Abstract

We assessed the relationship between consensus clinical diagnostic classification and neurochemical positron emission tomography imaging of striatal vesicular monoamine transporters and cerebrocortical deposition of aβ-amyloid in mild dementia. Seventy-five subjects with mild dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination score ≥ 18) underwent a conventional clinical evaluation followed by 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine positron emission tomography imaging of striatal vesicular monoamine transporters and 11C-Pittsburgh compound-B positron emission tomography imaging of cerebrocortical aβ-amyloid deposition. Clinical classifications were assigned by consensus of an experienced clinician panel. Neuroimaging classifications were assigned as Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies on the basis of the combined 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine and 11C-Pittsburgh compound-B results. Thirty-six subjects were classified clinically as having Alzheimer’s disease, 25 as having frontotemporal dementia and 14 as having dementia with Lewy bodies. Forty-seven subjects were classified by positron emission tomography neuroimaging as having Alzheimer’s disease, 15 as having dementia with Lewy bodies and 13 as having frontotemporal dementia. There was only moderate agreement between clinical consensus and neuroimaging classifications across all dementia subtypes, with discordant classifications in ∼35% of subjects (Cohen’s κ = 0.39). Discordant classifications were least frequent in clinical consensus Alzheimer’s disease (17%), followed by dementia with Lewy bodies (29%) and were most common in frontotemporal dementia (64%). Accurate clinical classification of mild neurodegenerative dementia is challenging. Though additional post-mortem correlations are required, positron emission tomography imaging likely distinguishes subgroups corresponding to neurochemically defined pathologies. Use of these positron emission tomography imaging methods may augment clinical classifications and allow selection of more uniform subject groups in disease-modifying therapeutic trials and other prospective research involving subjects in the early stages of dementia.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, amyloid, dopamine, diagnosis

Introduction

Neurodegenerative dementia is common in people over the age of 65 years, with exponential increases in prevalence associated with further ageing (Kukull and Bowen, 2002). Three clinicopathological entities constitute the great majority of neurodegenerative dementias: Alzheimer’s disease; frontotemporal dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. While Alzheimer’s disease is the most common, constituting perhaps 50–60% of dementias, prevalence of the latter two dementias is substantial. Lewy body dementia is estimated to account for 10–15% of dementias, and frontotemporal dementia accounts for ∼5% (Stevens et al., 2002; Rahkonen et al., 2003). The costs associated with dementia are substantial and expected to increase considerably over the next several decades (Sloane et al., 2002).

The clinical syndromes associated with pathologically distinct neurodegenerations have led to specific clinical diagnostic criteria, but the accuracy of clinical criteria is limited in comparison with pathological assessment (Knopman et al., 2001). Clinical differentiation of Lewy body dementia from Alzheimer’s disease is challenging. The core clinical features of Lewy body dementia (cognitive fluctuation, spontaneous visual hallucinations and parkinsonism) are not universal in Lewy body dementia, limiting diagnostic sensitivity (Tiraboschi et al., 2006). Some of these features may occur in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, limiting specificity (Tsuang et al., 2006). Differentiating frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease is similarly difficult. Clinical syndromes commonly associated with frontotemporal dementia pathology, such as primary progressive aphasia, are sometimes associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Alladi et al., 2007). Clinical criteria for frontotemporal dementia diagnosis have relatively low sensitivity, particularly early in the course of illness, and differentiation of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease demonstrates variable specificity (Lopez et al., 1999; Varma et al., 1999; Piguet et al., 2009).

Molecular neurochemical imaging with PET may be useful in differentiating dementia syndromes (Herholz et al., 2007). Severely decreased nigrostriatal terminal markers are characteristic of Lewy body dementia, and quantification of nigrostriatal terminals differentiates Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia accurately (McKeith et al., 2007). A further recent imaging development is the advent of ligands binding to cerebral aβ-amyloid deposits, including the thioflavin derivative ligand 11C-Pittsburgh compound-B (PiB; Klunk et al., 2004). Cerebral PiB binding is increased in Alzheimer’s disease, in a subset of subjects with Lewy body dementia, in some subjects with mild cognitive impairment and in some cognitively normal elderly subjects (Villemagne et al., 2008; Brooks, 2009). Subjects with mild cognitive impairment with increased PiB retention have significantly greater risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia, suggesting that amyloid deposition precedes neurological impairment in Alzheimer’s disease (Pike et al., 2007; Okello et al., 2009).

Neurochemical PET imaging may have a role in identifying underlying pathological patterns in subjects with mild dementia where clinical classification may be particularly difficult. We examined classification of subjects with mild dementia by consensus expert clinical diagnoses in comparison with their neurochemical classification on the basis of PET imaging of striatal dopaminergic innervation and cerebrocortical amyloid deposition.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 75 subjects with primary symptoms of mild dementia were recruited from the University of Michigan Cognitive Disorders Clinic. Patients with primary neurological presentations involving non-cognitive domains (ataxia, parkinsonism, etc.) are not regularly evaluated in this clinic and were not included. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to capture subjects with mildly symptomatic neurodegenerative dementias. All subjects who met these criteria and agreed to participate were entered into the study. Virtually all potential subjects with mild dementia seen in the University of Michigan Cognitive Disorders Clinic were approached about study participation by their treating clinicians during the active enrolment period. Of subjects meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria, <5% declined participation. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and where appropriate, also from subjects’ nearest relatives or legal representatives. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan (IRBMED) approved this investigation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included subjects were over the age of 40 years, had Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination scores ≥18, had cognitive symptoms for longer than 9 months and were capable of completing neuropsychological testing and research neuroimaging. Subjects with a modified Hachinski scale score >4 or meeting NINDS-AIREN (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Association Internationale pour la Recherché et l'Enseignement en Neurosciences) criteria suggesting vascular dementia were excluded (Roman, 1993; Moroney et al., 1997). Subjects were also excluded if a finding suggested a possible non-neurodegenerative cause of cognitive decline: clinically significant abnormality on screening blood tests including vitamin B12 level and thyroid function tests; Geriatric Depression Score >6; history of seizure disorder; history of cranial radiation therapy; history of mental retardation; recent history of focal brain injury; focal neurological deficits that developed simultaneously with cognitive complaints; the presence of a systemic or medical illness that would confound the diagnosis of a degenerative dementia; or consensus classification as mild cognitive impairment.

Clinical classification

Clinical evaluations included history and neurological examination, brain MRI, laboratory evaluation to exclude potential confounders and a standardized neuropsychological evaluation. The neuropsychological evaluation administered to all subjects included the measures from the National Alzheimer Coordinating Centre Unified dataset, consisting of: the Mini-Mental State Examination; Boston Naming Test; Digit Span Forwards and Backwards; Trail Making Test (Parts A and B); Logical Memory and Logical Memory-Delayed Recall; and Semantic Fluency (Animal Naming). Caregivers completed the Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Clinical, structural imaging, laboratory and neuropsychological data for each subject were abstracted into a standard form by one of the investigators (J.F.B.). A panel of experienced clinicians blinded to the PET neuroimaging (R.L.A., K.A.F., B.G.) reviewed these data and assigned a classification to each subject with reference to recommended clinical criteria for Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body dementia diagnoses (McKhann et al., 1984, 2001; McKeith et al., 2005). If there was discrepancy between the raters, consensus was reached by discussion. Consensus panel classifications were assigned without knowledge of apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE4) results.

Positron emission tomography imaging

Subjects underwent 11C-PiB and 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine PET imaging on a Siemens ECAT HR+ camera operated in 3D mode (septa retracted). The two radiotracer scans were usually performed on the same half day, with at least 2 h between scans to allow for physical decay of the first tracer prior to the second scan. 11C-PiB was administered as an intravenous bolus of 45% of the total mass dosage over 30 s followed by constant infusion of the remaining 55% of the dose over the 80-min study duration (Koeppe and Frey, 2008). 11C-PiB PET images were acquired as a dynamic series of 17 scan frames over a total of 80 min as follows: 4 × 30 s; 3 × 1 min; 2 × 2.5 min; 2 × 5 min; and 6 × 10 min. Parametric PiB distribution volume ratio (DVR) images were computed by averaging the last four scan frames (40–80 min) normalized to the mean value in the cerebellar hemisphere cortical grey matter. (+)-11C-dihydrotetrabenazine was administered intravenously as a bolus containing 55% of the total mass dose over 30 s followed by continuous infusion of the remaining 45% of the dose over the 60 min study duration (Bohnen et al., 2006). A dynamic series of PET images were acquired over 60 min: 4 × 30 s; 3 × 1 min; 2 × 2.5 min; 2 × 5 min; and 4 × 10 min. Parametric dihydrotetrabenazine DVR images were computed by averaging the last three scan frames (30–60 min) and normalized to the mean value in the occipital cerebral cortex.

Positron emission tomography neuroimaging classifications

The PET image analyses used for subject classifications were made by an expert familiar with the biodistributions of the tracers in normal and relevant pathological cases (K.A.F.). Following the procedure used in the Phase III study of N-ω-fluoropropyl-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-[123I]iodophenyl)nortropane single photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of Lewy body dementia (McKeith et al., 2007), the assessments were designed to reproduce conditions that would probably be obtained if routine clinical use of these measures were implemented. For comparison purposes only, we additionally employed volume of interest-based quantitative assessments of both tracer distributions (below). Parametric DVR 11C-PiB and 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine DVR image sets for each subject PET studies were stripped of identifiers. Images were reviewed prior to consensus clinical evaluation of blinded clinical data. Neurochemical classifications were then assigned based on combined PiB and dihydrotetrabenazine results in each subject (Fig. 1). Subjects were classified as abnormal if the striatal DVR was reduced below the range of normal findings in either hemisphere by qualitative assessment of the DVR images. Cerebral 11C-PiB retention was classified as abnormal when frontal lobe cerebral cortical DVR exceeded subjacent frontal white matter values by qualitative visual inspection of the DVR images. Visual assessment of cortical PiB deposition has been found to exhibit accuracy comparable with quantitative analyses of PiB binding (Ng et al., 2007; Suotunen et al., 2010). Some subjects with Lewy body dementia had PiB deposition, while others were PiB negative. Individuals with normal dihydrotetrabenazine binding and abnormally increased PiB deposition were classified as having Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals with normal PiB and dihydrotetrabenazine scans were classified as having frontotemporal dementia. As expected, some subjects classified as frontotemporal dementia had mild dihydrotetrabenazine reductions, but not judged below the range of normal, or were considered otherwise atypical of Lewy body dementia.

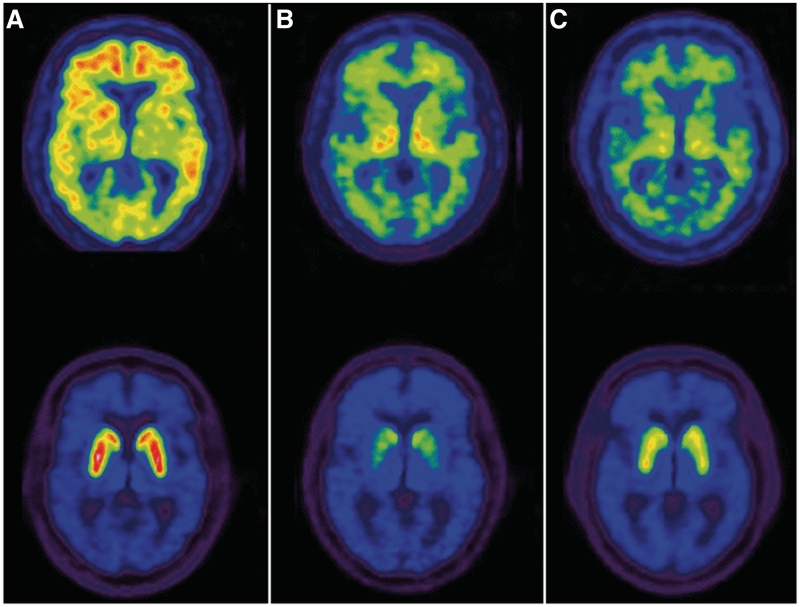

Figure 1.

Examples of PET neurochemical classifications. Shown are images depicting the equilibrium distribution volume ratio (DVR) for 11C-PiB (top) and 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine (bottom). The DVR maximum for each parametric PiB image is 3.0, while the maximum for the parametric dihydrotetrabenazine images is 4.5. (A) The subject in the first column has elevated PiB DVR in the cerebral cortex (signal exceeds subcortical white matter) and normal striatal dihydrotetrabenazine DVR, consistent with the neurochemical classification of Alzheimer’s disease. (B) The subject depicted in the middle column has normal PiB DVR (subcortical white matter exceeds cerebral cortex) and severely reduced striatal dihydrotetrabenazine binding, consistent with classification as dementia with Lewy bodies. (C) The subject in the right column has normal PiB DVR and only mildly reduced striatal dihydrotetrabenazine DVR, consistent with classification as frontotemporal dementia.

Positron emission tomography volume of interest measures

All frames of both the dihydrotetrabenazine and PiB scans were co-registered to frame 10 of the dihydrotetrabenazine scan. Parametric images were generated for both blood to brain transport rate (K1) and binding (DVR) relative to the reference tissue for each tracer (occipital cortex for dihydrotetrabenazine and cerebellar cortical grey matter for PiB). PET images for each subject were reoriented to a common coordinate system based on the stereotactic atlas of Talairach and Tournoux (1988). Following reorientation, all images underwent linear scaling and non-linear warping to minimize individual anatomical structural differences (Minoshima et al., 1994). A single transformation based on the individual’s dihydrotetrabenazine K1 images was calculated for each subject and then applied to the other three parametric image sets.

All transaxial levels of the atlas have been digitized and a set of standardized volumes of interest defined on the atlas images, including cerebrocortical Brodmann areas (BA) as well as subcortical, cerebellum, brainstem and white matter regions. In dihydrotetrabenazine quantitative analyses, volumes of interest were applied bilaterally to the putamen, and the DVR value from the hemisphere with lowest binding was used. In PiB analyses, volumes were extracted corresponding to the lateral and medial frontal cortices (BA 9–11 and 44–46) and subcortical white matter (both anteriorly and posteriorly at the level of the basal ganglia and superiorly at the level dorsal to the lateral ventricles).

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was performed with Stata version 11.1 (Stata Corp.). Demographics and other characteristics of the subjects were summarized as frequencies and percents for categorical variables, and as means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables. Differences between groups on demographic and neuropsychological variables were assessed using chi-square tests for categorical variables, t-tests or one-way ANOVA for normally distributed variables, and Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis rank sum tests for non-normally distributed variables. The κ-statistics were calculated to assess inter-assessment agreement.

Results

A total of 75 subjects were evaluated. Thirty-six subjects were classified clinically as having Alzheimer’s disease, 14 as having Lewy body dementia and 25 as having frontotemporal dementia. The mean age was 72 years (range 54–90 years) and 40% of the subjects were female (Table 1). There were few significant differences among clinically defined groups in historical or neuropsychological characteristics and these were relatively modest in magnitude. Reflecting employment of the standard clinical diagnostic criteria, the differences in historical and neuropsychological features of study subjects were predictable. Behavioural complaints were more common in clinically classified frontotemporal dementia than in clinically classified Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia, though this difference was not significant. Parkinsonism and hallucinations were more common in clinically classified Lewy body dementia than Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Clinically classified subjects with frontotemporal dementia performed worse than the other groups on the Trail Making Test Part A, though this result did not achieve significance. Logical Memory-Delayed Recall scores were lower in clinically classified Alzheimer’s disease compared with clinically classified subjects with frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body dementia, while Block Design scores were worse in clinically classified Lewy body dementia than in the other subject groups. The proportion of APOE4 heterozygotes and homozygotes were distributed approximately equally across all three groups.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics by consensus clinical classification

| AD (n = 36) | DLB (n = 14) | FTD (n = 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 8 | 69 ± 9 | 0.101 |

| Female, n (%) | 13 (36) | 5 (36) | 12 (48) | 0.606 |

| White, n (%) | 35 (94) | 12 (86) | 25 (100) | 0.191 |

| Years of education | 15 ± 3 | 14 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 0.709 |

| CDR | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.496 |

| MMSE | 23 ± 3 | 22 ± 4 | 22 ± 4 | 0.445 |

| APOE4 heterozygote, n (%) | 13 (36) | 3 (21) | 5 (20) | 0.322 |

| APOE4 homozygote, n (%) | 7 (19) | 1 (7) | 3 (12) | 0.489 |

| Historical features, n (%) | ||||

| Memory complaint | 31 (86) | 12 (86) | 19 (76) | 0.559 |

| Behavioural complaint | 5 (14) | 2 (14) | 9 (36) | 0.090 |

| Parkinsonism | 3 (8) | 11 (79) | 1 (4) | <0.001 |

| Hallucinations | 0 (0) | 8 (57) | 1 (4) | <0.001 |

| Neuropsychological indices | ||||

| Logical Memory | 5.8 ± 4.1 | 8.1 ± 4.5 | 7.3 ± 5.1 | 0.222 |

| Digit span forward | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 6.8 ± 3.2 | 5.7 ± 2.5 | 0.083 |

| Digit span backwards | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 2.2 | 3.8 ± 1.7 | 0.390 |

| Animals | 12 ± 5 | 10 ± 4 | 12 ± 5 | 0.359 |

| Trail Making Test, Part A | 63 ± 36 | 93 ± 44 | 183 ± 309 | 0.075 |

| Trail Making Test, Part B | 500 ± 386 | 480 ± 342 | 572 ± 390 | 0.820 |

| Block Design | 27 ± 12 | 17 ± 6 | 22 ± 12 | 0.017 |

| Logical Memory-Delayed Recall | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 7.2 ± 4.9 | 6.6 ± 4.6 | 0.008 |

| Boston Naming Test | 22 ± 5 | 23 ± 5 | 23 ± 6 | 0.924 |

| NPI-Q total score | 2.6 ± 2.4 | 2.6 ± 2.4 | 2.6 ± 2.2 | 0.978 |

| NPI-Q severity | 3.6 ± 4.0 | 4.5 ± 5.0 | 4.2 ± 4.1 | 0.735 |

Values represent the mean ± SD of demographic, clinical and neuropsychological characteristics, except where noted. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; CDR = clinical dementia rating scale score; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; MMSE = Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination score; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Bold values are significant at an unadjusted threshold of p < 0.05.

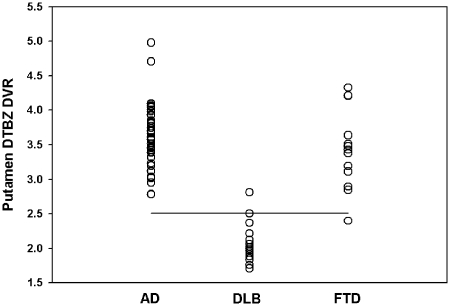

PET molecular imaging with dihydrotetrabenazine revealed 15 cases with significant striatal deficits. Of these, 10 had findings considered typical of Lewy body dementia, with relatively symmetrical side-to-side and rostrocaudal (caudate-to-putamen) reductions of DVR. Five cases demonstrated significant reductions, but had significant side-to-side asymmetry of striatal DVR. An additional five subjects had very mild abnormalities of dihydrotetrabenazine DVR that were judged borderline, but assigned within the normal range. For comparison purposes, volume of interest quantitative results revealed putamen DVR values of 3.61 ± 0.44 (mean ± SD) in subjects assigned imaging diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease, 2.07 ± 0.29 in subjects with Lewy body dementia and 3.43 ± 0.57 in subjects with frontotemporal dementia (Fig. 2). Employing a −2.5 SD threshold below the mean of the Alzheimer’s disease group, a single image-classified case with Lewy body dementia had normal-range DVR and a single image-classified case with frontotemporal dementia had reduced dihydrotetrabenazine DVR in the putamen. Retrospective review of the image-classified case with Lewy body dementia revealed a marked interhemispheric striatal DVR asymmetry, resulting in an abnormal visual inspection classification. The image-classified case with frontotemporal dementia demonstrated entirely preserved caudate nucleus DVR despite the lowest putamen DVR within the decreased range. If the former subjects were reclassified to image-based normal dihydrotetrabenazine, this subject would then be frontotemporal dementia, concordant with their consensus clinical classification. The latter subject, if reclassified to image-based abnormal dihydrotetrabenazine, would then be considered Lewy body dementia, discordant with their clinical consensus diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia.

Figure 2.

Volume-of-interest dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) binding in the putamen. DVR values for the lowest hemisphere of each subject are depicted according to the qualitative image-based subject classification. A cut-off value of 2.51 is depicted by the horizontal line, representing −2.5 SD below the mean of the subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Based on the assumption that subjects with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) may have mild dihydrotetrabenazine reduction, there may be one subject with Lewy body dementia (DLB) and one subject with FTD that could be reclassified on the basis of volume of interest quantification compared with the qualitative visual analysis (see text for detailed discussion).

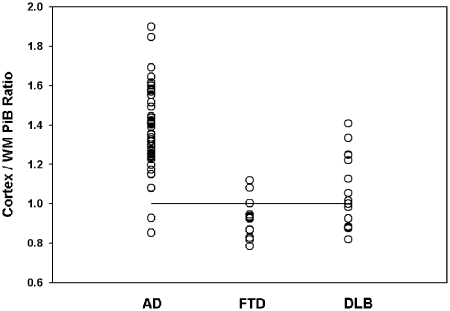

PET molecular imaging of PiB binding revealed abnormally increased frontal neocortical DVR relative to subjacent white matter in 54 subjects. There were five instances where the distinction of increased frontal cortical 11C-PiB binding was considered difficult; two cases were ultimately assigned as normal PiB imaging and three cases considered as abnormally increased PiB binding by qualitative assessment. Comparison of volume of interest-based assessment of frontal cerebral cortex to average subcortical white matter revealed a ratio of 1.38 ± 0.21 in cases with image-based classification of Alzheimer’s disease versus 0.92 ± 0.10 in cases classified as frontotemporal dementia (Fig. 3). Cases classified as Lewy body dementia had ratios in both the normal and elevated ranges, consistent with the known overlap of Lewy body pathology with aβ-amyloid pathology in Lewy body dementia. Employing a cut-off ratio of 1.0, two cases qualitatively classified as PiB ‘positive’ had values below this threshold. Review of these instances revealed some areas in the white matter with relatively elevated DVR, despite white matter values in at least one mid-frontal lobe that were at or below overlying cortical binding. Conversely, there were two subjects qualitatively classified as PiB ‘negative’ with volume of interest ratio values >1.0. Review of these cases revealed higher frontal lobe white matter DVR than overlying cortex, but with suggestion of reduced periventricular white matter PiB, likely contributing to elevation of the volume of interest ratios. If all four subjects were reclassified based on volume of interest results, two cases of concordant imaging and clinical consensus frontotemporal dementia would become discordant, image-based Alzheimer’s disease, while two cases of discordant image-based Alzheimer’s disease would become concordant frontotemporal dementia.

Figure 3.

Volume of interest PiB binding ratio of frontal cerebral cortex to subcortical white matter (WM). DVR ratios are depicted for each subject according to their qualitative image analysis-based classification. The horizontal line depicts the theoretically employed threshold of abnormality of 1.0. Based on the volume of interest threshold, there are two cases qualitatively classified as abnormal (Alzheimer’s disease) that fall below the quantitative threshold and two cases qualitatively classified as normal (frontotemporal dementia) that fall in the quantitatively abnormal range (see text for detailed discussion). AD = Alzheimer’s disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; WM = subcortical cerebral hemispheric white matter.

On the basis of the qualitative PET neurochemical image interpretations, 47 subjects were characterized as having Alzheimer’s disease, 15 as having Lewy body dementia and 13 as having frontotemporal dementia (Table 2). We also compared clinical and neuropsychological features of groups defined by their neurochemical imaging classifications (Table 2). There were modest differences of small magnitude among subject historical features, reflecting the expected differential patterns in patients with these dementias, and overall similar to the clinically defined group characteristics (Table 1). Among historical features, behavioural complaints were more common in subjects with imaging classification as frontotemporal dementia, and parkinsonism and hallucinations occurred more frequently in subjects classified as Lewy body dementia. A substantial fraction (38%), however, of subjects neurochemically classified as having frontotemporal dementia did not have prominent behavioural complaints. Similarly, a significant fraction of subjects neurochemically classified as having Lewy body dementia (47%) lacked parkinsonism, and some subjects classified neurochemically as Alzheimer’s disease had either prominent behavioural complaints or parkinsonism. Neurochemically classified patients with Alzheimer’s disease had lower scores on logical memory testing, including delayed recall. Other measures (Trail Making Test Part A; Block Design) that differed among the clinically defined groups were similar between neurochemically defined groups (Table 2). No subject classified as frontotemporal dementia by imaging criteria was an APOE4 homozygote and only a minority were APOE4 heterozygotes. While proportions of APOE4 homozygotes were not significantly different across groups, there was a trend towards enrichment of APOE4 homozygotes in subjects classified as having Alzheimer’s disease by neurochemical imaging criteria.

Table 2.

Subject characteristics by molecular imaging classification

| AD (n = 47) | DLB (n = 15) | FTD (n = 13) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 71 ± 9 | 75 ± 6 | 69 ± 9 | 0.089 |

| Female, n (%) | 23 (49) | 4 (27) | 3 (23) | 0.121 |

| White, n (%) | 45 (96) | 13 (87) | 13 (100) | 0.293 |

| Years of education | 15 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 0.957 |

| CDR | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.424 |

| MMSE | 22 ± 4 | 23 ± 4 | 23 ± 3 | 0.146 |

| APOE4 heterozygote, n (%) | 13 (28) | 5 (33) | 3 (23) | 0.831 |

| APOE4 homozygote, n (%) | 10 (21) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0.098 |

| Historical features, n (%) | ||||

| Memory complaint | 39 (83) | 12 (80) | 11 (85) | 0.945 |

| Behavioural complaint | 5 (11) | 3 (20) | 8 (62) | <0.001 |

| Parkinsonism | 5 (11) | 8 (53) | 2 (15) | 0.001 |

| Hallucinations | 1 (2) | 6 (40) | 2 (15) | <0.001 |

| Neuropsychological indices | ||||

| Logical Memory | 5.7 ± 4.5 | 8.3 ± 4.0 | 8.4 ± 4.5 | 0.040 |

| Digit span forward | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 7.2 ± 2.9 | 5.5 ± 2.1 | 0.108 |

| Digit span backwards | 4.2 ± 1.8 | 4.4 ± 2.2 | 4.2 ± 1.4 | 0.961 |

| Animals | 12 ± 5 | 9 ± 4 | 13 ± 5 | 0.121 |

| Trail Making Test, Part A | 107 ± 193 | 89 ± 44 | 134 ± 261 | 0.325 |

| Trail Making Test, Part B | 536 ± 389 | 568 ± 364 | 405 ± 345 | 0.332 |

| Block Design | 24 ± 13 | 21 ± 7 | 27 ± 10 | 0.280 |

| Logical Memory-Delayed Recall | 4.4 ± 4.0 | 6.5 ± 4.9 | 7.1 ± 4.0 | 0.050 |

| Boston Naming Test | 22 ± 6 | 24 ± 4 | 25 ± 3 | 0.255 |

| NPI-Q total score | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 2.2 | 3.5 ± 2.7 | 0.325 |

| NPI-Q severity | 3.3 ± 3.7 | 4.1 ± 4.4 | 6.2 ± 5.1 | 0.163 |

Values represent the mean ± SD of demographic, clinical and neuropsychological characteristics, except where noted. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; CDR = clinical dementia rating scale score; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; MMSE = Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination score; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Bold values are significant at an unadjusted threshold of p < 0.05.

The overall concordance between clinical and neuroimaging classifications was only moderate (Table 3). The overall κ-statistic for agreement between classifications was 0.39 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.27–0.58]. With each of the clinical classifications analysed separately (Table 4), κ for the identification of Alzheimer’s disease was 0.39 (95% CI: 0.18–0.61), for frontotemporal dementia 0.32 (95% CI: 0.11–0.52) and for Lewy body dementia 0.62 (95% CI: 0.39–0.84). Using the molecular neuroimaging classifications as the ‘gold standard’, clinical classifications of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia exhibited moderate specificities and sensitivities and clinical classification of Lewy body dementia exhibited moderate sensitivity and good specificity (Table 4).

Table 3.

Clinical versus molecular imaging subject classifications

| Neurochemical imaging classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | DLB | FTD | ||

| Clinical consensus classification | AD | 30 | 4 | 2 |

| DLB | 2 | 10 | 2 | |

| FTD | 15 | 1 | 9 | |

AD = Alzheimer’s disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia.

Table 4.

Clinical diagnostic performance relative to molecular imaging gold standard

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | κ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical classification | AD | 0.64 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.39 |

| FTD | 0.69 | 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.92 | 0.32 | |

| DLB | 0.67 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.92 | 0.62 |

AD = Alzheimer’s disease; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia.

The most frequent discordance between the clinical and molecular imaging classifications was observed in subjects classified clinically as frontotemporal dementia. Of 25 clinical subjects with frontotemporal dementia, only nine were classified as frontotemporal dementia by imaging criteria. Fifteen subjects with clinical frontotemporal dementia had positive PiB scans, leading to a molecular imaging Alzheimer’s disease classification. One subject with clinical frontotemporal dementia had a severely abnormal dihydrotetrabenazine scan, leading to a molecular imaging Lewy body dementia classification. Excluding this latter subject, clinically classified subjects with frontotemporal dementia were dichotomized on PET-PiB imaging results (positive versus negative; Table 5). There were significantly more females than males in the discordant frontotemporal dementia group (clinically classified as frontotemporal dementia and PET classified as Alzheimer’s disease). Behavioural complaints were significantly more common in the concordant frontotemporal dementia group (clinically and PET classified as frontotemporal dementia; 78% versus 13%; P < 0.05) and Neuropsychiatric Inventory total scores (3.6 versus 1.9, P < 0.05) and Neuropsychiatric Inventory severity (6.3 versus 2.8, P < 0.05) were higher in this group. The discordant frontotemporal dementia group (clinically classified as frontotemporal dementia and PET classified as Alzheimer’s disease) was compared also with those concordantly classified as Alzheimer’s disease (clinically and PET classified as Alzheimer’s disease; Table 6). Neuropsychological testing revealed significantly more impaired delayed recall in the concordant Alzheimer’s disease than discordant frontotemporal dementia (3.1 ± 3.0 versus 6.7 ± 4.7; P < 0.05) and non-significant trends towards more impaired frontal testing in the discordant frontotemporal dementia group (Animals: 13 ± 5 in Alzheimer’s disease versus 11 ± 4 in frontotemporal dementia, P = 0.22; Trail Making Test Part A: 61 ± 34 in Alzheimer’s disease versus 201 ± 325 in frontotemporal dementia, P = 0.17; and Trail Making Test Part B: 480 ± 379 in Alzheimer’s disease versus 632 ± 408 in frontotemporal dementia, P = 0.49). The discordant frontotemporal dementia group had better memory performance and a trend towards more impaired frontal function than the concordant Alzheimer’s disease group.

Table 5.

PiB-negative (concordant) versus PiB-positive (discordant) clinical consensus subjects with frontotemporal dementia

| PiB-negative (n = 9) | PiB-positive (n = 15) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 69 ± 9 | 68 ± 8 | 0.156 |

| Female, n (%) | 1 (11) | 10 (67) | 0.008 |

| White, n (%) | 9 (100) | 15 (100) | – |

| Years of education | 14 ± 4 | 16 ± 3 | 0.211 |

| CDR | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.882 |

| MMSE | 23 ± 4 | 21 ± 4 | 0.586 |

| APOE4 heterozygote, n (%) | 3 (33) | 2 (13) | 0.243 |

| APOE4 homozygote, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (20) | 0.151 |

| Historical features, n (%) | |||

| Memory complaint | 7 (78) | 11 (73) | 0.808 |

| Behavioural complaint | 7 (78) | 2 (13) | 0.002 |

| Parkinsonism | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 0.429 |

| Hallucinations | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.187 |

| Neuropsychological indices | |||

| Logical Memory | 8.1 ± 4.3 | 6.8 ± 5.8 | 0.431 |

| Digit span forward | 5.0 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 2.7 | 0.211 |

| Digit span backwards | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 0.977 |

| Animals | 13 ± 6 | 11 ± 4 | 0.493 |

| Trail Making Test, Part A | 163 ± 313 | 201 ± 326 | 0.766 |

| Trail Making Test, Part B | 500 ± 378 | 632 ± 408 | 0.835 |

| Block Design | 27 ± 10 | 19 ± 13 | 0.231 |

| Logical Memory-Delayed Recall | 7.2 ± 4.5 | 6.7 ± 4.7 | 0.753 |

| Boston Naming Test | 24 ± 4 | 22 ± 7 | 0.592 |

| NPI-Q total score | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.043 |

| NPI-Q severity | 6.3 ± 4.7 | 2.8 ± 3.0 | 0.022 |

Values represent the mean ± SD of demographic, clinical and neuropsychological characteristics, except where noted. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; CDR = clinical dementia rating scale score; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; MMSE = Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination score; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Bold values are significant at an unadjusted threshold of p < 0.05.

Table 6.

Clinical frontotemporal dementia versus clinical Alzheimer’s disease in molecular imaging classified subjects with Alzheimer’s disease

| Clinical AD (n = 30) | Clinical FTD (n = 15) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 73 ± 9 | 68 ± 8 | 0.513 |

| Female, n (%) | 12 (40) | 10 (67) | 0.092 |

| White, n (%) | 28 (93) | 15 (100) | 0.593 |

| Years of education | 15 ± 3 | 16 ± 3 | 0.284 |

| CDR | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.335 |

| MMSE | 22 ± 3 | 21 ± 4 | 0.563 |

| APOE4 heterozygote | 11 (37) | 2 (13) | 0.104 |

| APOE4 homozygote | 7 (23) | 3 (20) | 0.800 |

| Historical features, n (%) | |||

| Memory complaint | 26 (87) | 11 (73) | 0.270 |

| Behavioural complaint | 3 (10) | 2 (13) | 0.737 |

| Parkinsonism | 2 (7) | 1 (7) | > 0.999 |

| Hallucinations | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Neuropsychological indices | |||

| Logical Memory | 5.0 ± 3.6 | 6.8 ± 5.8 | 0.481 |

| Digit span forward | 7.3 ± 2.0 | 6.1 ± 2.7 | 0.202 |

| Digit span backwards | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 0.289 |

| Animals | 13 ± 5 | 11 ± 4 | 0.263 |

| Trail Making Test, part A | 61 ± 34 | 201 ± 325 | 0.174 |

| Trail Making Test, part B | 481 ± 379 | 632 ± 408 | 0.485 |

| Block Design | 27 ± 12 | 19 ± 13 | 0.101 |

| Logical Memory-Delayed Recall | 3.1 ± 3.0 | 6.7 ± 4.7 | 0.008 |

| Boston Naming Test | 22 ± 5 | 22 ± 7 | 0.754 |

| NPI-Q total score | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 0.334 |

| NPI-Q severity | 5.0 ± 3.6 | 7.2 ± 5.8 | 0.106 |

Values represent the mean ± SD of demographic, clinical and neuropsychological characteristics, except where noted. AD = Alzheimer’s disease; CDR = clinical dementia rating scale score; DLB = dementia with Lewy bodies; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; MMSE = Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination score; NPI-Q = Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Bold values are significant at an unadjusted threshold of p < 0.05.

Discussion

This study focused on differentiation of subjects with mild dementias, where clinical evaluations may have limited accuracy. Such distinctions are of increasing scientific relevance, especially in the context of emerging pathology-specific therapeutic trials requiring early intervention. We found only moderate concordance between expert consensus clinical classification and neurochemical pathology demonstrated by 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine and 11C-PiB PET imaging, with 35% of subjects receiving discordant clinical versus neuroimaging classifications. This result is not necessarily unexpected; even in subjects with well-established dementia, clinical differentiation of neurodegenerations is imprecise (Knopman et al., 2001). Clinical accuracy is variable across studies, with significant trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic classifications. Lewy body dementia consensus criteria, for example, demonstrate good specificity but relatively poor sensitivity (McKeith et al., 2000). Up to 77% of patients with autopsy-diagnosed frontotemporal dementia meet Alzheimer’s disease clinical criteria, indicating limited specificity of clinical Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis (Varma et al., 1999). Clinical criteria for diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia appear to be particularly imprecise. Mendez et al. (2007) systematically evaluated clinical criteria for diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia and ancillary imaging measures and found clinical criteria to be relatively inaccurate with sensitivity of only 37%. These investigators also reported that initial neuropsychology evaluations were relatively unhelpful in differentiating frontotemporal dementia from other dementing illnesses. Although there is evidence that accuracy of clinical diagnosis improves with serial evaluations and symptomatic progression (Jagust et al., 2007; Mendez et al., 2007), the problem of differentiating neurodegenerative dementias remains particularly challenging in symptomatically mild cases.

Among the three diagnostic categories, we found the highest degree of concordance between neurochemical imaging and clinical classifications of Lewy body dementia, and lower concordance between clinical and neurochemical imaging classifications of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. These results are roughly parallel with prior clinicopathological correlation studies of dementia diagnosis (Lopez et al., 1999; Varma et al., 1999; McKeith et al., 2000). The considerable degree of overlap in clinical features between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia degrades the performance characteristics of clinical criteria for these disorders (Lopez et al., 1999; Varma et al., 1999), while the relative specificity of the clinical criteria for Lewy body dementia improves the performance of the Lewy body dementia clinical criteria (McKeith et al., 2000).

The most frequent discrepancy in our series was in subjects classified clinically as frontotemporal dementia, where more than half had positive 11C-PiB PET scans, leading to neurochemical Alzheimer’s disease classification. Discordant subjects with frontotemporal dementia (clinical frontotemporal dementia, PET Alzheimer’s disease) exhibited better memory function, more frequent behavioural complaints and a trend towards more impaired frontal lobe function than concordant subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (clinical Alzheimer’s disease and PET Alzheimer’s disease). The discordant frontotemporal dementia group had less frequent behavioural complaints than the concordant frontotemporal dementia group; however, it was otherwise similar. Clinical features do not obviously distinguish among these subjects. This result is consistent with the experience of Mendez et al. (2007) and a recent systematic autopsy series reporting that up to 34% of subjects with focal cortical syndromes typical of frontotemporal dementias have Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Alladi et al., 2007). Our results are also qualitatively consistent with two small series reporting 11C-PiB results in clinically defined frontotemporal dementia (Rabinovici et al., 2007; Engler et al., 2008). These groups reported that 20–25% of clinically defined frontotemporal dementia exhibited positive 11C-PiB scans. Alternatively, the discrepancy between clinical and neurochemical classifications in our study could be explained by misleading PiB results. Recent series, however, reporting subjects with frontotemporal dementia with more advanced disease demonstrate no incidences of PiB positivity (Rowe et al., 2007). Our result of significant discrepancy between clinical and neurochemical imaging classification is also qualitatively consistent with the experience of a recent trial of bapineuzumab in which potential subjects with mild probable Alzheimer’s disease comparable with our subjects (Mini-Mental State Examination 18–26) were evaluated with 11C-PiB at trial entry. In that study, 8 out of 53 subjects with probable Alzheimer’s disease (15%) had low brain 11C-PiB retention and were excluded from the study (Rinne et al., 2010). Our data do not identify a simple clinical or neuropsychological distinction between molecularly defined frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, highlighting the need for imaging or other biomarkers.

There are several potential limitations of our study. Our subjects were drawn from a university-based cognitive disorders clinic, and are not a general population sample. Most likely reflecting referral bias, we enrolled a relatively high number of subjects with clinical frontotemporal dementia, and these patients were responsible for the greatest discord between neurochemical and clinical classifications. Nevertheless, the within-clinical diagnostic classification performance of expert raters in our series is likely to reflect near-optimal results of applying clinical criteria in general neurological clinics. We did not include subjects presenting with clinically important neurological deficits other than cognitive decline at symptomatic outset. Therefore, we cannot determine the ability of our imaging strategy to accurately categorize subjects with Parkinson disease with dementia, or other neurodegenerations with prominent movement disorders at or before the onset of cognitive decline. As is conventional, our clinical and imaging classifications presuppose that each subject has one type of pathology. Recent large autopsy series identify frequent co-morbid pathologies in demented subjects and some of our subjects may have more than one form of pathology contributing to their dementia. The most common form of pathological overlap is significant vascular pathology plus neurodegenerative pathology, which would not confound our classifications (Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study, 2001; White et al., 2005; Schneider et al., 2007; Sonnen et al., 2007, 2010; Schneider and Bennett, 2010). Co-morbid Alzheimer’s disease pathology and Lewy body dementia, however, are described well and some of our subjects could have both Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia (Schneider et al., 2007; Sonnen et al., 2010). In these studies, overlap of frontotemporal dementia and other neurodegenerative pathologies is not described. This may reflect an actual biological difference or may be an artefact of the still-evolving methods and criteria for pathological evaluation of frontotemporal dementia (Mackenzie et al., 2009).

The accuracy of 11C-PiB PET in our neuroimaging classification scheme may not be infallible. There is, however, prior evidence that 11C-PiB imaging detects only fibrillar aβ-amyloid deposits, and not aggregates of tau or α-synuclein (Klunk et al., 2003; Fodero-Tavoletti et al., 2007). Prior post-mortem studies indicate that substantial loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic terminals is relatively specific to Lewy body dementia, at least as compared with Alzheimer’s disease (Piggott et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 2002). Cerebral amyloid deposition, as determined by PiB imaging, is a surprisingly common finding in older individuals, as many as 20% of cognitively normal individuals in some studies (Villemagne et al., 2008). Some patients with frontotemporal dementia may have coincidental amyloid deposition and would be classified as Alzheimer’s disease in our classification scheme.

Our primary study design employed qualitative visual classifications of PiB and dihydrotetrabenazine parametric distribution volume images in a fashion likely to emulate future diagnostic imaging approaches. Overall, there was excellent agreement between observer image classification and quantitative volume of interest-based measures. In PiB data, visual and quantitative criteria agreed in 56 of 60 cases (the 15 subjects with image-based Lewy body dementia classification did not contribute to this distinction, since they may be either amyloid-positive or -negative). In dihydrotetrabenazine data, there was complete agreement between visual and quantitative criteria for establishing lack of a significant nigrostriatal lesion (image-based Alzheimer’s disease classification). Two of 28 subjects classified as image-based Lewy body dementia or frontotemporal dementia demonstrated discrepant visual versus quantitative classifications. Overall, the potential for misclassification by neuroimaging cannot be discounted, but would appear to contribute only a minor source of error in our present series. The performance characteristics of 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine binding are not reported previously in mild dementia. False positives among normal subjects are unlikely to present a significant problem for 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine imaging as there is wide separation between binding in normal controls and in subjects with Lewy body dementia (Bohnen et al., 2006; Koeppe et al., 2008). Our designation of subjects with abnormal 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine binding as Lewy body dementia, however, could lead to misclassification of some subjects with frontotemporal dementia. Some subjects with clinically defined frontotemporal dementia may exhibit significant nigrostriatal degeneration, potentially confounding the differentiation of Lewy body dementia from frontotemporal dementia (Rinne et al., 2002). In our series, this appears relatively unlikely, as only one subject clinically classified with frontotemporal dementia had an abnormal 11C-dihydrotetrabenazine result. In a prior PET study of striatal dopaminergic innervation in advanced, clinically defined frontotemporal dementia, the average reduction from the control mean was ∼20%, although 2 of 12 subjects had relatively severe reductions (Rinne et al., 2002). It remains to be established whether these latter subjects have pathologically confirmed frontotemporal dementia or Lewy body dementia.

There is significant potential clinical and research impact in distinguishing neurodegenerative dementias. Effective treatments can be more accurately directed to those who may benefit, such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia while potentially harmful treatments can be avoided, such as neuroleptics in Lewy body dementia or acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in frontotemporal dementia. An effective non-invasive mechanism for differentiating neurodegenerative dementias, particularly early in the disease course, would have significant utility in clinical trials where treatments are directed at specific neurochemical pathophysiologies (Thal et al., 2006). Although the PET neurochemical imaging approach employed in our study requires further evaluation with autopsy confirmation, it has potential to augment clinical classifications significantly. If this approach is validated, it could then be used as a proxy to evaluate more convenient diagnostic biomarkers. Until prospective confirmation of the PET approach is available, interventional research protocols focusing on subjects with concordant clinical and imaging phenotypes would be the conservative approach.

Funding

United States National Institutes of Health (grant P50 AG008671 to R.L.A., K.A.F., B.G., S.G.; grant P01 NS015655 to R.L.A., K.A.F., R.A.K., M.R.K., S.G.).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Brain editors and anonymous reviewers for constructive criticism.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APOE4

apolipoprotein ε 4 allele

- DVR

distribution volume ratio

- PiB

Pittsburgh compound B

References

- Alladi S, Xuereb J, Bak T, Nestor P, Knibb J, Patterson K, et al. Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:2636–45. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnen NI, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Wernette K, Kilbourn MR, Minoshima S, et al. Positron emission tomography of monoaminergic vesicular binding in aging and Parkinson disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1198–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DJ. Imaging amyloid in Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies with positron emission tomography. Mov Dis. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S742–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.22581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler H, Santillo AF, Wang SX, Lindau M, Savitcheva I, Nordberg A, et al. In vivo amyloid imaging with PET in frontotemporal dementia. Eur J Nuc Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:100–6. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Smith DP, McLean CA, Adlard PA, Barnham KJ, Foster LE, et al. In vitro characterization of Pittsburgh compound-B binding to Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10365–71. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0630-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K, Carter SF, Jones M. Positron emission tomography imaging in dementia. Br J Radiol. 2007;80(Spec 2):s160–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr/97295129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagust W, Reed B, Mungas D, Ellis W, Decarli C. What does fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging add to a clinical diagnosis of dementia? Neurology. 2007;69:871–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269790.05105.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, Wang Y, Blomqvist G, Holt DP, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, Wang Y, Huang GF, Debnath ML, Holt DP, Shao L, et al. The binding of 2-(4-methylaminophenyl)benzothiazole to postmortem brain homogenates is dominated by the amyloid component. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2086–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02086.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, Chui H, Corey-Bloom J, Relkin N, et al. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1143–53. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppe RA, Frey KA. Equilibrium analysis of [11C]PIB studies. NeuroImage. 2008;41:T30. [Google Scholar]

- Koeppe RA, Gilman S, Junck L, Wernette K, Frey KA. Differentiating Alzheimer’s disease from dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson's disease with (+)-[11C]dihydrotetrabenazine positron emission tomography. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:s67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukull WA, Bowen JD. Dementia epidemiology. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:573–90. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(02)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Litvan I, Catt KE, Stowe R, Klunk W, Kaufer DI, et al. Accuracy of four clinical diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of neurodegenerative dementias. Neurology. 1999;53:1292–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Alafuzoff I, Kril J, et al. Nomenclature for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:15–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Ballard CG, Perry RH, Ince PG, O’Brien JT, Neill D, et al. Prospective validation of consensus criteria for the diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2000;54:1050–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeith I, O’Brien J, Walker Z, Tatsch K, Booij J, Darcourt J, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of dopamine transporter imaging with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies: a phase III, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:305–13. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1803–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services task force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez MF, Shapira JS, McMurtray A, Licht E, Miller BL. Accuracy of the clinical evaluation for frontotemporal dementia. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:830–5. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.6.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minoshima S, Koeppe RA, Frey KA, Kuhl DE. Anatomic standardization: linear scaling and nonlinear warping of functional brain images. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:1528–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroney JT, Bagiella E, Desmond DW, Hachinski VC, Mölsä PK, Gustafson L, et al. Meta-analysis of the Hachinski ischemic score in pathologically verified dementias. Neurology. 1997;49:1096–105. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.4.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study (MRC CFAS) Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Lancet. 2001;357:169–75. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03589-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S, Villemagne VL, Berlangieri S, Lee ST, Cherk M, Gong SJ, et al. Visual assessment versus quantitative assessment of 11 C-PIB PET and 18 F-FDG PET for detection of Alzheimer's disease. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:547–52. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.037762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, Archer HA, Turkheimer FE, Någren K, et al. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years: an 11C-PIB PET study. Neurology. 2009;73:754–60. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b23564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggott MA, Marshall EF, Thomas N, Lloyd S, Court JA, Jaros E, et al. Striatal dopaminergic markers in dementia with Lewy bodies, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: rostrocaudal distribution. Brain. 1999;122:1449–68. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.8.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet O, Hornberger M, Shelley BP, Kipps CM, Hodges JR. Sensitivity of current criteria for the diagnosis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2009;72:732–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343004.98599.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike KE, Savage G, Villemagne VL, Ng S, Moss SA, Maruff P, et al. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2007;130:2837–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici GD, Furst AJ, O’Neil JP, Racine CA, Mormino EC, Baker SL, et al. 11C-PIB PET imaging in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2007;68:1205–12. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259035.98480.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahkonen T, Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Rissanen S, Vatanen A, Viramo P, Sulkava R. Dementia with Lewy bodies according to the consensus criteria in a general population aged 75 years or older. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:720–24. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.6.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne JO, Brooks DJ, Rossor MN, Fox NC, Bullock R, Klunk WE, et al. 11 C-PiB PET assessment of change in fibrillar amyloid-beta load in patients with Alzheimer's disease treated with bapineuzumab: a phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled, ascending-dose study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:363–72. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne JO, Laine M, Kaasinen V, Norvasuo-Heilä MK, Någren K, Helenius H. Striatal dopamine transporter and extrapyramidal symptoms in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:1489–93. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.10.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman GC. Vascular dementia: diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN international workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–60. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, Gong SJ, Pike K, Savage G, et al. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:1718–25. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261919.22630.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JC, Bennett DA. Where vascular meets neurodegenerative disease. Stroke. 2010;41(Suppl 1):S144–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.598326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JC, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgens SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:200–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane PD, Zimmerman S, Suchindran C, Reed P, Wang L, Boustani M, et al. The public health impact of Alzheimer's disease, 2000–2050: Potential implication of treatment advances. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002;23:213–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Crane PK, Haneuse S, Li G, Schellenberg GD, et al. Pathological correlates of dementia in a longitudinal, population-based sample of aging. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:406–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnen JA, Postupna N, Larson EB, Crane PK, Rose SE, Montine KS, et al. Pathologic correlates of dementia in individuals with Lewy body disease. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:654–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2009.00371.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens T, Livingston G, Kitchen G, Manela M, Walker Z, Katona C. Islington study of dementia subtypes in the community. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:270–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suotunen T, Hirvonen J, Immonen-Räihä P, Aalto S, Lisinen I, Arponen E, et al. Visual assessment of [(11)C]PIB PET in patients with cognitive impairment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1141–7. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Desmond TJ, Albin RL, Frey KA. Striatal monoaminergic terminals in Lewy body and Alzheimer's dementias. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:767–71. doi: 10.1002/ana.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain. New York: Thieme; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Thal LJ, Kantarci K, Reiman EM, Klunk WE, Weiner MW, Zetterberg H, et al. The role of biomarkers in clinical trials for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:6. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000191420.61260.a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiraboschi P, Salmon DP, Hansen LA, Hofstetter RC, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J. What best differentiates Lewy body from Alzheimer's disease in early-stage dementia? Brain. 2006;129:729–35. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuang D, Simpson K, Larson EB, Peskind E, Kukull W, Bowen JB, et al. Predicting Lewy body pathology in a community-based sample with clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2006;19:195–201. doi: 10.1177/0891988706292755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma AR, Snowden JS, Lloyd JJ, Talbot PR, Mann DM, Neary D. Evaluation of the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria in the differentiation of Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:184–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Pike KE, Cappai R, Masters CL, Rowe CC. The ART of loss: Abeta imaging in the evaluation of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, Small BJ, Petrovich H, Ross GW, Masaki K, Abbott RD, et al. Recent clinical-pathologic research on the causes of dementia in late life: update from the Honolulu-Asia aging study. J Geriatr Psychiatr Neurol. 2005;18:224–7. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]