Abstract

Anemia is a common concern in older people and can have significant morbidity and mortality. Because anemia is a sign, not a diagnosis, an evaluation is almost always warranted to identify the underlying cause. The purpose of this study was to study the clinical profile of elderly patients with anemia and to study characteristics of hematological types of anemia in such patients as well as the closest possible etiological profile. Hundred patients above the age of 60 years were included in the study. Clinical profile with laboratory studies of Hemoglobin and diagnostic tests to fix the etiology. Majority of patients had normocytic blood picture. Renal failure was the most common underlying chronic disease. Significant number of patients were on non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs which could contribute to the anaemia. 14% of the patients had an underlying malignancy. 73.3% of the patients in the microcytic group had an underlying GI lesion on endoscopy. Identifying anemia as an important aspect of a comprehensive geriatric assessment is absolutely essential further to clinical detection. Confirming the type of anemia is critical to direct the investigation for profiling the etiology since it is well known that the treatment of anemia goes a long way in improving the overall outcome and quality of life.

Keywords: Anemia, Geriatric, Fe deficiency, Anemia of chronic disease, Etiology

Introduction

Anemia is a common concern in geriatric age group. In this population, it can have significantly more severe complications than in the younger adults and can greatly hamper the quality of life [1].

The prevalence of anemia has been found to range from 8 to 44% [2] with highest prevalence in men who are 85 years and older. NHANES-III of WHO study revealed prevalence of anemia as 11% of men and 10.2% of women aged 65 years and older [3].

Multiple pathophysiologic abnormalities in a single patient are well known. Rectification of any of these abnormalities contributes significantly to overall improved outcome with respect to physiological parameters as well as quality of life [4].

This prospective study was conducted to study the clinical profile of anemia in elderly patients and to study the hematological types and possible etiologies of anemia in such patients.

Patients and Methods

The study was approved by the local ethics committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study.

An observational study was carried out on a cohort of patients aged 60 years and above (either sex) presenting to our hospital fulfilling the WHO criteria of anemia (hemoglobin (Hb) <13 in males, Hb <12 in females) [5]. The study was carried out over a period of 3 years. A total of 100 patients were studied. The patient selection was random and non consecutive. Microcytic anemia was defined as MCV below 80 fl, normocytic as MCV between 80 and 100 fl and macrocytic anemia by an MCV above 100 fl [6].

The symptom analysis of anemic patients was done. Patients were also analysed based upon underlying co morbid conditions, dietary habits, medication usage and presence of parasites and blood in the stool.

The following hematological investigations were carried out for all patients—Hb, total leucocyte count (TLC), differential leucocyte count (DLC), erythrocytic sedimentation rate (ESR), platelet count, blood urea, serum creatinine, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), packed cell volume (PCV), reticulocyte count, peripheral smear for blood picture and serum ferritin. Bone marrow studies (aspiration/biopsy) were carried out in patients with blood smear showing immature white cells or nucleated red cells, indeterminate status of iron stores and unexplained progressive or unresponsive anemia. Vitamin B12 and folate assays were done for dimorphic and macrocytic anemia or in patients with normocytic or microcytic blood picture in whom no other cause could be found. Additional investigations as indicated for detection of underlying cause-chest X-ray, ultrasonography (USG) of abdomen and pelvis, stool for parasites and occult blood, upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and colonoscopy, serum electrophoresis, tissue biopsy, imaging-computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), anti nuclear antibodies (ANAs). An upper GI endoscopy was carried out in all patients with iron deficiency. Colonoscopy was carried out in above set of patients in whom endoscopy did not reveal anything significant. An endoscopy was also done in patients in whom stool occult blood was positive, or an underlying cause could not be evaluated. Patients were also evaluated for an underlying malignancy if there was suspicion of the same, based on clinical symptoms, laboratory parameters or imaging studies. Hence, patients were classified according to the underlying etiology.

Results

In our study population, age of patients ranged from 60 to 87 years. The mean age was found to be 70.51 years. The maximum numbers of patients were in the age group 60–69 years. 52% were males and 42% females.

Fatigue was the most common symptom, found in 74% of patients. Palpitations and anorexia were the next common symptoms which were present in 13% patients. Breathlessness on exertion was present in 11%. Patients also had overlapping symptoms amongst these. Pallor was detectable in 59% patients, peripheral edema in 20 and 2% had significant lymphadenopathy. Glossitis was present in 1%. In our study a total of nine patients had symptoms of congestive heart failure (CHF) on presentation. A total of two patients had hepatomegaly (one had CHF and other had colonic malignancy with liver metastasis) and one patient had hepatosplenomegaly (was diagnosed with Chronic lymphocytic leukemia).

It was found that 39% of the patients were on some form of medication, the most common medication being some form of non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (71%).

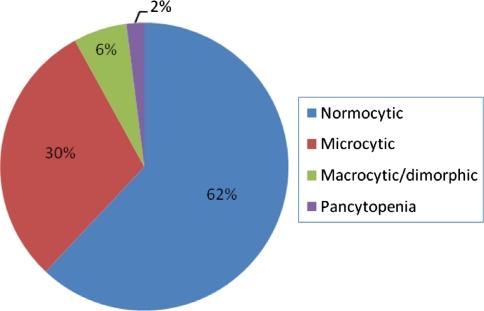

Anemia characterization on peripheral smear showed that the most common type of anemia was normocytic as is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Anemia characterization based on peripheral smear findings

Microcytic Anemia

30/100 patients had microcytic anemia. 13/30 patients were vegetarians and 17/30 predominantly were on a non vegetarian diet.

25 patients had no underlying disease and 5 had underlying osteoarthritis.

Stool analysis in the microcytic anemic patients revealed that 17 (77.3%) out of the 30 patients had positive stool occult blood test. Parasitic infestation (hookworm) was found in one patient.

Serum ferritin levels were estimated in all patients having a microcytic blood picture. Total of 11 out of 30 patients had serum ferritin values <20 ng/ml (absolute iron deficiency), 3 patients had no evidence of iron deficiency having ferritin values >100 ng/ml and 16 patients had varying degree of iron deficiency (with ferritin values between 20 and 100 ng/ml).

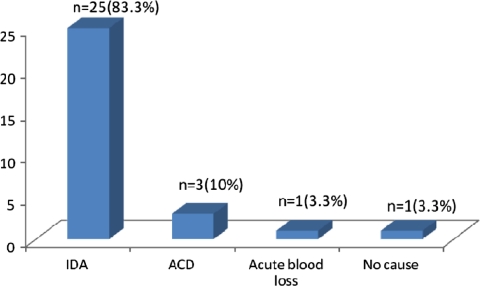

Figure 2 depicts that majority of the patients had iron deficiency anemia (IDA) (ferritin values <100 ng/ml), which was followed by anemia of chronic disease (ACD).

Fig. 2.

Pattern of anemia in the microcytic blood picture group

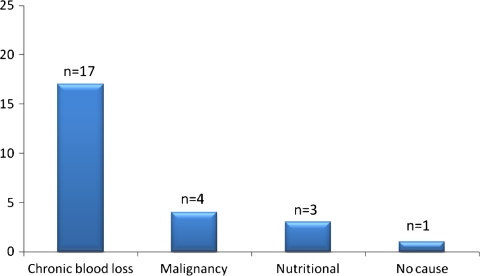

Further analysis revealed the most common cause of iron deficiency to be chronic blood loss through the gastrointestinal tract, followed by an underlying malignancy as depicted by Fig. 3. Other causes in the iron deficient group were nutritional and no cause could be identified in one patient.

Fig. 3.

Identifiable etiology in iron deficiency anemia in the microcytic group of elderly patients

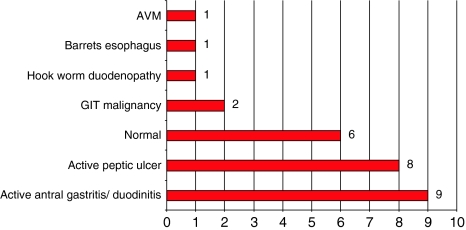

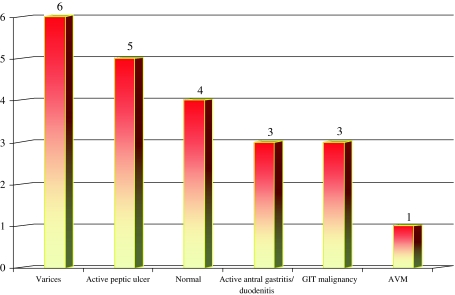

Endoscopic evaluation findings are summarised in Fig. 4 and Table 1.

Fig. 4.

Findings of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the microcytic group. Two patients did not undergo upper gastrointestinal evaluation

Table 1.

Colonoscopic findings in selected patients in microcytic group

| Normal | 12 |

| Bleeding colonic polyp | 2 |

| Malignancy | 1 |

| Hemorrhoids | 1 |

| Colitis | 1 |

Normocytic Anemia

62 patients of the total of 100 patients had normocytic anemia. 32 patients were vegetarians and 30 out of 62 were predominantly on a non vegetarian diet.

49 of these patients had no underlying disease. Four of the 62 patients had underlying osteoarthritis, 5 patients had tuberculosis and 2 had underlying rheumatoid arthritis.

Five (80%) out of the 62 patients had positive stool occult blood test. None of the patients had serum ferritin values <20 ng/ml and 55 patients had no evidence of iron deficiency, having ferritin values >100 ng/ml.

Analysis of the patients depending on the underlying etiological condition revealed that majority of the patients had anemia of chronic disease. Other etiologies which were diagnosed in these patients were 14 patients had history of blood loss, 5 elderly were found to be iron deficient and no cause was found in 1 patient.

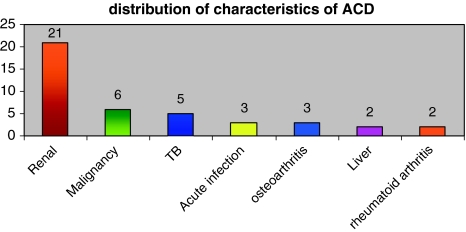

Analysis of patients with anemia of chronic disease is depicted in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of patients with anemia of chronic disease group revealed an underlying renal disease to be the most common finding followed by an underlying malignancy

Figure 6 and Table 2 show the findings of gastrointestinal evaluation for the patients who were iron deficient or had occult blood in the stool.

Fig. 6.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy findings in iron deficient patients/patients with stool occult blood in the normocytic group

Table 2.

Colonoscopic findings in normocytic group

| Normal | 9 |

| Hemorrhoids | 2 |

| Malignancy | 1 |

Macrocytic Anemia

Six patients of the total of 100 patients had macrocytic anemia. All the patients were vegetarians. None of the patients had any underlying disease.

None of the patients had positive stool occult blood test. Serum ferritin levels in all patients had values >100 ng/ml.

The characteristics of macrocytic group was as follows. Three out of the six patients had vitamin B12 deficiency, two patients had folate deficiency and one patient had anemia of chronic disease.

Pancytopenia

There were two patients who were in the pancytopenic group. Both the patients had underlying malignancy. One patient had myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and the other had acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML).

Certain additional observations made were: 22 out of the total 100 patients had deranged renal parameters. 21 out of the 22 patients had normocytic blood picture and 1 had microcytic picture. The range of serum creatinine was from 1.8 to 14.4 mg/dl. The mean creatinine value for all patients was 1.9. The mean creatinine value among those with renal dysfunction was 5.3. Out of these, 16 patients were diabetic and two were hypertensive, hence 18 out of 22 patients had deranged renal function was attributable to medical renal disease. Two patients had acute renal failure. One patient had history of chronic NSAID abuse and one had post renal transplant nephropathy.

It was also found that 14% of the patients had an underlying malignancy. Normocytic anemia was the most common blood picture in patients having an underlying malignancy. Microcytic anemia was the next common picture followed by two patients who had pancytopenic picture and one patient had macrocytic picture.

Table 3 depicts the various underlying malignancies which were diagnosed subsequent to admission.

Table 3.

Malignancies detected in the anemic elderlies

| Causes | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | 7 | 50.0 |

| Hematological | 6 | 42.0 |

| Prostatic | 1 | 8.0 |

| Total | 14 | 100.0 |

Discussion

The most common cause of anemia worldwide in elderly is anemia of chronic disease [7]. Iron deficiency is frequently seen in elderly, typically as a result of chronic blood loss through GIT [6]. Vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency, MDS are among other causes of anemia in elderly [8].

Literature has revealed that ageing does have an effect on blood production with reduced ratio of bone marrow to fat cells and reduced marrow response when stimulated with erythropoietin [9]. However, the decline of hemoglobin and concomitant increased anemia with age should not be presumed to be a result of “normal aging” or due to nutritional deficiency and blanket treatment with hematinics should be avoided. Detection of anemia in an older person should prompt appropriate clinical attention.

The serum ferritin level is the most effective way to diagnose iron deficiency anemia. When serum ferritin is <20 ng/ml, iron deficiency is virtually certain [10]. Iron deficiency is unlikely if ferritin level is >100 ng/ml (pmol/l). Ferritin levels between 20 and 100 ng/ml are moderately predictive of iron deficiency anemia.

Macrocytic anemia is described as anemia with MCV >100 fl [7]. MCV increases slightly with increasing age but usually not enough to produce significant macrocytosis. The two common disorders that produce macrocytosis are megaloblastic anemias due to either vitamin B12 or folate deficiency.

In our study, normocytic anemia was the most prevalent anemia in both the sexes accounting for 62%, which corroborates with the study done by Elis et al. [11] and Ania et al. [3].

In our study, 11% of the total patients had depleted iron stores with 66% of patients having normal iron stores. Milman and Schultz-Larsen has shown that 2.4% of anemic elderly had values <15 μg/l (depleted iron stores), 3.5% had values >30 μg/l. (small iron stores), 94.1% had values >30 μg/l [12]. This difference in the population having iron deficiency in our study could be explained on the basis of decreased dietary iron intake in Indian population.

In our study, 34% of men had iron deficiency. Milman and Schultz-Larsen has shown iron deficiency anemia was seen in 39% of men [12]. This tallies with our study observations. None of the women had iron deficiency anemia. Whereas in our study, 25% of females had iron deficiency which again could be explained due to difference in the dietary and socioeconomic patterns.

48% of all the cases in our study were anemia of chronic disease with renal insufficiency (45.8%) being the most common underlying cause in anemia of chronic disease which is consistent with various epidemiological studies [13, 14].

22% of the patients in our study were found to have to renal failure. Jack and co-workers revealed anemia due to chronic renal failure was found in 13.2% of patients [13].

Although there is a paradoxical feedback in renal production of erythropoietin, since the levels of this hormone actually increase over time, it has also been reported that the erythroid marrow may become less sensitive to erythropoietin stimulation, a key factor contributing along with possible nutritional deficits and comorbidities to the development of anaemia in the elderly [15]. Even distinguishing anemia of chronic inflammation from anemia of chronic kidney disease is somewhat challenging considering the fact that increased inflammation is seen in older adults even without chronic kidney disease and there are coexisting morbidities in this age group [12].

In our study, the most common anemia was found to be ACD, followed by IDA followed by anemia of blood loss. Elejalde Guerra et al. revealed that IDA is the most frequent followed by hemorrhagic anemia and ACD [16]. Our study does not tally with the findings of this study.

In our study, 30% had IDA, 3% had B12 deficiency and 2% had folate deficiency. Jack and co-workers revealed that 16.6% of the patients had only iron deficiency, 6.4% had folate deficiency only and 5.9% of the patients had B12 deficiency [13]. Hence our study corroborates with the findings of this study, iron deficiency being the most common of the nutrient deficiency anemias.

While studies suggest that vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency is the cause of anemia in 5–10% of elderly patients, the actual prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency is likely to be much higher [17]. Vitamin B12 deficiency is difficult to detect in the elderly. First, the symptoms and signs of vitamin B12 deficiency are not reliably present in the elderly. Only about 60% of such patients are anaemic. In addition, neurologic symptoms of B12 deficiency can develop before the patient becomes anemic [18]. Second, although this anemia is usually macrocytic and megaloblastic, it can be normocytic or even microcytic. Third, serum B12 levels do not reliably reflect tissue B12 deficiency. Up to 30% of patients with low-normal serum vitamin B12 levels have anemia and neurological disease [19].

Like vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency classically causes macrocytic anemia, although a significant proportion (25%) of elderly patients with folate deficiency have normocytic anemia [20]. The symptoms of folate deficiency are nearly indistinguishable from those of vitamin B12 deficiency.

In our study, in patients with IDA, an upper GI lesion was found in 78.6% of the patients and a colonic lesion was found in 29.4% of the patients. A GI malignancy was detected in 6.66% of the patients (3 duodenal, 1 gastric, 1 esophageal and 1 colonic) which is in agreement with various studies and reinforces the need for gastrointestinal tract evaluation as although some cases of iron deficiency do result from diet [21], blood loss through gastrointestinal lesions including malignancies contribute significantly in older adults [22, 23].

In our study, colonic malignancy was found in 3.35% of the patients with IDA. Rockey and Cello found that 16% with IDA had underlying colon cancer or premalignant polyps [24]. Hence our study corroborates with this study where an underlying colonic lesion was found in a significant percentage of patients who had iron deficiency.

The diagnosis of iron deficiency in the absence of any history of hemorrhage or unexplained anemias should be taken as evidence of occult gastrointestinal bleeding, and gastrointestinal tract evaluation should be performed [25].

2% of the patients were in the pancytopenic group. None of the patients had a preexisting disease and both of them were diagnosed with an underlying hematological malignancy.

In our study, only 2% of patients had no obvious underlying cause. In our study 1% cases had MDS. Beghe et al. showed that 14–50% of anemic elderly had no obvious underlying cause [26]. Jack and co-workers revealed 33.6% of the patients in his study group had unexplained anemia [13].

Other study groups have reported that it is likely that some proportion of unexplained anemia cases are caused by myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), another common hematologic condition in older adults [27].

Our study hence highlights the fact that most of the anemic elderly have an underlying treatable cause for anemia. It is essential therefore that the treating physician is aware of the coexistence of anemia in elderly, although the presenting manifestation may be for a different reason. It becomes, therefore, all the more pertinent to look for severity and type of anemia, possible etiologies and appropriate correction. As normocytic anemia is the most common blood smear diagnosis, it is important to bear in mind that normocytic blood picture in an anemic elderly should not be disregarded.

Appropriate attention should also be paid towards diet and nutrition of the geriatric population. It is advisable to evaluate each anaemic patient carefully, irrespective of the screening costs, provided that the diagnostic tests chosen are appropriate, reasonable and justified. Given the association of anaemia with poorer quality of life, comprehensive geriatric assessment essentially should include clinical review for presence of anemia and associated signs to reflect the possible etiology.

Conclusion

Failure to evaluate anemia in elderly could lead to delayed diagnosis of potentially treatable conditions. Non specific symptoms like fatigue and weakness should not be ignored in the geriatric population as they could be important pointers towards presence of anemia in these patients. An effort should always be made to reach etiological diagnosis before instituting specific therapy.

References

- 1.Ania Lafuente BJ, Fernandez-Burriel Tercero M, Suarez Almenara JL, Betancort Mastrangelo CC, Guerra Hernandez L. Anemia and functional capacity at admission in a geriatric home. An Med Interna. 2001;18(1):9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salive ME, Cornoni-Huntley J, Guralnik JM, et al. Anemia and hemoglobin levels in older persons: relationship with age, gender, and health status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:489–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ania BJ, Suman VJ, Fairbanks VF. Incidence of anemia in older people: an epidemiologic study in a well defined population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:825–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb01509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Onder G, Ferrucci L, Wallace RB, Pahor M. Anemia and decline in physical performance among older persons. Am J Med. 2003;115:104–110. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Definition of an older or elderly person. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/index.html. Retrieved August 29, 2010

- 6.Mary Lynn R, Sutin D (2003) Blood disorders and their management in old age. In: Geriatric medicine and gerontology. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburg, pp 1229–1230

- 7.Davenport J. Macrocytic anemia. Am Fam Physician. 1996;53(1):155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varat M, Adolph R, Fowler N. Cardiovascular effects of anemia. Am Heart J. 1972;83:415–426. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(72)90445-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta BC. Iron deficiency anemia. In: Shah S, Anand M, editors. API textbook of medicine. 6. Mumbai: Association of Physicians of India; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joosten E, Pelemans W, Hiele M. Prevalence and causes of anemia in a geriatric hospitalized population. Gerontology. 1992;38:111–117. doi: 10.1159/000213315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elis A, Ravid M, Manor Y, Bental T, Lishner M. A clinical approach to idiopathic normocytic–normochromic anemia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:832–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milman N, Schultz-Larsen K. Iron stores in 70 year old Danish men and women. Ageing. 1994;6(2):97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF03324223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaves PHM, Ashar B, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Looking at relationship between hemoglobin concentration and prevalent mobility difficulty in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(7):1257–1264. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Metz JA. High prevalence of biochemical evidence of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency does not translate into a comparable prevalence of anemia. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 Suppl):S74–S85. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller CR, Odden MC, Fried LF, Newman AB, Angleman S, Green CA, et al. Kidney function and markers of inflammation in elderly persons without chronic kidney disease: the health, aging, and body composition study. Kidney Int. 2007;71:239–244. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elejalde Guerra JI, Alonso Martinez JL, Rubio Vela T, Garcia Labairu C, Llorente B, Echegaray M. Etiological study and diagnosis of anemia in adults over 60 years of age. Sangre. 1999;44(6):418–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumner AE, Chin MM, Abraham JL, Berry GT, Gracely EJ, Allen RH, et al. Elevated methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine levels show high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency surgery. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:469–476. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernetsky A, Sofer O, Rafael C, Ben-Israel J (2002). Prevalence and etiology of anemia in an institutionalized geriatric population. Harefuah 141(7):591–594, 667 [PubMed]

- 19.Stabler SP. Vitamin B12 deficiency in older people: improving diagnosis and preventing disability [Editorial] J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1317–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seward SJ, Safran C, Marton KI, Robinson SH. Does the mean corpuscular volume help physicians evaluate hospitalized patients with anemia? J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:187–191. doi: 10.1007/BF02600530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coban E, Timuragaoglu A, Meric M. Iron deficiency anemia in the elderly: prevalence and endoscopic evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract in outpatients. Acta Haematol. 2003;110:25–28. doi: 10.1159/000072410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockey DC, Cello JP. Evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract in patients with iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1691–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joosten E, Ghesquiere B, Linthoudt H, Krekelberghs F, Dejaeger E, Boonen S, et al. Upper and lower gastrointestinal evaluation of elderly inpatients who are iron deficient. Am J Med. 1999;107:24–29. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00162-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockey DC, Cello JP. Evaluation of gastrointestinal tract in patients with iron deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;329:1691–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carmel R. Anemia and aging: an overview of clinical, diagnostic and biological issues. Blood Rev. 2001;15:9–18. doi: 10.1054/blre.2001.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beghe C, Wilson A, Ershler WB. Prevalence and outcome of anemia in geriatrics: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(7):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drewnowski A, Shultz JM. Impact of aging on eating behaviors, food choices, nutrition, and health status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2001;5:75–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]