Abstract

Macrophages activated through Toll receptor triggering increase the expression of the A2A and A2B adenosine receptors. In this study, we show that adenosine receptor activation enhances LPS-induced pfkfb3 expression, resulting in an increase of the key glycolytic allosteric regulator fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and the glycolytic flux. Using shRNA and differential expression of A2A and A2B receptors, we demonstrate that the A2A receptor mediates, in part, the induction of pfkfb3 by LPS, whereas the A2B receptor, with lower adenosine affinity, cooperates when high adenosine levels are present. pfkfb3 promoter sequence deletion analysis, site-directed mutagenesis, and inhibition by shRNAs demonstrated that HIF1α is a key transcription factor driving pfkfb3 expression following macrophage activation by LPS, whereas synergic induction of pfkfb3 expression observed with the A2 receptor agonists seems to depend on Sp1 activity. Furthermore, levels of phospho-AMP kinase also increase, arguing for increased PFKFB3 activity by phosphorylation in long term LPS-activated macrophages. Taken together, our results show that, in macrophages, endogenously generated adenosine cooperates with bacterial components to increase PFKFB3 isozyme activity, resulting in greater fructose 2,6-bisphosphate accumulation. This process enhances the glycolytic flux and favors ATP generation helping to develop and maintain the long term defensive and reparative functions of the macrophages.

Keywords: Gene Expression, Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Macrophage, Phosphofructokinase, Toll-like Receptors, Adenosine Receptor

Introduction

Macrophages are key cellular components of the innate immune system. They are present in all body tissues, where they normally assist in guarding against invading pathogens, and regulate normal cell turnover and tissue remodeling. Macrophages discriminate between pathogens and self through signals triggered by Toll-like receptors, which recognize different pathogen components, such as LPS, lipoproteins, or dsRNA, among others (1). Activation of most Toll receptors triggers a complex signaling pathway involving the transcription factor NFκB (2), which, upon activation, induces the expression of multiple genes implicated in the inflammatory response, including cytokines, effector enzymes such as iNOS and COX-2, and adhesion molecules that enable macrophages to mount an immediate attack against pathogens (1).

The activation of macrophages is dependent on various energy-requiring pathways, mainly glycolysis (3). To reach the inflammation sites, macrophages recruited from the blood need to move against oxygen gradients (4). Macrophages and other cells of the innate immune system need to adapt to this special condition to maintain viability and activity. Therefore, a high glycolytic flux is essential for macrophage activity in these conditions (5, 6).

Unlike almost all other cells, macrophages and myeloid cells do not typically shift to mitochondrial respiration, even in highly oxygenated environments. Indeed, glycolytic inhibitors have been shown to greatly reduce both the cellular ATP concentration and the functional activity of macrophages, whereas inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration have shown no effect on the inflammatory response (5, 7, 8). Macrophages activated by LPS increase the levels of lactate production (5), a marker of enhanced glycolytic function. Glycolytic flux is mainly controlled by 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase (9), with fructose 2,6-bisphosphate (Fru-2,6-P2)2 being its most powerful allosteric activator. This property confers to this metabolite a key role in the control of the glycolytic pathway (10). 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFK-2) is the bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis and degradation of Fru-2,6-P2 and, hence, critically regulates the glycolytic rate under multiple pathophysiological conditions (10). Different PFK-2 isozymes generated from four genes (pfkfb1–4) have been identified in mammalian tissues (11). Proliferative and transformed cells and macrophages express the PFKFB3 isozyme, which is a product of the pfkfb3 gene (12–16). This isoform presents the highest kinase-bisphosphatase activity ratio, thus generating the highest Fru-2,6-P2 levels. PFKFB3 isozyme expression is induced by proinflammatory stimuli, hypoxia, and growth factors in different cells (12, 17), and the protein is degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway (18). pfkfb3 mRNA contains multiple copies of the AUUUA instability motif in its 3′-nontranslated region (14). This sequence motif confers both enhanced translation and instability to the mRNA molecule, and thus it plays an important role in regulating the half-life of the gene product in different physiological conditions. Analysis of the 5′ pfkfb3 promoter sequence has revealed the presence of putative consensus binding sites for different transcription factors, which could play important roles in the regulation of pfkfb3 gene expression. Binding of the transcription factor HIF1 seems critical for the hypoxia-dependent induction of this gene (17).

Although macrophage function is essential for the successful destruction of pathogens, failure to control macrophage activation or prolonged or inappropriate inflammatory processes will lead to unacceptable levels of collateral damage to surrounding cells. Multiple mechanisms controlling the extension of macrophage activation have been described (19). In the last years, adenosine has been shown to modulate the inflammatory response by limiting macrophage activation (20, 21). Utilization of ATP during periods of high metabolic activity leads to an increased concentration of intracellular adenosine that can be secreted through nucleoside transporters. Another major pathway contributing to high extracellular adenosine concentration during metabolic stress is the release from the cells of its precursor adenine nucleotides (ATP, ADP, and AMP), followed by extracellular degradation to adenosine. Adenosine accumulation is limited by its catabolic degradation to inosine and uric acid (20). Neutrophils and endothelial cells release large amounts of adenosine at sites of inflammation and infection. Activated macrophages can also serve as a major source of extracellular adenosine via ATP production (22). Adenosine acts at the cell surface through four G protein-coupled adenosine receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3). Lower concentrations of adenosine activate the high affinity A1 and A2A receptors, whereas a high adenosine concentration also stimulates the low affinity A2B and A3 receptors (20). Adenosine receptors expressed on monocytes and macrophages allow these cells to detect stressful conditions and modulate their cellular functions to adapt to their microenvironment. Activation of A2A receptors in macrophages has been related to the anti-inflammatory effects of adenosine, such as the down-regulation of TNFα production (20, 23), and to a macrophage-regenerative phenotype, as suggested by the production of VEGF (24, 25). The use of A2A receptor-deficient mice as a model of acute inflammation has demonstrated clearly the role of these receptors in immunosuppression (26–28).

In this study, we show that Toll receptor agonists and adenosine, through its A2A and A2B receptors, cooperate to increase glycolytic flux in macrophages by favoring the expression of the PFKFB3 isozyme. We have found that the Toll-4 receptor agonist LPS increases the expression of A2A and A2B receptors in macrophages, augmenting its sensibility to adenosine. We also show here that although LPS-dependent induction of HIF1α is essential for pfkfb3 expression, the synergic induction of pfkfb3 expression observed with A2R agonists critically depends on the transcription factor Sp1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Adenosine, A2A receptor agonist 2-p-(2-carboxyethyl) phenethylamino-5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (CGS-21680), A2 receptor agonist 5′-(N-ethylcarboxamido)adenosine (NECA), A2B receptor antagonist 8-[4-[4-cyanophenyl)carbamoylmethyl)oxy]phenyl]-1,3-di(n-propyl)xanthine (MRS 1754), deferoxamine, and CoCl2 were purchased from Sigma. A2A receptor antagonist 4-(2-triazolo(2,3-α)triazin-ylamino)ethyl)phenol (ZM 241385) was purchased from Tocris Cookson. Toll receptors agonists, LPS from Salmonella typhimurium, poly(I:C), LTA-SA, and CpG were from Sigma. Serum and culture medium were acquired from BioWhittaker (Walkersville, MD). Electrophoresis equipment and reagents were purchased from Bio-Rad.

Cell Culture

Elicited peritoneal macrophages were obtained from male mice 4 days after intraperitoneal inoculation of 1 ml of sterile 10% (w/v) thioglycollate. Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105/cm2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS and 50 μg/ml each gentamicin, penicillin, and streptomycin. Raw 264.7 cells were subcultured at a density of 6–8 × 104/cm2 in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mm glutamine, 10% FCS, and the aforementioned antibiotics. After 2 days in culture, the medium was replaced by RPMI 1640 containing 5% FCS, and the cells were used in the following 24 h. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were obtained by flushing the femurs from IRF-3+/+ or IRF-3−/− mice with DMEM containing 10% inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Sigma) and subsequent culture in the same medium supplemented with 15% of L929 supernatant as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

Stable cell lines expressing dominant active forms of IκBα (Raw-IκB-DA) have been described elsewhere (29). Human monocytes were isolated from the blood of healthy donors by centrifugation on Ficoll-PaqueTM PLUS (Amersham Biosciences) following previously reported protocols (30). Hypoxia simulation conditions were achieved by growing cells in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 200 μm deferoxamine or 200 μm CoCl2.

Metabolite Determinations

Fru-2,6-P2 was determined as described previously (31). The concentration of lactate was measured enzymatically in neutralized HClO4 extracts, as described previously (32). Biochemicals used for these measurements were from Roche Applied Science. ATP levels were determined by following the Sigma ATP bioluminescent somatic cells assay kit.

Generation of Plasmids and Mutant Constructs

Plasmids pCMV-SPORT6-A2AR and pCMV-SPORT6-A2BR were purchased from ATCC. shRNA plasmid for mouse A2AR and A2BR and shRNA plasmid for mouse HIF1α and C/EBPβ and -δ were purchased from SABiosciences; Sp1 siRNAs were from Ambion. p-GL2-basic luciferase expression vectors containing various lengths of 5′-flanking regions from the human pfkfb3 gene promoter and an HIF1-luciferase reporter gene have been described previously (17, 33).

Mutated pfkfb3 gene promoter constructs were prepared by gene synthesis following instructions included in the QuikChange (Stratagene) site-directed mutagenesis kit. Forward oligonucleotides used in binding site mutations (represented in boldface type) were as follows: SP1 (−110 CCC ACG TGG AAG GGT ATT GGG ACC CAA GGA ATG CG−75 and −83 ATG CGG CCC GTA TCG AGG CTG ACG TAG CGT C−48); HIF (−121 CCA CCC TCC TCC CCT GGT GGA AGG GGG CTG G−90); cEBP (−872 CCC TCG ACT TAG GCT GTG AAT TGC AGA TCG AAA TGG G−835). Mutated sites were confirmed by DNA sequencing. All plasmid DNA was purified using EndoFree columns (Qiagen).

Cell Transfections

Subconfluent Raw 264.7 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and transfected on the following day with 600 ng of plasmid DNA by using the FuGENE 6 reagent (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. A β-galactosidase expression vector was used as an internal control for transfection efficiency. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured by using a commercial kit (Promega). To evaluate shRNA efficiency, Raw cells were cotransfected with GFP, and GFP+ cells were analyzed by Western blot.

RNA Extraction and Analysis of Gene Expression by Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted (from 2 to 4 × 106 cells) by following the Qiagen RNA purification method. For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA by using the RevertAidTM HMinus First Strand (Fermentas) cDNA synthesis kit. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed following the SYBR Green protocol from Applied Biosystems. Amplification of the housekeeping gene GADPH was used as a quality and loading control. The forward and reverse primers, respectively, used for quantitative PCR amplification were as follows: GADPH, 5′-AAC TTT GGC ATT GTG GAA GG-3′ and 5′-GGA TGC AGG GAT GAT GTT CT-3′; A1R, 5′-TTC TGC GTC CTG GTA TGT GAC CAA-3′ and 5′-GCA GAG CCC AGC TTT GGA AAT TGA-3′; A2AR, 5′-ACA CGC CTC AGC AAG ACA CAA T-3′ and 5′-AAA GCC AGC GTT GTG CAT CT-3′; A2BR, 5′-ATT CGC GTC CCG CTC AGG TAT AAA-3′ and 5′-AAT CCA ATG CCA AAG GCA AGG ACC-3′; A3R, 5′-ACG CGA ACT CCA TGA TGA ACC CTA-3′ and 5′-ACT GAT ACC ACA TGC GAA GGC AGA-3′; HIF1α, 5′-CTA CTG CAG GGT GAA GAA TTA CTC AGA GC-3′ and 5′-GTG CAA TTG TGG CTA CCA TGT ACT GCT G-3′; PFKFB3, 5′-TCT AGA GGA GGT GAG ATC AG-3′ and 5′-CCT GCC ACT CTT ATC TTC TG-3′; iNOS, 5′-GCA AGT CCA AGT CTT GCT TGG-3′ and 5′-GGT TGA TGA ACT CAA TGG CAT CAT G-3′; TNFα, 5′-GAC GTG GAA CTG GCA GAA GAG-3′ and 5′-AAG CAG GAA TGA GAA GAG GCT G-3′; GLUT1, 5′-GGG CAT GTG CTT CCA GTA TGT-3′ and 5′-ACG AGG AGC ACC GTG AAG AT3′; phosphoglycerate kinase, 5′-CTG TGG TAC TGA GAG CAG CAA GA-3′ and 5′-CAG GAC CAT TCC AAA CAA TCT G-3′; and VEGF, 5′-AGT CCC ATG AAG TGA TCA AGT TCA-3′ and 5′-ATC CGC ATG ATC TGC ATG G-3′.

Preparation of Cell Extracts and Western Blot Analysis

Adherent macrophages (1–3 × 106 cells) were washed twice with ice-cold PBS, scraped off the dishes, and collected by centrifugation. Cell pellets were homogenized with 200 μl of lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 0.4 m NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 0.5 mm EGTA, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, 10 μm leupeptin, 10 mm sodium fluoride, 1 mm sodium vanadate, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40). Cells were gently vortexed for 20 min at 4 °C, and following centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 15 min, the supernatants were stored at −80 °C (total extracts). Sample protein concentrations were determined by using the detergent-compatible protein reagent from Bio-Rad. Samples containing equal amounts of protein were boiled in denaturing buffer (250 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 2% β-mercaptoethanol) and size-separated by loading 80–120 μg of total cell extracts per well in a polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 10% SDS. The gels were transferred to HybondTM-C extra nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences), which were then processed according to the recommendations provided by the antibody suppliers.

An antibody against PFKFB3 was obtained as described previously (16). Anti-HIF1α antibody was purchased from R&D Systems. Anti-phospho-AMPK-α-Thr-172 or anti-AMPK-α antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling. α-Tubulin was detected using anti-α-tubulin antibody purchased from Sigma. Anti-C/EBPβ, anti-C/EBPδ, anti-Sp1, anti-Ser(P), anti-A2AR, and anti-A2BR antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Proteins were detected by ECL (Amersham Biosciences). In each assay, several film exposure times were used to avoid film saturation.

Data Analysis

The number of experiments performed and analyzed is indicated in the corresponding figure legends. Statistical differences (p < 0.05) between mean values were determined by one-way analysis of the variance, followed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

Toll Receptor Agonists Increase pfkfb3 Gene Expression in Macrophages

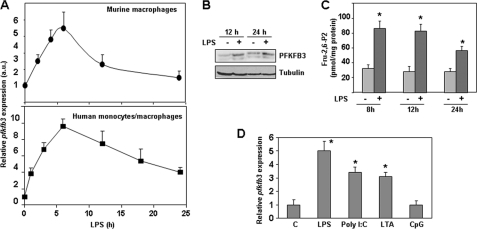

Macrophage activation with LPS increased the expression of pfkfb3 in both murine peritoneal macrophages and human monocytes/macrophages (Fig. 1A). Maximal mRNA levels were reached about 6 h after LPS triggering and decreased to near control levels 24 h after stimulation. These results agree with previous observations in human monocytes (14). Increased PFKFB3 isozyme levels could be detected for at least 24 h (Fig. 1B), and in accordance with that, elevated levels of the metabolite Fru-2,6-P2 were detected 8 h after macrophage activation by LPS and could be observed for 24 h (Fig. 1C). We have extended these initial studies and confirmed that, besides LPS, other Toll receptor agonists, such as viral double-stranded RNA and bacterial lipopeptides, also increase pfkfb3 gene expression (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that up-regulation of pfkfb3 is a common process in the course of macrophage activation.

FIGURE 1.

Toll receptor agonists increase pfkfb3 gene expression in macrophages. A, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of pfkfb3 mRNA levels in peritoneal murine macrophages and human monocytes/macrophages activated for different times with the TLR4 agonist LPS (100 ng/ml). B, Western blot analysis of PFKFB3 protein. C, Fru-2,6-P2 levels in peritoneal macrophages activated for different times with LPS. D, expression of pfkfb3 mRNA analyzed by RT-PCR after triggering macrophages with TLR3 (poly(I:C) 200 ng/ml), TLR2 (LTA-SA 2 μg/ml), or TLR9 (CpG 500 ng/ml) agonists for 6 h. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control cells (A, C, and D) or correspond to a representative experiment out of three (B). a.u., arbitrary units.

Adenosine Cooperates with LPS to Increase pfkfb3 Gene Expression

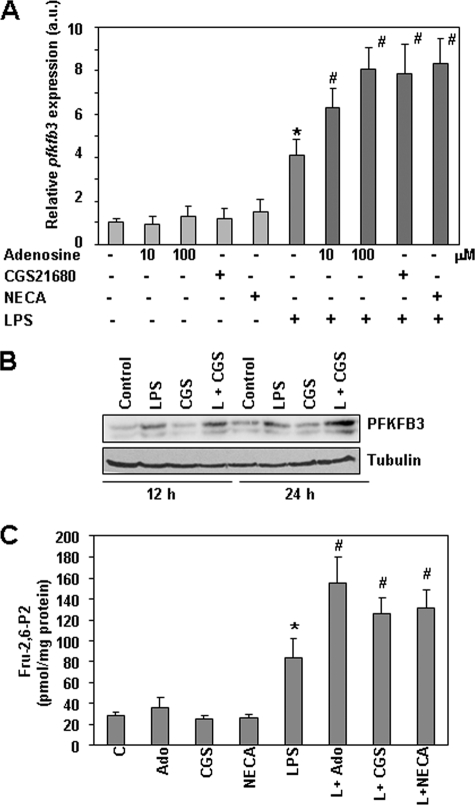

As macrophage activation by pathogens increases ATP consumption (34), and high metabolic activity leads to the liberation of adenosine (35), we explored whether adenosine could affect pfkfb3 expression and thus modulate the glycolytic flux in activated macrophages. Adenosine, the A2AR-specific agonist CGS1680, or the A2R-nonspecific agonist NECA exerted little effect by themselves in resting macrophages, but they all cooperated with LPS to increase pfkfb3 expression (Fig. 2, A and B). Increased levels of the metabolite Fru-2,6-P2 were found also in macrophages treated with LPS and adenosine or A2 receptor agonists (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Adenosine receptor agonists modulate LPS-induced pfkfb3 gene expression in macrophages. A, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of pfkfb3 mRNA expression in peritoneal macrophages treated for 6 h with LPS (100 ng/ml), adenosine (10 or 100 μm), the specific A2 receptor agonist CGS21680 (2 μm), or the nonselective A2 receptor agonist NECA (10 μm). B, analysis of PFKFB3 expression by Western blot performed with extracts from peritoneal macrophages treated for 12 or 24 h with the same concentrations as above of the indicated agents. A representative experiment is shown. C, Fru-2,6-P2 levels in macrophages treated for 12 h as in A. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control cells. #, p < 0.05 versus LPS-treated cells. a.u., arbitrary units.

In the few last years, adenosine has been shown to modulate the inflammatory response by limiting macrophage activation through the A2A receptors and to favor the development of an angiogenic phenotype (20, 21). To assess whether adenosine and the other A2R agonists worked correctly in our cells, we evaluated their effects on TNFα, VEGF, and iNOS expression after induction with LPS. In agreement with previous reports (25, 36), TNFα expression was repressed in macrophages treated with adenosine or CGS1680, whereas LPS-induced iNOS and VEGF expression was increased (supplemental Fig. 1). Therefore, taken together, these results identify, for the first time, pfkfb3 as a gene whose expression is synergistically up-regulated by LPS and adenosine, leading also to a synergistic effect on Fru-2,6-P2 production.

Toll-4 Signaling Increases the Expression of A2A and A2B Receptors

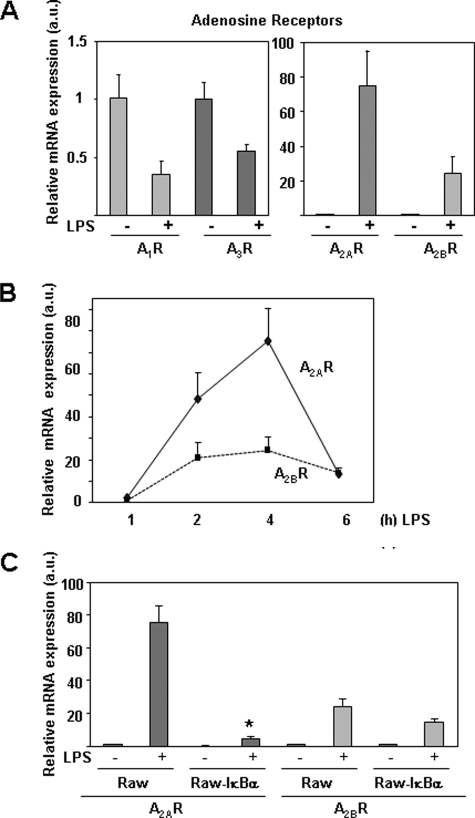

A previous report has shown that adenosine receptors are modulated by LPS (37). We also report here a potent increase in the expression of A2A and A2B receptors in murine macrophages activated with LPS (Fig. 3A). The mRNA levels of A1 and A3 adenosine receptors decreased in this condition (Fig. 3A), as described previously (37). Although the induction relative to basal levels of A2BR by LPS was lower than that observed for A2AR (Fig. 3, A and B), basal expression levels of A2BR in control macrophages were higher than the levels of A2AR (data not shown). Both A2A and A2B receptors were induced transiently and rapidly by LPS, reaching maximal mRNA levels 4 h after treatment and diminishing to basal levels in a short period of time (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

LPS increases the expression of A2 receptors in macrophages. A, RT-PCR analysis of the four adenosine receptors in peritoneal macrophages treated with LPS (100 ng/ml) for 4 h. B, time course of A2A and A2B receptor expression in macrophages treated with LPS for the indicated times. C, analysis by quantitative RT-PCR of A2A and A2B receptor expression in control or Raw 264.7 cells expressing the super-repressor protein IκBα (Raw-IκBα-SR), 4 h after treatment with LPS. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. a.u., arbitrary units.

We have also observed that A2A receptor induction by LPS is highly dependent on NFκB activation, as Raw-IκBα-SR cells, which overexpress the super-repressor IκBα (unable to undergo phosphorylation and degradation and therefore maintaining low levels of NFκB activity), showed a drastic reduction in the expression levels of A2A induced by LPS (Fig. 3C). However, A2B receptor expression was only slightly diminished in this cell line (Fig. 3C). We also evaluated the contribution of IRF-3, another transcription factor directly activated by LPS, to A2 receptor expression, in IRF3+/+ and IRF3−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages activated by LPS. Expression of the A2A receptor was not affected by the lack of IRF3; however, A2B receptor expression was significantly diminished (supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, these results show that different signaling events control the induction by LPS of A2A and A2B receptors in murine macrophages.

Adenosine Cooperates with LPS to Increase pfkfb3 Promoter Activity

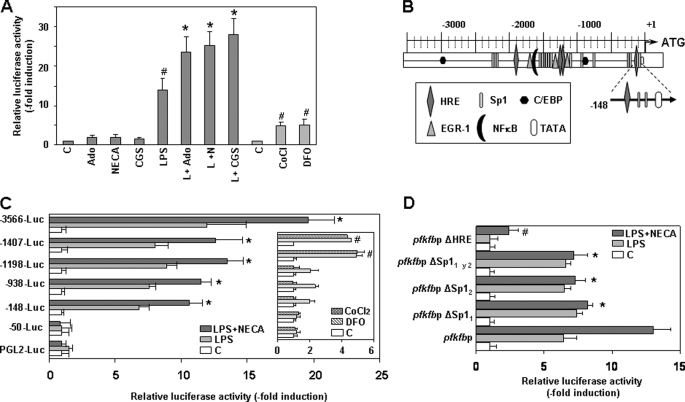

To investigate the mechanism responsible for the increased expression of pfkfb3 in macrophages activated by LPS, we studied both in the absence or in the presence of adenosine or adenosine receptor agonists, the activity of the human pfkfb3 promoter, previously characterized (17). In our studies, we used Raw 264.7 cells, which conserve the pfkfb3 expression pattern observed in bone marrow-derived macrophages, peritoneal macrophages, and human monocyte/macrophages when treated with LPS (data not shown). We transfected this cell line with a construct in which luciferase expression was driven by a 3,566-bp fragment from the human pfkfb3 promoter. As shown in Fig. 4A, adenosine, CGS1680, or NECA by themselves exerted little effect on pfkfb3 promoter activity, but they all cooperated with LPS to increase its effect. The activity of the pfkfb3 promoter increased about 15-fold by LPS alone, an induction level similar to that observed with the endogenous pfkfb3 gene in Raw 264.7 cells (data not shown) or human monocytes/macrophages stimulated by LPS (Fig. 1A) but higher than that observed in LPS-activated murine peritoneal macrophages (about 4-fold, Figs. 1 and 2). Activation of A2 receptors enhanced the promoter activity induced by LPS by ∼2-fold, thus reaching total induction levels close to 30-fold. This promoter behavior was coherent with the increased expression levels of the endogenous pfkfb3 gene observed in macrophages (Fig. 2A) and Raw 264.7 cells (data not shown) treated with LPS or/and A2 receptor agonists.

FIGURE 4.

Specific regions of the pfkfb3 promoter mediate its transcriptional induction by LPS and further up-regulation by adenosine and A2 receptor agonists. A, Raw 264.7 cells were transiently cotransfected with a pGL2-basic luciferase expression vector, containing 3,566 bp of the human pfkfb3 gene promoter, and a β-galactosidase expression vector. Cells were activated for 18 h with LPS (100 ng/ml) and/or adenosine (Ado) (100 μm), CGS21680 (CGS) (2 μm), or NECA (10 μm), or treated with deferoxamine (DFO) (200 μm) or CoCl2 (200 μm). Transfections were performed in triplicate. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of the luciferase activity determined in at least three independent transfection experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus LPS treatment; #, p < 0.05 versus control. B, schematic representation of the pfkfb3 promoter with its putative regulatory elements. C, Raw 264.7 cells were transiently transfected with pGL2-basic luciferase expression vectors containing various lengths of the human pfkfb3 gene promoter 5′-flanking region and a β-galactosidase expression vector as a transfection control. Cells were activated for 18 h with LPS or LPS plus NECA or treated with deferoxamine (DFO) or CoCl2. *, p < 0.05 versus LPS treatment; #, p < 0.05 versus control. D, activity of pfkfb3 minimal promoter following site-directed mutations of the HRE and the two Sp1-binding sites. In all cases, transfections were performed in triplicate. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent transfection experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus LPS plus NECA-treated control promoter; #, p < 0.05 versus its own control.

pfkfb3 expression is induced in different cell types by hypoxia (17). We evaluated the effect of two hypoxia mimics, cobalt chloride (CoCl2) and the iron chelator deferoxamine, in the activity of the human pfkfb3 promoter in macrophages. Promoter activity increased in both cases by about 5-fold, an induction level lower than that observed with LPS alone or LPS with A2 receptor agonists. No cooperation between hypoxia mimics and adenosine receptor agonists was observed (data not shown).

We studied the DNA regions required for LPS and adenosine to increase pfkfb3 promoter activity by using a series of promoter constructs (see promoter diagram shown in Fig. 4B) containing successive deletions from the 5′ end, as described previously (17). For each construct, the fold increase in luciferase activity, elicited by either LPS alone or together with NECA, was determined over basal luciferase activity. As shown in Fig. 4C, 5′ deletion mutants revealed that sequences between −3,566 and −148 from the transcription start site did not substantially affect induction of the pfkfb3 gene promoter by LPS and NECA, although some variations in inducibility were observed. In contrast, both effects were completely abolished by deleting the region between positions −148 and −50. These results show that sequences between −148 and −50 are sufficient for LPS and A2R agonist induction of the pfkfb3 gene promoter.

Previous studies have identified two proximal hypoxia-response element sequences (HRE) between nucleotides 1,269 and 1,297 of the pfkfb3 gene promoter (17). This region is the major hypoxia-responsive region of this gene, and it is essential for the hypoxia-induced transcription of the pfkfb3 gene promoter in macrophages, as showed at the right panel of Fig. 4C.

Accordingly to these data, some differences could be appreciated between pfkfb3 gene promoter induction by LPS/A2R agonists and by hypoxia mimics. First, the level of induction was higher with LPS than with hypoxia mimics in macrophages. The second difference resided on the sequences responsible for the induction. Stimulation of the pfkfb3 promoter by LPS essentially depended on proximal promoter sequences from position −148 to −50, whereas induction by hypoxia mimics was mainly observed in constructs containing the region between nucleotides 1,269 and 1,297.

Sequence analysis of the proximal pfkfb3 promoter (−148 nucleotides) revealed two binding sites for the transcription factor Sp1 (starting at −72 and −97 nucleotides, respectively) and one HRE sequence (107 nucleotides) (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 4D, site-directed mutagenesis of the Sp1 transcription factor-binding sites revealed that Sp1 is a key protein for adenosine cooperation with LPS in the induction of pfkfb3 promoter activity, for each one of the Sp1-binding site mutations are individually sufficient to eliminate the adenosine-dependent induction of the pfkfb3 promoter without affecting induction by LPS. However, mutation of the HRE-binding site completely abolishes pfkfb3 promoter induction by LPS alone, although LPS in combination with the A2 receptor agonist NECA still results in a little induction. These results point at HIF proteins as being responsible for LPS-dependent induction of the pfkfb3 promoter (Fig. 4D).

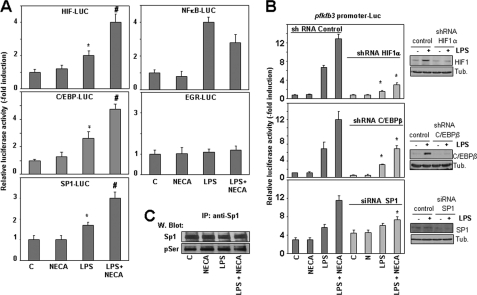

Analysis of the Transcription Factors Involved in pfkfb3 Induction by LPS/A2R Agonists

In addition to Sp1 and HRE, multiple binding sites for relevant transcription factors have been previously identified in the pfkfb3 gene promoter, including NFκB, C/EBP, EGR-1, and estrogen receptor-binding elements, among others (Fig. 4B) (17). To identify additional transcription factors that could modulate pfkfb3 induction by LPS/A2R agonists, we analyzed the effect of LPS and adenosine/NECA in the activity of proteins potentially capable of binding to specific pfkfb3 promoter sequences and related to the LPS or the adenosine response. Reporter constructs carrying binding sites for HIF1, NFκB, C/EBP, Sp1, and EGR-1 were transfected into Raw 264.7 cells, which were stimulated afterward with LPS, NECA, or both. The results showed that the activity of HIF1, C/EBP, and Sp1 reporter constructs increased upon activation with LPS, and this activity was enhanced by the addition of NECA (Fig. 5A). On the contrary, NFκB activity increased with LPS, but it was inhibited by NECA, whereas EGR-1 reporter activity was not affected by either treatment.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis of the transcription factors involved in pfkfb3 induction by LPS and A2 receptor agonists. A, transcriptional activity of reporter constructs carrying binding sites for HIF1, NFκB, C/EBP, SP1, or EGR-1 transfected in Raw 264.7 cells stimulated with LPS, NECA, or both. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus LPS treatment. B, analysis of pfkfb3 promoter activity in Raw 264.7 cells transfected with control, HIF1α, cEBPβ shRNAs, or Sp1 siRNA and stimulated for 18 h with LPS and/or NECA. All transfection experiments were performed in triplicate. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent transfection experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control shRNA or siRNA. In each case, efficiency of shRNAs knockdown is shown by Western blot (W blot). C, analysis by Western blot of Sp1 expression and phosphorylation in Raw 264.7 cells activated by LPS, NECA, or both for 6 h. Total cell proteins (1 mg) were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Sp1 antibody and revealed afterward with anti-Ser(P) or anti Sp1 antibodies. A representative experiment out of three is shown.

To further analyze the role of HIF1 and Sp1, previously identified as key transcription factors by site-directed mutations of proximal binding sites, and the role of C/EBP, which possesses several putative binding sites on the pfkfb3 promoter (Fig. 4B), we used an shRNA or siRNA approach to diminish their expression and explore the effects of this decrease on pfkfb3 promoter activity. We first confirmed that specific shRNAs or siRNAs diminished protein expression at least by 80% of control levels. Then we observed (Fig. 5B) that reduced expression of HIF1α greatly decreased pfkfb3 induction by LPS and LPS/A2R agonists, corroborating its key role in LPS-induced pfkfb3 expression. However, enhanced expression of pfkfb3 by A2R agonists was still observed under these circumstances. In line with the results of the site-directed mutagenesis experiments, reduced Sp1 expression clearly blocked the A2R agonist-dependent enhancement of the pfkfb3 promoter activity, whereas basal and LPS-induced pfkfb3 promoter activity levels were slightly up-regulated. However, overexpression of Sp1 increased pfkfb3 promoter activity (supplemental Fig. 3). Reduced expression of C/EBPβ (Fig. 5B) or C/EBPδ (data not shown) also diminishes pfkfb3 induction by LPS and LPS/A2R agonists. Nevertheless, we have not observed changes in the pfkfb3 promoter activity after mutation of a C/EBP-binding site (−855 nucleotides) (data not shown). However, other putative C/EBP-binding sites could be responsible for its effect; moreover, an indirect effect could be involved as well.

We analyzed HIF1α, C/EBPβ, and Sp1 expression in macrophages activated with LPS in the presence or in the absence of A2 receptor agonists. As shown in supplemental Fig. 4, HIF1α mRNA and protein levels increased after LPS treatment. Adenosine or NECA exerted little effect by themselves on HIF1α expression, but both A2 agonists cooperated with LPS to increase it. Similarly, LPS induced the expression of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ proteins, and this induction was further enhanced by NECA 3 h after LPS treatment. At this time, using macrophage nuclear extracts, we also observed a cooperative effect between LPS and NECA to trigger protein binding to a consensus C/EBP sequence. Expression of C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ proteins also increased pfkfb3 promoter activity (supplemental Fig. 5).

However, in agreement with previously reported results (38, 39), we did not observe changes in Sp1 expression after macrophage activation with LPS in the presence or in the absence of A2 agonists (Fig. 5C). As the activity of Sp1 can be modulated by post-translational modifications, we evaluated whether its phosphorylation state changed in the course of macrophage activation with LPS or A2 receptor agonists. As shown in Fig. 5C, similar Sp1 Ser(P) content was detected in all conditions. Thus, other post-translational modifications, different from phosphorylation, are probably involved in Sp1 activation (40).

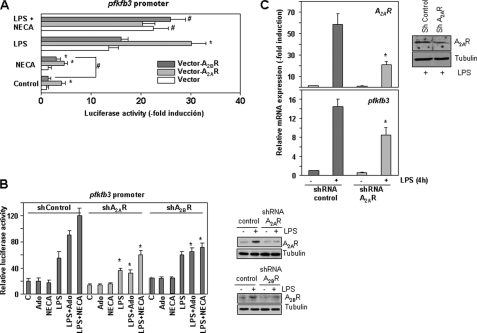

A2A Receptors Are Essential for LPS and Adenosine Induction of pfkfb3 Expression

To assess the role of both A2A and A2B adenosine receptors in pfkfb3 induction, we evaluated the expression of this gene in the presence of ZM 241385 or MRS1754, which are A2A and A2B receptor antagonists, respectively. Both inhibitors diminished the induction of pfkfb3 by a combination of LPS and A2R agonists by around 40%. Surprisingly, both inhibitors also affected to a similar extent the induction of pfkfb3 by LPS alone, arguing for a role of A2 receptors in the induction of this gene by LPS (supplemental Fig. 6). To further evaluate the role of these receptors, we overexpressed each of them in Raw 264.7 cells along with the largest pfkfb3 promoter construct. As shown in Fig. 6A, expression of A2A, but not of A2B receptor, in the absence of any exogenous stimulation, increased the promoter activity by about 5-fold. Treatment with NECA did not increase further the activity of the pfkfb3 promoter in cells transfected with the A2A receptor, but increased its activity in cells overexpressing the A2B receptor. These differences are probably related to the different affinities of each receptor for adenosine (0.7 μm for A2A and 24 μm for A2B (35)) and suggest that endogenous adenosine production by macrophages is sufficient to activate A2A but not A2B receptors. Induction of the pfkfb3 promoter by LPS is also stronger when A2A rather than A2B is overexpressed, but as observed previously in the absence of LPS, treatment with NECA was unable to further increase luciferase activity by A2A, although it increased pfkfb3 promoter activity in cells transfected with the A2B receptor.

FIGURE 6.

A2A and A2B receptors collaborate to increase LPS-induced pfkfb3 expression. A, overexpression of A2A or A2B receptors increases pfkfb3 promoter activity in macrophages. Raw 264.7 cells were cotransfected with −3,566-pfkfb3-Luc and A2A or A2B receptor expression vectors and treated with LPS, NECA, or both for 18 h. A β-galactosidase expression vector was used as a transfection control. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of the luciferase activity determined in at least three independent transfection experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control transfection; #, p < 0.05 versus NECA treatment. B, effect of A2A or A2B receptor shRNAs in the activity of the −3,566-pfkfb3 promoter construct. Raw 264.7 cells were transiently cotransfected with −3,566-pfkfb3-Luc and control or A2A or A2B receptor shRNAs and treated with LPS, NECA, or both for 18 h. A β-galactosidase expression vector was used as a transfection control. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of the luciferase activity determined in at least three independent transfection experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control transfection. C, expression of A2A receptors and pfkfb3 mRNAs in stably transfected Raw 264.7 cells expressing control or A2A receptor shRNAs and activated or not with LPS or LPS/NECA. *, p < 0.05 versus control shRNA. In each case efficiency of shRNAs knockdown is shown by Western blot.

In an additional approach to clarify the role of A2A and A2B receptors in pfkfb3 induction by LPS and adenosine, we transiently transfected Raw 264.7 cells with the −3,566 pfkfb3 promoter construct and A2A or A2B receptor shRNAs. As shown in Fig. 6B, the LPS-induced increase in pfkfb3 promoter activity diminished in the presence of A2A shRNA, but it was not affected by A2B shRNA. However, again, both A2A andA2B shRNAs diminished the effects caused by adenosine or NECA. To confirm the role of A2A receptor in the LPS-dependent induction of pfkfb3 gene expression, we generated stably transfected Raw 264.7 cells with a control or with an A2A receptor shRNA to decrease its expression. As shown in Fig. 6C, diminished A2A receptor expression levels resulted in reduced pfkfb3 expression after macrophage activation by LPS. Taken together, these results suggest that, although both A2A and A2B receptors are implicated, the A2A receptor is essential for the induction of pfkfb3 expression by LPS when low concentrations of adenosine are present in the medium. A2B receptors are less relevant in this role, but they can further increase pfkfb3 expression when adenosine accumulates in stressful situations.

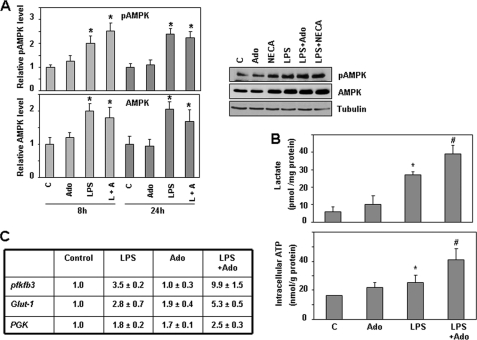

LPS Increases AMP Kinase Activity in Macrophages

Different reports (41, 42) have shown that PFKFB3 activity can be modulated by phosphorylation at Ser-461 by the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is activated by phosphorylation when the AMP/ATP ratio is elevated and can switch on catabolic pathways by different mechanisms, including phosphorylation of metabolic enzymes (43), as described for the PFKFB3 isozyme (41). To evaluate the possible contribution of LPS and adenosine toward the activation of AMPK to modulate PFKFB3 isozyme activity, we analyzed AMPK phosphorylation and expression in macrophages activated by LPS and/or adenosine. As shown in Fig. 7A, AMPK phosphorylation increases over the control levels in long term LPS-activated macrophages (8–24 h). When AMPK expression was analyzed, higher levels of protein could be observed after LPS treatment. No differences between LPS and LPS/adenosine conditions were observed. These data lead us to conclude that increased AMPK activity, due to increased AMPK expression and phosphorylation, is present in long term activated macrophages, which could contribute also to increased PFKFB3 activity and Fru-2,6-P2 accumulation in these cells.

FIGURE 7.

Adenosine and LPS cooperate to increase the glycolytic flux and ATP production in macrophages. A, analysis by Western blot of pAMPK and AMPK levels in macrophages activated with LPS (100 ng/ml) and/or adenosine (100 μm) or NECA (10 μm) for different times. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Tubulin expression is used as a reference. *, p < 0.05 versus control condition. A representative Western blot is also shown. B, determination of lactate production (upper panel) and intracellular ATP levels (lower panel) in macrophages activated as described previously for 12 or 24 h, respectively. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control; #, p < 0.05 versus LPS treatment. C, expression analysis by RT-PCR of different genes implicated in glucose metabolism in macrophages stimulated for 4 h with LPS and/or NECA. Results represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. PGK, phosphoglycerate kinase.

Increased Lactate Production and ATP Supply in Macrophages Activated by LPS and Adenosine

As the glycolytic flux is mainly controlled by 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase (9), and the main consequence of enhanced glycolytic function is an increase in lactate production, we analyzed this metabolite in macrophages activated by LPS and adenosine. As reported previously (5), increased levels of lactate are observed in LPS-activated macrophages (Fig. 7B). Statistically significant higher lactate levels, over those reached with LPS alone, were observed after treatment with adenosine.

We also analyzed the ATP levels in activated macrophages. In agreement with previous data (34), decreased ATP levels were observed during the first hours after LPS treatment (data not shown). However, long term macrophage activation with LPS (from 12 to 36 h) resulted in increased ATP levels (Fig. 7B). This increase was enhanced by adenosine. Thus, it appears that adenosine cooperates with macrophage-activating signals to increase energy supply, permitting macrophage long term activity. Along this line, besides PFKFB3, expression of other glycolytic enzymes, such as PGK and the glucose transporter Glut1, is also increased by LPS and A2 receptor agonists, as shown in Fig. 7C.

DISCUSSION

Macrophages and phagocytic cells accomplish their defensive roles in hostile environments, poor in oxygen and rich in free radicals able to block electron transport in mitochondria. In these conditions, ATP supply by anaerobic glycolysis is an essential source of energy for these cells. In this work, we show that molecules present in the macrophage microenvironment, particularly adenosine, cooperate with some pathogen-induced activation signals to increase the glycolytic flux through the induction of pfkfb3 expression and PFKFB3 isozyme activity. Our results identify, for the first time, pfkfb3 as a gene synergistically up-regulated by LPS and adenosine, which produces a synergistic effect on the expression and activity of PFKFB3. We have analyzed the molecular mechanisms underlying the cooperative induction of pfkfb3 expression by LPS and adenosine, and we concluded that different processes are implicated. First, LPS induces the expression of A2A and A2B receptors, increasing the sensitivity of the macrophage to adenosine. Second, both LPS and adenosine increase the expression of HIF1α, C/EBPβ, and C/EBPδ, which are key transcription factors for pfkfb3 expression. Third, adenosine increases Sp1 activation, which cooperatively up-regulates pfkfb3 expression. Moreover, long term LPS treatment induces AMPK activation, favoring phosphorylation of PFKFB3 at Ser-461, and thus increasing its kinase activity. Therefore, increased expression and phosphorylation of the PFKFB3 isozyme must be responsible for the increased levels of Fru-2,6-P2 and glycolytic rate observed in activated macrophages in the presence of adenosine.

Bacterial LPS and inflammatory cytokines have been reported to modify the expression of adenosine receptors, although somewhat different results are reported in the literature. A small (<2-fold) increase in the expression of the A2A receptor mRNA has been reported in the case of human monocytic cell lines (44). However, Murphree et al. (37) reported greater than 100-fold increase in A2A receptor expression in human or mice macrophages, in addition to a concomitant up-regulation of the A2B receptor. Our results agree with this last work in that macrophage activation by LPS significantly increases A2A and A2B adenosine receptors. On the contrary, A1 and A3 receptors are down-regulated by proinflammatory signals. A2A and A2B receptors increase cAMP levels, whereas A1 and A3 exert the opposite effect (35); thus macrophage activation by LPS causes an adenosine receptor isoform expression pattern switch that can selectively modify the macrophage phenotype. We have also analyzed the molecular mechanism responsible for this effect and unveiled, by using genetic approaches, that NFκB is a key transcription factor in LPS-induced A2A receptor expression, whereas IRF3 is not implicated. On the contrary, A2B receptor expression depends on IRF3 and is less affected by NFκB. These results suggest that different Toll receptor agonists would induce different adenosine receptor expression patterns depending on the main transcription factors activated by the similar, but not identical, Toll receptor signaling pathways, thus modifying in this way macrophage sensitivity to adenosine.

One of the more surprising findings of this work is that the endogenous production of adenosine by activated macrophages functions as a second messenger in the LPS signaling pathway leading to increased pfkfb3 expression. A role for adenosine in the induction of IL-10 synthesis by Escherichia coli has also been described (45). Therefore, increasing evidence shows that endogenous adenosine production by macrophages mediates part of the effects triggered by LPS on macrophage gene expression.

In the last decade, multiple evidence has shown that adenosine, A2A, and, to a lesser extent, A2B receptors exert a crucial anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effect (reviewed in Refs. 21, 35), essential in limiting macrophage activity and protecting surrounding tissues of collateral damage during infection. In vivo genetic experiments have confirmed the anti-inflammatory role of A2 receptors (26). Our results are consistent with these observations, as they show that adenosine diminishes TNFα expression and increases iNOS synthesis, which also agrees with previous reports (46). In this context, we have observed increased pfkfb3, PGK, and Glut1 gene expression (Fig. 7). Thus adenosine, besides diminishing macrophage activation, seems to cooperate with LPS to increase the expression of proteins implicated in glucose transport and catabolism. Among them, PFKFB3 is especially relevant due to the essential role that the metabolite it produces, Fru-2,6-P2, plays in the control of the glycolytic flux (11).

Our analysis of the pfkfb3 promoter activity and studies performed with specific shRNAs or siRNAs identified HIF1α as a key transcription factor implicated in LPS induction (Fig. 6). HIF1 is an essential mediator allowing cell adaptation to low oxygen levels. Cramer et al. (5), using conditional gene targeting deletion of HIF1α in the myeloid cell lineage of mice, have clearly shown that this transcription factor is essential for macrophage energy supply and function and for the orchestration of the inflammatory response in vivo. Although hypoxia is the main cause of HIF1α activation, an increasing body of evidence indicates that this transcription factor may also be up-regulated by nonhypoxic stimuli. Indeed, cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-1β, and inflammatory mediators, such as NO, have been shown to increase HIF1α levels during normoxia (47–49). This induction involves transcriptional (47) and post-transcriptional mechanisms for HIF1 stabilization (50, 51). In macrophages, adenosine, through its A2 receptor, increases HIF1α levels in a process depending on protein kinase C and PI3K pathways, which involve transcriptional and, to a large extent, translational mechanisms (52). HIF1α has been previously related to adenosine and LPS cooperation in the expression of VEGF (25). Our results extend these observations and show the essential role played by HIF1α in LPS and adenosine-induced expression of pfkfb3 in macrophages.

C/EBP transcription factors play a fundamental role in the process of macrophage differentiation and in the regulation of different functions in activated macrophages (53–55). Toll-4 receptors increase C/EBPβ expression, favoring the transcription of multiple proinflammatory genes, such as IL-6, TNFα, and iNOS (56). C/EBPδ is also induced after LPS treatment by a mechanism depending on NFκB (57). Indeed, it has been recently described that C/EBPδ cooperates with NFκB to maintain long term gene expression in persistent Toll receptor signaling (57). Our results show that LPS and adenosine cooperate to increase C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ expression and that all these proteins are able to increase pfkfb3 promoter activity. Expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, induced by LPS, is mediated by C/EBPβ (39, 45), and this process depends on the expression of A2 receptors (45). Transduction through these receptors implicates the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A, which phosphorylates the transcription factor CREB (58). Recently, it has been described that CREB increases the expression of C/EBPβ (45). Activation of CREB has been also related to the strong anti-inflammatory properties of A2 receptors by competing with NFκB and other transcription factors for the important cofactor CREB-binding protein.

Induction of HIF1α and C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ activity by adenosine in activated macrophages has been previously reported to explain the cooperative effect of adenosine and bacterial components in VEGF and IL-10 expression, respectively (25, 45). However, in this work we show, for the first time, that the transcription factor Sp1 is also implicated in the regulation of gene expression by adenosine (Fig. 6). Sp1 was thought to serve mainly as a constitutive activator for housekeeping genes, but growing evidence shows that post-translational modifications can modulate its transcriptional activity (reviewed in Ref. 40). Sp1 can be phosphorylated by various kinases at different sites. Decreased Sp1 phosphorylation has been related to the expression of IL-21 receptor in activated T cells (59). On the contrary, increased expression of apolipoprotein A-I by the action of Sp1 seems to be modulated in its phosphorylation by protein kinase A and C, among others (60, 61). The influence of phosphorylation on Sp1 activity is not completely understood. Although it was tempting to speculate that activation of protein kinase A after adenosine receptor triggering is implicated in the increased Sp1 activity observed in macrophages activated with LPS and A2 receptor agonists, our results discard this hypothesis, because we observed that the increased Sp1 activity does not appear to depend on Ser phosphorylation. Further work is needed to clarify the post-translational modifications that explain these molecular events.

Expression of pfkfb3 occurs mainly in proliferative and transformed cells (13, 14). Previous reports have also described its expression in human and mouse macrophages, astrocytes, and monocytes (14, 15, 62). Besides, there is evidence of pfkfb3 up-regulation by hypoxia, serum, insulin, and proinflammatory molecules (14, 17, 62, 63). In addition to transcription, PFKFB3 isozyme activity is regulated by phosphorylation by AMPK at Ser-461, which increases its Vmax without affecting its Km values (11). Our results show that expression of the pfkfb3 gene is highly up-regulated in macrophages activated by LPS and adenosine agonists by increasing the transcriptional activity of its promoter. In addition, our results show increased levels of activated and phosphorylated AMPK in long term LPS-activated macrophages, which further increase PFKFB3 activity through AMPK-dependent phosphorylation in those cells. This effect could be related to NO accumulation, as it has been described in astrocytes, in which increased NO levels results in mitochondrial inhibition and AMPK activation (15). Increased glycolytic flux originated by the NO/AMPK induction of PFK2.3 activity increases, in turn, the resistance of astrocytes to apoptosis (15). Elevated glycolysis also seems to be essential for the activation of other immune cells, such as T lymphocytes. Although the energetic yield of glycolysis is much smaller than that of glucose oxidation in the mitochondria, in conditions of unlimited glucose supply, glycolysis produces ATP substantially faster, so the stimulation of glucose uptake and glycolysis is also essential for proper T cell activation, and a defective energy supply results in the death of T cells by apoptosis (64). Therefore, we can hypothesize that the up-regulation of PFKFB3 isozyme expression observed in activated macrophages could also favor their viability in the inflammatory microenvironment. Along this line, a recent work reports that diminishing PFKFB3 expression increases macrophage apoptosis and limits macrophage activation (62).

In summary, our results demonstrate an important role for adenosine signaling in inflammation. Besides its crucial anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, essential in limiting macrophage activity and protecting surrounding tissues of collateral damage, adenosine, through A2 receptor activation, cooperates with signaling pathways triggered by some pathogen components to increase glycolytic flux and energy supply in macrophages, favoring the expression and activation of the key glycolytic isozyme PFKFB3. This process could be essential in protecting the viability of macrophages to develop their long term defense and reparative functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cristina Panadero and Ángela Ballesteros for their invaluable technical support and Dr. J. J. Ramírez, Dr. M. J. Ruiz-Hidalgo, and Dr. V. Baladrón for discussions and advice. We also thank Dr. Ana Pérez-Castillo (Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid) and Dr. Marta Giralt (Universitat de Barcelona) for their generous gifts of C/EBPs reporter plasmids and expression vectors.

This work was supported by Grant PI060449 from the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Grant BFU 2009-07380 from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Grant SAN06-015 from Consejería de Sanidad, and Grant PII1/09-0211-7101 from the Consejería de Educación y Ciencia, Junta de Comunidades de Castilla-La Mancha, Spain.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–6.

- Fru-2,6-P2

- fructose 2,6-bisphosphate

- C/EBPβ

- CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β

- NECA

- 5′-(N-ethylcarboxamido)adenosine

- A2R

- A2 receptor

- HRE

- hypoxia-response element

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. (2003) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 2195–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kay N. E., Bumol T. F., Douglas S. D. (1980) J. Reticuloendothel. Soc. 28, 367–379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turner L., Scotton C., Negus R., Balkwill F. (1999) Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 2280–2287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cramer T., Yamanishi Y., Clausen B. E., Förster I., Pawlinski R., Mackman N., Haase V. H., Jaenisch R., Corr M., Nizet V., Firestein G. S., Gerber H. P., Ferrara N., Johnson R. S. (2003) Cell 112, 645–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawaguchi T., Veech R. L., Uyeda K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 28554–28561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kempner W. (1939) J. Clin. Invest. 18, 291–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vats D., Mukundan L., Odegaard J. I., Zhang L., Smith K. L., Morel C. R., Wagner R. A., Greaves D. R., Murray P. J., Chawla A. (2006) Cell Metab. 4, 13–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krebs H. A. (1972) Essays Biochem. 8, 1–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pilkis S. J., Claus T. H., Kurland I. J., Lange A. J. (1995) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 799–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Okar D. A., Manzano A., Navarro-Sabatè A., Riera L., Bartrons R., Lange A. J. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Duran J., Obach M., Navarro-Sabate A., Manzano A., Gómez M., Rosa J. L., Ventura F., Perales J. C., Bartrons R. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 4555–4568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Atsumi T., Chesney J., Metz C., Leng L., Donnelly S., Makita Z., Mitchell R., Bucala R. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 5881–5887 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chesney J., Mitchell R., Benigni F., Bacher M., Spiegel L., Al-Abed Y., Han J. H., Metz C., Bucala R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3047–3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Almeida A., Moncada S., Bolaños J. P. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Riera L., Manzano A., Navarro-Sabaté A., Perales J. C., Bartrons R. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1589, 89–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Obach M., Navarro-Sabaté A., Caro J., Kong X., Duran J., Gómez M., Perales J. C., Ventura F., Rosa J. L., Bartrons R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 53562–53570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riera L., Obach M., Navarro-Sabaté A., Duran J., Perales J. C., Viñals F., Rosa J. L., Ventura F., Bartrons R. (2003) FEBS Lett. 550, 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilroy D. W., Lawrence T., Perretti M., Rossi A. G. (2004) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 401–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haskó G., Cronstein B. N. (2004) Trends Immunol. 25, 33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sitkovsky M. V., Ohta A. (2005) Trends Immunol. 26, 299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cronstein B. N. (1994) J. Appl. Physiol. 76, 5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sitkovsky M., Lukashev D. (2005) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 712–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pinhal-Enfield G., Ramanathan M., Hasko G., Vogel S. N., Salzman A. L., Boons G. J., Leibovich S. J. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 163, 711–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramanathan M., Pinhal-Enfield G., Hao I., Leibovich S. J. (2007) Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 14–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ohta A., Sitkovsky M. (2001) Nature 414, 916–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sitkovsky M. V., Lukashev D., Apasov S., Kojima H., Koshiba M., Caldwell C., Ohta A., Thiel M. (2004) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22, 657–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lukashev D., Ohta A., Apasov S., Chen J. F., Sitkovsky M. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Castrillo A., Joseph S. B., Vaidya S. A., Haberland M., Fogelman A. M., Cheng G., Tontonoz P. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 805–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Escoll P., del Fresno C., García L., Vallés G., Lendínez M. J., Arnalich F., López-Collazo E. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311, 465–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Van Schaftingen E., Lederer B., Bartrons R., Hers H. G. (1982) Eur. J. Biochem. 129, 191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hohorst H. J., Arese P., Bartels H., Stratmann D., Talke H. (1965) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 119, 974–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Navarro-Sabaté A., Manzano A., Riera L., Rosa J. L., Ventura F., Bartrons R. (2001) Gene 264, 131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kempf V. A., Lebiedziejewski M., Alitalo K., Wälzlein J. H., Ehehalt U., Fiebig J., Huber S., Schütt B., Sander C. A., Müller S., Grassl G., Yazdi A. S., Brehm B., Autenrieth I. B. (2005) Circulation 111, 1054–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haskó G., Linden J., Cronstein B., Pacher P. (2008) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 759–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murdoch C., Muthana M., Lewis C. E. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 6257–6263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Murphree L. J., Sullivan G. W., Marshall M. A., Linden J. (2005) Biochem. J. 391, 575–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu Y. W., Chen C. C., Wang J. M., Chang W. C., Huang Y. C., Chung S. Y., Chen B. K., Hung J. J. (2007) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 3282–3294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu Y. W., Chen C. C., Tseng H. P., Chang W. C. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18, 1492–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tan N. Y., Khachigian L. M. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 2483–2488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marsin A. S., Bouzin C., Bertrand L., Hue L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30778–30783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bando H., Atsumi T., Nishio T., Niwa H., Mishima S., Shimizu C., Yoshioka N., Bucala R., Koike T. (2005) Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 5784–5792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kahn B. B., Alquier T., Carling D., Hardie D. G. (2005) Cell Metab. 1, 15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Khoa N. D., Montesinos M. C., Reiss A. B., Delano D., Awadallah N., Cronstein B. N. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 4026–4032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Csóka B., Németh Z. H., Virág L., Gergely P., Leibovich S. J., Pacher P., Sun C. X., Blackburn M. R., Vizi E. S., Deitch E. A., Haskó G. (2007) Blood 110, 2685–2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haskó G., Pacher P. (2008) J. Leukocyte Biol. 83, 447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jung Y., Isaacs J. S., Lee S., Trepel J., Liu Z. G., Neckers L. (2003) Biochem. J. 370, 1011–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jung Y. J., Isaacs J. S., Lee S., Trepel J., Neckers L. (2003) FASEB J. 17, 2115–2117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sandau K. B., Zhou J., Kietzmann T., Brüne B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39805–39811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pagé E. L., Robitaille G. A., Pouysségur J., Richard D. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 48403–48409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Blouin C. C., Pagé E. L., Soucy G. M., Richard D. E. (2004) Blood 103, 1124–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. De Ponti C., Carini R., Alchera E., Nitti M. P., Locati M., Albano E., Cairo G., Tacchini L. (2007) J. Leukocyte Biol. 82, 392–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yeamans C., Wang D., Paz-Priel I., Torbett B. E., Tenen D. G., Friedman A. D. (2007) Blood 110, 3136–3142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Akira S., Kishimoto T. (1997) Adv. Immunol. 65, 1–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Natsuka S., Akira S., Nishio Y., Hashimoto S., Sugita T., Isshiki H., Kishimoto T. (1992) Blood 79, 460–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Uematsu S., Kaisho T., Tanaka T., Matsumoto M., Yamakami M., Omori H., Yamamoto M., Yoshimori T., Akira S. (2007) J. Immunol. 179, 5378–5386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Litvak V., Ramsey S. A., Rust A. G., Zak D. E., Kennedy K. A., Lampano A. E., Nykter M., Shmulevich I., Aderem A. (2009) Nat. Immunol. 10, 437–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Németh Z. H., Leibovich S. J., Deitch E. A., Sperlágh B., Virág L., Vizi E. S., Szabó C., Haskó G. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 883–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wu Z., Kim H. P., Xue H. H., Liu H., Zhao K., Leonard W. J. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 9741–9752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zheng X. L., Matsubara S., Diao C., Hollenberg M. D., Wong N. C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13822–13829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zheng X. L., Matsubara S., Diao C., Hollenberg M. D., Wong N. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31747–31754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rodríguez-Prados J. C., Través P. G., Cuenca J., Rico D., Aragonés J., Martín-Sanz P., Cascante M., Boscá L. (2010) J. Immunol. 185, 605–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Minchenko A., Leshchinsky I., Opentanova I., Sang N., Srinivas V., Armstead V., Caro J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6183–6187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jones R. G., Thompson C. B. (2007) Immunity 27, 173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.