Abstract

Population studies have revealed that Candida albicans can be separated into five major clades, groups I, II, III, SA, and E. Groups SA and E are highly prevalent in South Africa and Europe, respectively, while group II is excluded from the southwestern portion of the United State. In each geographical locale, several clades exist side by side, suggesting little interclade recombination. These results suggest clade-specific phenotypes. In the present study we demonstrate that resistance to flucytosine (5FC MIC ≥ 32 μg/ml), an antifungal used for the treatment of systemic C. albicans infections, is restricted to clade I. In addition, while 97% of all strains for which 5FC MICs were ≥0.5 μg per ml were members of group I, only 3% were members of the other groups. 5FC MICs were ≥0.5 μg per ml for 72% of all group I isolates, while 5FC MICs were ≥0.5 μg per ml for only 2% of all non-group I isolates. These results demonstrate for the first time the clade specificity of a clinically relevant trait (5FC resistance) and suggest that while intraclade recombination may be common, interclade recombination is rare.

Individual strains of Candida albicans can become drug resistant through repeated exposure in vivo and in vitro (29, 36). However, the acquisition of drug resistance does not appear to afford cells with a permanent advantage, since an increase in the prevalence of drug-resistant strains worldwide has not occurred. In most discussions of drug resistance, we tend to consider all strains to be relatively equal in their capacities to evolve drug resistance and to discuss natural resistance at the species level. The assumption of general strain uniformity, however, has been challenged by the identification of deep-rooted C. albicans clades that not only maintain their integrity side by side in the same geographical locale but also exhibit geographical specificity (5, 22, 25). Using Ca3 fingerprinting, Pujol et al. (22) identified three major C. albicans clades, groups I, II, and III. Blignaut et al. (5), using the same methodology, demonstrated that in South Africa there was a fourth clade, group SA, in addition to groups I, II, and III. Isolates from group SA, which made up roughly half of all isolates from South Africa, were absent from the original U.S. collection analyzed by Pujol et al. (22), suggesting that group SA was highly prevalent in South Africa. Pujol et al. (25) then identified a fifth clade, group E, which was highly prevalent in Europe. Isolates in this clade were also absent from the original collection of Pujol et al. (25) and made up only 1% of South African isolates. With an expanded collection of North American isolates, Pujol et al. (25) demonstrated that the major clades were indeed groups I, II, and III and that groups SA and E made up only 2 and 1% of the collection, respectively. These population characteristics suggest that members of a particular clade may share clade-specific phenotypic characteristics, including resistance to antifungal drugs. In the study described here we have tested whether clades can differ in their general susceptibilities to flucytosine (5FC).

5FC is a pyrimidine analog that enters cells through the action of a permease and is then converted to 5-fluorouracil. 5-Fluorouracil can interfere with RNA synthesis or can inhibit DNA synthesis. Strains can readily develop resistance to 5FC in vitro by exposure to the drug (34). Indeed, because cells readily develop resistance to 5FC, it is usually administered with amphotericin B (1, 29). To test whether clades differ in their susceptibilities to 5FC, we have analyzed the genetic relatedness of natural isolates identified as resistant to 5FC in large screens and have compared the susceptibilities of isolates from each of the five clades of C. albicans. Our results demonstrate that all natural strains of C. albicans resistant to 5FC are members of the group I clade and that while the 5FC MIC was ≥0.5 μg per ml for 72% of all group I isolates, the 5FC MIC was ≥0.5 μg per ml for only 2% of all non-group I isolates. These results provide the first genetic evidence for clade-specific drug resistance and imply that while recombination rarely occurs between isolates of different clades, it may occur more frequently between isolates of the same clade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. albicans isolates.

Isolates were collected from blood or sterile body fluids from patients at more than 42 different geographical sites participating in the SENTRY surveillance program (19); 164 isolates were from 19 sites in the United States and Canada, 46 isolates were from 11 sites in Europe, 22 isolates were from 4 sites in South America, and 11 isolates were from 3 sites in Turkey and Israel. The isolates were not exposed to any antifungal agent prior to collection. The isolates were initially plated on blood agar and Sabouraud dextrose agar at the original site of collection and were then sent to the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics for banking and further analysis. Upon receipt, each isolate was subcultured onto potato dextrose agar (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) and CHROMagar (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Maria, Calif.) to assess viability and species homogeneity. The isolates were identified as C. albicans with Vitek and API kits (bioMerieux, St. Louis, Mo.). Clonal isolates were stored as water suspensions at ambient temperature.

DNA fingerprinting.

All isolates were fingerprinted by Southern blot hybridization with the complex DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 (2, 13, 23, 28) by methods previously described in detail (30, 31, 32). In brief, DNA was extracted from the cells, digested with EcoRI, and electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel at 50 V. The DNA was then transferred to a Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) by capillary blotting, prehybridized with salmon sperm DNA, hybridized overnight with the 32P-labeled Ca3 probe, and autoradiographed.

Computer-assisted cluster analysis.

Autoradiogram images were digitized into the DENDRON software database (31). Hybridization patterns were unwarped, processed, and then automatically scanned to identify all bands and to link common bands by using DENDRON software (31). The patterns of all test isolates were then compared in a pairwise fashion, and similarity coefficients (SAB) were computed according to the formula for the Dice coefficient (31, 32). An SAB threshold of 0.7 was selected for determination of groups in cluster analyses (5, 22, 31).

Drug susceptibility testing.

Antifungal drug susceptibility testing was performed by the reference broth microdilution method described in National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards document M27-A (18). 5FC was obtained from Sigma. Serial dilutions were made in RPMI 1640 medium buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid. Microdilution trays containing arrays of 5FC at final dilutions of 0.06 to 128 μg/ml were prepared in a single lot. The trays were stored at −70°C prior to use. Prior to testing, each isolate was passaged once on potato dextrose agar to ensure that it had optimal growth characteristics. One hundred microliters of a suspension of cells that varied in concentration from 0.5 × 103 to 2.5 × 103 cells per ml was added to each well of a microdilution tray. The trays were incubated in air at 35°C, and MIC endpoints were read after 48 h. Drug- and yeast-free controls were included in each tray. Following incubation, the growth in each well was compared visually with that in control wells. The MICs were defined as the lowest concentration resulting in a prominent decrease in turbidity. Quality control of the susceptibility assay was performed by using reference isolates Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22091 and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 (4, 18). The categories of 5FC susceptibility were interpreted according to the following breakpoints (18, 27): susceptibility, ≤4 μg per ml; intermediate resistance, 8 to 16 μg per ml; resistance, ≥32 μg per ml.

RESULTS

The five major clades of C. albicans.

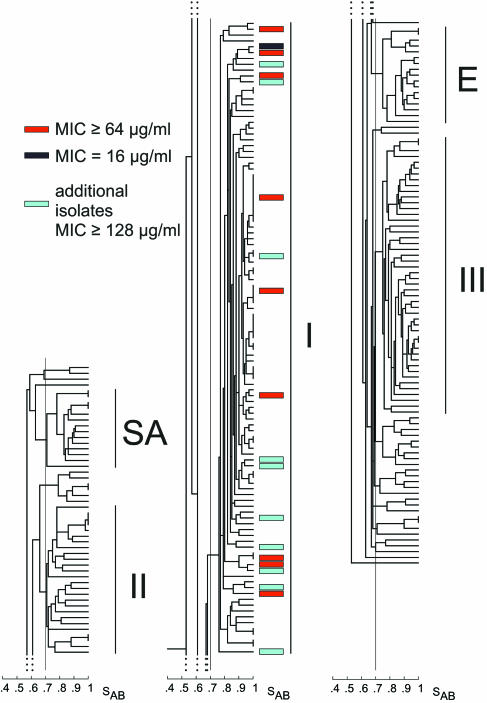

We generated a dendrogram that includes a basic collection of 243 C. albicans isolates that were DNA fingerprinted with the complex probe Ca3 (Fig. 1). The basic collection included 99 group I isolates, 26 group II isolates, 48 group III isolates, 14 group SA isolates, 17 group E isolates, and 39 outliers (isolates that did not cluster in the five major groups). These isolates were selected from our general collections to represent all major groups and outliers. All of these isolates were DNA fingerprinted and were then analyzed for 5FC susceptibility.

FIG. 1.

5FC resistance is restricted to group I isolates of C. albicans, as demonstrated by cluster analysis of a collection of 253 natural C. albicans isolates. The five major C. albicans clades (groups I, II, III, SA, and E) are shown. For presentation purposes, the dendrogram has been separated into three sections, the top (groups SA and II), middle (group I), and bottom (groups E and III), from left to right, respectively. The red boxes indicate the positions of the 9 isolates resistant to 5FC (MIC ≥ 32 μg/ml) identified among a randomly selected collection of 243 isolates, and the black box indicates the single isolate with intermediate resistance (MIC = 16 μg/ml) identified among those isolates. The blue boxes indicate the positions of the 10 isolates resistant to 5FC (MIC ≥ 128 μg/ml) that were identified in a previous analysis of 5,208 isolates (20). Note that all of those natural isolates that are resistant to 5FC are members of group I.

All 5FC-resistant strains are in group I.

Of the 243 isolates tested, 9 (3.7%) proved to be 5FC resistant (i.e., MIC ≥ 32 μg per ml). The MIC for one isolate was intermediate (MIC = 16 μg per ml). When these 10 isolates were color coded red and black, respectively, in the dendrogram presented in Fig. 1, it was revealed that they all clustered exclusively in group I.

Ten additional isolates highly resistant to 5FC (MICs ≥ 128 μg per ml) were identified in a separate screen of a collection of 5,208 C. albicans isolates (20). These isolates were DNA fingerprinted with Ca3 and added to the dendrogram of the collection of 243 isolates, in which they were color coded blue (Fig. 1). All 10 isolates also clustered exclusively in group I. These results indicate that among natural isolates, 5FC resistance is specific to group I.

In general, resistant strains appeared to be distributed throughout cluster I, suggesting a random distribution (Fig. 1). However, there were four examples of subclusters of two and three 5FC-resistant isolates, defined by an SAB threshold of 0.90.

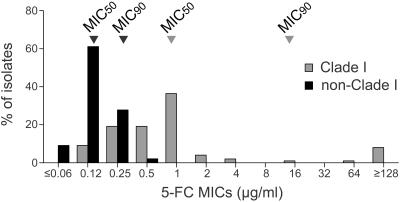

Group I isolates are in general less susceptible to 5FC.

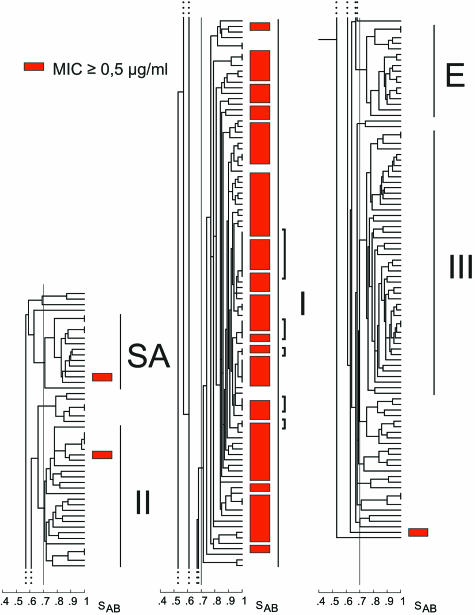

The results presented in Fig. 1 indicate that resistant strains are restricted to group I. However, resistant strains represented only 4% of group I isolates. To test whether group I isolates in general were less susceptible to 5FC than non-group I isolates, a histogram of the MICs for group I and non-group I isolates was generated (Fig. 2). The distributions were significantly different. While the MICs for non-group I isolates were distributed between ≤0.06 and 0.50 μg per ml, with an MIC at which 50% of isolates tested are inhibited (MIC50) of 0.12 μg per ml, the MICs for group I isolates were distributed between 0.12 and ≥128 μg per ml, with an MIC50 of 1.00 μg per ml, a value eight times higher than that for non-group I isolates (Fig. 2). When 0.50 μg per ml was used as an arbitrary MIC threshold for strains with decreased 5FC susceptibility, 97% of isolates for which the MIC was ≥0.50 μg per ml proved to be in group I, while the remaining 3% were in groups other than group I. The disproportionate concentration of less susceptible isolates in group I is demonstrated in the dendrogram in Fig. 3, in which all isolates for which MICs were ≥0.50 μg per ml are color coded red. All but 3 of the 78 strains for which the MIC was ≥0.50 μg per ml (97%) clustered in group I. Less susceptible isolates made up 72% of group I isolates but only 2% of non-group I isolates.

FIG. 2.

The 5FC MIC distributions differ between the 99 group I and 144 non-group I isolates. The MIC50s and MIC90s are indicated for each group of isolates; black arrowheads point to the results for non-group I isolates, and gray arrowheads point to the results for group I isolates. The two distributions were significantly different (P < 0.001 by both the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Fisher's exact tests).

FIG. 3.

Group I isolates are, on average, less susceptible to 5FC than non-group I isolates. In a cluster analysis of a collection of 243 C. albicans isolates, the positions of isolates for which 5FC MICs were≥0.50 μg/ml are indicated by red boxes. The large majority of isolates (97%) for which MICs were ≥0.50 μg/ml were members of group I. The brackets indicate the five groups of isolates that have identical patterns by fingerprinting with the Ca3 probe and that differ in their susceptibilities to 5FC.

The distribution of less susceptible isolates in the group I cluster appeared to be randomly distributed (Fig. 3). More susceptible isolates did not cocluster. In addition, there were five examples within the group I cluster of isolates with identical patterns by fingerprinting with probe Ca3 (i.e., SAB = 1.00) that differed in their susceptibilities (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Using DNA fingerprinting with the complex probe Ca3, Pujol et al. (22) identified three major clades of C. albicans, groups I, II, and III, among a limited collection of 26 unrelated U.S. isolates. Pujol et al. (22) demonstrated that the clustering capacity of the Ca3 fingerprinting method was similar to those of the multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA methods, thus verifying its clustering efficacy and the integrity of the three clades (31). Blignaut et al. (5) subsequently demonstrated that in addition to groups I, II, and III, a fourth clade, group SA, accounted for 55% of all isolates from black individuals and 33% of all isolates from white individuals in South Africa. Group SA was absent from the original collection of 26 U.S. isolates of Pujol et al. (22). Pujol et al. (25) subsequently identified a fifth clade, group E, to which 26% of all European isolates belonged. Since groups SA and E each contained only 2% North American isolates and group E contained only 1% South African isolates, groups SA and E were considered geographically specific. Furthermore, Pujol et al. (25) demonstrated that group II was missing from the southwestern United States. Because human populations are mobile and mix, geographical specificity has been interpreted to reflect both differences in nonhuman reservoir populations and phenotypic differences between clades (33). However, because the discoveries of geographical specificity are new, no phenotypic differences have been reported, until now.

In the present study, we have tested whether clades exhibit differences in drug susceptibility by cluster analysis of 5FC-resistant isolates and isolates less susceptible to 5FC. Our results demonstrate that isolates that are naturally 5FC resistant are restricted to group I and that group I isolates are generally less susceptible to 5FC than non-group I isolates. Isolates of group I represent 47% of isolates in North America (25), 20% of isolates in Europe (25), and 19% of isolates in South Africa (5). Therefore, group I represents a major C. albicans clade in all of the geographical regions so far studied.

In prior studies, there were already indications that 5FC resistance was not equally distributed among strains. 5FC resistance was associated with, but was not restricted to, one of the two serotypes of C. albicans, serotype B (3, 7, 35). However, since the two C. albicans serotypes have been shown to be interconvertible within a strain (21), the association with 5FC resistance that was demonstrated was not necessarily genotypic. Prior studies also indicated that 5FC resistance is associated with the absence of the ribosomal IS1 intron (17). However, this association is not tight, since both group I and group II isolates lack this intron (5, 15, 25), but only group I isolates are resistant. Our results therefore appear to be the first to relate a single bona fide genetic group of C. albicans with a drug resistance phenotype. Our studies, however, did not test whether the average clade I isolate more readily acquires resistance upon exposure to 5FC than non-group I isolates, even though group I isolates are, on average, already less susceptible to the drug. Experiments to test this question are in progress.

Finally, our results provide some insight into the process of recombination in C. albicans. Recently, Hull and Johnson (9) identified the mating locus of C. albicans, and mating type-dependent fusion has been demonstrated both by complementation (10, 16) and at the cellular level (11, 12). Although these observations provide a formal mechanism for recombination, population studies suggest a clonal population structure (6, 8, 26), suggesting that recombination, at least between clades, is a rare event. The recent observation that clades remain intact side by side in the same geographical locale (5, 22, 25, 33) supports the idea that recombination is rare between isolates of different clades. In the present study we have demonstrated that natural drug resistance and a general decrease in susceptibility are exclusive characteristics of only one of the five clades, lending support to the idea that little recombination occurs between isolates of group I and isolates from the four other clades. On the other hand, decreased 5FC susceptibility appeared to be distributed randomly throughout clade I, suggesting that recombination within the clade may homogenize the characteristic. Two recent findings support this hypothesis. First, homozygous MTLa and MTLα strains are relatively frequent in group I (14). Second, acquisition of mating competency due to a spontaneous loss of heterozygosity at the MTL locus has been described in C. albicans strains (14, 24). Most of the strains for which this phenomenon was observed were from group I, suggesting that MTL homozygosity may be generated more frequently in this group. However, one cannot rule out the possibility that a single clone that was originally less susceptible to 5FC and that was prevalent worldwide led to clade I. The latter possibility seems unlikely, given the genetic individuality and deep-rootedness of clade I.

The results presented here have demonstrated clear differences in 5FC susceptibility between clades and suggest that other phenotypic characteristics may differ between clades. The results demonstrate that no single strain represents the entire C. albicans species and that the characterization of C. albicans for a particular virulence characteristic should therefore include representatives from each clade.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grant AI39735 (to D.R.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abele-Horn, M., A. Kopp, U. Sternberg, A. Ohly, A. Dauber, W. Russwurm, W. Buchinger, O. Nagengast, and P. Emmerling. 1996. A randomized study comparing fluconazole with amphotericin B/5-fluorocytosine for the treatment of systemic Candida infections in intensive care patients. Infection 24:426-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, J., T. Srikantha, B. Morrow, S. H. Miyasaki, T. C. White, N. Agabian, J. Schmid, and D. R. Soll. 1993. Characterization and partial nucleotide sequence of the DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 of Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1472-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auger, P., C. Dumas, and J. Joly. 1979. A study of 666 strains of Candida albicans: correlation between serotype and susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine. J. Infect. Dis. 139:590-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry, A. L., M. A. Pfaller, S. D. Brown, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, C. Knapp, R. P. Rennie, J. H. Rex, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2000. Quality control limits for broth microdilution susceptibility tests of ten antifungal agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3457-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blignaut, E., C. Pujol, S. R. Lockhart, S. Joly, and D. R. Soll. 2002. Ca3 fingerprinting of Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive and healthy individuals reveals new clade in South Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:826-836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowen, L. E., C. Sirjusingh, R. C. Summerbell, S. Walmsley, S. Richardson, L. M. Kohn, and J. B. Anderson. 1999. Multilocus genotypes and DNA fingerprints do not predict variation in azole resistance among clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2930-2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drouhet, E., L. Mercier-Soucy, and S. Montplaisir. 1975. Sensibilité et résistance des levures pathogens aux 5-fluoropyrimidines. I. Relation entre les phenotypes de résistance à la 5-fluorocytosine, le sérotype de Candida albicans et l'écologie de différentes espèces de Candida d'origine humaine. Ann. Microbiol. 126B:25-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gräser, Y., M. Volovsek, J. Arrington, G. Schönian, W. Presber, T. G. Mitchell, and R. Vilgalys. 1996. Molecular markers reveal that population structure of the human pathogen Candida albicans exhibits both clonality and recombination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:12473-12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hull, C. M., and A. D. Johnson. 1999. Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science 285:1271-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hull, C. M., R. M. Raisner, and A. D. Johnson. 2000. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in mammals. Science 289:307-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lachke, S. A., S. R. Lockhart, K. J. Daniels, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Skin facilitates Candida albicans mating. Infect. Immun. 71:4970-4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lockhart, S. R., K. J. Daniels, R. Zhao, D. Wessels, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Cell biology of mating in Candida albicans. Eukarot. Cell 2:49-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockhart, S. R., J. J. Fritch, A. S. Meier, K. Schröppel, T. Srikantha, R. Galask, and D. R. Soll. 1995. Colonizing populations of Candida albicans are clonal in origin but undergo microevolution through C1 fragment reorganization as demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting and C1 sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:1501-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockhart, S. R., C. Pujol, K. J. Daniels, M. G. Miller, A. D. Johnson, and D. R. Soll. 2002. In Candida albicans, white-opaque switchers are homozygous for mating type. Genetics 162:737-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lott, T. J., B. P. Holloway, D. A. Logan, R. Fundyga, and J. Arnold. 1999. Towards understanding the evolution of the human commensal yeast Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:1137-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magee, B. B., and P. T. Magee. 2000. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTLa and MTLα strains. Science 289:310-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercure, S., S. Montplaisir, and G. Lema. 1993. Correlation between the presence of a self-splicing intron in the 25S rDNA of C. albicans and strain susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:6020-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast. Approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 19.Pfaller, M. A., D. J. Diekema, R. N. Jones, H. S. Sader, A. C. Fluit, R. J. Hollis, S. A. Messer, and The SENTRY Participant Group. 2001. International surveillance of bloodstream infections due to Candida species: frequency of occurrence and in vitro susceptibilities to fluconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole of isolates collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3254-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, L. Boyken, H. Huynh, R. J. Hollis, and D. J. Diekema. 2002. In vitro activities of 5-fluorocytosine against 8,803 clinical isolates of Candida spp.: global assessment of primary resistance using National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards susceptibility testing methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3518-3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poulain, D., V. Hopwood, and A. Vernes. 1985. Antigenic variability of Candida albicans. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 12:223-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pujol, C., S. Joly, S. R. Lockhart, S. Noel, M. Tibayrenc, and D. R. Soll. 1997. Parity among the randomly amplified polymorphic DNA method, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and Southern blot hybridization with the moderately repetitive DNA probe Ca3 for fingerprinting Candida albicans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2348-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pujol, C., S. Joly, B. Nolan, T. Srikantha, and D. R. Soll. 1999. Microevolutionary changes in Candida albicans identified by the complex Ca3 fingerprinting probe involve insertions and deletions of the full-length repetitive sequence RPS and specific genomic sites. Microbiology 145:2635-2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pujol, C., S. A. Messer, M. Pfaller, and D. R. Soll. 2003. Drug resistance is not directly affected by mating type locus zygosity in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1207-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pujol, C., M. Pfaller, and D. R. Soll. 2002. Ca3 fingerprinting of Candida albicans bloodstream isolates from the United States, Canada, South America, and Europe reveals a European clade. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2729-2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pujol, C., F. Reynes, M. Renaud, M. Raymond, M. Tibayrenc, F. J. Snyder, F. Janbon, M. Mallie, and J. M. Bastite. 1993. The yeast Candida albicans has a clonal mode of reproduction in a population of infected human immunodeficiency virus positive patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:9456-9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rex, J. H., M. A. Pfaller, J. N. Galgiani, M. S. Bartlett, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, M. Lancaster, F. C. Odds, M. G. Sinald, T. J. Walsh, and A. L. Barry. 1997. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro:in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadhu, C., M. J. McEachern, E. P. Rustchenko-Bulgac, J. Schmid, D. R. Soll, and J. Hicks. 1991. Telomeric and dispersed repeat sequences in Candida yeasts and their use in strain identification. J. Bacteriol. 173:842-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanglard, D., and J. Bille. 2002. Current understanding of the modes of action of and resistance mechanisms to conventional and emerging antifungal agents for treatment of Candida infections, p. 349-383. In R. A. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington D.C.

- 30.Schmid, J., E. Voss, and D. R. Soll. 1990. Computer-assisted methods for assessing strain relatedness in Candida albicans by fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive sequence Ca3. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1236-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soll, D. R. 2000. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:332-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soll, D. R., S. R. Lockhart, and C. Pujol. 2003. Laboratory procedures for the epidemiological analysis of microorganisms, p. 139-161. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, J. H. Jorgensen, M. A. Pfaller, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, vol. 1, 8th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 33.Soll, D. R., and C. Pujol. 2003. Candida albicans clades. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 39:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stiller, R. L., J. E. Bennett, H. J. Scholer, M. Wall, A. Polak, and D. A. Stevens. 1983. Correlation of in vitro susceptibility test results with in vivo response: flucytosine therapy in a systemic candidiasis model. J. Infect. Dis. 147:1070-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stiller, R. L., J. E. Bennett, H. J. Scholer, M. Wall, A. Polak, and D. A. Stevens. 1982. Susceptibility to 5-fluorocytosine and prevalence of serotype in 402 Candida albicans isolates from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:482-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White, T. C., K. A. Marr, and R. A. Bowden. 1998. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:382-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]