Abstract

Impaired apoptosis is mediated by members of the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP) family such as survivin. Survivin was described in number of different tumors and found to correlate with poor prognosis in a variety of cancers including hematologic malignancies. The aim of this study was to determine survivin in pediatric ALL and compare it with clinical and hematological findings, response to therapy and outcome. Flowcytometry was used for detection of intracellular survivin and determine its mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in bone marrow mononuclear cells. Patients were followed up for 28 months after induction therapy. Survivin was detected in 63.3% of the patients BM. In spite of no association of survivin levels with established risk factors (P > 0.05) except with high WBC, there was significant higher level of survivin expression in high risk group patients when patients were stratified into high and standard risk groups. According to response to induction therapy, there was no significant difference, in survivin level between patients who achieved CR, RD and ED. However, patients suffering relapse of the disease, had a significant higher basal level of survivin than patients still in remission. Over expression of survivin is a candidate parameter to determine poor prognosis in ALL patients and it may serve to refine treatment stratification with intensification of therapy in those patients prone to relapse.

Keywords: Pediatric ALL, Survivin, Prognosis

Introduction

Programmed cell death is a feature of living cells, and damaged cells are eliminated in this way. Inhibitors of programmed cell death aberrantly prolong cell viability, so contributing to the occurrence and growth of tumors [1].

Apoptosis can be induced by two distinct pathways: the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway and a death-receptor-mediated extrinsic pathway. Both apoptotic pathways for caspase activation converge on downstream effector caspases commonly result in activation of the effector caspases 3 and 7 [2].

Regulation of apoptosis is delicately balanced by signaling pathways between apoptosis-promoting factors such as p53 and caspases, and antiapoptotic factors such as Bcl-2 and MDM2 [3, 4]. A group of apoptosis inhibitor molecules called inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAP) constitute a family of evolutionarily conserved apoptosis suppressors (n = 8 in humans), many of which function as endogenous inhibitors of caspases, one member of the IAP family is survivin [5].

Survivin is a bifunctional protein that suppresses apoptosis and regulates cell division [6]. Antiapoptotic properties by such regulatory gene expressions would clinically provide a significant growth advantage and disclose malignant behavior in tumors. Survivin is a unique apoptosis inhibitor and is believed to play a role in oncogenesis. [7] Survivin is switched off during fetal development and is not found in non-neoplastic adult tissues. However, it is prominently re-expressed by all the most common human cancers including cancers of the lung, genito-urinary, malignant melanoma, neuroblastoma, hepatocellular, pancreas, stomach, colon, breast cancers and soft tissue sarcomas [8, 9]. The prognostic value of survivin in hemopoietic neoplasias has not been as widely studied as in solid tumors. Although the data are limited, the prognostic value of survivin has been studied in some hemopoietic neoplasias such as high-grade lymphomas and leukemias [10, 11]. Various studies in solid tumors have revealed a correlation between survivin expression and a clinically unfavorable course of disease, suggesting that survivin expression is a poor prognostic factor [12, 13].

The results are not clear enough in hemopoietic neoplasias, but in some studies it has been found that survivin expression is a bad prognostic indicator [14].

Most chemotherapeutic agents induce tumor cell death by apoptosis [15]. Poor response to induction therapy or persistence of minimal residual disease, which is responsible for the subsequent relapse, may be caused by the resistance of leukemic blasts to induction of apoptosis. [16] So, regulation of the apoptotic or anti-apoptotic pathways is therefore, critical for disease control and also influence treatment outcome [17, 18].

Despite the very good overall prognosis of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), whose long-term survival is now 70–80%, treatment of relapsed disease remains a challenge [19]. Early identification of patients with a poor prognosis allows for the prospective evaluation of new consolidating treatment elements at an early stage of the disease. As survivin overexpression has been implicated as a poor prognostic marker in a variety of cancers including hematologic malignancies, the aim of this study was to assess the expression of survivin in bone marrow samples from de novo childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) by flowcytometry and comparing it with clinical and hematological findings, response to therapy and patients outcome.

Materials and Methods

The current study was carried out on 40 child categorized into: Group 1(study group): 30 patients with de novo ALL. They were 20 males and 10 females with a male to female ratio 2. Their ages ranged from 1 to 17 years, with median value of 4.5 years. Group 2 (controls): 10 age and sex matched non leukemic patients (most of them were ITP) to whom bone marrow aspiration was one of the required investigations. Informed consents to participate in the study were obtained by patient`s parents. ALL patients were categorized as standard risk or high risk categories. The standard risk group consists of children aged from 1 to 10 years with an initial leucocytes count of less than 50 × 109/l; all other patients were considered to have high-risk ALL [21].

Leukemia was diagnosed on the bases of:

Full history taking with emphasis on presence of leukemia associated symptoms (fever, pallor bleeding tendency, bone aches).

Thorough clinical examination was done lying stress on the presence and extent of leukemia involvement including organomegaly (liver and spleen), lymphadenopathy and CNS infiltration.

Imaging studies: Chest radiography, testicular & renal ultrasonography, echocardiogram and ECG.

Laboratory investigations including:

Complete blood count: by (Sysmex N21) automated cell counter with examination of Leishman stained peripheral blood smears.

Bone marrow aspiration with examination of Leishman stained films.

Cytochemical examination: of peripheral blood and/or bone marrow smears for myeloperoxidase.

CSF examination for blast cells.

Evaluation of liver and kidney function using (Dimension E. S. chemical autoanalyzer).

Cytogenetic analysis using G banding technique: PB and BM samples on Lithium heparin were studied by G–Banding analysis [22].

Immunophenotyping by flowcytometry (FACScan, Becton–Dickinson BD, San Diego, USA). For establishment of the diagnosis, The following labeled monoclonal antibodies were used: triple colour labeling specific markers for the three lineage groups of cells: cCD3,cCD79a and Myeloperoxidase, B-cell associated markers (CD19 and CD20), T-cell associated markers (CD3, CD5, CD7) Myeloid associated markers (CD13, CD33), monocytic marker (CD14), early markers (CD34, HLA-DR, CD10, TDT) and isotypic control markers IgG1 & IgG2a. These monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD. The samples were analyzed by CellQuest soft ware (BD). The cut-off point to consider a sample positive for a certain marker was its expression by >20% of gated cells. CD34 was considered positive when > 10% of the cells expressed the marker.

The Determination of Mean Fluorescence Intensity of Survivin Expression [23]

(Reagent provided from R&D System Inc.)

Mononuclear cells were separated from Bone marrow samples of controls and ALL patients by Ficoll Hypaque denisty gradient centrifugation (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO, USA). The separated cells washed twice using PBS and the count in the suspension was adjusted to be 5 × 106/ml.

The Intracellular staining.

Intracellular staining of survivin protein was performed as described by Kit instruction [7].

The separated cells were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFH) in PBS [0.5 ml cold PFH + 100 μl of mononuclear cells]. Tubes were incubated at 18–24°C for 10 min then cells washed twice with PBS. Permeabilization was done by adding 2 ml SAP buffer (0.1% saponin in a balanced salt solution provided by the kit) to each tube, which was centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 7 min, cell pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of SAP buffer. Ten μl of fluorescein isothiothianate (FITC) labeled anti-survivin monoclonal antibodies were added to each control and patient’s tube and 10 μl of FITC isotype negative control reagent to negative control tube. The tubes were incubated in the dark for 30 min at 18–24°C. The cells were washed twice using 2 ml of PBS buffer, then resuspended in PBS and become ready for flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometric analysis was done using CellQuest soft ware (BD). Analysis of isotypic control was done before analysis of survivin monoclonal antibodies, where the laser scatter was received on both forward and side scatter detectors to show the cell population in the basic histogram and to exclude the non specific binding.

Gating on mononuclear cells population was used for analysis of samples. Data were displayed on two histograms: Histogram I: Two-parameter histograms (FS vs. SS). Histogram II: It is usually displayed as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) value of the survivin.

Thus, a case of ALL was considered positive for survivin when MFI of their BM mononuclear cells exceeded the cut off value calculated from the BM mononuclear cells of the control group regardless of the proportion of the stained cells. A mean fluorescence intensity of (mean ± 2SD) was selected as the upper limit for normal expression.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis of data was performed with SPSS computer program (SPSS Inc., version 16.0, Chicago, IL). Data are presented as mean ± SD and median and ranges. Mann–Whitney’s test, Kruskal–Wallis, and Chi-Square tests (χ2) were done for comparison between groups (P < 0.05; significant).

Results

Survivin Expression and Calculation of Cut Off Value

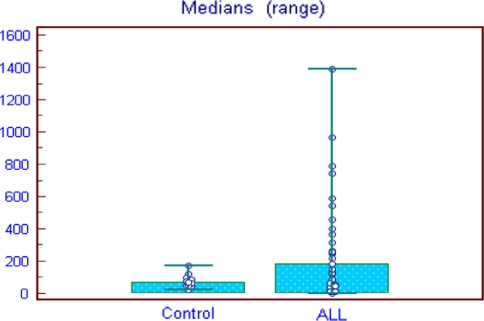

The baseline of MFI for (Group I) control was (77.40 ± 37.6), median 67.5 (Range, 0–170) and (Group II) patients was (298.96 ± 368), median 183 (Range, 0–1390). The cut off value for calculate the positive expression of survivin equals mean ± 2SD of control group expression. That equals 152.6. Survivin was homogenously low in normal BM, in contrast survivin protein expression was significantly elevated in the ALL blasts (P = 0.003) (Figs. 1, 2).

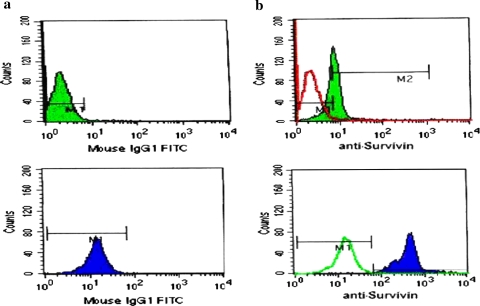

Fig. 1.

Histograms of two ALL cases, the above case: (a) shows the isotypic control, (b) the isotypic control (transparent curve) overlapped with the survivin expression in this case (opaque) (Survivin is negative). The second case: (a) shows the isotypic control, (b) the isotypic control (transparent curve) overlapped with the survivin expression in this case (opaque) (Survivin is positive)

Fig. 2.

Survivin expression among ALL patients in comparison to control Cut off value (152.6), (P = 0.003)

Survivin Association with Patients Characteristics and Risk Factors

The baseline demographic and hematological findings clinical characteristics of the patients included in this study were demonstrated according to survivin expression (Table 1). 19 (63.3%) of ALL patients showed high expression of survivin, above the cut off value while 11 (36.7%) were negative to survivin (below the upper limit of normal expression). Our study revealed that, there was no significant relation between expression of survivin on blast cells and age, sex, pallor, fever, bleeding tendency, lymph node enlargement, splenomegaly, CNS manifestation and + despin sign (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Association between survivin expression and clinical data in ALL patients

| Clinical data | Number | Survivin | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + ve (%) | −ve (%) | P-value | ||

| Age | ||||

| ≤10 years | 22 | 12 (54.5) | 10 (45.5) | 2.743 |

| ≥10 years | 8 | 7 (87.5) | 1(12.5) | NS |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 20 | 12 (60) | 8 (40) | 0.287 |

| Female | 10 | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | NS |

| Pallor | ||||

| +ve | 25 | 15 (60) | 10 (40) | 0.717 |

| −ve | 5 | 4 (75) | 1 (25) | NS |

| Fever | ||||

| +ve | 24 | 15 (62.5) | 9 (37.5) | 0.035 |

| −ve | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | NS |

| Bleeding tendancy | ||||

| +ve | 23 | 14 (60.8) | 9 (39.2) | 0.257 |

| −ve | 7 | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | NS |

| Lymph nodes | ||||

| +ve | 21 | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | 3.615 |

| −ve | 9 | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | NS |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | ||||

| +ve | 22 | 14 (63.3) | 8 (36.4) | 0.003 |

| −ve | 8 | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | NS |

| CNS manifestation | ||||

| +ve | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1.786 |

| −ve | 29 | 19 (65.5) | 10 (34.5) | NS |

| + ve despin sign | ||||

| +ve | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0.164 |

| −ve | 28 | 18 (64.3) | 10 (35.7) | NS |

NS not significant

(Table 2) as regard to Hb level and platelet count there were no significant differences between patient with high survivin expression and patients with low survivin expression according to Hb level (<10 g/dl or >10 g/dl) (P = 0.552) or Platelet count (<20 × 103/μl) or >20 × 103/μl) (P = 0.159) while there was a significant association between survivin expression and high WBCs count at diagnosis, 10 (91%) of patients presented with WBC ≥ 50 × 103/μl, were survivin positive while 1(9%) was survivin negative and 9 (47.4%) of patients presented with WBC ≤ 50 × 103/μl, were survivin Positive while 10 (52.6%) were survivin negative (P = 0.012). According to results of karyotyping, 16, 8, 3 and 3 patients showed normal karyotype, hyperdiploidy, hypodiploidy and t(9;22) respectively. The survivin expression according to patients cytogenetic is not significant (P = 0.598).

Table 2.

Association between survivin expression and laboratory data in ALL patients

| Clinical data | Number | Survivin | χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + ve (%) | −ve (%) | P-value | ||

| Cytogenetic analysis | ||||

| Normal Karyotype | 16 | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | Fisher exact test = NS |

| Hyperdiploid | 8 | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | |

| Hypodiploid | 3 | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| t(9;22) | 3 | 3 (100) | 0 (0%) | |

| Not done | 4 | – | – | |

| TLC | ||||

| ≤50 (×103/μl) | 19 | 9 (47.4) | 10 (52.6) | 6.31 |

| ≥50 (×103/μl) | 11 | 10 (91) | 1 (9) | 0.012* |

| Hb | ||||

| ≤10 (mg/dl) | 4 | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 0.353 |

| ≥10 (mg/dl) | 26 | 17 (65.4) | 9 (34.6) | NS |

| Platelets | ||||

| ≤50 (×103/μl) | 21 | 15 (71.4) | 6 (28.6) | 0.975 |

| ≥50 (×103/μl) | 9 | 4 (44.5) | 5 (55.5) | NS |

NS not significant

* Highly significant

When patient were stratified according to risk factors into two group of high risk and standard risk, survivin expression was significantly higher in patients with high risk 10 patients, (median; 374.5, range 32–1390) compared to patient with standard risk 20 patients, (median; 123, range 0–1270) (P = 0.005) (Data not shown).

In our study there was no significant association between expression of survivin and FAB classification (P = 0.10). 11 patients showed L1 morphology, 4(36.4%) were survivin positive and 7(63.6%) were negative. 14 showed L2 morphology, 11(78.6%) were survivin positive and 3(21.4%) were negative. 5 showed L3 morphology, 4(80%) were survivin positive and 1(20%) were negative (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between Survivin expression and FAB classification among ALL patients

| FAB | Number | Survivin | Fisher exact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + ve (%) | −ve (%) | |||

| L1 | 11 | 4 (36.4) | 7 (63.6) | 5.44 NS |

| L2 | 14 | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | |

| L3 | 5 | 4 (80) | 1 (20) | |

Survivin expressed as MFI were comparable between different immunophenotypes being positive in 60% of Pro-B ALL with median of 245 range (0–630), 81.9% of C-B ALL with median of 222 (0–1390), 44.4% of Pre-B ALL with median of 120 (0–1098) and mature B ALL with median of 413 (15–1270). There is no significant variation of survivin expression (MFI) (P = 0.640) or percent of positivity (P = 0.560) in different immunophenotype of childhood ALL (Table 4).

Table 4.

Association between Survivin expression and immunological classification among ALL patients

| Immunophenotyping | Number | Survivin | χ2 | MFI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + ve (%) | −ve (%) | P-value | Median (range) | |||

| Pro-B ALL | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 3.09 NS |

245 (0–630) | 0.640 NS |

| C-B ALL | 11 | 9 (81.9) | 2 (18.1) | 222 (0–1390) | ||

| Pre-B ALL | 9 | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 120 (0–1098) | ||

| Mature-B ALL | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 413 (15–270) | ||

Survivin Expression and Response to Induction Therapy

After induction therapy, 23 patients achieved CR, 14 (60.8%) were survivin positive and 9 (39.1%) were survivin negative. 5 patients showed residual disease, 3 of them (60%) were survivin positive and 2 (40%) were survivin negative and 2 had early death during induction, were survivin positive. Our result showed that there was no significant difference in MFI according to response to induction therapy (P = 0.688) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association between Survivin expression and response to therapy among ALL patients

| Clinical data | Number | Survivin | χ2 | MFI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + ve (%) | −ve (%) | P-value | Median (range) | |||

| CR | 23 | 14 (60.9) | 9 (39.1) | 0.581 NS |

156 (0–1390) | 0.688 NS |

| RD | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 413 (15–630) | ||

| ED | 2 | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 648 (27–1270) | ||

CR complete remission, RD residual disease, ED early death. P > 0.05, NS not significant

Relation Between Over Expression of Survivin and Treatment Out Come in ALL Patients

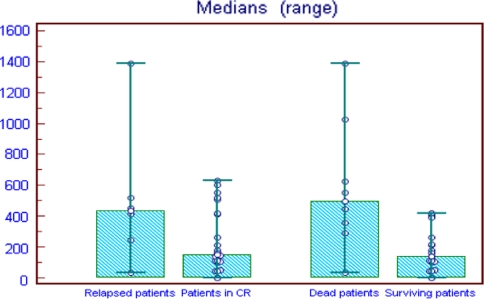

In our study we followed up the patients after induction therapy for 28 months. During follow up period 6 patients were relapsed, while 22 still in complete remission. Patients suffering relapse had significant higher basal survivin expression level (434.5; range, 31–1390) compared to those still in complete remission (153; range, 0–630) (P = 0.007). Patients who died from the disease during observation period showed significantly higher survivin expression (499; range 31–1390) than surviving patients (140.5; range, 0–420) (P = 0.011). (Table 6) (Fig. 3).

Table 6.

Survivin expression and its relevance for treatment outcome in ALL patients

| Status | Survivin expression (MFI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | ||

| Relapse | ||

| Relapsed patient (6) | 434.5 (31–1390) | 0.007* |

| Patient in CR (22) | 153 (0–630) | |

| Survival | ||

| Dead patients (8) | 499 (31–1390) | 0.011* |

| Surviving patients (20) | 140.5 (0–420) | |

* Highly significant

Fig. 3.

Survivin expression and its relevance for treatment outcome in ALL patients

Discussion

Survivin is a unique apoptosis inhibitor and is believed to play a role in oncogenesis [7].The prognostic value of survivin in hemopoietic neoplasias has not been as widely studied as in solid tumors. Although the data are limited, the prognostic value of survivin has been studied in some hemopoietic neoplasias such as high-grade lymphomas and leukemias specially AML [10, 11].

In a trial to assess the prognostic significance of survivin in precursor B childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, this study was carried out on 30 patients of de novo ALL and prior to chemotherapy. They were 20 male and 10 female. 22 (73.3%) were below age of 10 year and 8 (26.7%) above age of 10. We used flowcytometry for detection of intracellular survivin and determine its MFI on leukemic blast.

In our 30 ALL patients, expression of survivin above the background level in normal hematopoietic cells was detected in 19 (63.3%) of the patients this is similar to what was reported by Troeger et al. [20], who detect over expression of survivin in 65% of pediatric ALL patients and higher than Paydas et al. [24], who study survivin in 56 leukemia patients (37 AML and 28 ALL) they detected high survivin in 54% of the patients. Survivin expression was significantly elevated in pediatric ALL with a median MFI level of 183 (0–1390) when compared with the level in control group (P = 0.003) this in agreement with Troeger et al. [20], and with what reported previously as surviving was expressed in all AML cell lines and most of the leukemia cells and/or bone marrow cells [11]. In contrast to expression in normal tissue, survivin has been found to be over expressed in a number of different tumor tissues indicating that it has a role in carcinogenesis [14, 25].

We didn’t find any association between survivin expression and clinical data of ALL patients as; pallor, fever, bleeding tendency, lymph node enlargement, hepatosplenomegaly, CNS manifestation (P > 0.05) this is agreed with what reported previously [20, 21]. Also there was no significant association between high expression of survivin and some individual risk factors as age, Hb level, and platelet count at diagnosis. Our patients showed significant high expression of survivin in patients with WBCs ≥ 50 (×103/μl) (P = 0.012). And also there is a significant higher median level of survivin expression when the patients stratified into high risk and standard risk group with median of 374.5 (32–1390) and 123 (0–1270) respectively (P = 0.005). our finding go in agreement with that of Troeger et al. [20], who observed a trend towards a higher median level of survivin expression (575 pg/ml; range’ 0–2765 pg/ml) in high risk group than in low risk group (345 pg/ml, range 0–1589 pg/ml) (P = 0.06). However, when looking at various risk factors individually no significant difference in survivin expression level could be identified.

In keeping with the observation that survivin overexpression is a negative prognostic parameter in immature as well as mature B-cell malignancies, [14] there was no difference in survivin levels either as percent of positive cells (P = 0.56) or MFI (P = 0.640) as regards to the maturity of the B cell precursor blasts, i.e. between pro-B ALL, pre-B ALL, c-B ALL and mature B ALL. Our finding go hand in hand with that reported by Troeger et al. [20].

In spite the fact that survivin act as inhibitor to effector caspases 3/7 and blocks the mutual downstream events of both apoptosis pathways [2], survivin awards tumor resistance to apoptosis and characterizes as an ideal molecular target for therapeutic interference. Most chemotherapeutic agents induce cell death in a mitochondria-dependent manner, yet death receptor-mediated signals can also be involved. In our study we didn’t find a significant association between Survivin expression level at diagnosis and response to induction therapy (P = 0.688). Our result is the same as by Troeger et al. [20]. this may be explained by the patients who classified as high risk by standard parameters are treated more aggressively than low-risk patients which may explain why the negative effect of survivin over expression in the high-risk group is masked in the intensified treatment arm. In addition, the numbers of patients in the analysis of subgroups were small which may also influence the results.

According to outcome of therapy, 6 (20%) of ALL patient relapsed during the follow up period and the MFI of relapsed patients was significantly higher than the patients who still in remission (P = 0.007). Significantly higher survivin protein levels in patients who suffered relapse suggest that high survivin levels confer a survival advantage to blasts by inhibiting programmed cell death. Our result go in agreement with Troeger et al. [20], as in multivariate analysis on his patients, over expression of survivin was an independent risk factor for relapse associated with significantly inferior RFS.

Also in this study we compare the level of survivin expression at diagnosis in patient who died during follow up of 24 months and who still alive during this period. We detect a significant higher survivin expression in dead patient, median (499, range 31–1390) than surviving patients, median (140.5, range 0–420) (P = 0.011). Our result indicating that high survivin level is indicative of poor prognosis. This go hand in hand with Troeger et al. [20], in their retrospective study on B cell precursor ALL, over expression of survivin was an independent risk factor for inferior RFS, EFS and OS. Also in agreement with Adida et al., [14], who studied survivin using immunohistochemistry in 222 patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma, they reported that, survivin expression was found in 60% of the patients and 5-year survival was inferior in patients expressing survivin.

The findings in our study suggest that survivin over expression is a candidate parameter to determine poor prognosis in ALL patients. Survivin may, however, not only function as a risk factor discriminating patients with poor prognosis but also serve as a therapeutic target with the aim of specifically eliminating those cells that drive the disease and trigger relapse [26]. In addition to therapeutic blockage of survivin activity by antisense oligonucleotides or pharmacological inhibitors [27, 28].

References

- 1.Thompson CB. Apoptosis in the pathogenesis and treatment of disease. Science. 1995;267:1456–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.7878464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altieri DC. Validating survivin as a cancer therapeutic target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:46–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barak Y, Juven T, Haffner R, Oren M. mdm2 expression is induced by wild type p53 activity. EMBO Eur Mol Biol Organ J. 1993;12:461–468. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05678.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewski M, et al. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IPA family proteins: suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altieri DC, Marchisio PC, Marchisio PC. Survivin apoptosis: an interloper between cell death and cell proliferation in cancer. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1327–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swana HS, Grossman D, Anthony JN, et al. Tumor content of the antiapoptosis molecule survivin and recurrence of bladder cancer. Lancet. 1999;341:452–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Leung WK, Ebert MPA, et al. Increased expression of survivin in gastric cancer patients and in first degree relatives. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:91–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter BZ, Milella M, Altieri DC, Andreef M. Cytokine-regulated expression of survivin in myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:2784–2790. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.9.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mori A, Wada H, Nishimura Y, et al. Expression of the antiapoptosis gene survivin in human leukemia. Int J Hematol. 2002;75:161–165. doi: 10.1007/BF02982021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawasaki H, Altieri DC, Lu CD, et al. Inhibition of apoptosis by surviving predicts shorter survival rates in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5071–5074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adida-Adida C, Berrebi D, Paichmaur M, et al. Anti-apoptosis gene survivin, and prognosis of neuroblastoma. Lancet. 1998;351:882–883. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70294-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adida C, Haioun C, Gaulard P, et al. Prognostic significance of survivin in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2000;96:1921–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aref S, Salama O, Al-Tonbary Y, et al. Assessment of Bcl-2 expression as modulator of fas mediated apoptosis in acute leukemia. Hematology. 2004;9(2):113–121. doi: 10.1080/1024533042000205496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holleman A, Den Boer ML, Kazemier KM et al (2003) Resistance to different clases of drugs is associated with impaired apoptosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 102:4541–4546 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Schimmer AD, Hedley DW, Penn LZ, et al. Receptor and mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in acute leukemia: a translational view. Blood. 2003;98:3541–3553. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.13.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamm I, Wang Y, Sausville E, et al. IAP-family protein survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315–5320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harms DO, Janka-Schaub GE, et al. Cooperative study group for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (COALL): long-term follow-up of trials 82, 85, 89 and 92. Leukemia. 2000;14:2234–2239. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Troeger A, Siepermann M, Escherich G, et al. Survivin and its prognostic significance in pediatric acute B-cell precursor lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2007;92:1043–1050. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubnitz JE. Acute lymphoblastic Leukemia. http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2587.htm. Accessed 7 Nov 2009

- 22.Seabright M. A rapid banding technique for human chromosomes. Lancet. 1971;30:971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)90287-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid I, Uittenbogaart CH, Giorgi JV. A gentle fixation and permeabilization method for combined cell surface and intracellular staining with improved precision in DNA quantification. Cytometry. 1991;12(3):274–285. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990120312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paydas S, Tanriverdi K, Yavuz S, et al. survivin and aven: two distinct antiapoptotic signals in acute leukemias. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:1045–1050. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li F, Ambrosini G, Chu EY, et al. Control of apoptosis and mitotic spindle checkpoint by survivin. Nature. 1998;396:580–584. doi: 10.1038/25141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holleman A, Boer ML, Menezes RX, et al. The expression of 70 apoptosis genes in relation to lineage, genetic subtype, cellular drug resistance, and outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:769–776. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashibara T, Yamada Y, Nakayama S, et al. Resveratrol induces down regulation in surviving expression and apoptosis in HTLV- 1-infected cell lines: a prospective agent for adult T cell leukemia chemotherapy. Nutr Cancer. 2002;44:193–201. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4402_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter BZ, Wang RY, Schober WD, et al. Targeting survivin expression induces cell proliferation defect and subsequent cell death involving mitochondrial pathway in myeloid leukemic cells. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:488–493. doi: 10.4161/cc.2.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]