Abstract

Teratomas of the head and neck due to their obscure origin, bizarre microscopic appearance, unpredictable behaviour and often dramatic clinical presentation are a clinical surprise. This article focuses on pediatric head and neck teratomas and on their diversity and rarity and also reviews the recent terminology of this group of tumours.

Keywords: Teratomas, Children, Cervical teratomas, Nasopharyngeal teratomas, Head and neck teratomas

Introduction

Teratomas of the head and neck are interesting because of their obscure origin, bizarre microscopic appearance, unpredictable behaviour and often dramatic clinical presentation. Teratomas are embryonal neoplasms that arise when totipotential germ cells escape the developmental control of primary organizers and give rise to more or less organoid masses in which tissues derived from all three blastodermic layers (ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm) can be identified. Their histologic features are therefore heterogenous and may include cystic or solid areas with organoid patterns as well as mature or immature components.

Head neck teratomas are rare benign tumors consisting of 3% of all teratomas [1]. In children they are usually diagnosed early due to the frequent symptoms such as respiratory distress, facial disfigurement and orbital involvement. Unlike adults, teratomas in children are often congenital and very rarely turn malignant. An otolaryngologist should be aware of their natural history, clinical features, pathology and principles of management. This article focuses on the diversity and rarity of this group of tumours and also reviews the terminology of these tumours.

Case Report

We report three cases of teratomas.

Case 1

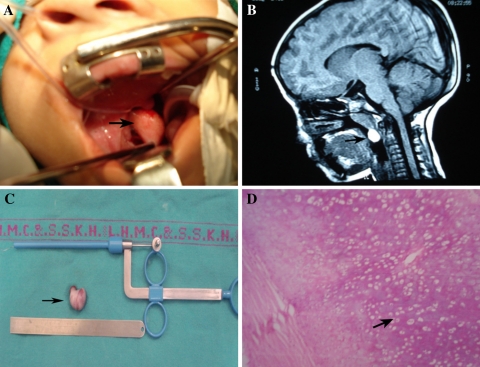

A 7 year old girl presented with complaints of increasing difficulty in nasal breathing and difficulty in swallowing solid food for past 6 months. Patient snored loudly during the night and she frequently woke up choking. Clinical examination revealed a large and round, pink 2.5 × 2.5 cm smooth, globular mass seen hanging in the oropharynx with absent cough impulse (Fig. 1A). Endoscopic examination showed a pedunculated nasopharyngeal mass arising from right lateral nasopharyngeal wall. MRI showed an area of T1/T2 bright signals measuring 17 × 9 mm (Fig. 1B). There was no intracranial extension. Intraoperatively, the mass was attached to the lateral wall of nasopharynx through a cartilaginous peduncle (Fig. 1C). Tumor was excised completely under general anaesthesia. Histopathology of the specimen showed mature teratoma (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Features suggestive of nasopharyngeal teratioma; A Clinical photograph; B MRI scan; C Excised specimen; D Microphotograph

Case 2

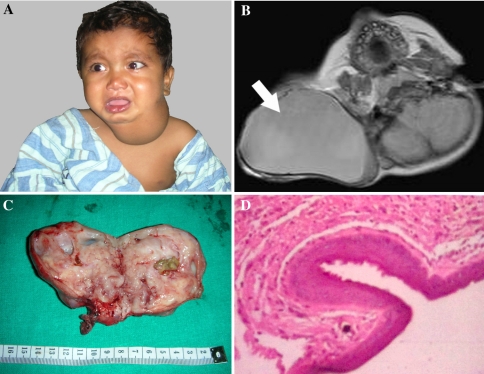

17 month old male child presented with left side neck swelling since birth. There was no history of respiratory distress, dysphagia, and odynophagia. On examination, there was a firm lobular mobile mass measuring 10 × 6 cm with well defined margins on left side neck (Fig. 2A). Contrast enhanced computed tomography showed large, heterogeneous well defined mass measuring 7.14 × 5.7 × 6.5 cm with areas of central necrosis as well as multiple calcified foci, suggestive of teratoma (Fig. 2B). Pre operative FNAB was suggestive of teratoma. Intraoperatively, it was well capsulated mass, abutting the pretracheal fascia medially and the carotid sheath laterally. All the vital structures were preserved and the mass was removed in toto. Grossly it was an 8 × 6 cm size encapsulated solid mass with bosselated surface, with few cystic areas and focal dark brown gelatinous areas (Fig. 2C). Microscopic examination showed mature glial tissue with psammomatous calcific deposits and numerous cystic spaces lined by simple and stratified columnar and squamous epithelia, which was suggestive of mature cystic teratoma (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Teratoma neck; A Clinical Photograph; B CECT neck showing heterogenous well defined mass with multiple calcific foci; C Excised specimen; D Microphotograph showing mature glial tissue with psammomatous calcific deposits suggestive of mature cystic teratoma

Case 3

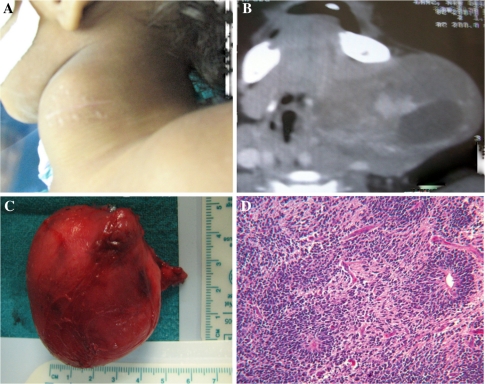

A 2 year old male child presented with gradually progressive left side neck swelling since birth. On examination of neck, there was a 6 × 6 cm size mobile and non tender swelling with well defined margins and soft to firm in consistency (Fig. 3A). FNAB was suggestive of mature teratoma. A CECT neck showed multiple calcified areas mixed with cystic spaces (Fig. 3B). Excision was done under general anesthesia and the mass was removed in toto. Grossly, it was a 6 × 6 × 4 cm size well capsulated mass with lobulated surface (Fig. 3C). Histopathology report was suggestive of mature cystic teratoma (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Teratoma neck; A Clinical photograph; B CECT neck showing multiple calcified areas mixed with cystic spaces; C Excised specimen (6 x 6 x 4 cm size); D Microphotograph showing mature cystic teratoma

Case 1 was of nasopharyngeal type while case 2 and case 3 are cervical type. Their clinical details have been given in Table 1. Maternal risk factor like polyhydramnios was seen in only one of the three cases. Respiratory distress and difficult feeding was encountered with only one case. Since these masses were cystic intraoperatively they resembled lymphangioma clinically. How ever in all cases a pseudo capsule was present which enabled complete dissection of the tumor. Histopathologically all specimens were teratomas with varying amount of neuroglial tissue and cystic spaces with in the mass. There were no complications or recurrence at 2 years of follow up.

Table 1.

Clinical features of head and neck teratomas of children

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenting age | 7 years | 17 months | 2 years |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male |

| Predominant symptom | Nasal obstruction | Neck mass | Neck mass |

| Difficult feeding | |||

| Location | Oronasopharyngeal | Cervical | Cervical |

| Size | 25 × 25 mm | 100 × 60 mm | 60 × 60 mm |

| Radiological features | MRI area of T1/T2 bright signals measuring 17 × 9 mm | MRI well defined mass with areas of central necrosis and multiple areas of calcifications showing as hypointense areas. | CT well defined mass with areas of central necrosis and multiple areas of calcifications |

| Management | Surgical excision | Surgical excision | Surgical excision |

| Recurrence | None | None | None |

| Maternal risk factors | None | Polyhydramnios | None |

| Histopathological type | Mature | Immature | Mature |

| Preoperative FNAB | Not done | Teratoma | Teratoma |

FNAB fine needle aspiration biopsy

Discussion

According to Batsakis teratoma is composed of tissue foreign to the site of origin and histological representation of all three germ layer [2]. Other germ cell tumors resembling teratoma are hamartoma, choristoma, and dermoid. Hamartoma contains tissue that is indigenous to the site of its growth. Choristoma is similar to hamartoma in terms of normal tissue growth potential but the tissue is foreign to the site of origin [3]. While dermoids are germ cell tumor having both ectodermal and mesodermal components with growth potential. Even benign teratomas have unlimited growth potential [3]. These tumours are generally rare, with an incidence of one in 4,000 live births [4], have no gender predominance, and have an 18% risk of other congenital malformations [4, 5].

Only 5% of all teratomas occur in the head and neck region, predominantly in the cervical, nasopharynx, face, and orbit. The reported incidence of cervical teratomas ranges from 2.3 to 9.3% of the total [6].

Cervical teratomas in children are almost always benign but locally aggressive. They can present with respiratory distress and immediate excision is required. Our first case, although presented with mild respiratory distress but it was not life threatening.

Nasopharyngeal teratomas may be sessile or pedunculated, and have been reported to protrude from the mouth and nares. One of the most severe forms of nasopharyngeal teratoma is an epignathus. It is a large oronasopharyngeal teratoma with disfiguring mass presenting in the neonate [7]. This tumor is protrudes from the oral cavity and has attachment to the palate/skull base or is contiguous with intracranial component. Diagnosis is usually made early in infancy and rarely after 2 years of age. Teratomas of the nasopharynx are often associated with cranial structural anomalies. Palatal fissures are common and hemicrania and anencephaly have been reported. It is theorized that the teratoma physically interferes with the normal fusion of embryonic tissues in the early developmental period [3]. Our case number one was oronasopharyngeal type and it was arising from the lateral nasopharyngeal wall through a stalk. None of the above anomalies were seen in any of our case one.

Radiologically, presence of multiple calcified foci in computerized tomography is highly suggestive of teratomas [3]. CT also helps in defining the extent of the lesion as well as intracranial extension. Despite CT scanning, teratomas have been misdiagnosed for meningoencephaloceles and hence intraoperative aspiration has been recommended before the excision. Other radiographic investigation for diagnosis of teratoma is suggested by the presence of calcifications on the plain film or mixed echogenicity with multi-loculated cystic or solid regions on ultrasonography. Radiological differential diagnoses of teratoma are lymphangioma, venous malformations with phleboliths, dermoid, neurenteric cysts, Thornwalds cyst, and basal meningocele. Preoperative thyroid function tests should be done in all cervical teratomas as they frequently contain thyroid tissue and post operative hypothyroidism is very common [3, 6]. None of our cases experienced any post operative hypothyroidism. Unlike adults, pediatric teratomas usually do not turn malignant but serum alpha feta protein can be used as a marker for malignancy. Recently, FNAB has been described to assess the possibility of malignant changes. Differentiation from glial tumors often requires excisional biopsy since nasopharyngeal teratomas can be predominantly composed of neural tissue. Our first case was an immature teratoma consisting of nearly 70% of neuroglial tissue. Other authors have reported that on Histopathological examination immature teratomas with more neuroglial contents can be mistaken for neuroblastoma or retinoblastoma. We did not encounter similar problems. Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice for both malignant and benign teratomas [8]. Presence of endodermal sinus tumor or embryonal carcinoma is the main reasons for teratoma turning malignant. However, it has been reported that immaturity of various constituent tissues in childhood teratomas (unlike adult) does not impact on the otherwise favourable prognosis of the teratoma.

Since teratomas are often associated with polyhydramnios and congenital malformations a close cooperation among ultrasound specialists, obstetricians, anesthesiologists, pediatric surgeons, neonatologists, and pediatric otolaryngologists may be required for optimal management of head neck teratomas [9].

Conclusion

Teratomas are rare benign tumors in head neck region in children. They can potentially cause fatal airway obstruction. Surgical removal gives a complete cure. Possibility of teratoma and other congenital malformations should be kept in mind in mothers with polyhydramnios.

Acknowledgments

This study is attributed to Department of Otolaryngology and Head Neck Surgery, Lady Hardinge Medical College and Associated Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital. New Delhi-110001.

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Rothschild MA, Catalano P, Urken M, Brandwein M, Som P, Norton K, Biller HF. Evaluation and management of congenital cervical teratoma. Case report and review. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;120(4):444–448. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880280072014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rybak LP, Rapp MF, McGrady MD, Schwart MR, Myers PW, Orvidas L. Obstructing nasopharyngeal teratoma in the neonate. A report of two cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117(12):1411–1415. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870240103019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotton RT, Myer CM. Practical paediatric otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon CR, Johns ME, Fechner RE. Immature teratoma of the larynx. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;96(4):366–368. doi: 10.1177/019459988709600410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman RP, Randolph JG, Lilly JR. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: American academy of pediatrics surgical section survey-1973. J Pediatr Surg. 1974;9(3):389–398. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(74)80297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchiyama M, Iwafuchi M, Naitoh S, Matsuda Y, Naitoh M, Yagi M, Hoshi E, Nonomura N. A huge immature cervical teratoma in a newborn: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25(8):737–740. doi: 10.1007/BF00311491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calcaterra T. Teratomas of the nasopharynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1969;78(1):165–171. doi: 10.1177/000348946907800115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakhlu A, Wakhlu AK. Head and neck teratomas in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:333–337. doi: 10.1007/s003830000391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sichel JY, Eliashar R, Yatsiv I, Moshe Gomori J, Nadjari M, Springer C, Ezra Y. A multidisciplinary team approach for management of a giant congenital cervical teratoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;65(3):241–247. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(02)00154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]