Abstract

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1) is an endothelial cell protein that transports lipoprotein lipase (LPL) from the subendothelial spaces to the capillary lumen. GPIHBP1 contains two main structural motifs, an amino-terminal acidic domain enriched in aspartates and glutamates and a lymphocyte antigen 6 (Ly6) motif containing 10 cysteines. All of the cysteines in the Ly6 domain are disulfide-bonded, causing the protein to assume a three-fingered structure. The acidic domain of GPIHBP1 is known to be important for LPL binding, but the involvement of the Ly6 domain in LPL binding requires further study. To assess the importance of the Ly6 domain, we created a series of GPIHBP1 mutants in which each residue of the Ly6 domain was changed to alanine. The mutant proteins were expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and their expression level on the cell surface and their ability to bind LPL were assessed with an immunofluorescence microscopy assay and a Western blot assay. We identified 12 amino acids within GPIHBP1, aside from the conserved cysteines, that are important for LPL binding; nine of those were clustered in finger 2 of the GPIHBP1 three-fingered motif. The defective GPIHBP1 proteins also lacked the ability to transport LPL from the basolateral to the apical surface of endothelial cells. Our studies demonstrate that the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 is important for the ability of GPIHBP1 to bind and transport LPL.

Keywords: Endothelium, Lipase, Lipolysis, Lipoprotein Metabolism, Protein-Protein Interactions, GPIHBP1, LPL, Ly6 Domain

Introduction

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored high density lipoprotein-binding protein 1 (GPIHBP1), a member of the lymphocyte antigen 6 (Ly6)2 family of proteins, is expressed in microvascular endothelial cells and is responsible for shuttling lipoprotein lipase (LPL) from the interstitial spaces to the capillary lumen. Once inside capillaries, LPL hydrolyzes the triglycerides in plasma lipoproteins (1). In the absence of GPIHBP1, LPL is mislocalized to the extravascular spaces and never reaches the capillary lumen, resulting in severe hypertriglyceridemia (chylomicronemia) (2).

The hallmark of the Ly6 protein family, numbering ∼25–30 different proteins in mammals, is an ∼80-amino acid motif containing 8 or 10 cysteines arranged in a characteristic spacing pattern. Each cysteine is disulfide-bonded, generating a three-fingered motif, with each finger composed largely of β-pleated sheets (3). Aside from the cysteine residues that define the Ly6 domain, most family members have little homology at the amino acid level. Many Ly6 proteins in mammals, including GPIHBP1, CD59, and urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (UPAR), are tethered to the plasma membrane by a GPI anchor.

GPIHBP1 is unique among Ly6 proteins in having a strongly acidic domain. In human GPIHBP1, 21 of 26 consecutive amino acids at the amino terminus are aspartic acid or glutamic acid, and similar acidic domains are found in GPIHBP1 proteins in other mammals. The acidic domain is clearly important for binding LPL, which has several well characterized positively charged domains (4–6). When some or all of the acidic residues in the acidic domain are replaced with alanine (7), GPIHBP1 loses its capacity to bind LPL. Also, an antibody against the acidic domain interferes with LPL binding (7).

Several observations have suggested that the Ly6 domain could play a role in LPL binding. For example, when the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 is replaced with the Ly6 domain of CD59, LPL binding is abolished, although the acidic domain is intact (7). To explore the functional importance of the GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain in binding LPL, we performed alanine-scanning mutagenesis (8) on the Ly6 domain. These studies identified the residues required for LPL binding and pointed to a particularly important role for finger 2 of the three-fingered structural domain of GPIHBP1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

GPIHBP1 Constructs and Cell Transfections

The expression vector for S-protein-tagged human GPIHBP1 has been described previously (9). Site-directed mutagenesis with the QuikChange kit (Agilent Technologies) was used to construct a series of mutant GPIHBP1 constructs in which each amino acid in the Ly6 domain (Cys-65 to Cys-136) was replaced with an alanine. All of the mutant constructs were verified by sequencing.

CHO-K1 cells (1–5 × 106) or rat heart microvascular endothelial cells (RHMVECs) (1 × 106) were electroporated with 5 μg of plasmid DNA with the Nucleofector II apparatus (Lonza) and the Cell Line T or HMVEC-L Nucleofector kit (Lonza), respectively.

Production of LPL for Binding Assays

A stable CHO cell line expressing V5-tagged human LPL was obtained from Dr. Mark Doolittle (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA) and adapted for growth in 95% serum-free/protein-free medium (ProCHO-AT from Lonza). Conditioned medium was concentrated 10-fold with Amicon Ultra 30k centrifugal filters (Millipore). The presence of LPL in the conditioned medium was assessed by Western blotting with a mouse monoclonal antibody against the V5 tag (1:200; Invitrogen).

Binding of Human LPL to GPIHBP1-expressing CHO Cells

GPIHBP1-transfected CHO-K1 cells were grown in 24-well tissue culture plates and then incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with V5-tagged human LPL (400 μl/well). In some wells, heparin was added to the medium (final concentration, 500 units/ml). At the end of the incubation, cells were washed six times with ice-cold PBS containing 1 mm MgCl2 and 1 mm CaCl2 (PBS/Mg/Ca); cell extracts were collected in radioimmune precipitation buffer (PBS containing 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.02% SDS) with complete mini EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). GPIHBP1 expression and the amount of LPL bound to cells were assessed by Western blotting. Proteins in cell extracts were size-fractionated on 12% or 4–12% BisTris SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The antibody dilutions for Western blots were 1:1000 for a goat polyclonal antibody against the S-protein tag (Abcam), 1:100 for a mouse monoclonal antibody against the V5 tag (Invitrogen), 1:500 for a rabbit polyclonal antibody against β-actin (Abcam), 1:5000 for an IRdye800-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG, 1:500 for an IRdye800-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG, and 1:2000 for an IRdye680-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (all from Li-Cor). Antibody binding was quantified with an Odyssey infrared scanner (Li-Cor).

Assessing GPIHBP1 Expression on the Cell Surface

To determine if the mutant S-protein-tagged GPIHBP1 proteins reached the cell surface, we compared the amount of GPIHBP1 on the surface of cells with the total amount of GPIHBP1 in cells for each construct. GPIHBP1-transfected CHO-K1 cells plated in triplicate wells of a 24-well plate were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the S-protein tag (10 μg/ml; Abcam) for 2 h at 4 °C in ice-cold PBS/Mg/Ca). At the end of the incubation, cells were washed six times with ice-cold PBS/Mg/Ca, and cell extracts were prepared as described above. To assess the amount of GPIHBP1 on the cell surface, we performed Western blots with an IRdye800-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:800; Li-Cor). To assess the total amount of GPIHBP1 in cells, we performed a Western blot with a goat polyclonal antibody against the S-protein tag (1:1000; Abcam) and an IRdye680-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:5000; Li-Cor). The intensity of each band was quantified with the Li-Cor infrared scanner. The ratio of GPIHBP1 on the cell surface (800-nm channel) to total GPIHBP1 (680-nm channel) was determined for each GPIHBP1 construct and expressed as a percentage of the ratio observed with wild-type GPIHBP1.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

CHO-K1 (1 × 106 cells) were electroporated with 2 μg of either a S-protein-tagged human GPIHBP1 construct or a V5-tagged human LPL expression vector (a gift from Dr. Mark Doolittle), and the cells were mixed and plated on coverslips in 24-well plates. 24 h later, the cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and blocked with 10% donkey serum in PBS/Mg/Ca. Cells were then incubated for 1 h in blocking buffer with a goat polyclonal antibody against the S-protein tag (1:500; Abcam) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against the V5 tag (1:100; Invitrogen), followed by a 30-min incubation with an Alexa 568-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:800; Invitrogen) and an Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:800; Invitrogen). After washing, the cells were stained with DAPI to visualize DNA. Images were recorded with an Axiovert 200M microscope (equipped with a ×63/1.25 oil immersion objective, an AxioCam MRm, and an ApoTome) and processed with the AxioVision 4.6 software (all from Zeiss). Within each experiment, the exposure conditions for each construct were fixed and identical.

LPL Transport Assays

RHMVECs were transfected with either wild-type or mutant human GPIHBP1 constructs or a human CD59 construct (all S-protein-tagged) and grown on fibronectin-coated Millicell filters (Millipore) (1). LPL was added to the basolateral chamber (1), and the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The LPL that was transported to the apical surface of cells was released with heparin (100 units/ml) and dot-blotted, and the signals were quantified with a Li-Cor scanner. In parallel, LPL transport was assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy. For those studies, LPL was added to the basolateral chamber, and cells were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After fixing the cells, LPL was detected with CF568-conjugated monoclonal antibody 5D2 (1:50), and GPIHBP1 was detected with a goat antibody against the S-protein tag (1:100) followed by an Alexa647-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (1:800). A series of images from the bottom to the top of the cell along the z axis were recorded with an Axiovert 200 MOT microscope (Zeiss) and a ×63/1.25 oil immersion objective. Cross-sections of endothelial cells through nuclei were obtained by generating three-dimensional images with Volocity Visualization software version 5.3 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

RESULTS

Alanine-scanning Mutagenesis of GPIHBP1 Ly6 Domain

We generated a series of mutant GPIHBP1 proteins in which each amino acid of the Ly6 domain (Cys-65 to Cys-136) was changed to alanine. For a subset of residues (Thr-80, Ile-93, Gly-101, Leu-103, Thr-104, His-106, Trp-109, Gln-115, Pro-116, Ile-117, Val-121, Gly-123, and Leu-135), we introduced one or more additional amino acid substitutions, some of which had been identified in a hyperlipidemia clinic.

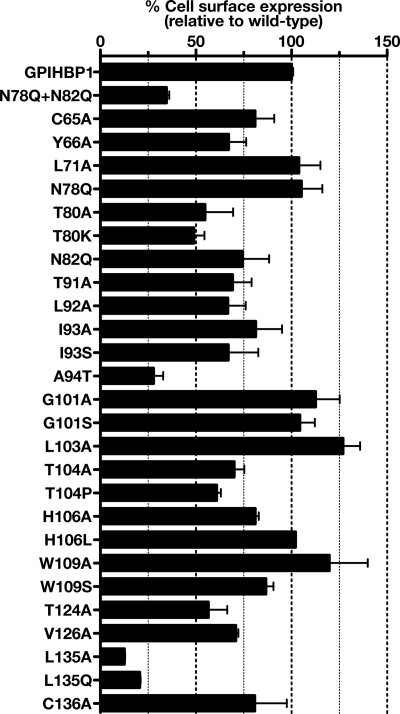

To assess the impact of each amino acid substitution on the cell surface expression of GPIHBP1, CHO K1 cells were electroporated with wild-type or mutant GPIHBP1 constructs, and the total amount of GPIHBP1 in cells and the amount of GPIHBP1 expressed on the cell surface were measured by Western blotting. We then determined, for each mutant, the ratio of cell surface to total GPIHBP1 expression (relative to the ratio for wild-type GPIHBP1, which was set at 100%) (Fig. 1). As a control, we quantified the cell surface expression for a nonglycosylated GPIHBP1 mutant (N78Q/N82Q) because we have shown previously that N-linked glycosylation is important for trafficking of GPIHBP1 to the cell surface (10). As expected, the cell surface/total GPIHBP1 ratio for the nonglycosylated GPIHBP1 mutant was low (35 ± 1.4% of wild-type control). Mutation of the cysteine residues in the Ly6 domain had a significantly smaller effect; the ratio for the different cysteine mutants ranged from ∼70% to nearly 100% (Fig. 1). For the majority of the alanine mutants, the ratio ranged from 66 to 127% (Fig. 1), but a few mutations clearly reduced GPIHBP1 expression at the cell surface. Mutation of the threonine residue (T80A and T80K) within the N-linked glycosylation consensus sequence reduced surface expression to 55 ± 15 and 49 ± 5.5% of wild-type GPIHBP1, respectively. Other mutants with reduced cell surface expression were A94T (28 ± 5.0%), T104P (61 ± 2.2%), T124A (57 ± 9.9%), L135A (13 ± 0.3%), and L135Q (21 ± 0.5%).

FIGURE 1.

Assessing cell surface expression of mutant GPIHBP1 proteins. CHO-K1 cells were electroporated with wild-type or mutant GPIHBP1 constructs. All GPIHBP1 constructs were S-protein-tagged. 24 h after electroporation, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the S-protein tag (10 μg/ml). After washing the cells, we performed Western blots of cell lysates with an antibody against rabbit IgG (to assess the binding of the S-protein antibody to GPIHBP1 on the surface of cells) and a goat polyclonal against the S-protein tag (to assess total levels of GPIHBP1 expression in cells). Band intensities were quantified with a Li-Cor scanner. The amount of GPIHBP1 on the cell surface was normalized to total GPIHBP1 expression and expressed as a percentage of the ratio observed with wild-type GPIHBP1 (set at 100%). The bar graph shows mean ± S.E. (error bars) of triplicate measurements.

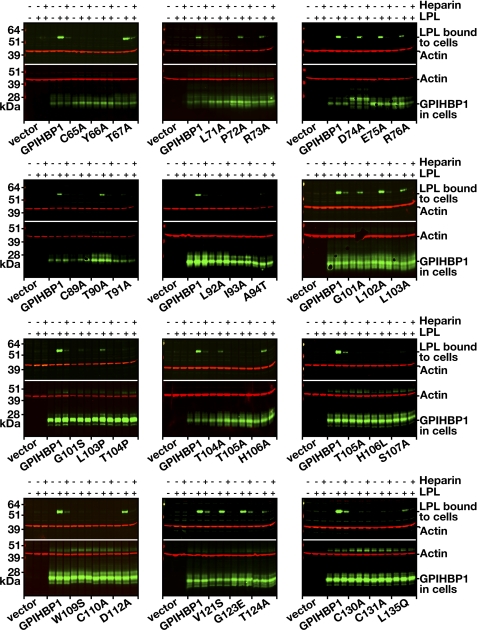

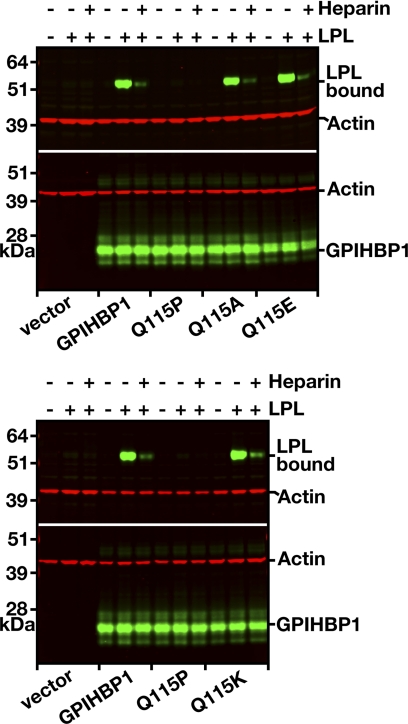

Next, we screened each mutant for its ability to bind LPL, taking advantage of both Western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy assays (Figs. 2 and 3). For the Western blot assay, we incubated V5-tagged human LPL with CHO-K1 cells expressing wild-type or mutant versions of an S-protein-tagged GPIHBP1. After 2 h, the cells were washed, and the amount of cell surface-bound LPL was quantified by Western blotting (Fig. 2). Cells expressing wild-type GPIHBP1 bound LPL avidly, and this binding was significantly reduced with heparin (Fig. 2). In contrast, several GPIHBP1 mutants (e.g. L71A, L92A, I93A, H106L, S107A, or W109S) bound little if any LPL (Fig. 2). For each GPIHBP1 mutant, we quantified LPL, GPIHBP1, and actin signals and calculated the “LPL/GPIHBP1 ratio” after normalization to actin. The decrease in LPL binding for each mutant is compiled in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

Western blot assays to assess the ability of mutant GPIHBP1 proteins to bind LPL. CHO-K1 cells were electroporated with wild-type or mutant versions of S-protein-tagged GPIHBP1 constructs (or empty vector). After 24 h, the cells were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with V5-tagged human LPL with or without heparin (500 units/ml). After washing the cells, we performed Western blots of cell lysates with an anti-V5 antibody (to detect the amount of LPL bound to cells) and an anti-S-protein antibody (to detect GPIHBP1 expression). Actin was used as a loading control.

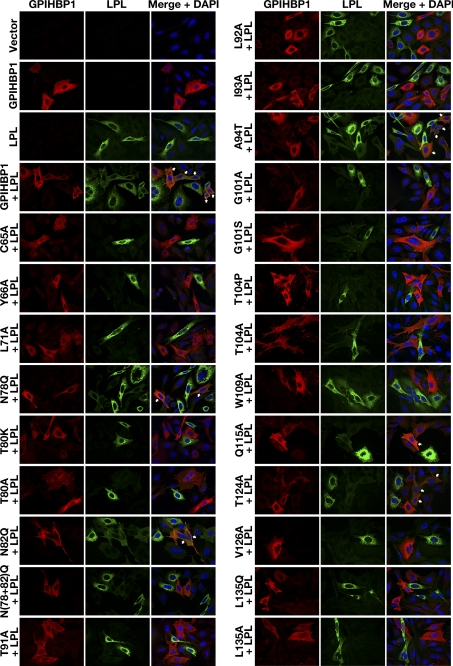

FIGURE 3.

An immunofluorescence microscopy assay to assess the ability of mutant GPIHBP1 proteins to bind LPL. CHO-K1 cells transfected with a wild-type or a mutant GPIHBP1 construct (S-protein-tagged) were mixed with cells that had been transfected with a plasmid encoding V5-tagged human LPL. The mixture of cells was then plated on a coverslip and incubated at 37 °C. After 16 h, the cells were stained with a goat antiserum against the S-protein tag (red) and a mouse monoclonal antibody against the V5 tag (green). Cell nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue). Cells expressing wild-type GPIHBP1 captured LPL secreted by the neighboring LPL-expressing cells; hence, the GPIHBP1 and LPL signals colocalized in the merged image (arrows). Some mutant GPIHBP1 proteins (C65A, Y66A, L71A, T80K, T80A, T91A, L92A, I93A, G101A, G101S, T104P, T104A, W109A, V126A, L135Q, and L135A) bound little or no LPL; the cells expressing those mutant proteins had very little to no LPL on the cell surface, and there was no colocalization of GPIHBP1 and LPL in the merged image.

TABLE 1.

Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain to assess the importance of individual amino acid residues for LPL binding

The amount of LPL binding to GPIHBP1 was assessed by Western blotting (band intensities were quantified with a Li-Cor scanner). The ratio of the LPL signal to the GPIHBP1 signal was normalized to actin expression; the amount of LPL binding with each GPIHBP1 mutant was compared with the amount of LPL binding with wild-type GPIHBP1.

| Mutation | Decrease in LPL binding | Mutation | Decrease in LPL binding |

|---|---|---|---|

| C65A | ≥90% | T104A | 81% |

| Y66A | ≥90% | T104P | ≥90% |

| T67A | None | T105A | ≥90% |

| C68A | ≥90% | H106A | 58% |

| K69A | None | H106L | ≥90% |

| S70A | None | S107A | ≥90% |

| L71A | ≥90% | T108A | None |

| P72A | None | W109A | ≥90% |

| R73A | None | W109S | ≥90% |

| D74A | None | C110A | ≥90% |

| E75A | None | T111A | None |

| R76A | None | D112A | None |

| C77A | ≥90% | S113A | None |

| N78Q | 65% | C114A | ≥90% |

| L79A | None | Q115A | None |

| T80A | 29–80% | Q115P | ≥90% |

| T80K | ≥90% | P116A | None |

| Q81A | None | P116S | None |

| N82Q | None | I117A | None |

| C83A | ≥90% | I117T | None |

| S84A | None | T118A | None |

| H85A | None | K119A | None |

| G86A | None | T120A | None |

| Q87A | None | V121A | None |

| T88A | None | V121S | None |

| C89A | ≥90% | E122A | None |

| T90A | None | G123A | None |

| T91A | ≥90% | G123E | None |

| L92A | ≥90% | T124A | 76% |

| I93A | ≥90% | Q125A | None |

| I93S | ≥90% | V126A | ≥90% |

| A94T | 59–80% | T127A | None |

| H95A | None | M128A | None |

| G96A | None | T129A | None |

| N97A | None | C130A | ≥90% |

| T98A | None | C131A | ≥90% |

| E99A | None | Q132A | None |

| S100A | None | S133A | None |

| G101A | 72% | S134A | None |

| G101S | 70–90% | L135A | ≥90% |

| L102A | None | L135Q | 89% |

| L103A | 61% | C136A | ≥90% |

| L103P | 89% |

Binding of LPL to GPIHBP1 was also assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy. CHO cells expressing V5-tagged human LPL were mixed with CHO cells that expressed wild-type or mutant versions of GPIHBP1 and then plated together on a coverslip. After incubating the cells for 16 h at 37 °C, the cells were washed, fixed, permeabilized, and stained with V5 and S-protein antibodies (to detect LPL and GPIHBP1, respectively). Cells expressing wild-type GPIHBP1 captured LPL secreted by adjacent LPL-expressing cells, resulting in colocalization of the LPL and GPIHBP1 signals (Fig. 3). In contrast, some GPIHBP1 mutants (e.g. Y66A, T91A, G101A, T104A, W109A, and V126A) were unable to bind LPL; hence, no LPL was bound to GPIHBP1-expressing cells (Fig. 3). Results of the two assays were concordant; GPIHBP1 mutants that could not bind LPL in the Western blot assay exhibited little or no binding in the immunofluorescence microscopy assay.

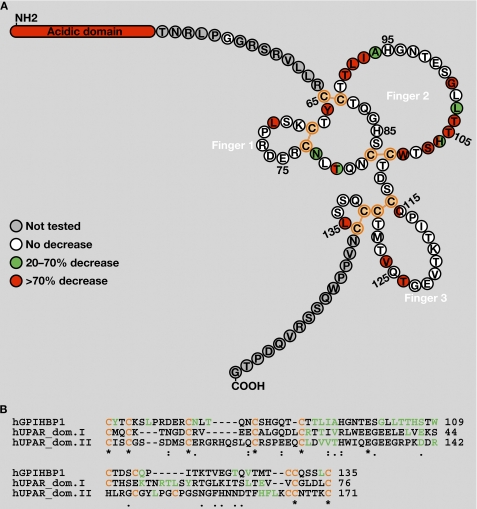

Mutations in any of the 10 cysteines in the GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain abolished LPL binding, in keeping with earlier findings (11). Also, several mutants with reduced trafficking to the cell surface-bound LPL poorly (T80A, T80K, A94T, T104P, T124A, L135A, and L135Q) (Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3). Aside from those residues, we identified 12 additional amino acids important for LPL binding (Tyr-66, Leu-71, Thr-91 to Ile-93, Gly-101 to Trp-109, and Val-126) (Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3). Most of the latter residues were concentrated within finger 2 of the GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain (Fig. 4A). Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of UPAR (a GPI-anchored protein with several Ly6 motifs) helped to define residues important for the ability of UPAR to bind its ligand urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) (12–14). Interestingly, many of the residues required for ligand binding were concentrated in finger 2 of the UPAR Ly6 motifs. Aside from the conserved cysteines, there is little homology between the Ly6 domains of GPIHBP1 and UPAR; nevertheless, the positions of amino acids important for the ability of GPIHBP1 to bind LPL are similar to the positions of residues important for the ability of UPAR to bind uPA (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Amino acid residues in the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 that are required for LPL binding. A, the amino acid sequence of GPIHBP1 from immediately after the acidic domain (Thr-51) to the GPI-anchoring site (Gly-151). This schematic illustrates the five disulfide bonds (orange) of GPIHBP1 and the three fingers of the Ly6 domain (based on the crystal structures of CD59 (22) and UPAR (14)). Replacement of amino acids highlighted in green with alanine led to a moderate reduction in LPL binding (20–70%), whereas replacement of residues highlighted in red resulted in a marked reduction in LPL binding (>70%). For a subset of residues, a second amino acid substitution (aside from alanine) was assessed (see Table 1). Residues highlighted with two colors indicate cases where the effect of the alanine substitution (on the right) differed from the effect of the other amino acid substitution (on the left). B, amino acid alignment of the Ly6 domain of human GPIHBP1 and the Ly6 domains I and II of human UPAR. Residues in green are required for the binding of GPIHBP1 to LPL or for the binding of UPAR to its ligand (uPA) (12–14). Cysteines are highlighted in orange.

In several cases, we tested the effects of a second amino acid substitution on the ability of GPIHBP1 to bind LPL. In most instances, the impact of the alanine substitution and the second amino acid substitution were similar (Fig. 4A). However, in one case, the effects of different amino acid substitutions were distinct. A Q115A mutation had little effect on LPL binding (Fig. 5), but a Q115P mutation reduced binding by ≥90%. Gln-115 is conserved in most mammalian species, but dogs have a Lys in that position, and platypus have a Glu (not conservative changes). Interestingly, replacing Gln-115 in human GPIHBP1 with Glu or Lys had little or no effect on LPL binding (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Assessing the effects of mutations of Gln-115 of GPIHBP1 on LPL binding. CHO-K1 cells were electroporated with wild-type GPIHBP1 or mutant GPIHBP1 proteins containing mutations of Gln-115 (Q114A, Q115E, Q115K, and Q115P). All constructs contained an S-protein tag. On the morning following the electroporation, the cells were incubated with V5-tagged human LPL (with or without heparin, 500 units/ml) for 2 h at 4 °C. After washing the cells, we performed Western blots of cell lysates with a V5-specific antibody (to assess binding of LPL to cells) and an antibody against the S-protein tag (to assess GPIHBP1 expression levels). Actin was used as a loading control.

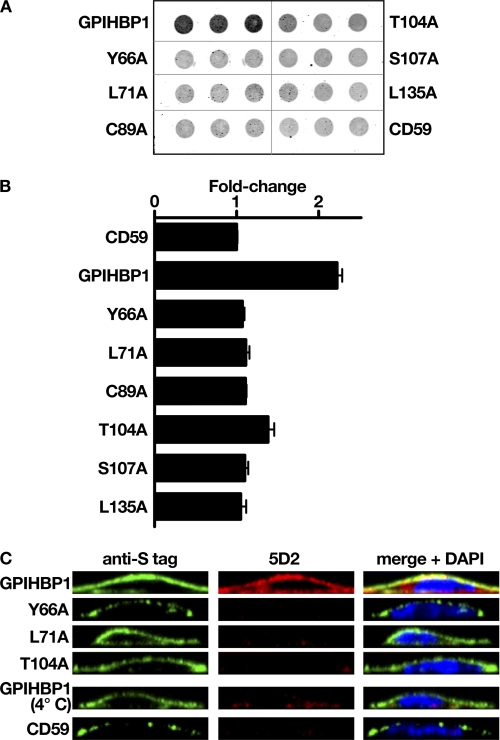

Assessing the Ability of GPIHBP1 Mutants to Transport LPL across Endothelial Cells

We suspected that mutant GPIHBP1 proteins that lacked the capacity to bind LPL in the CHO cell-based assays would also lack the ability to transport LPL across endothelial cells. To test this idea, we transfected RHMVECs with either wild-type or mutant GPIHBP1 constructs and grew the cells to confluence on transwell filters (1). Human LPL was added to the basolateral side of the filter, and the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The LPL that was transported to the apical surface was released with heparin, and the LPL in the apical medium was quantified with the Li-Cor infrared scanner (Fig. 6A). We then plotted the amount of LPL transport in cells expressing wild-type GPIHBP1, a series of mutant GPIHBP1 proteins, and CD59 (an unrelated Ly6 protein that cannot bind LPL) (Fig. 6B). As predicted, GPIHBP1 mutants that could not bind LPL in the Western blot and immunofluorescence microscopy assays were unable to transport LPL across endothelial cells (Fig. 6). LPL transport across GPIHBP1-expressing endothelial cell monolayers was also assessed by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 6C). In these studies, LPL was added to the basolateral medium of endothelial cells and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After washing the cells, antibodies against GPIHBP1 and LPL were added to the apical medium and the basolateral medium. In endothelial cells expressing wild-type GPIHBP1, LPL could be detected at the apical surface of cells (Fig. 6C). When the same cells were incubated at 4 °C, no transport of LPL to the apical surface of cells occurred (Fig. 6C). LPL was also not transported to the apical surface of CD59-expressing endothelial cells. When endothelial cells expressed a mutant GPIHBP1 that lacked the ability to bind LPL in CHO cell-based assays, there was no transport of LPL to the apical surface (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Testing the ability of mutant GPIHBP1 proteins to transport LPL across endothelial cells. RHMVECs were electroporated with plasmids encoding wild-type or mutant versions of GPIHBP1 or human CD59. All constructs contained an S-protein tag. Cells were plated on transwell filters (1) and grown to confluence. Human LPL was added to the basolateral chamber, and the ability of the transfected cells to transport LPL to the apical surface was assessed by dot blotting (A and B) or immunofluorescence microscopy (C). A, dot blot to assess the amount of LPL that was releasable from the apical surface of cells with heparin. For these studies, LPL was added to the basolateral chamber, and the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Heparin (100 units/ml) was then added to the apical chamber, and the amount of heparin-releasable LPL was assessed by dot blots with monoclonal antibody 5D2 (a gift from Dr. John Brunzell (University of Washington School of Medicine)). Antibody binding was quantified with a Li-Cor scanner. B, bar graph showing the -fold change in LPL transport (mean ± S.E. (error bars)) by GPIHBP1-transfected cells relative to CD59-transfected cells (set as 1.0). C, immunofluorescence microscopy was used to assess the ability of GPIHBP1 proteins and CD59 to transport LPL to the apical face of RHMVECs. LPL was added to the basolateral chamber of endothelial cells grown on transwell filters. After incubating the cells for 2 h at 37 °C, the cells were washed and incubated with a goat polyclonal antibody against the S-protein tag (to detect GPIHBP1 or CD59) and monoclonal antibody 5D2 (to detect LPL). (The antibodies were added to both basolateral and apical chambers.) After incubations with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies, the filters were removed and mounted onto coverslips for imaging by epifluorescence microscopy.

DISCUSSION

GPIHBP1 is the endothelial cell protein that binds and transports LPL from the subendothelial spaces to the capillary lumen, where it hydrolyzes triglycerides in the plasma lipoproteins. GPIHBP1 is a three-fingered Ly6 protein that is unique in having a strongly acidic domain at its amino terminus. A previous study showed that the acidic domain is required for LPL binding (7). The involvement of the acidic domain makes sense because LPL contains several heparin-binding domains enriched in lysines and arginines (4–6). However, several recent studies, including the discovery of chylomicronemia patients with missense mutations in the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 (15–17), have suggested that the acidic domain is not the sole determinant of LPL binding. In the current study, we used alanine-scanning mutagenesis to investigate the notion that the GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain is crucial for LPL binding. We identified 18 amino acids in the Ly6 domain that, when replaced with Ala, reduced LPL binding. Six reduced the expression of GPIHBP1 on the cell surface, whereas the other 12 reduced LPL binding without significantly affecting GPIHBP1 expression levels on the cell surface. The latter residues were found in all three fingers of the Ly6 domain but were concentrated in finger 2, the most conserved region of the protein (18). It seems likely that this region interacts directly with LPL. Lending credence to this idea is the observation that the corresponding amino acids in finger 2 of the UPAR Ly6 domains have been shown to interact directly with its ligand (uPA) both by alanine-scanning mutagenesis and crystallography (12–14). Also, it is noteworthy that some cases of mal de Meleda (an autosomal recessive palmarplantar keratoderma) are caused by a missense mutation (R71H) in finger 2 of SLURP1, another Ly6 protein (19).

The ability of each “alanine mutant” to bind LPL was assessed in two assays. We used immunofluorescence microscopy to determine if the mutant GPIHBP1s were capable of binding LPL secreted by adjacent LPL-transfected cells. The microscopy assay rapidly identified mutants that lacked the ability to bind LPL. To quantify binding, we incubated GPIHBP1-expressing cells with LPL and measured LPL binding by Western blotting. The intensity of the LPL band was quantified with a Li-Cor scanner, normalized to actin, and compared with LPL binding in cells expressing wild-type GPIHBP1. All results were verified by three independent assays. For each mutant protein, the results from the two assays were concordant; whenever we observed markedly reduced binding by immunofluorescence microscopy, we observed a >90% reduction in LPL binding in the Western blot assay.

The essential function of GPIHBP1 is to transport LPL across capillary endothelial cells. We predicted that any mutation that abolished LPL binding in CHO cell-based assays would also block LPL movement across endothelial cells. Indeed, GPIHBP1 mutations that eliminated LPL binding in CHO cell assays (e.g. Y66A, L71A, T104A, S107A, T124A, and L135A) also prevented LPL transport across cultured endothelial cells, as judged by either immunofluorescence microscopy or by the amount of heparin-releasable LPL at the apical face of cells.

The finding that point mutations in the GPIHBP1 Ly6 domain could abolish LPL binding is consistent with genetic observations in humans with chylomicronemia (15–17, 20). Thus far, five missense mutations have been implicated in chylomicronemia, four of them missense mutations involving Cys-65 or Cys-68 and the fifth a Gln-to-Pro substitution at residue 115. All markedly reduced the ability of GPIHBP1 to bind LPL (15–17). The fact that the cysteine mutations would interfere with the LPL binding is not particularly surprising, given that the disulfide bonds are critical for generating the protein's three-fingered structural motif. We suspect that the Pro at residue 115 has similar consequences, by introducing a turn immediately adjacent to Cys-114. When Gln-115 was replaced with Lys or Glu, there was no detectable effect on LPL binding.

In addition to the conserved cysteines, Leu-135 appears to be important for GPIHBP1 function. Changing Leu-135 to Ala or Glu reduced expression of GPIHBP1 at the cell surface by >80%. Interestingly, Leu-135 is conserved across mammalian species. Moreover, the corresponding residue in SLURP1, CD59, and UPAR is also a leucine, and a missense mutation involving that leucine in SLURP1 causes mal de Meleda (21).

In summary, the current studies support the idea that the Ly6 domain of GPIHBP1 is crucial for the binding and transendothelial transport of LPL. However, as noted earlier, the Ly6 domain is not the only relevant feature; the acidic domain is also required (7). Understanding the precise roles of the acidic and Ly6 domains in LPL binding will ultimately require co-crystallization of the two proteins, but we suspect that both domains will turn out to have direct and additive roles in LPL binding.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL094732 (to A. P. B.), P01 HL090553 (to S. G. Y.), and R01 HL087228 (to S. G. Y.). This work was also supported by a Scientist Development Award from the American Heart Association, National Office (to A. P. B.).

- Ly6

- lymphocyte antigen 6

- GPI

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- LPL

- lipoprotein lipase

- UPAR

- urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor

- uPA

- urokinase plasminogen activator

- RHMVEC

- rat heart microvascular endothelial cell

- BisTris

- bis(2-hydroxyethyl)iminotris(hydroxymethyl)methane.

REFERENCES

- 1. Davies B. S., Beigneux A. P., Barnes R. H., 2nd, Tu Y., Gin P., Weinstein M. M., Nobumori C., Nyrén R., Goldberg I., Olivecrona G., Bensadoun A., Young S. G., Fong L. G. (2010) Cell Metab. 12, 42–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beigneux A. P., Davies B. S., Gin P., Weinstein M. M., Farber E., Qiao X., Peale F., Bunting S., Walzem R. L., Wong J. S., Blaner W. S., Ding Z. M., Melford K., Wongsiriroj N., Shu X., de Sauvage F., Ryan R. O., Fong L. G., Bensadoun A., Young S. G. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 279–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fry B. G., Wüster W., Kini R. M., Brusic V., Khan A., Venkataraman D., Rooney A. P. (2003) J. Mol. Evol. 57, 110–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ma Y., Henderson H. E., Liu M. S., Zhang H., Forsythe I. J., Clarke-Lewis I., Hayden M. R., Brunzell J. D. (1994) J. Lipid Res. 35, 2049–2059 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hata A., Ridinger D. N., Sutherland S., Emi M., Shuhua Z., Myers R. L., Ren K., Cheng T., Inoue I., Wilson D. E., Iverius P. H., Lalouel J. M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 8447–8457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sendak R. A., Bensadoun A. (1998) J. Lipid Res. 39, 1310–1315 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gin P., Yin L., Davies B. S., Weinstein M. M., Ryan R. O., Bensadoun A., Fong L. G., Young S. G., Beigneux A. P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29554–29562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cunningham B. C., Wells J. A. (1989) Science 244, 1081–1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gin P., Beigneux A. P., Davies B., Young M. F., Ryan R. O., Bensadoun A., Fong L. G., Young S. G. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1771, 1464–1468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Beigneux A. P., Gin P., Davies B. S., Weinstein M. M., Bensadoun A., Ryan R. O., Fong L. G., Young S. G. (2008) J. Lipid Res. 49, 1312–1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Beigneux A. P., Gin P., Davies B. S., Weinstein M. M., Bensadoun A., Fong L. G., Young S. G. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30240–30247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gårdsvoll H., Danø K., Ploug M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37995–38003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gårdsvoll H., Gilquin B., Le Du M. H., Ménèz A., Jørgensen T. J., Ploug M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19260–19272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Llinas P., Le Du M. H., Gårdsvoll H., Danø K., Ploug M., Gilquin B., Stura E. A., Ménez A. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1655–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beigneux A. P., Franssen R., Bensadoun A., Gin P., Melford K., Peter J., Walzem R. L., Weinstein M. M., Davies B. S., Kuivenhoven J. A., Kastelein J. J., Fong L. G., Dallinga-Thie G. M., Young S. G. (2009) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29, 956–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Franssen R., Young S. G., Peelman F., Hertecant J., Sierts J. A., Schimmel A. W., Bensadoun A., Kastelein J. J., Fong L. G., Dallinga-Thie G. M., Beigneux A. P. (2010) Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 169–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Olivecrona G., Ehrenborg E., Semb H., Makoveichuk E., Lindberg A., Hayden M. R., Gin P., Davies B. S., Weinstein M. M., Fong L. G., Beigneux A. P., Young S. G., Olivecrona T., Hernell O. (2010) J. Lipid Res. 51, 1535–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Young S. G., Davies B. S., Fong L. G., Gin P., Weinstein M. M., Bensadoun A., Beigneux A. P. (2007) Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 18, 389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Favre B., Plantard L., Aeschbach L., Brakch N., Christen-Zaech S., de Viragh P. A., Sergeant A., Huber M., Hohl D. (2007) J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coca-Prieto I., Kroupa O., Gonzalez-Santos P., Magne J., Olivecrona G., Ehrenborg E., Valdivielso P. (2011) J. Intern. Med., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yerebakan O., Hu G., Yilmaz E., Celebi J. T. (2003) Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 28, 542–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fletcher C. M., Harrison R. A., Lachmann P. J., Neuhaus D. (1994) Structure 2, 185–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]