-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inderlied, C. B., L. S. Young, and J. K. Yamada. 1987. Determination of in vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium complex isolates to antimycobacterial agents by various methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1697-1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lettieri, J., R. Vargas, V. Agarwal, and P. Liu. 2001. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of a single oral dose of moxifloxacin 400 mg in healthy male volunteers. Clin. Pharmaokinet. 40(Suppl. 1):19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lounis, N., A. Bentoucha, C. Truffot-Pernot, B. Ji, R. J. O'Brien, A. Vernon, G. Roscigno, and J. Grosset. 2001. Effectiveness of once-weekly rifapentine and moxifloxacin regimens against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3482-3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall, J. D., S. Abdel-Rahman, K. Johnson, R. E. Kauffman, and G. L. Kearns. 1999. Rifapentine pharmacokinetics in adolescents. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:882-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peloquin, C. A. 1997. Using therapeutic drug monitoring to dose the antimycobacterial drugs. Clin. Chest Med. 18:79-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stass, H., and D. Kubitza. 2001. Effects of iron supplements on the oral bioavailability of moxifloxacin, a novel 8-methoxyfluoroquinolone in humans. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 40(Suppl. 1):57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tam, C. M., S. L. Chan, K. M. Kam, E. Sim, D. Staples, K. M. Sole, H. Al-Glusein, and D. A. Mitchison. 2000. Rifapentine and isoniazid in the continuation phase of a 6-month regimen. Interim report: no activity of isoniazid in the continuation phase. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 4:262-267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tam, C. M., S. L. Chan, K. M. Kam, R. L. Goodall, and D. A. Mitchison. 2002. Rifapentine and isoniazid in the continuation phase of a 6-month regimen. Final report at 5 years: prognostic value of various measures. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 6:3-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogelman, B. S., and W. A. Craig. 1985. Postantibiotic effects. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 15(Suppl. A):37-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]