Abstract

A previously unrecognized mismatch repair activity is described. Extracts of immortalized MSH2-deficient mouse fibroblasts did not correct most single base mispairs. The same extracts carried out efficient repair of A/C mismatches. A/G mispairs were less efficiently corrected and there was no significant repair of A/A. MLH1-defective mouse extracts also repaired an A/C mispair. A/C correction by Msh2–/– mouse cell extracts was not affected by antibodies against the PMS2 protein, which inhibited long-patch mismatch repair. A/C repair activity is thus independent of MutSα, MutSβ and MutLα. A/C mismatches were corrected 5-fold more efficiently by extracts of Msh2 knockout mouse cells than by comparable extracts prepared from hMSH2- or hMLH1-deficient human cells. MSH2-independent A/C correction by mouse cell extracts did not require a nick in the circular duplex DNA substrate. Repair involved replacement of the A and was associated with the resynthesis of a limited stretch of ⩽25 bases of DNA.

Keywords: A/C mispairs/mismatch repair/Msh2 knockout mice

Introduction

The post-replicative mismatch repair system prevents the accumulation of spontaneous mutations. Its primary purpose is to recognize errors in DNA replication and to eliminate them by an excision repair mechanism. Substrates for mismatch repair include DNA containing non-complementary base pairs or small unpaired loops. In mammalian cells, the initial detection of mismatches is carried out by one of two heterodimers. MutSα, the predominant recognition factor, is a dimer of the MSH2 and MSH6 proteins, which are both homologous to the MutS mismatch recognition factor of Escherichia coli. In a second, less abundant, MutSβ recognition heterodimer, MSH2 is complexed with MSH3, another MutS homologue. A subsequent step of repair is dependent on MutLα, which comprises the MLH1 and PMS2 proteins, homologues of the E.coli MutL mismatch repair protein. A characteristic feature of the post-replicative mismatch repair pathway is that removal of the mismatch is associated with the excision and synthesis of a long, up to 1000 bases, tract of DNA (for a recent review see O'Driscoll et al., 1998).

In addition to the long-patch pathway for general correction of replication errors, there are specialized repair pathways that remove specific mismatched DNA bases. A thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) removes thymine from G/T mispairs in non-replicating DNA and thereby initiates the replacement of the mismatched pyrimidine by the base excision repair pathway. TDG has a strong preference for mismatched thymine bases within CpG DNA motifs and its role is to excise the products of deamination of 5-methylcytosine. Repair in this case is associated with the removal and replacement of the single deaminated base (for a recent review see Schär and Jiricny, 1998). MYH, a mammalian homologue of the E.coli MutY protein, is another DNA glycosylase, which can also be regarded as a mismatch repair enzyme that initiates base excision repair. The substrate for MYH is adenine incorporated opposite the oxidized form of guanine [8–oxoguanine (8–oxoG)]. The A/8–oxoG pairing is highly preferred during replication and the action of MYH is expected to reduce the burden of transversion mutations, which are a common outcome of oxidative DNA damage (Michaels et al., 1992). An extensively purified MYH from calf thymus is also able to excise adenine from A/G and A/C mispairs (McGoldrick et al., 1995).

Although no human hereditary conditions have been associated with a reduced ability to perform mismatch correction by the base excision repair pathway (Lindahl et al., 1997), defects in the long-patch pathway are firmly associated with human cancer. Germline mutations, predominantly in the hMLH or hMSH2 mismatch repair genes, are associated with the familial cancer predisposition in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome. HNPCC individuals develop early-onset cancer, particularly malignancies of the colorectum and endometrium. In HNPCC tumours, the second mismatch repair allele has undergone somatic inactivation and the tumour cells do not contain detectable long-patch mismatch correction activity (reviewed in Kolodner, 1995). Inactivation of the remaining allele is probably a relatively early event and the resulting mutator phenotype undoubtedly contributes to the rapid development of the tumour.

‘Knockout’ mice bearing one or two inactive alleles of a gene have proved to be useful aids to understanding the function of a particular gene product. Knockout animals, or immortalized embryonic cell lines derived from them, occasionally exhibit unexpected phenotypes, which provide evidence of redundant or overlapping functions. Mlh1–/– and Pms2–/– mice are infertile and exhibit defects in meiosis (Baker et al., 1995, 1996; Edelmann et al., 1996). In contrast, Msh2–/– mice are fertile (de Wind et al., 1995), suggesting a partial redundancy for this mismatch repair factor. Both Msh2–/– and Mlh1–/– mice develop normally, but are tumour prone and die at an early age from lymphoma. Mice heterozygous for an inactive Msh2 do not exhibit the same spectrum of spontaneous tumours as homozygous knockout animals (de Wind et al., 1998). The tumours to which these animals succumb are not those that are characteristic of HNPCC and, significantly, tumour development is not associated with inactivation of the remaining Msh2 allele. Overall, knockout mice do not seem to be a particularly good model for HNPCC. There may be some redundancy among mismatch repair factors as well as unrecognized differences between mismatch repair in humans and in mice.

Here we report that embryonic fibroblast cell lines from Msh2–/– and Mlh1–/– mice exhibit the expected defects in long-patch mismatch correction with one important exception: these cells retain a significant activity towards A/C mispairs. A/C mismatch repair was also observed in extracts of similarly defective human tumour cell lines, but the activity was at least 5-fold lower. Repair was mismatch specific and involved a relatively short repair tract. We suggest that this previously unrecognized activity may form a back-up, or alternative pathway for A/C mismatch repair in mouse cells.

Results

MSH2/MLH1-independent A/C mismatch correction in mouse cell extracts

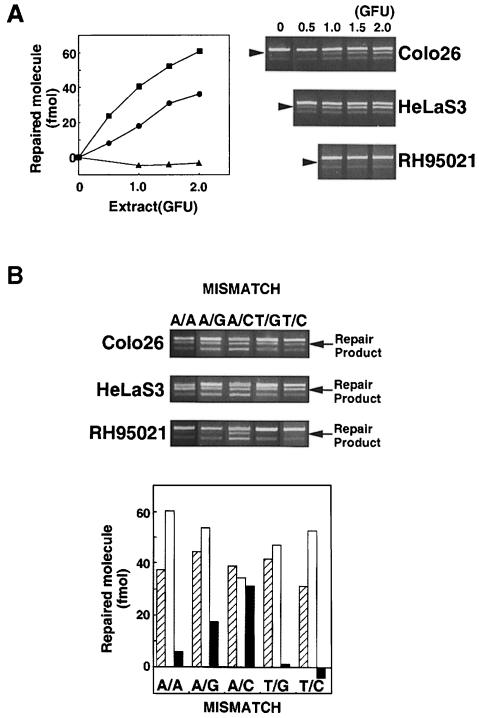

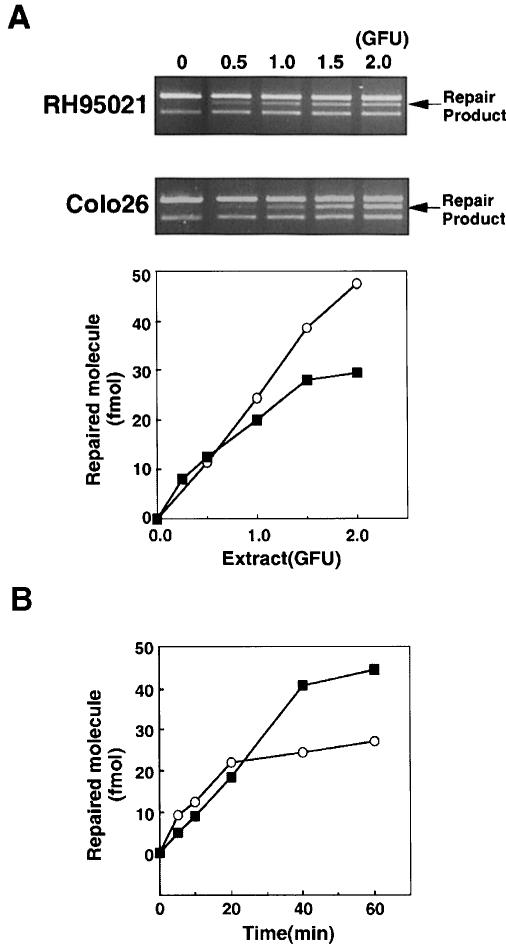

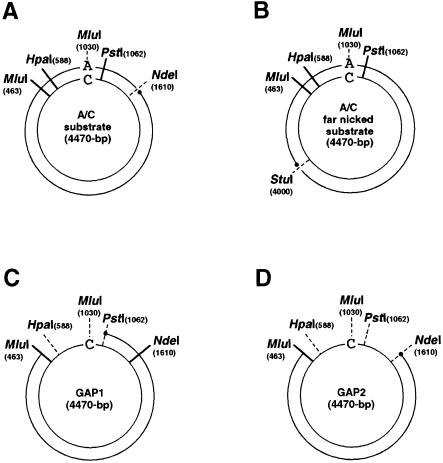

Extracts of Colo26 mouse colon tumour or human HeLa cells corrected each of the possible single base mispairs in the standard assay. Examples of the repair of T/C and other mismatches are presented in Figure 2. Extracts of RH95021 cells, immortalized embryonic fibroblasts derived from an Msh2–/– mouse, did not perform detectable repair of a T/C or T/G mismatch (Figure 2). This is consistent with the absence of the long-patch mismatch repair pathway in this Msh2–/– mouse cell line. In contrast, an A/C mispair was corrected efficiently by the same RH95021 cell extracts and the overall level of A/C repair was comparable in human HeLa and the Colo26 and RH95021 mouse cell extracts (Figure 2B). RH95021 extracts also carried out a low level of repair of an A/G mismatch. The extent of correction of an A/A mispair was close to the limit of detection by the assay (Figure 2B). Repair by RH95021 and Colo26 mouse cell extracts was comparable over a range of extract concentrations (Figure 3A) and was quite rapid with an approximate half-time of 20–30 min (Figure 3B). Thus, MSH2-defective RH95021 mouse cell extracts are able to carry out a selective and efficient correction of A/C mispairs independently of the long-patch mismatch repair pathway.

Fig. 2. Mismatch repair activity in extracts of Colo26, HeLaS3 and RH95021 cells. (A) T/C mismatch repair. Cell extracts were standardized for gap-filling activity as described in Materials and methods. The amount of extracts corresponding to the GFU indicated was incubated with the mismatched substrate (141 fmol). DNA was recovered, digested with MluI and the products separated on an agarose gel. The uppermost band is the unrepaired or incompletely repaired substrate. The repair product of 3903 bp is shown arrowed. (The lowest band represents re-annealed linearized plasmids, which do not interfere with the assay.) The amount of repair is plotted as a function of GFU for HeLaS3 (▪), Colo26 (wild-type mouse) (○) or RH95021 (Msh2–/– mouse) (▴). (B) Efficiency of correction of different mismatches by human and mouse cell extracts. Mismatch repair assays were carried out using the different mismatched substrates indicated and 1.5 GFU cell extract. After recovery of DNA and digestion with the appropriate diagnostic restriction enzyme, products were separated on agarose gels. The repair products (arrowed) were quantified as described in Materials and methods. Colo26 (□); HeLaS3 (□); RH95021 (▪).

Fig. 3. A/C mismatch repair by extracts of RH95021 cells. (A) An A/C mismatched substrate (141 fmol) was incubated for 20 min with extracts of Msh2–/– RH95021 cells corresponding to the GFU indicated. The DNA was digested with MluI and analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The repair products (arrowed) were quantified as described in Materials and methods. (B) An A/C mismatched substrate was incubated with 1.0 GFU of cell extract for the times indicated. Products were analysed and quantified as above. RH95021 (▪); Colo26 (○).

MC2 is an immortalized embryonic fibroblast line derived from an Mlh1–/– mouse. MC2 cells are defective in the MutLα component of long-patch mismatch repair. The ability to correct an A/C mismatch was compared in extracts of MC2 cells and extracts of immortalized parental wild-type embryonic fibroblasts, MC5. MC2 and MC5 cell extracts exhibited a similar proficiency in correcting A/C mismatches (Figure 4A). Both were somewhat less efficient than either Colo26 or RH95021 cells. This may reflect differences in the genetic backgrounds of the Msh2–/– and Mlh1–/– mice or the strategy used to immortalize the cells. Nevertheless, the ability of MC2 cell extracts to carry out A/C mismatch repair suggests that this correction is independent of MLH1 and of the MutLα repair complex.

Fig. 4. MSH2-independent A/C repair does not require MutLα. (A) A/C repair activity in Mlh1 nullizygous MC2 cells. A/C repair assays were carried out using extracts of MC2 (Mlh1–/–) and the parental wild-type MC5 cells. The repair products (arrowed in the gel photograph) were analysed by agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified as described in Materials and methods. MC2 (▪); MC5 (□); RH95021 (○). (B) Effects of neutralizing antibodies against PMS2 on A/C repair in extracts of RH95021 and Colo26 cells. RH95021 (▪, □) or Colo26 (•, ○) extracts were pre-incubated with the increasing amounts of IgG shown before addition of the mismatched DNA. After a standard repair reaction, products were analysed and quantified. Anti-PMS2 antibody (▪, •); non-specific IgG (□, ○).

Separate confirmation of the independence of A/C repair from MutLα was obtained by the use of a neutralizing antibody against the PMS2 component of the complex. Correction of a T/C mispair by the MSH2-dependent pathway in Colo26 extracts was inhibited when the assay was supplemented with antibody against PMS2. In contrast, MSH2-independent correction of A/C mispairs by RH95021 extracts was not significantly affected by the same range of antibody concentrations (Figure 4B). A small decrease in the extent of repair was noted, but there was no difference between the inhibitory effects of immune or pre-immune IgG. Thus, A/C mismatch repair by these mouse cell extracts is independent of both the MutSα and MutLα repair complexes.

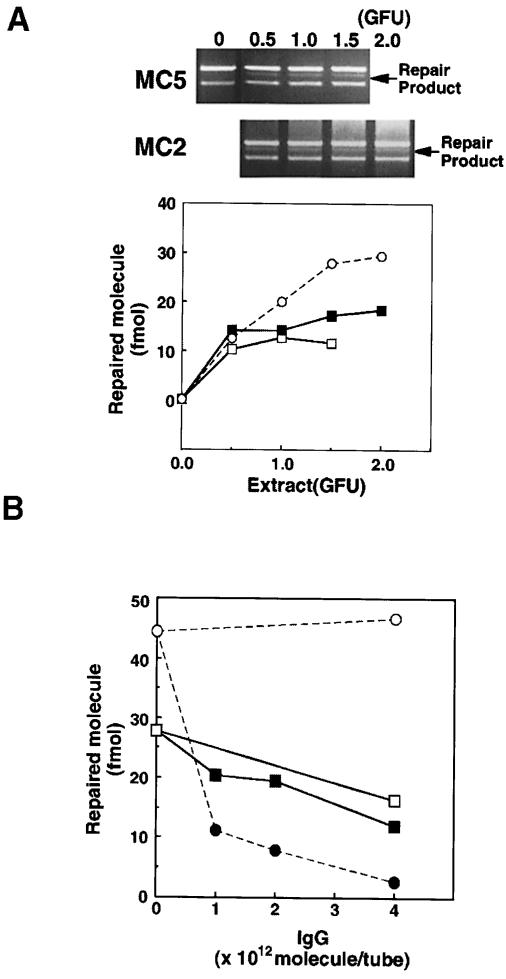

MSH2/MLH1-independent A/C mismatch repair is less active in human cell extracts

Human cells with defective long-patch mismatch repair were significantly less proficient in the repair of A/C mismatches than Msh2–/– mouse cells. Jurkat human lymphoma cells are defective in the expression of hMSH2 (Brimmel et al., 1998) and the protein is not detectable by immunoblotting. Correction of A/C mismatches by Jurkat cell extracts was inefficient. Less than 10% of the substrate was corrected by 2 gap-filling units (GFU) of Jurkat cell extract, whereas <0.5 GFU of RH95021 carried out a similar extent of correction (Figure 5). In the HCT116 human colorectal carcinoma cell line, both alleles of the hMLH1 gene are inactivated by mutation. Extracts of hMLH1-defective HCT116 cells did not perform detectable A/C mismatch correction (Figure 5). As expected, neither Jurkat nor HCT116 extracts were proficient in the correction of T/C or other mismatched substrates by long-patch, nick-directed mismatch repair (Figure 5; data not shown). The ability to carry out the gap-filling reaction was similar in Jurkat and HCT116 and the two mouse cell extracts. This serves as an internal control for the quality of the extracts. We conclude that MutSα- and MutLα-independent A/C repair activity is present in human cells, but is at least 5-fold less active than in mouse cells.

Fig. 5. A/C repair activity in long-patch mismatch repair-deficient human cell extracts. A/C and T/C mismatch repair assays were carried out using extracts of the established human cell lines Jurkat (hMSH2-defective) and HCT116 (hMLH1-defective). Products were separated and quantitated. Jurkat: A/C repair (▪), T/C repair (□); HCT116: A/C repair (▴). A/C repair by RH95021 extracts is shown for comparison (○).

MSH2-independent A/C mismatch correction is unidirectional and does not require a nick

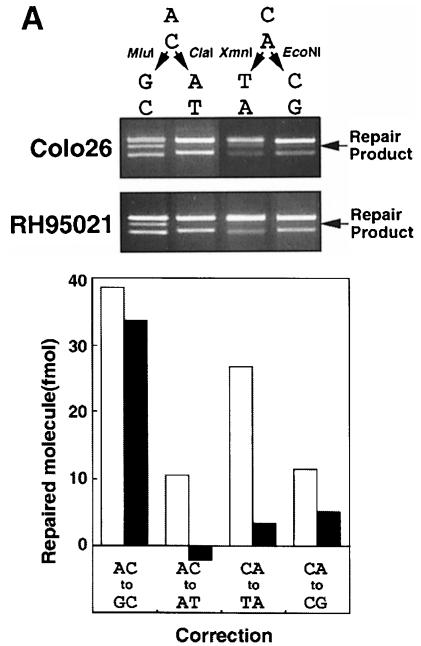

The standard heteroduplex substrate contains a nick in the A-containing strand of the A/C mispair. MSH2-independent correction of this nicked A/C mismatched substrate by RH95021 extracts was unidirectional. Correction restored a G:C base pair to generate a product sensitive to digestion by MluI (Figure 6A). It was similar in this regard to repair by the long-patch pathway in Colo26 extracts. In neither case was there detectable restoration of the ClaI restriction site, which denotes correction to A:T. RH95021 extracts were unable to correct an otherwise identical substrate in which the mispair was inverted (C/A) such that the mispaired A was in the uninterrupted strand. No correction, either to T:A or to C:G, was observed. In contrast, Colo26 extracts corrected the A/C mismatch to G:C and C/A to T:A in the expected nick-directed fashion (Figure 6A). These data suggest that the MSH2-independent mismatch repair in these mouse extracts is specific for the A of the A/C mispair, although the paucity of significant MSH2-independent correction of the C/A mispair indicates that the presence of a mismatched A is insufficient to ensure its correction and that the pathway has additional requirements.

Fig. 6. Direction of correction and nick dependency of MSH2-independent A/C mismatch repair. (A) A/C and C/A mismatch correction by RH95021 and Colo26 cell extracts. Standard substrates containing an A/C or a C/A mispair were incubated with 1 GFU of either Colo26 or RH95021 extracts. The extent of correction to either G:C or A:T was examined. The diagnostic restriction enzymes for each correction event are indicated. Products were analysed and quantified and are expressed as the extent of correction in either direction. Colo26 (□); RH95021 (▪). (B) Effects on repair of the distance of the nick from the A/C mismatch. Repair assays were carried out using the amount of extract indicated. The standard substrate (A/C standard) contained the nick 580 bp 3′ to the mispair. In the ‘far nicked’ substrate, the nick is 1500 bp on the 5′ side of the mismatch. Following incubation with the amounts of RH95021 cell extract shown, repair was quantitated and is expressed as a function of extract concentration. ‘Far nicked’ substrate (▪); standard nicked substrate (□). (C) Nicked and ligated duplexes as substrates for A/C repair by RH95021 extracts. Repair assays were carried out using the amount of extract indicated. The standard substrate, A/C nick(+), contained a nick 580 bp 3′ to the A/C mispair. Nick(–) substrates were covalently closed duplexes in which the nick had been removed by ligation with T4 DNA ligase as described in Materials and methods. Following incubation with the amounts of RH95021 cell extract shown, repair was quantitated and is expressed as a function of extract concentration. Ligated substrate (▪); standard nicked substrate (□).

The nick in the standard heteroduplex substrates is 580 bp 3′ to the mispair. Similar extents of A/C mismatch repair by RH95021 extracts were observed when the nick was moved from 580 bp 3′ to the A/C mispair to a position 1500 bp on the 5′ side (Figure 6B). Thus, in contrast to the long-patch, nick-directed pathway, the efficiency of A/C correction is not detectably diminished when the nick is distant from the mismatch.

To investigate whether a discontinuity is required for MSH2-independent A/C mismatch repair, we examined correction of a ligated A/C mismatched circular duplex. The A/C mismatch in this closed circular molecule was corrected with an efficiency comparable to that of the nicked substrate (Figure 6C). Thus, although A/C mismatch correction by the MSH2-independent pathway preferentially corrected the mismatched A in the standard nicked duplex, the presence of a discontinuity in the A-containing strand is not essential for correction. In contrast to MSH2-dependent long-patch repair, A/C correction functions efficiently in the absence of a nick.

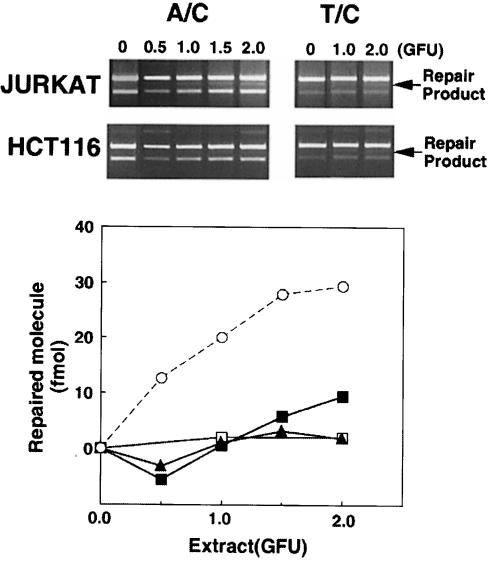

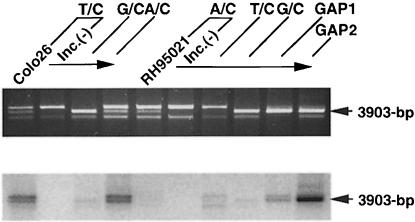

MSH2-independent A/C mismatch repair is accompanied by a short repair patch

The relative sizes of the repair patch associated with MSH2/MLH1-independent A/C correction and long-patch repair of a T/C mismatch were determined by quantifying the incorporation of radiolabelled dGMP. The gap-filling assay using the gapped substrates (Figure 1) served as a standard to quantify the level of incorporation. At comparable extents of repair, dGMP incorporation into the completed products of A/C correction by Msh2–/– RH95021 extracts was much lower than the incorporation associated with repair of a T/C mispair by Colo26 extracts (Figure 7). The estimated repair patch associated with completed MSH2-independent A/C repair corresponded to around nine guanine residues, representing an overall patch size of ∼25 bases in the G-rich local sequence. In contrast, correction of a T/C mispair by Colo26 mouse cell extracts was associated with an estimated 125 guanine residues, corresponding to a patch size of ∼500 bases. This is in good agreement with the value derived from direct inspection of the DNA sequence (143 guanines in 580 bases) if repair is initiated at the nick and proceeds by the shorter path to the mismatch. The average repair tract associated with correction of the A/C mispair by Colo26 extracts was significantly shorter: 420 bases. This is consistent with contributions by both the long- and short-patch pathways to repair of this particular mispair by the wild-type cell extracts.

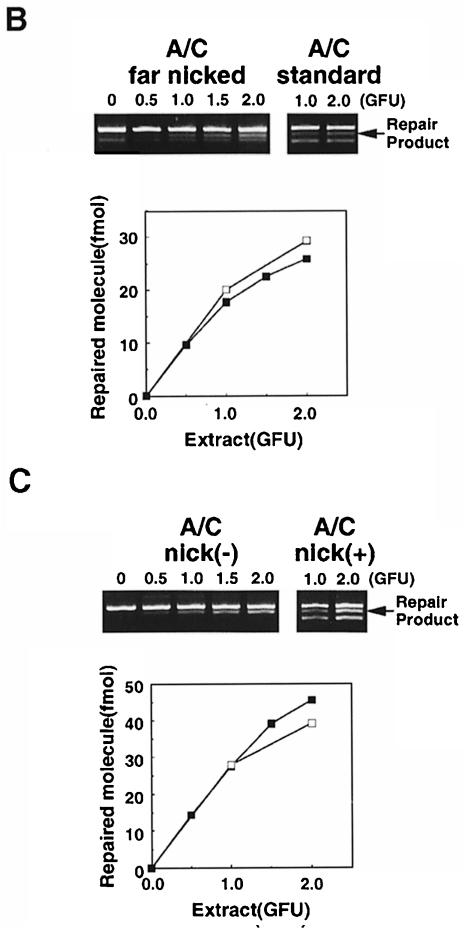

Fig. 1. Circular duplex substrates used for mismatch repair and gap-filling assays. All the circular duplex substrates used in this study were prepared by annealing linearized double-stranded plasmid DNA and single-stranded circular viral DNA. (A) The A/C substrate is shown as a representative of the standard mismatch repair substrates. (B) ‘Far nicked’ A/C mismatched substrate. The nick was moved from the standard position, 580 bp 3′ to the mismatch, to a position 1500 bp on the 5′ side. (C) The GAP1 substrate contains a 599 base gap. (D) The GAP2 substrate contains a 1147 base gap. GAP1 and GAP2 were used as standards for the gap-filling assay and for estimation of repair patch size as described in Materials and methods.

Fig. 7. Estimate of the size of repair patch accompanied by A/C repair. Each mismatched or gapped substrate was incubated with RH95021 or Colo26 cell extract in the presence of [α-32P]dGTP, recovered and digested with MluI. The relative mass corresponding to 3903 bp fragments was estimated using the Gel Doc 1000 system. Autoradiography of the same gel was performed using a PhosphorImager. From the relative mass and the radioactivity, the specific radioactivity in each band was calculated. The specific activity measurements of the 3903 bp fragments derived from G:C nick(+), GAP1 and GAP2 substrates were highly proportional to the number of guanine residues in the gaps. This linear relationship (R2 = 1.00) was used to calculate the number of incorporated dGMP residues associated with each correction event. The repair patch size was estimated based on the local DNA sequence.

The MSH2- and MLH1-independent correction of A/C mismatches is therefore mechanistically distinct from long-patch, nick-directed mismatch repair. Correction of the mispaired A to restore a G:C base pair involves replacement of a relatively short stretch of DNA: ∼25 bases. This contrasts with the ≥500 bases associated with MSH2- and MLH1-dependent correction by the long-patch pathway.

Mismatch nicking by MSH2-defective mouse extract

The short-patch mismatch repair exhibits a significant preference for A/C mispairs. An ability to nick duplex DNA at A/C mispairs is a known property of MYH, the mammalian homologue of the E.coli MutY protein. MYH is a DNA glycosylase/AP lyase that catalyses the removal of adenine bases mispaired to 8–oxoG (McGoldrick et al., 1995). We tested the ability of the repair extracts to carry out a similar mismatch-related nicking. No incision of the A-containing strand was observed when repair extracts of Colo26, Jurkat or RH95021 cells were incubated for extended periods with linear duplex oligonucleotides containing a single A/8–oxoG, A/G or A/C mismatch. In addition, post-incubation treatment with piperidine did not reveal detectable DNA glycosylase activity directed towards the A-containing strand of these mispairs. All extracts contained high levels of uracil-DNA glycosylase activity (data not shown).

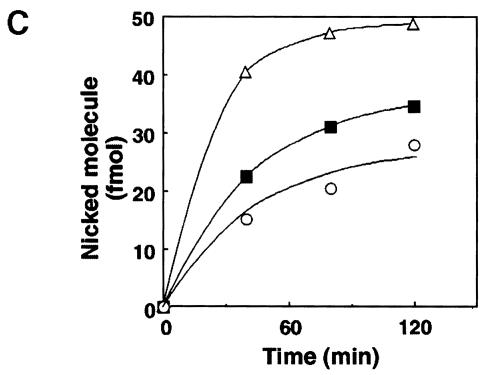

MYH activity towards an A/8–oxoG pair was detectable in cell extracts prepared by sonication. Extracts (100 μg) of RH95021 and Colo26 as well as human Jurkat cells reproducibly cleaved 5–10% of the input oligonucleotide during a 2 h incubation (Figure 8B). A/8–oxoG incision activity was similar in extracts of the MSH2-proficient and -deficient mouse and human Jurkat cells. We did not observe detectable incision or DNA glycosylase activity directed towards identical substrates in which the A/8– oxoG mispair was replaced by A/C or A/G (Figure 8A). We ascribe A/8–oxoG incision activity to the mouse and human MYH on the basis of its preferential recognition of the A/8–oxoG base pairs, which are generally regarded as the primary substrate for MutY-like activities. We note, however, that the reported preference of purified calf MYH for A/G over A/8–oxoG mispairs was not apparent in our experiments.

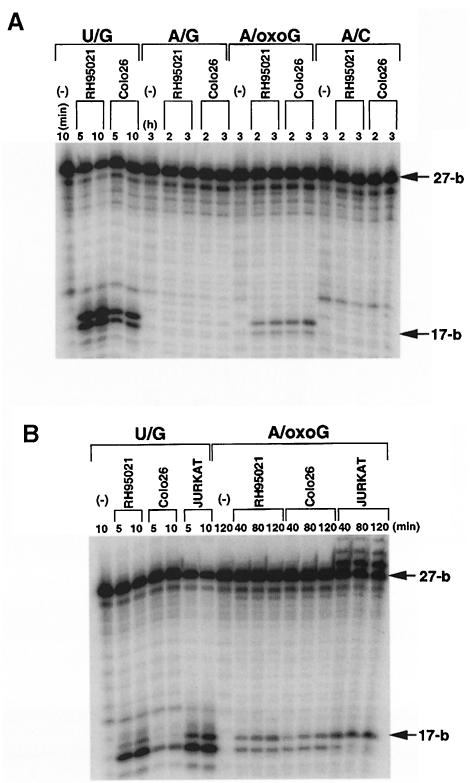

Fig. 8. Mismatch nicking by mouse and human cell extracts. Cell extracts of Colo26, RH95021 or Jurkat were prepared by sonication. A total of 500 fmol of 5′-labelled 27mer duplex linear substrates containing a unique mismatch at position 18 were incubated at 37°C with each extract for the times indicated. Incubations with the U/G substrate contained 10 μg of extract, for all other substrates 100 μg were used. The oligonucleotide was recovered and treated with piperidine. Samples were separated on 12% acrylamide–7 M urea gels and autoradiography performed by PhosphorImager. (A) Nicking activity for the mismatches indicated in RH95021 and Colo26 cell extracts. In each case, the A-containing (U–containing in the control) strand is end-labelled. (B) A/oxoG nicking activity in RH95021, Colo26 and Jurkat cell extracts. (C) The rate of nicking activity at A/oxoG base pairs determined from the digitized image of autoradiography shown in (B), using the analytical software ImageQuant. Colo26 (○); RH95021 (▪); Jurkat (▵).

Discussion

The novel A/C repair activity described here differs from the long-patch mismatch repair pathway in several respects. First, it is observed in extracts of cells derived from both Msh2 and Mlh1 knockout mice and is therefore independent of MutSα, MutSβ and MutLα. Secondly, A/C repair does not require a nick in the duplex circular substrate and instead appears to be specific for the mispaired A, although there appears to be some effect of sequence context. Thirdly, replacement of the mismatched A is associated with a much smaller repair tract with an estimated upper limit of ∼25 bases. Finally, A/C correction is ∼5-fold more active in mouse cell extracts than in extracts prepared from human cells. This is in contrast to the generally greater efficiency of the MutSα- and MutLα-dependent pathway in human cell extracts.

The existence of mismatch repair that does not require MSH2 or MLH1 is consistent with a redundancy among DNA repair pathways. The selective repair of T/G mismatches initiated by the TDG represents a specialized mismatch repair activity, which is essentially specific for a particular mispaired base and is independent of MSH2 and MLH1 (Schär and Jiricny, 1998). A/C repair may represent an analogous function. Deamination of DNA bases poses a significant threat to the cell and may provide a rationale for A/C specific repair. Thus, deamination of cytosine or 5-methylcytosine residues within mispairs generated by misincorporation of A would produce A:U or A:T pairs. Subsequent repair of A:U pairs initiated by the highly abundant uracil-DNA glycosylase would fix a C to T transition mutation. Rapid removal of the A by either the long-patch mismatch repair system or by auxiliary base-specific A/C repair would reduce the probability of the formation of A:U or A:T base pairs by deamination and thereby avoid the fixation of mutations.

In long-patch repair a strand interruption provides a general cue to designate the base for correction. Repair of a circular substrate is generally by the shortest route between it and the mismatch, and may involve replacement of a long tract of DNA (Modrich and Lahue, 1996). The nick is not required for short-patch A/C correction, in which the specificity appears to reside largely in the mismatched A. Excision and replacement of up to 1 kb of DNA is uniquely associated with long-patch mismatch repair. The short repair tract of ⩽25 bases, which is associated with MutSα- and MutLα-independent A/C repair, is compatible with correction by nucleotide excision repair. Cell extracts of the type we use for mismatch repair assays do not perform significant nucleotide excision repair, however. In confirmation of this, we found that RH95021 extracts that were fully proficient at A/C repair were unable to incise a duplex circular substate bearing a single 1,3-intrastrand d(GpTpG)–cisplatin adduct (data not shown). This lesion is an excellent substrate for incision by nucleotide excision repair proteins (Moggs et al., 1996). The extracts we used therefore appear to lack essential nucleotide excision repair factors. The short repair patch is also consistent with A/C correction by base excision repair initiated by a DNA glycosylase. Using standard repair extracts, we did not observe detectable DNA glyco– sylase activity directed towards the mispaired A, although the same extracts contained significant levels of uracil and other DNA glycosylases. Although we observed incision at an A/8–oxoG mispair by extracts prepared by a different protocol, A/G and A/C nicking activity, which is a known property of the MYH DNA glycosylase (McGoldrick et al., 1995), was undetectable. These data suggest that MutSα-independent A/C mismatch correction might not be by a recognized DNA repair pathway. We cannot, however, formally exclude participation of either base or nucleotide excision repair.

A/C repair was found to be significantly more active in mouse than in human cell extracts. There is also evidence that rodent cells may be particularly adept at A/C (and A/G) mismatch correction in vivo. Analysis of repair of single base mispairs generated as intermediates during double-strand break repair by the single-strand annealing pathway in Chinese hamster cells suggested the presence of an A/C (and A/G) mismatch correction activity, which was independent of, and somewhat less efficient than long-patch mismatch repair (Deng and Nickoloff, 1994; Miller et al., 1997). These properties are consistent with our observations that A/C mismatches can be corrected independently of the long-patch pathway and that both pathways contribute to A/C repair in wild-type mouse cell extracts. Thus, in common with a number of other activities, analysis of residual mismatch correction in extracts of mouse cells defective in long-patch MSH2- and MLH1-dependent mismatch repair reveals a possible redundancy among DNA repair pathways.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA) unless indicated otherwise. Anti-hPMS2 mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from PharMingen GmbH (Hamburg, Germany).

Cell culture and extraction

RH95021 Msh2–/–, and the MC5 (Mlh1+/+) and MC2 (Mlh1–/–) immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts were kindly provided by Dr Hein te Riele, Amsterdam Cancer Center, and Dr Michael Liskay, University of Oregon, respectively. The remaining cell lines were from the Imperial Cancer Research Fund Cell Production stocks. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

The standard repair extract was prepared as described previously (Hampson et al., 1997). Briefly, 1–5 × 109 exponentially growing cells were harvested by trypsinization and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Pelleted cells were gently resuspended in cold Hypo/sucrose buffer [20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.25 M sucrose], pelleted and gently resuspended in cold Hypo buffer (20 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.5, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT). After recentrifugation, cell pellets were kept on ice for 15 min, transferred to a chilled Dounce homogenizer and disrupted by 20–30 strokes. The suspension was clarified by centrifugation at 10 000 r.p.m. in a Sorvall SA600 rotor for 20 min followed by 50 000 r.p.m. in a Beckman TLA120 rotor for 1 h, and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at –70°C.

The sonicated extracts used in the nicking assay were prepared as follows: 107 exponentially growing cells were recovered by trypsinization and washed once with PBS. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 M NaCl and 1 mM DTT and disrupted by sonication on ice (8 × 1 s bursts) with a microprobe of a Soniprep 150 (Sanyo, Tokyo, Japan). The suspension was clarified by centrifugation (50 000 r.p.m. in a Beckman TLA120 rotor for 15 min), and the supernatant aliquoted and stored at –70°C.

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford (1976).

Plasmid substrates

Heteroduplex plasmid substrates were prepared by annealing linearized double-stranded plasmid DNA and single-stranded circular DNA as described previously (Hampson et al., 1997). The plasmids were constructed by subcloning four different ‘mismatch cassettes’, derived from a 211 bp PvuI–PstI fragment of HK7 M13 (Brooks et al., 1989), into the pBK-CMV phagemid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

To construct the standard substrates, a purified plasmid was linearized by digestion with NdeI at position 1610, denatured and annealed to an excess of single-stranded DNA to create the appropriate specific mispair. Nicked circular double-stranded DNA products were recovered from agarose gels by electroelution. The circular duplex substrates contain a single mismatch at position 1030 and a nick in the non-viral strand at position 1610, 580 bp 3′ downstream of the mismatch (Figure 1A). Most substrate preparations contained a small amount of re-annealed linearized plasmids. The restriction endonuclease digestion products of these contaminating molecules (seen as the lowest band on agarose gel analysis of the repair products) are well resolved from the diagnostic repair products and do not interfere with the assay. In the text, the first base of the mispair (e.g. A of A/C) refers to the base in the nicked, non-viral strand.

Construction of the substrate with an alternately positioned nick (far nicked substrate, Figure 1B) was identical except that the plasmid was linearized with StuI instead of NdeI.

The substrates used for the gap-filling assay were constructed in an analogous fashion. In GAP1 molecules (Figure 1C), a purified closed circular plasmid was digested with MluI and PstI, denatured and annealed to an excess of single-stranded DNA. GAP2 molecules (Figure 1D) were constructed following digestion with MluI and NdeI.

Substrates without nicks were prepared by ligation of the nick in the standard circular duplex substrates with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT and 2 mM ATP. Ligated products were repurified from agarose gels by electroelution. Preparations examined by ethidium bromide staining contained no detectable contamination of nicked molecules.

Mismatch repair assay

Reactions (25 μl) contained 30 mM HEPES–KOH pH 8.0, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.1 mM each dNTP (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), 4 mM ATP, 40 mM phosphocreatine, 1 mg of creatine phosphokinase (rabbit type I), 40 ng (141 fmol) of substrate and cell extract. Each reaction was set up in triplicate. After 20 min incubation at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 10 mM EDTA and the three independent reactions were pooled. Following proteinase K digestion and extraction with phenol–chloroform, DNA was digested with 10 U of an appropriate diagnostic restriction endonuclease for 1 h. Digested DNA was then separated on a 0.8% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and the gel was scanned by a CCD camera in the Gel Doc 1000 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The amount of DNA in each band was estimated on digitized images using Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The repair efficiency was calculated from the ratio of repaired molecules to the total amount of substrates and the background obtained from mock reactions without incubation at 37°C was subtracted.

Gap-filling assay

Gap-filling assays were used to standardize cell extracts. Gapped substrates (40 ng, 141 fmol) were incubated with 20 μg of cell extract under the same conditions as for mismatch repair assays except that the incubation time was reduced to 3 min. Gap filling was determined by restriction enzyme susceptibility and the efficiency was calculated from the ratio of fully filled molecules to the total amount of substrate. One GFU was defined as the amount of extract required to fill completely 40 ng of GAP2 molecules within 3 min.

Measurement of repair patch size

GAP1 molecules (Figure 1C) have a 599 base gap, which is bisected by the diagnostic MluI restriction site. Thirty bases of the gap lie on the 3′ and 567 bases on the 5′ side of the MluI site. Complete filling of the 3′ gap involves the incorporation of 10 guanine residues. These incorporated bases are present in the 3903 bp MluI digestion product. GAP2 molecules (Figure 1D) contain a gap of 1150 bases, of which 580 lie 3′ to the diagnostic MluI restriction site. In this case, complete filling of the 580 base gap up to the diagnostic MluI site involves the incorporation of 143 guanine residues. The GAP1 and GAP2 substrates were incubated with cell extracts in the presence of [α-32P]dGTP, recovered and digested with MluI. Digestion products were separated on an agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The relative mass of each fragment was estimated by CCD camera scanning in the Gel Doc 1000 system. Autoradiography of the same gel was performed using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). The radiolabel incorporated into the 3903 bp MluI fragment was estimated using ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics). The specific radioactivity in each band was calculated from the relative mass and the radioactivity.

Nicking assay

Oligonucleotides used for nicking assays were synthesized using an Applied Biosystems 381B automated synthesizer (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CA) and purified by gel electrophoresis. The phosphoamidite of7,8-dihydro-8-deoxyguanosine (oxoG) was purchased from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). Incision was determined using 27mer duplexes. The following sequences were used: 5′-AGCTTCCTCATCGA-G-GC– GTTTCTCGAGGTCGA-3′, 5′-AGCTTCCTCATCGA-oxoG-GCGTT– TCTCGAGGTCGA-3′ and 5′-AGCTTCCTCATCGA-C-GCGTTTCTC– GAGGTCGA-3′. In each case, the four extreme 5′ and 3′ nucleotides were protected by phosphorothioration. The oligonucleotides were annealed to appropriate complementary strands radiolabelled at their 5′ termini using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) to generate the required mismatch at position 18 of the labelled strand. Annealing was carried out in 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM NaCl and 3 mM DTT. The mixture was heated to 70°C and cooled gradually to room temperature over 1 h. The annealed duplexes were purified by ethanol precipitation and resuspended in TE buffer.

To measure mismatch nicking, cell extracts were incubated with 500 fmol of duplex oligonucleotide substrates in a 25 μl reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.6, 5 μM ZnCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1.5% glycerol. Following incubation at 37°C, oligonucleotide was purified by phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The pellet was then redissolved in 1 M piperidine and heated at 90°C for 20 min. The products were analysed on 12% acrylamide–7 M urea DNA sequencing gels. After electrophoresis, autoradiography of the dried gel was carried out using a PhosphorImager.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Drs H.te Riele and M.Liskay for providing the RH95021 and the MC2 and MC5 cell lines, respectively. We also thank Drs I.Kuraoka and R.D.Wood for help with dual-incision assays for nucleotide excision repair. The expert assistance of the Oligonucleotide Synthesis and Cell Production Units of the Imperial Cancer Research Fund is also gratefully acknowledged. S.O. was partly supported by a grant from the Naito Foundation, Japan, and O.H. by a grant under the Human Capital and Mobility Programme of the European Union.

References

- Baker S.M., et al. (1995)Male mice defective in the DNA mismatch repair gene PMS2 exhibit abnormal chromosome synapsis in meiosis. Cell, 82, 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S.M., et al. (1996)Involvement of mouse Mlh1 in DNA mismatch repair and meiotic crossing over. Nature Genet., 13, 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M.M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilising the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem., 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brimmel M., Mendiola, R., Mangion, J. and Packham, G. (1998) BAX frameshift mutations in cell lines derived from human haematopoietic malignancies are associated with resistance to apoptosis and microsatellite instability. Oncogene, 16, 1803–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks P., Dohet, C., Almouzni, G., Mechali, M. and Radman, M. (1989) Mismatch repair involving localized DNA synthesis in extracts of Xenopus eggs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 4425–4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W.P. and Nickoloff, J.A. (1994) Mismatch repair of heteroduplex DNA intermediates of extrachromosomal recombination in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 400–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wind N., Dekker, M., Berns, A., Radman, M., te Riele, H. (1995) Inactivation of the mouse Msh2 gene results in postreplicational mismatch repair deficiency, methylation tolerance, hyperrecombination and predisposition to tumorigenesis. Cell, 82, 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wind N., Dekker, M., van Rossum, A., van der Valk, M., te Riele, H. (1998) Mouse models for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer Res., 58, 248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann W., et al. (1996)Meiotic pachytene arrest in MLH-1-deficient mice. Cell, 85, 1125–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson R., Humbert, O., Macpherson, P., Aquilina, G. and Karran, P. (1997) Mismatch repair defects and O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase expression in acquired resistance to methylating agents in human cells. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 28596–28606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodner R.D. (1995) Mismatch repair: mechanisms and relation to cancer susceptibility. Trends Biochem. Sci., 20, 397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl T., Karran, P. and Wood, R.D. (1997) DNA excision repair pathways. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 7, 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick J.P., Yeh, Y.C., Solomon, M., Essigmann, J.M. and Lu, A.L. (1995) Characterization of a mammalian homolog of the Escherichia coli MutY mismatch repair protein. Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels M.L., Cruz, C., Grollman, A.P. and Miller, J.H. (1992) Evidence that MutY and MutM combine to prevent mutations by an oxidatively damaged form of guanine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 7022–7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E.M., Hough, H.L., Cho, J.W. and Nickoloff, J.A. (1997) Mismatch repair by efficient nick-directed and less efficient mismatch-specific, mechanisms in homologous recombination intermediates in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Genetics, 147, 743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modrich P. and Lahue, R. (1996) Mismatch repair in replication fidelity, genetic recombination and cancer biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 65, 101–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moggs J.G., Yarema, K.J., Essigmann, J.M. and Wood, R.D. (1996) Analysis of incision sites produced by human cell extracts and puri– fied proteins during nucleotide excision repair of a 1,3-intrastrand d(GpTpG)–cisplatin adduct. J. Biol. Chem., 271, 7177–7186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll M., Humbert, O. and Karran, P. (1998) DNA mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Mol. Biol., 12, 173–197. [Google Scholar]

- Schär P. and Jiricny, J. (1998) Eukaryotic mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Mol. Biol., 12, 199–247. [Google Scholar]