Abstract

Diabetes and the development of its complications have been associated with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) dysfunction, but causal relationships remain undetermined. With the objective of testing whether increased mtDNA mutations exacerbate the diabetic phenotype, we have compared mice heterozygous for the Akita diabetogenic mutation (Akita) with mice homozygous for the D257A mutation in mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma (Polg) or with mice having both mutations (Polg-Akita). The Polg-D257A protein is defective in proofreading and increases mtDNA mutations. At 3 mo of age, the Polg-Akita and Akita male mice were equally hyperglycemic. Unexpectedly, as the Polg-Akita males aged to 9 mo, their diabetic symptoms decreased. Thus, their hyperglycemia, hyperphagia and urine output declined significantly. The decrease in their food intake was accompanied by increased plasma leptin and decreased plasma ghrelin, while hypothalamic expression of the orexic gene, neuropeptide Y, was lower and expression of the anorexic gene, proopiomelanocortin, was higher. Testis function progressively worsened with age in the double mutants, and plasma testosterone levels in 9-mo-old Polg-Akita males were significantly reduced compared with Akita males. The hyperglycemia and hyperphagia returned in aged Polg-Akita males after testosterone administration. Hyperglycemia-associated distal tubular damage in the kidney also returned, and Polg-D257A-associated proximal tubular damage was enhanced. The mild diabetes of female Akita mice was not affected by the Polg-D257A mutation. We conclude that reduced diabetic symptoms of aging Polg-Akita males results from appetite suppression triggered by decreased testosterone associated with damage to the Leydig cells of the testis.

Diabetes mellitus is becoming increasingly common worldwide. A large body of data demonstrates links between mitochondrial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and diabetes (1, 2). Deleterious mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations have their greatest effect in cells that require high energy production, or already have high oxidative stress, including neurons, hair cells of the inner ears, heart and skeletal myocytes, pancreatic beta cells, and gut and kidney epithelial cells (3–7). Complications of diabetes also involve damage to these metabolically active cell types, leading to a hypothesis that mtDNA mutations contributes to the complications. Consistent with these findings, we have demonstrated in mice that a genetic absence of the bradykinin B2 receptor (B2R) combined with diabetes caused by the Akita mutation, Ins2C96Y, progressively increases modifications to kidney mtDNA, including 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine content, point mutations, and deletions (8, 9). The mtDNA mutations in these mice are also associated with enhanced nephropathy and senescence-related phenotypes in multiple tissues (8, 9). However, it remains unclear whether the mtDNA mutations act causally with respect to diabetes and its complications, or are consequences of these conditions.

The enzymes required for mitochondrial biogenesis are encoded in the nuclear genome, including mtDNA polymerase γ (Polg), which replicates and proofreads the mitochondrial genome. Polg is essential for life, and its complete absence leads to early embryonic death (10). An amino acid substitution, D257A, in the exonuclease domain II of Polg ablates proofreading without significantly affecting the capacity of the polymerase to replicate mtDNA (11, 12). Mice homozygous for the D257A mutation (Polg) die prematurely by 13 mo of age, displaying a series of aging-associated phenotypes due to increased random accumulations of mtDNA mutations that lead to increased apoptosis, particularly in tissues containing cells that are metabolically active (11, 12). The D257A mutation, which does not itself induce diabetes, consequently provides a tool that can be used to determine whether an increased frequency of mtDNA mutations can influence the pathophysiology of diabetes and its complications.

In the present work, we take advantage of this tool to examine the effects of the Polg-D257A mutation in mice that are diabetic because of the dominant Akita mutation (C96Y) in the Ins2 gene. The C96Y mutation prevents the formation of an important disulfide bond in insulin and leads to misfolding of the protein. The misfolded protein has impaired transport through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which triggers an ER stress reaction leading to pancreatic β-cell apoptosis (13). Males heterozygous for the Akita mutation, but not females, develop hyperglycemia begining at ≈3 wk of age and becoming progressively more severe with age. Surprisingly, our experiments show that the diabetic symptoms of Akita male mice, which also have the PolgD257A mutation (Polg-Akita), become progressively less severe after 3 mo of age. We demonstrate that the overall improvement in the diabetic phenotype of the Polg-Akita mice is at least in part due to a reduction in the Akita-induced hyperphagia triggered by a Polg-induced decrease in testis production of testosterone. Glomerular changes were mild in all of the diabetic mice. Proximal tubular damage occurred only in aged double mutant males. Distal tubular damage occurred in all hyperglycemic males.

Results

Mitochondrial Mutations in Polg-Akita Mice.

The reported median lifespan of Polg mice homozygous for Polg-D275A mutation is 13 mo, and the amount of mtDNA mutations accumulating in Polg mice has been estimated to be as high as 1 × 10−3 mutations per bp in most tissues compared with <5 × 10−4 mutations per bp in wild-type mice (11, 12, 14, 15). Because untreated Akita diabetic mice deteriorate quickly after 9 mo (16), we determined mtDNA mutation load in the liver of 9-mo-old mice, which are histologically intact at this age. As expected, the average number of base substitution per site per hundred mtDNA molecules, without correcting for errors associated with deep sequencing and heteroplasmic polymorphisms, was significantly higher in the Polg mice than in their wild-type (WT) littermates (0.425 ± 0.005 mutations per site per hundred molecules sequenced vs. 0.375 ± 0.004; P ≤ 0.001). Diabetes, again as expected, further increased base substitution rate (P < 0.001), with the Polg-Akita mice having significantly more mutations than their Akita littermates (0.557 ± 0.007 vs. 0.494 ± 0.008; P ≤ 0.001). We conclude that the mtDNA of 9-mo-old Polg-Akita mice has accumulated significantly more mutations than the mtDNA of their Akita siblings.

The expressions of mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam), mtDNA polymerase γ (Polg), and cytochrome b (CytB) have been correlated, respectively, with mitochondrial biogenesis (17), replication (18), and function (19). However, renal and hepatic gene expression of Tfam, Polg, and CytB did not differ significantly among the groups (Table S1). Similarly, mtDNA content in these tissues was not significantly different between the two genotypes (Fig. S1). We conclude that the Polg mutation did not change mitochondrial biogenesis and replication in our diabetic mice.

mtDNA damage associated with diabetes also includes an increased incidence of deletions (8, 9). However, we found no significant differences in the incidence of D-17 deletions in the liver, pancreas, kidneys, and small intestine of the Polg-Akita mice compared with the Akita mice (Fig. S1).

Improved Diabetic Symptoms in Aging Male Polg-Akita Mice.

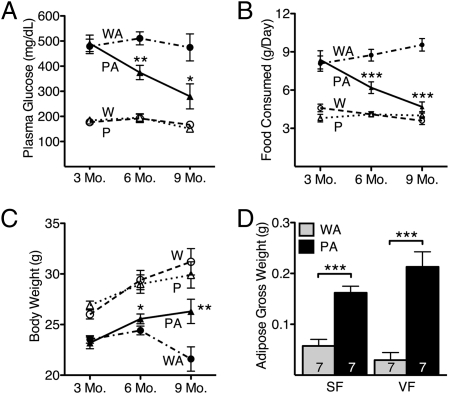

At 3 mo of age, both Akita and Polg-Akita male mice exhibited all of the symptoms normally associated with type 1 diabetes. Thus, both had markedly elevated plasma glucose levels (491 ± 33 mg/dL; Fig. 1A) and food intake (8.5 g/d; Fig. 1B) compared with their nondiabetic counterparts. In contrast, at 6 mo of age, plasma glucose and food consumption in the Polg-Akita mice began to show significant decreases relative to the Akita mice. By 9 mo of age, the fasting plasma glucose levels in the Polg-Akita mice (280 ± 50 mg/dL) had decreased still further compared with their littermate Akita mice (475 ± 54 mg/dL), although they were still significantly higher than in nondiabetic WT (167 ± 10 mg/dL) and Polg mutant (151 ± 10 mg/dL) mice. The food intake of the Polg-Akita mice was dramatically lower than that of littermate Akita mice, and was no longer different from that of nondiabetic mice. In contrast, the body weight of the Polg-Akita mice increased steadily with age, and at 9 mo, they were significantly heavier than their Akita littermates (26.3 ± 1.2 g vs. 21.6 ± 1.2 g; P ≤ 0.01, Fig. 1C). The weight gain in the Polg-Akita mice was associated with significantly larger amounts of s.c. and visceral fat (Fig. 1D), although still below the amount observed in WT mice. Diabetes in our female Akita mice was mild, as has been reported (16); it was not affected by the PolgD257A mutation (Fig. S2). Thus, plasma glucose levels are similar in Akita (276 ± 15 mg/dL) and Polg-Akita females (282 ± 20 mg/dL) through 9 mo of age. Likewise, food consumption is similar in Akita (3.78 ± 0.16 g/d) and Polg-Akita females (3.71 ± 0.27 g/d) through 9 mo of age. Together, these data show that, starting ≈3 mo of age, the PolgD257A mutation causes an age-dependent and male-specific amelioration of the Akita diabetic phenotype.

Fig. 1.

Amelioration of diabetic profiles in Polg-Akita mice. Plasma glucose (A), food consumption (B), and body weight (C) in male wild-type (W), Polg (P), Akita (WA), and Polg-Akita (PA) mice. Gross weight of s.c. (SF) and visceral (VF) fat in 9-mo-old Akita (WA) and Polg-Akita (PA) male mice (D). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 between Polg-Akita and Akita mice at each time point by the Student t test. n ≥ 20, n ≥ 10, and n ≥ 7 at 3, 6, and 9 mo, respectively.

Kidney Function.

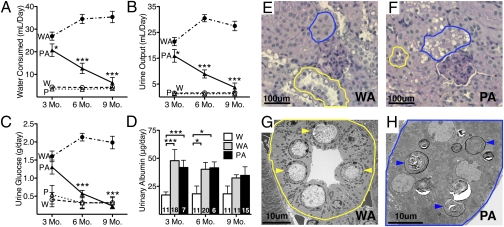

At 3 mo of age, Polg-Akita males had small but significant decreases (≈20%) in water consumption (Fig. 2A) and urine output (Fig. 2B) compared with Akita mice, although both variables were markedly higher than in nondiabetic mice. Urine glucose levels at 3 mo of age (Fig. 2C) were comparable in Polg-Akita and Akita mice. However, as the hyperglycemia of the male Polg-Akita mice improved with age, their water consumption, urine output, and urinary glucose also declined and, at 9 mo of age, they were no longer different from those of nondiabetic mice. Urinary potassium, sodium, and chloride levels did not differ in the diabetic mice regardless of the presence of the PolgD257A mutation. Despite the improvement of hyperglycemia, daily urinary albumin excretion was similar in the Polg-Akita and Akita males although it was only modestly greater than in nondiabetic males throughout the 9 mo of study (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Renal function and histology in 9-mo-old Polg-Akita mice. Water consumption (A), urine output (B), urine glucose (C), and urinary albumin (D) in wild-type (W), Polg (P), Akita (WA), and Polg-Akita (PA) mice. Renal histology of diabetic Akita (E) and Polg-Akita (F) mice with proximal tubules (blue outline) and distal tubules (yellow outline). (G) Electron micrograph of Akita distal tubular cells with glycogen deposits (yellow arrowheads) within the nuclei. (H) Electron micrograph Polg-Akita proximal tubular cells with mitochondria and lamellated inclusions (blue arrowheads) in the cytoplasm. All data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 between Polg-Akita and Akita mice at each time point by the Student t test. n ≥ 6 at 3, 6, and 9 mo.

The glomeruli showed no notable differences between the diabetic Akita mice and the Polg-Akita mice under both light microscopy (Fig. 2 E and F) or Electron microscopy (Fig. S3). No evidence of fibrosis or areas of necrosis were found. In the distal tubular epithelial cells, glycogen deposits in the central portion of nuclei were present in both the Akita and Polg-Akita kidneys, but were more prominent in the Akita mice than in Polg-Akita mice (Fig. 2 E and F, long arrows). In the proximal tubular epithelial cells, in contrast, cytoplasmic clear foamy inclusions were present only in the Polg-Akita kidneys (Fig. 2F, arrowheads), whereas no such changes were seen in either the Akita kidneys or in nondiabetic Polg kidneys of the same age. Ultrastructurally, the foamy cytoplasmic inclusions seen by light microscopy in the proximal tubular cells of the Polg-Akita kidneys proved to be markedly enlarged lysosomes containing electron-dense material and calcifications (Fig. 2H). Lamellated inclusions of glycolipids in lysosomes are correlated with increased damage and turnover of mitochondria within cells, and some inclusions can be seen in Polg-Akita kidneys, although most of the mitochondria appeared normal except for some variations in sizes and density. No inclusions were seen in the Akita littermates (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these data show that the distal renal tubular damage, which occurs in the Akita mice in association with their severe hyperglycemia, disappears in the Polg-Akita mice, in association with their markedly decreased hyperglycemia, but proximal tubular damage is now apparent because of mitochondrial damage caused by the Polg mutation.

Plasma Insulin and Insulin Sensitivity.

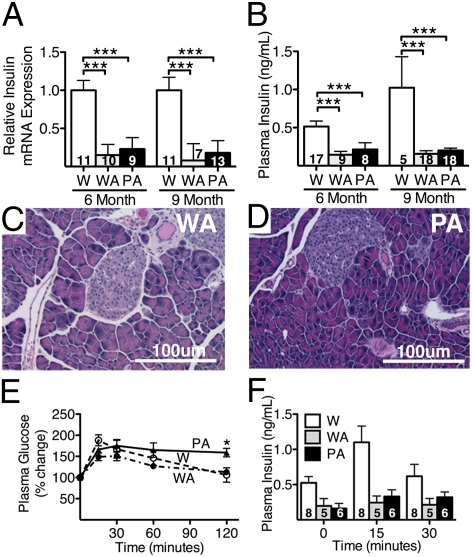

Insulin mRNA amounts in the pancreas of both Akita and Polg-Akita mice were similar, at 20–30% of the levels in nondiabetic wild-type mice (Fig. 3A). Plasma insulin levels in the Akita and Polg-Akita mice were also ≈20% of those in nondiabetic mice. Plasma insulin levels in the Polg-Akita mice were slightly higher than those in the Akita littermates, but the difference was not significant (Fig. 3B). No differences in the morphology and numbers of pancreatic islet cells were found between the Akita (Fig. 3C) and Polg-Akita (Fig. 3D) mice. At 9 mo, the Polg-Akita males exhibited impaired clearance of oral glucose loads (Fig. 3E). However, plasma insulin levels after the oral glucose challenge did not differ significantly in the Akita and Polg-Akita mice (Fig. 3F). Taken together, these data demonstrate that adding the PolgD257A mutation did not significantly change the already impaired β-cell function of the Akita mice, and that the impaired glucose handling exhibited by the Akita mice was likewise not changed by the Polg mutation.

Fig. 3.

Insulin levels in Polg-Akita and Akita mice. Insulin mRNA levels (A) and plasma insulin (B) in wild-type (W), Akita (WA), and Polg-Akita (PA) mice at 6 and 9 mo of age. All data are represented as mean ± SEM Pancreas (H&E) from 9-mo-old Akita (C) and Polg-Akita (D) mice. Glucose tolerance test (GTT) (E) and plasma insulin (F) during GTT at 9 mo of age in W, WA, and PA. **P < 0.01 between Polg-Akita and Akita, ***P < 0.001 compared with wild type by the Student t test.

Small Intestine Function.

In agreement with a previous report (11), we find that the PolgD257A mutation causes an increase in apoptosis within the villi of the small intestine of the Polg-Akita mice relative to Akita mice. Additionally, we find an increase in apoptosis and a decrease in cell proliferation in the small intestine crypts of the Polg-Akita mice relative to Akita mice (Fig. S4). However, these profiles were found at similar levels in nondiabetic Polg mice, indicating that these PolgD257A effects were not altered by diabetes. In agreement with this result, the gross morphology of the small intestine remained unchanged in 9-mo-old Polg-Akita mice relative to Akita mice. The mRNA levels of intestinal transporters that affect glucose uptake were also similar in the Polg-Akita and Akita mice (Table S2). Pancreatic expression of mRNAs for amylase, trypsinogen, chymotrypsinogen, and lipase in 9-mo-old Polg-Akita mice was not significantly affected by the PolgD257A mutation (Fig. S4). Taken together, these observations show that the Polg-Akita mice at 9 mo of age display no significant indications of digestive problems or nutrient malabsorption that might account for the amelioration of their diabetic hyperphagia and hyperglycemia.

Appetite Control.

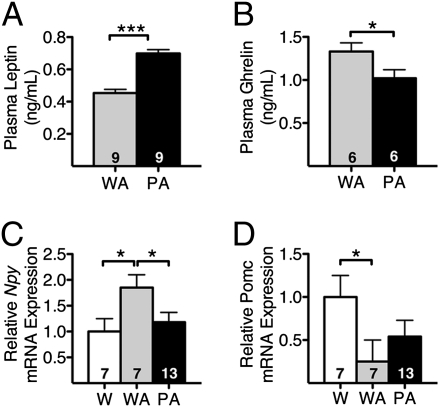

Prompted by the decrease in food consumption that developed in the Polg-Akita mice as they aged, we measured two known regulators of appetite: leptin (a suppressor of appetite) and ghrelin (a stimulator of appetite). At 9 mo of age, the plasma leptin levels in Polg-Akita mice were significantly higher (Fig. 4A), whereas circulating ghrelin levels were significantly lower, relative to Akita littermates (Fig. 4B). Expression in the hypothalamus of the anorexic gene, Pomc (coding for proopiomelanocortin), and the orexic gene, Npy (coding for Neuropeptide Y), are critical for controlling appetite (20), and we found that hypothalamic expression of the orexic Npy gene was significantly increased in Akita diabetic mice relative to nondiabetic wild-type mice (Fig. 4C), whereas expression of the anorexic Pomc gene was significantly decreased (Fig. 4D). However, in the Polg-Akita mice, these diabetes-associated shifts in Npy and Pomc expression were reversed, returning to levels not significantly different from those in nondiabetic wild-type mice. Thus, adding the PolgD257A mutation to the Akita mutation increases plasma leptin, decreases plasma ghrelin, decreases hypothalamic expression of Npy, and increases hypothalamic expression of Pomc. It is likely that these changes in modulators of food intake, all known to suppress appetite, result in the decreased appetite we observed in Polg-Akita mice relative to Akita mice.

Fig. 4.

Appetite. Plasma leptin (A), plasma ghrelin (B), and hypothalamic gene expression of Neuropeptide Y (C) and Proopiomelanocortin (D) in wild-type (W), Akita (WA), and Polg-Akita (PA) mice at 9 mo of age. All data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference by the Student t test.

Testicular Function.

The testis is severely affected by the PolgD257A mutation (11), but not by diabetes. Thus, light microscopy showed that the testes of our 9-mo-old Akita mice (Fig. 5C) were not notably different from those of nondiabetic wild-type mice (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the seminiferous tubules of the Polg (Fig. 5B) and Polg-Akita (Fig. 5D) mice were severely atrophic and contained vacuoles. Marked loss of germ cells and spermatogenesis was evident within the seminiferous tubules of both Polg and Polg-Akita mice. Light microscopy showed a significant increase in the number of Leydig cells per cluster in the Polg mice relative to WT and in the Polg-Akita mice relative to Akita, although the increase was less in the diabetic mice (Fig. 5E). Ultrastructurally, Leydig cells of the testis in Polg-Akita mice have a markedly degenerative morphology compared with Akita mice, including the presence of lipofuscin indicative of mitochondrial damage (Fig. S5).

Fig. 5.

Diminished testis function in Polg-Akita mice. Comparable histology sections of the testis of 9-mo-old wild-type (W; A) Polg (P; B), Akita (WA; C), and Polg-Akita (PA; D) mice. Total number of cells per Leydig cluster (E) and plasma testosterone (F). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference by the Student t test.

Plasma testosterone in wild-type mice at 9 mo of age was 220 ± 12 ng/dL. Plasma testosterone in the Akita mice was not demonstrably different from this value at 6 mo age, but had decreased to ≈50 ng/dL at 9 mo of age (Fig. 5F). The Polg-Akita mice had significantly lower plasma testosterone levels than the Akita mice at both ages (≈30%; P < 0.01). Together, these data demonstrate that the PolgD257A mutation has a strong and direct negative impact on testosterone levels and testicular function in the Polg-Akita mice.

Testosterone Replacement.

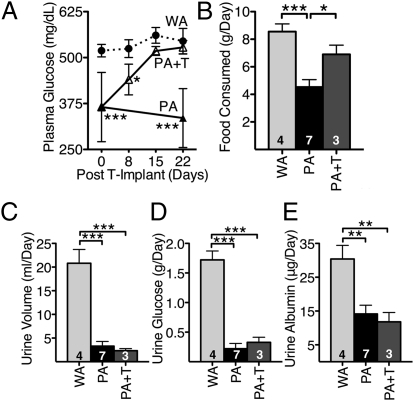

To test whether decreased testosterone levels are responsible for the reduced appetite and hyperglycemia, we implanted pellets into 6-mo-old Polg-Akita mice (n = 3) that deliver the physiological dose of testosterone (0.14 mg/d) commonly used in replacement therapy in mice (21). Within 15 d after implantation of the testosterone pellet, plasma glucose in the Polg-Akita mice increased from 300 mg/dL to 500 mg/dL, indistinguishable from the level in Akita mice without testosterone supplementation (Fig. 6A). Their food consumption also increased compared with untreated Polg-Akita mice and were essentially the same level as in untreated Akita mice (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these data show that testosterone is a key component that directly regulates food consumption and, thereby, influences the hyperglycemia of Akita male mice. Surprisingly, however, despite the return of hyperglycemia in the Polg-Akita mice treated with testosterone, their daily urine output, glucose excretion, and urine albumin excretion were not increased (Fig. 6 C–E). This result indicates that the testosterone-treated Polg-Akita mice are reabsorbing substantial amounts of glucose and suggested to us that the kidneys of these animals were likely to be metabolically stressed. In support of this idea, we found that the ultrastructure of the proximal tubules of the Polg-Akita mice treated with testosterone for 3 mo showed considerably more lamellated inclusions (Fig. S3) than were present in the untreated Polg-Akita mice of the same age (Fig. 2H).

Fig. 6.

Testosterone replacement in Polg-Akita mice. (A) Plasma glucose levels in testosterone-implanted Akita (WA+T) and Polg-Akita (PA+T) mice and Control Akita (WA or WA-T) and Polg-Akita (PA or PA-T). Food consumption (B), urine volume (C), urine albumin (D), and urine glucose (E) in WA, PA, and PA-T at 22 d after implant. All data are represented as mean ± SEM. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant difference by the Student t test.

Discussion

Because of the importance of mitochondria in metabolism, we expected that the PolgD257A mutation, which leads to an accumulation of random mtDNA mutations, would exacerbate the diabetes exhibited by male Akita mice and would increase the severity of their diabetic complications. Surprisingly, we found the opposite result: a dramatic improvement of diabetic symptoms (hyperglycemia, food consumption, and water consumption) in the Polg-Akita male mice as they aged. Accompanying these changes, we found alterations in the expression of anorexic (Pomc) and orexic (Npy) genes in the hypothalamus, indicating that the Polg mutation had caused appetite suppression. We did not find any improvement in the overall function of either the pancreas or small intestine that would be sufficient to alter the diabetes so markedly. However, there was a dramatic aging-associated increase in testicular damage in the Polg-Akita mice relative to the Akita mice, including damage to the Leydig cells, and a reduction in plasma testosterone. Testosterone replacement increased food consumption in the double mutants, and their hyperglycemia returned, confirming the influence of testosterone and appetite in the development of the diabetic symptoms of Akita male mice.

In nondiabetic animals, an increase in plasma glucose after a meal stimulates the release of insulin. Insulin binds to insulin receptors in peripheral tissues and triggers glucose uptake via insulin-sensitive glucose transporters. Insulin, together with the amylin released by the β-cells simultaneously with insulin (22), plays an important role in the regulation of appetite by suppressing orexic genes within the hypothalamus (23, 24). In Akita mice, misfolded insulin protein causes ER stress and β-cell death, resulting in reduced insulin production (13). Insufficient insulin production initiates two pathways that accelerate hyperglycemia in Akita mice (Fig. S6A). First, it reduces the ability of peripheral tissues to take up glucose. Second, the reduced insulin impairs appetite suppression in the hypothalamus causing hyperphagia. The increased food intake induces an increased demand for insulin, which increases the problems of the already stressed insulin-producing β-cells leading to further β-cell death. This damaging feedback can be partly interrupted by reducing food intake, as illustrated by the well-documented benefits of reduced food intake in the management of type 1 diabetes before the discovery of insulin (25).

In the present study, we have demonstrated that the mtDNA mutator, Polg-D257A, can break the self-induced cycle of hyperglycemia and hyperphagia of Akita male mice as they age (Fig. S6B). The most striking age-dependent damage in the Polg-Akita males is in the testis, accompanied with a decrease in circulating testosterone. Recent studies have suggested that aging-related reduction of food consumption may in part result from reduced testosterone and a consequent increase in leptin production (26). Epidemiological studies have also demonstrated an association between these factors (27). In addition, testosterone administration has been shown to suppress the elevated leptin levels in older hypogonadal men (28, 29), and dihydrotestosterone suppresses both leptin mRNA levels and leptin secretions in adipocytes in vitro (30). Leptin, produced in adipose tissues, is crucial in the regulation of appetite by signaling through the hypothalamus (31). Our observations in aged Polg-Akita males show the involvement of these factors in the changes in food consumption and appetite induced by the Polg mutation. Thus, as they age, Polg-Akita mice develop significant increases in plasma leptin, increased Pomc, and decreased Npy gene expression compared with Akita males. Furthermore, both hyperglycemia and hyperphagia returned in Polg-Akita males after testosterone administration. We conclude that the age-dependent decline of testis function and testosterone production caused by PolgD257A underlies the reduced diabetic phenotypes of the Polg-Akita mice. This interpretation is supported by a recent report that gonadectomy causes a marked reduction of hyperglycemia in diabetic Akita males and normalizes Pomc and Npy mRNA levels within their hypothalamus, and that reducing the food intake of Akita mice also reduces their hyperglycemia (20).

Testosterone increases appetite in castrated rats and appears to do so independently of its conversion to estrogen (32). Whether testosterone acts on adipocytes to regulate production of leptin, circulating leptin, or directly on the genes in the hypothalamus remains to be elucidated. In addition, because plasma testosterone levels also declined in aged diabetic Akita mice without apparent loss of appetite, other factors must be also involved. For example, a significant reduction in circulating ghrelin works in unison with the testosterone-leptin mechanism to reduce appetite. We also note that this aging-related amelioration of diabetes caused by the PolgD257A mutation could be exaggerated in the Akita model of diabetes in which β-cell destruction is directly tied to insulin production. Whether it is applicable to other animal models of diabetes remains to be determined.

The nephropathy in our experimental diabetic Akita mice was mild, in part because of their C57BL/6J genetic background, which confers resistance to diabetic nephropathy (33, 34). Concordant with the dramatic improvement of hyperglycemia and reduced urine output, the Polg-Akita mice no longer had glycogen deposits in the nuclei of their distal tubular cells. Instead, despite the lessening of their hyperglycemia, the Polg-Akita mice now had abnormalities in their proximal tubular cells. Formation of enlarged lysosomes filled with lamellated inclusions and calcifications indicate that the increase in mtDNA mutations induced by the PolgD257A mutation leads to increased mitochondrial destruction in the proximal tubular cells that have high-energy requirements and are highly packed with mitochondria. We note that diabetes is necessary to cause the observed abnormalities in the proximal tubular epithelial cells, because they were not present either in nondiabetic Polg males or in mildly diabetic Polg-Akita females of the same age. Our observation that the urine volumes and glucose excretion of testosterone-treated Polg-Akita mice remained low, despite a return of hyperglycemia, further emphasizes this interaction. Thus, the treated mice are reabsorbing sufficient amounts of filtered glucose to avoid osmotic diuresis and glycosuria even with plasma glucose levels exceeding 500 mg/dL, which requires a large amount of energy. Accompanying this high energy demand, we find an accumulation of laminated bodies in the proximal tubules of the testosterone-treated hyperglycemic Polg-Akita mice exceeding that in the euglycemic-untreated Polg-Akita mice.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the mtDNA editing mutation, PolgD257A, causes an age-dependent reduction of the diabetic phenotype of Akita male mice. We have shown that this reduction is, at least in part, due to appetite suppression caused by a premature decline in testosterone production associated with increased damage to Leydig cells. Because female Akita and Polg-Akita mice are both only moderately hyperglycemic and their food consumption remains similar throughout 9 mo of age, the Polg-D257A does not affect the severity of their diabetes. The accumulation of mitochondrial debris in the proximal tubules of the Polg-Akita males, even when euglycemic, demonstrates clearly that increased mutations in mtDNA exacerbate the kidney pathology in untreated type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Mice.

All mice were maintained on normal chow containing 5.3% fat and 0.019% cholesterol (Prolab Isopro RMH 3000, ref 5P76; Agway). The experimental animals were Akita heterozygous males homozygous for the PolgD257A mutation. Controls were male Akita littermates that were either wild type at the Polg locus (Polg+/+Akita) or heterozygous for the mutation (PolgD257A/+Akita). Heterozygous PolgD257A mutants are phenotypically indistinguishable from wild-type mice (11). Both male and female animals were monitored for diabetes and characterized at 3, 6, and 9 mo of age. The breeding process to generate doubly mutant and control mice is described in Fig. S7. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Plasma Analyses.

Animals were fasted in the morning 4 h before the collection of blood. Plasma glucose was measured by using a colorimetric kit (439–90901; Wako Chemical). Plasma levels of leptin, insulin, and ghrelin were measured by using ELISA kits (90030 and 90080; Crystal Chem and EZRGRT-91K; LINCO Research). Testosterone levels were measured in plasma pooled from 3 mice per sample with RIA kits (TKTT2; Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics) by the Reproductive Biology Core at the University of Virginia.

Mitochondrial DNA Mutations.

Mitochondria was isolated from 200 mg of liver samples pooled from 3 to 5 mice of each genotype by differential centrifugation in a sucrose gradient as described (35). DNA was purified by using standard isolation protocols and fragmented by Covaris S220 adaptive focused acoustic apparatus into 300 bp in length, and subjected to high throughput sequencing of 5,000–27,000 reads per base by using Illumina GAII. DNA sequence was processed through the bandled Solexa image extraction pipeline and aligned with ELAND software against murine mitochondrial genome sequence (NCBL Build 36) as a reference. Default quality score was adjusted to allow 2 mismatches per 36 bp reads. The uniquely mapped reads were used for further analyses.

Gene Expression.

Total RNA was purified from hypothalamus and pancreas samples by using TRIzol (15596–026; Invitrogen) as described (36). Total RNA from other tissues was purified by using an Automated Nucleic Acid Workstation ABI 6700. Real-time PCR was performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems). β-Actin mRNA was used for normalization.

Glucose Tolerance Tests.

Male mice of each genotype were fasted for 4 h before oral gavage of glucose (2 g/kg of body weight). Plasma was collected for glucose measurement at time points of 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min after gavage.

Urine Analyses.

Mice were housed in metabolic cages, allowed to acclimate to the new environment for 24 h, and urine samples were collected over a second period of 24 h. Body weight, food, and water were measured before and at the end of the second period of 24 h. Urinary Albumin and creatinine were measured by using kits (Albuwell, 1011 and Creatinine Companion, 1012; Exocell). Urinary levels of Na, K, and Cl were measured by using an Automatic Chemical Analyzer (VT250; Johnson & Johnson).

Histology.

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Paraffin sections at 5 μm were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, Periodic acid-Schiff, or Masson's Trichrome. For transmission electron microscopy (JOEL USA), small tissue fragments were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide and 1-μm-thick sections were stained with uranyl acetate followed by lead citrate.

Testosterone Replacement.

Six-month-old Polg-Akita and Akita mice were implanted with 12.5 mg/90-day testosterone time-release pellet (Innovative Research America). This dose was shown to normalize plasma testosterone levels in orchidectomized mice (21).

Data Analysis.

Values are reported as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted with JMP 6.0.2 software (SAS Institute). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. E. Wilson, K. Pandya, N. Takahashi, L. Johnson, R. Thresher, and S. Magness for advice and discussions, and Marcus McNair for skillful assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK07613, HL087946, and DK34987. R.F. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant T32-HL69768.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1106344108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.de Andrade PB, et al. Diabetes-associated mitochondrial DNA mutation A3243G impairs cellular metabolic pathways necessary for beta cell function. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1816–1826. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patti ME, Corvera S. The role of mitochondria in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:364–395. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simmons RA, Suponitsky-Kroyter I, Selak MA. Progressive accumulation of mitochondrial DNA mutations and decline in mitochondrial function lead to beta-cell failure. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28785–28791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Someya S, et al. The role of mtDNA mutations in the pathogenesis of age-related hearing loss in mice carrying a mutator DNA polymerase gamma. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1080–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trifunovic A, Larsson NG. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of ageing. J Intern Med. 2008;263:167–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in mild cognitive impairment. J Neurochem. 2006;96:825–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang D, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations activate the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and cause dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:147–157. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00695-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakoki M, et al. Senescence-associated phenotypes in Akita diabetic mice are enhanced by absence of bradykinin B2 receptors. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1302–1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI26958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kakoki M, Takahashi N, Jennette JC, Smithies O. Diabetic nephropathy is markedly enhanced in mice lacking the bradykinin B2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13302–13305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405449101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hance N, Ekstrand MI, Trifunovic A. Mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma is essential for mammalian embryogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1775–1783. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kujoth GC, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trifunovic A, et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature. 2004;429:417–423. doi: 10.1038/nature02517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, et al. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:27–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vermulst M, et al. DNA deletions and clonal mutations drive premature aging in mitochondrial mutator mice. Nat Genet. 2008;40:392–394. doi: 10.1038/ng.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vermulst M, et al. Mitochondrial point mutations do not limit the natural lifespan of mice. Nat Genet. 2007;39:540–543. doi: 10.1038/ng1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshioka M, Kayo T, Ikeda T, Koizumi A. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:887–894. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekstrand MI, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:935–944. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foury F. Cloning and sequencing of the nuclear gene MIP1 encoding the catalytic subunit of the yeast mitochondrial DNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20552–20560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blakely EL, et al. A mitochondrial cytochrome b mutation causing severe respiratory chain enzyme deficiency in humans and yeast. FEBS J. 2005;272:3583–3592. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyoshima M, et al. Dimorphic gene expression patterns of anorexigenic and orexigenic peptides in hypothalamus account male and female hyperphagia in Akita type 1 diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;352:703–708. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nathan L, et al. Testosterone inhibits early atherogenesis by conversion to estradiol: Critical role of aromatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3589–3593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051003698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore CX, Cooper GJ. Co-secretion of amylin and insulin from cultured islet beta-cells: Modulation by nutrient secretagogues, islet hormones and hypoglycemic agents. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;179:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris MJ, Nguyen T. Does neuropeptide Y contribute to the anorectic action of amylin? Peptides. 2001;22:541–546. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00348-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer CM, Belsham DD. Insulin directly regulates NPY and AgRP gene expression via the MAPK MEK/ERK signal transduction pathway in mHypoE-46 hypothalamic neurons. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;307:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westman EC, Yancy WS, Jr, Humphreys M. Dietary treatment of diabetes mellitus in the pre-insulin era (1914-1922) Perspect Biol Med. 2006;49:77–83. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2006.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morley JE. Decreased food intake with aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:81–88. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.suppl_2.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumgartner RN, et al. Serum leptin in elderly people: Associations with sex hormones, insulin, and adipose tissue volumes. Obes Res. 1999;7:141–149. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sih R, et al. Testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: A 12-month randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1661–1667. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapoor D, Clarke S, Stanworth R, Channer KS, Jones TH. The effect of testosterone replacement therapy on adipocytokines and C-reactive protein in hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:595–602. doi: 10.1530/EJE-06-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta V, et al. Effects of dihydrotestosterone on differentiation and proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells and preadipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;296:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman JM, Halaas JL. Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature. 1998;395:763–770. doi: 10.1038/27376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gentry RT, Wade GN. Androgenic control of food intake and body weight in male rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1976;90:18–25. doi: 10.1037/h0077264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurley SB, et al. Impact of genetic background on nephropathy in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F214–F222. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00204.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi Z, et al. Characterization of susceptibility of inbred mouse strains to diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2628–2637. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graham JM. Isolation of mitochondria from tissues and cells by differential centrifugation. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2001 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb0303s04. Chapter 3:Unit 3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.