Abstract

ric-8 (resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8) genes have positive roles in variegated G protein signaling pathways, including Gαq and Gαs regulation of neurotransmission, Gαi-dependent mitotic spindle positioning during (asymmetric) cell division, and Gαolf-dependent odorant receptor signaling. Mammalian Ric-8 activities are partitioned between two genes, ric-8A and ric-8B. Ric-8A is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Gαi/αq/α12/13 subunits. Ric-8B potentiated Gs signaling presumably as a Gαs-class GEF activator, but no demonstration has shown Ric-8B GEF activity. Here, two Ric-8B isoforms were purified and found to be Gα subunit GDP release factor/GEFs. In HeLa cells, full-length Ric-8B (Ric-8BFL) bound endogenously expressed Gαs and lesser amounts of Gαq and Gα13. Ric-8BFL stimulated guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) binding to these subunits and Gαolf, whereas the Ric-8BΔ9 isoform stimulated Gαs short GTPγS binding only. Michaelis-Menten experiments showed that Ric-8BFL elevated the Vmax of Gαs steady state GTP hydrolysis and the apparent Km values of GTP binding to Gαs from ∼385 nm to an estimated value of ∼42 μm. Directionality of the Ric-8BFL-catalyzed Gαs exchange reaction was GTP-dependent. At sub-Km GTP, Ric-BFL was inhibitory to exchange despite being a rapid GDP release accelerator. Ric-8BFL binds nucleotide-free Gαs tightly, and near-Km GTP levels were required to dissociate the Ric-8B·Gα nucleotide-free intermediate to release free Ric-8B and Gα-GTP. Ric-8BFL-catalyzed nucleotide exchange probably proceeds in the forward direction to produce Gα-GTP in cells.

Keywords: Enzyme Catalysis, G Proteins, Protein Purification, Protein-Protein Interactions, Signal Transduction, GDP Release Factor, Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor, Ric-8A, Ric-8B

Introduction

Heterotrimeric G proteins transduce signals received from ligand-bound G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)2 to intracellular effector enzymes. Agonist-bound GPCRs activate coupled G protein heterotrimers by accelerating the rate of GDP for GTP exchange on the Gα subunit (1). The understanding of G protein signaling pathway complexity expanded beyond this traditional paradigm when modulatory proteins that regulate G protein activation apart from receptors were uncovered and characterized (2–7).

One well characterized non-receptor G protein activator is Ric-8 (resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8A). ric-8 was first identified in a genetic screen devised to find mutants of genes that positively regulated Caenorhabditis elegans neurotransmission (8). Through genetic epistasis analyses, it was predicted that ric-8 action was elicited upstream of Gαq and/or Gαs to regulate divergent G protein signaling outputs (8–10). Ric-8 was first linked physically to G proteins when two homologous mammalian Ric-8 proteins (so-named Ric-8A and Ric-8B) were isolated in yeast two hybrid screens using Gαo and Gαs baits, respectively. Ric-8A interacted with Gαi/o, Gαq, and Gα13 subunits (7). Ric-8B interacted with Gαs and Gαq (7, 11). Evidence of a preferred interaction of Ric-8A with Gαi-GDP led to experimentation showing that Ric-8A was a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the monomeric Gα subunits it bound in vitro. Purified Ric-8A stimulated intrinsic Gα GDP release, leading to accelerated GTP binding kinetics and steady state GTPase activity (7, 12).

Technical issues of Ric-8B protein purification have prevented an examination of its putative Gα GEF activity. Based on its yeast two-hybrid Gα binding preferences, we hypothesized that Ric-8B was a GEF for Gαs- and/or Gαq-class subunits. Evidence in support of this has since been provided by demonstration that full-length Ric-8B (Ric-8BFL) positively influenced Gs-class signaling in cells. Ric-8BFL overexpression potentiated ligand-dependent GPCR activation of Golf- and Gs-dependent cAMP production (13, 14). A shorter expressed isoform of Ric-8B that lacks the entirety of the region encoded by exon 9 of Ric-8BFL (termed Ric-8BΔ9) did not enhance Golf signaling and actually appeared to be a modest inhibitor. Interestingly, Ric-8BFL is one of the long sought components required to reconstitute odorant receptor signaling in heterologous systems (14–17). Ric-8BFL overexpression in HEK cells with odorant receptors and receptor co-factors promoted odorant- and Golf-dependent cAMP accumulation. Despite these findings, no direct demonstration that Ric-8B is a Gα GEF has been made, and the role that Ric-8B might have in positively regulating Gs-class signaling has not been elucidated.

An idea not intuitively consistent with Ric-8B-GEF-mediated support of Gαs-class signaling outputs was provided from studies showing that ric-8 may control G protein expression. Genetic ablation of the single C. elegans or Drosophila melanogaster ric-8 gene reduced levels of plasma membrane-associated Gαi and Gβ subunits (18–21). RNAi disruption of ric-8B in NIH-3T3 cells reduced Gαs steady state expression, and some of the remaining Gαs was marked for ubiquitin-mediated degradation (22). Ric-8A and Ric-8B greatly potentiated co-expressed recombinant Gα subunit levels in insect cells (23). These findings raise the possibility that Ric-8B may not potentiate adenylyl cyclase signaling as a direct Gs/Golf GEF signaling activator but may do so by supporting Gαolf (or enhancing Gαs) plasma membrane expression in systems, such as HEK cells, where Gαolf is not normally expressed. These ideas necessitated experimentation to address directly whether Ric-8B is a GEF activator of Gα subunits and to determine its mechanism of action.

Here we show by direct biochemical demonstration that Ric-8BFL is a Gα GDP release factor (GRF) and GEF for Gαs and Gαolf, Gαq, and, Gα13. Ric-8BΔ9 is a Gαs-specific GRF/GEF but was actually a modest inhibitor of Gαolf GTPγS binding. A stringent correlation was observed between Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A binding to endogenously expressed Gα subunits in cells with respective Ric-8 protein capacity to support Gα nucleotide release and exchange in vitro. GTP titration experiments indicate that Ric-8B would act as a directional GEF in cells to promote formation of Gαs-GTP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids, Antibodies, and Reagents

To create ric-8B baculovirus donor constructs, mouse Ric-8BFL (Invitrogen, LLAM collection, clone 6490136) and rat Ric-8BΔ9 splice form cDNAs were subcloned by PCR into pFastBacGSTTEV (7). To create tandem affinity purification (TAP)-tagged ric-8 constructs, a triple FLAG tag was inserted by PCR between the TEV-protease cleavage site and the Ric-8 coding sequences in the pFASTBacGSTTEV ric-8 vectors (A and BFL). TAP-tagged ric-8 cDNAs were excised with SalI and NotI restriction enzymes and subcloned into those sites in pFB Hygro (a gift from the Alliance for Cell Signaling). G protein subunit-specific antisera were used to detect Gαi1/2 (BO84) (24), Gαq (WO82) (25), Gαq/11 (C19) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), Gα13 (A20) (Santa Cruz), Gαs (584) (26), Gβ1/2 (U49) (24), and Gβ1–4 (B600) (24). [35S]GTPγS, [α-32P]GTP, and [γ-32P]GTP were purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences.

Purification of Recombinant Proteins

Gαs short and Gβ1γ2 were purified as described (27–29). Gαolf, Gαq, and Gα13 were purified from insect cell detergent lysates using a Ric-8 association technique as described (23). Ric-8A was purified as described (7, 30). GST-tagged ric-8B baculoviruses were produced and amplified according to the manufacturer's instructions using the Bac-to-Bac Sf9 cell expression system (Invitrogen). Hi5 insect cells were grown in Sf900II medium to a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml and infected with amplified GST-ric-8B baculoviruses for 48 h. Cells were collected and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, protease inhibitor mixture (23 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 21 μg/ml Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine-chloromethyl ketone, 21 μg/ml l-1-p-tosylamino-2-phenylethyl-chloromethyl ketone, 3.3 μg/ml leupeptin, and 3.3 μg/ml lima bean trypsin inhibitor)) (Sigma-Aldrich) by nitrogen cavitation using a Parr Bomb (Parr Instrument Co., Moline, IL). Lysates were centrifuged sequentially at 3000 × g and at 100,000 × g for 45 min. The final supernatant was adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare). The resin was washed with lysis buffer and incubated with TEV protease for 16 h at 4 °C. Released Ric-8B proteins were bound to a 5-ml Hi-trap Q column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a linear salt gradient from 100 to 500 mm NaCl. Monomeric Ric-8B proteins were separated from Ric-8B multimers by Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel filtration chromatography (GE Healthcare). Intact GST-TEV-Ric-8 proteins were eluted from glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin with lysis buffer containing 20 mm reduced glutathione. GST-TEV-Ric-8B fusion proteins were purified using successive Hi-trap Q and Superdex gel filtration chromatographies.

Protein Interaction Assays

GST-Ric-8 fusion proteins (500 nm) were incubated with purified Gα (1 μm) or Gα (1 μm) and Gβ1γ2 (1 μm) for 30 min at 22 °C in incubation buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.05% (m/v) deionized polyoxyethylene 10 lauryl ether (C12E10), and 1 μm GDP). Protein mixtures were then incubated with 20 μl of glutathione-Sepharose 4B for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed with incubation buffer, and Ric-8 or Ric-8-bound proteins were released by digestion with AcTEV protease (Invitrogen) for 16 h at 4 °C, processed in reducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

GST-Ric-8 interactions with G proteins extracted from brain membranes with detergents were performed as described previously with more sensitive Western blotting conditions (7). Rat brain membrane extracts were prepared by homogenizing whole rat brains in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 11% sucrose, and protease inhibitor mixture using a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g, and membrane pellets were pooled and homogenized in extraction buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT) before the addition of 1% (m/v) C12E10 and 10 μm GDP to solubilize membranes for 1 h at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g, and the detergent-protein extract supernatant was collected. GST-Ric-8BFL, GST-Ric-8BΔ9, GST-Ric-8A, or GST protein (100 μg of each) was adsorbed to a 60-μl bed volume of glutathione-Sepharose 4B pre-equilibrated in equilibration buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, and protease inhibitor mixture) for 2 h at 4 °C. The resins were collected by centrifugation at 500 × g and washed twice with 1 ml of equilibration buffer. Detergent protein extract (11.4 mg) was then incubated with affinity and control resins for 2 h at 4 °C. The resins were collected by centrifugation, washed five times with extraction buffer, and incubated with 45 μl of extraction buffer containing 5 μl of AcTEV protease (Invitrogen) for 16 h at 4 °C. The resins were pelleted, and the 50-μl supernatants were combined with a 70-μl subsequent resin wash. Eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose and Western blotted with G protein subunit-specific antisera.

Ric-8 Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) of G Proteins

Phoenix 293T cells were transfected with the TAP-tagged ric-8 pFB Hygro constructs, and recombinant retroviruses were produced according to the manufacturer's instructions (Orbigen, Inc., San Diego, CA). HeLa S3 cells (CCL-2.2, ATCC, Manassas, VA) were infected with the viruses, and stable expression of TAP ric-8A or ric-8BFL was selected with 400 μg/ml hygromycin B for 7 days. Stable TAP Ric-8 HeLa S3 cell lines were expanded and grown in suspension paddle culture in Ca2+-free minimum essential medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mm l-glutamine, 200 μg/ml hygromycin B, and 0.1% pluronic acid. Suspension cells (3 × 109) were recovered and lysed in 20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 2 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor mixture by Parr Bomb nitrogen cavitation. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 40 min, and the supernatants were applied to glutathione-Sepharose 4B. The Sepharose was washed with lysis buffer and incubated with TEV protease for 18 h at 4 °C. Proteins released by TEV digestion were diluted with 7 ml of PBS containing 1 mm EDTA and protease inhibitor mixture and batch-bound to 250 μl of anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h at 4 °C. The FLAG resin was washed with PBS, suspended in reducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and boiled for 5 min. The FLAG resin eluates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted for G protein subunits.

GTPγS Binding and Release Assays

Gα GTPγS binding assays were described previously (7, 31). Briefly, Gα (100 nm) was mixed with Ric-8 proteins (200 nm or as indicated otherwise) at 25 or 30 °C in GTPγS binding buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 4 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.05% (m/v) C12E10 (Gαi1, Gαs short, Gα13) or 0.05% Genapol C-100 (Gαq, Gαolf)), and 10 μm [35S]GTPγS (SA 10,000 cpm/pmol). Triplicate aliquots were taken from the reactions at the indicated time points, quenched in GTP quench buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.7, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm GTP, and 0.08% (m/v) C12E10), and filtered onto BA-85 nitrocellulose filters. The filters were washed (20 mm Tris, pH 7.7, 100 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2), dried, and subjected to scintillation counting. GTPγS release measurements were performed using the aforementioned nitrocellulose filter binding method, but Gαs short or Gαq was first preloaded to completion with [35S]GTPγS. Gαs short was simply incubated in GTPγS binding buffer for 30 min at 25 °C with 10 μm [35S]GTPγS (SA 10,000 cpm/pmol). Gαq (10 μm) was preloaded with 100 μm [35S]GTPγS (SA 5,000 cpm/pmol) in gel filtration buffer containing Ric-8A catalyst (5 μm) for 18 h at 4 °C and 10 min at 25 °C. Gαq-GTPγS was then separated from Ric-8A by gel filtration as described (7, 30). GTPγS release from Gαs short or Gαq (100 nm) was initiated at 25 °C or 30 °C, respectively, by the addition of Ric-8 protein (500 nm) and challenge with 100 μm non-radioactive GTPγS. Free Mg2+ at 1 mm was used in the Gαq experiments to accelerate the observed rate of GTPγS release.

GDP Release Assay

Gα GDP release assays were described previously (12). Gα (100 nm) was loaded with 10 μm [α-32P]GDP (SA 50,000 cpm/pmol) for 1 h at 30 °C in 50 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 0.5 mm DTT, 5 mm EDTA, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 4% glycerol, and 0.05% (m/v) C12E10. GDP release was initiated at 25 °C upon the addition of Ric-8 proteins (0 or 200 nm) in reaction buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 1 mm DTT, 2 mm MgCl2, 100 mm NaCl, and 100 μm GTPγS). Duplicate aliquots were taken from the reactions at the indicated time points; quenched in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.7, 100 mm NaCl, 30 mm MgCl2, 30 μm AlCl3, 5 mm NaF, 50 μm GDP; and filtered onto BA-85 nitrocellulose filters. The filters were washed with AlF4−-containing quench buffer, dried, and subjected to scintillation counting.

Steady State GTP Hydrolysis (GTPase)

Ric-8 proteins (indicated concentrations) and Gα (50 nm) were mixed in buffer containing 20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 2 or 10 mm MgCl2, and 0.05% Genapol C100 (Gαq) or 0.05% (m/v) C12E10 (Gαs short). Triplicate reactions were started by the addition of 0.5–50 μm [γ-32P]GTP (SA ≥10,000 cpm/pmol) at 25 °C. Reactions were quenched with 5% Norit charcoal in 50 mm NaH2PO4, pH 3.0, and processed as described previously (32). The amount of hydrolyzed Pi was calculated after scintillation counting. In assays where 500 nm Gβ1γ2 was included, Gα plus Gβ1γ2 or Gα alone were preincubated for 15 min at 22 °C. Reactions were initiated by the addition of Ric-8 (500 nm) and 0.5 μm [γ-32P]GTP in reaction buffer.

Single Turnover GTPase

Gαs short-[γ-32P]GTP was prepared by limited modification of the method of Ross (32). Gαs short (5 μm) was incubated with 10 μm [γ-32P]GTP (SA 30,000 cpm/pmol) in Buffer C (50 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 5 μg/ml BSA, 0.05% (m/v) C12E10) containing 10 mm EDTA for 15 min at 25 °C. Gαs-[γ-32P]GTP was separated from free [γ-32P]GTP over a G25-Sephadex column (fine grade). Fractions containing Gα-[γ-32P]GTP were pooled and diluted to ∼50 nm in Buffer C containing 10 mm EDTA, 3 μg/ml BSA, and 1 μm GTP. Single-turnover GTPase reactions were started by the addition of 88 mm MgCl2 and Ric-8 (0 or 500 nm) at 4 °C. Aliquots from the reactions were taken at the indicated times and processed as described above for steady state GTPase.

Gel Filtration Assays

Ric-8B proteins (5 μm) were incubated with Gαs short (10 μm) or Gαq (10 μm) in gel filtration buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 3 mm DTT, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA) and 100 μm GDP or [35S]GTPγS (SA 35,000 cpm/pmol) for 15 min at 25 °C. The reactions were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were resolved over Superdex 75 and 200 10/300 GL columns arranged in series (GE Healthcare). Column eluates were fractionated, and fractions were subjected to Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and scintillation counting to measure GTPγS.

RESULTS

Ric-8 and G Protein Interactions

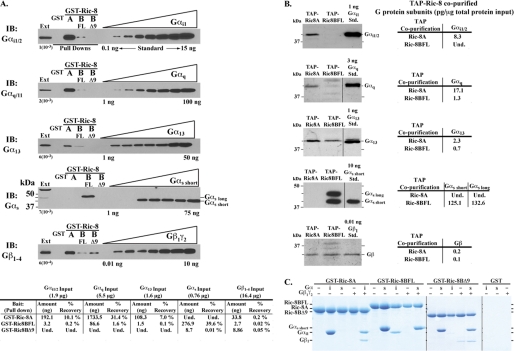

Individual interactions between G protein subunits and Ric-8B or Ric-8A have been described (7, 11, 13, 22, 33). However, a complete and comparative profile of the interactions between Ric-8BFL, Ric-8BΔ9, and Ric-8A with representatives of all four classes of Gα subunits or Gβγ has not been made. We tested Ric-8B and Ric-8A binding to G proteins expressed endogenously in cells and in vitro using membrane detergent extracts and purified components. Purified GST-TEV-Ric-8 fusion proteins or GST were adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose and incubated with detergent extracts of rat brain membranes. The resins were washed, and G proteins bound specifically were released by TEV protease digestion and identified by quantitative Western blot (Fig. 1A). Purified G protein subunit standards were used to calibrate the Western blot signals (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S2). No G proteins were recovered with control GST resin. Ric-8BFL bound members of all four Gα classes, but significantly more Gαs was recovered (39.6% of the total Gαs input versus 1.6% or less for other Gα subunits). Ric-8BΔ9 bound very low levels of Gαs exclusively (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S3). Ric-8A bound appreciable Gαq/11, Gαi1/2, and Gα13 (31.4, 10.1, and 7.0% of the input, respectively) but did not bind Gαs. Ric-8B was reported to interact with Gγ subunits by a yeast two-hybrid assay and overexpression/co-immunoprecipitation (33). Sensitive immunoblotting with an anti-Gβ1–4 common antibody revealed that Gβs (and presumably Gγs) were recovered at very low levels, albeit specifically by all three GST-Ric-8 proteins from the membrane detergent extracts (≤0.2% of input).

FIGURE 1.

Ric-8A and Ric-8B bind different sets of G protein subunits. A, whole rat brain membrane detergent extracts (11.4 mg) were incubated with 100 μg of purified GST-TEV, GST-TEV-Ric-8A, GST-TEV-Ric-8BFL, or GST-TEV-Ric-8BΔ9 proteins and applied to glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin. The resins were washed, and bound proteins were released by TEV protease digestion. Detergent extract input material (Ext.), the proteins released by TEV digestion, and increasing concentrations of purified G protein subunit standards (Gαi1, Gαq, Gα13, Gαs short, Gβ1γ2) were resolved by SDS-PAGE. The gels were transferred to nitrocellulose and Western blotted with G protein subunit-specific antisera as indicated. Immunoblot (IB) signals were calibrated by densitometry analysis in supplemental Fig. S2. The total amount of G protein isolated with each GST-Ric-8 bait is reported in ng and as percentage recovery of input. B, TAP-tagged Ric-8A or Ric-8BFL were stably expressed in HeLa S3 cells and purified from soluble (detergent-free) cell lysates by tandem affinity chromatography (glutathione-Sepharose 4B and FLAG affinity resins). Eluates from the FLAG affinity column and the indicated amounts of purified G protein subunit standards were resolved by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with G protein subunit-specific antisera. The amount of each G protein subunit (pg/μg of input) that co-purified with TAP-tagged Ric-8A or Ric-8BFL was measured by quantitative densitometry analysis of the immunoblots. C, purified GST-TEV-Ric-8 proteins (500 nm) were incubated with purified Gαi1 or Gαs short, with or without Gβ1γ2 (1 μm). The protein mixtures were adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin. The resins were washed, and proteins bound specifically were released by TEV protease digestion. The released proteins were processed in reducing SDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

A TAP strategy was used to investigate the complete profile of interactions between TAP-tagged Ric-8 proteins and endogenously expressed cytosolic G protein subunits using a single approach (Fig. 1B). HeLa S3 cell lines were created that stably expressed TAP-tagged Ric-8A or TAP-tagged Ric-8BFL. The TAP-tagged Ric-8 versions were expressed ∼6–8-fold higher than endogenous Ric-8A or Ric-8BFL (data not shown). Soluble (cytosolic) fractions of native lysates were prepared from these cell lines and purified successively by the two TAP affinity steps (glutathione-Sepharose and anti-FLAG affinity chromatography). Gα subunits recovered from the FLAG affinity resin were identified by quantitative Western blot using G protein subunit-specific immunoreagents (Fig. 1B). Ric-8BFL bound the long and short isoforms of Gαs selectively. No Gαs was bound to Ric-8A in cells. Ric-8A bound Gαi1/2 selectively. No Gαi1/2 was bound to Ric-8BFL in cells. 17-Fold more Gαq and 3-fold more Gα13 were co-purified with Ric-8A compared with the amounts co-purified with Ric-8BFL. Very low amounts of total Gβ co-purified with Ric-8A or Ric-8BFL from the soluble lysates. These results define the subsets of G protein subunits that Ric-8A and Ric-8BFL interact with in the cell and demonstrate that one subcellular site of these interactions is the cytosol.

To examine the observed specificity of the Ric-8B and Gαs or the Ric-8A and Gαi interaction and to discriminate whether Ric-8 proteins bind Gβγ and/or G protein trimers directly, GST-Ric-8 pull-down experiments were conducted using purified components with conditions that were probably well above the Kd values for relevant Ric-8-Gα subunit interactions (500 nm Ric-8A and 1 μm G protein subunits) (Fig. 1C). Ric-8A bound Gαi1 and Gi trimer but did not bind Gαs short or Gβ1γ2 alone. Ric-8BFL bound Gαs short and substoichiometric Gαi1 but did not show appreciable binding to the Gs short trimer or Gβ1γ2 alone. In contrast, Ric-8BΔ9 bound Gαs short, Gβ1γ2 alone, and perhaps Gs short trimer but did not bind Gαi1.

Ric-8B Is a G Protein α Subunit GEF

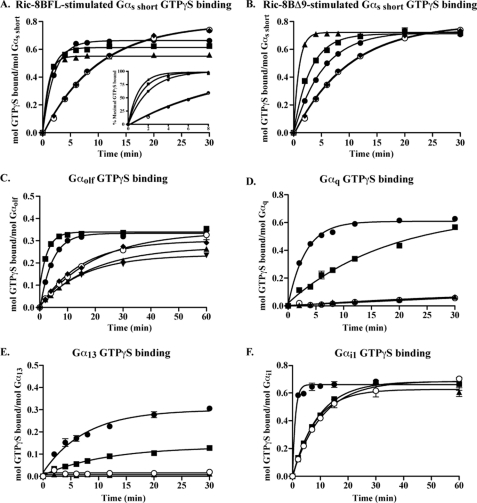

Ric-8B was proposed to be a GEF for Gαs- and Gαq-class subunits because of its homology to Ric-8A and abilities to bind these subunits and positively regulate Gs/Golf-induced cAMP accumulation in cells (Fig. 1) (7, 11, 13, 33). However, the mechanism of Ric-8B regulation of G protein signaling is not clear, and no positive result demonstrating Ric-8B GEF activity has been observed. A procedure was developed to purify active Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 from insect cells for the purpose of measuring putative Ric-8B GEF activities. Representatives of all four Gα subunit families (Gαs short and Gαolf, Gαq, Gα13, and Gαi1, 100 nm each) were incubated in timed GTPγS binding reactions alone or with purified Ric-8BFL, Ric-8BΔ9, or Ric-8A (200 nm each or doses as indicated). The amount of [35S]GTPγS bound to Gα over time was measured using a nitrocellulose filter-binding assay (7, 31). The purity and use of proteins in these and subsequent studies are shown and denoted in supplemental Fig. S1. Gαs short or Gαs short in the presence of Ric-8A bound GTPγS at a rate of 0.1 min−1, consistent with a previous report (34). Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 (200 nm each) increased this rate to 0.48 and 0.19 min−1, respectively (Fig. 2, A and B). Inclusion of increasing doses of Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 (200 nm to 2 μm each) in the Gαs short GTPγS binding reactions resulted in distinct effects. Both Ric-8B isoforms increased the Gαs short GTPγS binding rate in a dose-dependent manner (0.48–0.96 min−1 (Ric-8BFL) and 0.19–1.1 min−1 (Ric-8BΔ9)). However, Ric-8BFL uniquely lowered the Ymax of GTPγS binding (end point stoichiometry) from 0.66 to 0.56 mol of GTPγS/mol of Gαs short (at 200 nm to 2 μm Ric-8BFL).

FIGURE 2.

Ric-8BFL is a Gαq, Gα13, and Gαs/Gαolf GEF, and Ric-8BΔ9 is a Gαs GEF. The kinetics of GTPγS binding to Gαs short (A and B), Gαolf (C), Gαq (D), Gα13 (E), and Gαi1 (F) were measured in the absence (○) or presence of Ric-8 proteins (closed symbols). Purified G proteins (100 nm each) were added to reactions containing 10 μm [35S]GTPγS (SA 10,000 cpm/pmol) and the following purified Ric-8 proteins: 200 nm (●), 500 nm (■), and 2 μm (▴) Ric-8BFL or Ric-8BΔ9 or 200 nm Ric-8A (♦) (A and B); 200 nm Ric-8BFL (●), Ric-8BΔ9 (▴), or Ric-8A (♦) or 1 μm Ric-8BFL (■) or Ric-8BΔ9 (▾) (C); 200 nm Ric-8BFL (■), Ric-8BΔ9 (▴), or Ric-8A (●) (D–F). The reactions were incubated at 25 °C (30 °C for Gαi1) for the indicated times. Triplicate aliquots were withdrawn from the reactions, quenched, and filtered through nitrocellulose filters. The filters were washed, dried, and subjected to scintillation counting to quantify the amount of G protein-bound GTPγS at each time point. The data were fit to exponential one-phase association functions or linear regression using GraphPad Prism version 5.0. Results are presented as the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three experiments. A (inset), each data set was plotted as the percentage of maximal GTPγS bound to show that Ric-8BFL stimulated the rate of observed Gαs short GTPγS binding with increasing Ric-8BFL concentration. Notes that most error bars are smaller than actual plotted symbols. Intrinsic Gα rates (○) were measured in each experiment, although these points were often hidden by other data.

The inhibitory effects of Ric-8BFL on Gαs end point GTPγS binding were unusual. End point (Ymax) Gαs short and Gαq GTPγS binding were compared directly over a wide range of Ric-8 protein concentrations (supplemental Fig. S4). Ric-8BFL dose-dependently inhibited end point Gαs short GTPγS binding but increased Gαq GTPγS binding. Ric-8BΔ9 did not affect either G protein, and lower doses of Ric-8A (200 nm) resulted in saturated Gαq GTPγS binding. One possible explanation for the observed Ric-8BFL-dependent loss of end point Gαs short GTPγS binding was that Ric-8BFL caused irreversible denaturation of a portion of Gαs short over the course of the assay. To test this possibility, Ric-8BFL or Ric-8BΔ9 (5 μm each) was incubated with Gαs short-GTPγS (10 μm) for 30 min at 25 °C. The protein mixtures were gel-filtered to separate monomeric G proteins from G protein·Ric-8B dimeric complexes and higher ordered aggregates (supplemental Fig. S5). Virtually all of the Gαs short-GTPγS was recovered as active monomer or in complex with Ric-8BFL. Ric-8BFL did not cause Gαs short denaturation and aggregation. Ric-8BΔ9 itself was prone to aggregation, but the released Gαs short-GTPγS present in this reaction was not.

We recently reported the primary GTP binding characteristics and adenylyl cyclase activating activities of purified olfactory/brain-specific Gαs homolog, Gαolf (23). Ric-8BFL stimulated the Gαolf GTPγS binding rate in a dose-dependent manner, whereas Ric-8BΔ9 was actually a modest inhibitor of both end point Gαolf GTPγS binding stoichiometry and the GTPγS binding rate (Fig. 2C). Ric-8A did not affect GTPγS binding characteristics of Gαolf.

Gαq and Gα13 bind GTPγS negligibly in detergent solution (Fig. 2, D and E) (35, 36). Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A dramatically increased the Gαq GTPγS binding rate from negligible values to 0.06 min−1 and 0.31 min−1, respectively (Fig. 2D), and increased the negligible Gα13 GTPγS binding rate to 0.09 min−1 and 0.13 min−1, respectively (Fig. 2E). Ric-8BΔ9 did not affect the kinetics of Gαq or Gα13 GTPγS binding, consistent with the observation that Ric-8BΔ9 did not bind either Gα subunit. A small amount of Gαi1 (0.2% of input) was recovered by Ric-8BFL from the membrane extracts (Fig. 1A), but Ric-8BFL did not stimulate Gαi1 GTPγS binding. Conversely, Ric-8A bound substantial Gαi1/2 and stimulated Gαi1 GTPγS binding dramatically (Fig. 2F), as shown previously (7).

Ric-8B Is a GRF

G protein nucleotide exchange is limited by the slow GDP release step and followed by rapid GTP binding to the open form of Gα (37). GEFs stimulate GDP release. Ric-8-stimulated Gα GDP release measurements were made and compared directly to the corresponding rates of observed Gα GTPγS binding at equivalent Ric-8 concentrations. Intrinsic Gαs short GDP release (plotted as the inverse) and GTPγS binding rates were nearly equivalent (0.1 min−1 each; Fig. 3A), as were the Ric-8A-stimulated Gαi1 GDP release and GTPγS binding rates (0.13 and 0.14 min−1, respectively; Fig. 3B). However, Ric-8BFL- or Ric-8BΔ9-stimulated Gαs short GDP release rates (1.41 and 2.98 min−1, respectively) were markedly faster than the corresponding stimulated Gαs short GTPγS binding rates (0.48 and 0.19 min−1, respectively; Fig. 3, C and D). At the concentration of GTPγS used in these assays (10 μm), Ric-8B proteins were more effective Gαs GRFs than GEFs.

FIGURE 3.

Ric-8B delayed GTPγS binding to nucleotide-free Gαs after stimulating rapid GDP release. Purified Gαs short or myristoylated Gαi1 (100 nm each) was loaded to completion with 10 μm [α-32P]GDP (SA 50,000 cpm/pmol) and then added to reactions with or without purified Ric-8 proteins as indicated. Gα GDP release was measured at 25 °C by quenching aliquots of each reaction in AlF4−-containing buffer and filtering them onto nitrocellulose filters. The filters were washed, dried, and subjected to scintillation counting to quantify the amount of GDP that remained bound to Gα at each time point. The inverse of the percentage of maximal GDP release (■) was co-plotted with the percentage of maximal Ric-8-stimulated (●) or intrinsic (○) GTPγS binding (at 25 °C) over time for Gαs short alone (A), Gαi1 and Ric-8A (B), Gαs short and Ric-8BFL (C), or Gαs short and Ric-8BΔ9 (D). The data were fit to exponential one-phase association functions using GraphPad Prism version 5.0. All assay results are representative of at least three independent experiments that contained 2–3 replicates/assay.

Ric-8B-influenced G Protein Steady State GTP Hydrolysis (GTPase) Activity

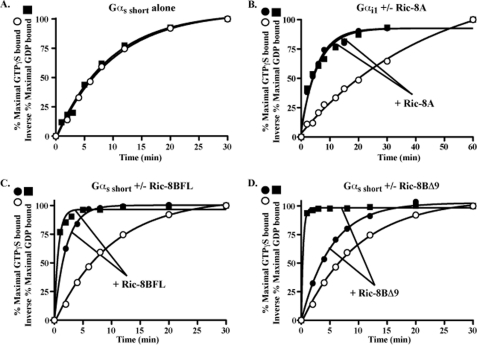

GTPγS binding to nucleotide-free Ric-8B·Gαs complexes was apparently slower than binding to nucleotide-free Gαs short. Steady state GTPase measurements were conducted to explore the mechanism of this kinetic delay. Because steady state GTPase is limited by GDP release, a GEF should enhance this rate (38). Surprisingly, at low GTP concentrations typically used in these assays (500 nm), Ric-8BFL potently inhibited Gαs short GTPase activity (IC50 ∼35 nm) (Fig. 4A). High concentrations of Ric-8BΔ9 increased Gαs short activity marginally, and Ric-8A had no effect. Conversely, at low GTP concentration, Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A stimulated the intrinsically low Gαq steady state GTPase activity to maximal velocities of 0.17 and 0.07 min−1, with estimated EC50 values of ∼150 and ∼110 nm, respectively (Fig. 4B). Ric-8BΔ9 did not affect Gαq steady state GTPase activity. A higher level of GTP (10 μm) was tested next to determine whether Ric-8 effects were dependent on GTP concentration. Interestingly, Ric-8BFL was no longer inhibitory but activated Gαs short GTPase activity weakly (Fig. 4C). High concentrations of Ric-8BΔ9 (250 nm to 2.5 μm) activated Gαs short with increasing efficacy and did not appear to be saturating even at the highest concentration tested. Ric-8-dependent Gαq activation was increased modestly at high GTP concentration, but a potency difference between Ric-8A and Ric-8BFL was revealed. Ric-8A and Ric-8BFL activated Gαq to similar maximal rates with EC50 values of ∼130 and ∼750 nm, respectively (Fig. 4D). Ric-8BΔ9 did not influence Gαq GTPase activity at any GTP concentration.

FIGURE 4.

Ric-8B regulation of Gαs short and Gαq steady state GTP hydrolytic activities are GTP-dependent. Gαs short (A, C, and E) or Gαq (B, D, and F) (50 nm each, total of 1 pmol/assay) was mixed in triplicate with Ric-8BFL (■), Ric-8BΔ9 (▴), or Ric-8A (●) (0–2.5 μm) and the indicated concentrations of [γ-32P]GTP (SA 10,000–70,000 cpm/pmol) to initiate steady state GTPase reactions at 25 °C. The reactions were quenched after 5–7 min in acidic charcoal suspension and processed as described. C, the Ric-8BΔ9 (△) preparation did not contain a contaminating GTPase. In the GTP titration experiments (E and F), Gα alone (○) or Gα and the indicated Ric-8 proteins (500 nm each, closed symbols) were used. All assay results are representative of at least three independent experiments that contained 3 replicates/assay. Error bars, S.E.

Quantitative analyses of Gαs short and Gαq steady state GTPase activities were performed by conducting GTP titrations. The data were plotted using Michaelis-Menten models to estimate the Km and Vmax values with or without Ric-8 proteins present. The calculated Km of Gαs short for GTP was 385.1 ± 10 nm, which was consistent with previous reports for Gα subunits (39, 40). Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 increased the Km dramatically to ∼42.4 ± 8.1 and ∼2.6 ± 0.2 μm, respectively. Vmax was elevated from ∼0.28 min−1 to 2.4 ± 0.4 and 0.85 ± 0.02 min−1 when Ric-8BFL or Ric-8BΔ9 proteins were assayed, respectively (Fig. 4E). The Km of Gαq for GTP (alone) could not be estimated reliably because Gαq has such low intrinsic GTPase activity. Ric-8A and Ric-8BFL increased Gαq activity in a substrate-dependent manner to estimated Vmax values of 0.53 ± 0.02 and 0.31 ± 0.01, respectively. The estimated Km values of Gαq for GTP in the presence of Ric-8A and Ric-8BFL were 9.8 ± 0.7 and 3.1 ± 0.3 μm, respectively. Due to technical limitations of the assay (high Pi product background with increasing substrate concentration), the Km values of GTP for Gαs short in the presence of Ric-8BFL (∼42 μm) and GTP for Gαq in the presence of Ric-8A (∼9.8 μm) can only be considered estimates because measurements could not be made using GTP concentrations above the estimated Km values. Nonetheless, Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A dramatically increased the apparent Km values of Gαs short and Gαq for GTP, respectively. These elevated Km values provide a partial explanation for the observation that GTP binding to open Ric-8B·Gαs short complexes was inhibited and for why Ric-8BFL was inhibitory to Gαs short GTP binding at low GTP concentrations. At physiological GTP concentrations (250–700 μm) (41), Ric-8BFL would act as a GEF activator (and not an inhibitor) of Gαs short.

Gβγ is obligatory for GPCR GEF activity but inhibitory to Ric-8A activation of Gαq (7). Because Gβγ was found to bind Ric-8 isoforms weakly (Fig. 1C) (33), it was tested for its capacity to regulate Ric-8B-influenced Gαs short and Gαq steady state GTPase activities at low GTP concentration and with reduced Mg+2 levels (both reagents inhibit Gβγ binding to Gα). Gβγ markedly inhibited intrinsic and all Ric-8 isoform-influenced Gαs short and Gαq steady state GTPase activities (supplemental Fig. S6). Ric-8 and Gβγ regulate Gα activity independent of each other in vitro.

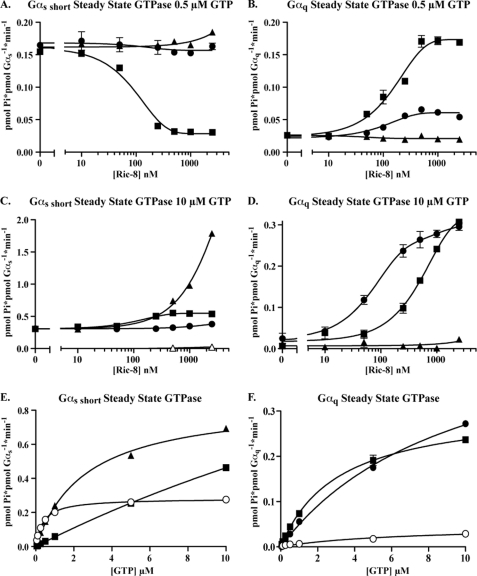

Guanine Nucleotide Content of Ric-8B·Gα Complexes

To clarify findings from the kinetic assays and better define the functional characteristics of Ric-8B interactions with G protein subunits, the guanine nucleotide states of Gαs short and Gαq when bound to Ric-8 proteins were determined using a gel filtration-based assay in which Ric-8A was shown to bind nucleotide-free Gαi1 (7). A molar excess of Gαs short or Gαq (10 μm) was incubated with Ric-8 protein (5 μm) in the presence of 100 μm [35S]GTPγS or GDP. The protein mixtures were resolved over Superdex 75 and 200 size exclusion columns arranged in tandem. The column eluates were fractionated. Proteins and GTPγS present in the fractions were identified by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and UV280 absorbance or scintillation counting. Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 formed stoichiometric complexes with Gαs short in the presence of GDP (Fig. 5, A and B). Given that both Ric-8B isoforms were efficacious Gαs short GDP release factors (Fig. 3), and by analogy to the nucleotide-free Ric-8A·Gαi1 complex, it was concluded that Ric-8B·Gαs short complexes formed in the presence of GDP were nucleotide-free (7, 30). Interestingly, Ric-8BFL, but not Ric-8BΔ9, formed substantial stable complex with Gαs short-GTPγS. Based on a protein complex stoichiometry of 1:1, ∼60.8% of the Ric-8BFL was bound to Gαs short-GTPγS (Fig. 5A). The measured fraction of GTPγS bound to Gαs short in complex with Ric-8BFL did not differ from that bound to monomeric Gαs short (∼38%). The experiments with Gαq confirmed the capacity of Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A, but not Ric-8BΔ9, to stimulate Gαq nucleotide exchange. Ric-8BFL bound Gαq with 1:1 stoichiometry in the presence of GDP but was bound to very little detectable Gαq in the presence of GTPγS (Fig. 5C). The monomeric Gαq pool had a substantial fraction of bound GTPγS (∼27%), showing that Ric-8BFL promoted Gαq GTPγS binding. Ric-8A acted similarly to Ric-8BFL in promoting Gαq GTPγS binding, although a substantial portion of Ric-8A remained bound to Gαq-GTPγS (∼50%) (supplemental Fig. S7). At the high protein concentrations used in these experiments, a nucleotide preference of Ric-8BΔ9 Gαq binding was not observed. Ric-8BΔ9 bound ∼35% of the Gαq, whether GDP or GTPγS was present, but the Ric-8BΔ9·Gαq complex did not contain GTPγS (Fig. 5D). Notably, the monomeric Gαq pool in the Ric-8BΔ9 experiment had very little bound GTPγS, confirming that Ric-8BΔ9 is not a Gαq GEF.

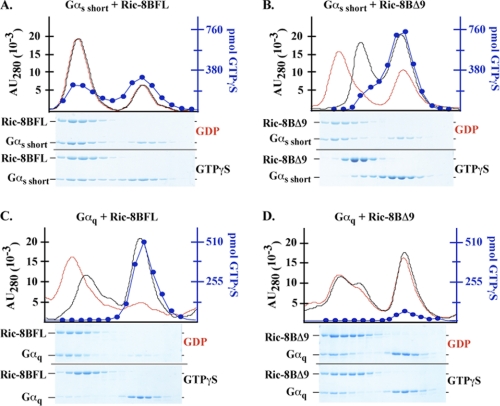

FIGURE 5.

Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 bind differentially to GDP- and GTPγS-bound Gαs short and Gαq. Ric-8B proteins (5 μm) were mixed with Gαs short (A and B) or Gαq (10 μm each) (C and D) in the presence of 100 μm GDP or [35S]GTPγS (SA 35,000 cpm/pmol) and incubated for 15 min at 22 °C. The protein/nucleotide mixtures were centrifuged to remove particulate and gel-filtered over Superdex 75 and Superdex 200 columns arranged in tandem. The column eluates were fractionated, and protein-containing fractions were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE and scintillation counting to quantify the amount of GTPγS contained in each fraction (blue traces, [35S]GTPγS experiments only). UV absorbance traces (AU280) of the column eluates for the GDP (red traces) and GTPγS (black traces) experiments were co-plotted with the GTPγS measurements (blue traces) on double-labeled y axis plots. Left to right, species eluted in decreasing molecular weight from the columns.

Ric-8 Interactions with Gα-GTP

Isolation of stable Ric-8BFL·Gαs short·GTP and Ric-8A·Gαq·GTP complexes may reflect high affinities that Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A have for the respective G protein subtypes. Ric-8 proteins might influence Gα steady state GTPase activity as a consequence of interaction with Gα-GTP by altering the rate of single turnover GTP hydrolytic activity or by promoting GTP release from Gα prior to hydrolysis. The latter possibility would explain the ability of Ric-8BFL to greatly increase the apparent estimated Km for GTP binding to Gαs short (Fig. 4E) and/or to reduce Gαs short GTPγS end point binding stoichiometry (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S4). Measurements of Ric-8 influence on Gαs short single turnover GTP hydrolytic activity were conducted. Gαs short was loaded with [γ-32P]GTP in the absence of Mg2+, gel-filtered to remove excess nucleotide, and incubated in timed, single turnover GTPase reactions containing MgCl2 and/or excess Ric-8 proteins (500 nm) at 4 °C. The rates of Gαs short GTP hydrolysis were nearly equivalent (range of 1.07–1.16 min−1) in each experiment (Fig. 6). All Ric-8 proteins (and notably Ric-8BFL) did not affect Gαs short single turnover GTPase activity.

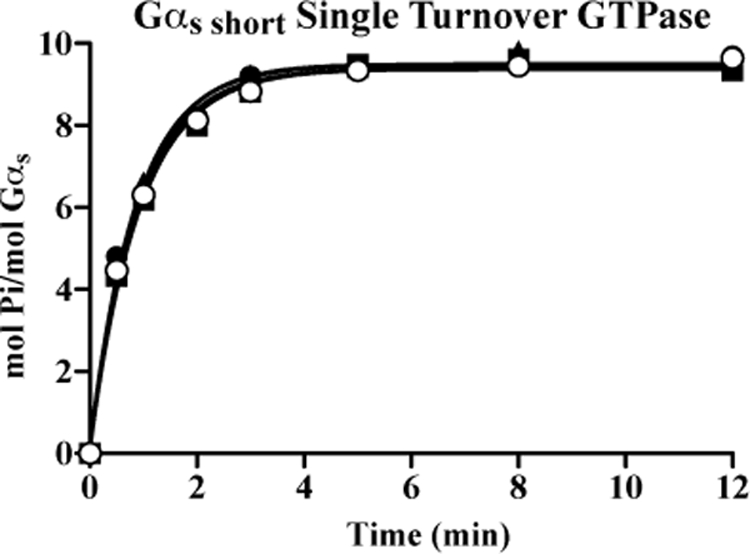

FIGURE 6.

Ric-8 proteins do not affect Gαs short single turnover GTPase activity. Gαs short was loaded with [γ-32P]GTP at 25 °C in buffer lacking Mg+2 and separated from free GTP by rapid gel filtration. Gαs short-[γ-32P]GTP (60 nm, actual concentration) single turnover GTPase reactions were initiated at 4 °C by the addition of buffer containing MgCl2 (○), MgCl2 and Ric-8BFL (■), Ric-8BΔ9 (▴), or Ric-8A (●) (500 nm each). Duplicate reactions were quenched in acidic charcoal suspension at the indicated times and processed as described. Data are representative of three or more independent experiments. The mol of phosphate (Pi) released/mol of Gαs short over time were plotted using GraphPad Prism version 5.0 and one-phase association functions. Note that some points were hidden by other data.

Ric-8-influenced GTPγS release measurements from prepared Gα-[35S]GTPγS substrates were conducted in the face of excess GTPγS or GDP challenge. These measurements allowed determination of Ric-8 promotion of Gα GTP release, GTP for GTP futile nucleotide exchange, and/or GDP for GTP reverse nucleotide exchange. With GTPγS challenge, Ric-8BFL stimulated rapid and complete Gαs short GTPγS release. Gαs short alone or Gαs short in the presence of Ric-8BΔ9 or Ric-8A retained prebound GTPγS (Fig. 7A). With GDP challenge, Ric-8BFL stimulated Gαs short GTPγS release with similar kinetics, but the extent of the release did not go to completion (∼45%) (supplemental Fig. S8). As a consequence, Ric-8BFL catalyzes Gαs short GTP for GTP futile nucleotide exchange but probably does not induce GDP for GTP exchange. Stimulation of Gαq GTPγS release by Ric-8 proteins was far less dramatic than that observed for the Ric-8BFL and Gαs short pair and did not go to completion (Fig. 7B). Only Ric-8A stimulated measurable Gαq GTPγS release. Ric-8BFL did not. This was consistent with the finding that a stable complex of Ric-8A·Gαq·GTPγS (supplemental Fig. S7) but not Ric-8BFL·Gαq·GTPγS (Fig. 5C) could be isolated and reflects the higher affinity that Ric-8A probably has over Ric-8BFL for Gαq.

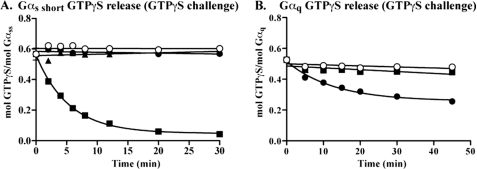

FIGURE 7.

Ric-8 proteins catalyze GTPγS/GTPγS futile nucleotide exchange. Gαs short (A) and Gαq (B) were loaded to completion with [35S]GTPγS as described. GTPγS release from Gα (100 nm) was measured over the indicated time courses at 25 °C (Gαs short) or 30 °C (Gαq) after the addition of 100 μm non-radioactive GTPγS (○) and/or Ric-8BFL (■), Ric-8A (●), and/or Ric-8BΔ9 (▴) (for Gαs short only) (500 nm each) using the GTPγS binding assay nitrocellulose filter binding method. The data were fit to one-phase exponential dissociation functions (Ric-8BFL/Gαs short and Ric-8A/Gαq) or otherwise plotted by linear regression using GraphPad Prism. Results are the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. Note that most error bars are smaller than the actual plotted symbols, and some points were hidden by other data.

DISCUSSION

We report that Ric-8BFL binds natively expressed Gαs and, to lesser degrees, Gαq and Gα13. Ric-8BFL is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for these G proteins and Gαolf. GTP concentration was an essential parameter that influenced Ric-8B exchange-stimulatory activity for Gαs. At higher GTP substrate concentrations (≥10 μm), both Ric-8B isoforms were efficacious Gαs GEF activators of steady state GTPase activity and GTPγS binding. At lower GTP levels (≤1 μm), Ric-8BΔ9 marginally activated Gαs steady state GTPase activity, and Ric-8BFL was a potent inhibitor. These observations were reconciled by the idea that Ric-8 proteins interact with highest affinity with the nucleotide-free form of the Gα subunits that each bind. As a consequence, Ric-8 proteins dramatically raised the apparent Km values of GTP binding to Gα. After rapid Ric-8B stimulation of GDP release from Gαs, cellular levels of GTP (∼500 ± 200 μm) would displace Ric-8B from the nucleotide-free Ric-8B·Gασ complex and drive the exchange reaction to completion in the forward direction to produce dissociated Ric-8B and activated Gαs-GTP (Fig. 8). Ric-8BFL and Ric-8A also activated Gαq with GTP dependence, but both were activators at all concentrations of GTP tested.

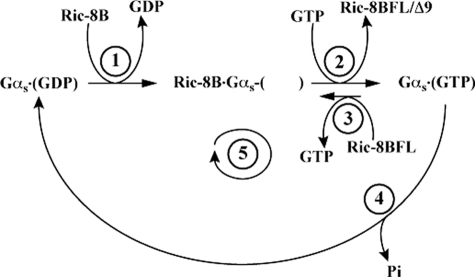

FIGURE 8.

Ric-8B regulation of Gαs catalysis. Ric-8B is a Gαs GRF with GTP-dependent GEF activity. At low GTP (<10 μm), Ric-8B-stimulated Gαs short GDP release (step 1) was significantly faster than observed Ric-8B-stimulated GTP(γS) binding (step 1 plus step 2), whereas intrinsic Gαs short GDP release and observed GTPγS binding rates were equivalent. Ric-8B-FL potently inhibited Gαs short steady state GTPase activity (step 5) at low GTP, due to its capacity to dramatically increase the Km of GTP for Gαs short (∼385 nm to an estimated value of ∼42 μm) and to stimulate futile GTP for GTP exchange (step 3). Ric-8BΔ9 did not increase the Km of GTP for Gαs short nearly as much (∼2.6 μm) and did not stimulate futile GTP/GTP exchange. These results probably reflect a higher affinity that Ric-8BFL has over Ric-8BΔ9 for Gαs. Neither Ric-8B isoform had any effect on Gαs single turnover GTPase activity (step 4). At higher GTP (>10 μm), Ric-8BFL and Ric-8BΔ9 stimulated Gαs short nucleotide exchange and steady state GTPase activities. At physiological GTP, Ric-8B-catalyzed exchange is predicted to proceed in the forward direction to produce activated Gαs-(GTP).

Comparison of the results from the quantitative Ric-8·G protein binding studies (Fig. 1) with the guanine nucleotide kinetic assays (Figs. 2–7) allowed prediction of the relevant cellular interactions between the individual Ric-8 proteins (A, BFL, and BΔ9) and G protein subtypes of all four classes. With little exception, the amount of G protein recovered from cells or membrane extracts using particular Ric-8 baits correlated with the ability and degree to which that Ric-8 protein stimulated Gα subunit nucleotide exchange. The relevant Gα interactions with Ric-8A probably include the Gαi, Gαq, and Gα12/13 classes. Ric-8A recovered the highest percentages of these G proteins in the pull-down experiments and activated the GTPγS binding rates of each infinitely faster (Gαi1), 5 times faster (Gαq), or 2.3 times faster (Gα13) than an equivalent concentration of Ric-8BFL. Ric-8A also increased the apparent Km of Gαq for GTP more so than Ric-8BFL.

Relevant Ric-8BFL cellular interactions certainly include and may be restricted to the Gαs class, although low amounts (<1.6% of input) of Gαq and Gα13 were recovered in Ric-8BFL pull-down experiments (Fig. 1A). Ric-8BΔ9 appeared to have a quite low albeit exclusive affinity for Gαs-class subunits. The dramatic enhancement of the estimated Km of GTP for Gαs short in the presence of Ric-8BFL (∼110 times higher than Gαs alone) further supported the idea that Gαs short is the relevant Ric-8BFL-interacting Gα subunit in cells. Ric-8BΔ9 enhanced the apparent Km of GTP for Gαs short to a lesser degree (∼6.7 times higher than Gαs alone). This was consistent with the fact that little Gαs was isolated by Ric-8BΔ9 in membrane extract pull-down experiments despite Ric-8BΔ9 activating Gαs short GDP release and GTPγS binding activities efficaciously. The measured concentration of Gαs short in the extract pull-down input material was ∼5–10 nm (Fig. 1A). Gαs short concentrations used in the GEF assays (Figs. 2 and 3) and purified component pull-down experiments (Fig. 1C) were 100 nm and 1 μm, respectively. If the Kd of Gαs·Ric-8BΔ9 binding lies between 10 and 100 nm, this could explain the apparent discrepancy in these results. Because Ric-8BΔ9 only activated Gαs short and did not activate Gαolf or any other tested class of Gα subunit, structural features of the 40-amino acid region within Ric-8BFL that are absent in the Ric-8BΔ9 isoform (by alternative splicing of the entirety of exon 9) may allow Ric-8BFL to bind Gα subunits with higher affinity and/or to possess a better ability to act as a GEF.

The biochemical data here show that Ric-8B should act as a directional Gαs GEF at physiological GTP levels. This seemingly corroborates propositions that overexpressed Ric-8B potentiated Gs/Golf signaling in cells by acting as a G protein activator (GEF) (13, 16, 17, 33). Although plausible, we must consider an alternate interpretation to this model, given that many independent studies have shown that Ric-8 proteins regulate G protein steady state and plasma membrane expression (18–23). Ric-8B might not facilitate Gs/Golf signaling as a direct G protein activator but may do so as a facilitator or enhancer of Gαs short/Gαolf protein expression. In this capacity, Ric-8 might promote G protein biosynthesis and/or prevent G protein turnover by acting analogously toward Gα subunits as PhLP1 (phosducin-like protein 1) acts upon Gβ and Drip78 (dopamine receptor-interacting protein 78) acts on Gγ prior to Gβγ dimer formation (42–47). In this putative role, perturbation of Ric-8 expression would result in Gα protein chains that do not fold efficiently and/or be passed off from Ric-8 to Gβγ for initial G protein trimer assembly on intracellular membranes.

Another possible means of action of predominantly cytosolic Ric-8 proteins is as an escort-like component for G proteins that shuttle among membranes. The time required for Gαq to transit in retrograde fashion from the plasma membrane to the Golgi during a proposed palmitoylation/depalmitoylation cycling process occurred much faster than expected if the trafficking was a vesicle-mediated transport event (48–50). This implied that Gα transits rapidly through the cytosol to reach the outer face of the Golgi. One could easily envision that an escort protein, such as Ric-8 or Gβγ, is required to aid Gα during this transit lest it signal inappropriately. In conditions of reduced Ric-8 expression, Gα subunits not escorted to the proper cellular compartment(s) might be expected to be more sensitive to turnover.

How can these models of Ric-8 control of G protein expression be reconciled with our biochemical results that clearly show that Ric-8B and Ric-8A are GEFs? We envision a model in which so-called GEF activity may not necessarily or always be a means to control G protein activation status to directly evoke a signaling output. Rather, GEF activity could be a means to simply dissociate Ric-8 from Gα. With the exception of a few specific low affinity interactions of Ric-8 isoforms and Gα-GTP (Figs. 5 and 7 and supplemental Fig. S7), Ric-8 proteins dissociate from Gα when Gα adopts the GTP-bound conformation. It stands to reason that whatever Ric-8 proteins do to promote or preserve Gα expression, they must bind Gα at one point and become dissociated at another. Use of the G protein GDP/GTP conformational switch could be the mechanism by which Ric-8 is dissociated from Gα at the proper temporal/spatial location. The question of what activates or regulates Ric-8 GEF activity in this regard also becomes pertinent. If Ric-8 is an escort factor for Gα during folding or a particular trafficking step, then a third component in addition to GTP may be necessary when the Ric-8·Gα complex reaches its destination to “activate” exchange and dissociate Ric-8 and Gα. This would release Gα to perform non-Ric-8 functions.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM088242 (to G. G. T.). This work was also supported by New York State Stem Cell Science (NYSTEM) Grant C024307 (to G. G. T.) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant T32 DA07232 (to P. C.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S8.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- Gαs short

- G protein αs short isoform

- Gαs long

- G protein αs long isoform

- GRF

- GDP release factor

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GTPγS

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- SA

- specific activity

- TAP

- tandem affinity purification

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- C12E10

- deionized polyoxyethylene 10 lauryl ether

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- m/v

- mass/volume.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gilman A. G. (1987) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56, 615–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blumer J. B., Chandler L. J., Lanier S. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15897–15903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cismowski M. J. (2006) Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 17, 334–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia-Marcos M., Ghosh P., Farquhar M. G. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3178–3183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Natochin M., Campbell T. N., Barren B., Miller L. C., Hameed S., Artemyev N. O., Braun J. E. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30236–30241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sato M., Blumer J. B., Simon V., Lanier S. M. (2006) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 46, 151–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tall G. G., Krumins A. M., Gilman A. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8356–8362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miller K. G., Emerson M. D., McManus J. R., Rand J. B. (2000) Neuron 27, 289–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reynolds N. K., Schade M. A., Miller K. G. (2005) Genetics 169, 651–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schade M. A., Reynolds N. K., Dollins C. M., Miller K. G. (2005) Genetics 169, 631–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Klattenhoff C., Montecino M., Soto X., Guzmán L., Romo X., García M. A., Mellstrom B., Naranjo J. R., Hinrichs M. V., Olate J. (2003) J. Cell. Physiol. 195, 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tall G. G., Gilman A. G. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102, 16584–16589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Von Dannecker L. E., Mercadante A. F., Malnic B. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 3793–3800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoshikawa K., Touhara K. (2009) Chem. Senses 34, 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malnic B., Gonzalez-Kristeller D. C. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1170, 150–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Von Dannecker L. E., Mercadante A. F., Malnic B. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 9310–9314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhuang H., Matsunami H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15284–15293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Afshar K., Willard F. S., Colombo K., Siderovski D. P., Gönczy P. (2005) Development 132, 4449–4459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. David N. B., Martin C. A., Segalen M., Rosenfeld F., Schweisguth F., Bellaïche Y. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1083–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hampoelz B., Hoeller O., Bowman S. K., Dunican D., Knoblich J. A. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1099–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang H., Ng K. H., Qian H., Siderovski D. P., Chia W., Yu F. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1091–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nagai Y., Nishimura A., Tago K., Mizuno N., Itoh H. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11114–11120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chan P., Gabay M., Wright F. A., Kan W., Oner S. S., Lanier S. M., Smrcka A. V., Blumer J. B., Tall G. G. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2625–2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Linder M. E., Middleton P., Hepler J. R., Taussig R., Gilman A. G., Mumby S. M. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 3675–3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pang I. H., Sternweis P. C. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 18707–18712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mumby S. M., Gilman A. G. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 195, 215–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kozasa T. (1999) in G Proteins: Techniques of Analysis (Manning D. R. ed) pp. 23–38, CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kozasa T., Gilman A. G. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1734–1741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee E., Linder M. E., Gilman A. G. (1994) Methods Enzymol. 237, 146–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tall G. G., Gilman A. G. (2004) Methods Enzymol. 390, 377–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sternweis P. C., Robishaw J. D. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 13806–13813 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ross E. M. (2002) Methods Enzymol. 344, 601–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kerr D. S., Von Dannecker L. E., Davalos M., Michaloski J. S., Malnic B. (2008) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 38, 341–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Itoh H., Gilman A. G. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 16226–16231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hepler J. R., Kozasa T., Smrcka A. V., Simon M. I., Rhee S. G., Sternweis P. C., Gilman A. G. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 14367–14375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Singer W. D., Miller R. T., Sternweis P. C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19796–19802 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ross E. M., Wilkie T. M. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69, 795–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ross E. M. (2008) Curr. Biol. 18, R777–R783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brandt D. R., Ross E. M. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 266–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jameson E. E., Roof R. A., Whorton M. R., Mosberg H. I., Sunahara R. K., Neubig R. R., Kennedy R. T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7712–7719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Traut T. W. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 140, 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lukov G. L., Baker C. M., Ludtke P. J., Hu T., Carter M. D., Hackett R. A., Thulin C. D., Willardson B. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 22261–22274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lukov G. L., Hu T., McLaughlin J. N., Hamm H. E., Willardson B. M. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1965–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McLaughlin J. N., Thulin C. D., Hart S. J., Resing K. A., Ahn N. G., Willardson B. M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7962–7967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wells C. A., Dingus J., Hildebrandt J. D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20221–20232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Willardson B. M., Howlett A. C. (2007) Cell. Signal. 19, 2417–2427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dupré D. J., Robitaille M., Richer M., Ethier N., Mamarbachi A. M., Hébert T. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13703–13715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chisari M., Saini D. K., Kalyanaraman V., Gautam N. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24092–24098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saini D. K., Chisari M., Gautam N. (2009) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30, 278–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tsutsumi R., Fukata Y., Noritake J., Iwanaga T., Perez F., Fukata M. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 435–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.