Abstract

Dopaminergic (DA) agonist-induced yawning in rats seems to be mediated by DA D3 receptors, and low doses of several DA agonists decrease locomotor activity, an effect attributed to presynaptic D2 receptors. Effects of several DA agonists on yawning and locomotor activity were examined in rats and mice. Yawning was reliably produced in rats, and by the cholinergic agonist, physostigmine, in both the species. However, DA agonists were ineffective in producing yawning in Swiss–Webster or DA D2R and DA D3R knockout or wild-type mice. The drugs significantly decreased locomotor activity in rats at one or two low doses, with activity returning to control levels at higher doses. In mice, the drugs decreased locomotion across a 1000–10 000-fold range of doses, with activity at control levels (U-91356A) or above control levels [(±)-7-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin HBr, quinpirole] at the highest doses. Low doses of agonists decreased locomotion in all mice except the DA D2R knockout mice, but were not antagonized by DA D2R or D3R antagonists (L-741 626, BP 897, or PG01037). Yawning does not provide a selective in-vivo indicator of DA D3R agonist activity in mice. Decreases in mouse locomotor activity by the DA agonists seem to be mediated by D2 DA receptors.

Keywords: BP 897, dopamine agonist, dopamine D2/D3 receptor, knockout mouse, L-741626, PD 128907, PG01037, 7-OH-DPAT, quinpirole, U-91356A

Introduction

The dopaminergic (DA) D3R is classified as a member of the D2-like family of dopamine receptors based on its close sequence homology to the DA D2R (Sokoloff et al., 1990). The relatively restricted localization of the DA D3R in mesolimbic brain areas has contributed to the interest in this receptor, and it has been suggested as a therapeutic target for various psychiatric disorders (see reviews by Joyce and Millan, 2005; Newman et al., 2005).

Despite a considerable amount of research on the DA D3R, an understanding of the receptor and the pharmacology of its ligands, particularly in vivo, remains incomplete (Levant, 1997; Xu et al, 1999). Moreover, the relative selectivity of various putative D3R ligands can vary substantially from one study to the next, and depend on features of the assays, including especially the radiolabel used (Levant, 1997).

In addition to the paucity of selective agonist and antagonist ligands, studies of the in-vivo pharmacology of putative DA D3R ligands have been hindered by a lack of functional assays that are uniquely and selectively responsive to actions at DA D3 receptors. Several in-vivo effects have been suggested as functional consequences of DA D3R activity. Reports of studies conducted, in rats show biphasic dose-effect curves with decreases in locomotor activity at low doses yielding to stimulation of activity at higher doses. Several investigators have suggested that the decreases obtained at low doses of DA agonists are because of actions at presynaptic DA receptors, whereas others have suggested that the decreases in activity were because of actions at the DA D3R (Daly and Waddington, 1993; Gilbert and Cooper, 1995; Pugsley et al., 1995; Bristow et al., 1996; Depoortere et al., 1996; Maj et al., 1999; Rogóz and Skuza, 2001). Most of the earlier reports on the effects of DA agonists on locomotor activity in mice indicate only dose-related decreases (Pugsley et al., 1995; Geter-Douglass et al., 1997; Tirelli et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1999; Boulay et al., 1999a, 1999b; Pritchard et al., 2003).

Yawning in rodents has long been associated with DA activity (e.g. Mogilnicka and Klimek, 1977; Holmgren and Urbá-Holmgren, 1980; Yamada and Furukawa, 1980). As noted by Collins et al. (2005), early hypotheses attributed yawning to various DA mechanisms, and more recently the biphasic dose-effect curve has been suggested to be because of a DA D3R mediated stimulation of yawning, accompanied by a DA D2R inhibition of the effect. Drugs with preferential activity at the DA D3R should produce a biphasic dose-effect curve (Kostrzewa and Brus, 1991; Levant, 1997). Indeed, studies of several DA agonists, including; PD 128907 ((S)-(+)-(4aR, 10bR)-3,4,4a, 10b-tetrahydro-4-propyl-2H,5H-[1]benzopyrano-[4,3-b]-1,4-oxa zin-9-ol HCl), quinelorane, and (±)-7-hydroxy-2-dipropy-laminotetralin HBr (7-OH-DPAT) produced significant, dose-dependent increases in yawning with maximum stimulation at an intermediate dose, and decreases from this maximum at the highest doses. Several antagonists with reported selectivity for the DA D3R, including U-99,194A, SB 277011A, PG01037, and less so nafadotride, shifted the ascending limb of the biphasic dose-effect curve rightward, without the effects on the descending limb. In contrast, the nonselective antagonists, haloperidol, and raclopride, shifted the entire biphasic dose-effect curve rightward, whereas the DA D2R preferring antagonist, L-741626, selectively shifted the descending limb of the biphasic dose-effect curve (Collins et al., 2005; Sevak et al., 2007).

These studies were initiated to further explore the respective roles of dopamine receptor subtypes in the yawning induced by DA D3R preferring agonists. It was hypothesized that the biphasic dose-effect curve for the agonists would be absent, or substantially modified, in mice with a genetic deletion (knockout) of the DA D2 receptor (DA D2R KO) compared with wild-type (DA D2R WT) mice. In the initial stages of the study it was determined that, in contrast to what was obtained in rats, yawning was not produced by DA D3R preferring agonists in mice, including 7-OH-DPAT, PD 128907, quinpirole, quinelorane, and the nonselective agonist, apomorphine. However, casual observations indicated that several of the DA D3R preferring agonists decreased locomotor activity which was then studied fully to ensure that the absence of yawning was not because of the lack of sufficient dosage. The decreases in activity became of interest because they were reversed at higher doses with several agonists, and because they occurred over a profound range of doses. The range of doses was much greater than that for the decreases in activity in rats, and indeed much greater than the range of doses over which most behaviorally active drugs have their effects. In this study, we focused on the decrease in activity using pharmacological tools and mutant mouse lines to characterize its mechanism.

Methods

Subjects

Sprague–Dawley rats (Taconic Farms, Germantown, New York, USA) and Swiss–Webster (Taconic Farms or Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA), C3H (Harlan Laboratories), DA D2R KO, and WT mice (Kelly et al., 1997), and DA D3R KO and WT mice (Xu et al., 1997) served as subjects. The mutant mice used in these studies were the product of at least 10 generations of mating heterozygote mice with C57BL/6J mice. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled and humidity-controlled vivarium with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on 07:00h). All the experiments were conducted during the light phase of the light/dark cycle. Subjects were allowed to habituate to the colony room for at least 1 week before their use in these experiments. Food and water were available at all times except during the experimental tests. Experiments were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols.

Apparatus

Locomotor and yawning behaviors were tested in 40 × 40 × 40 cm clear acrylic chambers. The acrylic chambers were placed inside monitors (Accuscan Instruments, Inc., Columbus, Ohio, USA), which were equipped with light-sensitive detectors spaced 2.5 cm apart along two perpendicular walls. Mounted on the opposing walls were infrared light sources that were directed at the detectors. One count of horizontal activity was registered each time the subject interrupted a single beam. The locomotion and yawning behaviors of rats were recorded in the whole chambers, whereas locomotion and yawning behaviors in pairs of mice were monitored with each in a separate diagonal quarter of the acrylic chamber, which was partitioned into quadrants.

Procedures

Subjects were habituated to the acrylic chamber for at least 60 min before tests. For drug interaction studies, there was a saline or L-741626 injection at 30 min into the habituation period (30-min pretreatment before a second injection and behavioral assessments). Locomotor activity was recorded automatically whereas yawning was recorded by visual observation each for 60 min immediately after the habituation period. An instance of yawning was recorded when the animal opened its mouth widely and gradually, maintained the opened position for at least 1 s, and then closed the mouth rapidly. As this behavior is easily defined and unique in its topographic presentation, measurements of yawning frequency were taken by trained observers (S-M.L, G.T.C.), who were not blind to treatments. In unpublished experiments from this laboratory in which two blind independent observers were employed, the reported frequencies of yawning were highly correlated (r = 0.94) with a 95% confidence interval of 0.90–0.96 (P < 0.001). Further, these data in rats compare quite favorably to the results from other studies, indicating that measurement techniques with high reliability were implemented.

Rats and Swiss–Webster mice were generally tested once with the following exceptions. As the absence of an elicitation of yawning unfolded (data detailed in Table 1), several subjects were tested more than once, with at least 48 h between exposures to drugs. In studies of the effects of physostigmine, L-741626, PD 128907, and 7-OH-DPAT in DA D2R mutant mice, subjects were tested with either the full range (or 1–3 doses) of drug or vehicle, because of the limited supply of the animals, again with at least 48 h gap between exposures to drugs. Repeated testing in rats (twice each week) has been shown in pilot studies to have no effect on the frequency of yawning.

Table 1.

Drugs assessed and their dose ranges for induction of yawning in mice

| Drug | Mouse strain or line | Dose range (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 7-OH-DPAT | Swiss–Webster | 0.001–100 (n = 4, SC) |

| PD 128907 | Swiss–Webster and C3H | 0.01–100 (n = 6–8, SC or IP) |

| Quinpirole | Swiss–Webster | 0.003–100 (n = 6–8, SC or IP) |

| Quinelorane | Swiss–Webster and C3H | 0.032–0.32 (n = 8, SC) |

| Apomorphine | Swiss–Webster | 0.0003–0.03 (n = 8, SC) |

| U-91356A | Swiss–Webster | 0.01–100 (n = 6, IP) |

| Pramipexole | Swiss–Webster | 0.0003–0.01 (n = 8, IP) |

| 7-OH-DPAT | DA D2R WT | 0.03–0.3 (n = 4, SC) |

| PD 128907 | DA D2R WT | 0.001–1.0 (n = 4, SC) |

| Quinpirole | DA D2R WT | 0.001–0.1 (n = 6, SC) |

| U-91356A | DA D2R WT | 0.001–0.1 (n = 6, IP) |

| 7-OH-DPAT | DA D2R KO | 0.03–0.3 (n = 4, SC) |

| PD 128907 | DA D2R KO | 0.001–1.0 (n = 4, SC) |

| Quinpirole | DA D2R KO | 0.001–0.1 (n = 6, SC) |

| U-91356A | DA D2R KO | 0.001–0.1 (n =6, IP) |

| 7-OH-DPAT | DA D3R WT | 0.01–0.3 (n =6, SC) |

| PD 128907 | DA D3R WT | 0.03–0.3 (n = 6, SC) |

| Quinpirole | DA D3R WT | 0.01–1.0 (n = 6, SC) |

| U-91356A | DA D3R WT | 0.01–1.0 (n = 6, IP) |

| 7-OH-DPAT | DA D3R KO | 0.01–0.3 (n = 6, SC) |

| PD 128907 | DA D3R KO | 0.03–0.3 (n = 6, SC) |

| Quinpirole | DA D3R KO | 0.001–1.0 (n = 6, SC) |

| U-91356A | DA D3R KO | 0.01–1.0 (n = 6, IP) |

Each dose was examined in 4–8 animals. No clear yawning behavior was observed.

7-OH-DPAT, (±)-7-hydroxy-2-dipropylaminotetralin HBr; IP, intraperitoneal injection; KO, knockout; SC, subcutaneous injection; WT, wild-type.

Drugs

The drugs studied were 7-OH-DPAT hydrobromide, PD 128907 hydrochloride, quinpirole hydrochloride, physostigmine hemisulfate, U-91356A (R)-5,6-dihydro-5-(propylamino) 4H-imidazo[4.5.1-ij]quinolin-2-(1H)-one, mono hydrochloride), a DA D2R preferring agonist (Piercey et al., 1996), apomorphine hydrochloride, PG01037 (N-{4-[4-(2,3-dichlorophenyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-trans-but-2-enyl}-4-pyridine-2-yl-benzamide HC1, Grundt et al., 2005), BP 897, and L-741626. All subsequent designations refer to the respective salt forms except L-741626. The 7-OH-D PAT, PD 128907, quinpirole, and physostigmine were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). L-741626 and PG01037 were synthesized in the Medicinal Chemistry Section at NIDA Intramural Research Program, and the U-91356A was generously donated by Pharmacia and Upjohn (with attention to the request kindly provided by Dr Lisa Gold). L-741626 was dissolved in saline solution by adding drops of acetic acid solution. The pH was adjusted to 5–7 with NaOH solution. PG01037 was dissolved in water and BP 897 was dissolved in 20% β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich). Other drugs were dissolved in saline. 7-OH-DPAT solution was freshly made before injections. The drug solutions were administered by the intraperitoneal route (physostigmine, L-741626) or subcutaneously (apomorphine, 7-OH-DPAT, PD 128907, and quinpirole) at 1 ml/kg for rats or 1 ml/ 100 g for mice, with doses administered on the basis of body weight. In the initial studies of yawning behavior in mice (Table 1), 7-OH-DPAT, PD 128907, and quinpirole solutions were also administered by intraperitoneal injection because of the absence of yawning behavior after subcutaneous administration. Physostigmine, U-91356A, BP897, PG1037 were given through intraperitoneal injection according to earlier publications. Limited supplies of U-91356A precluded extending some of the studies.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. For the drug-alone tests, one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), or one-way ANOVA, as appropriate, was followed by a Dunnett’s post-hoc test. For studies of drug interaction on mutant mice, data were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA or a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA followed by a Fisher’s least significant difference post-hoc assessment of all pair-wise effects. The level of significance was P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Effects of DA D3R preferring agonists on yawning in rats and mice

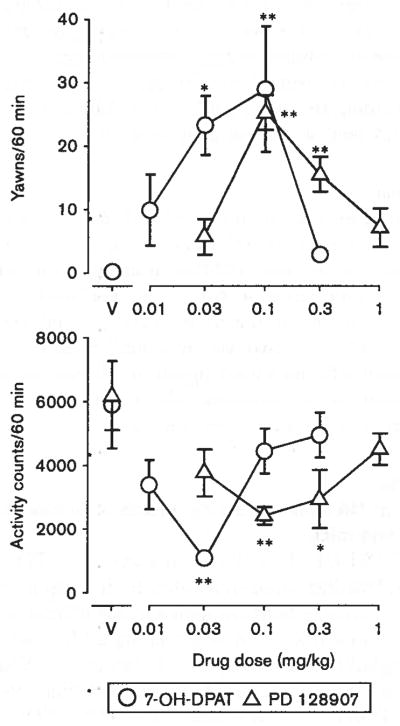

Both 7-OH-DPAT (0.01–0.3 mg/kg) and PD 128907 (0.03–1.0 mg/kg) dose-dependently increased the frequency of yawning behavior from virtually none after vehicle injection, to a maximum approaching 30 for each 60 min at 0.1 mg/kg for each drug (Fig. 1; top panel). Significant effects of treatment were obtained with both the drugs [7-OH-DPAT: F(4,15) = 5.22, p < 0.01; PD 128907: F(4,19) = 16.5, p < 0.01]. The dose-effect curves were biphasic, with dose-dependent increases up to the maximum obtained at 0.1 mg/kg, and less of an increase at higher doses.

Fig. 1.

Effects of 7-OH-DPAT and PD 128907 on yawning (top panel) and locomotor activity (bottom panel) in rats. Vertical axes: mean number of yawns in a 60-min observation period (top panel) or locomotor activity counts (bottom panel) during the same observation period. Horizontal axes: drug dose in mg/kg. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in four to six rats. Statistical significance of results versus vehicle controls according to a Dunnett’s test are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. V, vehicle.

In contrast to what was observed with rats, neither 7-OH-DPAT nor PD 128907 produced a significant increase in yawning behavior in Swiss–Webster mice (Table 1). The lack of effect was obtained over a relatively large range of doses that included those that produced maximal yawning in rats. The lack of effect with these two drugs prompted formal observational studies of several other DA agonists and different routes of administration. Despite the assessment at doses that earlier induced yawning with rats (Collins et al., 2005), yawning was not obtained at frequencies greater than that observed with vehicle (Table 1). These subsequent studies, and informal observations conducted during studies described below directed at locomotor activity with Swiss–Webster mice and DA D2R and DA D3R mutant mice, did not find yawning to be produced by any of the DA agonists tested.

Effects of physostigmine on yawning in rats and mice

As none of the DA agonists that produced yawning in rats were active in mice, we assessed the effects of the indirect cholinergic agonist, physostigmine that also induces yawning in rats. Physostigmine (0.1–0.4mg/kg) dose-dependently increased the incidence of yawning behavior in rats [F(3,12) = 18.6, P < 0.01, Table 2], with 0.2 mg/kg producing a significant difference from control (q = 7.06, P < 0.01). Physostigmine also produced significant effects in Swiss–Webster, DA D2R WT, and KO mice [F(3,12) = 16.1, P < 0.01; F(3,12) = 6.70, P < 0.01, and F(3,12) = 7.91, P < 0.01, respectively, Table 2], though the magnitude of these effects in the DA D2R WT and KO mice was much less than in the Swiss–Webster mice. There were no significant differences between the DA D2R WT and KO mice [F(1,18) = 0.04, NS].

Table 2.

Effects of physostigmine on yawning in mice and rats

| Treatment | Sprague–Dawley rat | Swiss–Webster mouse | DA D2R WT mouse | DA D2R KO mouse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 |

| Physostigmine 0.1 mg/kg | 3.75 ± 1.80 | 3.50 ± 1.32 | 5.00 ± 1.73a | 4.25 ± 0.479a |

| Physostigmine 0.2 mg/kg | 18.5 ± 2.60a | 18.0 ± 5.96a | 5.50 ± 0.646a | 5.00 ± 1.47a |

| Physostigmine 0.4 mg/kg | 6.50 ± 1.94 | 28.3 ± 2.32a | 2.50 ± 0.646 | 4.25 ± 0.479a |

Values represent the average number of yawns during a 60-min observation period. Each dose was examined in four animals.

KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

Significant outcome of Dunnett’s test (P < 0.01) versus vehicle group.

Effects of DA D3R-preferring agonists on locomotor activity in rats and mice

Both 7-OH-DPAT and PD 128907 also produced biphasic effects on locomotor activity in rats (Fig. 1, bottom panel). Significant treatment effects were obtained with both the drugs [7-OH-DPAT: F(4,15) = 4.88, P < 0.05; PD 128907: F(4,19) = 3.51, P < 0.05]. At 0.03 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT, there was a significant decrease in activity (q = 4.09, P < 0.01), with effects at higher (0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg) and lower (0.01 mg/kg) doses not significant. A significant decrease in locomotor activity was obtained with 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg of PD 128907 (q = 3.46, P < 0.01 and q = 2.85, P < 0.05, respectively), whereas the effects were not significantly different from control at higher (1.0 mg/kg) and lower (0.03 mg/kg) doses.

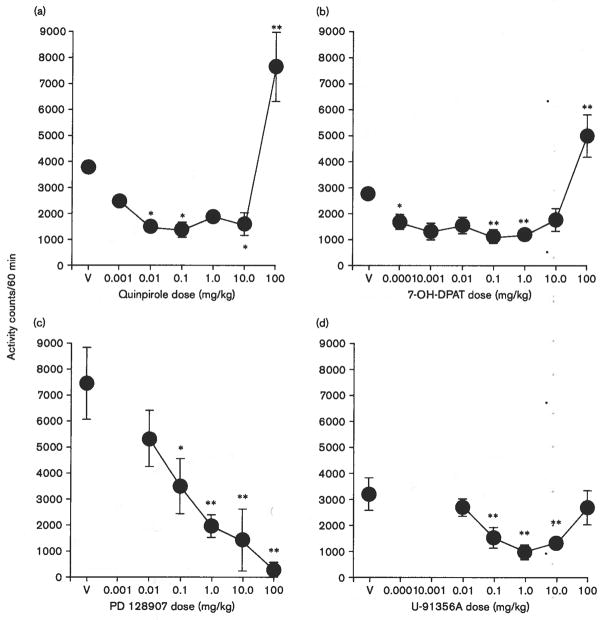

At low to intermediate doses, quinpirole (0.001 to 10.0 mg/kg) and 7-OH-DPAT (0.0001 to 1.0 mg/kg) decreased locomotor activity in Swiss–Webster mice (Fig. 2a and b). The decreases were not monotonic, with the highest dose (100 mg/kg) of each drug increasing activity above control levels. Decreases in activity were obtained over a remarkable 10 000-fold range of doses for quinpirole [F(6,35) = 16.5, P < 0.01] and 7-OH-DPAT [F(7,62) = 9.83, P < 0.01].

Fig. 2.

Effects of dopamine agonists on locomotor activity in Swiss–Webster mice. Ordinates: mean number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Horizontal axes: drug dose in mg/kg. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in four to 24 mice. Statistical significance of results versus vehicle controls according to a Dunnett’s test are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. V, vehicle, (a) Effects of quinpirole, (b) effects of 7-OH-DPAT, (c) effects of PD 128907, (d) effects of U-91356A.

The pattern of dose effects on locomotor activity with PD 128907 differed from 7-OH-DPAT and quinpirole (Fig. 2c), with only a dose-related monotonic decrease in locomotor activity evident [F(5,35) = 8.16, P < 0.01]. Doses of 0.1 mg/kg or greater significantly decreased activity, with lethality in all animals tested at 300 mg/kg of PD 128907. Baseline activity in these subjects was greater than that obtained with other drugs, which may have contributed to the absence of a return towards baseline levels at the high doses. Therefore, PD 128907 was studied again in new groups of subjects (data not shown). Vehicle levels of activity in these subjects averaged 3660 (± 636) counts/60-min, and were significantly decreased at doses from 3 to 100 mg/kg [one-way ANOVA F(4,40) = 5.77, P < 0.002].

The putative DA D2R receptor agonist, U-91356A, also decreased locomotor activity across an approximate 1000-fold range of doses (0.1–10 mg/kg). The dose-effect curve (Fig. 2d) resembled that for 7-OH-DPAT and quinpirole, though the highest dose only returned activity to control levels without exceeding them. Higher doses of the drug were not tested because of limits to the amount of drug available. The ANOVA for the effects of U-91356A indicated a significant effect of dose [F(5,48) = 4.74, P < 0.002].

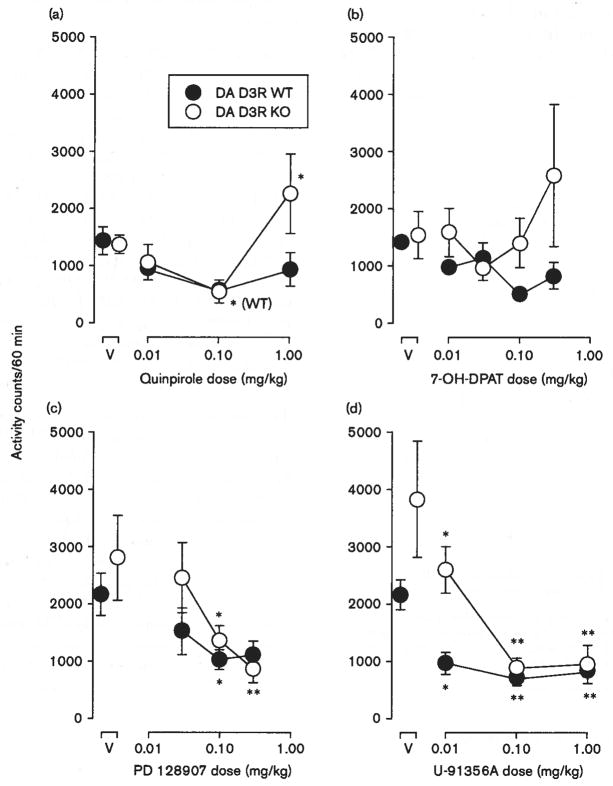

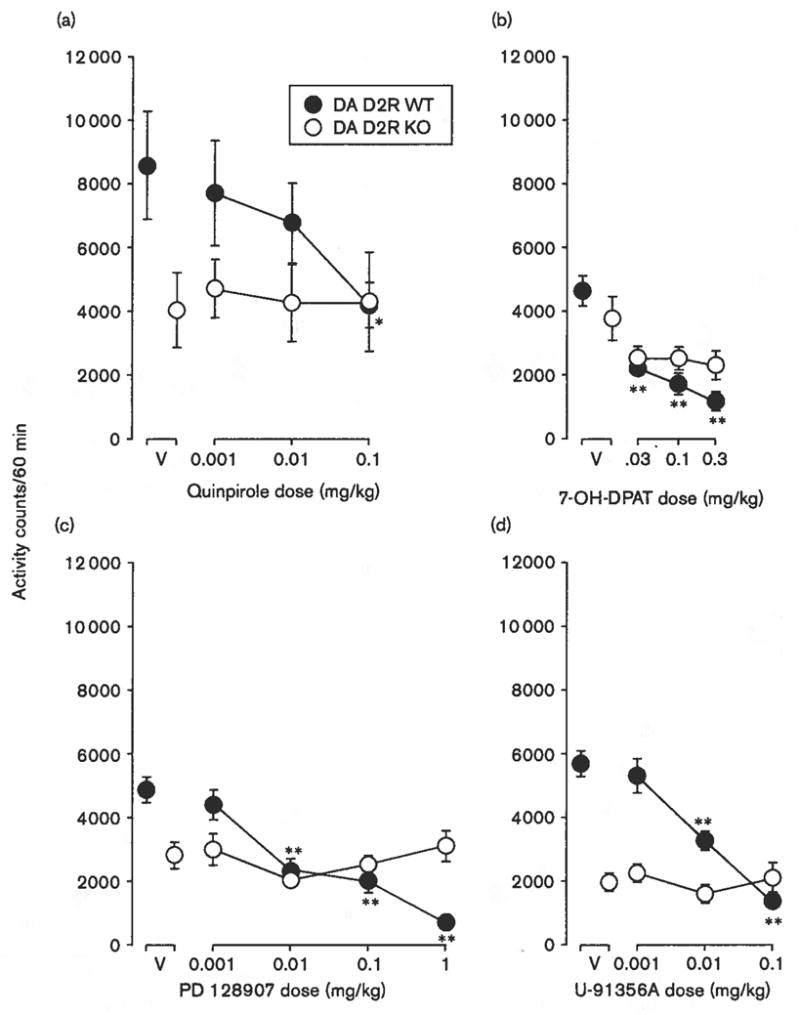

Mutant mice were studied to assess whether the decreases in activity produced by the low to intermediate doses of the agonists were because of effects mediated at the DA D2R or DA D3R. In general, locomotor activity levels were lower in the DA D2R KO compared with WT mice (compare open to filled points above V in Fig. 3). With quinpirole (Fig. 3a), a repeated-measures of ANOVA indicated a lack of overall significance of dose [F(3,30) = 2.36, P = 0.092] and genotype [F(1,30) = 2.66, NS]. However, the post-hoc tests indicated that the highest dose tested (0.1 mg/kg) was inactive in the DA D2R KO mice but significantly decreased locomotor activity (to 42% of control levels) in the DA D2R WT mice (Fig. 3a). At low to intermediate doses, 7-OH-DPAT produced dose-related decreases in the locomotor activity of WT but not KO mice (Fig. 3b). The two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect of dose in the DA D2R WT mice [F(3,40) = 13.8, P < 0.001], whereas the effects of genotype [F(1,40) = 1.39, NS] and its interaction with dose [F(3,40) = 2.18, NS] were not significant.

Fig. 3.

Effects of dopamine agonists on locomotor activity in dopaminergic (DA) D2R wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice. Vertical axes: mean number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Horizontal axes: drug dose in mg/kg. Filled and open points represent activity counts for DA D2R WT and KO mice, respectively. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in four to six mice. Statistical significance of results versus vehicle (V) according to a Dunnett’s test in WT mice are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. No significant effects were observed in KO mice, (a) Effects of quinpirole, (b) effects of 7-OH-DPAT, (c) effects of PD 128907, (d) effects of U-91356A.

Increasing doses of PD 128907 also produced dose-dependent decreases in locomotor activity (Fig. 3c). A two-way ANOVA indicated significant effects of dose [F(4,50) = 11.1, P < 0.001] without effects of genotype [F(1,50) = 0.40, NS], though there was an effect of their interaction [F(4,50) = 10.1, P < 0.001]. The highest dose tested (1.0 mg/kg) was inactive in the DA D2R KO mice but decreased locomotor activity to 15% of control levels in the DA D2R WT mice (Fig. 3c). Genotype-dependent effects of U-91356A were found across a range of doses from 0.01 to 1.0 mg/kg (Fig. 3d). A repeated-measures of ANOVA indicated significant effects of dose [F(3,30) = 29.8, P < 0.001], genotype [F(1,30) = 23.8, P < 0.001], and their interaction [F(3,30) = 27.2, P < 0.001].

In general, there were no significant differences in locomotor activity levels in the DA D3R KO compared with WT mice (compare open to filled points above V in Fig. 4), though control levels for DA D3R KO mice were above those for WT mice in studies of U-91356A.

Fig. 4.

Effects of dopamine agonists on locomotor activity in dopaminergic (DA) D3R wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice.. Vertical axes: mean number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Abscissae: drug dose in mg/kg. Filled and open points represent activity counts for DA D3R WT and KO mice, respectively. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in six mice. Statistical significance of results versus vehicle (V) according to a Dunnett’s test in WT or KO mice are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. (a) Effects of quinpirole, (b) effects of 7-OH-DPAT, (c) effects of PD 128907, (d) effects of U-91356A.

Quinpirole (Fig. 4a) showed significant effects of dose [F(3,30) = 4.71, p < 0.01] without significant effects of genotype [F(1,30) = 1.37, P = 0.268], or the interaction of the two [F(3,30) = 2.90, P = 0.051], which approached significance. The highest dose tested (1.0 mg/kg) increased locomotor activity in the DA D3R KO mice. In contrast to the findings in the other lines of mice, none of the doses of 7-OH-DPAT decreased locomotor activity in DA D3R WT or KO mice, and overall effects of doses were not significant [F(4,40) = 0.802, NS]. In this comparison there was a significant effect of genotype [F(1,40) = 5.18, P < 0.05], with post-hoc tests indicating that the only significant difference (P = 0.012) between genotypes occurred at 0.3 mg/kg, which increased activity with substantial variability between subjects in DA D3R KO mice to a greater extent than WT mice (see Fig. 4b).

PD 128907 also dose-dependently decreased locomotor activity in the DA D3R WT and KO mice (Fig. 3c), and repeated measure ANOVA indicated significant effects of dose [F(3,30) = 6.76, P < 0.001]. In contrast, there were neither significant effects of genotype [F(1,30) = 1.17, NS], nor its interaction with dose [F(3,30) = 0.89, NS]. Similarly, U-91356A (Fig. 4d) decreased activity in a dose-related manner [F(3,27) = 17.1, P < 0.001]. With this compound, there were accompanying effects of genotype [F(1,27) = 5.75, P < 0.05], and their interaction [F(3,27) = 3.06, P < 0.05]. As noted above, there were differences in baseline activity levels in DA D3R WT and KO mice that contributed to the significant effects of genotype.

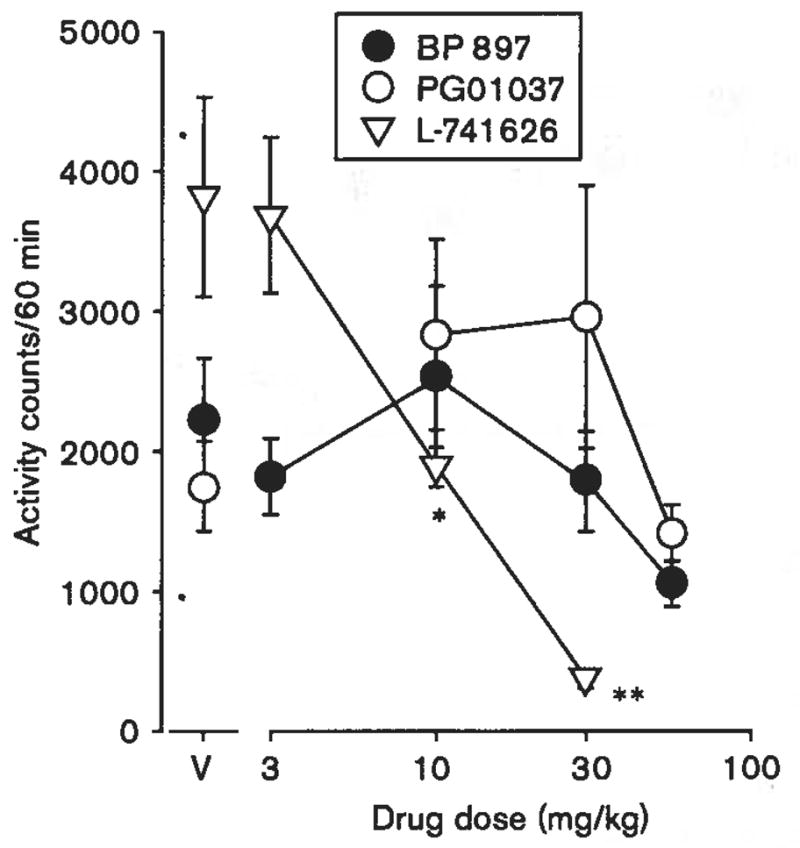

Effects of DA antagonists alone and in combination with DA D3R-preferring agonists on locomotor activity

Administered alone, the DA D2R-preferring antagonist, L-741626, produced dose-dependent statistically significant decreases in locomotor activity in Swiss–Webster mice [F(3,20) = 12.5, P < 0.001; Fig. 5, triangles; Table 3]. Either of the DA D3R antagonists, PG01037 (Fig. 5, open circles) or BP 897 (Fig. 5, filled circles), did not significantly affect locomotor activity across the range of tested doses.

Fig. 5.

Effects of dopamine antagonists on locomotor activity in Swiss–Webster mice. Vertical axes: mean number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Horizontal axes: drug dose in mg/kg. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in six to twelve mice. Statistical significance of results versus vehicle (V) according to a Dunnett’s test in wild-type mice are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Table 3.

Effects of L-741626 on locomotor activity in mice

| Treatment | Swiss–Webster mouse | DA D2R WT mouse | DA D2R KO mouse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 3820 ± 718 | 5650 ± 1030 | 2120 ± 460 |

| L-741626 3.0 mg/kg | 3680 ± 556 | 7510 ± 1470 | 2440 ± 747 |

| L-741626 10.0 mg/kg | 1891 ± 139* | 4810 ± 886 | 2290 ± 489 |

| L-741626 30.0 mg/kg | 379 ± 64.0** | 735 ± 119** | 660 ± 97.6** |

Values represent the average number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Each dose was examined in six subjects.

KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

Significant outcome of Dunnett’s test versus vehicle group is indicated as follows:

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

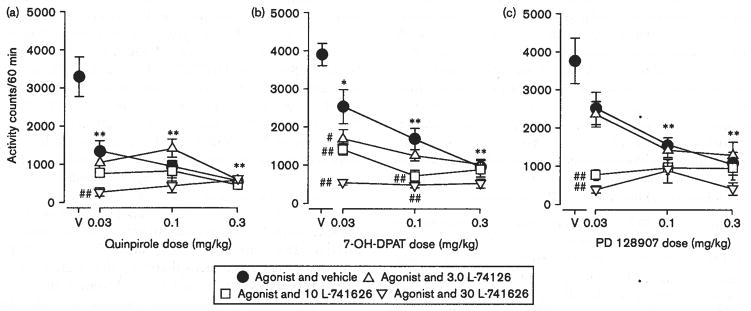

Pretreatments with L-741626 shifted the quinpirole dose-effect curve downward in a manner that depended on L-741626 dose [F(3,123) = 21.105, P < 0.001, compare open points to filled points in Fig. 6a]. There was also a significant effect of quinpirole dose [F(5,123) = 3.82, P < 0.005] and an interaction between the two drugs [F(15,123) = 2.67, P < 0.002]. L-741626 also shifted the 7-OH-DPAT (Fig. 6b) and PD 128907 (Fig. 6c) dose-effect curves downward. With each of these drug combinations there was a significant effect of L-741626 dose [with 7-OH-DPAT: F(3,64) = 20.7, P < 0.001; with PD 128907: F(3,122) = 13.5, P < 0.001], and a significant effect of the agonists [7-OH-DPAT: F(2,64) = 13.1, P < 0.001; PD 128907: F(5,122) = 5.88, P < 0.001]. There were also significant interactions between L-741626 doses and agonist dose [7–OH-DPAT: F(6,64) = 2.93, P < 0.02; PD 128907: F(15,122) = 2.36, P < 0.005].

Fig. 6.

Effects of combinations of quinpirole, 7-OH-DPAT, or PD 128907 with L-741626 on the locomotor activity of Swiss–Webster mice. Vertical axes: mean number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Horizontal axes: drug dose in mg/kg. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in six to nine mice. Statistical significance versus vehicle and vehicle (V) group (according to the Dunnett’s test) are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Statistical significance of a given dose of agonist and vehicle versus that dose with a dose of antagonist according to the Dunnett’s test are indicated as followis: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. (a) Effects of quinpirole, (b) effects of 7-OH-DPAT, (c) effects of PD 128907.

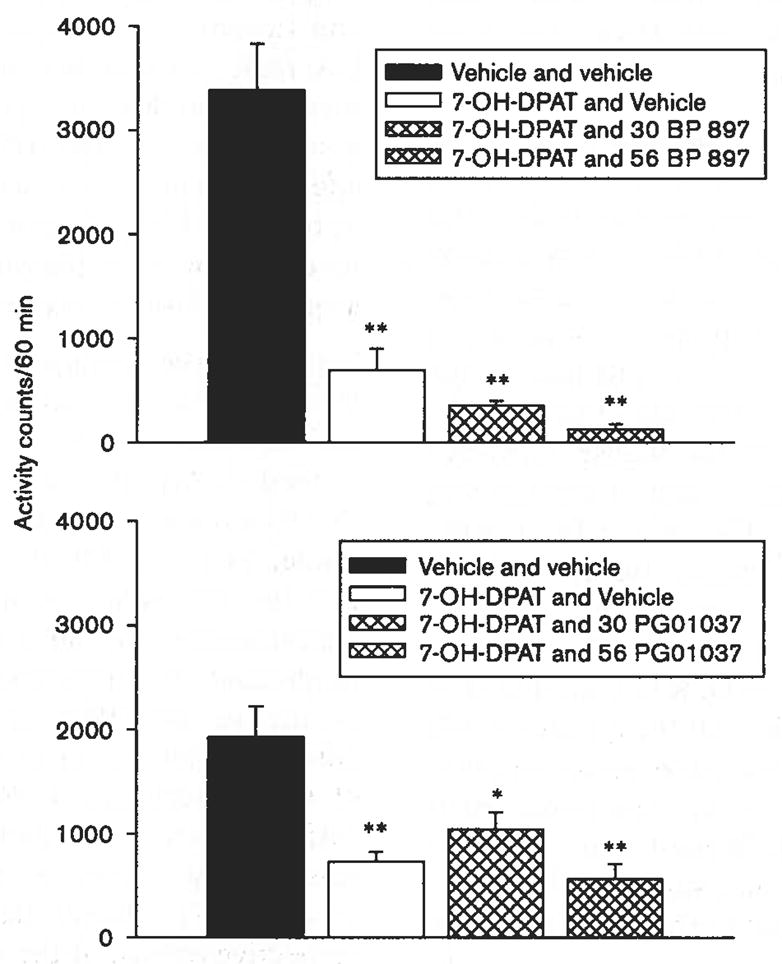

The potential antagonism of the decrease in activity produced by 1.0 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT by DA D3R antagonists, BP 897, and PG01037 was also examined in Swiss–Webster mice (Fig. 7). Each antagonist was studied at 30.0 and 56.0 mg/kg, the highest doses studied that did not produce effects were different from control when examined alone, and for PG01037 a higher dose (see Fig. 5). Each one-way ANOVA conducted on the data for either BP 897 [F(3,27) = 33.3, P < 0.001] or PG01037 [F(3,24) = 8.44, P < 0.001] was significant, with activity levels after 1.0 mg/kg 7-OH-DPAT significantly less than control levels. However the post-hoc tests indicated that neither antagonist at any of the doses tested significantly attenuated the effects of 1.0 mg/kg of 7-OH-DPAT.

Fig. 7.

Effects of combinations of 1 mg/kg 7-OH-DPAT with either BP 897 or PG01037 on the locomotor activity of Swiss–Webster mice. Vertical axes: mean number of locomotor activity counts during a 60-min observation period. Horizontal axes: drug dose in mg/kg. Vertical bars indicate ± SEM. Each dose was examined in six to eight mice. Statistical significance according to the Fisher’s least significant difference test of 7-OH-DPAT with vehicle versus vehicle and vehicle results are as follows: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. Differences between agonist and vehicle versus agonist and antagonist were not statistically significant according to the Fisher’s least significant difference test (P ≥ 0.18).

Discussion

In this study the DA agonists, 7-OH-DPAT, and PD 128907, produced dose-related increases in yawning in rats at low to intermediate doses, and less of an increase at the highest doses, as in earlier studies (Collins et al, 2005, 2007). In addition, low doses of the drugs produced a decrease in locomotor activity that resolved at higher doses. In contrast, yawning was not produced in mice by any doses of several DA agonists, but was reliably produced by physostigmine. The effects of physostigmine indicate that the yawning response can be induced in mice, but does not appear to be activated by a variety of drugs that induce yawning in rats through DA D3R mechanisms.

Collins et al. (2005) suggested that the inhibition of yawning that appears at higher doses of DA agonists and contributes to the descending limb of the biphasic dose-effect curve appears to be mediated by DA D2R agonist actions. In their study, the DA D2R preferring antagonist L-741626, selectively antagonized the descending limb of the PD 128907 and quinelorane dose-effect curves. This effect was also obtained without appreciable change in the ascending limb of the dose-effect curve for a variety of other DA D3R-preferring agonists, consistent with these two dopamine receptors producing opposing effects on yawning (Collins et al, 2007). Thus, the possibility exists that the absence of yawning in mice is because of prepotent DA D2R mediated inhibitory effects that preclude the expression of an otherwise DA D3R mediated stimulation of yawning.

We examined the hypothesis that prepotent DA D2R-mediated effects interfered with the expression of a DA D3R-mediated induction of yawning by examining mice with a genetic deletion of the DA D2R, and by administering the putative DA D2R selective antagonist, L-741626. According to the hypothesis, eliminating actions either by genetic deletion or by pharmacological blockade of the receptor would be expected to show a full expression of yawning behavior in the mouse. However, neither DA D2R KO nor WT mice showed any yawning after administration of either 7-OH-DPAT or PD 128907. In addition, casual observations during studies of interactions of L-741626 and the agonists on locomotor activity did not show instances of yawning. Furthermore, the lack of difference between DA D2R WT and KO mice in the effects of physostigmine indicates the absence of a generalized DA D2R-mediated inhibitory effect on yawning. Thus, the absence of yawning appears unrelated to the relative potencies of DA D2R-mediated and D3R-mediated actions in the mouse and suggests differences between rats and mice with regard to the pharmacological actions of DA D3R agonists.

Across the range of doses that were examined, several of the DA agonists produced a decrease in locomotor activity in mice and rats. In rats, the decreases in activity were obtained over a restricted range of doses. In particular with 7-OH-DPAT a significant effect at 0.03 mg/kg was not obtained at three-fold higher or three-fold lower doses. In contrast, the relation of this effect to dose in mice was remarkable in that decreases were obtained across a relatively wide range of doses, from 1000-fold to 10 000-fold with 7-OH-DPAT and quinpirole. There were substantial differences among the agonists with respect to effects at the higher doses in mice. For PD 128907, none of the higher doses returned activity to control levels, and with U-91356A, the highest dose studied only returned activity to control levels. The variability across drugs in the effects of the highest doses, and the remarkably wide range of doses over which the decreases in locomotor activity were obtained, prompted the present focus on the pharmacology of the decreases in activity. The observation that some, but not all DA agonists produced hyperactivity at the highest doses tested tempts an interpretation of differences among the drugs with respect to high-dose toxicity, however, that suggestion requires further investigation.

A low-dose inhibition of locomotor activity that is resolved at higher doses has been reported in the past (e.g. Daly and Waddington, 1993; Pugsley et al., 1995; Bristow et al, 1996; Maj et al, 1999), and has been variously attributed to presynaptic DA D2R activity (e.g. Millan et al, 2004) and actions mediated by the DA D3R (e.g. Gilbert and Cooper, 1995; Bristow et al, 1996; Shafer and Levant, 1998; Maj et al, 1999). These studies with DA D2R KO and WT mice suggest that the effect is mediated, at least in part, by the DA D2R, as it was obtained in the DA D2R WT but not KO mice. In addition, decreases in locomotor activity were obtained in both DA D3R WT and KO mice. The DA D2R actions mediated by both presynaptic or postsynaptic DA D2R requires additional studies.

None of the antagonists studied were effective in blocking the agonist-induced decreases in locomotor activity obtained at the low to intermediate doses. Indeed L-741626, rather than antagonizing, added to the locomotor decreasing effects of 7-OH-DPAT, quinpirole, and PD 128907. The lack of antagonism may not be surprising given the multitude of pharmacological agents that can decrease locomotor activity, and by implication the presumed mechanisms that may contribute to the effect on locomotor activity. Studies of antagonist effects in mutant mice may elucidate some of these mechanisms. Nonetheless, an antagonist with sufficient selectivity such as what has been reported at least among dopamine receptor subtypes (e.g. Grundt et al, 2007), should have blocked the effects of its respective agonist, if the agonist was sufficiently selective in producing its effects. Despite significant effects of genotype in the effects of L-741626 on DA D2R mutant mice, the differences in sensitivity to the effects of L-741626 itself were relatively small in the two lines of mice. That finding, along with the general lack of antagonism of the effects of the agonists underscores the extant need for more selective pharmacological tools, both agonists and antagonists, to study dopaminergically-mediated behavioral effects better.

These studies document significant differences in the pharmacology of DA agonists in mice and rats. The most pronounced of these differences is the absence of yawning induced by the agonists in the mouse. Although yawning can be induced through other mechanisms in the mouse, it appears that yawning will not provide an in-vivo indication of DA D3R activation in the mouse. PD 128907 was different from the other DA agonists in that the decreases in locomotor activity were not resolved at high doses of the drug. Mechanisms contributing to the differences in the pattern of dose-effects on locomotor activity are not presently clear though it seems likely that these differences reflect differences in potencies for effects contributing to the decreases and the increases at higher doses.

In summary, the DA D3R preferring agonists, 7-OH-DPAT, and PD 128907, produced a biphasic stimulation of yawning in rats and a biphasic inhibition of locomotor activity. In contrast, these effects were different in mice; yawning was not produced by DA agonists, and the decreases in locomotor activity were characteristically obtained over a relatively broad range of doses. The decreases in locomotor activity appear to be because of the actions of the drugs at the DA D2R. These results are not inconsistent with earlier results indicating opposing modulation of yawning by the DA D3R and D2R in rats, though further studies on the role of the DA D3R in mice are clearly necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Patty Ballerstadt for administrative assistance. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and USPHS NIDA grants DA 020669 (J.H.W., Principal Investigator), DA17323 (M.X, Principal Investigator), and F 013771 (J.H.W, Principal Investigator). Some of the data were reported at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, Atlanta, Georgia, USA (October, 2006).

References

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Rostene W, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D3 receptor agonists produce similar decreases in body temperature and locomotor activity in D3 knock-out and wild-type mice. Neuropharmacology. 1999a;38:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay D, Depoortere R, Perrault G, Borrelli E, Sanger DJ. Dopamine D2 receptor knock-out mice are insensitive to the hypolocomotor and hypothermic effects of dopamine D2/D3 receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1999b;38:1389–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow LJ, Cook GP, Gay JC, Kulagowski JJ, Landon L, Murray F, et al. The behavioural and neurochemical profile of the putative dopamine D3 receptor agonist, (+) PD 128907, in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Witkin JM, Newman AH, Svensson KA, Grundt P, Cao J, Woods JH. Dopamine agonist-induced yawning in rats: a dopamine D3 receptor-mediated behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:310–319. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins GT, Newman AH, Grundt P, Rice KC, Husbands SM, Chauvignac C, et al. Yawning and hypothermia in rats: effects of dopamine D3 and D2 agonists and antagonists. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:159–157. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly SA, Waddington JL. Behavioural effects of the putative D-3 dopamine receptor agonist 7-OH-DPAT in relation to other D-2-like agonists. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:509–510. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoortere R, Perrault G, Sanger DJ. Behavioural effects in the rat of the putative dopamine D3 receptor agonist 7-OH-DPAT: comparison with quinpirole and apomorphine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:231–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02246662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geter-Douglass B, Katz JL, Alling K, Acri JB, Witkin JM. Characterization of unconditioned behavioral effects of dopamine D3/D2 receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DB, Cooper SJ. 7-OH-DPAT injected into the accumbens reduces locomotion and sucrose ingestion: D3 autoreceptor-mediated effects? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;52:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00113-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt PG, Carlson EE, Cao J, Bennett CJ, McElveen E, Taylor M, et al. Novel Heterocyclic Trans Olefin Analogues of N-4-[4-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl]butylarylcarboxamides as selective probes with high affinity for the dopamine D3 receptor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:839–848. doi: 10.1021/jm049465g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundt PG, Husband SLJ, Luedtke RR, Taylor M, Newman AH. Analogues of the dopamine D2 receptor antagonist L741, 626: binding, function, and SAR. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren B, Urbá-Holmgren R. Interaction of cholinergic and dopaminergic influences on yawning behavior. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 1980;40:633–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JN, Millan MJ. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as therapeutic agents. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:917–925. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MA, Rubinstein M, Asa SL, Zhang G, Saez C, Bunzow JR, et al. Pituitary lactotroph hyperplasia and chronic hyperprolactinemia in dopamine D2 receptor-deficient mice. Neuron. 1997;19:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzewa RM, Brus R. Is dopamine-agonist induced yawning behavior a D3 mediated event? Life Sci. 1991;48:PL129. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90619-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levant B. The D3 dopamine receptor: neurobiology and potential clinical relevance. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj J, Rogóz Z, Skuza G. The anticataleptic effect of 7-OH-DPAT: are dopamine D3 receptors involved? J Neural Transm. 1999;106:1063–1073. doi: 10.1007/s007020050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Seguin L, Gobert A, Cussac D, Brocco M. The role of dopamine D3 compared with D2 receptors in the control of locomotor activity: a combined behavioural and neurochemical analysis with novel, selective antagonists in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:341–357. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1770-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogilnicka E, Klimek V. Drugs affecting dopamine neurons and yawning behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1977;7:303–305. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(77)90224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piercey MF, Moon MW, Sethy VH, Schreur PJKD, Smith MW, Tang AH, VonVoigtlander PF. Pharmacology of U-91356A, an agonist for the dopamine D2 receptor subtype. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;317:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AH, Grundt P, Nader MA. Dopamine D3 receptor partial agonists and antagonists as potential drug abuse therapeutic agents. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3663–3679. doi: 10.1021/jm040190e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard LM, Logue AD, Hayes S, Welge JA, Xu M, Zhang J, et al. 7-OH-DPAT and PD 128907 selectively activate the D3 dopamine receptor in a novel environment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:100–107. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugsley TA, Davis MD, Akunne HC, MacKenzie RG, Shih YH, Damsma G, et al. Neurochemical and functional characterization of the preferentially selective dopamine D3 agonist PD 128907. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1355–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogóz Z, Skuza G. Repeated imipramine treatment enhances the 7-OH-DPAT-induced hyperactivity in rats: the role of dopamine D2 and D3 receptors. Pol J Pharmacol. 2001;53:571–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevak RJ, Koek W, Galli A, France CP. Insulin replacement restores the behavioral effects of quinpirole and raclopride in streptozotocin-treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1216–1223. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.115600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer RA, Levant B. The D3 dopamine receptor in cellular and organismal function. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;135:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s002130050479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347:146–151. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirelli E, Reggers J, Terry P. Dopamine D2-like receptor agonists in combination with cocaine: absence of interactive, effects on locomotor activity. Behav Pharmacol. 1997;8:147–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Koeltzow TE, Tirado G, Moratalla R, Cooper DC, Hu X-T, et al. Dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice exhibit increased behavioral sensitivity to concurrent stimulation of D1 and D2 receptors. Neuron. 1997;19:837–848. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]