Abstract

The development of preventive interventions targeting adolescent problem behaviors requires a thorough understanding of risk and protective factors for such behaviors. However, few studies examine whether different cultural and ethnic groups share these factors. This study is an attempt to fill a gap in research by examining similarities and differences in risk factors across racial and ethnic groups. The social development model has shown promise in organizing predictors of problem behaviors. This article investigates whether a version of that model can be generalized to youth in different racial and ethnic groups (N = 2,055, age range from 11 to 15), including African American (n = 478), Asian Pacific Islander (API) American (n = 491), multiracial (n = 442), and European American (n = 644) youth. The results demonstrate that common risk factors can be applied to adolescents, regardless of their race and ethnicity. The findings also demonstrate that there are racial and ethnic differences in the magnitudes of relationships among factors that affect problem behaviors. Further study is warranted to develop a better understanding of these differential magnitudes.

It is estimated that about one half of youth aged 10–17 engage in problem behaviors such as delinquency, interpersonal violence, substance use, and risky sexual behavior (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2000). Despite the evidence that the prevalence of some problem behaviors is declining, a significant number of youth continue to engage in behaviors that place them at risk. In addition, the impact of problem behaviors among youth is not limited to adolescence. Although the frequency and severity of some problem behaviors (e.g., violent and delinquent behaviors) tend to decrease after adolescence and young adulthood (Moffitt, 1993), some problem behaviors initiated during adolescence (e.g., substance use) continue to increase into adulthood (CDC, 2000). Further, for some youth, involvement in these adolescent behaviors persists, resulting in multiple negative outcomes over the life course. Such outcomes might include substance abuse and dependence, and in some cases, mortality. Thus, investigation of the predictors of youth problem behaviors is important for efforts to prevent these problems before they occur and to reduce the severity of these problems.

There is evidence that many problem behaviors co-occur, and this finding is consistent across both gender and age (Thornberry, Huizinga, & Loeber, 1995). For example, substance use has been found to be associated with violence, delinquency, academic underachievement, and school problems (Huizinga & Jakob-Chien, 1998; Newcomb, Maddahain, & Bentler, 1986). A relationship between school problems and delinquency has also been demonstrated (Maguin & Loeber, 1995). Additionally, almost all youth who are incarcerated report having been involved with drugs (Dryfoos, 1998). Further, many of these problem behaviors have been found to share common antecedents (Howell, Krisberg, Hawkins, & Wilson, 1995). These findings suggest that considerable commonalities exist between patterns of relationships among problem behaviors and the factors related to such problem behaviors.

In this article, we focus on two problem behaviors: interpersonal violence and substance use. Substance use and violent behaviors are directly linked to alcohol-related motor vehicle accidents, the leading cause of death among young people, as well as to a high number of juvenile arrests (Dryfoos, 1998). The prevalence of these problem behaviors is quite high. Based on a national sample of high school students completing the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000) found that 36% of students reported involvement in physical fights more than once during the 12 months prior to the survey. Seventeen percent of students carried weapons within 30 days of the survey. Regarding substance use, more than 71% of students have tried cigarettes, 42% have smoked marijuana, 27% have tried a cigar, 7% reported trying cocaine, and 80% have drunk alcohol. Among youth, the prevalence of lifetime and current cocaine use has increased in recent years, and the age for initiation of substance use is getting younger (CDC, 2000; Dryfoos, 1998). Research suggests that youth involved in both drug use and delinquency are more likely to become drug abusers in adulthood (White & Labouvie, 1994).

Racial and Ethnic Variation in Etiology of Youth Problem Behaviors

In the last two decades, numerous studies have examined the etiology of adolescent problem behaviors. However, scholars only recently started examining whether different cultural and ethnic groups share common risk and protective factors for these behaviors. Considerable differences might exist across the structural environments of different racial and ethnic groups (McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, & Wilson, 2000). In addition, each racial and ethnic group may differ in the ways that it socializes children in family contexts (Krishnakumar, Buehler, & Barber, 2003). Theories attempting to explain and predict youth problem behaviors have been tested primarily with Caucasian male samples or with samples undifferentiated by race and gender (Muuss, 1996). Some have argued that these theories may not generalize to ethnic minorities because they may not recognize the cultural and contextual uniqueness of different ethnic groups (Spencer, Swanson, & Cunningham, 1991). Thus, determining whether these theories can help explain problem behaviors among ethnic minority youth is one step in generalizing existing research to address the needs of these youth.

Empirical research is inconsistent on etiological factors in racial and ethnic group differences. Some studies demonstrate significant differences in factors related to children’s behaviors across racial and ethnic groups (e.g., Deater-Deckart, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1996; Gutman & Eccles, 1999). For example, McLeod and Nonnemaker (2000) report that antecedent conditions differ significantly across racial and ethnic groups. The differences are also observed for processes that mediate psychological well-being of children, e.g., the weaker effect of poverty and the stronger effect of mother’s self-esteem for African-American children. By contrast, other research fails to find empirical support for these racial and ethnic variations (e.g., Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002; Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd, 2002). The conflicting findings call for more sustained efforts in this area.

Few of the studies examining similarities and differences of etiological factors across racial and ethnic groups have examined Asian Pacific Islander (API) Americans (exceptions, Catalano, Morrison, Wells, Gillmore, Iritani, Hawkins, 1992; Kim & Ge, 2000). Consequently, although API is one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the U.S., they remain one of the least studied. The same is also true of multiracial youth (exceptions, Conger, 1976; Shakib, Mouttapa, Johnson, Ritt-Olson, Trinidad, Gallaher et al., 2003). The numbers of multiracial children and adolescents have grown rapidly, but despite their self-identification as multiracial, it is often the case that they are not regarded as a distinct group. Thus, little is known about the determinants and consequences of problem behaviors in API Americans and multiracial groups.

In addition, studies differ in the ways they examine racial and ethnic differences. Although several studies explicitly test the interactions between different predictors and ethnicity (e.g., McLeod & Nonnemaker, 2000), others consider ethnicity as an exogenous variable, or examine each group separately (e.g., McCoy, Frick, Loney, & Ellis, 1999). Such approaches do not address investigations of the moderating effects of race and ethnicity. By more explicitly and consistently testing moderating effects of race and ethnicity, researchers will gain a better understanding of the differences between groups in the magnitudes of relationships between etiological factors and youth outcomes.

This article examines an existing model that has shown promise in predicting adolescent problem behaviors: the social development model (SDM) (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985). The study seeks to determine whether the SDM can generalize to youth in different racial and ethnic groups including API Americans and multiracial youth; it also analyzes whether and how the relationships between constructs are moderated by race and ethnicity. Specifically, we examine a part of the SDM that specifies the processes of social development in the family across racial and ethnic groups. This partial SDM includes family socialization, bonding to parents, and youth beliefs as predictors of problem behaviors. Parent–child relationships, parenting practices, and other family-related factors have emerged as key determinants of adolescent outcomes and studies show that parents and family remain important forces in the socialization of adolescents through high school (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). The results from this study can serve to inform the development of preventive interventions that support the healthy development of children from various groups.

Social Development Model

The Social Development Model (SDM) (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hawkins & Weis, 1985) is a general theory of human behavior that specifies the role of developmental processes in predicting outcomes of both prosocial and problem behaviors. The SDM is a synthesis of three extant theories: control theory (Hirschi, 1969; Reiss, 1951), social learning theory (Akers, Krohn, Lanza-Kaduce, & Radosevich, 1979; Bandura, 1977), and differential association theory (Matsueda, 1982; Sutherland, 1973). According to the SDM, individuals learn patterns of behavior, prosocial, or antisocial, in different socializing units or groups (such as family, peer, school, and community). With socialization that provides consistent opportunities for involvement, skills for involvement, and recognition of involvement, a child becomes bonded to the socializing units. The child is likely to adopt social beliefs, prosocial, or antisocial, consistent with the predominant behaviors, norms, and values held by those to whom the child is bonded, and the child’s social beliefs predict his or her behaviors.

The SDM further posits that one’s position in the social structure, determined by socioeconomic status (SES), race, gender, and age, has an indirect effect on behavior outcomes through its impact on external constraints and socialization processes. For example, coming from a low SES background is hypothesized to increase one’s opportunities for antisocial involvement because of the higher prevalence of visible crime in low-income neighborhoods. One’s position in the social structure also impacts external constraints—the formal and informal rules for behavior. External constraints are constraints that others or institutions put on an individual’s behavior. As such, external constraints include the clarity of rules, laws, and norms in various socializing units as well as monitoring of behavior and the degree of consistency and immediacy of the sanctions imposed by these socialization units. For example, during early adolescence, family management practices and peer norms represent the dominant external constraints. The SDM posits that family management processes, such as rules, supervision, or monitoring in the family, affect family socialization processes including increasing the likelihood of pro-social opportunities and decreasing the likelihood of antisocial opportunities. The immediacy and consistency of sanctions imposed affects perceived rewards for family involvement.

The SDM has been shown to predict early antisocial behavior among elementary school children (Catalano, Oxford, Harachi, Abbott, & Haggerty, 1999). It is also predictive of later adolescent substance use (Catalano, Kosterman, Hawkins, Newcomb, & Abbott, 1996), adolescent alcohol misuse (Lonczak, Huang, Catalano, Hawkins, Hill, Abbott et al., 2001), and violence (Huang, White, Kosterman, Catalano, & Hawkins, 2001). These studies provide empirical evidence for the relationships hypothesized by the SDM across various age groups.

Partial SDM

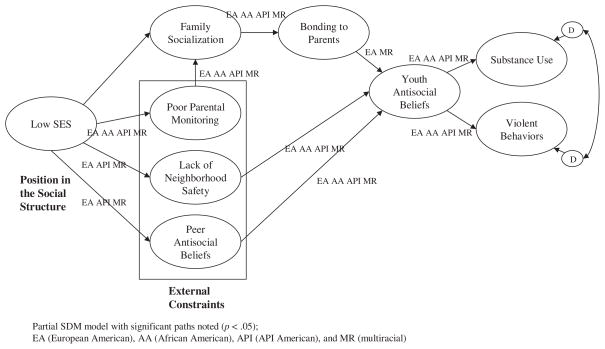

This study examines a part of the SDM that specifies the pathways from SES, external constraints, and the processes of social development in the family, to youth beliefs that lead to youth outcomes (Figure 1). SES is the most consistent and powerful predictor of adolescent success and well being (National Research Council Panel on High-Risk Youth, 1993). However, the effects of the exogenous variables, including SES and external constraints, have been understudied in testing the SDM. This study examines the influence of SES as mediated by the SDM processes.

FIGURE 1.

A partial social development model.

Poor parental monitoring and peer antisocial beliefs are external constraints of the partial SDM. Parental monitoring is one of the most significant predictors of youth outcomes (Huebner & Howell, 2003). Poor monitoring is hypothesized to be negatively related to family socialization. Good parental monitoring increases positive parental involvement and interaction with children. It also increases positive reinforcement for behavior that increases child bonding with parents (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Peer norms are also a strong predictor of youth outcomes (Thornberry & Krohn, 1997) and included in the partial SDM. We attempt to expand the understanding of external constraints beyond poor monitoring and peer social beliefs by modeling the effects of neighborhood environments. Neighborhood context can be significant in youth development (Brook, Nomura, & Cohen, 1989). The current study postulates that neighborhood context constrains behavior both formally and informally. Perceptions of neighborhood safety are used as a proxy for external constraints, because the perception of high crime or lack of safety in a neighborhood indicates that rules and monitoring behaviors are ineffective or absent. The SDM posits that external constraints are mediated by socialization processes and the beliefs of youth. The dataset used to test this partial SDM does not measure peer and neighborhood socialization processes expected to mediate the peer and neighborhood external constraints; therefore, paths are drawn directly to youth beliefs.

The original SDM defines family socialization within three distinct constructs: opportunities, involvement, and rewards. However, Lonczak et al., (2001) find substantial common variance in these socialization constructs. They further show that these constructs together can capture the socialization process as a single construct and that the socialization process significantly affects bonding to social units (Lonczak et al., 2001). Accordingly, this partial SDM examines family socialization as a single construct. Family socialization includes democratic parenting styles, level of communication, and positive reinforcement, which are behavioral aspects of the family processes. Bonding, on the other hand, is a psychological and affectionate aspect of the family processes (Mistry et al., 2002). Bonding to prosocial parents is inversely related to negative outcomes (Greenberg, 1999), and the relationship between bonding and negative outcomes is mediated by one’s belief system (Catalano et al., 1996). Simultaneously testing the family factors and the exogenous variables can help improve our understanding of how these factors relate to youth problem behaviors.

Although the SDM has been tested with samples that include youth from various racial and ethnic groups, the similarities and differences in model fit for different groups have not been explicitly investigated. This study examines whether the partial SDM is useful for understanding the problem behaviors of urban ethnic minority youth. The SDM hypothesizes that race is one of the exogenous variables. In this article, race is examined as a moderator. This allows investigation of the utility of the partial SDM in each racial and ethnic group. It also enables an examination of differences and similarities in the relationships among the model’s factors across groups.

Racial and Ethnic Group Differences in the Partial SDM

Although there are several conceptual and theoretical propositions for the variations of etiology for child development across racial and ethnic groups, there is no clear consensus on how they differ (McLoyd et al., 2000). As described above, empirical findings are mixed in this area of study. In testing the partial SDM across groups, hypotheses were developed in light of both theoretical propositions and empirical findings.1 First, we hypothesized that the partial SDM would fit well across groups. A majority of existing studies report substantial commonality of etiological factors. These factors include parental monitoring (Huebner & Howell, 2003), the effects of low-income status on parenting behaviors (Gutman & Eccles, 1999), the relationship between beliefs and youth outcomes (Gottfredson & Koper, 1996), peer norms (Griesler, Kandel, & Davies, 2002), and the effect of neighborhood factors (Hill & Herman-Stahl, 2002). In addition, some of the etiological processes may be universal. For example, the family’s income level can determine the types of neighborhood and peer groups to which children are exposed. These, in turn, are likely to influence children’s social beliefs. Because such influences are common social phenomena (Sampson, 1997), we hypothesized that these relationships would occur similarly across groups.

Discussions of racial and ethnic group differences are mostly related to cultural variations in parenting processes. Family socialization and parenting strategies often vary across ethnic groups (Kagitçibasi, 1996). For example, relative to European American (EA) parents, there is less evidence for authoritative parenting among API (APIA) and African American (AA) parents (Huebner & Howell, 2003; Shakib et al., 2003). APIA and AA parents are less likely to involve their children in family decision making and to use praise (Kagitçibasi, 1996). However, this style of parenting may not necessarily be linked to a lower level of parental bonding or adverse child outcomes (Chao, 1994; Rudy & Grusec, 2001). Strict discipline may not lead to externalizing behaviors among AA youth (Deater-Deckart et al., 1996), and authoritarian parenting may not lead to lower school performance among APIA youth (McLoyd et al., 2000). Thus, we hypothesized that, relative to majority youth, the relationship between family socialization and bonding to parents would be weaker among AA and APIA youth. Moreover, studies suggest that relationship with parents may have a stronger effect among minority youth than majority youth, suggesting close parent–child relationships provide a greater buffering effect for minority youth (Spencer et al., 1991). Minority children are more likely to face structural and social adversities outside the family; the parental roles of protector and gatekeeper are critical (Spencer et al., 1991). Thus, we hypothesized that the relationship between parental bonding and youth beliefs would be stronger among AA and APIA youth than EA youth.

Studies on multiracial children are very limited (Cooney & Radina, 2000). However, more similarities than differences are found in comparing the parenting characteristics of multiracial and EA families. This is also the case with the relationships between those parenting characteristics and children’s outcomes (Cooney & Radina, 2000; Shakib et al., 2003). Thus, we did not expect many significant differences between multiracial and EA youth in the relations of family constructs to youth outcomes. The exception to this is the relationship between bonding to parents and youth beliefs. Winn and Priest (1993) report that social prejudice and perceived racism are recurring themes in their interviews with multiracial youth. Thus, monoracial ethnic minority youth and multiracial youth may experience common social adversities. Accordingly, we hypothesized that a positive parent–child relationship measured by bonding to parents would be more strongly related to youth beliefs among multiracial youth than among EA youth.

METHODS

Overview of Project and Sample Selection

The data for this study were collected in 1997 as part of the Minority Youth Health Project, the Seattle site of a seven-location study. The primary aim was to improve minority youth health by focusing on preventing problem behaviors in four interrelated areas: interpersonal violence, adolescent pregnancy, sexually transmitted disease, and substance use. The seven-site study was an experimental test of a community-based program that sought to intervene at neighborhood and individual levels through the creation of community action boards and youth development workshops. The target samples for the project were minority youth between the ages of 10 and 14.

The 1997 data were collected after the delivery of community-based interventions.2 Data were collected using a survey conducted at four middle schools in Seattle. Racial and ethnic composition of the Seattle Public School District in 1993–1994 (obtained from the District) was 40.6% EA, 25.4% APIA, 23.7% AA, 6.7% Latin Americans (including Asian/Latino, Black/Latino, White/Latino), and 3.6% Native Americans. Four of the middle schools with the highest percentages of ethnic minority student enrolled were chosen for this study to examine the effects of neighborhood organizing in communities of color. Families were alerted to the survey by an introductory letter mailed to parents of all enrolled students. Parents declined their child’s participation by returning a postcard. This procedure was approved by IRB. Project staff administered the survey during two separate class days at each of the middle schools. The survey was self-administered during a 50-minute class period. Those students who declined to participate were asked to remain in the classroom reading other material during the survey. Project staff remained in each of the classrooms during survey administration; teachers did not. Of the total number of enrolled students at the four schools (N = 2,777), 574 (20.7%) students declined to participate in the study or were absent. As a result, 2,203 (79.3%) students completed the survey. Of this sample, 68.9% self-identified as ethnic minorities (N = 1,519).

Sample Description

The average age of the students was 12.7 years (SD = 1.00). Approximately one third was in each of the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades. Slightly more than 50% were girls. Youth identified as APIA (n = 491, 22.3%), AA (n = 478, 21.7%), multiracial (n = 442, 20.1%), EA (n = 644, 29.2%), Native American, and Latin American. This analysis omitted Native and Latin Americans because of their small numbers. The result is a total sample size of 2,055 adolescents. Slightly more than 50% of the sample reported that their biological parents were married or living together; 20.5% reported that they were born outside of the U.S.; and 38.9% were from low-income households. Low-income status was based on reports of receiving food stamps or eligibility for the federal free or reduced school-lunch program.

Measures

The constructs from the SDM (Figure 1) were examined as latent variables. Multiple indicators, mostly from multiple-item scales, were developed to reflect these latent constructs. Typically, two or three items were used to create each indicator.3 If a youth responded to at least half of the items composing an indicator, the mean of the items making up that indicator was computed as the value of the indicator. In all coding, higher scores reflected more of the indicated construct. The α reliability coefficients provided are for the overall factors, not the indicators.

Low SES was assessed by four questions concerning household receipt of food stamps or free student lunches, and whether the mother or father finished high school. These items have been used in numerous studies to measure SES, demonstrating acceptable reliability and validity (e.g., Catalano, Hawkins, Krenz, Gillmore, Morrison, Wells et al., 1993; Gottfredson & Koper, 1996). The response options were “Yes” and “No.” The α reliability coefficient was .61. Two indicators (SES1 and SES2) were created for this construct.

External constraints

Poor parental monitoring was assessed by two items asking about parental monitoring and supervision: “How often do your parents know where you are and who you are with?” and “In the evenings, how often is there at least one adult with you at home?” Knowing the whereabouts of children and knowing what they are doing have been most frequently used as indicators of parental monitoring (Shumow & Lomax, 2002). Although Stattin and Kerr (2000) show that much of the effect of parental monitoring is because of child disclosure rather than active parental control, their measures of child disclosure and parental monitoring are highly correlated (.70). We feel that our measure is an adequate proxy for child disclosure or the more traditional parental monitoring construct. Response categories for these questions ranged from (1) “All the time” to (4) “Rarely or never.” Each item served as an indicator of the latent construct (PPM1, PPM2).

Lack of neighborhood safety was assessed by five items asking students about their perceptions of safety in their neighborhoods, e.g., “People in my neighborhood get robbed,” and “People get in fights and get beat up.” The response options ranged from (1) “Not at all” to (4) “A lot.” The α reliability coefficient was .73. Two indicators (NS1 and NS2) defined this construct.

Peers’ antisocial belief was assessed by six items regarding the youth’s perceptions of peers’ beliefs about a range of behaviors. Examples include: “Most people my age think it is OK to get drunk once in a while” or “to use drugs.” The response options ranged from (1) “Not true” to (3) “Very true.” The α reliability coefficient was .86. Three indicators (PBL1–PBL3) were created for this construct.

Family socialization was assessed by five items that include involvement in family and rewards from parents. Sample items include: “How often do your parents ask what you think before they make family decisions?”, “When you disagree with your parents, how often can you talk things out?”, and “How often do your parents praise you for doing good things?” The response options ranged from (1) “Rarely or never” to (4) “All of the time.” The α reliability coefficient was .82. Two indicators (FS1 and FS2) were created.

Bonding to parents was assessed by four or eight items, depending on whether the student lived in a one- or two-parent household. The items asked for descriptions of the student’s closeness with his or her mother and father, and sought to assess how much the student wants to be like the mother or father figure. Sample items include: “How much of the time do you feel very close to your mother/father?” and “How often do you share thoughts and feelings with him/her?” The response options ranged from (1) “Rarely or never” to (4) “All of the time.” The α reliability coefficient was .87. Three indicators (BP1–BP3) were created.

Youth antisocial belief was assessed by seven items asking the students to describe their attitudes regarding behaviors such as drinking, using illegal drugs, and carrying a gun or knife. Examples include: “It is okay for people my age to drink alcohol once in a while,” and “It is okay for people my age to carry a gun or knife.” The response options ranged from (1) “Strongly disagree” to (4) “Strongly agree.” The α reliability coefficient was .89. Three indicators (YBL1–YBL3) defined this construct.

Problem behavior outcome variables

Substance use was assessed by seven items tapping frequency of use in the month, 3 months, or year prior to survey depending on the substance.4 Substances included alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, inhalants, cocaine, and crack. Questions also assessed frequency of binge drinking, getting high, and getting drunk. The α reliability coefficient of the items was .89. Because response options varied, scores to the individual items were standardized to a distribution with a mean of 0 and a SD of 1. Three indicators (SUB1–SUB3) were created.

Violent behaviors were assessed by eight items regarding the frequency in the month, 3 months, and year prior to survey of each of the following: threatening to beat up or to stab someone, physical fighting, serious injury from physical fighting, carrying a knife or gun, or shooting someone. The α reliability coefficient was .81. The response options varied, so scores of the individual items were standardized in the same manner as for the substance use outcome. Three indicators (VIO1–VIO3) defined this latent construct.

Self-identification of race and ethnicity

All respondents were asked the following five questions in succession: “Are you (a) Black or AA, (b) Native American or American Indian or Alaska Native, (c) Asian or Pacific Islander, (d) Caucasian or White, and (e) Hispanic or Latino?” Individuals were allowed to answer “yes” or “no” to each of the questions. Respondents also were given the opportunity to specify an “other” category. A race variable was subsequently computed to categorize students as AA, APIA, EA, Latin American, Native American, and multiracial (for those youth who identified themselves as being of more than one race or ethnicity).5

Analytic Strategy

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation was used to estimate the partial SDM (Figure 1) using the EQS program (EQS 5.7b) (Bentler, 1998). As recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), a two-step process was used. In the first step, using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the fit of the measurement model was established to assess reliability and validity of the measures used (Shumow & Lomax, 2002). We also determined whether the measurement model is invariant across racial and ethnic groups. In the second step, we tested the structural model to determine whether the hypothesized relationships among the model variables are invariant across groups.

Byrne (1994) suggests establishing a baseline model for each group before investigating group differences. For both measurement and structural models, we first ran the models for each group separately. In the CFA models, all factor loadings and factor correlations were freely estimated while factor variances were constrained to 1. In the structural models, one of the indicators to each latent variable was fixed to 1. This was done in order to scale the factors while factor variances and the hypothesized paths are freely estimated. In addition, the disturbance terms of two outcome variables, substance use and violent behaviors, were allowed to covary in order to account for conceptual correspondence between the two constructs.

Multiple-group analyses (single four-group SEM) in which we compared two nested models (i.e., unconstrained and constrained models) were then run for both measurement and structural models (Byrne, 1994). The unconstrained models allow all model parameters to be estimated freely for each group. The unconstrained measurement model (CFA) establishes whether configural invariance exists across groups (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). That is, in conducting a primary measure of invariance, it is first determined whether the factor structure is invariant, showing a consistent pattern of free and fixed factor loadings imposed on each construct including the direction and strength of factor loadings. In the constrained CFA model, cross-group equality constraints were placed on all factor loadings while covariances among factors were freely estimated for each group.6 In the constrained structural models, equality constraints were placed on all hypothesized paths between factors to examine whether there are significant differences in the magnitudes of path parameters across groups.7 For measurement and structural models, the equality constraints were made between the reference group (EA) and the other three groups.

Fit of all models was assessed by examining model χ2, the nonnormed fit index (NNFI), the comparative fit indices (CFI), and the root mean squared error approximation (RMSEA). NNFI and CFI values of greater than .90 indicate a good fit (Bentler, 1990). RMSEA values of less than .05 are considered evidence of a good fit, between .05 and .08 a fair fit, and greater than .10 a poor fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). The statistical significance of the estimated parameters was examined with z statistics at a .05 level of significance.

Several measures were used to evaluate the statistical significance of the difference between the unconstrained and the constrained models. The change in χ2 relative to the change in degrees of freedom is itself χ2 statistics, and indicates whether the constrained model has significantly worse fit than the unconstrained model (Byrne, 1994). However, this test is sensitive to large sample size and may lead to an overly conservative test of invariance (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Thus, following the example of Rosay, Gottfredson, Armstrong, and Harmon (2000), we examined the ratio of the change in χ2 to the change in degrees of freedom between the two models (Δχ2/Δdf). A value of 5 or above indicates a significant non-invariance (Rosay et al., 2000), and a change in CFI of greater than .01 indicates significant differences (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). The Lagrange multiplier (LM) test on the constrained models shows which equality constraints contribute most to degradation in model fit (Bentler, 1990).

Analysis strategy for missing data

Missing data occurred in all of the racial and ethnic groups, and the extent varied from group to group. The EA group showed the lowest rate of missing values in data points (7.03%), while the AA group had the highest rate (17.01%). The APIA (7.98%) and the multiracial (12.71%) groups fell in between. However, the patterns of missing data were similar across the groups. Some respondents did not finish the survey, some skipped questions, and/or some refused to answer questions. Although the percent missing on any given variable was low (<10%), listwise deletion would result in a large number of cases being dropped. Listwise deletion has also been shown to produce biased estimates and is discouraged unless the proportion of cases lost to missing data is small, e.g., 5% or fewer (Schafer & Graham, 2002).

Various techniques are available for dealing with missing data. Because each technique has strengths and limitations, a combination of these methods is recommended (Taylor, Graham, Cumsille, & Hansen, 2000). We utilized the expectation-maximization algorithm (EMCOV, Graham & Hofer, 1993), multiple imputations (NORM, Schafer & Olsen, 1997), and raw maximum likelihood (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Because the parameter estimates, significance tests, and χ2 estimates from each technique were quite similar, results are reported from analyses using an EMCOV generated covariance matrix that was entered into EQS 5.7b.

RESULTS

Measurement Model Testing

Testing the measurement model with each race and ethnic group

The measurement model included the nine latent factors specified by the partial SDM (Figure 1). The results of the CFAwith the EA group indicated that all factor loadings were significant and in the expected direction, as were all intercorrelations among the latent factors (range from −.63 to −.17 and .13 to .81), except the correlation between low SES and bonding to parents. The fit of the measurement model was good, with χ2(194) = 748.91, n = 644, NNFI of .91, CFI of .93 and RMSEA of .07. The results in other groups also showed that the fit of the measurement model was good.8 All factor loadings were significant within each group. The results are shown in Table 1 (factor loadings) and Tables 2 and 3 (factor intercorrelations).

TABLE 1.

Multiple Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Standardized Factor Loadings and z-Statistics

| Factors | Indicator | EA

|

AA

|

APIA

|

Multiracial

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loadings | z-Statistics | Loadings | z-Statistics | Loadings | z-Statistics | Loadings | z-Statistics | ||

| Low SES | SES1 | .80 | 9.75 | .52 | 5.36 | .76 | 10.25 | .86 | 9.71 |

| SES2 | .55 | 8.71 | .74 | 5.70 | .68 | 9.81 | .63 | 8.69 | |

| Poor parental monitoring | PPM1 | .67 | 11.55 | .67 | 10.16 | .73 | 9.56 | .77 | 13.16 |

| PPM2 | .37 | 8.08 | .41 | 7.60 | .39 | 7.03 | .48 | 9.33 | |

| Neighborhood safety | NS1 | .77 | 18.76 | .87 | 14.59 | .88 | 17.67 | .85 | 18.06 |

| NS2 | .85 | 20.50 | .74 | 13.18 | .87 | 19.07 | .82 | 17.46 | |

| Peer antisocial beliefs | PBL1 | .92 | 29.26 | .92 | 23.64 | .89 | 24.06 | .94 | 23.92 |

| PBL2 | .84 | 25.51 | .80 | 19.63 | .84 | 22.12 | .79 | 18.87 | |

| PBL3 | .75 | 21.88 | .72 | 16.62 | .78 | 20.07 | .70 | 16.34 | |

| Family socialization | FS1 | .75 | 20.71 | .73 | 17.09 | .78 | 19.35 | .80 | 18.79 |

| FS2 | .90 | 26.04 | .91 | 21.87 | .87 | 22.14 | .86 | 20.65 | |

| Bonding to parents | BP1 | .89 | 28.20 | .86 | 22.48 | .91 | 25.83 | .85 | 21.78 |

| BP2 | .85 | 26.11 | .82 | 20.88 | .91 | 25.92 | .86 | 21.88 | |

| BP3 | .87 | 27.48 | .80 | 20.28 | .87 | 23.87 | .86 | 21.85 | |

| Youth antisocial beliefs | YBL1 | .86 | 26.98 | .82 | 21.35 | .85 | 23.09 | .86 | 22.39 |

| YBL2 | .86 | 26.81 | .81 | 20.82 | .92 | 25.91 | .84 | 21.51 | |

| YBL3 | .89 | 28.06 | .91 | 24.93 | .86 | 23.66 | .91 | 24.40 | |

| Substance use | SUB1 | .77 | 22.28 | .75 | 18.12 | .69 | 17.33 | .83 | 20.81 |

| SUB2 | .78 | 22.54 | .76 | 18.50 | .93 | 26.40 | .86 | 22.10 | |

| SUB3 | .86 | 25.84 | .80 | 20.08 | .92 | 26.15 | .87 | 22.59 | |

| Violent behaviors | VIO1 | .77 | 21.95 | .71 | 16.60 | .74 | 18.20 | .83 | 20.39 |

| VIO2 | .67 | 17.98 | .69 | 16.11 | .63 | 14.71 | .74 | 17.27 | |

| VIO3 | .80 | 22.80 | .78 | 18.76 | .81 | 20.28 | .74 | 18.40 | |

SES, socioeconomic status; EA, European American; AA, African American; APIA, authoritative parenting among API.

TABLE 2.

Correlation Matrix, Means, and Standard Deviations for European and African American Samples

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Low SES | — | −.01 | .13 | .06 | −.13* | −.10 | .01 | −.01 | .09 |

| 2. Poor parent monitoring | .20* | — | .30* | .22* | −.57* | −.32* | .47* | .29* | .34* |

| 3. Lack of neighborhood safety | .16* | .44* | — | .16* | −.04 | .12 | .23* | .33* | .31* |

| 4. Peer antisocial beliefs | −.17* | .47* | .48* | — | −.09 | −.02 | .28 | .24* | .25* |

| 5. Family socialization | −.26* | −.63* | −.32* | −.25* | — | .68* | −.13* | .06 | −.04 |

| 6. Bonding to parents | −.07 | −.59* | −.22* | −.25* | .73* | — | −.06 | .04 | .04 |

| 7. Youth antisocial beliefs | .17* | .63* | .34* | .50* | −.37* | −.42* | — | .52* | .42* |

| 8. Substance use | .13* | .39* | .19* | .33* | −.20* | −.19* | .59* | — | .86* |

| 9. Violent behaviors | .22* | .46* | .41* | .42* | −.24* | −.23* | .59* | .81* | — |

| M | |||||||||

| European American | .07 | 1.89 | 1.47 | 1.37 | 2.82 | 2.62 | 2.54 | −.07 | −.15 |

| African American | .29 | 1.87 | 1.68 | 1.00 | 2.36 | 2.60 | 2.37 | .01 | .15 |

| SD | |||||||||

| European American | .21 | .83 | .54 | .59 | .80 | .74 | .60 | .76 | .64 |

| African American | .36 | 1.00 | .68 | .63 | .92 | .85 | .69 | .82 | .84 |

Note. European American sample results are below the diagonal and African American above the diagonal.

p<.05.

TABLE 3.

Correlation Matrix, Means, and Standard Deviations for Asian American and Multiracial Samples

| Factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Low SES | — | .08 | .29* | −.26* | −.13* | −.11* | .09 | .13* | .19* |

| 2. Poor parent monitoring | .24* | — | .15* | .18* | −.65* | −.56* | .50* | .34* | .43* |

| 3. Lack of neighborhood safety | .32* | .27* | — | .41* | −.20* | −.04 | .35* | .42* | .55* |

| 4. Peer antisocial beliefs | −.13* | .26* | .34* | — | −.20* | −.14* | .41* | .32* | .41* |

| 5. Family socialization | −.16* | −.56* | −.17* | −.22* | — | .76* | −.25* | −.12* | −.24* |

| 6. Bonding to parents | −.09 | −.30* | −.01 | −.20* | .75* | — | −.20* | −.06 | −.10 |

| 7. Youth antisocial beliefs | .05 | .35* | .33* | .43* | −.23* | −.10* | — | .67* | .65* |

| 8. Substance use | .00 | .09 | .26* | .27* | −.11* | −.04 | .42* | — | .83* |

| 9. Violent behaviors | .11 | .19* | .46* | .31* | −.13* | .03 | .55* | .80* | — |

| M | |||||||||

| Asian Pacific Islander American | .29 | 1.89 | 1.66 | 1.28 | 2.30 | 2.33 | 2.55 | −.12 | −.10 |

| Multiracial | .25 | 1.97 | 1.79 | 1.05 | 2.50 | 2.55 | 2.29 | .14 | .17 |

| SD | |||||||||

| Asian Pacific Islander American | .39 | 1.00 | .66 | .60 | .85 | .83 | .62 | .70 | .71 |

| Multiracial | .36 | 1.00 | .75 | .66 | .92 | .86 | .78 | 1.08 | .99 |

Note. Asian Pacific Islander American sample results are below the diagonal, and multiracial above the diagonal.

p<.05.

Testing the invariance of the measurement models across race and ethnic groups

A multiple group CFA was conducted to compare the factor loadings across the four groups. The fit of the unconstrained measurement model was good (χ2 (776) = 2335.29, NNFI of .92, CFI of .94 and RMSEA of .03). The constrained model also showed a good fit (χ2 (845) = 2768.26, NNFI of .91, CFI of .93 and RMSEA of .03). The difference between the unconstrained and constrained models was Δχ2 (69) = 432.97 (p<.05). The factor structure, including direction and significance of factor loadings was consistent across groups, indicating configural invariance. The change in CFI was equal to .01, but the ratio of the change in χ2 to the change of degree of freedom is 6.27, providing modest support for metric noninvariance. The multivariate LM test indicated that the largest difference between the EA group and the other three groups was in SES2, (χ2 = 22.00 with AA, χ2 = 47.06 with APIA, and χ2 = 51.28 with multiracial, p<.001). Two of the indicators of the outcome variables (SUB3 and VIO3) showed the second largest differences between EA and multiracial youth (χ2 = 32.50 for SUB3, χ2 = 30.57 for VIO3, p<.001). Although the ratio of χ2 between the unconstrained and the constrained models indicated some metric noninvariance, there was configural invariance for all factor loadings and metric invariance for the majority of factor loadings. Also, at least two factor loadings per factor were invariant across groups, the change in model fit indicated invariance, and the differences of magnitudes were relatively small. Therefore, we concluded that there was sufficient measurement invariance to permit testing of the structural model.

Structural Model Testing

Testing the structural model in each race and ethnic group

The structural model was first estimated with each group. The results (Figure 2) indicate that, among the EA group, all structural paths were significant as hypothesized, except the path from low SES to family socialization. The factor loadings of each indicator on its latent construct remained significant and in the expected direction. The model fit was good (Table 4). The amount of total variance of the outcome variable accounted for by the model was 36% for both outcomes. Low SES (β = .261), peer antisocial beliefs (β = .231), family socialization (β = −.133), and bonding to parents (β = −.179) had significant indirect effects (p<.05). In contrast, other factors (e.g., poor parental monitoring (β = .095), lack of neighborhood safety (β = .063)) were significantly associated with their immediate dependent variables, but did not explain the variance in the outcome variables. The model fit in other groups was good as well (Table 4). Combinations of significant and nonsignificant indirect effects were found in all racial and ethnic groups. A common pattern was evident: the indirect effect of low SES and peer antisocial beliefs was significant across all groups (ranged from .103 to .264 and .106 to .232, respectively). There were some differences in magnitude and significance of the associations between factors. These differences were explicitly examined in the subsequent multiple group analyses. Table 4 presents path coefficients for the theoretical model, organized by each racial and ethic group.

FIGURE 2.

Partial social development model with significant paths across groups.

TABLE 4.

Structural Mode: Standardized Path Coefficients and Model Fit

| Path | EA | AA | APIA | Multiracial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 644 | 478 | 491 | 442 |

| Low SES to poor parental monitoring | .70* | .44* | .49* | .28* |

| Low SES to lack of neighborhood safety | .70* | .39 | .66* | .65* |

| Low SES to peer antisocial beliefs | .68* | .24 | .52* | .64* |

| Low SES to family socialization | .05 | .23 | .06 | −.12 |

| Poor monitoring to family socialization | −.72* | −.67* | −.51* | −.65* |

| Family socialization to bonding to parents | .74* | .68* | .74* | .77* |

| Neighborhood safety to youth beliefs | .10* | .23* | .22* | .24* |

| Peer beliefs to youth beliefs | .39* | .24* | .36* | .30* |

| Bonding to parents to youth beliefs | −.30* | −.09 | −.04 | −.15* |

| Youth beliefs to substance use | .60* | .53* | .43* | .69* |

| Youth beliefs to violent behaviors | .60* | .43* | .56* | .67* |

| Fit indices of the model | ||||

| χ2 | 875.44 | 627.63 | 623.32 | 686.85 |

| Degree of freedom | 217 | 217 | 217 | 217 |

| NNFI | .91 | .90 | .93 | .91 |

| CFI | .92 | .92 | .94 | .92 |

| RMSEA | .07 | .06 | .06 | .07 |

| R2 in substance use | 36% | 28% | 18% | 47% |

| R2 in violent behaviors (%) | 36 | 18 | 32 | 45 |

EA, European American; AA, African American; APIA, Asian Pacific Islander American; NNFI, nonnormed fit index; CFI, comparative fit indices; RMSEA, root mean squared error approximation.

p<.05.

Testing the utility of the structural model across racial and ethnic groups

Comparisons of the structural model by racial and ethnic group were conducted using multiple-group SEM. The unconstrained model showed a good fit (with χ2(868) = 2813.24, N = 2,055, NNFI of .91, CFI of .92, and RMSEA of .03). The constrained structural model also showed a good fit (χ2(901) = 2952.88, N = 2,055, NNFI of .91, CFI of .92, and RMSEA of .03). The difference between the two models was Δχ2(33) = 139.64 (p<.05). While there were some differences in magnitude and significance of the associations among factors, both the unconstrained and the constrained models showed a good fit with the data; the change in CFI was 0 and the ratio of Δχ2 to Δdf was 4.23, indicating invariance of the theoretical model across groups.

The multivariate LM test indicated that there were some statistically significant differences in the coefficients for the following paths: youth antisocial beliefs to substance use for EAyouth versus those for multiracial youth (χ2 = 25.22, p< .001). This was also the case between EA and APIA (χ2 = 19.97, p<.001). So too, statistically significant differences were observed in the coefficients for youth antisocial beliefs to violent behaviors among EA versus multiracial youth (χ2 = 9.58, p<.05). This was also observed for the pathway, bonding with parents to youth antisocial beliefs, among EA and AA (χ2 = 11.51, p<.001) and APIA (χ2 = 12.81, p<.001), and low SES to poor parental monitoring between EA and multiracial youth (χ2 = 9.39, p<.05). The majority of the structural paths were of a similar magnitude and in the same direction across racial and ethnic groups. For example, the largest χ2 differences to the group differences in path equality constraints were between the standardized paths from youth antisocial beliefs to substance use for EA (β = −.60) and for multiracial youth (β = −.69).

Several differences between groups were also noted. The standardized coefficients for the path from bonding with parents to youth antisocial beliefs differed across groups. The path was nonsignificant among AA and APIA, while it was much weaker among multiracial youth than EA youth. These results did not support the study hypothesis that this relationship would be stronger among ethnic minority youth than EA youth. The findings also did not support the hypothesis predicting a weaker relationship between family socialization and bonding to parents among APIA and AA youth. This relationship was quite strong for all groups; it was only slightly lower for AA than for EA. In addition, EA had a stronger path between low SES and poor parental monitoring, but other relationships were of comparable magnitude, except that AA had nonsignificant relationships between low SES and peer antisocial beliefs and lack of neighborhood safety.

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of this study was to examine the applicability of the partial SDM to ethnic minority youth. SEM indicated that the partial SDM had a good model fit for all racial and ethnic groups, suggesting that the partial SDM could be utilized to explain substance use and violent behaviors across various racial and ethnic groups. Thus, despite the fact that EA youth share some mean differences in indicators with other racial and ethnic groups (Tables 2 and 3), the pattern of relationships among constructs is very similar across groups. This finding is consistent with some of the existing studies that show similarity in the basic processes and mechanisms leading to problem behaviors across different groups (e.g., Fleming, Catalano, Oxford, & Harachi, 2002; Griesler et al., 2002). However, there were group differences in magnitudes of some relationships. These comparisons helped illustrate similarities and differences between EA and other racial and ethnic groups in terms of the degrees of relationships among the model’s constructs.

The results demonstrated that several common risk factors for adolescent substance use and violent behaviors are identifiable across race and ethnic groups.

Youth beliefs were directly and significantly associated across all groups with substance use and violent behaviors. In addition, neighborhood environment and peer beliefs were significantly related across all groups to youth beliefs that lead to substance use and violent behaviors. Evidence in recent years has been inconclusive concerning the influence of neighborhood on adolescent behavior, with some studies indicating the presence of a significant effect (e.g., Duncan, Duncan, & Strycker, 2000; Griffin, Scheier, Botvin, Diaz, & Miller, 1999). Other research reports nonsignificance (e.g., Allison, Crawford, Leone, Trickett, Perez-Febles, Burton, et al., 1999; Bowen & Chapman, 1996). The findings of this study suggest that neighborhood context is indirectly but significantly associated with both substance use and violent behaviors among youth of different racial and ethnic groups. This is similar to the findings of indirect effect of neighborhood in a prior study (Brook et al., 1989). The findings of the present study also supported the hypothesis that a strong relationship exists between peer norms and youth beliefs across all racial and ethnic groups of youth.

In addition, the study found common processes of family socialization among racial and ethnic groups. Contrary to the study hypothesis, the relationships between family socialization and bonding to parents were significant in all groups. Specifically, youth who reported higher levels of family involvement and rewards from parents also reported higher levels of bonding to their parents regardless of their race and ethnicity. As prior studies show, relative to other groups, EA showed significantly higher levels of family socialization characterized by democratic parenting, communication, and rewards (Tables 2 and 3). However, the relationship between family socialization and bonding was not significantly different across groups. Similar patterns are found in other studies, e.g., between Chinese Americans and EA (Kim & Ge, 2000), and AA and EA (Huebner & Howell, 2003). It is possible that there is a universal process of family socialization (Middlemiss, 2003; Simons-Morton, 2002). However, more research is needed. Future investigations should employ comprehensive measures to further investigate this area; strong theoretical accounts suggest that family socialization processes and their impacts can be culture specific. Several empirical findings support these claims (discussed earlier).

The study also identified racial and ethnic differences in the degree of associations among some SDM constructs. Youth beliefs were more strongly related to substance use and violent behaviors among multiracial than EA youth. In addition, a nonsignificant association was found for the relationship between bonding to parents and youth beliefs among AA and APIA youth, and, while significant, the relationship for multiracial youth was half the size of the relationship for EA youth. This is curious because previous studies demonstrate the critical role of family relationship in youth development, and the protective effect of positive family relationship in preventing problem behaviors. In fact, the family relationship has a stronger effect on development among ethnic minority youth (Chan, 1992). The nonsignificant or weaker effect of bonding may be related to how we conceptualized such bonding. Bonding to parents in this study was operationalized as sharing feelings and thoughts with parents, wanting to be the kind of person as parents, feeling very close to parents, and enjoying spending time with parents. Other aspects of the close family relationship, though not included in this study, may be more relevant to APIA, AA, and multiracial youth (Chao, 1994). Such unmeasured aspects may in fact be strongly related to youth beliefs and behavior outcomes. For instance, a sense of obligation to family may be a critical indicator of family relationship among minority youth, which has been shown to be a protective factor for psychological and behavioral outcomes among minority youth (Fuligni, Yip, & Tseng, 2002).

Much stronger associations between low SES and parental monitoring were found among EA youth than among other groups. Among AA, there were nonsignificant relationships between low SES and lack of neighborhood safety, and between low SES and peer beliefs. One may suspect more heterogeneity in SES among EA in the sample than among the other groups. Although a higher proportion of AA were from lower SES families in our sample, the factor variances were actually smaller for EA than for other groups: .11 for EA, .28 for AA, .52 for APIA, and .52 for multiracial youth. Therefore, the lack of variance is ruled out as a possible reason for these differences. Alternatively, low SES may have more impact on parental monitoring for EA and less impact on neighborhood and peer groups for AA. McLeod and Nonnemaker (2000) report the differential effects of low-income status between majority and minority youth. This includes a stronger effect of low SES for EA. Although we hypothesized that the effects of SES would be equal across groups, there may be variations in how low-income status influences parental strategies and child development. Further investigation is warranted to more precisely understand these group differences. Future efforts should take into account the contextual and structural variations across groups, as well as within-group differences.

This study is not without limitations. First, because it utilized cross-sectional data, causal claims about the direction of associations cannot be made. This is of particular concern in determining the causal direction among family constructs including parental monitoring, family socialization, and bonding to parents. While the SDM hypothesizes that these processes are conceptually and causally distinct, a stronger test of these hypotheses requires longitudinal data. While data were based on youth self-reports, such reports have generally been found to be reliable and valid for many variables (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2001). It should also be noted that not all SDM constructs and pathways were included in the model test because of the limited measurement. These missing constructs may have important implications for the mediation of external constraints, including neighborhood safety and peer beliefs, in that mediation may be through both omitted and included constructs. The SDM posits that bonding serves as protection against problem behaviors only when the adolescent is bonded to socializing units in which norms disapprove of such behaviors (i.e. prosocial socialization). This partial test of the SDM is not able to distinguish between the prosocial and antisocial norms promoted by parents. Family socialization was tested as a combined construct of family involvement and rewards in this study, but it is advantageous both conceptually and from a prevention standpoint to distinguish the effects of the distinct constructs involved in this process. Another limitation of the study is that APIA youth were aggregated as one group, despite their diversity. The issue of within-group diversity also applies to multiracial groups. Lastly, the respondents of the study were mainly from one geographical location, thus, caution is advised in generalizing the findings.

Implications for Prevention

The development of interventions to prevent or reduce problem behaviors among adolescents is significantly informed by a thorough understanding of theory and the applicability of theory across racial and ethnic groups. This study is an attempt to fill a gap in prevention research by explicitly examining similarities and differences of a partial test of the SDM across different racial and ethnic groups. While further research is needed to translate the findings into intervention programs, this study has some implications for the development of interventions for ethnic minority youth. First, this study demonstrates that there are several common predictors of substance use and violent behaviors for adolescents, regardless of their race and ethnicity. For example, youth beliefs, neighborhood safety, and peer beliefs were associated with problem behaviors, directly or indirectly, across all groups. This implies that preventive interventions should include these factors when targeting EA, AA, APIA, and multi-racial youth. At the same time, the findings also demonstrate that there are racial and ethnic group differences in the magnitudes of relationships among theoretical constructs. For example, youth beliefs were more strongly related to problem behaviors among multiracial youth than EA youth. Bonding to parents is also differently associated with youth beliefs among ethnic minority youth. Further study is warranted to develop better understanding of the differential magnitudes of factors that influence problem behaviors among racial and ethnic subgroups, so that the emphases in preventive interventions can be appropriately placed. Given the dramatic increase in ethnic minority populations, expansion of such etiological comparisons is critical.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by a dissertation grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH62884) to the first author and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Minority Programs (HD30097). An earlier version of this article was presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Prevention Research in Washington, DC, June 2001.

Footnotes

The hypotheses developed for this study are only concerned with the comparisons between EAyouth and other groups. In other words, we did not develop hypotheses regarding the possible differences among APIA, AA, and multiracial youth. We made this decision in part because the main purpose of the study is to explicitly test across ethnic minority groups the utility of the model that has been tested only with samples undifferentiated by racial and ethnic groups, rather than to investigate differences among ethnic minority groups.

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine whether the experimental and control groups could be combined. The equivalence of the covariance structures of the intervention and control groups was determined using multiple group comparisons (Byrne, 1994). The fit of the unconstrained model was χ2 (348) = 1157.51, comparative fit indices (CFI) = .97, root mean squared error approximation (RMSEA) = .03, and for the constrained model it was χ2 (384) = 1228.74, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .03. The fit indices indicated good fit for both models. The coefficients for the parameters were all statistically significant and their magnitudes were also almost identical. The ratio of the difference in χ2 between the unconstrained and the constrained models to the difference in degrees of freedom between the two models (Δχ2/Δdf) was 1.98, which is less than 5. In addition, the change in CFI was zero. There was no difference in the means of the outcome variables across the two groups. Thus, the intervention and control groups were combined for the subsequent analyses.

Items were parceled to create indicators. Parceling involves combining several items into one indicator by averaging or summing the items (Kishton & Widaman, 1994). There are two methods of parceling: (1) items in each parcel indicate a single domain of the construct, or (2) parcels represent the multiple aspects of a construct, thus necessarily not a single sub-domain of the construct (Kishton & Widaman, 1994). It is reported that each method has its unique sphere of application (Kishton & Widaman, 1994). This study takes the second approach in parceling because (1) the main focus of the study is to examine the structural model but not the multiple sub-domains of the constructs, and (2) parceling with the second approach helps reduce the number of parameters to be estimated, thus requiring smaller samples to test the model.

The items inquired about the frequency of common substances (e.g., cigarettes and alcohol) within the month prior to survey. Other items inquired about use of substances less commonly and less frequently (e.g., crack or cocaine) within much longer time frames. The same was applied to violent behaviors. Although the time frames were different, each item measured degrees of each behavior. There was no case of double counting in any of the indicators because each behavior was measured only once. The response options were standardized and the latent constructs indicated the degrees of substance use and violent behaviors.

It is usually the case that Latino ethnicity is crossed with race. For example, EA, AA, or APIA can be all Latino. In this study, Latino/Hispanic is regarded as a separate racial and ethnic category. Those who marked only one group are classified as monoracial (and further classified as EA, AA, APIA, Latin-, and Native Americans). Those who marked more than one group are classified as multiracial. Thus, if one marked both Black/African American and Latino/Hispanic, the individual was classified as multiracial.

Complete factorial invariance is obtained if there are identical corresponding factor loadings, factor variances and covariances, error variances and covariances across groups (Hancock, Stapleton, & Berkovits, 1999). However, the equality of error variances and covariances tend to be the least important hypotheses to test (Byrne, 1994). With few exceptions (e.g., growth hypotheses), researchers use less restrictive invariance criteria in which only the corresponding factor loadings are equivalent across groups (i.e., metric invariance) (Byrne, Shavelson, & Muthen, 1989). Thus, tests of invariance usually begin with a test of the equality of factor loadings across groups (Byrne, 1994). Some argue that even metric invariance is too rigid and unrealistic for cross-group analysis (Hancock et al., 1999; Horn & McArdle, 1992).

There is inconsistency in how researchers handle invariance of measurement in testing structural models across groups (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Consensus indicates that configural invariance should be established to proceed to further restrictive testing. However, opinions vary on how to handle metric invariance (Horn & McArdle, 1992; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Hancock et al. (1999) recommend that when the focus of research is on the latent structural relations, researchers should minimize the use of constraints, because improper constraints can impair the accuracy of structural invariance tests by compromising the integrity of the group’s inter-factor covariances and by introducing badness of fit. Bollen (1989) recommends testing the paths before testing metric invariance when the main focus of the investigation is to see the differences of path coefficients. Several studies follow this guideline (e.g., Fleming et al., 2002; Kim & Ge, 2000). Based on the guidelines and published examples, equality constraints were not placed on factor loadings in this study. In addition, measurement invariance testing further justified our decision.

The measurement model fit was for AA χ2 (194) = 515.88, n = 478, NNFI of .92, CFI of .93 and RMSEA of .06; for APIA χ2 (194) = 518.70, n = 491, NNFI of .94, CFI of .95 and RMSEA of .06; and for multiracial χ2 (194) = 551.93, n = 442, NNFI of .92, CFI of .94 and RMSEA of .07.

Contributor Information

Yoonsun Choi, University of Chicago.

Tracy W. Harachi, University of Washington

Mary Rogers Gillmore, University of Washington.

Richard F. Catalano, University of Washington

References

- Akers RL, Krohn M, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M. Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:636–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison KW, Crawford I, Leone PE, Trickett E, Perez-Febles A, Burton LM, et al. Adolescent substance use: Preliminary examinations of school and neighborhood context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:111–141. doi: 10.1023/A:1022879500217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Fit indexes, Lagrange multipliers, constraint changes and incomplete data in structural models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:163–172. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS structural equations program manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Software; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen GL, Chapman MV. Poverty, neighborhood danger, social support, and the individual adaptation among at-risk youth in urban areas. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:641–666. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Nomura C, Cohen P. A network of influences on adolescent drug involvement: Neighborhood, school, peer, and family. Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs. 1989;115:125–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthen B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105:456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social developmental model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Krenz C, Gillmore M, Morrison D, Wells E, et al. Using research to guide culturally appropriate drug abuse prevention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:804–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Newcomb MD, Abbott RD. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance abuse: A test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:429–455. doi: 10.1177/002204269602600207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Gillmore MR, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Ethnic differences in family factors related to early drug initiation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53:208–217. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Oxford ML, Harachi TW, Abbott RD, Haggerty KP. A test of the social development model to predict problem behaviour during the elementary school period. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1999;9:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2000;49:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Families with Asian roots. In: Lynch EW, Hanson MJ, editors. Developing cross-cultural competence: A guide for working with young children and their families. Baltimore, MD: Paul. H. Brookes; 1992. pp. 181–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chao R. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65:1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD. Social control and social learning models of delinquent behavior. Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 1976;14:17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney TM, Radina ME. Adjustment problems in adolescence: Are multiracial children at risk? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:433–444. doi: 10.1037/h0087744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckart K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Physical discipline among African American and European-American mothers: Links to children’s externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Dryfoos JG. Safe passage: Making it through adolescence in a risky society: What parents, schools, and communities can do. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. Risk and protective factors influencing adolescent problem behavior: A multivariate latent growth curve analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;22:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF02895772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, Catalano RF, Oxford ML, Harachi TW. A test of generalizability of the Social Development Model across gender and income groups with longitudinal data from the elementary school developmental period. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18:423–439. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Yip T, Tseng V. The impact of family obligation on the daily activities and psychological well-being of Chinese American adolescents. Child Development. 2002;73:302–314. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson DC, Koper CS. Race and sex differences in the prediction of drug use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:305–313. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Hofer SM. EMCOV.exe users guide. University Park, PA: Department of Biobehavioral Health, Pennsylvania State University; 1993. (Unpublished Manuscript) [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT. Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment theory and research. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 469–496. [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB, Davies M. Ethnic differences in predictors of initiation and persistence of adolescent cigarette smoking in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2002;4:79–93. doi: 10.1080/14622200110103197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Diaz T, Miller N. Interpersonal aggression in urban minority youth: Mediators of perceived neighborhood, peer, and parental influences. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Eccles JS. Financial strain, parenting behaviors, and adolescents’ achievement: Testing model equivalence between African American and European American single- and two-parent families. Child Development. 1999;70:1464–1476. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock GR, Stapleton LM, Berkovits I. Loading and intercept invariance within multisample covariance and mean structure models. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association; Montreal, Canada. 1999. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Weis JG. The social development model: An integrated approach to delinquency prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention. 1985;6:73–97. doi: 10.1007/BF01325432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Herman-Stahl MA. Neighborhood safety and social involvement: Associations with parenting behaviors and depressive symptoms among African American and Euro-American mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:209–219. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL, McArdle JJ. A practical and theoretical guide to measurement invariance in aging research. Experimental Aging Research. 1992;18:117–144. doi: 10.1080/03610739208253916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell JC, Krisberg B, Hawkins JD, Wilson JJ, editors. A sourcebook: Serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, White HR, Kosterman R, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. Developmental associations between alcohol and interpersonal aggression during adolescence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2001;38:64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner A, Howell LW. Examining the relationship between adolescent sexual risk-taking and perceptions of monitoring, communication, and parenting styles. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:71–78. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Jakob-Chien C. The contemporaneous co-occurrence of serious and violent juvenile offending and other problem behaviors. In: Loeber R, Farrington D, editors. Serious and violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. NIH Publication No. 00-4923. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2001. The monitoring the future national survey results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitçibasi Ç. Family and human development across cultures. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Ge X. Parenting practices and adolescent depressive symptoms in Chinese American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:420–435. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Widaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar A, Buehler C, Barber B. Youth perceptions of interpersonal conflict, ineffective parenting, and youth problem behaviors in European-American and African-American families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2003;20:239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lonczak HS, Huang B, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD, et al. The social predictors of adolescent alcohol misuse: A test of the Social Development Model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:179–189. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguin E, Loeber R. Academic performance and delinquency. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and justice: An annual review of research. Vol. 20. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. pp. 145–264. [Google Scholar]

- Matsueda RL. Testing control theory and differential association: A causal modeling approach. American Sociological Review. 1982;47:489–504. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy MG, Frick PJ, Loney BR, Ellis ML. The potential mediating role of parenting practices in the development of conduct problems in clinic-referred sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1999;8:477–494. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod JD, Nonnemaker JM. Poverty and child emotional and behavioral problems: Racial/ethnic differences in processes and effects. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:137–161. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of coloar: A decade review of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Middlemiss W. Brief report: Poverty, stress, and support: Patterns of parenting behaviour among lower income Black and low income White mothers. Infant and Child Development. 2003;12:293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry RS, Vandewater EA, Huston AC, McLoyd VC. Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development. 2002;73:935–951. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Muuss R. Theories of adolescence. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council Panel on High-Risk Youth. Losing generations: Adolescents in high risk settings. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]