Abstract

Variations in the light environment require higher plants to regulate the light harvesting process. Under high light a mechanism known as non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) is triggered to dissipate excess absorbed light energy within the photosystem II (PSII) antenna as heat, preventing photodamage to the reaction center. The major component of NPQ, known as qE, is rapidly reversible in the dark and dependent upon the transmembrane proton gradient (ΔpH), formed as a result of photosynthetic electron transport. Using diaminodurene and phenazine metasulfate, mediators of cyclic electron flow around photosystem I, to enhance ΔpH, it is demonstrated that rapidly reversible qE-type quenching can be observed in intact chloroplasts from Arabidopsis plants lacking the PsbS protein, previously believed to be indispensible for the process. The qE in chloroplasts lacking PsbS significantly quenched the level of fluorescence when all PSII reaction centers were in the open state (Fo state), protected PSII reaction centers from photoinhibition, was modulated by zeaxanthin and was accompanied by the qE-typical absorption spectral changes, known as ΔA535. Titrations of the ΔpH dependence of qE in the absence of PsbS reveal that this protein affects the cooperativity and sensitivity of the photoprotective process to protons. The roles of PsbS and zeaxanthin are discussed in light of their involvement in the control of the proton-antenna association constant, pK, via regulation of the interconnected phenomena of PSII antenna reorganization/aggregation and hydrophobicity.

Keywords: Allosteric Regulation, Membrane Biophysics, Photosynthesis, Plant, Proton Transport, PsbS, Light Harvesting Complex, Nonphotochemical Quenching, pK

Introduction

Sunlight can fluctuate frequently and dramatically in both intensity and spectral quality during the day. The photosynthetic membrane of higher plants has evolved to operate efficiently under such light conditions. In shade, large arrays of antenna complexes efficiently harvest and deliver photon energy to the photochemical reaction centers for use in photosynthesis. In high light the membrane switches to a photoprotective state where the excess absorbed energy, which has the potential to cause damage, is safely dissipated as heat (1, 2). The amount of energy dissipation can be monitored by the non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence (NPQ)2 (1, 2). The major component of NPQ, qE, is rapidly reversible in the dark and is dependent upon the level of the transmembrane proton gradient (ΔpH). ΔpH acts as a feedback signal indicating the degree of saturation of photosynthetic electron transport (1, 2). ΔpH can be generated by linear electron flow (LEF), which involves the oxidation of water by photosystem II (PSII) and the transfer of electrons to NADP+ via the cytochrome b6f and photosystem I (PSI) complexes (3). In addition, cyclic electron flow (CEF), which involves the transfer of electrons in a closed loop around cytochrome b6f and PSI was reported to contribute to ΔpH (4–6). The contribution of CEF to ΔpH generation is essential for maintaining the correct ATP/NADPH ratio for CO2 fixation in the chloroplast stroma (6). Imbalance in the ATP/NADPH ratio can limit the acceptor side of PSI in high light impairing LEF and thus generation of ΔpH and qE (7).

The ΔpH is known to act upon several targets to regulate light harvesting. It protonates the light harvesting complexes of PSII (LHCs) (8, 9), the LHC-related PsbS protein (10), and also activates the violaxanthin de-epoxidase enzyme that converts the LHC-bound xanthophyll cycle carotenoid from violaxanthin to zeaxanthin (11). Interaction of these three factors is believed to bring about formation of a quencher of chlorophyll singlet excited states (1, 2). The relationship between qE and ΔpH varies depending upon the de-epoxidation state of the xanthophyll cycle carotenoids (12–20). In the absence of zeaxanthin this relationship is sigmoidal with a pK reported in the range of 4.7–5.0, whereas in the presence of zeaxanthin it is hyperbolic with a pK reported in the range of 5.7–6.5 (12–20). Thus, because the physiologically typical values of lumen pH encountered in excess light are estimated in the pH 5.5–5.8 range (21), qE is much smaller in the absence of zeaxanthin (22, 23). By affecting the sensitivity of qE to ΔpH, zeaxanthin also modulates the kinetics of qE, enhancing the rate of formation and retarding the rate of qE relaxation (18, 24).

The exact site of qE within the PSII antenna and the pigments involved in the quenching mechanism remain under debate. Earlier, it was proposed that PsbS itself is the site of quenching (10). In Arabidopsis mutants lacking PsbS (npq4) qE was completely abolished and only a slowly forming and relaxing NPQ was present (25). The characteristic 535 nm absorption change (ΔA535), which is believed to monitor a structural change within the PSII antenna that accompanies qE, was also reported to be absent (25). The npq4 plants showed enhanced sensitivity to photoinhibition of PSII in excess light and impaired Darwinian fitness in fluctuating light environments (26, 27). Conversely, if PsbS was overexpressed then the level of qE was doubled compared with the wild-type (26). When zeaxanthin was mixed with purified PsbS its absorption spectrum was red-shifted mimicking the ΔA535 change (28). PsbS was therefore suggested to act as both the sensor of ΔpH and the binding site of a putative zeaxanthin quencher (10). However, recently new evidence has emerged that argues against a PsbS-zeaxanthin complex being the site of qE. First, both reconstituted and native PsbS were found consistently unable to specifically bind pigments (29). Second, PsbS was still able to perform its function in the absence of zeaxanthin (30, 31). Finally, npq4 plants were still shown to possess wild-type levels of photoprotective energy dissipation albeit forming and relaxing 10 times more slowly than in the wild-type (32). The slowly forming NPQ in the npq4 mutant was dependent upon ΔpH and was also characterized by the ΔA535 absorption change, suggesting this signal does not arise from a PsbS-zeaxanthin complex (32). Purified LHCs, on the other hand, readily adopt quenching states upon aggregation in low detergent buffers indicating that they already contain quenching sites (1, 13, 17). This in vitro quenching in LHCs was found to be modulated by pH and xanthophyll cycle carotenoids and possesses many of the spectroscopic fingerprints associated with qE (1, 13, 17). It has thus been suggested that PsbS plays an indirect role in qE, somehow supporting the formation of quenching within one, several, or all of the LHCs (17, 33, 34).

The idea of an indirect role of PsbS in qE is corroborated by its influence on the organization of PSII and LHCs within the thylakoid grana membrane. PSII core dimers are organized within large supercomplexes containing two copies each of the minor LHCs: CP24, CP26, and CP29, and four trimeric LHCII complexes (35). These PSII-LHCII supercomplexes can further associate to form large semi-crystalline domains within the grana (35). PsbS levels were found to influence the amount of these semi-crystalline PSII-LHCII domains and to affect the Mg2+ dependence of grana membrane organization (36, 37). Disrupted macro-organization of PSII-LHCII supercomplexes in the grana membranes of Arabidopsis mutants lacking certain LHC proteins has been shown to affect the ΔpH sensitivity of qE (19). One possibility therefore is that the modified grana membrane organization in the absence of PsbS shifts the ΔpH threshold for activation of qE to higher values.

To investigate this possibility further we examined ways to increase the levels of ΔpH in chloroplasts. Artificial mediators of CEF around PSI such as diaminodurene (DAD) and phenazine metasulfate (PMS) were reported to generate high levels of ΔpH chloroplasts, even in the presence of the LEF inhibitor 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) (38, 39). The ability of DAD and PMS to form ΔpH and thus induce quenching in the presence of DCMU provided the first evidence for a photoprotective form of quenching that was independent of the PSII redox state (38). Later, it was shown that DAD could enhance qE and ΔpH in pea chloroplasts (40). DAD, in either its neutral or protonated forms, in the absence of ΔpH was insufficient for observation of quenching, indicating that the compound is not itself a quencher (41, 42). The ability of DAD and PMS to modulate CEF relies upon their reduction by the PSI acceptor side. This leads to proton uptake by the mediators from the stroma, diffusion through the membrane, oxidation by the PSI donor side, and proton release into the lumen (42). This artificial cycle around PSI was found to be dibromothymoquinone insensitive and is thus most likely independent of cytochrome b6f involvement (43). In the following study it is shown that by enhancing the level of ΔpH by using DAD and PMS that qE can be observed in intact Arabidopsis chloroplasts from plants lacking the PsbS protein. Moreover, qE in the absence of PsbS is associated with Fo quenching, protects PSII from photoinhibition, is modulated by zeaxanthin, and is accompanied by the ΔA535 absorption change.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chloroplast Isolation

Arabidopsis thaliana cv Columbia and npq4 mutant derived from it were grown as previously described (44). Intact chloroplasts were prepared as previously described (30). Chloroplasts devoid of zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin (v) were prepared from spinach leaves dark adapted for 1 h. Chloroplasts enriched in zeaxanthin (z) were prepared from leaves pre-treated for 30 min at 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 under 98% N2, 2% O2.

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Induction

Chlorophyll fluorescence was measured with a Dual-PAM-100 chlorophyll fluorescence photosynthesis analyzer (Walz, Germany) using the liquid cell adapter. 1.4 ml of intact chloroplasts were measured in a quartz cuvette at a concentration of 35 μm chlorophyll under continuous stirring. The reaction medium contained 0.45 m sorbitol, 20 mm HEPES, 20 mm MES, 20 mm sodium citrate, pH 8.0, 10 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaHCO3, 0.1% BSA, 5 mm MgCl2. Ascorbate was omitted from all buffers to prevent further de-epoxidation taking place during illumination. Control chloroplasts showed a high degree of intactness and qE without addition of exogenous electron acceptors. Where mentioned 400 μm DAD or 100 μm PMS (in their reduced state) was added to intact chloroplasts to stimulate CEF around PSI in the DAD or PMS-treated chloroplasts. Where mentioned DAD-treated chloroplasts were supplemented with either 50 μm DCMU (to inhibit PSII reduction of plastoquinone and thus LEF) or 2 μm nigericin (to uncouple the thylakoid membrane). Actinic illumination was provided by arrays of 635 nm LEDs. Fo and Fo′ (the fluorescence level with PSII reaction centers open) was measured in the presence of 10 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 measuring beam. Fs is the steady state fluorescence level under actinic illumination. The maximum fluorescence in the dark-adapted state (Fm), during the course of actinic illumination (Fm′), and in the subsequent dark relaxation periods (Fm") was determined using a 0.8-s saturating light pulse (4000 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Fluorescence parameters were calculated as follows: qP = (Fm′ − Fs)/(Fm′ − Fo′) and NPQ = (Fm − Fm′)/Fm′).

Measurement of ΔpH

ΔpH was determined from the measurement of 9-aminoacridine (9-AA) fluorescence using the Dual-ENADPH and Dual-DNADPH modules for the Dual-PAM-100 chlorophyll fluorescence photosynthesis analyzer (Walz, Germany). Intact chloroplasts were treated as described above in the presence of 1 μm 9-AA. Excitation was provided by 365 nm LEDs and fluorescence emission was detected between 420 and 580 nm. Lumen pH and ΔpH were estimated from the values of 9-AA quenching, using the equation: ΔpH = log[1/(1 − Q) + Q/(1 − Q)](Vout/Vin), where Q is the level of 9-AA quenching, Vout is the sample volume (1.4 ml), and Vin is the lumen volume (56 μl/mg of chlorophyll) calculated for the sample chlorophyll concentration of 35 μg of chlorophyll/ml using the relationship Vin = 50 liters/mol assuming the internal volume of thylakoids is 56 μl/mg of chlorophyll (45).

ΔpH versus qE Titrations

Titrations of the ΔpH dependence of qE were carried out by varying the light intensity of 635 (for actinic illumination) or 710 nm (for far-red illumination) LEDs from 0 to 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 to produce different amplitudes of ΔpH and the amount of qE that was formed following 5 min of illumination at each light intensity was recorded. For titrations, the amount of qE was expressed on the linear quenching scale where qE = (Fm" − Fm′)/Fm". The titration data were fitted to a curve defined by the equation qE = qEmaxΔpHn/(ΔpHn + ΔpH0n), where qEmax is the theoretical maximum qE, ΔpH is the level of ΔpH at a particular light intensity, ΔpH0 is the level of ΔpH at which qE = 0.5 qEmax, and n is the sigmoidicity parameter (Hill coefficient)(18). pK was then estimated by converting ΔpH0 to estimated lumen pH by subtracting ΔpH0 from the starting pH (8.0).

pH Versus qE Titrations

As an alternative to estimates of lumen pH based on 9-AA quenching acid titrations were also performed. qE in DAD-treated chloroplasts was formed during 5 min illumination with 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 635 nm LED light. After 5 min an aliquot of concentrated HCl was added to the solution to change the bulk pH to a given value between 3.0 and 8.0 and the light was then immediately turned off. The amount of quenching at pH 8.0 was subtracted from the amount of quenching preserved at each pH value to give the level of qE. The titration data were fitted to a curve defined by the equation qE = qEmaxpHn/(pHn + pH0n), where qEmax is the theoretical maximum qE, pH is the pH of the bulk medium, pH0 (pK) is the level of pH at which qE = 0.5 qEmax, and n is the sigmoidicity parameter (Hill coefficient) (18).

ΔA535 Absorption Changes

Absorption changes in the 410–565 nm region were measured as previously described (44).

Pigment Analysis

Pigment composition was determined as previously described (46). Chlorophyll concentration was determined according to the method of Porra et al. (47).

RESULTS

The maximum level of ΔpH, measured by 9-AA quenching, in control npq4 chloroplasts prepared from light-treated leaves (npq4(z)) (Table 1) was 37 ± 2.4%. This level of 9-AA quenching corresponds to a ΔpH of 2.4 and an estimated lumen pH of 5.6, which is broadly consistent with estimates of the normal physiological maximum (21, 48). The addition of DAD to npq4(z) chloroplasts enhanced the level of 9-AA quenching to 58.0 ± 3.4% (Fig. 1A), corresponding to a ΔpH of 4.1 and an estimated lumen pH of 3.9. A similar increase in 9-AA quenching compared with the control was also observed in DAD-treated wild-type chloroplasts prepared from light-treated leaves (WT(z)) (Table 1) (Fig. 1A). DAD enhanced the level of NPQ in control WT(z) chloroplasts by a factor of 2 (Fig. 1, A and B). In contrast, in control npq4(z) chloroplasts virtually no NPQ was observed within 5 min of illumination. Yet remarkably, in the presence of DAD NPQ was enhanced to almost the same level as in DAD-treated WT(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 1, A and B). More than 90% of the enhanced NPQ in both the DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts was rapidly reversible upon collapse of the ΔpH when the light was turned off (Fig. 1, A and B), suggesting it was of the qE-type. In addition, the quenching of the Fo fluorescence level increased from 0 and 18.0 ± 3.0% in the control npq4(z) and WT(z) chloroplasts, respectively, to 28 ± 2.3 and 30.0 ± 2.0% in those treated with DAD, suggesting the additional quenching occurred within the PSII antenna.

TABLE 1.

Pigment composition for intact Arabidopsis chloroplasts

Chloroplasts devoid of zeaxanthin and antheraxanthin (v) were prepared from Arabidopsis leaves dark-adapted for 1 h. Chloroplasts enriched in zeaxanthin (z) were prepared from Arabidopsis leaves light-treated for 15 min at 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 under 98% N2, 2% O2. Data are expressed as millimoles of carotenoids per mole of Chl a + b molecules and are mean ± S.E. from four replicates. Neo, Lut, XC, DEPs, and Chl a/b: correspond to neoxanthin, lutein, xanthophyll cycle carotenoids (violaxanthin, antheraxanthin, zeaxanthin), xanthophyll cycle de-epoxidation state [(Z + 0.5A)/(V + A + Z)]%, chlorophyll a/b ratio.

| Sample | Neo | Lut | XC | DEPs | Chlorophyll a/b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| npq4(v) | 46 ± 2.2 | 121 ± 3 | 36 ± 3.2 | 0 ± 0 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| npq4(z) | 47 ± 2.2 | 122 ± 2 | 34 ± 2.8 | 33 ± 3.2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| WT(z) | 48 ± 2.3 | 123 ± 3 | 34 ± 1.5 | 34 ± 2.4 | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| WT(v) | 47 ± 3.7 | 119 ± 4 | 31 ± 1.5 | 0 ± 0 | 3.3 ± 0.2 |

FIGURE 1.

A, comparison of 9-AA fluorescence quenching and chlorophyll fluorescence quenching in control and DAD-treated intact Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Chlorophyll fluorescence quenching and 9-AA fluorescence quenching (9-aa) during a 5-min light/5-min dark cycle in control and DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts. Light intensity was 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. B, NPQ during a 5-min light/5-min dark cycle in control WT(z) (white triangles), control npq4(z) (black triangles), DAD-treated WT(z) (white squares), and DAD-treated npq4(z) (black squares) chloroplasts. Light intensity was 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, data are average of three independent experiments ± S.E.

The absence of qE in npq4 plants makes them potentially more vulnerable to rapid exposure to high light. This is due to photoinhibition, the permanent closure of PSII reaction centers as a result of photodamage caused by excess light energy in the absence of NPQ (26, 32). The enhanced NPQ mediated by DAD in npq4(z) and WT(z) chloroplasts was capable of substantially lowering the PSII excitation pressure during illumination as indicated by photochemical quenching (qP) (Fig. 2). Levels of qP in DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts were nearly double those of the control npq4(z) sample during illumination. Upon dark recovery the level of qP in the control npq4(z) chloroplasts was reduced relative to the pre-illumination level, consistent with photoinhibition (32), a feature not observed in control WT(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 2). In contrast, in the DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts the level of qP following dark recovery was virtually identical to the pre-illumination level indicating that the observed NPQ was photoprotective (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Photochemical quenching (qP) during a 5-min light/5-min dark cycle in control WT(z) (white triangles), control npq4(z) (black triangles), DAD-treated WT(z) (white squares), and DAD-treated npq4(z) (black squares) chloroplasts. Light intensity was 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, data are average of three independent experiments ± S.E.

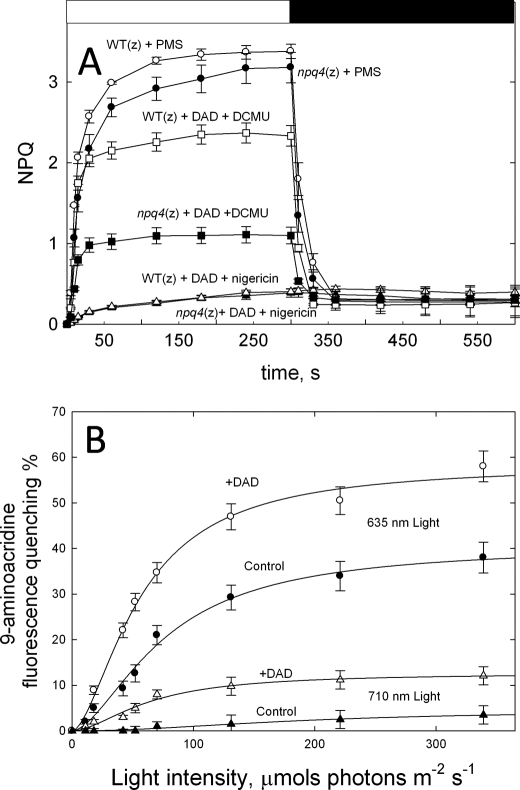

We performed several control experiments to check that the enhanced NPQ in DAD-treated chloroplasts was (a) related to the enhanced ΔpH and (b) that the enhanced ΔpH was due to enhanced CEF around PSI. First we tested whether DAD-treated chloroplasts showed any NPQ in the presence of the uncoupler nigericin. Both npq4(z) and WT(z) chloroplasts showed virtually no NPQ in the presence of nigericin indicating that the quenching relied on the ΔpH (Fig. 3A). Second we tested the effect of inhibiting LEF with DCMU on the enhanced NPQ in DAD-treated chloroplasts. In the absence of LEF, the level of 9-AA quenching was reduced to 55.0 ± 2.6% in WT(z) chloroplasts and 53.0 ± 3.4% in npq4(z) chloroplasts. The level of NPQ was also reduced in both the DCMU/DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 3A) compared with those treated with DAD alone. The decrease in NPQ was larger in npq4(z) than WT(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 3A). However, higher levels of NPQ could still be sustained by ΔpH generated by CEF alone compared with the control (cf. Figs. 1B and 3A). Third, we tested whether PMS, another artificial CEF modulator could induce high ΔpH and NPQ. Addition of PMS to WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts mimicked the effect of DAD on ΔpH increasing 9-AA quenching to 59.0 ± 3.3 and 56.0 ± 2.9%, respectively. The enhanced ΔpH in the presence of PMS supported high levels of NPQ in both WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 3A). Finally, we tested whether far-red light (which is mainly absorbed by PSI) could generate ΔpH in the presence of DAD. Nearly 3 times higher levels of 9-AA quenching were observed in DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts than in the untreated control (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that the ability of DAD to promote NPQ in npq4(z) chloroplasts is indeed associated with the enhanced levels of ΔpH stimulated by enhanced CEF.

FIGURE 3.

A, NPQ during a 5-min light/5-min dark cycle in PMS-treated WT(z) (white circles), PMS-treated npq4(z) (black circles), DAD/DCMU-treated WT(z) (white squares), DAD/DCMU-treated npq4(z) (black squares), DAD/nigericin-treated WT(z) (white triangles) and DAD/nigericin-treated npq4(z) (white triangles) chloroplasts. Light intensity was 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, data are average of three independent experiments ± S.E. B, effect of actinic (635 nm) and far-red (710 nm) illumination intensity on the level of 9-AA fluorescence quenching in npq4(z) chloroplasts in the presence and absence of DAD. Data are average of three independent experiments ± S.E.

To further investigate whether the DAD-mediated NPQ observed in npq4(z) chloroplasts occurred by the same mechanism as qE the kinetics of the ΔA535 absorption change were recorded and compared with the WT(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 4A). In the control WT(z) chloroplasts the ΔA535 signal increases rapidly upon illumination and reaches saturation within ∼1 min. ΔA535 then rapidly relaxes when the light is switched off (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the absence of qE in control npq4(z) chloroplasts no light-induced ΔA535 signal was observed (Fig. 4A). The enhancement of NPQ in DAD-treated WT(z) chloroplasts was accompanied by enhanced levels of ΔA535 (Fig. 3A). DAD treatment also stimulated the rapid emergence of ΔA535 in the npq4(z) chloroplasts with a similar amplitude as in the DAD-treated WT(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 4A). The light-minus-recovery difference spectra in the Soret region for DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts possessed all of the qE characteristic bands that were present in the control WT(z) chloroplasts, with a maximum at 535 nm and minima at 438, 468, and 495 nm (Fig. 4, B and C) (32, 44). These data suggest that the enhanced NPQ in the DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts occurs by the same mechanism as qE.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of DAD on the qE-related absorption changes in the Soret region. A, kinetics of 535 nm absorption change induced during a 5-min light/5-min dark cycle in control and DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts, the reference wavelength used was 565 nm. Light-minus-dark recovery absorption difference spectra in control and DAD-treated (B) WT(z) chloroplasts (C) npq4(z) chloroplasts. Light intensity was 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1.

The differences between WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts were investigated further by determining the qE versus ΔpH titration curves in control and DAD-treated samples (Fig. 5). Because DAD enhances ΔpH it should be possible to extend the known ΔpH versus qE titration curves (12–20). In addition, it can be more carefully ascertained whether DAD generates qE in npq4(z) chloroplasts by merely enhancing ΔpH or rather by modifying the nature of the relationship between qE and ΔpH. The qE data in the presented titrations is expressed according to the linear quenching calculation as qE = (Fm" − Fm′)/Fm", consistent with a number of previous studies (12–20). Both the control and DAD-treated WT(z) chloroplasts obeyed the same hyperbolic relationship between qE and ΔpH (Fig. 5). It has previously been observed in wild-type Arabidopsis chloroplasts that the absence of zeaxanthin shifts the ΔpH dependence of qE to higher values (12–20). It was interesting to see whether DAD-enhanced qE was sensitive to zeaxanthin so we titrated the level of qE in chloroplasts prepared from dark-adapted wild-type Arabidopsis leaves (WT(v)) (Table 1). As in WT(z) chloroplasts the relationship between qE and ΔpH was unchanged in DAD-treated WT(v) chloroplasts, following the same sigmoidal relationship as in the control (Fig. 5). In DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts virtually no qE was observed below a ΔpH of 2.5, consistent with the behavior of control npq4(z) chloroplasts. However, above this value qE rises to levels approaching the maximum wild-type value in DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 5). The titration curve in npq4(v) chloroplasts, prepared from dark-adapted leaves, was shifted to the right compared with that in npq4(z) chloroplasts, thus higher levels of ΔpH were required to bring about the same level of qE in the former (Fig. 5). Thus in both DAD-treated npq4 and WT chloroplasts zeaxanthin affected the relationship between qE and ΔpH, providing further evidence that DAD-mediated qE occurs by the same mechanism. The extent of sigmoidicity (i.e. the degree of cooperativity, as given by the Hill co-efficient) and the pK (i.e. the proton-antenna association constant for qE) of each titration curve can be quantified by transforming the data with the Hill equation (see “Experimental Procedures”). The pK of qE in DAD-treated WT(z) was 6.2 with a Hill coefficient of 1.36, compared with a pK of 5.0 and a Hill coefficient of 3.7 in WT(v) chloroplasts (Table 2). In the DAD-treated npq4(z) chloroplasts the pK was 4.6 with a Hill coefficient of 4.3, whereas in the npq4(v) chloroplasts the pK was shifted as low as 4.3 with a Hill co-efficient of 7.22. The titration curves thus reveal for the first time that PsbS, like zeaxanthin, controls the relationship between qE and ΔpH. Moreover the effects of zeaxanthin and PsbS were found to be additive.

FIGURE 5.

Titrations of qE versus ΔpH in control WT(z) (red triangles), DAD-treated WT(z) (red circles), control WT(v) (blue triangles), DAD-treated WT(v) (blue circles), control npq4(z) (white triangles), DAD treated npq4(z) (white circles), control npq4(v) (black triangles), and DAD-treated npq4(v) (black circles) chloroplasts. Light intensity was varied between 0 and 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 to achieve different values of ΔpH. Right pointing arrow indicates the enhancement in ΔpH observed above the physiological maximum (dashed line) in the presence of DAD. Data are average of three independent experiments ± S.E. Potential systematic error in estimation of absolute values of ΔpH based on 1000% uncertainty (or 10 times variation) in the total volume of the lumen (1 pH unit) is indicated by the bidirectional arrow above the plots.

TABLE 2.

ΔpH versus qE titration curve fitting parameters in intact Arabidopsis chloroplasts

The titration parameters for the data presented in Fig. 5 were determined by fitting the data with the equation: qE = qEmaxΔpHn/(ΔpHn + ΔpH0n), where qEmax is the theoretical maximum qE, ΔpH is the level of ΔpH at a particular light intensity, ΔpH0 is the level of ΔpH at which qE = 0.5qEmax, and n is the sigmoidicity parameter (Hill coefficient). pK was then estimated by converting ΔpH0 to estimated lumen pH by subtracting from the bulk pH (8.0).

| Material | Hill coefficient | Estimated pK | qEmax (experimental) | qEmax (theoretical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| WT(z) | 1.36 | 6.2 | 0.62 ± 0.2 | 0.78 |

| WT (v) | 3.69 | 5.0 | 0.48 ± 0.2 | 0.71 |

| npq4(z) | 0.25 ± 0.1 | |||

| npq4(v) | 0.10 ± 0.1 | |||

| DAD treated | ||||

| WT(z) | 1.30 | 6.4 | 0.73 ± 0.2 | 0.87 |

| WT(v) | 2.83 | 5.28 | 0.72 ± 0.2 | 0.85 |

| npq4(z) | 4.29 | 4.57 | 0.69 ± 0.2 | 0.86 |

| npq4(v) | 7.22 | 4.31 | 0.64 ± 0.2 | 0.67 |

Previous studies have shown that a lumen pH of 5.0 and below has damaging effects on the oxygen-evolving complex of PSII and on plastoquinone oxidation by the cytochrome b6f complex (49, 50). Any such negative effects of low lumen pH would be predicted to suppress the level of qP during illumination. Contrary to this prediction qP was actually elevated in the presence of the DAD-mediated NPQ in npq4(z) and WT(z) chloroplasts relative to the control samples (Fig. 3). Therefore, we checked whether the 9-AA quenching method provides a reasonable estimate of lumen pH by titrating the relaxation of qE in WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts with acid. It has previously been demonstrated that qE can be sustained by lowering the pH of the bulk medium in spinach thylakoids, i.e. preventing the escape of protons from the lumen (15). Here we allowed qE to form in DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts and then added an aliquot of acid to change the bulk pH of the medium to a chosen value between pH 8.0 and pH 3.7. The actinic illumination was then immediately turned off. When the bulk pH was lowered to 4.0 virtually all of the qE was maintained in the dark in the DAD-treated WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts (Fig. 6, A and B). However, when the bulk pH was lowered to 5.2 the WT(z) chloroplasts still maintained over 50% of the maximum qE in the dark (Fig. 6A), however, in npq4(z) virtually all of the qE was absent (Fig. 6B). By repeating these experiments across a range of pH values qE titration curves were determined for WT(z), WT(v), npq4(z), and npq4(v) chloroplasts (Fig. 7A). The pK values determined from these titration curves compared favorably with those calculated from the 9-AA quenching data with a deviation of no more than 0.3 pH units (cf. Tables 2 and 3). This fact is emphasized in Fig. 7A by overlaying the acid titration data for each sample with the respective fits from Fig. 5. The fact that qE in npq4(z) chloroplasts could be maintained in the dark only at pH 4.0 suggests that the level of ΔpH induced by DAD is indeed as high as 4.0 (Fig. 6B). When the bulk pH of WT or npq4 chloroplasts was lowered to 3.7, less qE was maintained in the dark indicating that the system may be denatured at these values (Fig. 7A). We also investigated the effect of the pH of the bulk medium on the level of qP in the dark in WT(z) and npq4(z) chloroplasts following 5 min illumination (Fig. 7B). Consistent with previously published data (38, 39) we found that the onset of damage to PSII (quantified by qP) began below a bulk pH of 5.0. The fall in qP was particularly sharp between pH 4.0 and 3.5 falling from 0.8 to 0.4 (Fig. 7B). In contrast in samples where only the lumen pH is low during illumination (due to ΔpH formation) no significant fall in qP levels occurred (Fig. 7B). These data indicate that low bulk pH has more serious consequences for PSII activity compared with low lumen pH alone.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of lowering the pH (at time point shown by arrow marked +HCL) of the bulk medium on qE relaxation in the dark following 5 min illumination to induce maximum qE in DAD-treated (A) WT(z) and (B) npq4(z) chloroplasts. Light intensity in all cases was 350 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. Data are average of three independent experiments ± S.E.

FIGURE 7.

A, titrations of qE maintained in the dark versus bulk pH in DAD-treated WT(z) (red circles), DAD-treated WT(v) (blue circles), DAD-treated npq4(z) (white circles), and DAD-treated npq4(v) (black circles) chloroplasts. Solid lines are fits of the data presented in Fig. 5 to show close agreement between the two sets of data. B, effect of lowering the pH of the bulk medium on qP levels in the dark following 5 min illumination to induce maximum qE in DAD-treated WT(z) (white circles) and npq4(z) (black circles) chloroplasts. Shown for comparison is the qP level in the dark following 5 min illumination where only the lumen pH level fell below 8.0 (due to ΔpH formation) during illumination, DAD-treated WT(z) (white squares) and npq4(z) (black squares) chloroplasts.

TABLE 3.

pH versus qE titration curve fitting parameters in intact Arabidopsis chloroplasts

The titration parameters for the data presented in Fig. 7 were determined by fitting the data with the equation: qE = qEmaxpHn/(pHn + pH0n), where qEmax is the theoretical maximum qE, pH is the pH of the buffer medium, pH0 is the pH level at which qE = 0.5 qEmax, and n is the sigmoidicity parameter (Hill coefficient).

| Material | Hill coefficient | Estimated pK | qEmax (experimental) | qEmax (theoretical) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAD treated | ||||

| WT(z) | 1.75 | 6.29 | 0.76 ± 0.2 | 0.81 |

| WT(v) | 3.55 | 5.12 | 0.61 ± 0.2 | 0.69 |

| npq4(z) | 4.42 | 4.66 | 0.66 ± 0.2 | 0.87 |

| npq4(v) | 5.44 | 4.21 | 0.45 ± 0.2 | 0.66 |

DISCUSSION

DAD-induced CEF around PSI enhanced ΔpH levels in Arabidopsis chloroplasts from a value of 2.4 in the controls where only natural electron acceptors were present up to 4.1. The ability of far-red light to induce significant levels of ΔpH in the presence of DAD confirmed the involvement of PSI-driven CEF. However, treatment of chloroplasts with the PSII inhibitor DCMU confirmed that maximal levels of ΔpH and qE were only observed when LEF and CEF were operating in tandem. CEF-driven ΔpH has previously been shown to modulate qE in tobacco and Arabidopsis (7, 51). Enhanced levels of ΔpH allowed us to test the hypothesis that PsbS acted as a catalyst of qE by affecting the ΔpH sensitivity of the process. Wild-type levels of qE were observed for the first time at a ΔpH level of 4.0 in intact npq4(z) chloroplasts. Acid titration of qE relaxation confirmed that it required a pH of 4.0 to prevent any significant relaxation of qE in npq4, confirming the ability of DAD to induce very high lumen acidification. It is important to note that calculations of lumen pH and ΔpH in this article require an estimate of the lumen volume. For this end we used the values calculated by Avron and co-workers (52) on lettuce chloroplasts. Indeed, we note that variations in the lumen volume do not affect dramatically the calculated values of ΔpH. Thus, for example, if 9-AA fluorescence is 50% quenched and a lumen volume of 0.5 μl/ml is assumed, the ΔpH will be 3.3. If the volume is 1.0 μl/ml, the actual ΔpH will be 3.0, only 0.3 pH units lower. Nevertheless, the systematic error in the estimation of the lumen volume could be even higher, therefore the pH calculation can potentially have 1 unit or so of error (as shown in Fig. 5). The cause of this problem could come from the fact that chloroplast intactness and hence thylakoid lumen volume is likely to display significant variability depending upon isolation procedures. Precisely for this reason we undertook an additional set of measurements using the stroma acidification titrations to prevent qE recovery (Figs. 6 and 7) and demonstrated a close consistency in the calculated pH requirement for qE (pK) in both methodologies and are also broadly consistent with estimates made by electrochromic shift (ΔA515) measurements (48).

The qE generated in npq4 chloroplasts in the presence of DAD displayed the same features normally associated with the process in the wild-type. Like qE, it was sensitive to zeaxanthin, accompanied by the qE-related absorption changes in the Soret band (often known as ΔA535), and quenched the level of fluorescence when all PSII reaction centers were in the open state (Fo state) consistent with antenna based quenching. These “qE-like” features distinguish the DAD-mediated quenching from PSII donor-side quenching mechanisms induced by low pH in the presence of strong oxidants such as ferredoxin (15, 53, 54). Our data also provide interesting insights into the inactivation of the PSII OEC by low pH. When the pH of the bulk medium was lower than 5.0 a significant inactivation of PSII occurred (as determined by qP levels) consistent with previous studies (49, 50). High ΔpH alone, however, as seen in DAD-treated chloroplasts did not appear to inactivate PSII. Moreover, the qE in npq4 chloroplasts actually reduced the excitation pressure on PSII protecting it from the light-induced damage that was observed in control npq4 chloroplasts.

An understanding of how different molecules affect the relationship between qE and ΔpH can provide clues as to their function. Our titrations reveal the additive nature of the effect of zeaxanthin and PsbS on the pKa of protonable residues associated with qE. The apparent pKa of amino acids has been shown to strongly depend upon their environment (55–57). Hydrogen bonding, steric hindrance, and the di-electric constant of the environment can all affect the pKa of amino acids (55–57). For instance the pKa of the carboxyl group on aspartate can be as low as 2.4 when exposed to water due to hydrogen bonding, whereas in hydrophobic environments the pKa can be as high as 6.4 (56). The ability of xanthophylls to affect the pKa of lumen-facing amino acids is not surprising given their essential role in shaping LHC tertiary and quaternary structures (58, 59). LHC complexes bind 4 different types of xanthophylls, the hydrophobic character of which has been shown to vary due to their differing chemical structures (60). The most hydrophobic xanthophyll zeaxanthin was found to promote LHC aggregation and shift the pK of in vitro quenching to more alkaline values (24, 61). There is also biochemical evidence that zeaxanthin can influence the isoelectric point of LHC complexes (62). The more polar xanthophylls, such as violaxanthin, had the opposite effect, inhibiting aggregation and shifting the pK of quenching to more acid values (24, 61). Recently, the pK of qE in various xanthophyll biosynthetic mutants was also found to be correlated with xanthophyll hydrophobicity (63). Compared with zeaxanthin the effect of PsbS on the pKa of protonable residues associated with qE is harder to understand.

Biochemical evidence has recently been provided that the PSII antenna is reorganized in response to ΔpH, altering the interactions between LHC subunits such that a part of the PSII-LHCII supercomplex containing CP24, CP29, and LHCII dissociates (64, 65). This reorganization/aggregation of the PSII antenna in high light was shown to depend upon the presence of PsbS and was enhanced by zeaxanthin (64, 65). We suggest that the ability of PsbS to affect the pK of qE is associated with its influence on the PSII organization. There is evidence that grana membranes are much more rigidly organized with a higher proportion of ordered PSII-LHCII semi-crystalline arrays (37). The altered organization increases the concentration of Mg2+ cations required for the reassembly of the PSII-LHCII supercomplex in the fluorescent state and restacking of the grana membranes (36). It seems that the reverse is also true, in the absence of PsbS more protons are required to reorganize PSII and LHCII into the dissipative state. We suggest that without PsbS, reorganization of PSII and LHCII occurs only very slowly, explaining the slowly forming NPQ phenotype of control npq4 plants (32). However, the energetic barrier imposed by the more rigid organization of PSII-LHCII in the absence of PsbS can be overcome by higher levels of protonation. Our data are therefore consistent with earlier suggestions that PsbS acts as a catalyst of qE formation (17, 33, 34). Changes in subunit interactions and/or stabilities of different conformations are predicted by the allosteric model of Monod et al. (66) to alter the cooperativity of substrate (in this case proton) binding, exactly as observed in npq4 chloroplasts. In control chloroplasts where no artificial electron acceptors were added, the maximum ΔpH we observed was 2.4, consistent with the moderate lumen pH independently estimated in vivo (21). Thus, by promoting reorganization of the PSII-LHCII supercomplex and aggregation of LHCs, PsbS and zeaxanthin work synergistically to shift the pK of qE by nearly 2 pH units allowing almost maximal photoprotection at physiologically attainable levels of lumen pH.

This work provides a plausible explanation for the involvement of PsbS in qE regulation. The mechanism of PsbS action is explained by its synergistic control with zeaxanthin of the proton-antenna association constant, pK, via regulation of the interconnected phenomena of LHC antenna reorganization/aggregation and hydrophobicity. The findings in this article thus mark another important step toward understanding this vital photoprotective process.

Acknowledgment

We thank Krishna Niyogi (Berkeley, CA) for providing the seeds of the Arabidopsis mutants used in this study.

The work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council UK and Engineering and Environmental Sciences Research Council UK research grants (to A. V. R.).

- NPQ

- nonphotochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching

- PSI

- photosystem I

- PSII

- photosystem II

- LHCII

- light harvesting antenna complex of photosystem II

- ΔpH

- proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane

- qE

- ΔpH-dependent portion of NPQ

- (z)

- zeaxanthin containing chloroplasts

- (v)

- chloroplasts containing no zeaxanthin

- pK

- proton antenna association constant

- LED

- light emitting diode

- 9-AA

- 9-aminoacridine

- DAD

- diaminodurene

- PMS

- phenazine metasulfate

- DCMU

- 3-(3′,4′-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea

- CEF

- cyclic electron flow

- LEF

- linear electron flow.

REFERENCES

- 1. Horton P., Ruban A. V., Walters R. G. (1996) Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 47, 655–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Holt N. E., Fleming G. R., Niyogi K. K. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 8281–8289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nelson N., Ben-Shem A. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 971–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kramer D. M., Avenson T. J., Edwards G. E. (2004) Trends Plant Sci. 9, 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arnon D. I., Allen M. B., Whatley F. R. (1954) Nature 174, 394–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shikanai T. (2007) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58, 199–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munekage Y., Hojo M., Meurer J., Endo T., Tasaka M., Shikanai T. (2002) Cell 110, 361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walters R. G., Ruban A. V., Horton P. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem. 226, 1063–1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walters R. G., Ruban A. V., Horton P. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 14204–14209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li X. P., Gilmore A. M., Caffarri S., Bassi R., Golan T., Kramer D., Niyogi K. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 22866–22874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jahns P., Latowski D., Strzalka K. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787, 3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rees D., Young A. J., Noctor G., Britton G., Horton P. (1989) FEBS Lett. 256, 85–90 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Horton P., Ruban A. V., Rees D., Pascal A. A., Noctor G., Young A. J. (1991) FEBS Lett. 292, 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noctor G., Rees D., Young A. J., Horton P. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1057, 320–330 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rees D., Noctor G., Ruban A. V., Crofts J., Young A. J., Horton P. (1992) Photosynth. Res. 31, 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noctor G., Ruban A. V., Horton P. (1993) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1183, 339–344 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Horton P., Ruban A. V., Wentworth M. (2000) Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355, 1361–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruban A. V., Wentworth M., Horton P. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 9896–9901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pérez-Bueno M. L., Johnson M. P., Zia A., Ruban A. V., Horton P. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582, 1477–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joliot P. A., Finazzi G. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12728–12733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kramer D. M., Sacksteder C. A., Cruz J. A. (1999) Photosynth. Res. 60, 151–163 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Demmig-Adams B., Adams W., 3rd, Heber U., Neimanas S., Winter K., Krüger A., Czygan F. C., Bilger W., Björkman O. (1990) Plant Physiol. 92, 292–301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Niyogi K. K., Grossman A. R., Björkman O. (1998) Plant Cell 10, 1121–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ruban A. V., Horton P. (1999) Plant Physiol. 119, 531–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li X. P., Björkman O., Shih C., Grossman A. R., Rosenquist M., Jansson S., Niyogi K. K. (2000) Nature 403, 391–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li X. P., Muller-Moule P., Gilmore A. M., Niyogi K. K. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 15222–15227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Külheim C., Agren J., Jansson S. (2002) Science 297, 91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aspinall-O'Dea M., Wentworth M., Pascal A., Robert B., Ruban A., Horton P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16331–16335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bonente G., Howes B. D., Caffarri S., Smulevich G., Bassi R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 8434–8445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crouchman S., Ruban A., Horton P. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 2053–2058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zia A., Johnson M. P., Ruban A. V. (2011) Planta, doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1380-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson M. P., Ruban A. V. (2010) Plant J. 61, 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dominici P., Caffarri S., Armenante F., Ceoldo S., Crimi M., Bassi R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22750–22758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horton P., Johnson M. P., Perez-Bueno M. L., Kiss A. Z., Ruban A. V. (2008) FEBS J. 275, 1069–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dekker J. P., Boekema E. J. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1706, 12–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kiss A. Z., Ruban A. V., Horton P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3972–3978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kereïche S., Kiss A. Z., Koucril R., Boekema E., Horton P. (2010) FEBS Lett. 584, 754–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wraight C. A., Crofts A. R. (1970) Eur. J. Biochem. 17, 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mills J., Barber J. (1975) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 170, 306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rees D., Noctor G. D., Horton P. (1990) Photosynth. Res. 25, 199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Amesz J., Fork D. C. (1967) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 143, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hauska G. A., Prince R. C. (1974) FEBS Lett. 41, 35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun G., Driesenaar A. R., Malkin S., Trebst A. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1100, 58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnson M. P., Pérez-Bueno M. L., Zia A., Horton P., Ruban A. V. (2009) Plant Physiol. 149, 1061–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schuldiner S., Rottenberg H., Avron M. (1972) Eur. J. Biochem. 25, 64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson M. P., Havaux M., Triantaphylidès C., Ksas B., Pascal A. A., Robert B., Davison P. A., Ruban A. V., Horton P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22605–22618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Porra R. J., Thompson W. A., Kriedemann P. E. (1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 975, 384–394 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Takizawa K., Cruz J. A., Kanazawa A., Kramer D. M. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 1233–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Krieger A., Weis E. (1993) Photosynth. Res. 37, 117–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Spetea C., Hidge E., Vass I. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1318, 275–283 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yamamoto H., Kato H., Shinzaki Y., Horiguchi S., Shikanai T., Hase T., Endo T., Nishioka M., Makino A., Tomizawa K., Miyake C. (2006) Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1355–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rottenberg H., Grunwald T., Avron M. (1972) Eur. J. Biochem. 25, 54–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Crofts J., Horton P. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1058, 187–193 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krieger A., Moya I., Weis E. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1102, 167–176 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thurlkill R. L., Grimsley G. R., Scholtz J. M., Pace C. N. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 362, 594–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mehler E. L., Fuxreiter M., Simon I., Garcia-Moreno E. B. (2002) Proteins Struct. Funct. Genet. 48, 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li H., Robertson A. D., Jensen J. H. (2004) Proteins 55, 689–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paulsen H. (1999) in The Photochemistry of Carotenoids (Frank H. A., Young A. J., Britton G., Cogdell R. eds) pp. 123–135, Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lokstein H., Tian L., Polle J. E., DellaPenna D. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1553, 309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ruban A. V., Horton P., Young A. J. (1993) J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 21, 229–234 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ruban A. V., Phillip D., Young A. J., Horton P. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 7855–7859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dall'Osto L., Caffarri S., Bassi R. (2005) Plant Cell 17, 1217–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ruban A. V., Johnson M. P. (2010) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 504, 78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Betterle N., Ballottari M., Zorzan S., de Bianchi S., Cazzaniga S., Dall'osto L., Morosinotto T., Bassi R. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15255–15266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Johnson M. P., Goral T. K., Duffy C. D., Brain A. P., Mullineaux C. W., Ruban A. V. (2011) Plant Cell, doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J. P. (1965) J. Mol. Biol. 12, 88–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]