Abstract

Mycoplasma pneumonia (M. pneumonia) is usually not considered among the several pathogens that induce immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). We report a child with a clinical diagnosis of severe ITP that was associated with M. pneumonia pneumonia, and review the few cases described in the English literature. We suggest that thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection may constitute a subset of ITP, although unlike ITP it occurs concomitantly with the infection and tends to be more severe than “classic” ITP. We recommend that prompt specific antibiotic and immune modulating treatment should be initiated in appropriate clinical settings.

Keywords: Immune, Mycoplasma, Pneumonia, Thrombocytopenia

Introduction

Thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection is rare, and usually has a severe course. We report a child presenting with severe thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia pneumonia. We also review the few cases of Mycoplasma associated thrombocytopenia in the English literature between 1966 and 2008.

Thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection appears in two clinical settings—as a part of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The etiology, clinical course and outcome of thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection that is not a part of TTP or DIC are unknown.

We reviewed the seven cases of thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection appearing in the English literature. We evaluated the diagnostic workup in each case and described the clinical course and its resemblances to ITP.

Case Report

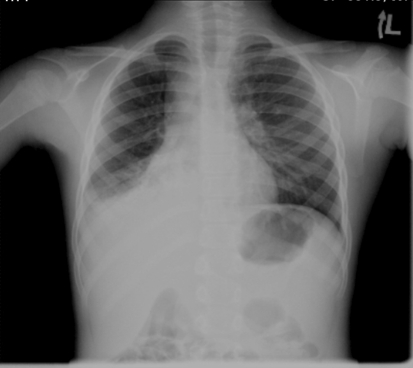

A 7-year-old girl was admitted to the pediatric department with 1 day history of fever and petechiae over both legs. A week prior to the admission she had fever for 1 week and a maculopapular rash on her face, a viral infection was assumed and she did not get any treatment. At the age of 6 months a vascular ring was resected; as a result, her left vocal cord and left diaphragm were paralyzed. Since then she had several admissions for asthmatic attacks, acute laryngitis and pneumonia. Platelets counts on previous admissions were at the range of 240–480 × 103/μl. On admission she appeared well, speaking in a hoarse voice. Her temperature was 38.2°C, pulse rate 112/min, respiratory rate 21/min, blood pressure 112/60 and O2 saturation 96% on ambient air. She had purpura and petechiae on her legs, buttocks, arms and face. Some petechiae were seen on the hard palate, oral mucous membranes and lips. Crepitations were heard over both lungs’ lower fields; the rest of her physical examination was unremarkable. Complete blood count revealed WBC of 22.3 × 103/μl (Neutrophiles 16 × 103/μl, Lymphocytes 5.2 × 103/μl, Monocytes 3.8 × 103/μl, and Eosinophiles 0.2 × 103/μl), Hemoglobin of 11.1 g/dl and platelet count of 2 × 103/μl. Red cells appeared normal on blood film with no features of microangiopathy. CRP was 73.8 mg/l. Liver and renal functions, PT and PTT coagulation studies, and D-dimer were within normal limits. A chest X-ray demonstrated right middle lobe infiltrate (Fig. 1). Presumptive diagnoses of ITP and RML pneumonia were made and treatment was initiated with one dose of IVIG 0.8 g/kg and daily IV Ceftriaxone at 50 mg/kg. Twelve hours after the IVIG administration, platelet count was 1.2 × 103/μl. Bone marrow examination revealed normal cellularity with young megakaryocytes, compatible with the diagnosis of ITP. Thereafter severe hemoptysis (>8 ml/kg) developed and the patient was admitted to the PICU. As there was no response to IVIG at 12 h and the patient was actively bleeding, Methylprednisolone 4 mg/kg for 4 days was started [1] and 4 units of platelets were administered. A Medline search for ITP and pneumonia retrieved 4 case reports of ITP that presented with M. pneumonia, and clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day was added to the treatment regimen. A second dose of IVIG was given 24 h after the first dose. Hemoptysis resolved after another day (day 3 of admission), when the platelet count started to increase gradually, and then dropped after the cessation of steroids on day 5. A second course of steroids at the same dose was begun on day 8 and tapered gradually over 21 days, while the platelet count steadily increased, exceeding 150 × 103/μl at 4 weeks from presentation. A positive Mycoplasma IgM titer at diagnosis and a 1:160 titer at 2 months confirmed the clinical diagnosis. Sputum culture was not informative for technical reason and bronchoalveolar lavage was considered too risky at the time of active bleeding. Serology for a panel of viruses associated with ITP (EBV, CMV, hepatitis, HIV and parvovirus) was negative for acute infection. Anti-nuclear factor and dsDNA were negative. Serology for anticardiolipin and APLA was negative. The child is 20 months after the event with normal CBC.

Fig. 1.

AP chest X-ray demonstrating right lower lobe infiltrate

Literature Review

A Medline literature search conducted using the key words “immune”, “thrombocytopenia”, “purpura”, “pneumonia” and “Mycoplasma” revealed only one case report describing the association of ITP and pneumonia. Thirteen more cases were identified through cross-references; four of these cases were diagnosed as TTP and excluded from this review. Three cases were mentioned in a report of 83 patients with M. pneumonia infection, but lack details on the clinical presentation, platelet counts and outcome of the clinical course [2]. The details of the remaining 7 cases and our case of thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection with no features of TTP or DIC are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and clinical picture of patients with thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection [3–9]

| Case | Source | Age (Year) Sex |

Presentation | Lowest Plts [× 103/µl] Time (days) |

Later complications | Evidence for mycoplasma | Treatment | Time to anti-mycoplasma treatment (days) | Time to Plts > 150 [× 103/µl] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Current case 1 | 7 Female |

Fever, cough, pneumonia, petechiae and purpura | 1.2 1 |

Hemoptysis | IgM + total anti-mycoplasma 1:64 | IVIG, prednisolone, clarythromycin | 1 | 2 months |

| 2 | Tsai et al. [9]. | 0.7 Female |

Cough, shortness of breath and fever, pneumonia, petechiae | 14 admission |

None | CFT 1:4; cold agglutinin 1:128 | Prednisolone, minocycline | On admission | 14 days |

| 3 | Miller et al. [3]. | 44 Male |

Fever, cough, pneumonia, hematuria, behavioral changes | 7 admission |

Apnea, brain stem hemorrhage, obstructive hydrocephalus; death on day 14 | CFT 1:4 to 1:32; cold agglutinin 1:128 | Erythromycin, cefotaxime, amikacin, methylprednisole | On admission | Never |

| 4 | Veenhoven et al. [6]. | 17 Male |

Headache, 12 days fever, cough, dyspnea, pneumonia, petechiae | 25 admission |

None | CFT 1:64; IgM + cold agglutinin 32–256 | Prednisolone, erythromycin | On admission | 3 months |

| 5 | Beattie [4] | 4 Male |

Cough, fever, pneumonia | 4 1 |

Purpura, epistaxis, hematuria | IgM 80–320 | IVIG | Not specified | 42 × 103/µl on day 5 |

| 6 | Pugliese et al. [8]. | 7 Male |

Spiking fevers, shaking chills, muscle weakness, sinusitis | <18 1 |

Headache, vomiting, diarrhea | ELISA 1.01; cold agglutinin 1:64 | Ceftriaxone switched to erythromycin, prednisone | Between days 2–4 | 14 days |

| 7 | Isoyama et al. [5]. | 8 Male |

Rhinorrhea, cough, epistaxis, petechiae and hematoma on skin and mucous membranes | 2 admission |

Epistaxis, bloody stool, hematuria | ELISA 4 to >1.5; 3 positive cultures | Prednisone; IVIG | On admission | 14 days |

| 8 | Venkatesan et al. [7]. | 21 Male |

Cough, fever, pneumonia, purpuric rash, bleeding gums, hemoptysis, macroscopic hematuria, bloody stools | 1 1 |

Intracranial haemorrhage; death on day 2 | CFT 1:8000; total anti-mycoplasma 1:5120 | Cefotaxim, methylprednisolon erythromycin | 1 | Never |

Clinical Features

There were six males and two females of ages 7 months to 44 years, five patients were younger than 8 years. Six patients presented with fever, cough and pneumonia, one with sinusitis, one with rhinorrhea and cough and one with fever and arthralgia. Bleeding manifestations were noted in 6 patients on presentation including petechiae (five patients), purpura (two patients), macroscopic hematuria (two patients) and epistaxis and bloody stool each in one patient. One child developed purpura, epistaxis and hematuria 24 h after he had initially presented with pneumonia, and one child had no bleeding manifestations. Platelet counts on presentation ranged from 2 to 66 × 103/μl. In five patients platelet count dropped to 1–18 × 103/μl on day 1. Bone marrow aspiration was performed on six patients: three had an increased number of megakaryocytes, two had normal cellularity and one had a decreased number of megakaryocytes.

Testing for Mycoplasma

There was no uniformity with respect to the proof of Mycoplasma infection. A four-fold increase in complement fixation test (CFT) for Mycoplasma titer and Mycoplasma-specific IgM by ELISA were demonstrated in one [3] and two [4, 5] patients, respectively. Other tests that supported the diagnosis of Mycoplasma were high titers for CFT and cold agglutinins in three patients [6–8], specific antibodies in three patients (index case) [8] and decreasing titers of hemagglutination in one case [9].

Three of the authors who looked for specific anti-platelet antibodies were unable to demonstrate them [5, 7, 8]. Two of the three, however, did find platelet-associated IgG by immunofluorescence test [5, 7].

Treatment and Outcome

All patients were treated with steroids, IVIG or both. Seven of the eight patients received specific anti-Mycoplasma antibiotics with a delay of 2–4 days in introducing this treatment in one patient. In six patients the platelet counts recovered to normal values by day 14–90 (mean 38.4, median 81 days). Last reported count on one child was 42 × 103/μl on day 5. Two patients died on day 2 and 14, of intracranial and brain stem hemorrhages, respectively.

Discussion

In this article we describe a patient with severe thrombocytopenia associated with an infection caused by M. pneumonia. We reviewed the literature and were able to identify only 7 cases with thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection that was not related to TTP or DIC. Thrombocytopenia induced by Mycoplasma is rarely reported. The comprehensive review on M. pneumonia by Waites and Talkington [10] mentioned TTP, but not thrombocytopenia unrelated to TTP as a known rare complication. Neither is M. pneumonia mentioned as a cause of ITP in a relatively large series of ITP patients [11]. It is common knowledge that ITP is triggered by viral infection that precedes the clinical picture of ITP by a few days to a few weeks [12]. However, such an association has been described in only small series and for few specific viruses [13–18]. It is possible that M. pneumonia infection accounts for more cases of ITP and the rate of this association is underestimated due to lack of awareness of this connection.

The clinical picture of thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection resembles that of ITP in some aspects. Like ITP, it tends to appears at a young age with mean and median ages of 13.7 and 8 years, respectively. The clinical course, which is considerably different in each patient, ranging from mild to fatal, also resembles the course diversity seen in ITP.

However, several features of the 8 cases described distinguish them from “classic” ITP. First, thrombocytopenia occurred concomitantly with the infection as opposed to an interval of days to weeks between infection and “classic” ITP [19]. Secondly, 4 of 8 patients experienced severe course with severe bleeding including 2 with fatal intracranial hemorrhage in contrast to around 3% severe bleeding and less than 0.6% fatality in “classic” ITP [19]. Thirdly, three of the authors who looked for specific anti-platelet antibodies were unable to demonstrate them, whereas such antibodies are found in many patients with ITP. This subset of ITP could be considered as secondary caused by “miscellaneous systemic infection” that accounts for 2% of all ITP cases [20].

Several mechanisms are suggested to explain these differences. It could be that the presence of the infecting agent itself has a role in the pathogenesis of Mycoplasma induced ITP, through direct connection to the platelet and destroying it. It could also be that the kinetics of the immune response is different in the case of Mycoplasma.

The etiology of the thrombocytopenia associated with M. pneumonia infection seems to be autoimmune, resembling that of ITP [21]. Several mechanisms for the destruction of platelets have been suggested. M. pneumonia could induce the production of anti-platelet antibodies. However, anti-platelet antibodies have not been detected in the three cases where they were checked [5, 7, 8], compared to 15% of ITP patients who lacked anti platelet antibodies [22]. An increased titer of platelets associated IgG was found in two cases where it was looked for [4, 5], but the antibodies produced in response to M. pneumonia at the time of acute infection are IgM type. It could still be that the antibodies bind non-specifically to the platelet surface leading to their clearance. Biberfeld and Norberg [23] have demonstrated the development of immune complexes during M. pneumonia infection. These complexes may cause platelet aggregation and release of serotonin [24], and might enhance clearance of platelets. Molecular mimicry was suggested as a mechanism for platelet binding in ITP [25] and can also take place with Mycoplasma. Indeed, Wagner et al. [26] have demonstrated ether lipids of M. fermentans that are structurally similar to the platelet activating factor which stimulates platelet aggregation, suggesting molecular mimicry for the thrombocytopenia induced by Mycoplasma infections. Finally, direct binding of Mycoplasma to the platelets, generating a complex that is then recognized as foreign by the immune system, might be another option. Whatever the mechanism would be, a special behavior of a subset of ITP caused by a certain organism is an intriguing option, as was suggested recently for ITP triggered by CMV infection [27].

This literature review should increase the awareness of clinicians to the association between thrombocytopenia and Mycoplasma infection, suggesting testing for Mycoplasma in appropriate clinical settings. Unlike “classic” ITP, the concomitant occurrence of thrombocytopenia and Mycoplasma infection suggest an important role for early initiation of specific anti-Mycoplasma therapy to rapidly eliminate the causative agent. This, in turn, might enhance recovery of the platelet count and decrease the rate of complications. Initiation of early immune modulating treatment with steroids and/or immunoglobulins might further contribute to rapid recovery.

References

- 1.Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, Michel M, Provan D, Arnold DM, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Chong BH, Cooper N, Godeau B, Lechner K, Mazzucconi MG, McMillan R, Sanz MA, Imbach P, Blanchette V, Kuhne T, Ruggeri M, George JN. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113:2386–2393. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-162503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hers JF, Masurel N. Infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae in civilians in the Netherlands. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1967;143:447–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1967.tb27689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller SN, Ringler RP, Lipshutz MD (1986) Thrombocytopenia and fatal intracerebral hemorrhage associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. NY State J Med 86:605–607 [PubMed]

- 4.Beattie RM. Mycoplasma and thrombocytopenia. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:250. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.2.250-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isoyama K, Yamada K. Previous Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection causing severe thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 1994;47:252–253. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830470329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veenhoven WA, Smithuis RH, Kerst AJ. Thrombocytopenia associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Neth J Med. 1990;37:75–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venkatesan P, Patel V, Collingham KE, Ellis CJ. Fatal thrombocytopenia associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Infect. 1996;33:115–117. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(96)93043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pugliese A, Levchuck S, Cunha BA (1993) Mycoplasma pneumoniae induced thrombocytopenia. Heart Lung 22:373–375 [PubMed]

- 9.Tsai YM, Lee PP, Liu CH (1985) A case of primary atypical pneumonia complicated with severe thrombocytopenia. Taiwan Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi 84:742–746 [PubMed]

- 10.Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:697–728. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.697-728.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn J. Thrombocytopenia in childhood: an evaluation of 433 patients. Scand J Haematol. 1976;16:226–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1976.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rand ML, Wright JF. Virus-associated idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfus Sci. 1998;19:253–259. doi: 10.1016/S0955-3886(98)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feusner JH, Slichter SJ, Harker LA. Mechanisms of thrombocytopenia in varicella. Am J Hematol. 1979;7:255–264. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830070308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman LA, Wolff SM. Acute thrombocytopenic purpura in infectious mononucleosis. JAMA. 1959;171:2208–2210. doi: 10.1001/jama.1959.73010340001013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho-Yen DO, Hardie R, Sommerville RG. Varicella-induced thrombocytopenia. J Infect. 1984;8:274–276. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(84)94147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitamura K, Ohta H, Ihara T, Kamiya H, Ochiai H, Yamanishi K, Tanaka K. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura after human herpesvirus 6 infection. Lancet. 1994;344:830. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morse EE, Zinkham WH, Jackson DP. Thrombocytopenic purpura following rubella infection in children and adults. Arch Intern Med. 1966;117:573–579. doi: 10.1001/archinte.117.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terada H, Baldini M, Ebbe S, Madoff MA. Interaction of influenza virus with blood platelets. Blood. 1966;28:213–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George JN, Woolf SH, Raskob GE, Wasser JS, Aledort LM, Ballem PJ, Blanchette VS, Bussel JB, Cines DB, Kelton JG, Lichtin AE, McMillan R, Okerbloom JA, Regan DH, Warrier I. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a practice guideline developed by explicit methods for the American Society of Hematology. Blood. 1996;88:3–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cines DB, Bussel JB, Liebman HA, Luning Prak ET. The ITP syndrome: pathogenic and clinical diversity. Blood. 2009;113:6511–6521. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-129155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medeiros D, Buchanan GR. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: beyond consensus. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:4–9. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomer A. Autoimmune thrombocytopenia: determination of platelet-specific autoantibodies by flow cytometry. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47:697–700. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biberfeld G, Norberg R. Circulating immune complexes in Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Immunol. 1974;112:413–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfueller SL, Luscher EF. The effects of immune complexes on blood platelets and their relationship to complement activation. Immunochemistry. 1972;9:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(72)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oldstone MB. Molecular mimicry and immune-mediated diseases. FASEB J. 1998;12:1255–1265. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner F, Rottem S, Held HD, Uhlig S, Zahringer U. Ether lipids in the cell membrane of Mycoplasma fermentans. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6276–6286. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiMaggio D, Anderson A, Bussel JB. Cytomegalovirus can make immune thrombocytopenic purpura refractory. Br J Haematol. 2009;146:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]