Abstract

Objective

To test the responsiveness of the Infant/Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire (ITQOL) to five health conditions. In addition, to evaluate the impact of the child’s age and gender on the ITQOL domain scores.

Methods

Observational study of 494 Dutch preschool-aged children with five clinical conditions and 410 healthy preschool children randomly sampled from the general population. The clinical conditions included neurofibromatosis type 1, wheezing illness, bronchiolitis, functional abdominal complaints, and burns. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed by a mailed parent-completed ITQOL. Mean ITQOL scale scores for all conditions were compared with scores obtained from the reference sample. The effect of patient’s age and gender on ITQOL scores was assessed using multi-variable regression analysis.

Results

In all health conditions, substantially lower scores were found for several ITQOL scales. The conditions had a variable effect on the type of ITQOL domains and a different magnitude of effect. Scores for ‘physical functioning’, ‘bodily pain’, and ‘general health perceptions’ showed the greatest range. Parental impact scales were equally affected by all conditions. In addition to disease type, the child’s age and gender had an impact on HRQoL.

Conclusions

The five health conditions (each with a distinct clinical profile) affected the ITQOL scales differently. These results indicate that the ITQOL is sensitive to specific characteristics and symptom expression of the childhood health conditions investigated. This insight into the sensitivity of the ITQOL to health conditions with different symptom expression may help in the interpretation of HRQoL results in future applications.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, Preschool children, ITQOL, Variety of diseases

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is an important outcome measure in clinical studies. HRQoL adopts the WHO definition of health as being ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease’ [1]. Generic questionnaires are designed to measure all dimensions of HRQoL and can therefore be applied in both healthy populations and in any clinical setting [2]. Disease-specific HRQoL questionnaires augment generic measures by assessing the implications of a specific condition [3]. Due to the developmental stage and corresponding cognitive abilities of preschool-aged children, HRQoL measurement in these children requires a proxy rater. HRQOL measures should include age-specific domains that correspond to the child’s developmental abilities [3].

The Infant/Toddler Quality of Life Questionnaire (ITQOL) is a parent-completed generic ‘profile measure’ for HRQoL of children aged 2–72 months [4, 5]. The questionnaire has been translated and validated into Dutch with acceptable reliability and validity. Dutch reference values are available based on 410 healthy children sampled from a preventive youth care center [6]. This generic HRQOL measure has been applied to several Dutch populations with the following clinical conditions: neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [7], wheezing illness [8], hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis [9], functional abdominal complaints (FAC) [10], and burn injuries [11]. NF1 is a chronic progressive disease with usually relatively mild symptoms in early childhood; wheezing illness and FAC are chronic conditions characterized by disease-free periods and (severe) exacerbations of recurrent complaints. Both RSV bronchiolitis and burn injuries are acute conditions requiring hospitalization, followed by variable recovery phase and outcome. Although all these diseases cause any type of discomfort, FAC is mainly characterized by pain and wheezing illness, and RSV by respiratory symptoms. Cosmetic issues and parental worries about future functioning apply to both the NF1 and burn injury populations. All the above studies report significantly lower scores on several, but not identical, ITQOL scales compared to a reference population sample [6]. Although standardized approaches on how to interpret a certain change in domain scores exist [12], insight into the variety of scores between various health conditions is lacking. It is remains unclear whether observed differences can be explained by the disease course or symptoms, and whether a child’s age and/or gender contribute to these differences. Knowledge of the sensitivity of a health state measure to various health conditions (with different symptom expression) may help in the interpretation of HRQoL results.

This study tests the responsiveness of the ITQOL to five differing health conditions. The impact of children’s age and gender on the ITQOL domain scores is also evaluated.

Methods

Patients

For this study, results from five independent databases on HRQoL in the Netherlands, and responses to the ITQOL from the Dutch reference population, were used. All studies were performed independently and provided original data for the present study on ITQOL item responses, and on the children’s and parents’ general characteristics. All data were analyzed anonymously. All studies were approved by the local Medical Ethics committees.

Presented below is a brief summary of the individual studies: for detailed information we refer to previous publications.

Reference population sample

A group of 500 children (aged 3 months to 4 years) was randomly sampled from a preventive youth health care center. Response rate was 83%, resulting in a reference sample of 410 children. The percentages of sick and healthy children in this population reflected the general Dutch population [6].

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)

is a progressive neurocutaneous condition with varying disease expression [13], at young age mainly characterized by cognitive and behavioral problems [14, 15]. In 2005, participants were recruited from the multi-disciplinary pediatric NF1-outpatient clinic of the Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital Rotterdam, which is a supra-regional reference center serving about 3 million citizens [7]. The present study includes a group of 34 NF1 patients aged ≤6 years (response rate 73%).

Wheezing illness in infants and preschool children

is a disease with recurrent asthma-like symptoms, recurrent cough, wheezing and dyspnea that can vary in severity throughout the year [16]. Exacerbations can often lead to hospitalization [8, 17]. Eligible for this study were children aged 6 months to 5 years visiting the pediatric outpatient or emergency department (of either the HAGA hospital in The Hague, or Erasmus MC-Sophia in Rotterdam) between January 2000 and July 2001 with recurrent lower respiratory complaints (as described above) during at least 3 months within the previous year and treated with bronchodilators or corticosteroids (as documented in the patient record). With a response rate of 80%, and after exclusion of children with serious other pulmonary co-morbidity, a sample of 138 patients were included in the present study [8].

RSV bronchiolitis

is an acute potentially life-threatening condition of dyspnea, requiring supportive (in hospital) treatment. In most instances, RSV bronchiolitis resolves completely, but minor abnormalities of pulmonary function and airway hyper-reactivity may persist for years [17, 18]. A sample of 47 patients admitted to the hospital for RSV bronchiolitis between October 2001 and March 2002 with completed questionnaires (response rate 66%) were included in the present study (data were obtained from a large study on RSV) [9]. With the exception of one child, all had a gestational age above 35 weeks, two had epilepsy, one had neuromuscular disease, and one child had metabolic disease. Parents were asked to complete the ITQOL using their current perception of their child’s health 2–6 months after hospitalization.

Functional abdominal complaints (FAC)

Constitute one of the most common reasons for medical consultation in children [19] and may lead to many investigations and long-term follow-up at the outpatient department. Eligible patients were children aged 5–72 months that visited the pediatric outpatient clinic (January 2005–2007) with FAC [10]. FAC were defined based on the Rome criteria for children aged <4 years [20] and for children >4 years [21], including irritable bowel syndrome, functional abdominal pain, dyschezia, and functional constipation severe enough to affect activities over time. Patients with a medical history or specific symptoms suggestive of an underlying intestinal pathology or with severe psychomotor retardation were excluded. The FAC group of patients consisted of a sample of 81 patients (response rate 61%).

Burn injury

A burn injury accident is a traumatic event for a child and, if severe, requires hospitalization. Even small burns can cause a long-lasting deficit in functionality, depending on the location of the burned area [11, 22]. The burn sample consisted of all children aged 0–4 years, with a primary admission for burn injuries in one of the burn centers in the Netherlands between March 2001 and February 2004. Response rate was 50%, resulting in 194 children with a median total burned body surface of 6% (range 0–66%). The ITQOL was completed after a mean time since admission of 17.5 (SD 9.8, range 2.8–38.8) months [11].

Study questionnaire

The ITQOL is a generic parent-completed HRQoL measure. The questionnaire is comprised of 97 items (9 multi-item scales, with 3–18 items each, and 2 single-item questions) [4–6]. The ITQOL scales ‘physical functioning’, ‘growth and development’, ‘bodily pain’, ‘temperament and moods’, ‘general behavior’, ‘getting along’, and ‘general health perceptions’ measure different domains of HRQoL of the child. The ‘parental emotional impact’, ‘parental time impact’, and ‘family cohesion’ scales measure the effect of the child’s health on the parents and family life. The ‘change in health’ item measures parental perceptions of their child’s present health status when compared to the prior year. The ‘physical functioning’ scale includes a ‘not doing yet’ option; responses as such were not included in the analysis for that scale. The ‘general behavior’ and ‘getting along’ scales and the ‘change in health’ item refer to children aged 1 year and older. Items were summed and transformed into their respective scales on a 0–100 continuum that ranges from 0 (worst possible score) to 100 (best possible score) according to the standard ITQOL scoring procedure [5]. In accordance with specified scoring procedures, if a respondent missed 50% or more items of a scale, they were not included in the present analyses. Parents also completed standard demographic questions including patient’s and parent’s age and gender.

Analysis

Differences in ITQOL scale scores between the five clinical subgroups and the reference population were evaluated using one-way Anova and post hoc Bonferroni comparison tests. To interpret the observed differences, effect sizes of significant differences (P < 0.05) were calculated by dividing the difference of means by the weighted standard deviation (SD) and defined following Cohen’s guidelines: small effect 0.2 ≤ d < 0.5, moderate effect 0.5 ≤ d < 0.8, and large effect d ≥ 0.8 [12]. The influence of the patient’s age and gender additional to the impact of the health condition on ITQOL scores was investigated using multi-variable logistic regression analysis (P < 0.10).

We hypothesized that the different symptom expression of the investigated health conditions would affect ITQOL scales differently. In particular, we expected ‘physical functioning’ to be limited in patients with wheezing illness, RSV bronchiolitis, and burn injury. Scores for ‘growth and development’ were expected to be affected in patients with NF1 and RSV. FAC and burn injury patients were expected to report significantly lower scores on the ‘bodily pain’ scale. We expected that NF1 and FAC patients would affect the ‘temperament and moods’ scale. Due to variable disease activity over time in wheezing illness and FAC, we expected the ‘change in health’ scale score to be higher in these patients than in the reference population.

Results

The total study sample of the five health conditions included 494 children with a median age of 36 (range 0–72) months. The reference sample included 410 children with a median age of 24 (range 3–46) months. Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the patients and of the reference population. The RSV bronchiolitis subgroup was substantially younger (median 2 months of age) than the reference population (median 24 months of age); children in the other four health conditions were older than the reference population.

Table 1.

General characteristic of children and parents

| Subgroup | N | % female | Age child in months | % Female respondents | Median age respondent in years (25–75th percentile) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (25th and 75th percentile) | Range | |||||

| Reference population | 410 | 50 | 24 (13–35) | 3–46 | 97 | 33 (30–35) |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 34 | 44 | 54 (28–61) | 12–72 | 88 | 35 (30–39) |

| Wheezing illness | 138 | 41 | 35 (20–48) | 5–65 | 88 | 34 (30–37) |

| RSV infection | 47 | 55 | 2 (1–9) | 1–36 | 81 | 31 (27–35) |

| Functional abdominal complaints | 81 | 48 | 46 (27–59) | 5–72 | 88 | 35 (32–38) |

| Burn injury | 194 | 47 | 36 (28–46) | 5–63 | 77 | 34 (30–37) |

| All diseases | 494 | 46 | 36 (22–49) | 1–72 | 83 | 34 (30–37) |

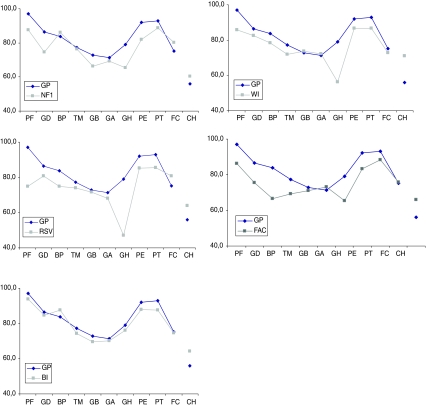

Results on the ITQOL scales are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 2. Figure 1 presents an illustration of the health profiles (as measured by the ITQOL) across all health conditions and for the reference sample. All patients with the health conditions scored significantly lower on several (different) ITQOL scales. Except for the burn injury patients, all other health conditions had lowest scores on the ‘general health perception’ scale. We observed a large range of scale scores for ‘physical functioning’, ‘bodily pain’, and ‘general health perceptions’, with moderate to large effect sizes compared to the reference sample. Parents of children with RSV reported the lowest scores for ‘physical functioning’ and ‘general health perceptions’, and parents of children with FAC reported the lowest scores for ‘bodily pain’.

Fig. 1.

ITQOL scale scores for the general population sample versus individual clinical subgroups. GP general population, NF1 neurofibromatosis type 1, WI wheezing illness, RSV RSV bronchiolitis, FAC functional abdominal complaints, BI burn injury. X-axis categories: PF physical functioning, GD growth and development, BP bodily pain, TM temperament and moods, GB general behavior, GA getting along, GH general health, PE parental emotional impact, PT parental time impact, FC family cohesion, CH change in health

Table 2.

ITQOL scale scores (SD) for general population and five clinical conditions

| ITQOL scale scores | General population N = 410 | NF type 1 N = 34 | Wheezing illness N = 138 | RSV bronchiolitis N = 47 | Functional abdominal complaints N = 81 | Burn injury N = 194 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning (PF) | 97.1 (9.8) | 87.6 (20.6)§ | 85.9 (21.1)§ | 75.0 (30.6)♦ | 86.3 (16.6)§ | 93.7 (18.2) |

| Growth and development (GD) | 86.5 (10.6) | 74.7 (18.3)§ | 82.6 (13.3) * | 80.9 (18.3) | 75.4 (13.2)♦ | 84.7 (12.5) |

| Bodily pain (BP) | 83.8 (16.8) | 86.0 (15.9) | 78.5 (18.6) * | 74.8 (26.6) * | 66.6 (23.6)♦ | 87.5 (17.1) |

| Temperament and moods (TM) | 77.2 (10.5) | 76.2 (12.1) | 72.0 (12.9) * | 73.9 (15.9) | 69.2 (12.7)♦ | 74.3 (13.0) |

| General Behavior (GB) | 72.8 (12.7) | 66.3 (20.1) | 73.7 (14.0) | 71.6 (15.0) | 71.0 (14.0) | 69.5 (15.9) |

| Getting along (GA) | 68.9 (8.0) | 69.3 (14.9) | 72.3 (9.8) | 68.0 (13.5) | 73.0 (9.0) | 70.2 (11.1) |

| General health perceptions (GH) | 79.0 (14.5) | 65.5 (16.5)♦ | 56.2 (19.2)♦ | 47.1 (21.6)♦ | 65.5 (18.8)♦ | 76.1 (16.0) |

| Parental emotional impact (PE) | 92.1 (10.5) | 81.9 (19.0)§ | 86.6 (13.8)* | 85.3 (17.3)* | 83.3 (15.7)§ | 87.9 (15.5)* |

| Parental time impact (PT) | 93.0 (11.0) | 88.9 (15.3) | 86.8 (17.7)* | 85.5 (21.0)* | 88.4 (15.5) | 87.5 (19.4)* |

| Family cohesion (FC)# | 75.3 (18.8) | 80.1 (22.1) | 72.9 (21.2) | 80.9 (17.4) | 75.9 (21.7) | 74.6 (20.9) |

| Change in health (CH)# | 56.1 (18.4) | 60.3 (23.1) | 70.9 (23.8)§ | 64.0 (27.1) | 66.0 (25.9) * | 64.2 (22.7) * |

* Small ES d ≤ 0.5; § moderate ES 0.5 ≤ d< 0.8; ♦ large ES d ≥ 0.8; only presented for significant differences compared to reference values, P ≤ 0.05; # single-item scale

Across the five health conditions, the ‘parental emotional impact’ scale scores were similar, but significantly lower than the reference values. The same observation was noted for the five subgroups on the ‘parental time impact’ scale (with 3 health conditions scoring significantly lower than the reference population). Effect sizes on these scales were small to moderate with a maximum effect size of 0.8 for the NF1 subgroup on the ‘parental emotional impact’ scale. No significant differences in scores on ‘temperament and moods’, ‘general behavior’, ‘getting along’, and ‘family cohesion’ scales were observed between the five health conditions or compared to the reference sample. Parents reported higher scores for the ‘change in health’ item in their children with wheezing illness (effect size 0.7), FAC (effect size 0.4), and burn injury (effect size 0.4) compared to the reference sample. A higher score on ‘change in health’ should be interpreted as a perceived better health of the patient compared with the previous year.

Table 3 presents the results of the children’s characteristics on the ITQOL scale scores in addition to the effects of the health conditions. The coefficients indicate the change in scale score (ranging from 0 to 100) by the presence of the characteristic compared to its absence. We observed positive effects of the child’s age on scores for ‘bodily pain’, to be interpreted as ‘older children reported higher scores than younger ones’, and negative effects for ‘family cohesion’. Parents of girls reported higher scores than parents of boys on the scales ‘general behavior’ and ‘getting along’. The observed effects of age and gender, however, are much smaller than the observed differences between the various health conditions and reference values. In addition, effect sizes were constant for all health conditions and the reference population.

Table 3.

Independent influence of child age and gender on ITQOL scale scores

| ITQOL scale* | Age of child (months) coefficient (P value)§ | Female child coefficient (P value)§ |

|---|---|---|

| Bodily pain | 0.1 (<0.01) | |

| General behavior | 2.1 (0.05) | |

| Getting along | 1.6 (0.02) | |

| Family cohesion | −0.2 (<0.01) |

* Only significantly affected scales are presented

§Value of coefficient reflects the change in domain score by presence of the variable corrected for the effect of the clinical condition, i.e. reported scores for bodily pain increased with 0.1 points per child’s month, reported mean scores for general behavior were 2.1 points higher in girls

Discussion

As expected, a lower HRQoL was reported for the 494 patients with five different somatic health conditions compared to the general population sample. The number of affected domains of HRQoL and the magnitude of effects differed between conditions. Lowest scores were obtained for the scale ‘general health perceptions’. A large range in scale scores was observed for ‘physical functioning’, ‘bodily pain’, and ‘general health perceptions’. Scale scores observed for ‘temperament and moods’, ‘general behavior’, ‘getting along’, and ‘family cohesion’ were similar across all five health conditions and to the reference population. Scales reflecting impact on the parents were equally affected by all five health conditions, albeit with mild to moderate effect sizes. In addition to the health condition, ITQOL scale scores were sensitive to the child’s age and gender.

Due to the observed low scores on the scale ‘general health perceptions’ in the majority of health conditions (with large effect sizes), we conclude that this scale is particularly sensitive to the diseases under study. The large dispersion of scores on the ‘physical functioning’, ‘bodily pain’, and ‘general health perceptions’ scales may be explained by the characteristics of the different health conditions. The scales ‘physical functioning’ and ‘general health perceptions’ are mostly affected in the RSV bronchiolitis subgroup, compared to both the general population sample and to the other health conditions. This observation fits the characteristics of RSV bronchiolitis, which is experienced as a very distressing and potentially life-threatening clinical condition [17]. It is not explained by a high frequency of prematurity or co-morbidity as their incidence was low in our RSV population. After RSV infection, the type of persistent complaints (wheezing) may have a substantial influence on these domains, as indicated by the low scores on these scales in the wheezing population. The lowest score for ‘bodily pain’ in the FAC group (large effect size) is consistent with our expectations, as pain is the main characteristic of this health condition. The present study confirms the multiple effects of wheezing illness and FAC on various aspects of HRQoL, as reported earlier [18, 23]: the parents of children with these two conditions reported most ITQOL scales to be affected, i.e. 8 and 7, respectively, out of 11 scales (with moderate to large effect sizes).

The absence of detected differences for ‘temperament and moods’, ‘general behavior’, and ‘getting along’ scores across the five health conditions and compared to the reference population may indicate that these domains are not affected by the five (somatic) health conditions. Studies in populations with attention, temperament, or other mental health problems may provide extra insight into the sensitivity of the ITQOL mental domains. The fact that nowadays general populations have more psychosocial than physical problems may explain the relatively low reference values for the mental scales. Also, due to the young age of the children in the present study, their involvement in behavior and social relationships are expected to be small. As these mental scales are included in other generic measures for infants [24] and older children [25], their presence in the ITQOL may have value for broader comparison.

The ITQOL questionnaire includes two scales reflecting the impact of the child’s disease on the parents themselves, i.e. ‘parental time impact’ and ‘parental emotional impact’. The two parental impact scales were affected similarly by all clinical subgroups, with small to moderate effect sizes compared to the reference population. These results may indicate that having a child with a disease affects parental quality of life regardless of the disease type. The large and variable impact of disease on the ‘general health perception’ scale contrasts with the smaller and homogenous impact on parental scales and may be a result of parental coping behavior. These results underline the importance of including the parental impact in HRQoL questionnaires for children. In contrast to the parental impact and to other studies [26–28], the scale ‘family cohesion’ was not affected by any of the health conditions. Because the influence on family life may only emerge after an extended period of illness of the child, this may not have been apparent in this study examining very young children.

Parents of patients with wheezing illness, FAC, and burn injuries reported a significant improvement for ‘change in health’. Since wheezing illness and FAC are chronic conditions in which health status might vary, improved scores over a period of 1 year can be anticipated. Significant increase in ‘change in health’ score for burn injury patients may reflect the recovery made between the time of admission and completing the questionnaire.

The sensitivity of ITQOL domain scores to age and gender, in addition to the effects of the health conditions, underline the importance of including age and gender in the assessment of health status and related differences in scores. Since effects of age and gender were constant for all health conditions under study, they could not account for all the differences between the health conditions and the reference population sample.

Some limitations of this study should be addressed. First, the selection of health conditions was based on the availability of studies and does not include conditions mainly characterized by physical limitations, intensive medical treatment (in hospital), or mental problems. Comparing the present results with data from children with rheumatoid, oncologic conditions, or behavior problems may provide additional information. The health conditions included here reflect various disease courses (acute/chronic/with exacerbations) and symptoms (pain, respiratory signs, skin deformities, developmental problems) and may therefore be generalizable to other disease populations. Second, the time of completing the questionnaire varied among the health conditions. Parents of the RSV children completed the questionnaire in the 2–6 months after hospitalization, reflecting mainly acute effects of RSV bronchiolitis on HRQoL. For example, we expected but did not find a significantly lower ‘growth and development’ scale score for this specific clinical subgroup. In contrast, parents of burn injury patients completed the ITQOL questionnaire (mean) 17.5 months after admission. This fact, and the limited percentage of total body surface area burned (mean 6%), may explain the relatively high scale scores for burn injury patients on most ITQOL domains. Third, the variation in time span during the recruitment of participants hampers a truly cross-sectional comparison. However, we believe that differential environment and history effects will not be substantial in a time span of 8 years. Fourth, there was considerable variation in the size of the five health condition samples. Due to the small numbers in the NF1 and RSV bronchiolitis subgroups, it may have been impossible to detect some effects of these conditions on HRQoL. The ‘change in health’ item is only applicable for children aged 1 year or older; because the RSV bronchiolitis group had few children aged 1 year or older, no firm conclusions for RSV on this item. Fifth, there was a variation in response rate between the included studies. However, a comparison of responders and non-responders did not reveal any substantial source for bias of results [7, 8, 10, 11]. Sixth, using convenience samples of health conditions there was a variety of age between the included populations. However, no disease-related differences were found for age. Seventh, in the present study we investigated the effect of different diseases and their courses on HRQoL, but did not incorporate factors such as severity of disease in this analysis. Influence of demographic characteristics such as education level has been reported by two of the included studies [7, 8]. Assessing the impact of severity, as well as other disease-related and demographic characteristics, on HRQoL would be of additional value but is beyond the scope of this study. Finally, because this study aimed to evaluate the responsiveness of the ITQOL to a variety of health conditions, we do not discuss the quality of life for each health condition separately but refer to previous publications [7, 8, 10, 11].

In conclusion, the present study has shown that the five somatic health conditions exert a substantial and negative effect on HRQoL as measured by the ITQOL. The magnitude of effect on ITQOL scores and the type of affected ITQOL domains vary depending on the type of health condition. The domains ‘physical functioning’, ‘bodily pain’, and ‘general health perceptions’ were most variably affected. Parental impact scales were equally affected by all conditions. In addition to the health condition, age and gender of the child independently affect ITQOL scores. These data on the ITQOL’s sensitivity to health conditions with different symptom expression may help in the interpretation of HRQoL results in future applications.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- BI

Burn injury

- GP

General population sample

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- ITQOL

Infant/Toddler quality of life questionnaire

- NF1

Neurofibromatosis type 1

- FAC

Functional abdominal complaints

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- WI

Wheezing illness

References

- 1.WH Organization . International classification of impairments, disabilities, and handicaps. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raat H, Mohangoo AD, Grootenhuis MA. Pediatric health-related quality of life questionnaires in clinical trials. Current opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2006;6:180–185. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000225157.67897.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiser C, Jenney M. Measuring quality of life. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2007;92:348–350. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.086405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klassen AF, Landgraf JM, Lee SK, Barer M, Raina P, Chan HPW, et al. Health related quality of life in 3 and 4 year old children and their parents: Preliminary findings about a new questionnaire. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2003;1:81. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CHQ HA. (2008). Confidential scoring rules Infant toddler quality of life questionnaire-97 (ITQOL-97). Boston, MA.

- 6.Raat H, Landgraf JM, Oostenbrink R, Moll HA, Essink-Bot ML. Reliability and validity of the Infant and Toddler quality of life questionnaire (ITQOL) in a general population- and respiratory disease sample. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:445–460. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9134-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oostenbrink R, Spong K, de Goede-Bolder A, Landgraf J. M, Raat H, Moll H. A. (2007). Parental reports of health-related quality of life in young children with neurofibromatosis type 1: Influence of condition specific determinants. Journals in pediatrics, 151(182–6), 6 e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Oostenbrink R, Jansingh-Piepers EM, Raat H, Nuijsink M, Landgraf JM, Essink-Bot ML, et al. Health-related quality of life of pre-school children with wheezing illness. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2006;41:993–1000. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rietveld E, Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Huysman MW, de Groot R, Moll HA, et al. Hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children: Development of a clinical prediction rule. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2006;25:201–207. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000202135.24485.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oostenbrink R, Jongman H, Landgraf JM, Raat H, Moll HA. Functional abdominal complaints in pre-school children: Parental reports of health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9583-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Baar ME, Essink-Bot ML, Oen IM, Dokter J, Boxma H, Hinson MI, et al. Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the American Burn Association/Shriners Hospital for Children Burn Outcomes Questionnaire (5–18 years of age) Journal of burn care & research. 2006;27:790–802. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000245434.76697.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferner RE, Huson SM, Thomas N, Moss C, Willshaw H, Evans DG, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of individuals with neurofibromatosis 1. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2007;44:81–88. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.045906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noll RB, Reiter-Purtill J, Moore BD, Schorry EK, Lovell AM, Vannatta K, et al. Social, emotional, and behavioral functioning of children with NF1. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2007;143A:2261–2273. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graf A, Landolt MA, Mori AC, Boltshauser E. Quality of life and psychological adjustment in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;149:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez FD, Helms PJ. Types of asthma and wheezing. European Respiratory Journal. 1998;12:3s–8s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyth RL, Openshaw PJ. Bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2006;368:312–322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bont L, Steijn M, van Aalderen WM, Kimpen JL. Impact of wheezing after respiratory syncytial virus infection on health-related quality of life. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2004;23:414–417. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000122604.32137.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loening-Baucke V. Prevalence, symptoms and outcome of constipation in infants and toddlers. Journals in pediatrics. 2005;146:359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyman PE, Milla PJ, Benninga MA, Davidson GP, Fleisher DF, Taminiau J. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: Neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1519–1526. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, Guiraldes E, Hyams JS, Staiano A, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: Child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1527–1537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landolt MA, Grubenmann S, Meuli M. Family impact greatest: Predictors of quality of life and psychological adjustment in pediatric burn survivors. Journal of Trauma. 2002;53:1146–1151. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varni JW, Lane MM, Burwinkle TM, Fontaine EN, Youssef NN, Schwimmer JB, et al. Health-related quality of life in pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A comparative analysis. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27:451–458. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200612000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fekkes M, Theunissen NCM, Brugman E, Veen S, Verrips EGH, Koopman HM, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the TAPQOL: A health-related quality of life instrument for 1–5 year-old children. Quality of Life Research. 2000;9:961–972. doi: 10.1023/A:1008981603178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raat H, Landgraf JM, Bonsel GJ, Gemke RJ, Essink-Bot ML. Reliability and validity of the child health questionnaire-child form (CHQ-CF87) in a Dutch adolescent population. Quality of Life Research. 2002;11:575–581. doi: 10.1023/A:1016393311799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raina P, O’Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, et al. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e626–e636. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reiter-Purtill J, Schorry EK, Lovell AM, Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA, Noll RB. Parental distress, family functioning, and social support in families with and without a child with neurofibromatosis 1. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:422–434. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taanila A, Jarvelin MR, Kokkonen J. Cohesion and parents’ social relations in families with a child with disability or chronic illness. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 1999;22:101–109. doi: 10.1097/00004356-199906000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]