Abstract

Complex biological systems and cellular networks may underlie most genotype to phenotype relationships. Here we review basic concepts in network biology, discussing different types of interactome networks and the insights that can come from analyzing them. We elaborate on why interactome networks are important to consider in biology, how they can be mapped and integrated with each other, what global properties are starting to emerge from interactome network models, and how these properties may relate to human disease.

Introduction

Since the advent of molecular biology, considerable progress has been made in the quest to understand the mechanisms that underlie human disease, particularly for genetically inherited disorders. Genotype-phenotype relationships, as summarized in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (Amberger et al., 2009), include mutations in more than 3,000 human genes known to be associated with one or more of over 2,000 human disorders. This is a truly astounding number of genotype-phenotype relationships considering that a mere three decades have passed since the initial description of Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLPs) as molecular markers to map genetic loci of interest (Botstein et al., 1980), only two decades since the announcement of the first positional cloning experiments of disease-associated genes using RFLPs (Amberger et al., 2009), and just one decade since the release of the first reference sequences of the human genome (Lander et al., 2001; Venter et al., 2001). For complex traits, the information gathered by recent Genome Wide Association studies suggests high-confidence genotype-phenotype associations between close to 1,000 genomic loci and one or more of over one hundred diseases, including diabetes, obesity, Crohn s disease and hypertension (Altshuler et al., 2008). The discovery of genomic variations involved in cancer, inherited in the germline or acquired somatically, is equally striking, with hundreds of human genes found linked to cancer (Stratton et al., 2009). In light of new powerful technological developments such as next-generation sequencing, it is easily imaginable that a catalog of nearly all human genomic variations, whether deleterious, advantageous, or neutral, will be available within our lifetime.

Despite the natural excitement emerging from such a huge body of information, daunting challenges remain. Practically, the genomic revolution has thus far seldom translated directly into the development of new therapeutic strategies, and the mechanisms underlying genotype-phenotype relationships remain only partially explained. Assuming that with time most human genotypic variations will be described together with phenotypic associations, there would still be major problems to fully understand and model human genetic variations and their impact on diseases.

To understand why, consider the “one-gene/one-enzyme/one-function” concept originally framed by Beadle and Tatum (Beadle and Tatum, 1941), which holds that simple, linear connections are expected between the genotype of an organism and its phenotype. But the reality is that most genotype-phenotype relationships arise from a much higher underlying complexity. Combinations of identical genotypes and nearly identical environments do not always give rise to identical phenotypes. The very coining of the words “genotype” and “phenotype” by Johannsen more than a century ago derived from observations that inbred isogenic lines of bean plants grown in well-controlled environments give rise to pods of different size (Johannsen, 1909). Identical twins, although strikingly similar, nevertheless often exhibit many differences (Raser and O'Shea, 2005). Likewise, genotypically indistinguishable bacterial or yeast cells grown side-by-side can express different subsets of transcripts and gene products at any given moment (Elowitz et al., 2002; Blake et al., 2003; Taniguchi et al., 2010). Even straightforward Mendelian traits are not immune to complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity, differences in age of onset, and modifier mutations are more frequent than generally appreciated (Perlis et al., 2010).

We argue, along with others, that the way beyond these challenges is to decipher the properties of biological systems, and in particular, those of molecular networks taking place within cells. As is becoming increasingly clear, biological systems and cellular networks are governed by specific laws and principles, the understanding of which will be essential for a deeper comprehension of biology (Nurse, 2003; Vidal, 2009).

Accordingly, our goal is to review key aspects of how complex systems operate inside cells. Particularly, we will review how by interacting with each other, genes and their products form complex networks within cells. Empirically determining and modeling cellular networks for a few model organisms and for human has provided a necessary scaffold towards understanding the functional, logical and dynamical aspects of cellular systems. Importantly, we will discuss the possibility that phenotypes result from perturbations of the properties of cellular systems and networks. The link between network properties and phenotypes, including susceptibility to human disease, appears to be at least as important as that between genotypes and phenotypes (Figure 1).

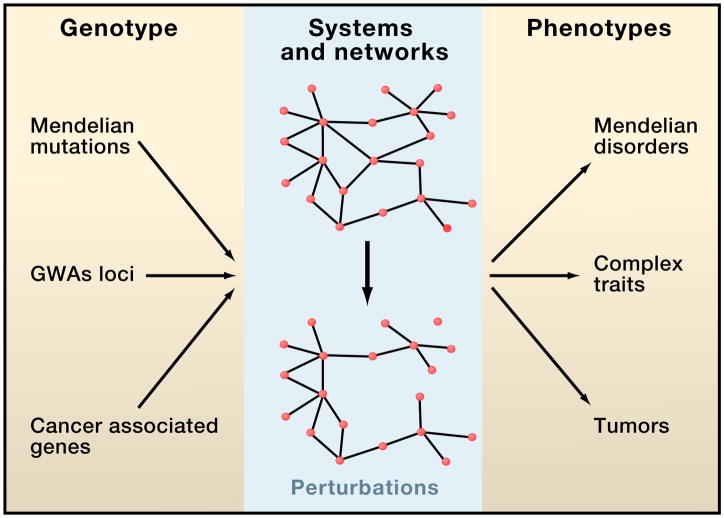

Figure 1. Perturbations in biological systems and cellular networks may underlie genotype-phenotype relationships.

By interacting with each other, genes and their products form complex cellular networks. The link between perturbations in network and systems properties and phenotypes, such as Mendelian disorders, complex traits, and cancer, might be as important as that between genotypes and phenotypes.

Cells as Interactome Networks

Systems biology can be said to have originated more than half a century ago, when a few pioneers initially formulated a theoretical framework according to which multi-scale dynamic complex systems formed by interacting macromolecules could underlie cellular behavior (Vidal, 2009). These theoretical systems biology ideas were elaborated upon at a time when there was little knowledge of the exact nature of the molecular components of biology, let alone any detailed information on functional and biophysical interactions between them. While greatly inspirational to a few specialists, systems concepts remained largely ignored by most molecular biologists, at least until empirical observations could be gathered to validate them. Meanwhile, theoretical representations of cellular organization evolved steadily, closely following the development of ever improving molecular technologies. The organizational view of the cell changed from being merely a “bag of enzymes” to a web of highly inter-related and interconnected organelles (Robinson et al., 2007). Cells can accordingly be envisioned as complex webs of macromolecular interactions, the full complement of which constitutes the “interactome” network. At the dawn of the 21st century, with most components of cellular networks having been identified, the basic ideas of systems and network biology are ready to be experimentally tested and applied to relevant biological problems.

Mapping Interactome Networks

Network science deals with complexity by “simplifying” complex systems, summarizing them merely as components (nodes) and interactions (edges) between them. In this simplified approach, the functional richness of each node is lost. Despite or even perhaps because of such simplifications, useful discoveries can be made. As regards cellular systems, the nodes are metabolites and macromolecules such as proteins, RNA molecules and gene sequences, while the edges are physical, biochemical and functional interactions that can be identified with a plethora of technologies. One challenge of network biology is to provide maps of such interactions using systematic and standardized approaches and assays that are as unbiased as possible. The resulting “interactome” networks, the networks of interactions between cellular components, can serve as scaffold information to extract global or local graph theory properties. Once shown to be statistically different from randomized networks, such properties can then be related back to a better understanding of biological processes. Potentially powerful details of each interaction in the network are left aside, including functional, dynamic and logical features, as well as biochemical and structural aspects such as protein post-translational modifications or allosteric changes. The power of the approach resides precisely in such simplification of molecular detail, which allows modeling at the scale of whole cells.

Early attempts at experimental proteome-scale interactome network mapping in the mid-1990s (Finley and Brent, 1994; Bartel et al., 1996; Fromont-Racine et al., 1997; Vidal, 1997) were inspired by several conceptual advances in biology. The biochemistry of metabolic pathways had already given rise to cellular scale representations of metabolic networks. The discovery of signaling pathways and cross-talk between them, as well as large molecular complexes such as RNA polymerases, all involving innumerable physical protein-protein interactions, suggested the existence of highly connected webs of interactions. Finally, the rapidly growing identification of many individual interactions between transcription factors and specific DNA regulatory sequences involved in the regulation of gene expression raised the question of how transcriptional regulation is globally organized within cells.

Three distinct approaches have been used since to capture interactome networks: i) compilation or curation of already existing data available in the literature, usually obtained from one or just a few types of physical or biochemical interactions (Roberts, 2006); ii) computational predictions based on available “orthogonal” information apart from physical or biochemical interactions, such as sequence similarities, gene-order conservation, co-presence and co-absence of genes in completely sequenced genomes and protein structural information (Marcotte and Date, 2001); and iii) systematic, unbiased high-throughput experimental mapping strategies applied at the scale of whole genomes or proteomes (Walhout and Vidal, 2001). These approaches, though complementary, differ greatly in the possible interpretations of the resulting maps. Literature-curated maps present the advantage of using already available information, but are limited by the inherently variable quality of the published data, the lack of systematization, and the absence of reporting of negative data (Cusick et al., 2009; Turinsky et al., 2010). Computational prediction maps are fast and efficient to implement, and usually include satisfyingly large numbers of nodes and edges, but are necessarily imperfect because they use indirect information (Plewczynski and Ginalski, 2009). While high-throughput maps attempt to describe unbiased, systematic and well-controlled data, they were initially more difficult to establish, although recent technological advances suggest that near completion can be reached within a few years for highly reliable, comprehensive protein-protein interaction and gene regulatory network maps for human (Venkatesan et al., 2009).

The mapping and analysis of interactome networks for model organisms was instrumental in getting to this point. Such efforts provided, and will continue to provide, both necessary pioneering technologies and crucial conceptual insights. As with other aspects of biology, advancements in mapping of interactome networks would have been minimal without a focus on model organisms (Davis, 2004). The field of interactome mapping has been helped by developments in several model organisms, primarily the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the fly Drosophila melanogaster, and the worm Caenorhabditis elegans (Figure 2). For instance, genome-wide resources such as collections of all, or nearly all, open reading frames (ORFeomes) were first generated for these model organisms, both because their genomes are the best annotated and because there are fewer complications, such as the high number of splice variants in human and other mammals. ORFeome resources allow efficient transfer of large numbers of ORFs into vectors suitable for diverse interactome mapping technologies (Hartley et al., 2000; Walhout et al., 2000b). Moreover, gene ablation technologies, knockouts (for yeast) and knockdowns by RNAi (for worms and flies) and transposon insertions (for plants), were discovered in and are being applied genome-wide for these model organisms (Mohr et al., 2010).

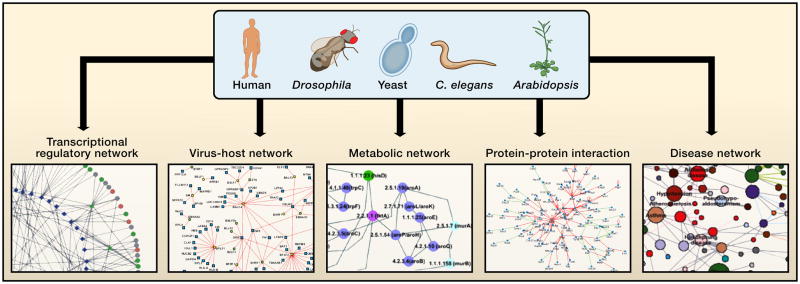

Figure 2. Networks in cellular systems.

To date cellular networks are most available for the “super-model” organisms (Davis, 2004) yeast, worm, fly, and plant. High-throughput interactome mapping relies upon genome-scale resources such as ORFeome resources, a segment of which is shown in the background. Several types of interactome networks discussed are depicted around the periphery. In a protein interaction network nodes represent proteins and edges represent physical interactions. In a transcriptional regulatory network nodes represent transcription factors (circular nodes) or putative DNA regulatory elements (diamond nodes) and edges represent physical binding between the two. In a gene-disease network, nodes represent disease genes and edges represent genes mutation of which is associated with disease. In a virus-host network nodes represent viral proteins (square nodes) or host proteins (round nodes) and edges represent physical interactions between the two. In a metabolic network nodes represent enzymes and edges represent metabolites that are products or substrates of the enzymes. The network depictions seem dense, but they represent only small portions of available interactome network maps, which themselves constitute only a few percent of the complete interactomes within cells.

Metabolic Networks

Metabolic network maps attempt to comprehensively describe all possible biochemical reactions for a particular cell or organism (Schuster et al., 2000; Edwards et al., 2001). In many representations of metabolic networks, nodes are biochemical metabolites and edges are either the reactions that convert one metabolite into another or the enzymes that catalyze these reactions (Jeong et al., 2000; Schuster et al., 2000) (Figure 2). Edges can be directed or undirected, depending on whether a given reaction is reversible or not. In specific cases of metabolic network modeling, the converse situation can be used, with nodes representing enzymes and edges pointing to “adjacent” pairs of enzymes for which the product of one is the substrate of the other (Lee et al., 2008).

Although large metabolic pathway charts have existed for decades (Kanehisa et al., 2008), nearly complete metabolic network maps required the completion of full genome sequencing together with accurate gene annotation tools (Oberhardt et al., 2009). Network construction is manual with computational assistance, involving: i) the meticulous curation of large numbers of publications, each describing experimental results regarding one or several metabolic reactions characterized from purified or reconstituted enzymes, and ii) when necessary, the compilation of predicted reactions from studies of orthologous enzymes experimentally characterized in other species. Assembly of the union of all experimentally demonstrated and predicted reactions gives rise to proteome-scale network maps (Mo and Palsson, 2009). Such maps have been compiled for numerous species, predominantly prokaryotes and unicellular eukaryotes (Oberhardt et al., 2009), and full-scale metabolic reconstructions are now underway for human as well (Ma et al., 2007). Metabolic network maps are likely the most comprehensive of all biological networks, although considerable gaps will remain to be filled in by direct experimental investigations.

Protein-Protein Interaction Networks

In protein-protein interaction network maps, nodes represent proteins and edges represent a physical interaction between two proteins. The edges are non-directed, as it cannot be said which protein binds the other, that is, which partner functionally influences the other (Figure 2). Of the many methodologies that can map protein-protein interactions, two are currently in wide use for large-scale mapping. Mapping of binary interactions is primarily carried out by ever improving variations of the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system (Fields and Song, 1989; Dreze et al., 2010). Mapping of membership in protein complexes, providing indirect associations between proteins, is carried out by affinity- or immuno- purification to isolate protein complexes, followed by some form of mass spectrometry (AP/MS) to identify protein constituents of these complexes (Rigaut et al., 1999; Charbonnier et al., 2008). While Y2H datasets contain mostly direct binary interactions, AP/MS co-complex data sets are composed of direct interactions mixed with a preponderance of indirect associations. Accordingly, the graphs generated by these two approaches exhibit different global properties (Seebacher and Gavin, 2011), such as the relationships between gene essentiality and the number of interacting proteins (Yu et al., 2008).

In the past decade significant steps have been taken towards the generation of comprehensive protein-protein interaction network maps. Comprehensive efforts using Y2H technologies to generate interactome maps began with the model organisms S. cerevisiae, C. elegans and D. melanogaster (Ito et al., 2000; Uetz et al., 2000; Walhout et al., 2000a; Ito et al., 2001; Giot et al., 2003; Reboul et al., 2003; Li et al., 2004), and eventually included human (Colland et al., 2004; Rual et al., 2005; Stelzl et al., 2005; Venkatesan et al., 2009). Comprehensive mapping of co-complex membership by high-throughput AP/MS was initially undertaken in yeast (Gavin et al., 2002; Ho et al., 2002), rapidly progressing to ever improving completeness and quality thereafter (Gavin et al., 2006; Krogan et al., 2006). For technical reasons future comprehensive AP/MS efforts will stay focused on unicellular organisms such as yeast (Collins et al., 2007) and mycoplasma (Kuhner et al., 2009), whereas Y2H efforts are more readily implemented for complex multicellular organisms (Seebacher and Gavin, 2011).

In their early implementations, systematic and comprehensive interaction network mapping efforts met with skepticism regarding their accuracy (von Mering et al., 2002), analogous to the original concerns over whether automated high-throughput genome sequencing efforts might have considerably lower accuracy than dedicated efforts carried out cumulatively in many laboratories. Only after the emergence of rigorous statistical tests to estimate sequencing accuracy could high-throughput sequencing efforts reach their full potential (Ewing et al., 1998). Analogously, an empirical framework recently propagated for protein interaction mapping (Venkatesan et al., 2009) now allows the estimation of overall accuracy and sensitivity for maps obtained using high-throughput mapping approaches.

Four critical parameters need to be estimated: completeness (the number of physical protein pairs actually tested in a given search space); assay sensitivity (which interactions can and cannot be detected by a particular assay); sampling sensitivity (the fraction of all detectable interactions found by a single implementation of any interaction assay); and precision (the proportion of true biophysical interactors). Careful consideration of these parameters offers a quantitative idea of the completeness and accuracy of a particular high-throughput interaction map (Yu et al., 2008; Simonis et al., 2009; Venkatesan et al., 2009), and allows comparison of multiple maps as long as standardized framework parameters are used. In contrast, comparing the results of small-scale experiments available in literature curated databases is not possible, as there is simply no way to control for accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity. The binary interactome empirical framework offers a way to estimate the size of interactome networks, which in turn is essential to define a roadmap to reach completion for the interactome mapping efforts of any species of interest. While originally established for protein-protein interaction mapping, similar empirical frameworks can be applied more broadly to mapping of other types of interactome networks (Costanzo et al., 2010).

Gene Regulatory Networks

In most gene regulatory network maps, nodes are either a transcription factor or a putative DNA regulatory element, and directed edges represent the physical binding of transcription factors to such regulatory elements. Edges can be said to be incoming (transcription factor binds a regulatory DNA element) or outgoing (regulatory DNA element bound by a transcription factor) (Figure 2). Currently, two general approaches are amenable to large-scale mapping of gene regulatory networks. In yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) approaches, a putative cis-regulatory DNA sequence, commonly a suspected promoter region, is used as bait to capture transcription factors that bind to that sequence (Deplancke et al., 2004). In chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) approaches, antibodies raised against transcription factors of interest, or against a peptide tag used in fusion with potential transcription factors, are used to immunoprecipitate potentially interacting cross-linked DNA fragments (Lee et al., 2002). As Y1H proceeds from genes and captures associated proteins it is said to be “gene-centric”, whereas ChIP strategies are “protein-centric” in that they proceed from transcription factors and attempt to capture associated gene regions (Walhout, 2006). The two approaches are complementary. The Y1H system can discover novel transcription factors but relies on having known, or at least suspected, regulatory regions; ChIP methods can discover novel regulatory motifs but rely on the availability of reagents specific to transcription factors of interest, which themselves depend on accurate predictions of transcription factors (Reece-Hoyes et al., 2005; Vaquerizas et al., 2009)

Large-scale Y1H networks have been produced for C. elegans (Vermeirssen et al., 2007; Grove et al., 2009). Large-scale ChIP-based networks have been produced for yeast (Lee et al., 2002) and have been carried out for mammalian tissue culture cells as well (Cawley et al., 2004).

In addition to transcription factor activities, overall gene transcript levels are also regulated post-transcriptionally by micro RNAs (miRNAs), short non-coding RNAs that bind to complementary cis-regulatory RNA sequences usually located in 3 untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs (Lee et al., 2004; Ruvkun et al., 2004). miRNAs are not expected to act as master regulators, but rather act post-transcriptionally to fine-tune gene expression by modulating the levels of target mRNAs. Complex networks are formed by miRNAs interacting with their targets. In such networks, nodes are either a miRNA or a target 3 UTR, and edges represent the complementary annealing of the miRNA to the target RNA. Edges can be said to be incoming (miRNA binds a 3 UTR element) or outgoing (3 UTR element bound by a miRNA) (Martinez et al., 2008). The targets of miRNAs are generally computationally predicted, as experimental methodologies to map miRNA/3 UTR interactions at high-throughput are just coming online (Karginov et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2010; Hafner et al., 2010). Since transcription factors regulate the expression of miRNAs, it is however possible to combine Y1H methods with computationally predicted miRNA/3 UTR interactions, a strategy which was used to derive a large-scale miRNA network in C. elegans (Martinez et al., 2008) and which could be extended to other genomes.

Integrating Interactome Networks with other Cellular Networks

The three interactome network types considered so far, metabolic, protein-protein interaction and gene regulatory networks, are composed of physical or biochemical interactions between macromolecules. The corresponding network maps provide crucial “scaffold” information about cellular systems, on top of which additional layers of functional links can be added to fine-tune the representation of biological reality (Figure 3) (Vidal, 2001). Networks composed of functional links, although strikingly different in terms of what the edges represent, can nevertheless complement what can be learned from interactome network maps in powerful ways, and vice versa. Networks of functional links represent a category of cellular networks that can be derived from indirect, or “conceptual”, interactions where links between genes and gene products are reported based upon functional relationships or similarities, independently of physical macromolecular interactions. We consider three types of functional networks that have been mapped thus far at the scale of whole genomes and used together with physical interactome networks to interrogate the complexities of genotype-to-phenotype relationships.

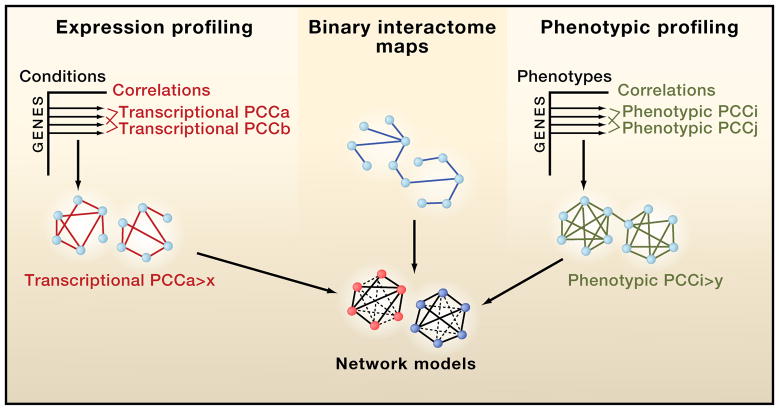

Figure 3. Integrated networks.

Co-expression and phenotypic profiling can be thought of as matrices comprising all genes of an organism against all conditions that this organism has been exposed to within a given expression compendium and all phenotypes tested, respectively. For any correlation measurement, Pearson Correlation Coefficients (PCCs) being one of the most widely used, the threshold between what is considered co-expressed and non-co-expressed needs to be set using appropriate titration procedures. The resulting integrated networks have powerful predictive value.

Transcriptional Profiling Networks

Gene products that function together in common signaling cascades or protein complexes are expected to show greater similarities in their expression patterns than random sets of gene products. But how does this expectation translate at the level of whole proteomes and transcriptomes? How do transcriptome states correlate globally with interactome networks? Since the original description of microarray and DNA chip techniques and more recently de novo RNA sequencing using next-generation sequencing technologies, vast compendiums of gene expression datasets have been generated for many different species across a multitude of diverse genetic and environmental conditions. This type of information can be thought of as matrices comprising all genes of an organism against all conditions that this organism has been exposed to within a given expression compendium (Vidal, 2001). In the resulting co-expression networks, nodes represent genes, and edges link pairs of genes that show correlated co-expression above a set threshold (Kim et al., 2001; Stuart et al., 2003). For any correlation measurement, Pearson Correlation Coefficients (PCCs) being commonly used, the threshold between what is considered co-expressed and not co-expressed needs to be set using appropriate titration procedures (Stuart et al., 2003; Gunsalus et al., 2005).

Integration attempts in yeast, combining physical protein-protein interaction maps with co-expression profiles, revealed that interacting proteins are more likely to be encoded by genes with similar expression profiles than non-interacting proteins (Ge et al., 2001; Grigoriev, 2001; Jansen et al., 2002; Kemmeren et al., 2002). These observations were subsequently confirmed in many other organisms (Ge et al., 2003). Beyond the fundamental aspect of finding significant overlaps between interaction edges in interactome networks and co-expression edges in transcription profiling networks, these observations have been used to estimate the overall biological significance of interactome datasets. While correlations can be statistically significant over huge datasets, still many valid biologically relevant protein-protein interactions correspond to pairs of genes whose expression is uncorrelated or even anti-correlated. Co-expression similarity links need not be perfectly overlapping with physical interactions of the corresponding gene products and vice versa.

In another example of what co-expression networks can be used for, preliminary steps have been taken to delineate gene regulatory networks from co-expression profiles (Segal et al., 2003; Amit et al., 2009). Such network constructions provide verifiable hypotheses about how regulatory pathways operate.

Phenotypic Profiling Networks

Perturbations of genes that encode functionally related products often confer similar phenotypes. Systematic use of gene knock-out strategies developed for yeast (Giaever et al., 2002) and knock-down approaches using RNA interference (RNAi) for C. elegans, Drosophila and recently human (Mohr et al., 2010), are amenable to the perturbation of (nearly) all genes and subsequent testing of a wide variety of standardized phenotypes. As with transcriptional profiling networks, this type of information can be thought of as matrices comprising all genes of an organism and all phenotypes tested within a given phenotypic profiling compendium. In the resulting phenotypic similarity or “phenome” network, nodes represent genes, and edges link pairs of genes that show correlated phenotypic profiles above a set threshold. Here again, titration is needed to decide on the threshold between what is considered phenotypically similar and what is not (Gunsalus et al., 2005).

The earliest evidence that phenotypic profiling or “phenome” networks might help in interpreting protein-protein interactome networks was obtained in studies of the C. elegans DNA damage response and hermaphrodite germline (Boulton et al., 2002; Piano et al., 2002; Walhout et al., 2002). The physical basis of phenome networks is not yet completely defined, though there are strong overlaps between correlated phenotypic profiles and physical protein-protein interactions (Walhout et al., 2002; Gunsalus et al., 2005). Overlapping three network types, binary interactions, co-expression, and phenotype profiling, produce integrated networks with high predictive power, as demonstrated for C. elegans early embryogenesis (Walhout et al., 2002; Gunsalus et al., 2005). Integration of transcriptional regulatory networks with these other network types has also been undertaken in worm (Grove et al., 2009).

Comprehensive genome-wide phenome networks are now a reality for the yeast S. cerevisiae (Giaever et al., 2002), and are expected to be further developed for C. elegans (Sönnichsen et al., 2005) and Drosophila (Mohr et al., 2010). Now that RNAi reagents are available for nearly all genes of mouse and human (Root et al., 2006), phenome maps for cell lines of these organisms should soon follow.

Genetic Interaction Networks

Pairs of functionally related genes tend to exhibit genetic interactions, defined by comparing the phenotype conferred by mutations in pairs of genes (double mutants) to the phenotype conferred by either one of these mutations alone (single mutants). Genetic interactions are classified as negative, i.e. aggravating, synthetic sick or lethal, when the phenotype of double mutants is significantly worse than expected from that of single mutants, and positive, i.e. alleviating or suppressive, when the phenotype of double mutants is significantly better than that expected from the single mutants (Mani et al., 2008). Though finding genetic interactions has been crucial to geneticists for decades (Sturtevant, 1956; Novick et al., 1989), only in the last ten years has functional genomics advanced sufficiently to allow systematic high-throughput mapping of genetic interactions to give rise to large-scale networks (Boone et al., 2007).

Two general strategies have been followed for the systematic mapping of genetic interactions in yeast. Synthetic genetic arrays (SGA) and derivative methodologies use high-density arrays of double mutants by mating pairs from an available set of single mutants (Tong et al., 2001; Boone et al., 2007). Alternative strategies take advantage of sequence barcodes embedded in a set of yeast deletion mutants (Giaever et al., 2002; Beltrao et al., 2010) to measure the relative growth rate in a population of double mutants by hybridization to anti-barcode microarrays (Pan et al., 2004; Boone et al., 2007). These two approaches seem to capture similar aspects of genetic interactions, as the overlap between the two types of datasets is significant (Costanzo et al., 2010).

Patterns of genetic interactions can be used to define a kind of network that is similar to phenotypic profiling or phenome networks. As with transcriptional and phenotypic profiling networks, this type of information can be thought of as matrices comprising all genes of an organism and the genes with which they exhibit a genetic interaction. In such “genetic interaction profiling” networks, edges functionally link two genes based on high similarities of genetic interaction profiles. Here again, predictive models of biological processes can be obtained when such networks are combined with other types of interactome networks.

Integration of genetic interaction networks with other types of interactome network maps provides potentially powerful models. While genetic interactions do not necessarily correspond to physical interactions between the corresponding gene products (Mani et al., 2008), interesting patterns emerge between the different datasets. Because they tend to reveal pairs of genes involved in parallel pathways or in different molecular machines, negative genetic interactions tend not to correlate with either protein associations in protein complexes or with binary protein-protein interactions (Beltrao et al., 2010; Costanzo et al., 2010). In contrast, positive genetic interactions tend to point to pairs of gene products physically associated with each other. This trend is usually explained by loss of either one or two gene products working together in a molecular complex resulting in similar effects (Beltrao et al., 2010).

Graph Properties of Networks

A critical realization over the past decade is that the structure and evolution of networks appearing in natural, technological, and social systems over time follows a series of basic and reproducible organizing principles. Theoretical advances in network science (Albert and Barabasi, 2002), paralleling advances in high-throughput efforts to map biological networks, have provided a conceptual framework with which to interpret large interactome network maps. Full understanding of the internal organization of a cell requires awareness of the constraints and laws that biological networks follow. We summarize several principles of network theory that have immediate applications to biology.

Degree Distribution and Hubs

Any empirical investigation starts with the same question: could the investigated phenomena have emerged by chance, or could random effects account for them? The earliest network models assumed that complex networks are wired randomly, such that any two nodes are connected by a link with the same probability p. This Erdos-Renyi model generates a network with a Poisson degree distribution, which implies that most nodes have approximately the same degree, that is, the same number of links, while nodes that have significantly more or fewer links than any average node are exceedingly rare or altogether absent. In contrast, many real networks, from the World Wide Web to social networks, are scale-free (Barabási and Albert, 1999), which means that their degree distribution follows a power law rather than the expected Poisson distribution. In a scale-free network most nodes have only a few interactions, and these coexist with a few highly connected nodes, the hubs, that hold the whole network together. This scale-free property has been found in all organisms for which protein-protein interaction and metabolic network maps exist, from yeast to humans (Barabási and Oltvai, 2004; Seebacher and Gavin, 2011). Regulatory networks, however, show a mixed behavior. The outgoing degree distribution, corresponding to how many different genes a transcription factor can regulate, is scale-free, meaning that some master regulators can regulate hundreds of genes. In contrast, the incoming degree distribution, corresponding to how many transcription factors regulate a specific gene, best fits an exponential model (Deplancke et al., 2006), indicating that genes that are simultaneously regulated by large numbers of transcription factors are exponentially rare.

Gene Duplication as the Origin of the Scale-Free Property

The scale-free topology of biological networks likely originates from gene duplication. While the principle applies from metabolic to regulatory networks, it is best illustrated in protein-protein interaction networks, where it was first proposed (Pastor-Satorras et al., 2003; Vázquez et al., 2003). When cells divide and the genome replicates, occasionally an extra copy of one or several genes or chromosomes gets produced. Immediately following a duplication event, both the original protein and the new extra copy have the same structure, so both interact with the same set of partners. Consequently, each of the protein partners that interacted with the ancestor gains a new interaction. This process results in a rich-get-richer phenomenon (Barabási and Albert, 1999), where proteins with a large number of interactions tend to gain links more often, as it is more likely that they interact with a duplicated protein. This mechanism has been shown to generate hubs (Pastor-Satorras et al., 2003; Vázquez et al., 2003), and so could be responsible for the scale-free property of protein-protein interaction networks.

The Role of Hubs

Network biology attempts to identify global properties in interactome network graphs, and subsequently relate such properties to biological reality by integrating various functional datasets. One of the best examples where this approach was successful is in defining the role of hubs. In the model organisms S. cerevisiae and C. elegans, hub proteins were found to: i) correspond to essential genes (Jeong et al., 2001), ii) be older and have evolved more slowly (Fraser et al., 2002), iii) have a tendency to be more abundant (Ivanic et al., 2009), and iv) have a larger diversity of phenotypic outcomes resulting from their deletion compared to the deletion of less connected proteins (Yu et al., 2008). While the evidence attributed to some of these findings has been debated (Jordan et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2008; Ivanic et al., 2009), the special role of hub proteins in model organisms led to the expectation that, in humans, hubs should preferentially encode disease-related genes. Indeed, up-regulated genes in lung squamous cell carcinoma tissues tend to have a high degree in protein-protein interaction networks (Wachi et al., 2005), and cancer-related proteins have, on average, twice as many interaction partners as non-cancer proteins in protein-protein interaction networks (Jonsson and Bates, 2006). A cautionary note is necessary: since disease-related proteins tend to be more avidly studied their higher connectivity may be partly rooted in investigative biases. Therefore this type of finding needs to be appropriately controlled using systematic proteome-wide interactome network maps.

Understanding the role of hubs in human disease requires distinguishing between essential genes and disease-related genes (Goh et al., 2007). Some human genes are essential for early development, such that mutations in them often lead to spontaneous abortions. The protein products of mouse in utero essential genes show a strong tendency to be associated with hubs and to be expressed in multiple tissues (Goh et al., 2007). Non-essential disease genes tend not to be encoded by hubs and tend to be tissue specific. These differences can be best appreciated from an evolutionary perspective. Mutations that disrupt hubs may have difficulty propagating in the population, as the host may not survive long enough to have offspring. Only mutations that impair functionally and topologically peripheral genes can persist, becoming responsible for heritable diseases, particularly those that manifest in adulthood.

Date and Party Hubs

Another success in uncovering the functional consequences of the topology of interactome networks was provided by the discovery of date and party hubs (Han et al., 2004). Upon integrating protein-protein interaction network data with transcriptional profiling networks for yeast, at least two classes of hubs can be discriminated. Party hubs are highly co-expressed with their interacting partners while date hubs appear to be more dynamically regulated relative to their partners (Han et al., 2004). In other words, date hubs interact with their partners at different times and/or different conditions, whereas party hubs seem to interact with their partners at all times or conditions tested (Seebacher and Gavin, 2011). Despite the preponderance of evidence in its favor, the date and party hubs concept remains a subject of debate, (Agarwal et al., 2010), attributable to the necessity to appropriately calibrate co-expression and protein-protein interaction hub thresholds when analyzing new transcriptome and interactome datasets (Bertin et al., 2007).

Fundamentally, date hubs preferentially connect functional modules to each other, whereas party hubs preferentially act inside functional modules, hence they are occasionally called inter-module and intra-module hubs, respectively (Han et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2009). Date hubs are less evolutionarily constrained than party hubs (Fraser, 2005; Ekman et al., 2006; Bertin et al., 2007). Party hubs contain fewer and shorter regions of intrinsic disorder than do date hubs (Ekman et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2006; Kahali et al., 2009) and contain fewer linear motifs (short binding motifs and post-translational modification sites) than do date hubs (Taylor et al., 2009). Initially explored in a yeast interactome (Han et al., 2004; Ekman et al., 2006), the distinction between date and party hubs can be recapitulated in human interactomes as well (Taylor et al., 2009).

Motifs

There has been considerable attention paid in recent years to network motifs, which are characteristic network patterns, or subgraphs, in biological networks that appear more frequently than expected given the degree distribution of the network (Milo et al., 2002). Such subgraphs have been found to be associated with desirable (or undesirable) biological function (or dysfunction). Hence identification and classification of motifs can offer information about the various network subgraphs needed for biological processes. It is now commonly understood that motifs constitute the basic building blocks of cellular networks (Milo et al., 2002; Yeger-Lotem et al., 2004).

Originally identified in transcriptional regulatory networks of several model organisms (Milo et al., 2002; Shen-Orr et al., 2002), motifs have been subsequently identified in interactome networks and in integrated composite networks (Yeger-Lotem et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). Different types of networks exhibit different motif profiles, suggesting a means for network classification (Milo et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2005). The high degree of evolutionary conservation of motif constituents within interaction networks (Wuchty et al., 2003), combined with the convergent evolution that is seen in the transcription regulatory networks of diverse species towards the same motif types (Barabási and Oltvai, 2004), makes a strong argument that motifs are of direct biological relevance. Classification of several highly significant motifs of two, three, and four nodes, with descriptors like coherent feed forward loop or single-input module, has shown that specific types of motifs carry out specific dynamic functions within cells (Alon, 2007; Shoval and Alon, 2010).

Topological, functional and disease modules

Most biological networks have a rather uneven organization. Many nodes are part of locally dense neighborhoods, or topological modules, where nodes have a higher tendency to link to nodes within the same local neighborhood than to nodes outside of it (Ravasz et al., 2002). A region of the global network diagram that corresponds to a potential topological module can be identified by network clustering algorithms which are blind to the function of individual nodes. These topological modules are often believed to carry specific cellular functions, hence leading to the concept of a functional module, an aggregation of nodes of similar or related function in the same network neighborhood. Interest is increasing in disease modules, which represent groups of network components whose disruption results in a particular disease phenotype in humans (Barabási et al., 2010).

There is a tacit assumption, based on evidence in the biological literature, that cellular components forming topological modules have closely related functions, thus corresponding to functional modules. New potentially powerful methods to identify topological and functional clusterings continue to be described (Ahn et al., 2010). Such modules can serve as hypothesis building tools to identify “regions” of the interactome likely involved in particular cellular functions or disease (Barabási et al., 2010).

Networks and Human Diseases

Having reviewed why biological networks are important to consider, how they can be mapped and integrated with each other, and what global properties are starting to emerge from such models, we next return to our original question: to what extent do biological systems and cellular networks underlie genotype-phenotype relationships in human disease? We attempt to provide answers by covering four recent advancements in network biology: i) studies of global relationships between human disorders, associated genes and interactome networks, ii) predictions of new human disease-associated genes using interactome models, iii) analyses of network perturbations by pathogens, and iv) emergence of node removal versus edge-specific or “edgetic” models to explain genotype-phenotype relationships.

Global Disease Networks

One of the main predictions derived from the hypothesis that human disorders should be viewed as perturbations of highly interlinked cellular networks is that diseases should not be independent from each other, but should instead be themselves highly interconnected. Such potential cellular network-based dependencies between human diseases has led to the generation of various global disease network maps, which link disease phenotypes together if some molecular or phenotypic relationships exist between them. Such a map was built using known gene-disease associations collected in the OMIM database (Goh et al., 2007), where nodes are diseases and two diseases are linked by an edge if they share at least one common gene, mutations in which are associated with these diseases. In the obtained disease network more than 500 human genetic disorders belong to a single interconnected main giant component, consistent with the idea that human diseases are much more connected to each other than anticipated. The flip side of this representation of connectivity is a network of disease-associated genes linked together if mutations in these genes are known to be responsible for at least one common disorder. Providing support for our general hypothesis that perturbations in cellular networks underlie genotype-phenotype relationships, such disease associated gene networks overlap significantly with human protein-protein interactome network maps (Goh et al., 2007).

Additional types of connectivity between large numbers of human diseases can be found in “co-morbidity” networks where diseases are linked to each other when individuals who were diagnosed for one particular disease are more likely to have also been diagnosed for the other (Rzhetsky et al., 2007; Hidalgo et al., 2009). Diabetes and obesity represent probably the best known disease pair with such significant co-morbidity. While co-morbidity can have multiple origins, ranging from environmental factors to treatment side effects, its potential molecular origin has attracted considerable attention. A network biology interpretation would suggest that the molecular defects responsible for one of a pair of diseases can “spread along” the edges in cellular networks, affecting the activity of related gene products and causing or affecting the outcome of the other disease (Park et al., 2009).

Predicting Disease Related genes using Interactome Networks

If cellular networks underlie genotype-phenotype relationships, then network properties should be predictive of novel, yet to be identified human disease-associated genes. In an early example, it was shown that the products of a few dozen ataxia-associated genes occupy distinct “locations” in the human interactome network, in that the number of edges separating them is on average much lower than for random sets of gene products (Lim et al., 2006). Physical protein-protein interactome network maps can indeed generate lists of genes potentially enriched for new candidate disease genes or modifier genes of known disease genes (Lim et al., 2006; Oti et al., 2006; Fraser and Plotkin, 2007).

Integration of various interactome and functional relationship networks have also been applied to reveal genes potentially involved in cancer (Pujana et al., 2007). Integrating a co-expression network, seeded with four well-known breast cancer associated genes, together with genetic and physical interactions yielded a breast cancer network model out of which candidate cancer susceptibility and modifier genes could be predicted (Pujana et al., 2007). Integrative network modeling strategies are applicable to other types of cancer and other types of disease (Ergun et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010).

Network Perturbations by Pathogens

Pathogens, particularly viruses, have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to perturb the intracellular networks of their hosts to their advantage. As obligate intracellular pathogens, viruses must intimately rewire cellular pathways to their own ends to maintain infectivity. Since many virus-host interactions happen at the level of physical protein-protein interactions, systematic maps capturing viral-host physical protein-protein interactions, or “virhostome” maps, have been obtained using Y2H for Epstein-Barr virus (Calderwood et al., 2007), hepatitis C virus (de Chassey et al., 2008), several herpesviruses (Uetz et al., 2006), influenza virus (Shapira et al., 2009) and others (Mendez-Rios and Uetz, 2010), and by co-AP/MS methodologies for HIV (Jäger et al., 2010). An eminent goal is to find perturbations in network properties of the host network, properties that would not be made evident by small-scale investigations focused on one or a handful of viral proteins. For instance, it has been found several times now that viral proteins preferentially target hubs in host interactome networks (Calderwood et al., 2007; Shapira et al., 2009). The many host targets identified in virhostome screens are now getting biologically validated by RNAi knock-down and transcriptional profiling, leading to detailed maps of the interactions underlying viral-host relationships (Shapira et al., 2009).

Another impetus for mapping virhostome networks is that virus protein interactions can act as surrogates for human genetic variations, inducing disease states by influencing local and global properties of cellular networks. The inspiration for this concept emerged from classical observations such as the binding of Adenovirus E1A, HPV E7, and SV40 Large T antigen to the human retinoblastoma protein, which is the product of a gene in which mutations lead to a predisposition to retinoblastoma and other types of cancers (DeCaprio, 2009). This hypothesis will soon be tested globally by systematic investigations of how host networks, including physical interaction, gene regulatory and genetic interaction networks, are perturbed upon viral infection. Pathogen-host interaction mapping projects are also in their first iterations, with similar goals of identifying emergent global properties and disease surrogates. As microbial pathogens can have thousands of gene products relative to much smaller numbers for most viruses, such projects will require considerably more effort and time.

Edgetics

Our underlying premise throughout has been that phenotypic variations of an organism, particularly those that result in human disease, arise from perturbations of cellular interactome networks. These alterations range from the complete loss of a gene product, through the loss of some but not all interactions, to the specific perturbation of a single molecular interaction while retaining all others. In interactome networks these alterations range from node removal at one end and edge-specific or “edgetic” perturbations at the other (Zhong et al., 2009). The consequences on network structure and function are expected to be radically dissimilar for node removal versus edgetic perturbation. Node removal not only disables the function of a node but also disables all the interactions of that node with other nodes, disrupting in some way the function of all of the neighboring nodes. An edgetic disruption, removing one or a few interactions but leaving the rest intact and functioning, has subtler effects on the network, though not necessarily on the resulting phenotype (Madhani et al., 1997). The distinction between node removal and edgetic perturbation models can provide new clues on mechanisms underlying human disease, such as the different classes of mutations that lead to dominant versus recessive modes of inheritance (Zhong et al., 2009).

The idea that the disruption of specific protein interactions can lead to human disease (Schuster-Bockler and Bateman, 2008) complements canonical gene loss/perturbation models (Botstein and Risch, 2003), and is poised to explain confounding genetic phenomena such as genetic heterogeneity.

Matching the edgetic hypothesis to inherited human diseases, approximately half of ~50,000 Mendelian alleles available in the Human Gene Mutation Database can be modeled as potentially edgetic if one considers deletions and truncating mutations as node removal, and in-frame point mutations leading to single amino-acid changes and small insertions and deletions as edgetic perturbations (Zhong et al., 2009). This number is probably a good approximation, since thus far disease-associated genes predicted to bear edgetic alleles using this model have been experimentally confirmed (Zhong et al., 2009). Consistent with the edgetic hypothesis, for genes associated with multiple disorders and for which predicted protein interaction domains are available, it was shown that putative edgetic alleles responsible for different disorders tend to be located in different interaction domains, consistent with different edgetic perturbations conferring strikingly different phenotypes.

Conclusion

A comprehensive catalog of sequence variations among the ~7 billion human genomes present on earth might soon become available. This information is and will continue to revolutionize biology in general and medicine in particular for many decades and perhaps centuries to come. The prospects of predictive and personalized medicine are enormous. However, it should be kept in mind that genome variations merely constitute variations in the “parts list”, and often fail to provide a description of the mechanistic consequences on cellular functions.

Here we have summarized why considering perturbations of biological networks within cells is crucial to help interpret how genome variations relate to phenotypic differences. Given their high levels of complexity, it is no surprise that interactome networks have not yet been mapped completely. The data and models accumulated in the last decade point to clear directions for the next decade. We envision that with more interactome datasets of increasingly high quality, the trends reviewed here will be fine-tuned. The global properties observed so far and those yet to be uncovered will “make sense” of the enormous body of information encompassed in the human genome.

Acknowledgments

We thank David E. Hill, Matija Dreze, Anne-Ruxandra Carvunis, Benoit Charloteaux, Quan Zhong, Balaji Santhanam, Sam Pevzner, Song Yi, Nidhi Sahni, Jean Vandenhaute and Roseann Vidal for careful reading of the manuscript. Interactome mapping efforts at CCSB have been supported mainly by National Institutes of Health grant R01-HG001715. M.V. is grateful to Nadia Rosenthal for the peaceful Suttonian environment. We apologize to those in the field whose important work was not cited here due to space limitation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agarwal S, Deane CM, Porter MA, Jones NS. Revisiting date and party hubs: novel approaches to role assignment in protein interaction networks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6:e1000817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn YY, Bagrow JP, Lehmann S. Link communities reveal multiscale complexity in networks. Nature. 2010;466:761–764. doi: 10.1038/nature09182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert R, Barabasi AL. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Rev Mod Physics. 2002;74:47–97. [Google Scholar]

- Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Lander ES. Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 2008;322:881–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1156409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberger J, Bocchini CA, Scott AF, Hamosh A. McKusick's Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D793–796. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit I, Garber M, Chevrier N, Leite AP, Donner Y, Eisenhaure T, Guttman M, Grenier JK, Li W, Zuk O, et al. Unbiased reconstruction of a mammalian transcriptional network mediating pathogen responses. Science. 2009;326:257–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1179050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;12:56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási AL, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel PL, Roecklein JA, SenGupta D, Fields S. A protein linkage map of Escherichia coli bacteriophage T7. Nat Genet. 1996;12:72–77. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle GW, Tatum EL. Genetic control of biochemical reactions in Neurospora. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1941;27:499–506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.27.11.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrao P, Cagney G, Krogan NJ. Quantitative genetic interactions reveal biological modularity. Cell. 2010;141:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin N, Simonis N, Dupuy D, Cusick ME, Han JD, Fraser HB, Roth FP, Vidal M. Confirmation of organized modularity in the yeast interactome. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake WJ, MKA, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature. 2003;422:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature01546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone C, Bussey H, Andrews BJ. Exploring genetic interactions and networks with yeast. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:437–449. doi: 10.1038/nrg2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botstein D, Risch N. Discovering genotypes underlying human phenotypes: past successes for mendelian disease, future approaches for complex disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33(Suppl):228–237. doi: 10.1038/ng1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick M, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 1980;32:314–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton SJ, Gartner A, Reboul J, Vaglio P, Dyson N, Hill DE, Vidal M. Combined functional genomic maps of the C. elegans DNA damage response. Science. 2002;295:127–131. doi: 10.1126/science.1065986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood MA, Venkatesan K, Xing L, Chase MR, Vazquez A, Holthaus AM, Ewence AE, Li N, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Hill DE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702332104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley S, Bekiranov S, Ng HH, Kapranov P, Sekinger EA, Kampa D, Piccolboni A, Sementchenko V, Cheng J, Williams AJ, et al. Unbiased mapping of transcription factor binding sites along human chromosomes 21 and 22 points to widespread regulation of noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2004;116:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnier S, Gallego O, Gavin AC. The social network of a cell: recent advances in interactome mapping. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 2008;14:1–28. doi: 10.1016/S1387-2656(08)00001-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colland F, Jacq X, Trouplin V, Mougin C, Groizeleau C, Hamburger A, Meil A, Wojcik J, Legrain P, Gauthier JM. Functional proteomics mapping of a human signaling pathway. Genome Res. 2004;14:1324–1332. doi: 10.1101/gr.2334104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SR, Kemmeren P, Zhao XC, Greenblatt JF, Spencer F, Holstege FC, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ. Towards a comprehensive atlas of the physical interactome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:439–450. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600381-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, Ding H, Koh JL, Toufighi K, Mostafavi S, et al. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick ME, Yu H, Smolyar A, Venkatesan K, Carvunis AR, Simonis N, Rual JF, Borick H, Braun P, Dreze M, et al. Literature-curated protein interaction datasets. Nat Methods. 2009;6:39–46. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RH. The age of model organisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:69–76. doi: 10.1038/nrg1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Chassey B, Navratil V, Tafforeau L, Hiet MS, Aublin-Gex A, Agaugue S, Meiffren G, Pradezynski F, Faria BF, Chantier T, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:230. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCaprio JA. How the Rb tumor suppressor structure and function was revealed by the study of Adenovirus and SV40. Virology. 2009;384:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplancke B, Dupuy D, Vidal M, Walhout AJ. A Gateway-compatible yeast one-hybrid system. Genome Res. 2004;14:2093–2101. doi: 10.1101/gr.2445504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deplancke B, Mukhopadhyay A, Ao W, Elewa AM, Grove CA, Martinez NJ, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Reece-Hoyes JS, Hope IA, et al. A gene-centered C. elegans protein-DNA interaction network. Cell. 2006;125:1193–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreze M, Monachello D, Lurin C, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Vidal M, Braun P. High-quality binary interactome mapping. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:281–315. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JS, Ibarra RU, Palsson BO. In silico predictions of Escherichia coli metabolic capabilities are consistent with experimental data. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:125–130. doi: 10.1038/84379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman D, Light S, Bjorklund AK, Elofsson A. What properties characterize the hub proteins of the protein-protein interaction network of Saccharomyces cerevisiae? Genome Biol. 2006;7:R45. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-6-r45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 2002;297:1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergun A, Lawrence CA, Kohanski MA, Brennan TA, Collins JJ. A network biology approach to prostate cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:82. doi: 10.1038/msb4100125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S, Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245–246. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finley RL, Jr, Brent R. Interaction mating reveals binary and ternary connections between Drosophila cell cycle regulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12980–12984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser HB. Modularity and evolutionary constraint on proteins. Nat Genet. 2005;37:351–352. doi: 10.1038/ng1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser HB, Hirsh AE, Steinmetz LM, Scharfe C, Feldman MW. Evolutionary rate in the protein interaction network. Science. 2002;296:750–752. doi: 10.1126/science.1068696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser HB, Plotkin JB. Using protein complexes to predict phenotypic effects of gene mutation. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R252. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont-Racine M, Rain JC, Legrain P. Toward a functional analysis of the yeast genome through exhaustive two-hybrid screens. Nat Genet. 1997;16:277–282. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AC, Aloy P, Grandi P, Krause R, Boesche M, Marzioch M, Rau C, Jensen LJ, Bastuck S, Dumpelfeld B, et al. Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature. 2006;440:631–636. doi: 10.1038/nature04532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AC, Bosche M, Krause R, Grandi P, Marzioch M, Bauer A, Schultz J, Rick JM, Michon AM, Cruciat CM, et al. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature. 2002;415:141–147. doi: 10.1038/415141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Liu Z, Church GM, Vidal M. Correlation between transcriptome and interactome mapping data from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Genet. 2001;29:482–486. doi: 10.1038/ng776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Walhout AJ, Vidal M. Integrating 'omic' information: a bridge between genomics and systems biology. Trends Genet. 2003;19:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G, Chu AM, Ni L, Connelly C, Riles L, Veronneau S, Dow S, Lucau-Danila A, Anderson K, Andre B, et al. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature. 2002;418:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giot L, Bader JS, Brouwer C, Chaudhuri A, Kuang B, Li Y, Hao YL, Ooi CE, Godwin B, Vitols E, et al. A protein interaction map of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2003;302:1727–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.1090289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh KI, Cusick ME, Valle D, Childs B, Vidal M, Barabasi AL. The human disease network. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8685–8690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701361104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriev A. A relationship between gene expression and protein interactions on the proteome scale: analysis of the bacteriophage T7 and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3513–3519. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove CA, De Masi F, Barrasa MI, Newburger DE, Alkema MJ, Bulyk ML, Walhout AJ. A multiparameter network reveals extensive divergence between C. elegans bHLH transcription factors. Cell. 2009;138:314–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunsalus KC, Ge H, Schetter AJ, Goldberg DS, Han JD, Hao T, Berriz GF, Bertin N, Huang J, Chuang LS, et al. Predictive models of molecular machines involved in Caenorhabditis elegans early embryogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:861–865. doi: 10.1038/nature03876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jr, Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JD, Bertin N, Hao T, Goldberg DS, Berriz GF, Zhang LV, Dupuy D, Walhout AJ, Cusick ME, Roth FP, et al. Evidence for dynamically organized modularity in the yeast protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2004;430:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature02555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA. DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination. Genome Res. 2000;10:1788–1795. doi: 10.1101/gr.143000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo CA, Blumm N, Barabasi AL, Christakis NA. A dynamic network approach for the study of human phenotypes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y, Gruhler A, Heilbut A, Bader GD, Moore L, Adams SL, Millar A, Taylor P, Bennett K, Boutilier K, et al. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature. 2002;415:180–183. doi: 10.1038/415180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Chiba T, Ozawa R, Yoshida M, Hattori M, Sakaki Y. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4569–4574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061034498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Tashiro K, Muta S, Ozawa R, Chiba T, Nishizawa M, Yamamoto K, Kuhara S, Sakaki Y. Toward a protein-protein interaction map of the budding yeast: A comprehensive system to examine two-hybrid interactions in all possible combinations between the yeast proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1143–1147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanic J, Yu X, Wallqvist A, Reifman J. Influence of protein abundance on high-throughput protein-protein interaction detection. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger S, Gulbahce N, Cimermancic P, Kane J, He N, Chou S, D'Orso I, Fernandes J, Jang G, Frankel AD, et al. Purification and characterization of HIV-human protein complexes. Methods. 2010;53:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen R, Greenbaum D, Gerstein M. Relating whole-genome expression data with protein-protein interactions. Genome Res. 2002;12:37–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.205602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Mason SP, Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature. 2001;411:41–42. doi: 10.1038/35075138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabasi AL. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000;407:651–654. doi: 10.1038/35036627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen W. Elemente der exakten Erblichkeitslehre (Jena, Gustav Fischer) 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson PF, Bates PA. Global topological features of cancer proteins in the human interactome. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2291–2297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan IK, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. No simple dependence between protein evolution rate and the number of protein-protein interactions: only the most prolific interactors tend to evolve slowly. BMC Evol Biol. 2003;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahali B, Ahmad S, Ghosh TC. Exploring the evolutionary rate differences of party hub and date hub proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein-protein interaction network. Gene. 2009;429:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, Hattori M, Hirakawa M, Itoh M, Katayama T, Kawashima S, Okuda S, Tokimatsu T, et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D480–484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karginov FV, Conaco C, Xuan Z, Schmidt BH, Parker JS, Mandel G, Hannon GJ. A biochemical approach to identifying microRNA targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19291–19296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709971104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmeren P, van Berkum NL, Vilo J, Bijma T, Donders R, Brazma A, Holstege FC. Protein interaction verification and functional annotation by integrated analysis of genome-scale data. Mol Cell. 2002;9:1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Lund J, Kiraly M, Duke K, Jiang M, Stuart JM, Eizinger A, Wylie BN, Davidson GS. A gene expression map for Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;293:2087–2092. doi: 10.1126/science.1061603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Cagney G, Yu H, Zhong G, Guo X, Ignatchenko A, Li J, Pu S, Datta N, Tikuisis AP, et al. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006;440:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature04670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhner S, van Noort V, Betts MJ, Leo-Macias A, Batisse C, Rode M, Yamada T, Maier T, Bader S, Beltran-Alvarez P, et al. Proteome organization in a genome-reduced bacterium. Science. 2009;326:1235–1240. doi: 10.1126/science.1176343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, Devon K, Dewar K, Doyle M, FitzHugh W, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DS, Park J, Kay KA, Christakis NA, Oltvai ZN, Barabasi AL. The implications of human metabolic network topology for disease comorbidity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9880–9885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802208105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Lehner B, Vavouri T, Shin J, Fraser AG, Marcotte EM. Predicting genetic modifier loci using functional gene networks. Genome Res. 2010;20:1143–1153. doi: 10.1101/gr.102749.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Feinbaum R, Ambros V. A short history of a short RNA. Cell. 2004;116:S89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Robert F, Odom DT, Bar-Joseph Z, Gerber GK, Hannett NM, Harbison CT, Thompson CM, Simon I, et al. Transcriptional regulatory networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;298:799–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1075090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Armstrong CM, Bertin N, Ge H, Milstein S, Boxem M, Vidalain PO, Han JD, Chesneau A, Hao T, et al. A map of the interactome network of the metazoan C. elegans. Science. 2004;303:540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.1091403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Hao T, Shaw C, Patel AJ, Szabo G, Rual JF, Fisk CJ, Li N, Smolyar A, Hill DE, et al. A protein-protein interaction network for human inherited ataxias and disorders of Purkinje cell degeneration. Cell. 2006;125:801–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Sorokin A, Mazein A, Selkov A, Selkov E, Demin O, Goryanin I. The Edinburgh human metabolic network reconstruction and its functional analysis. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:135. doi: 10.1038/msb4100177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhani HD, Styles CA, Fink GR. MAP kinases with distinct inhibitory functions impart signaling specificity during yeast differentiation. Cell. 1997;91:673–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani R, St Onge R, Hartman Jt, Giaever G, Roth F. Defining genetic interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3461–3466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712255105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte E, Date S. Exploiting big biology: integrating large-scale biological data for function inference. Brief Bioinform. 2001;2:363–374. doi: 10.1093/bib/2.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez NJ, Ow MC, Barrasa MI, Hammell M, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Roth FP, Ambros VR, Walhout AJ. A C. elegans genome-scale microRNA network contains composite feedback motifs with high flux capacity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2535–2549. doi: 10.1101/gad.1678608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Rios J, Uetz P. Global approaches to study protein-protein interactions among viruses and hosts. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:289–301. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R, Itzkovitz S, Kashtan N, Levitt R, Shen-Orr S, Ayzenshtat I, Sheffer M, Alon U. Superfamilies of evolved and designed networks. Science. 2004;303:1538–1542. doi: 10.1126/science.1089167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R, Shen-Orr S, Itzkovitz S, Kashtan N, Chklovskii D, Alon U. Network motifs: simple building blocks of complex networks. Science. 2002;298:824–827. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5594.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]