Abstract

Blood is life. Transfusion of blood and blood components, as a specialized modality of patient management saves millions of lives worldwide each year and reduce morbidity. It is well known that blood transfusion is associated with a large number of complications, some are only trivial and others are potentially life threatening, demanding for meticulous pretransfusion testing and screening particularly for transfusion transmissible infections (TTI). These TTI are a threat to blood safety. The priority objective of BTS is thus to ensure safety, adequacy, accessibility and efficiency of blood supply at all levels. The objective of the present study was to assess the prevalence and trend of transfusion transmitted infections (TTI) among voluntary and replacement donors in the Department of Blood bank and transfusion Medicine of JSS College Hospital, a teaching hospital of Mysore during the period from 2004 to 2008. A retrospective review of donors record covering the period between 2004 and 2008 at the blood bank, JSS Hospital, Mysore was carried out. All samples were screened for HIV, HBsAg, HCV, syphilis and malaria. Of the 39,060, 25,303 (64.78%) were voluntary donors and the remaining 13,757 (35.22%) were replacement donors. The overall prevalence of HIV, HbsAg, HCV and syphilis were 0.44, 1.27, 0.23 and 0.28%, respectively. No blood donor tested showed positivity for malarial parasite. Majority were voluntary donors with male preponderance. In all the markers tested there was increased prevalence of TTI among the replacement donors as compared to voluntary donors. With the implementation of strict donor criteria and use of sensitive screening tests, it may be possible to reduce the incidence of TTI in the Indian scenario.

Keywords: Transfusion transmitted infection, Human immunodeficiency virus, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus, Syphilis, Malaria

Introduction

Blood transfusion service (BTS) is an integral and indispensable part of the healthcare system. The priority objective of BTS is to ensure safety, adequacy, accessibility and efficiency of blood supply at all levels [1]. Transfusion of blood and blood components, as a specialized modality of patient management saves millions of lives worldwide each year and reduces morbidity. It is well known that blood transfusion is associated with a large number of complications, some are only trivial and others are potentially life threatening, demanding for meticulous pretransfusion testing and screening. Use of unscreened blood transfusion keep the patient at risk of acquiring many transfusion transmitted infections (TTI) like hepatitis viruses (HBV, HCV),human immune deficiency viruses (HIV), syphilis, malaria etc. Transfusion departments have always been a major portal to screen, monitor and control infections transmitted by blood transfusion. Blood transfusion departments not only screen TTI but also give clue about the prevalence of these infections in healthy populations [2].

We report the trends in the detected sero prevalence of hepatitis B(HBV), hepatitis C(HCV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), syphils and malaria over a period of 5 years from 2004 to 2008 in a tertiary care hospital based study. This provides information regarding the safety of blood transfusion and an accurate assessment of known risks versus benefits of blood transfusion [3].

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of donors record covering the period between 2004 and 2008 at the regional blood transfusion centre (RBTC), JSS Hospital serving Mysore district was carried out. Care was taken to eliminate professional donors by taking history and clinical examination. All samples were screened for HIV, HBsAg, HCV, syphilis and malaria. Serological assays for HIV, HbsAg and HCV were done by manually read ELISA procedure using 3rd generation kits (SPAN Co.). VDRL tests was done for syphilis. One step, rapid, immunochromatographic test was done for detection of plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium vivax antigen.

Results

A total of 39,060 apparently healthy adult donors were screened during the study period. Among them 38,215 (97.84%) were males and 845 (2.16%) were females. 25,303 (64.78%) were voluntary donors (VD) while 13,757 (35.22%) were replacement donors (RD) (Table 1). The overall prevalence of HIV, HbsAg, HCV and syphilis were 0.44, 1.27, 0.23 and 0.28%, respectively (Table 2). No blood donor tested showed positivity for malarial parasite. The prevalence of HIV, HbsAg, HCV and syphilis among replacement donors were 0.54, 1.23, 0.23 and 0.32%, respectively, while in voluntary donors it was 0.36, 1.22, 0.20 and 0.25%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 1.

Total blood collection and sex distribution of donors

| Year | Total donors | Voluntary donors | Replacement donors | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 6856 | 4157 | 2699 | 6690 | 166 |

| 2005 | 6789 | 4096 | 2693 | 6647 | 142 |

| 2006 | 7588 | 5402 | 2186 | 7435 | 153 |

| 2007 | 8879 | 7587 | 1292 | 8623 | 256 |

| 2008 | 8948 | 4061 | 4887 | 8820 | 128 |

| Total | 39060 | 25303 (64.78%) | 13757 (35.22%) | 38215 (97.84%) | 845 (2.16%) |

Table 2.

Incidence of HIV, HBsAg, HCV and syphilis in blood donors

| Year | Total donors | HIV | HBsAg | HCV | VDRL reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 6856 | 40 (0.58%) | 82 (1.2%) | 10 (0.15%) | 1 (0.015%) |

| 2005 | 6789 | 38 (0.55%) | 86 (1.27%) | 7 (0.10%) | 23 (0.34%) |

| 2006 | 7588 | 34 (0.44%) | 101 (1.33%) | 23 (0.30%) | 23 (0.30%) |

| 2007 | 8879 | 28 (0.32%) | 124 (1.4%) | 33 (0.37%) | 38 (0.43%) |

| 2008 | 8948 | 30 (0.34%) | 104 (1.16%) | 17 (0.19%) | 26 (0.29%) |

| Total | 39060 | 170 (0.44%) | 497 (1.27%) | 90 (0.23%) | 111 (0.28%) |

Table 3.

Incidence of TTI (%) amongst voluntary (V) and replacement (R) donors during 5 year period (2004–2008)

| Year | HIV | HbsAg | HVC | VDRL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V (%) | R (%) | V (%) | R (%) | V (%) | R (%) | V (%) | R (%) | |

| 2004 | 0.55 | 0.63 | 1.3 | 1.04 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0 |

| 2005 | 0.36 | 0.85 | 1.32 | 1.18 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.32 | 0.37 |

| 2006 | 0.43 | 0.50 | 1.36 | 1.24 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.32 |

| 2007 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 1.16 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.54 |

| 2008 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 0.69 | 1.55 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.35 |

| Average | 0.36 | 0.54 | 1.22 | 1.23 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.32 |

| Chi-square (χ2) | 10.17 | 7.352 | 13.207 | 4.475 | 15.319 | 9.304 | 15.168 | 11.583 |

| P value | 0.038 | 0.118 | 0.010 | 0.346 | 0.004 | 0.054 | 0.004 | 0.021 |

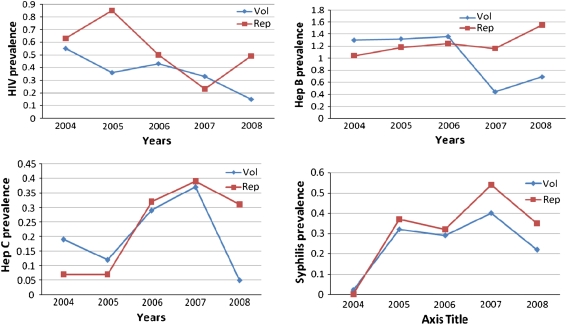

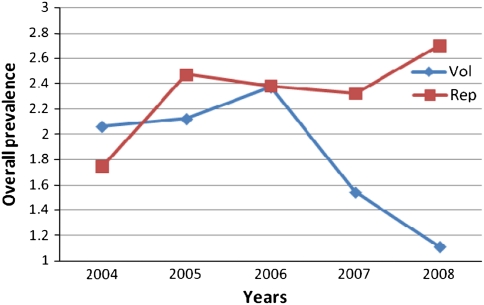

The trends in the seroprevalence of HIV, HbsAg, HCV and syphilis over the 5 year period are shown in Fig. 1. Seropositivity of HIV has decreased both in VD and RD from 0.55 to 0.15% (P 0.038) and 0.63 to 0.49% (P 0.118) respectively. Prevalence of Hepatitis B has decreased, amongst voluntary donors from 1.3 to 0.69% (P 0.010) but amongst the replacement donors a slight increasing trend is noted when compared to VD (1.04–1.55%, P-0.346). The seropositivity for anti-HCV has decreased amongst VD from 0.19% in 2004 to 0.05% in 2008 (P 0.004) but in RD, there is an increase in reactivity rate from 0.07% in 2004 to 0.31% in 2008 (P 0.054). The VDRL reactivity has shown increasing trends amongst both the VD (P 0.004) and RD (P 0.021). No blood donors tested showed positive for malarial parasite. In all the markers tested, there was an increased positivity rate among the RD’s as compared to the VD’s (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Trends in the prevalence of HIV, HbsAg, HCV and syphilis among blood donors

Fig. 2.

Trends in the prevalence of TTI among voluntary and replacement donors

Discussion

With every unit of blood, there is 1% chance of transfusion associated problems including TTI [4]. The risk of TTI has declined dramatically in high income nations over the past two decades, primarily because of extraordinary success in preventing HIV and other established transfusion transmitted viruses from entering the blood supply [5]. But the same may not hold good for the developing countries. The national policy for blood transfusion services in our country is of recent origin and the transfusion services are hospital based and fragmented [6].

The majority (97.87%) of the donors in our study were males which is comparable to the studies done by others. They are Rao and Annapurna et al. [7] in Pune, Rose et al. [8] in Vellor, Arora D et al. [4] in Southern Haryana, Singh K et al. [9] in Coastal Karnataka, Pahuja et al. [10] in Delhi and Singh B et al. [11] noting more than 90% of the male donors.

Voluntary donors (VD) are motivated blood donors who donates blood at regular intervals and replacement donors (RD) are usually one time blood donors who donates blood only when a relative is in need of blood [12]. In the present study, of the total blood donors VD constituted 64.78%, while RD were 35.22%. This is comparable to the study done by Bhattacharya et al. [13] who has noticed a predominance of VD. In contrast, a predominance of RD was noted by Singh et al. (82.4%) [11], Kakkar et al. (94.7%) [14], Singh et al. (84.43) [9], Pahuja et al. (99.48%) [10] and Arora et al. (68.6%)[4]. It is shown that replacement donors constitute the largest group of blood donors in India [15], reflecting the lack of awareness amongst the general population. Studies [9–11] have showed high seropositivity rate in RD compared to VD, a similar findings was noted in our study. Chandra et al. [16] have found almost negligible infectivity rate in VD and also no VD was found to be positive for HIV by Arora D et al. [4]. People are unlikely to become VD’s unless they receive accurate information about blood donation for which voluntary blood donation camps have to be encouraged [4].

The overall seroprevalence of HIV, HBsAg, HCV and Syphilis were 0.44, 1.27, 0.23 and 0.28%. The data providing a picture of TTI burden in India has come from various seroprevalence studies (Table 4). Serosurveys are one of the primary methods to determine the prevalence of TTI. The assessment helps in determining the safety of blood products and also gives an idea of the epidemiology of these diseases in the community [9].

Table 4.

Comparison of TTI prevalence rate in different parts of India

| Place | HIV (%) | HBsAg (%) | HCV (%) | Syphilis (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ludhiana | 0.084 | 0.66 | 1.09 | 0.85 | [22] |

| Delhi | 0.56 | 2.23 | 0.66 | [10] | |

| Lucknow (UP) | 0.23 | 1.96 | 0.85 | 0.01 | [16] |

| Southern Haryana | 0.3 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | [4] |

| West Bengal | 0.28 | 1.46 | 0.31 | 0.72 | [13] |

| Bangalore, Karnataka | 0.44 | 1.86 | 1.02 | 1.6 | [20] |

| Present study | 0.44 | 1.27 | 0.23 | 0.28 |

For HIV, India is second only to South Africa in terms of overall number of people living with HIV. The Indian National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) suggested an overall prevalence of 0.91% (2005) in India with 0.25% in Delhi [10]. The prevalence of HIV in various parts of India is different with high rate in western and southern parts [11]. Western India has reported an HIV seroprevalence of 0.47% [17], while that in Punjab it is 0.26% [18]. Sonwane et al. [19] have reported a prevalence of 1.83% in rural population. The present study showed a HIV prevalence of 0.44%. Similarly, Srikrishna et al. [20] have noted 0.44%, Pahuja et al. [10] have noted 0.56 and Singh et al. [11] have noted 0.54% of HIV seroprevalence. A WHO report states that the viral dose in HIV transmission through blood is so large that one HIV positive transfusion leads to death, on an average, after 2 years in children and after three to 5 years in adults [4]. Hence, safe transfusion practices like avoidance of single donors and practices of autologous blood transfusion should be encouraged. [11]

India has been placed in the intermediate zone of prevalence of hepatitis B by the World Health Organization (2–7% prevalence rates) with a HbsAg prevalence rate of 1–2% reported by Lodha et al. [10]. Supporting this, HbsAg prevalence in Punjab blood donors was 1.7% [18], while Rajasthan had 3.44% [21] and Delhi had 2.23% [10]. In Karnataka, coastal area [9] had 0.62% and Bangalore [20] had 1.86% of HBV seropositivity. Singh et al. have reported a HbsAg prevalence of 1.8% whereas Joshi and Ghimere have reported a prevalence of 2.71% in healthy Nepalese males [10]. Prevalence of HbsAg in our blood donors was 1.27% comparable to study done by Sri Krishna et al. [20] in Bangalore. On the other hand, the prevalence of HBV infection is lower in the United States and Western Europe (0.1–0.5%) and is reported to be higher, 5–15% in South East Asia and China [10]. Bhattacharya [13] explored a high rate of occult HBV infection prevalence among HbsAg negative/anti-HBC positive donors and thus emphasized the need for a more sensitive and stringent screening algorithm for blood donations. Gupta et al. [22] have also found more anti HBC positivity than HbsAg suggesting the ability to detect hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in window period. India is still in the intermediate prevalence zone for HbsAg and has been estimated to be a home to over 40 million HbsAg carriers. Despite the fact that a safe and effective vaccine has been available since 1982, the HbsAg prevalence in India remains high. This is because hepatitis B vaccination is not a part of our national immunization programme [10].

The wide variations of HCV seroprevalance in different studies in India might be due to the use of different generation of ELISA test kits, having different sensitivities and specificities [10]. Among the studies done, Garg et al. [21] have reported an HCV prevalence of 0.28% in blood donors of Western India and similar low prevalence of 0.23% has been noted in our study. Similar studies by Sri Krishna et al. [20] have noted a prevalence of 1.02%, Sood et al. and Pahuja et al. have reported a high prevalence of 2.2 and 2.23% in Delhi, respectively [10]. Added to this, HCV prevalence by Kaur et al. [18] was 0.78%, Singh et al. was 0.5% and Jain et al. it was 1.57% in New Delhi voluntary blood donors [10]. Internationally, various studies [10] have reported an HCV prevalence range of 0.42–1.2%.

Sexually transmitted infections are widespread is developing countries and constitute a major public health problem. The VDRL reactivity in our study was 0.28%, a comparatively low value when compared to 1.6% noted by SriKrishna et al. [20] and 2.6% by Singh et al. [11] in Delhi. Arora [4] have reported a 0.9% of VDRL reactivity while Bhattacharya [13] found 0.72% reactivity. Syphilis has also acquired a new potential for morbidity and mortality through association with increased risk of HIV infection, thus making safe blood more difficult to get. Studies related to this, Gupta et al. [22], Otuonye et al. [23] and Patil et al. [24] have observed a definite correlation between positivity of HIV and syphilis. There is no correlation between HIV and other infections noted in our study. Therefore, serological screening for syphilis serves as a surrogate test for HIV infected donors. A strict selection criteria for blood donors to exclude those with multiple sexual partners is recommended and all the affected donors should be treated appropriately [25].

In our study the prevalence of TTI showed a decreasing trend among VD, a similar finding was noted by Singh et al. [11] in VDRL reactivity. Pahuja et al. [10] have also noted a decreasing trend in the prevalence of TTI. In contrast, Bhattacharya [13] have reported a significant increase in the TTI seroprevalence.

The major concern in transfusion services today is increased seropositivity among RD for HCV, HIV, HBsAg and syphilis. With the advent of nucleic acid amplification techniques (NAT), western countries have decreased the risk of TTI to a major extent [10]. This will decrease the window period and hence decrease the incidence of TTI. But the cost-effectiveness of NAT is poor [3]. The NAT has added benefits but its high financial cost is of concern, especially in economically restricted countries. Along with advanced technology such as NAT for donor screening, other factors such as public awareness, vigilance of errors, educational and motivational programs, help in decreasing the infection [10].

Conclusion

Our study showed that most of the donors were voluntary donors with male preponderance. In all the markers tested there was increased positivity rate amongst the replacement donors as compared to the voluntary donors. Based on these results non remunerated and repeat voluntary blood donor services are needed. There should be an establishment of a nationally coordinated blood transfusion services. All blood should be tested for compatibility and TTI’s with reduction in unnecessary blood transfusion. Thus ensuring safe blood supply to the recipients. With the implementation of strict donor selection criteria, use of sensitive screening tests and establishment of strict guidelines for blood transfusion it may be possible to reduce the incidence of TTI in the Indian scenario.

References

- 1.Islam MB. Blood transfusion services in Bangladesh. Asian J Transf Sci. 2009;3:108–110. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.53880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan ZT, Asim S, Tariz Z, Ehsan IA, Malik RA, Ashfaq B, et al. Prevalence of Transfusion transmitted infections in healthy blood donors in Rawalpindi District, Pakistan–a five year study. Int J Pathol. 2007;5:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiavetta JA, Escobar M, Newman A, He Y, Driezen P, et al. Incidence and estimated rates of residual risk for HIV, hepatitis C, hepatitis B and human T-cell lymphotropic viruses in blood donors in Canada, 1990–2000. CMAJ. 2003;169:767–773. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arora D, Arora B, Khetarpal A. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in blood donors in Southern Haryana. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:308–309. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.64295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiebig EW, Busch MP. Emerging infections in transfusion medicine. Clin Lab Med. 2004;24:797–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta PK, Kumar H, Basannar DR, Jaiprakash M. Transfusion transmitted in infections in armed forces: prevalence and trends. MJAFI. 2006;62:348–350. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(06)80105-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao P, Annapurna K. HIV status of blood donors and patients admitted in KEM hospital, Pune. Ind J Hemat Blood Transf. 1994;12:174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolly R, Annie S, Thaiyanayaki P, George PB, Jacob TH. Increasing prevalence of HIV antibody among blood donors monitored over 9 years in blood bank. Indian J Med Res. 1998;108:42–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh K, Bhat S, Shastry S. Trend in seroprevalence of Hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors of coastal Karnataka, India. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:376–379. doi: 10.3855/jidc.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pahuja S, Sharma M, Baitha B, Jain M. Prevalence and trends of markers of hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus and humany immunodeficiency virus in Delhi blood donors. A hospital based study. Jpn J Inf Dis. 2007;60:389–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh B, Verma M, Kotru M, Verma K, Batra M. Prevalence of HIV and VDRL seropositivity in blood donors of Delhi. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:234–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matee MJ, Magesa PM, Lyamuya E. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B and C viruses and syphilis infections among blood donors at the Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar ES Salaem, Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhattacharya P, Chakraborty S, Basu SK. Significant increase in HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections among blood donors in West Bengal, Eastern India 2004–2005. Exploratory screening reveals high frequency of occult HBV infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3730–3733. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i27.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kakkar N, Kaur R, Dhanoa J. voluntary donors–need for a second look. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2004;47:381–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makroo RN, Salil P, Vashist RP, Lal S. Trends of HIV infection in blood donors of Delhi. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra T, Kumar A, Gupta A. Prevalence of transfusion transmitted infections in blood donors: an Indian experience. Trop Doct. 2009;39:152–154. doi: 10.1258/td.2008.080330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi SR. Seropositivity status for HIV infection among voluntary and replacement blood donors in the city of Surat from Western India. Indian J Hemat Blood Transf. 1988;16:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur H, Dhanoa J, Pawar G. Hepatitis C infection amongst blood donors in Punjab–a six year study. India J Hemat Blood transf. 2001;19:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonwane BR, Birare SD, Kulkarni PV. Prevalence of seroreactivity among blood donors in rural population. Indian Med Sci. 2003;57:405–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srikrishna A, Sitalakshmi S, Damodar P. How safe are our safe donors. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1999;42:411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg S, Mathur DR, Gard DK. Comparison of seropositivity of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in replacement and voluntary blood donors in western India. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44:409–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta N, Kumar V, Kaur A. Seroprevalence of HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis in voluntary blood donors. Indian J Med Sci. 2004;58:255–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otuonye NM, Olukoya DK, Odunukwe WN, Idigbe EO, Udeaja MN, et al. HIV association with conventional STDs (sexual transmitted diseases) in lagos state, Nigeria. West Afr J Med. 2002;21:153–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patil AV, Pawar SD, Pratinidhi AK. Study of prevalence, trend and correlation between infectious disease markers of blood donors. Ind J Hemat blood transf. 1996;14:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olokoba AB, Olokoba LB, Salawu FK, et al. Syphilis in voluntary blood donors in North-Eastern Nigeria. Eur J Sci Res. 2009;31:335–340. [Google Scholar]