Abstract

Progression through the cell cycle requires the coord– ination of basal metabolism with the cell cycle and growth machinery. Repression of the sulfur gene network is mediated by the ubiquitin ligase SCFMet30, which targets the transcription factor Met4p for degradation. Met30p is an essential protein in yeast. We have found that a met4Δmet30Δ double mutant is viable, suggesting that the essential function of Met30p is to control Met4p. In support of this hypothesis, a Met4p mutant unable to activate transcription does not cause inviability in a met30Δ strain. Also, overexpression of an unregulated Met4p mutant is lethal in wild-type cells. Under non-permissive conditions, conditional met30Δ strains arrest as large, unbudded cells with 1N DNA content, at or shortly after the pheromone arrest point. met30Δ conditional mutants fail to accumulate CLN1 and CLN2, but not CLN3 mRNAs, even when CLN1 and CLN2 are expressed from strong heterologous promoters. One or more genes under the regulation of Met4p may delay the progression from G1 into S phase through specific regulation of critical G1 phase mRNAs.

Keywords: G1 cyclin/G1–S transition/methionine/SCF ubiquitin ligase

Introduction

Availability of nutrients in the environment is essential for cell growth and cell cycle progression. In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nutrient deprivation can elicit different responses such as cell cycle arrest in G1 phase, sporulation or pseudohyphal growth. In particular, sufficient sources of carbon, phosphate, nitrogen and sulfur are required for yeast cells to pass through the cell cycle commitment point called Start in late G1 phase (reviewed in Pardee, 1989; Hartwell, 1994; Sherr, 1994; Polymenis and Schmidt, 1999).

Budding yeast can satisfy their elemental sulfur requirement through the uptake and subsequent metabolism of a large number of either inorganic or organic sulfur compounds (reviewed in Thomas and Surdin-Kerjan, 1997). In addition to the biosynthesis of the two sulfur amino acids methionine and cysteine, reduced sulfur atoms are needed to synthesize S–adenosylmethionine (AdoMet), a molecule central to general metabolism. AdoMet is indeed next to ATP for the number of reactions in which a biological compound is used: AdoMet is the main donor of methyl groups for methylation of nucleic acids, proteins and lipids, serves as a precursor for the biosynthesis of the polyamines and is also the substrate for numerous reactions in vitamin biosynthesis and nucleotide modification.

Sulfur flux through the sulfate assimilation pathway and the metabolic arms specific for the methionine and cysteine syntheses is controlled by the intracellular content of AdoMet. A key component of this regulation is the MET gene transcriptional activator Met4p and its associated cofactors Cbf1p, Met28p, Met31p and Met32p (reviewed in Thomas and Surdin-Kerjan, 1997). Repression of Met4p-dependent transcription in response to increased intracellular AdoMet is mediated by the SCFMet30 complex, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (Patton et al., 1998; Rouillon et al., 2000). Met4p degradation and transcriptional activity are governed by an autoregulatory loop. When intracellular AdoMet is low, Met4p-containing transcription activation complexes drive expression of the MET gene network, including the MET30 gene. Once expressed, Met30p targets Met4p for degradation via SCFMet30 and thereby limits expression of the MET genes in response to high intracellular AdoMet (Rouillon et al., 2000).

SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes target specific substrates for degradation, as determined by their F–box component (reviewed in Craig and Tyers, 1999). In addition to Met4p, SCFMet30 appears to target Swe1p, a Cdc28p inhibitory kinase necessary for the morphological checkpoint (Kaiser et al., 1998). SCFMet30 is one of three SCF complexes identified in yeast. SCFCdc4 targets the cell cycle and transcriptional regulators Sic1p, Far1p, Gcn4p, Ctf13p and Cdc6p for degradation, while SCFGrr1 is responsible for the degradation of the G1 cyclins, Cln1p and Cln2p, of the Cdc42p effector Gic1p, and regulation of the glucose repression pathway. Proteins similar to Met30p exist in other fungi, Drosophila and mammals, and are the SconB, Slimb and β–TrCP proteins, respectively (Kaiser et al., 1998; Margottin et al., 1998). Recently, the β–TrCP/Slimb proteins have been implicated in the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of protein targets in NF–κB, Wnt/Wingless and Hedgehog pathways (reviewed in Maniatis, 1999). Also, β–TrCP was shown to trigger the degradation of the lymphocyte receptor CD4 via the HIV protein Vpu (Margottin et al., 1998).

Regulation of the cell division cycle requires the activation of the essential cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) Cdc28p by the G1 cyclins Cln1p, 2p and 3p (reviewed in Nasmyth, 1996). Cyclin-CDK activity is rate-limiting for passage through Start, and control of cyclin-CDK activity has been reported at multiple levels including inhibition by cyclin inhibitors, transcription, translation and degradation (Hartwell, 1994; Sherr, 1994; Nasmyth, 1996; Polymenis and Schmidt, 1999). For example, non-degradable forms of the G1 cyclins, such as Cln3–1, cause hyperactivation of Start and hence a decreased critical cell size (Nash et al., 1988). Repression of CLN3 mRNA translation is required for cell cycle arrest in starvation and high iron conditions (Polymenis and Schmidt, 1997; Philpott et al., 1998).

While the MET network is only essential in the absence of sulfur amino acids, MET30 is an essential gene under all nutrient conditions (Thomas et al., 1995). Here, we show that the essential function of Met30p is the regulation of Met4p transcriptional activity. Surprisingly, Met4p regulation is critical for progression through Start. Our results argue that the misregulation of genes under the control of Met4p inhibits passage through Start by preventing the accumulation of important G1 phase transcripts, including those of the genes encoding the G1 cyclins, Cln1p and Cln2p.

Results

Inactivation of MET4 suppresses met30Δ lethality

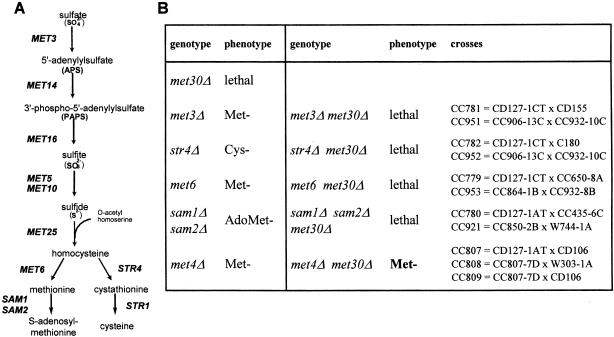

MET30 is an essential gene and encodes a negative regulator of the sulfur amino acid biosynthesis pathway (Thomas et al., 1995). The unregulated synthesis of a particular sulfur-containing metabolite might therefore be responsible for the lethality of a met30Δ strain. To test this hypothesis, we crossed a met30::LEU2 strain harboring a LexA-MET30, HIS3 plasmid with a battery of mutants that each specifically block one metabolic arm of the sulfur network (met3Δ, met6Δ, str4Δ and sam1Δsam2Δ; Figure 1A; see Materials and methods). We also included a cross with a met4Δ mutant strain in our analysis as Met30p was shown to trigger Met4p degradation in response to an increase in intracellular AdoMet (Rouillon et al., 2000). Single deletions of MET3, MET6 or STR4 genes as well as the double deletion of the SAM1 and SAM2 genes did not alter the met30Δ lethality phenotype, indicating that the met30Δ lethality was not due to the accumulation of a sulfur-containing metabolite. In contrast, deletion of MET4 bypassed the lethality of the met30Δ strain (Figure 1B), suggesting that the essential function of Met30p might be the regulation of Met4p.

Fig. 1. (A) Simplified view of sulfur amino acid biosynthesis in yeast. (B) The met4Δ disruption mutation specifically suppresses the lethality induced by the loss-of-function mutation met30Δ. See Materials and methods for details of the crosses.

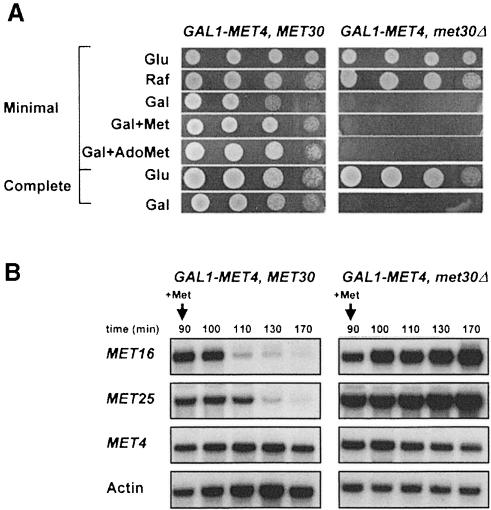

We made a conditionally viable met30Δ mutant by constructing strains that could express MET4 under the GAL1 promoter in the absence of MET30. As shown in Figure 2A, expression of GAL1–MET4 in met30Δ cells induces lethality in minimal or complete galactose-containing medium. Also, repressive amounts of extracellular methionine or AdoMet, which have been shown to trigger the degradation of Met4p, did not prevent the detrimental effect of MET4 expression in met30Δ mutants. Similar results were obtained with cells grown in sulfur-less B medium in the presence of homocysteine or methionine used as the sulfur source (data not shown). Altering the levels of GAL1–MET4 expression by spotting the mutants on galactose concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2.5% was equally effective in inducing lethality (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Expression of Met4p from the GAL1 promoter is lethal in met30Δ cells. (A) Serial dilutions of the CC932-6D (met4::GAL1–MET4 MET30) and CC932-8B (met4::GAL1–MET4 met30::LEU2) strains were plated on media containing 2% glucose (Glu), raffinose (Raf) or galactose (Gal) as carbon source in the absence or presence of 1 mM l-methionine (Met) or 0.2 mM AdoMet. (B) CC932-6D (met4::GAL1–MET4 MET30) and CC932-8B (met4::GAL1–MET4 met30::LEU2) cells were grown in raffinose medium and expression was induced by transferring the cells to a fresh galactose (2%) medium for 90 min. A repressing amount of l-Met (1 mM) was then added and total RNA was extracted at the times indicated. Expression of MET16, MET25 and GAL1–MET4 were determined by Northern analysis. The actin probe was used as a control of the amount of RNA loaded.

The first functional analyses of Met30p were carried out in MET30-1 and MET30-2 strains, point mutants of MET30 that are unable to fully repress MET gene expression in response to high levels of extracellular methionine (Thomas et al., 1995). The viable conditional met30Δ mutant provided us with the opportunity to verify that Met30p function is absolutely required for Met4p regulation. We analyzed the AdoMet-mediated repression of two structural genes from the sulfate assimilation pathway (MET16 and MET25) in cells expressing MET4 from the GAL1 promoter in the presence or absence of MET30. The two corresponding strains (met4::GAL1–MET4 and met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ) were first grown in the presence of raffinose for eight generations, transferred to a medium containing galactose to induce GAL1–MET4 gene expression for 90 min before a repressive concentration of methionine was added, and samples extracted at regular time intervals after methionine addition. As shown in Figure 2B, Northern blot analysis demonstrated that repression of MET16 and MET25 transcription in response to high methionine was dependent on MET30. MET16 and MET25 genes were repressed with wild-type kinetics in met4::GAL1–MET4 strains, but were insensitive to high extracellular methionine in met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells. Insensitivity of the MET16 and MET25 genes to high extracellular methionine in met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells is consistent with the above results showing that repressive amounts of extracellular methionine or AdoMet did not suppress the lethality induced by MET4 expression in met30Δ cells. As a control, the transcription of the GAL1–MET4 fusion gene was not affected by the presence of methionine. These results confirmed our previous findings that Met30p is required for repression of the MET gene network.

To function as a transcriptional activator, Met4p is recruited to the sequence-specific upstream regions of MET genes as a part of multiprotein complexes. Depending on the gene, different combinations of the Cbf1p, Met28p, Met31p and Met32p factors are assembled and tether Met4p to DNA (Kuras et al., 1997; Blaiseau and Thomas, 1998). To determine whether, in addition to Met4p, components of these complexes were required for the essential function of Met30p, we crossed a met30::LEU2 strain harboring a LexA-MET30, HIS3 plasmid with the single cbf1Δ or met28Δ mutants as well as with a met31Δmet32Δ double mutant. The results of these genetic tests showed that met32Δ met30Δ spores could be recovered while deletion of CBF1, MET28 or MET31 had no effect on the lethality of the met30Δ mutation (Table I). The essential function of Met30p might therefore be required to antagonize a specific Met4p–Met32p transcription complex.

Table I. Suppression of met30Δ-induced lethality by inactivation of the MET32 gene.

| Genotype | Phenotype | Genotype | Phenotype | Crosses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| met30Δ | lethal | |||

| met4Δ | Met– | met4Δ met30Δ | Met– | see Figure 1 |

| met28Δ | Met– | met28Δ met30Δ | lethal | CC958 = CD130-1A × CC850-2B |

| cbf1Δ | Met– | cbf1Δ met30Δ | lethal | CC806 = CD127-1AT × R31-5C |

| met31Δ | Met+ | met31Δ met30Δ | lethal | CC867 = C847-1D × CD179 |

| met32Δ | Met+ | met32Δ met30Δ | Met+ | CC867 = C847-1D × CD179 |

Met4p regulation is essential for cell viability

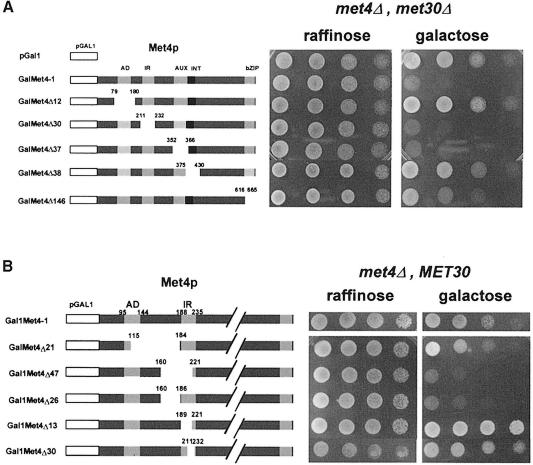

We have recently reported the SCFMet30-dependent degradation of Met4p in response to high extracellular methionine (Rouillon et al., 2000). Our genetic data, demonstrating that the essential function of Met30p could be bypassed by the deletion of MET4 or MET32, suggested that the lethality of a met30Δ strain might be due to unregulated activity of Met4p, as Met32p lacks transcriptional activation function (Blaiseau et al., 1997). Detailed analysis of the functional organization of Met4p has identified one activation domain (AD), two regulatory regions required for the AdoMet response, called the inhibitory region (IR) and the auxiliary domain (AUX), and two domains required for tethering Met4p to DNA via protein–protein interactions with Met31p/Met32p and Met28p/Cbf1p, called the INT domain and the bZIP domain, respectively (Kuras and Thomas, 1995; Blaiseau and Thomas, 1998). To determine which particular aspect of Met4p function is required to induce lethality in the absence of Met30p, different mutant derivatives of Met4p were expressed from the GAL1 promoter in met4Δ met30Δ cells and tested for viability. As shown in Figure 3A, deletion of the AD (pGalMet4Δ12) or INT (pGalMet4Δ38) domains of Met4p rescued the GAL1–MET4-induced lethality in met4Δ met30Δ cells. In contrast, deletion of the two AdoMet regulatory regions, the IR (pGalMet4Δ30) and AUX (pGalMet4Δ37) domains, did not prevent lethality. This is consistent with our findings that met4Δ and met32Δ, but not cbf1Δ or met28Δ, can bypass the met30Δ arrest, and reinforces the idea that an unregulated transcriptional activity of a DNA-bound complex containing Met4p and Met32p is lethal. This notion might be too simplified, however, because removal of the Met4p bZIP domain thought to bind Met28p and Cbf1p results in a partial rescue of met30Δ (pGalMet4Δ146; Figure 3A), while the simple deletion of MET28 or CBF1 is not sufficient to bypass the met30Δ lethality.

Fig. 3. (A) Expression of Met4p derivatives in met4Δ met30Δ cells. Schematic representations of the modified Met4p derivatives expressed from the GAL1 promoter region are shown. Plasmids encoding the fusion genes were introduced into CC807-1C (met4::TRP1 met30::LEU2) cells. Serial dilutions of the resulting transformants were plated on media containing 2% raffinose or galactose as carbon source. (B) Expression of Met4p derivatives in met4Δ MET30 cells. Details of the deletions are scaled up. Plasmids encoding the fusion genes were introduced into CD106 (met4::TRP1) cells. Serial dilutions of the resulting transformants were plated on media containing 2% raffinose or galactose as carbon source.

Given the expectation that Met30p-mediated regulation of Met4p requires an interaction between the two factors, it could be predicted that mutations within Met4p should exist that by impairing the Met30p–Met4p interaction would cause lethality even in cells expressing MET30. We had previously mapped the IR domain as a region of Met4–Met30 protein interaction by two-hybrid analysis (Thomas et al., 1995); however, our IR deletion mutant was unable to induce lethality in the presence of Met30p. This suggested that the Met4 IR domain may include amino acid residues outside of 189–235, consistent with data reported by Omura and colleagues, who isolated a Met4p point mutant (F156S) that was unresponsive to high extracellular methionine (Omura et al., 1996). We thus constructed a new set of deletions around the IR region of GAL1–MET4 and expressed them in met4Δ MET30 cells. Two derivatives, Met4Δ47 (amino acids 160–221) and Met4Δ26 (amino acids 160–186), induced lethality in met4Δ MET30 cells (Figures 3B and 4E), indicating that the Met30p-mediated regulation of Met4p was dependent on a larger IR domain than previously reported, and supporting the notion that unregulated Met4p activity might be responsible for the lethality of met30Δ mutants.

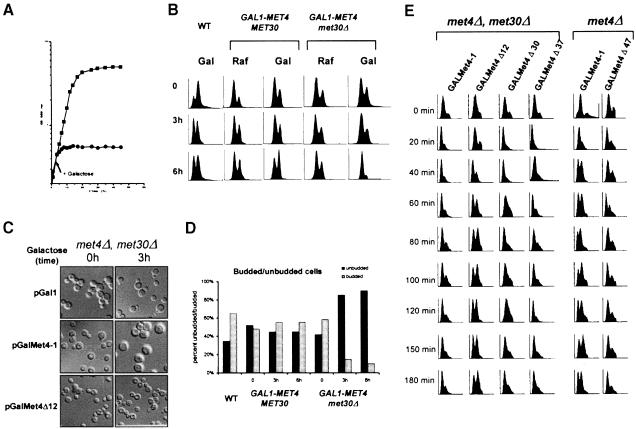

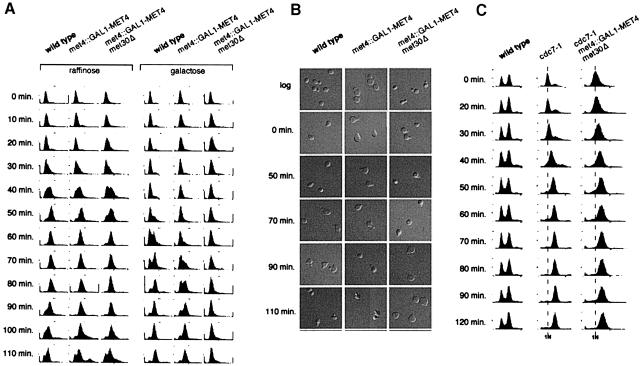

Fig. 4. Conditional met30Δ mutant cells arrest as large unbudded cells with 1N DNA. (A) CC932-6D (met4::GAL1–MET4 MET30) (▪) and CC932-8B (met4::GAL1–MET4 met30::LEU2) (•) cells were grown in the presence of 2% raffinose as carbon source. At the time indicated by the arrow, 2% galactose was added to each culture and growth was followed by measuring the OD650 for the times indicated. (B) Wild type, met4::GAL1–MET4 MET30 and met4::GAL1–MET4 met30::LEU2 were grown in the presence of raffinose, cultures were divided into two, filtered and transferred to raffinose or galactose medium. FACS analyses were then performed at the times indicated. (C) CC807-1C (met4::TRP1 met30::LEU2) cells were transformed by the pGal316, pGalMet4-1 or pGalMet4Δ12 plasmids. Resulting transformants were grown in the presence of 2% raffinose as carbon source. Cultures were then filtered and transferred to a galactose (2%) medium. Photographs of the cells were then taken at the times indicated. (D) Budding index of the cells grown in (A). (E) CC807-1C (met4::TRP1 met30::LEU2) or CD106 (met4::TRP1) were transformed by the plasmids indicated. Resulting transformants were grown in raffinose medium to early log phase and arrested by α factor for 3 h in 2% galactose. The cells were released from α factor by washing with fresh galactose medium and analyzed for their DNA content by flow cytometry at the times indicated.

The essential function of Met30p is required for passage through G1 phase

Conditional expression of the MET4 gene from a GAL1 promoter in met4Δ met30Δ double mutants allowed us to characterize the phenotype of met30Δ mutants. We performed growth curve analysis to determine the number of generations before arrest, fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis to measure DNA content, and determined the budding index. Early log phase cultures of met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ were grown in raffinose, split into two, galactose added to one culture, and cell number measured over time. Within one doubling the GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells had arrested, while the raffinose culture continued to increase in cell number (Figure 4A). To examine whether the cells had any particular cell cycle arrest phenotype, we grew parallel cultures of met4::GAL1–MET4 and met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ strains in raffinose and galactose, and took samples at 0, 3 and 6 h. As shown in Figure 4B, expression of MET4 in the absence of MET30 causes the cells to accumulate in G1 with unreplicated DNA. Microscopic observation showed that >90% of the GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells remain unbudded 6 h after the shift to the galactose medium (Figure 4C and D).

The G1 arrest phenotype of met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells correlated with the requirement for the Met4p activation domain to induce lethality in these strains. Expression of GAL1–MET4ΔAD produced little alteration of the FACS profile, while expression of GAL1–MET4 in met4Δ met30Δ cells caused a G1 arrest (Figure 4E). Also, expression of GAL1–MET4ΔIR(160–221), which had been shown to induce lethality in the presence of MET30, also arrested the cells in G1 phase. Expression of other GAL1–MET4 derivatives, described above, showed FACS profiles similar to wild type. Thus, unregulated activity of Met4p, either by lack of the IR(160–221) domain or by deletion of MET30, is sufficient to cause a G1 arrest.

There are multiple biological pathways that can cause an unbudded G1 phenotype when disrupted (Nasmyth, 1996). To gain insight into the mechanism responsible for the G1 arrest observed in the GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells, we undertook a detailed study of the characteristics of the GAL1–MET4 met30Δ arrest. To map the arrest position of the met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ mutant, we arrested an asynchronous culture growing in raffinose with mating pheromone for 2 h, split the culture into two, added raffinose to one half and galactose to the other half for 20 min, released the culture into pheromone-free medium, and took samples at 10 min intervals to measure DNA content and budding morphology. Cells in raffinose proceeded through the cell cycle with a similar FACS profile to wild type (Figure 5A), demonstrating that in the absence of Met4p, the deletion of MET30 has only a marginal effect on cell cycle progression. In contrast, the met4:: GAL1–MET4 met30Δ mutants remained in G1 phase without undergoing DNA replication (Figure 5A) or initiating budding (Figure 5B). When GAL1–MET4 was induced in the met4Δ met30Δ mutants after the release from pheromone, the cells progressed through the cell cycle before accumulating in G1 phase (data not shown), suggesting that the effects of GAL1–MET4 are specific to the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Unregulated Met4p might, therefore, function at or shortly after the pheromone arrest point to inhibit passage through Start. Consistent with this hypothesis, overexpression of MET4, still under the control of endogenous levels of Met30p, induces a 20 min delay through Start (Figure 5A). Met30p was originally identified as a mutant that was defective for repression of MET gene transcription (Thomas et al., 1995). Given that overexpression of MET4 could delay passage through G1 of the cell cycle by 20 min, we examined the progression of MET30-1 mutant cells through the cell cycle by FACS analysis. MET30-1 cells were delayed for passage into S phase by 10 min (data not shown), indicating that non-lethal mutations in MET30 that are partially defective for Met4p regulation are also capable of producing a G1–S phase delay.

Fig. 5. The essential function of MET30 is required at or after the pheromone arrest position, but prior to the initiation of budding or DNA replication. (A) Wild-type, met4::GAL1–MET4 and met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells were grown in rich raffinose medium to early log phase and arrested with α factor for 2 h. The cells were then split into two cultures and raffinose added to one, while galactose was added to another for 20 min. The cells were released from α factor by washing with fresh medium and time points taken at the designated intervals. (B) Photographs of the cells in (A) demonstrate that the met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ arrest as large unbudded cells. The tear shape of the cells is due to effects of the pheromone. (C) MET30 is required before the cdc7-1 arrest point. Wild-type, cdc7-1 and cdc7-1 met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cultures were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, had galactose added for 30 min, and were then shifted to 25°C and samples taken at the time indicated.

The shift from a pheromone-induced arrest to a met30Δ arrest demonstrated that the met30Δ arrest phenotype was at or after the pheromone arrest point but prior to the DNA replication and budding initiation point. In the converse experiment, i.e. arresting the met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells in G1 phase in galactose and releasing them into glucose and pheromone medium, the cells were unable to recover from the prolonged GAL1–MET4 arrest. As an alternative, we constructed a met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cdc7-1 mutant, arrested the cells at 37°C and released them into a galactose-containing medium at 25°C. The Cdc7p kinase is required for the initiation of DNA replication, but not for budding (Yoon et al., 1993). cdc7-1 mutants arrested at 37°C with small buds and 1N DNA content (Figure 5C), and progressed through S and G2 phase upon shift to 25°C. Similarly, met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cdc7-1 mutants arrested in G1 phase at 37°C, and progressed through S and G2 phase when shifted to 25°C in galactose, placing the met30Δ arrest position after the pheromone block but before the Cdc7p requirement point in the cell cycle.

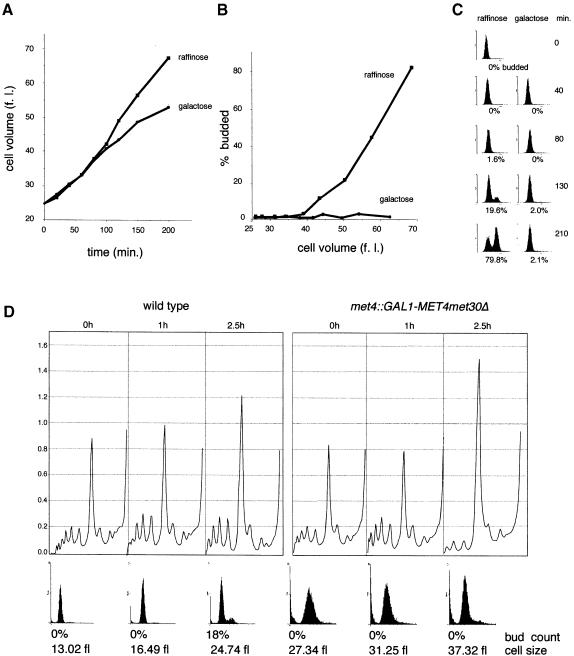

G1-phase-arrested met30Δ mutants are compromised for efficient growth and translation

Start mutants can be categorized into those affecting growth such as mutations in the cAMP pathway or the translational machinery, and those affecting division such as mutations in CDC28 or the G1 cyclins (reviewed in Hartwell, 1994). To determine which component of Start was altered in the conditional met30Δ mutants, we monitored the rate of growth in small, unbudded met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ G1 cells collected by centrifugal elutriation and then grown in raffinose or galactose (Figure 6A). As expected, in raffinose medium cells grew steadily over time and passed through Start (25% budded) at a cell volume of 50 fl. These cells progressed through S phase and into G2–M phase, as indicated by the increase in bud index and DNA content (Figure 6B and C). In contrast, cells grown in galactose medium did not initiate budding (Figure 6B) and maintained a 1N DNA content (Figure 6C), but did, however, accumulate mass over time (Figure 6A). Initially, the conditional met30Δ mutants grown in galactose medium accumulated mass at a rate equal to those in raffinose medium, but after 100 min the rate of growth was slowed somewhat.

Fig. 6. Conditional G1-arrested met30Δ mutants are slowed for cell growth and translation. Cultures of small G1 met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells grown in raffinose were collected by centrifugal elutriation, divided into two, and raffinose added to one culture and galactose to the other. Samples were taken at the times indicated to measure (A) cell volume, (B) budding index and (C) DNA content by flow cytometry. (D) Polysome profiles of wild-type or met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells through the Start position. G1 cells were collected by centrifugal elutriation in a rich, raffinose medium, galactose was added at time 0, and samples were taken at the times indicated for polysome profiles, flow cytometry and budding analysis.

To determine whether the decreased rate of mass accumulation in the met30Δ mutants might be due to defects in translation, we measured the incorporation of [35S]methionine/cysteine into total protein, and examined the polysome profiles of the conditional met30Δ mutants. [35S]methionine/cysteine incorporation was decreased by 20% in the conditional met30Δ mutants after 2.5 h in galactose. Similarly, the number of discrete polysome peaks and UV absorbance of the polysome peaks were slightly reduced in the met30Δ mutants after 2.5 h (data not shown). To perform a more detailed analysis, we used synchronized G1 cells isolated by centrifugal elutriation and examined polysome profiles of wild-type and met30Δ cells as a function of time. In comparison with wild-type cells, the extent of polyribosome formation was reduced and, correspondingly, the 80S ribosome peak was increased in the met30Δ mutants at 2.5 h, by which time wild-type cells had passed through Start (Figure 6D). It therefore appears that met30Δ cells are able to reach the critical cell size required for passage through Start but gradually become impaired in translation.

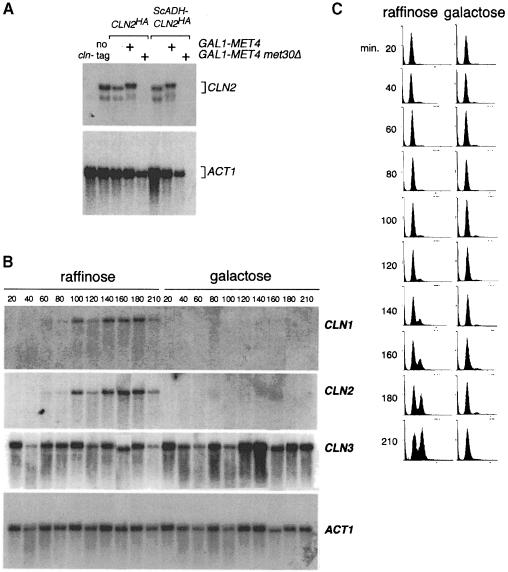

Various G1 cyclin RNA transcripts are reduced in met30Δ mutants

As the conditional met30Δ strain was only slightly compromised for translation, we reasoned that other components of the cell division machinery might be altered in these cells. We therefore tested whether overexpression of the G1 cyclins could rescue the met30Δ phenotype. Expression of the genes encoding the G1 cyclins, CLN1, CLN2, CLN3, CLN3-1, PCL1 or PCL2, and the S and G2 cyclins, CLB2 or CLB5, from the GAL1 promoter in met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ mutants was unable to bypass the lethal phenotype (data not shown). Intriguingly, even if CLN1 and CLN2 genes were expressed from the GAL1 promoter for 3 h, Cln1 or Cln2-Cdc28 kinase activity could not be detected in the met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ mutant strain. Similarly, Western analysis revealed that Cln1p and Cln2p were barely detectable (data not shown). To ensure that the decrease in protein level was not due to repression of the GAL1 promoter, we also examined the levels of Cln2p expressed from the endogenous promoter or from the constitutive ADH1 promoter. In each case, Cln2p was undetectable in the met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells (data not shown). We next performed Northern analysis with total RNA extracted from met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells grown in the presence of galactose and found that CLN2 transcripts were undetectable, while in contrast, ACT1 mRNA levels were clearly detectable, although slightly reduced (Figure 7A). As the protein level had suggested, CLN1 transcripts were also undetectable, as were PCL2 transcripts, while CLN3, WHI3 and WHI4 transcripts appeared normal (data not shown).

Fig. 7. Conditional met30Δ mutants lack CLN1 and CLN2 mRNA transcripts. (A) Northern analysis of CLN mRNA transcripts demonstrates a lack of CLN2 mRNA expressed from the endogenous or the ADH1 promoter in galactose-grown met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells. (B) CLN1 and CLN2, but not CLN3 mRNAs, fail to accumulate in elutriated G1 met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells grown in galactose, but accumulate normally in met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells grown in raffinose. Cells were grown in a rich, raffinose medium, the culture split into two, and raffinose added to one culture and galactose to the other. Samples were taken for (B) Northern analysis and (C) flow cytometry.

It was important to determine whether CLN1 and CLN2 mRNAs failed to accumulate during G1 phase in the met30Δ mutant cells, or whether the lack of detectable transcripts was a secondary consequence of the prolonged G1 arrest. We therefore collected small, unbudded, G1 met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ cells by centrifugal elutriation, added raffinose to one half of the culture and galactose to the other, and collected samples for Northern, FACS and budding analysis. The cells grown in raffinose medium expressed CLN1, CLN2 and CLN3 transcripts appropriately, grew in cell size, initiated budding and replicated their DNA (Figure 7B and C). In contrast, the cells grown in galactose medium failed to accumulate CLN1 and CLN2 mRNAs but did have wild-type levels of CLN3 mRNAs (Figure 7B). As before, the cells did not initiate budding or DNA replication (Figure 7C). The inability of met30Δ cells to accumulate CLN1/2 and PCL1/2 mRNAs is sufficient to account for the arrest at Start (Espinoza et al., 1994; Measday et al., 1994). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other G1 phase transcripts are also affected.

Discussion

Met4p and passage through the G1 phase of the cell cycle

In this study, we demonstrate that components of the MET gene network are critical for passage through Start in budding yeast. Our genetic analysis shows that the essential function of MET30 is bypassed by deletion of MET4, the gene that encodes the main transcriptional activator of the sulfur amino acid biosynthesis pathway, and that unregulated Met4p activity is lethal. The creation of a met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ conditional mutant has allowed us to confirm the function of Met30p in regulating Met4p function (Figure 2B) and to characterize the arrest phenotype of met30Δ cells (Figures 3 and 4). Surprisingly, met30Δ conditional mutants arrest as large, unbudded cells with unreplicated DNA. Genetic analysis has allowed us to determine that the G1 arrest phenotype of the met30Δ conditional mutant is most likely not a result of an unbalanced synthesis of a sulfur metabolite because mutations in structural genes of the MET pathway do not alter the lethal phenotype of met30Δ strains (Figure 1). The G1 arrest phenotype is dependent on the transcriptional activity of Met4p, because Met4p mutants without a transcriptional activation domain (Met4ΔAD), or that are incapable of binding the cofactors Met31p and Met32p (Met4ΔINT), are not lethal in a met30Δ background (Figure 3A). Consistent with these results, the met32Δ mutation is also capable of bypassing the met30Δ lethal phenotype (Figure 1B). The fact that the met32Δ mutation, but not the met31Δ mutation, was specifically capable of bypassing the met30Δ mutation was somewhat unexpected since Met31p and Met32p, which are two highly homolo– gous zinc finger factors, are thought to have redundant functions (Blaiseau et al., 1997). For instance, only the double met31Δ met32Δ mutant is a methionine auxotroph, while single met31Δ and met32Δ mutants are not (Blaiseau et al., 1997). Likewise, mobility shift assays revealed no difference between the Met4–Met28–Met31 and Met4–Met28–Met32 complexes assembled on the MET3 and MET28 promoter regions (Blaiseau and Thomas, 1998). Our results suggest, however, that either the precise function of Met31p and Met32p, or at least the amount of the two proteins required for the assembly of the Met4p-containing complexes, might differ.

Regulation of Met4p by Met30p is dependent on a Met30p binding region called the IR (Thomas et al., 1995). Accordingly, a Met4p derivative lacking the IR region (amino acids 189–235) was recently shown to be less sensitive to SCFMet30-triggered degradation in response to high extracellular methionine (Rouillon et al., 2000). However, during our analysis of the regions of Met4p required for the G1 arrest in met30Δ mutants, we found that the Met30p–Met4p interaction region previously defined by two-hybrid analysis did not entirely correlate with the Met4p region required for inhibition by Met30p because deletion of the former was not sufficient to induce a G1 arrest in cells carrying MET30. Deletion of a slightly greater domain (amino acids 160–220, Met4Δ47) was, in contrast, capable of inducing a G1 arrest in a MET30 background. We suggest that our previously defined IR domain is required for the Met30p–Met4p two-hybrid interaction, yet full Met30p repression of Met4p requires amino acids 160–220 of Met4p.

Conditional met4::GAL1–MET4 met30Δ mutants arrest in G1 phase within the first cell cycle after a shift to a galactose medium (Figures 4A and 5). The essential function of Met30p is required at or after the pheromone arrest point, but before budding or DNA replication has been initiated. Overexpression of MET4 alone does not cause a G1 arrest, but it is sufficient to cause a slight delay from G1 into S phase, suggesting that overexpression of Met4p can transiently overcome a limiting amount of repression by SCFMet30. Indeed, the MET30-1 mutation, which is partially defective in Met4p repression in response to high extracellular methionine (Thomas et al., 1995), also exhibits a delay in passage through G1 phase. That the MET30-1 mutation is not lethal may indicate that while some excess Met4p activity is admissible in the cell, a complete lack of regulation, such as in met30Δ, is intolerable.

Models for Met4p function in the G1 phase

We are currently exploring two models for the manifestation of the met30Δ G1 arrest phenotype. In the first one, a specific transcription activation complex comprising Met4p and Met32p regulates the expression of a gene or series of genes that inhibits passage though G1 phase. Since the G1 arrest is dependent upon the Met4p activation domain, transcriptional activity in this model would arise specifically from Met4p while Met32p would act by recruiting Met4p to DNA, as Met32p does not appear to have transcriptional activity (Blaiseau et al., 1997). Transcription of this G1 phase ‘inhibitor’ gene might not depend on the known Met4p transcription complexes that are assembled upstream of the classical MET genes because deletion of CBF1 and MET28 does not suppress the lethality of the met30Δ mutation (Figure 1B). Likewise, the ‘inhibitor’ gene(s) might not be required for methionine biosynthesis because the met32Δ met30Δ cells are methi– onine prototrophs. Thus, Met4p might be responsible for the regulation of multiple gene networks and assemble into numerous transcriptional activation complexes. An alternative model for the met30Δ G1 arrest might be that, due to a lack of Met4p degradation, increased protein levels of Met4p inhibit passage through G1 phase by associating specifically or non-specifically with other transcriptional complexes. However, the specificity of the met32Δ mutation to bypass the G1 arrest, as well as the altered CLN1 and CLN2 but not CLN3 transcript levels, argue for more than Met4p non-specifically sequestering the general transcription machinery away from promoters of G1-specific genes.

Potential mechanisms for the conditional met30Δ G1 arrest

A variety of G1 mutants that arrest as unbudded cells with unreplicated DNA have been identified in S.cerevisiae, including cell division mutants (such as cdc28 and cln mutants) and cell growth and translation mutants (such as the Ras-cAMP and tor– mutants; Hartwell, 1994; Nasmyth, 1996; Polymenis and Schmidt, 1999). Because our GAL1–MET4 met30Δ mutants were unable to pass through Start, we examined both possibilities as the potential route to the G1 arrest phenotype. We used synchronized cells to determine whether the met30Δ mutants were capable of growth in G1 phase, and to determine whether translation was compromised (Figure 6). While the met30Δ mutant did continue to accumulate mass in G1 phase after a prolonged growth arrest, translation was slightly slowed in comparison with MET30 cells, and polysome profiles showed a corresponding defect in translational apparatus. The delayed kinetics of the protein synthesis response compared with the first cycle G1 arrest suggest that the effect on translation is a secondary consequence of the arrest. In contrast, we unexpectedly found that CLN1, CLN2 and PCL2 transcripts were entirely absent from the met30Δ cells, while CLN3, WHI3 and WHI4 transcripts were unaffected. Since the loss of G1 cyclin transcripts occurs well before any effects on protein synthesis, we suggest that the effect on G1 transcripts might directly result from unregulated Met4p activity. Because cln1 cln2 pcl1 pcl2 mutants arrest at Start, the absence of these transcripts may account for the phenotype of met30Δ cells. As CLN transcripts are very unstable even in wild-type cells, unregulated Met4p activity in the met30Δ mutant may hyperactivate a G1 cyclin RNA degradation mechanism. Our results further indicate that any such pathway would presumably not affect CLN3 mRNA. In possible comparison, an SCF-like complex called VCB–CUL2 (comprised of VHL–ElonginB/C–CUL2) is thought to regulate, either directly or indirectly, accumulation of hypoxia-inducible mRNAs by targeting a protein for degradation in hypoxic conditions (reviewed in Kaelin and Maher, 1998; Tyers and Rottapel, 1999). Nutrient-dependent modifications of RNA stability have also been identified as a mechanism of glucose repression (Lombardo et al., 1992; Cereghino and Scheffler, 1996). While control over transcription, translation and protein stability has been explored as a means to control G1 cyclin levels, to our knowledge, our results constitute the first suggestion of a control at the level of G1 cyclin mRNA stability.

Methionine and the cell cycle

Connections between the cell cycle and methionine were first identified by Unger and Hartwell (1976) with the study of met mutants that arrested in G1 phase in the absence of methionine, and of methionine tRNA synthase mutants that arrested in G1 phase even in the presence of methionine. They predicted that a ‘signal’ allowed the cell to arrest specifically in G1 phase and acted at the level of protein biosynthesis. Whether the met30Δ G1 arrest is similar to the arrest described by Unger and Hartwell (1976) has yet to be determined. DNA microarray analysis has also revealed that the expression of most of the MET genes is specifically activated during S phase (Spellman et al., 1998), suggesting that cell cycle and sulfur amino acid metabolism are closely linked. Our study reinforces this connection by linking the regulation of the main regulator of the MET network, Met4p, with the cell cycle. Important questions that arise from this work are whether and how regulation of Met4p might couple methionine with passage through G1 phase. Cell size experiments and the rate of passage through Start in synchronized, small G1 cells suggest that in the presence of high extracellular methionine, cells reset their critical cell size to a larger volume and delayed passage through Start (E.E.Patton and M.Tyers, unpublished data). This initial finding is superficially at odds with the clear inhibition of Start by excessive Met4p activity. However, as the met30Δ met32Δ mutant is a methionine prototroph, it is possible that a specific Met4–Met32 transcription complex responds to a different signal than an increase of intracellular AdoMet.

Finally, the sulfur amino acid biosynthesis pathway is highly conserved in eukaryotes (Griffith, 1987). Connections between methionine metabolism and cell cycle control have already been noted in mammals. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated the methionine dependence of numerous transformed cells and tumors (Hoffman, 1997). More recently, it was shown that athymic mice that are grafted with human cancers and fed a methionine-free diet are greatly reduced in their tumor burden (Kokkinakis et al., 1997). The results reported here emphasize the importance of future studies on the coordination of nutrients, such as methionine, with the cell cycle.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and media

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this work are listed in Table II. They are all isogenic to the W303 background. Standard yeast media were prepared as described by Chérest and Surdin-Kerjan (1992). Saccharomyces cerevisiae was transformed after acetate chloride treatment as described by Gietz et al. (1992). Genetic crosses, sporulation, dissection and scoring of nutritional markers were as described by Sherman et al. (1979).

Table II. Yeast strains.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| C180 | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, str4::URA3 | Chérest and Surdin-Kerjan (1992) |

| CD127-1AT | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met30::LEU2, pLexMet30-4 | Thomas et al. (1995) |

| CD127-1CT | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met30::URA3, pLexMet30-4 | Thomas et al. (1995) |

| CD106 | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::TRP1 | Thomas et al. (1992) |

| CD130-1A | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met28::LEU2 | Kuras et al. (1996) |

| CD155 | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met3::URA3 | this study |

| CD171 | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::URA3, met30::LEU2 | this study |

| CD179 | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met31::LEU2, met32::TRP1 | Blaiseau et al. (1997) |

| CC435-6C | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, sam1::URA3, sam2::URA3 | Thomas et al. (1988) |

| CC807-1C | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::TRP1, met30::LEU2 | this study |

| CC807-7D | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::TRP1, met30::LEU2 | this study |

| CC847-1C | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met30::URA3, pLexMet30-4 | this study |

| CC849-8A | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::TRP1 | this study |

| CC850-2B | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::TRP1, met30::URA3 | this study |

| CC864-1B | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met6 | this study |

| CC867-1B | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met30::URA3, met31::LEU2, met32::TRP1 | this study |

| CC867-1D | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met30::URA3, met32::TRP1 | this study |

| CC874-18D | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, str4::URA3 | this study |

| CC906-13C | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met3::URA3 | this study |

| CC932-6D | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::GAL1–MET4 | this study |

| CC932-8B | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, met4::GAL1–MET4, met30::LEU2 | this study |

| CC954-10A | MATa, leu2, ura3, cdc7-1 | this study |

| CC954-10C | MATa, his3, leu2, ura3, cdc7-1, met4::GAL1–MET4, met30::LEU2 | this study |

| CC970-1A | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, cdc7-1, met4::GAL1–MET4 | this study |

| R31-5C | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, lys2, ura3, cbf1::TRP1 | O'Connell and Baker (1992) |

| W303-1A | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, trp1, ura3, | R.Rothstein |

| W744-1A | MATa, ade2, his3, leu2, ura3, sam1::LEU2, sam2::HIS3 | Bailis and Rothstein (1990) |

For crosses as shown in Figure 1, diploids were selected and grown for several generations in the presence of histidine to induce plasmid loss. Diploids were sporulated, and the progeny of each cross were analyzed (20 tetrads each, Figure 1B). For the crosses involving the met3Δ, met6Δ, str4Δ or the double sam1Δsam2Δ mutants with the met30Δ LexA-MET30, HIS3 strain, the progeny tetrads contained two or three viable spores, and those spores that were Leu+ (i.e. met30Δ) were also His+ (i.e. LexA-Met30). The progeny of the cross involving the met4Δ mutation showed a high number of tetrads giving rise to four viable spores (13 for a total of 20 tested tetrads) and, of 67 viable spores, 17 were found to be leucine prototrophs (i.e. met30Δ) and histidine auxotrophs (i.e. they did not harbor the pLexM30-4 plasmid). In addition, all these 17 spores were found to be tryptophan prototrophs and methionine auxotrophs, proving that they were all met4Δ. Conversely, no leucine prototroph spores that were both histidine and tryptophan auxotrophs were recovered. These results therefore suggested that met30Δ spores could be recovered if they contain the met4Δ disruption mutation. To confirm this result, a met4Δ met30Δ spore was backcrossed to a wild-type strain or to a met4Δ MET30 strain. In the former cross (CC808), only 25% of the recovered spores were leucine prototroph spores and all these spores were tryptophan prototrophs, while in the latter cross (CC809) the leucine character segregated perfectly 2+/2–.

Plasmids

To express the different Met4p derivatives from the GAL1 promoter region from an autonomous replicating plasmid, we used the pGal316 and pGal313 plasmids (Rouillon et al., 2000). They were cleaved by EcoRI and BamHI and ligated with different EcoRI–BamHI fragments encoding deleted derivatives of Met4p from the set of pLexMet4 plasmids described in Kuras and Thomas (1995). New Met4p derivatives were constructed as described in Kuras and Thomas (1995) except that the ligations were made directly in the pGal313 or pGal316 plasmids cleaved by EcoRI and BamHI (Table III).

Table III. Plasmid list.

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| pGalMet4-1 | pGal1-MET415–666, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ12 | pGal1-MET4Δ79–180, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ13 | pGal1-MET4Δ189–221, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ21 | pGal1-MET4Δ115–184, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ26 | pGal1-MET4Δ160–186, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ30 | pGal1-MET4Δ211–232, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ37 | pGal1-MET4Δ352–366, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ38 | pGal1-MET4Δ375–430, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ47 | pGal1-MET4Δ160–221, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pGalMet4Δ146 | pGal1-MET4Δ616–666, URA3, CEN | this study |

| pMT291 | CLN2HA, LEU2, CEN | Tyers laboratory |

| pMT1241 | CLN1HA, LEU2, CEN | Tyers laboratory |

| pMT485 | pGAL1-CLN1HA, LEU2, CEN | G.Tokiwa |

| pMT634 | pGAL1-CLN2HA, LEU2, URA3, CEN | Tyers laboratory |

| pCB1317 | Sc-pADH1-CLN2HA, LEU2, CEN | K.Arndt |

To integrate the GAL1–MET4 fusion gene into the genome, we first cloned the StuI–EcoRI fragment, blunt ended with Klenow fragment from plasmid pM4-1 (Thomas et al., 1992) into pGalM4-1, cleaved by Asp718, blunt ended with Klenow fragment and dephosphorylated. Since correct ligation events restored one Asp718 site, the resulting plasmid contained one Asp718–BamHI fragment corresponding to the GAL1–MET4 gene fusion flanked by 5′ and 3′ regions of the MET4 gene. Owing to the one-step gene disruption method (Rothstein, 1983), this fragment was used to replace the met4::TRP1 locus of strain CC849-8A by the GAL1–MET4 fusion gene by selecting for Met+ transformants in galactose medium. Correct integration events were verified by Southern blot analyses.

Northern blot analyses

Northern blotting was performed as described by Thomas (1980), with total cellular RNA extracted from yeast as described by Schmitt et al. (1990) and oligolabeled probes (Hodgson and Fisk, 1987).

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry analyses, cells were harvested, fixed in 70% ethanol and stained with propidium iodide as described (Mann et al., 1992).

Polysome profiles

Polysomes were isolated as described (Zhong and Arndt, 1993). Briefly, cells were grown to log phase, and 60 μg/ml cycloheximide was added for 5 min before collecting the cells. Cells were lysed in a Tris-based buffer containing heparin, and extracts were loaded onto sucrose gradients ranging from 7 to 47% sucrose, spun at 35 000 r.p.m. in an SV41 rotor for 2 h, and read at A254 via continuous drip.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Régine Barbey, Frank Sicheri and Lea Harrington for helpful assistance. D.T. was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Association de la Recherche sur le Cancer. M.T. is supported by the National Cancer Institute of Canada and the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC), and is a Scientist of the MRC of Canada. C.P. is supported by a thesis fellowship from the Ministère de l'Education, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, A.R. is supported by a thesis fellowship from the Fondation de la Recherche Médicale and E.E.P. is supported by an Ontario Graduate Scholarship studentship.

References

- Bailis A.M. and Rothstein, R. (1990) A defect in mismatch repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae stimulates ectopic recombination between homologous genes by an excision repair dependent process. Genetics, 126, 535–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaiseau P.L. and Thomas, D. (1998) Multiple transcriptional activation complexes tether the yeast activator Met4 to DNA. EMBO J., 17, 6327–6336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaiseau P.L., Isnard, A.D., Surdin-Kerjan, Y. and Thomas, D. (1997) Met31p and Met32p, two related zinc finger proteins, are involved in transcriptional regulation of yeast sulfur amino acid metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 3640–3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghino G.P. and Scheffler, I.E. (1996) Genetic analysis of glucose regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: control of transcription versus mRNA turnover. EMBO J., 15, 363–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chérest H. and Surdin-Kerjan, Y. (1992) Genetic analysis of a new mutation conferring cysteine auxotrophy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: updating of the sulfur metabolism pathway. Genetics, 130, 51–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig K.L. and Tyers, M. (1999) The F-box: a new motif for ubiquitin dependent proteolysis in cell cycle regulation and signal transduction. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol., 72, 299–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza F.H., Ogas, J., Herskowitz, I. and Morgan, D.O. (1994) Cell cycle control by a complex of the cyclin HCS26 (PCL1) and the kinase PHO85. Science, 266, 1388–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz D., St Jean, A., Woods, R.A. and Schiestl, R.H. (1992) Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 1425–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith O.W. (1987) Mammalian sulfur amino acid metabolism: an overview. Methods Enzymol., 143, 366–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. (1994) Cell cycle. cAMPing out. Nature, 371, 286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson C.P. and Fisk, R.Z. (1987) Hybridization probe size control: optimized ‘oligolabelling’. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman R.M. (1997) Methioninase: a therapeutic for diseases related to altered methionine metabolism and transmethylation: cancer, heart disease, obesity, aging and Parkinson's disease. Hum. Cell, 10, 69–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin W.G. and Maher, E.R. (1998) The VHL tumour-suppressor gene paradigm. Trends Genet., 14, 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P., Sia, R.A., Bardes, E.G., Lew, D.J. and Reed, S.I. (1998) Cdc34 and the F-box protein Met30 are required for degradation of the Cdk-inhibitory kinase Swe1. Genes Dev., 12, 2587–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinakis D.M., Schold, S.C., Jr, Hori, H. and Nobori, T. (1997) Effect of long-term depletion of plasma methionine on the growth and survival of human brain tumor xenografts in athymic mice. Nutr. Cancer, 29, 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L. and Thomas, D. (1995) Functional analysis of Met4, a yeast transcriptional activator responsive to S-adenosylmethionine. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 208–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuras L., Barbey, R. and Thomas, D. (1997) Assembly of a bZIP–bHLH transcription activation complex: formation of the yeast Cbf1–Met4–Met28 complex is regulated through Met28 stimulation of Cbf1 DNA binding. EMBO J., 16, 2441–2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo A., Cereghino, G.P. and Scheffler, I.E. (1992) Control of mRNA turnover as a mechanism of glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 2941–2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T. (1999) A ubiquitin ligase complex essential for the NF-κB, Wnt/Wingless and Hedgehog signaling pathways. Genes Dev., 13, 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann C., Micouin, J.Y., Chiannikulchai, N., Triech, I., Buhler, J.M. and Sentenac, A. (1992) RPC53 encodes a subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNA polymerase C (III) whose inactivation leads to a predominantly G1 arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 4314–4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margottin F., Bour, S.P., Durand, H., Selig, L., Benichou, S., Richard, V., Thomas, D., Strebel, K. and Benarous, R. (1998) A novel human WD protein, h-β TrCp, that interacts with HIV-1 Vpu connects CD4 to the ER degradation pathway through an F-box motif. Mol. Cell, 1, 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measday V., Moore, L., Ogas, J., Tyers, M. and Andrews, B. (1994) The PCL2 (ORFD)–PHO85 cyclin-dependent kinase complex: a cell cycle regulator in yeast. Science, 266, 1391–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash R., Tokiwa, G., Anand, S., Erickson, K. and Futcher, A.B. (1988) The WHI1+ gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae tethers cell division to cell size and is a cyclin homolog. EMBO J., 7, 4335–4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K. (1996) At the heart of the budding yeast cell cycle. Trends Genet., 12, 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell K.F. and Baker, R.E. (1992) Possible cross-regulation of phosphate and sulfate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics, 132, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura F., Fujita, A. and Shibano, Y. (1996) Single point mutations in Met4p impair the transcriptional repression of MET genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett., 387, 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee A.B. (1989) G1 events and regulation of cell proliferation. Science, 246, 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton E.E., Willems, A.R., Sa, D., Kuras, L., Thomas, D., Craig, K.L. and Tyers, M. (1998) Cdc53 is a scaffold protein for multiple Cdc34/Skp1/F-box protein complexes that regulate cell division and methionine biosynthesis in yeast. Genes Dev., 12, 692–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott C.C., Rashford, J., Yamaguchi-Iwai, Y., Rouault, T.A., Dancis, A. and Klausner, R.D. (1998) Cell-cycle arrest and inhibition of G1 cyclin translation by iron in AFT1-1(up) yeast. EMBO J., 17, 5026–5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenis M. and Schmidt, E.V. (1997) Coupling of cell division to cell growth by translational control of the G1 cyclin CLN3 in yeast. Genes Dev., 11, 2522–2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenis M. and Schmidt, E.V. (1999) Coordination of cell growth with cell division. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 9, 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R.J. (1983) One step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol., 101, 202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouillon A., Barbey, R., Patton, E.E., Tyers, M. and Thomas, D. (2000) Feedback-regulated degradation of the transcriptional activator Met4 is triggered by the SCFMet30 complex. EMBO J., 19, 282–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt M., Brown, T. and Trumpower, B. (1990) A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 3091–3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman F., Fink,G.R. and Hicks,J.B. (1979) Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sherr C.J. (1994) G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell, 79, 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman P.T., Sherlock, G., Zhang, M.Q., Iyer, V.R., Anders, K., Eisen, M.B., Brown, P.O., Botstein, D. and Futcher, B. (1998) Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 3273–3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Surdin-Kerjan, Y. (1997) Metabolism of sulfur amino acids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 61, 503–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Rothstein, R., Rosenberg, N., Surdin-Kerjan, Y. (1988) SAM2 encodes the second methionine S-adenosyl transferase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Physiology and regulation of both enzymes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 8, 5132–5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Jacquemin, I., Surdin-Kerjan, Y. (1992) MET4, a leucine zipper protein and centromere binding factor I, are both required for transcriptional activation of sulfur metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 1719–1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D., Kuras, L., Barbey, R., Chérest, H., Blaiseau, P.L., Surdin-Kerjan, Y. (1995) Met30p, a yeast transcriptional inhibitor that responds to S-adenosylmethionine, is an essential protein with WD40 repeats. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 6526–6534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P.S. (1980) Hybridization of denatured DNA and small DNA fragments transferred to nitrocellulose. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 77, 5201–5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers M. and Rottapel, R. (1999) VHL: a very hip ligase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 12230–12232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger M.W. and Hartwell, L.H. (1976) Control of cell division in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by methionyl-tRNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 73, 1664–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H.J., Loo, S. and Campbell, J.L. (1993) Regulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC7 function during the cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol., 4, 195–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong T. and Arndt, K.T. (1993) The yeast SIS1 protein, a DnaJ homolog, is required for the initiation of translation. Cell, 73, 1175–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]