Abstract

Background

The copper (Cu) transporter (COPT/Ctr) gene family has an important role in the maintenance of Cu homeostasis in different species. The rice COPT-type gene family consists of seven members (COPT1 to COPT7). However, only two, COPT1 and COPT5, have been characterized for their functions in Cu transport.

Results

Here we report the molecular and functional characterization of the other five members of the rice COPT gene family (COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7). All members of the rice COPT family have the conserved features of known COPT/Ctr-type Cu transporter genes. Among the proteins encoded by rice COPTs, COPT2, COPT3, and COPT4 physically interacted with COPT6, respectively, except for the known interaction between COPT1 and COPT5. COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 cooperating with COPT6 mediated a high-affinity Cu uptake in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant that lacked the functions of ScCtr1 and ScCtr3 for Cu uptake. COPT7 alone could mediate a high-affinity Cu uptake in the yeast mutant. None of the seven COPTs alone or in cooperation could complement the phenotypes of S. cerevisiae mutants that lacked the transporter genes either for iron uptake or for zinc uptake. However, these COPT genes, which showed different tissue-specific expression patterns and Cu level-regulated expression patterns, were also transcriptionally influenced by deficiency of iron, manganese, or zinc.

Conclusion

These results suggest that COPT2, COPT3, and COPT4 may cooperate with COPT6, respectively, and COPT7 acts alone for Cu transport in different rice tissues. The endogenous concentrations of iron, manganese, or zinc may influence Cu homeostasis by influencing the expression of COPTs in rice.

Background

Copper (Cu) is an essential micronutrient for living organisms. Cu, as a cofactor in proteins, is involved in a wide variety of physiological processes. Cu has an impact on the development of the nervous system in animals and humans; deficiency of this micronutrient causes Menkes syndrome in humans [1,2]. In plants, Cu is associated with various physiological activities, such as photosynthesis, mitochondrial respiration, superoxide scavenging, cell wall metabolism, and ethylene sensing [3]. Cu deficiency causes diverse abnormal phenotypes in plants, including decreased growth and reproductive development, distortion of young leaves, and insufficient water transport [4]. Cu can also be a toxic element when present in excess by generating hydroxyl radicals that damage cells at the level of nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids or by reacting with thiols to displace other essential metals in proteins [4]. Wilson disease in humans is caused by the accumulation of Cu in the liver and brain [1]. The most common symptom of Cu toxicity in plants is chlorosis of vegetative tissues due to the dysfunction of photosynthesis [4].

To deal with this dual nature of Cu, plants, as well as other organisms, have developed a sophisticated homeostatic network to control Cu uptake, trafficking, utilization, and detoxification or exportation [5,6]. A main step in the control of Cu homeostasis is its uptake through the cell membrane. Different types of transporter proteins that can mediate Cu uptake have been reported. The major group is the COPT (COPper Transporter)/Ctr (Copper transporter) proteins, which belong to multiple protein families in different organisms [7]. The P-type adenosine triphosphate pump is another type of transporter for moving Cu from cytosol into organelles in humans and plants [8,9]. It has also been reported that other metal transporters can transport Cu into cells. For example, YSL1 and YSL3 of the OPT/YSL iron (Fe) transporter family can transport Cu from leaves to seeds in Arabidopsis [10], and ZIP2 and ZIP4 of the ZIP zinc (Zn) transporter family seem to transport Cu in Arabidopsis [11].

The Cu-uptake function of COPT/Ctr proteins was described primarily in baker's yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [12]. Soon afterward, COPT/Ctr proteins involved in Cu transport were characterized in different organisms, for example: ScCtr1, ScCtr2, and ScCtr3 in S. cerevisiae [12-15]; AtCOPT1, AtCOPT2, AtCOPT3, AtCOPT4, and AtCOPT5 in Arabidopsis thaliana [13,16]; hCtr1 and hCtr2 in humans (Homo sapiens) [17,18]; SpCtr4, SpCtr5, and SpCtr6 in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) [19-21]; mCtr1 in mouse (Mus musculus) [22]; PsCtr1 in lizard (Podarcis sicula) [23]; Ctr1A, Ctr1B, and Ctr1C in Drosophila melanogaster [24]; DrCtr1 in bony fish (Danio rerio) [25]; CaCtr1 in ascomycete Colletotrichum albicans [26]; CgCtr2 in ascomycete C. gloeosporioides [27]; CrCTR1, CrCTR2, CrCTR3, and CrCOPT1 in green algae (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) [28]; and OsCOPT1 and OsCOPT5 in rice (Oryza sativa) [29]. COPT/Ctr-like proteins also occur in zebrafish [15], ascomycete Neurospora crassa [30], and mushroom Coprinopsis cinerea [31], although their functions in Cu uptake remain to be determined.

The alignment of COPT/Ctr family members from different species highlights domains that are structurally conserved and probably functionally important during the evolution of these proteins. According to bioinformatic analyses, all COPT/Ctr proteins contain three putative transmembrane regions [7]. Characterized COPT/Ctr proteins are either plasma membrane proteins that transport Cu from extracellular spaces into cytosol or vacuoles or lysosome membrane proteins that deliver Cu from vacuoles or lysosomes to the cytosol [15,18,20,32]. COPT/Ctr proteins can form a homodimer, homotriplex [22,33], or heterocomplex with themselves or each other [19,21] or form a heterocomplex with another protein that is associated with Cu transport [29]. A structural model has been proposed for the function of human homotrimeric hCtr1 in which Cu(I) first coordinates to the methionine-rich motif in the hCtr1 extracellular amino (N)-terminus and then a conserved methionine residue upstream of the first transmembrane domain is essential for Cu transport [33,34]. The homotriplex is thought to provide a channel for passage of Cu across the lipid bilayer [35]. The conserved paired cysteine residues in the cytoplasmic carboxyl (C)-terminus of yeast ScCtr1 serve as intracellular donors for Cu(I) for its mobilization to the Cu chaperones [36].

Studies have revealed that the expression of COPT/Ctr genes is controlled by environmental Cu level in different species [7,29,37]. In general, they are transcriptionally up-regulated in response to Cu deprivation and down-regulated in response to Cu overdose. The functions of COPT/Ctr proteins are also influenced by other factors. For example, the human hCtr1-mediated Cu transport is stimulated by extracellular acidic pH and high K+ concentration [22].

The COPT family of rice (Oryza sativa L.) consists of seven members, COPT1 to COPT7. COPT1 and COPT5 can form homodimers or a heterodimer. The two COPTs, but not other rice COPTs, bind to different sites of rice XA13 protein, which is a susceptible protein to pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) [29]. Expression of COPT1, COPT5, or XA13 alone or coexpression of any two of the three proteins could not complement the phenotype of yeast S. cerevisiae mutant, which lacked the functions of ScCtr1 and ScCtr3 for Cu uptake; only coexpression of all three proteins complemented the mutant phenotype [29]. However, it is unknown whether rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT5 are also involved in Cu transport. In this study, we analyzed the putative Cu-uptake functions of the five rice COPTs using a yeast ctr mutant. We also analyzed the spatiotemporal, tissue-specific, metal-responsive, and pathogen-responsive expression patterns of rice COPTs. The results suggest that rice COPTs are transcriptionally influenced by multiple factors. Except for COPT1 and COPT5, other COPTs may function alone or cooperatively to mediate Cu transport in different rice tissues.

Methods

Plant treatment

To study the effect of Cu on gene expression, four-leaf seedlings of rice variety Zhonghua 11 (Oryza sativa ssp. japonica) were grown in hydroponic culture containing standard physiological Cu (0.2 mM), manganese (Mn; 0.5 mM), Fe (0.1 mM), and Zn (0.5 mM) or overdose Cu (50 mM) as described previously [29]. To induce a deficiency of Cu, Mn, Fe, or Zn, plants were grown in the culture media lacking Cu, Mn, Fe, or Zn for 2 weeks.

To analyze the effect of bacterial infection on gene expression, plants were inoculated with Philippine Xoo strain PXO61 (race 1) or PXO99 (race 6) at the booting (panicle development) stage by the leaf-clipping method [38]. The 2-cm leaf fragments next to bacterial infection sites were used for RNA isolation.

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression was analyzed as described previously [29]. In brief, total RNA was isolated from different tissues of rice variety Zhonghua 11 using TRIzol (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The concentration of RNA was measured with a NANODROP 1000 Spectrophtometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA); the A260/A280 ratio was generally between 1.8 and 2.0; RNA concentration was approximately 60 μg/100 mg fresh rice tissue. An aliquot (5 μg) of RNA was treated with 1 unit of DNase I (Life Technologies Corporation) in a 20-μl volume for 15 minutes to remove contaminating DNA and then used for quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis. The RT step was performed in a 20-μl volume containing 5 μg of RNA, 100 ng oligo(dT)15 primer, 2 nmol dNTP mix, and 100 unit of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The cDNA was stored at -20°C. The qPCR was performed using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) on the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Gene-specific PCR primers are listed in Additional file 1, Table S1. The expression level of actin gene was first used to standardize the RNA sample for each qRT-PCR. The expression level relative to control was then presented. Each qRT-PCR or RT-PCR assay was repeated at least twice with similar results, with each repeat having three replicates.

Plasmid constructs

The full-length cDNAs of rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7 genes were obtained by RT-PCR using gene-specific primers (Additional file 1, Table S2). The cDNAs of COPT2, COPT3, and COPT6 were subcloned into the BamHI/EcoRI sites of p413GPD(+His) vector and the cDNAs of COPT4 and COPT7 were subcloned into the SpeI/EcoRI sites of p413GPD(+His) separately [39]. The cDNA of S. cerevisiae Ctr1 was amplified from yeast BY4741 using gene-specific primers (Additional file 1, Table S2) and was inserted into the SpeI/EcoRV sites of p413GPD(+His). All the cDNA sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The p413GPD(+His) plasmids carrying respective COPT1 and COPT5 were as reported previously [29].

Functional complementation analyses in yeast

To study the putative function of genes in Cu transport, plasmid DNA was transformed into the yeast ctr1Δctr3Δ double-mutant strain MPY17 (MATα, ctr1::ura3::kanR, ctr3::TRP1, lys2-801, his3), which lacked the Ctr1 and Ctr3 for high-affinity Cu uptake, by the lithium acetate procedure [14]. This mutant strain cannot grow on ethanol/glycerol medium (YPEG: 1% yeast extract, 2% Bactopeptone, 2% ethanol, 3% glycerol, 1.5% agar) because it possesses a defective mitochondrial respiratory chain due to the inability of cytochrome c oxidase to obtain its Cu factor [14]. The transformed yeast cells were grown in SC-His to OD600nm = 1.0. Several 10-fold diluted clones were plated as drops on selective media without or with supplement of Cu (CuSO4). Plates were incubated for 3 to 6 days at 30°C.

To study the putative functions of genes in Fe or Zn transport, plasmid DNA was transformed into the yeast fet3fet4DEY1453 or zrt1zrt2ZHY3 mutants or the wild-type strain DEY1457 by the same lithium acetate procedure described above. The fet3fet4DEY1453 double mutant (MATα trp1 ura3 Δfet3::LEU2 Δfet4::HIS3) lacked the Fet3 and Fet4 for Fe uptake [40]. The zrt1zrt2ZHY3 double mutant (MATα ade6 can1 his3 leu2 lys2 trp1 ura3 zrt1::LEU2 zrt2::HIS3 Δfet3::LEU2 Δfet4::HIS3) lacked the Zrt1 and Zrt2 for Zn uptake [41,42]. Yeast cells were grown in YPD (yeast extract-peptone) medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) to OD600nm = 1.0. Several 10-fold diluted clones were plated as drops on selective media containing 50 mM bathophenanthroinedisulfonic acid disodium (BPDS) without or with supplement of Fe (FeSO4), or containing 1 mM EDTA without or with supplement of Zn (ZnSO4). BPDS was a synthetic chelate of Fe and EDTA was a synthetic chelate of Zn. Plates were incubated for 3 to 6 days at 30°C. The yeast strains transformed with empty vector were the negative controls.

Protein-protein interaction in yeast cells

The split-ubiquitin system was used to investigate the interaction of rice COPTs. The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) Membrane Protein System Kit (MoBiTec, Goettingen, Germany) was used for this type of assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. In this system, COPT proteins fused with both the C-terminal half of the ubiquitin protein (Cub) and the mutated N-terminal half of the ubiquitin protein (NubG). Cub could not interact with NubG. When COPT proteins interacted, Cub and NubG were forced into close proximity, resulting in the activation of reporter gene. Each COPT full-length cDNA amplified from rice variety Zhonghua 11 using gene-specific primers (Additional file 1, Table S3) was cloned into both vector pBT3-SUC and vector pPR3-SUC; the 3' ends of COPT cDNAs were fused with the 5' end of the sequence encoding NubG. The insertion fragments of all the vectors were examined by DNA sequencing. Cub and NubG fusion constructs were co-transformed into host yeast strain NMY51. Interaction was determined by the growth of yeast transformants on medium lacking His or Ade and also by measuring β-galactosidase activity.

Protein topology analyses

The localization of rice COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 protein in S. cerevislae was analyzed by fusion of the COPT gene with the green fluorescence protein (GFP) gene using gene-specific primers (Additional file 1, Table S4). Plasmid harboring the fusion gene was transformed into the S. cerevislae mutant MPY17 [29]. The fluorescence signal was visualized with a LEICA DM4000B fluorescent microscope.

Sequence analysis

Multiple-sequence alignment of amino acid sequences was achieved with ClustalW program http://www.expasy.ch/tools/#align[43]. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed in the ClustalX program based on the full sequences of the proteins with default parameters [44]. The transmembrane domains of proteins were predicted using the TMHMM program http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/.

Results

Rice COPT family has all the conserved features of known COPT/Ctr-type Cu transporter genes

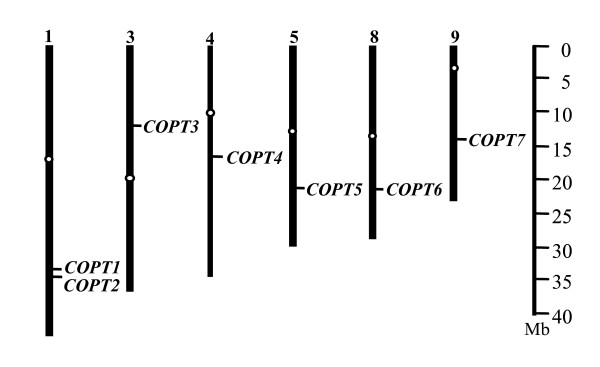

Analysis of the genomic sequences of rice variety Nipponbare (Oryza sativa ssp. japonica) revealed seven genes, COPT1 (Os01g56420; GenBank accession number GQ387494), COPT2 (Os01g56430; HQ833653), COPT3 (Os03g25470; HQ833654), COPT4 (Os04g33900; HQ833655), COPT5 (Os05g35050; GQ387495), COPT6 (Os08g35490; HQ833656), and COPT7 (Os09g26900; HQ833657), that showed sequence homology with COPT or Ctr genes from other species [29]. The seven COPTs are located on six of the 12 rice chromosomes (1, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9) (Figure 1). Based on the annotation of Rice Genome Annotation Project (RGAP; http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/), all seven genes are intron-free. The seven genes are G- and C-rich consisting more than 72% G and C.

Figure 1.

Chromosomal locations of rice COPT genes. The centromere of each chromosome is indicated with a white circle.

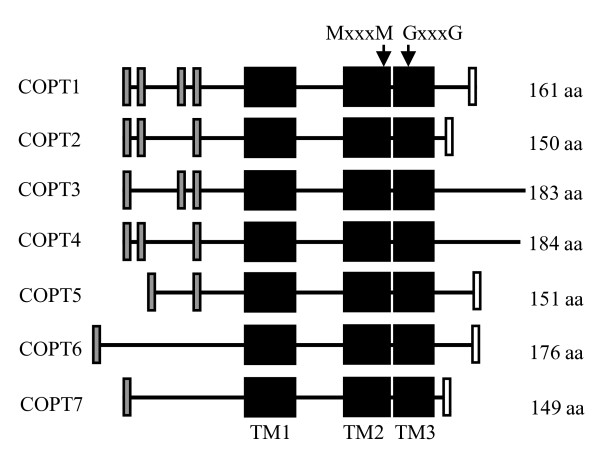

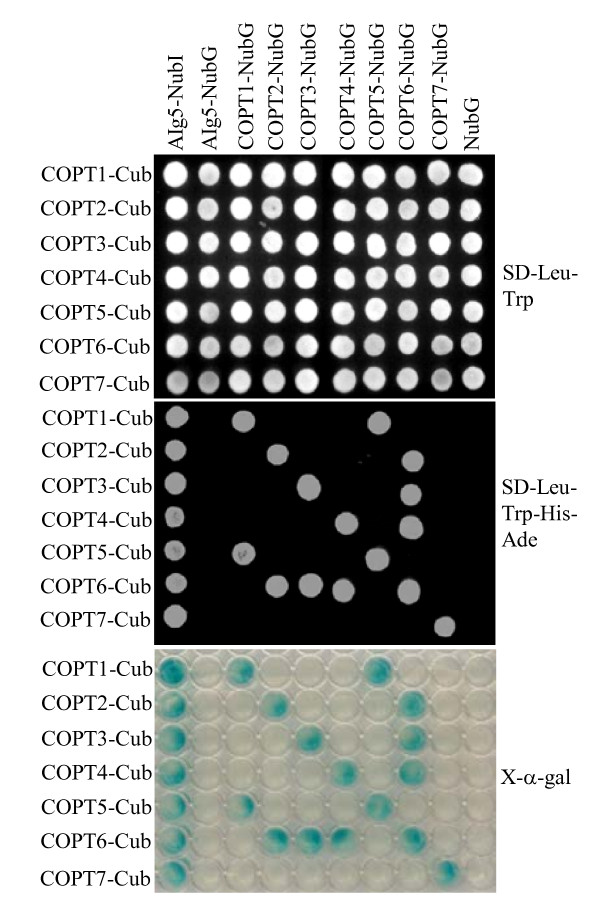

The rice COPT proteins share 35% to 64% sequence identity and 47% to 73% sequence similarity each other (Table 1) and have a similar structure (Figure 2), which is similar to COPT/Ctr proteins in other species [11]. The central domains of rice COPTs are three transmembrane (TM) regions, TM1, TM2, and TM3 (Figure 2). TM1 and TM2 in the COPT/Ctr proteins of other species are separated by a cytoplasmic loop [7,45]. Only a few residues separate TM2 and TM3 of rice COPTs (Figure 2). It has been reported that a short loop connecting TM2 and TM3 is essential for function and it enforces a very tight spatial relationship between these two TM segments at the extracellular side of plasma membrane [46]. Rice TM2 harbors the MxxxM (x representing any amino acid) motif and TM3 contains the GxxxG motif, together forming the characteristic MxxxM-x12-GxxxG motif of COPT/Ctr proteins [46]. COPT/Ctr proteins usually have an extracellular N-terminus and a cytoplasmic C-terminus; the N-terminus is generally rich in conserved methionine-rich motifs, which are important for low level of Cu transport; the C-terminus tends to contain cysteine- and/or histidine-rich motifs, such as CxC, which binds Cu ions and transfers them to cytosolic Cu chaperones [45,47]. All these key features are present in rice COPTs. COPT1 and COPT5 have cytoplasmic C-termini [29]. The interactions of COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7 with Alg5, a TM protein, in yeast cells using a split-ubiquitin system for integral membrane proteins [48] suggests that the other five rice COPTs also have cytoplasmic C-termini (Figure 3). All seven COPTs have one to four MxM or MxxM motifs at N-termini (Figure 2). The CC motif has been detected in rice COPT1, COPT2, and COPT5 and CxC motif in rice COPT6 and COPT7 at the C-termini (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Analysis of amino acid sequence identity/similarity (%) among members of rice COPT family

| COPT1 | COPT2 | COPT3 | COPT4 | COPT5 | COPT6 | COPT7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPT1 | 100/100 | 64/71 | 47/54 | 49/57 | 64/71 | 58/62 | 37/51 |

| COPT2 | 100/100 | 48/56 | 45/53 | 64/73 | 60/66 | 38/50 | |

| COPT3 | 100/100 | 59/61 | 50/58 | 57/61 | 56/67 | ||

| COPT4 | 100/100 | 54/61 | 60/62 | 36/47 | |||

| COPT5 | 100/100 | 56/64 | 35/47 | ||||

| COPT6 | 100/100 | 50/60 | |||||

| COPT7 | 100/100 |

Figure 2.

The structure of rice COPT proteins. Lines represent the protein chains. Black boxes represent predicted transmembrane (TM1, TM2, TM3) regions. Gray boxes indicate the positions of MxM or MxxM motifs and white boxes indicate the positions of CC or CxC motifs.

Figure 3.

Analyses of the interactions of rice COPTs protein by split-ubiquitin system. The growth of yeast cells on selective medium and the expression of reporter protein a-galactosidase (X-a-gal) indicate the homomeric or heteromeric interactions of COPTs. AIg5, a transmembrane protein with C terminal in the cytoplasm; NubI, N-terminal half of ubiquitin protein; NubG, mutated N-terminal half of ubiquitin protein; Cub, C-terminal half of ubiquitin protein; Leu, leucine; Trp, tryptophan; His, histidine; Ade, adenine.

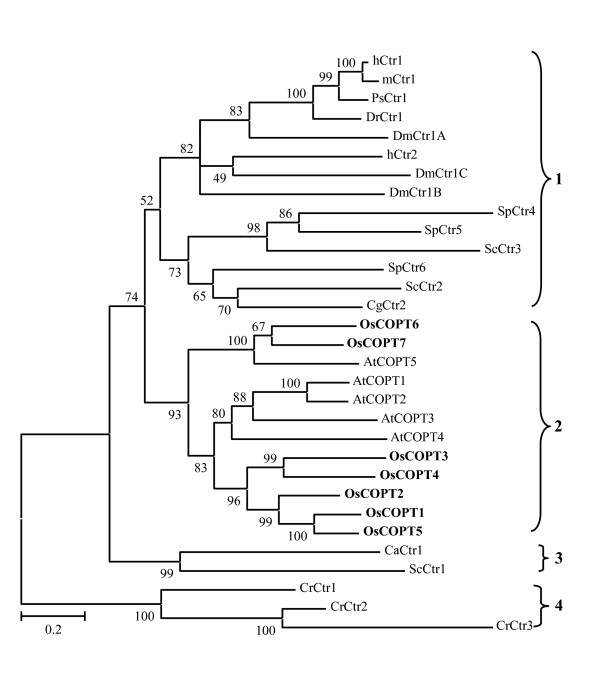

A phylogenetic analysis was performed to examine the evolutionary relationship of 31 COPT/Ctr proteins among rice and other species. This analysis classified these proteins into four groups (Figure 4). Group 1 includes Ctr proteins from humans (hCtr1 and hCtr2), mouse (Mus musculus; mCtr1), lizard (Podarcis sicula; PsCtr1), zebrafish (Danio rerio; DrCtr1), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster; DmCtr1A, DmCtr1B, DmCtr1C), baker's yeast (ScCtr2 and ScCtr3), fission yeast (S. pombe; SpCtr4, SpCtr5, and SpCtr6), and ascomycetes (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides; CgCtr2). Group 2 consists of seven rice COPTs (Oryza sativa; OsCOPT1 to OsCOPT7) and five Arabidopsis COPTs (Arabidopsis thaliana; AtCOPT1 to AtCOPT5). Group 3 includes two Ctrs from ascomycetes (C. albicans; CaCtr1) and baker's yeast (ScCtr1), respectively. Group 4 consists of three Ctrs from green algae (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii; CrCtr1, CrCtr2, and CrCtr3). This analysis suggests that rice COPTs are evolutionarily related to Arabidopsis COPTs rather than other COPT/Ctr proteins. Furthermore, rice COPT6 and COPT7 are more related to Arabidiopsis COPT5; rice COPT1 to COPT5 are more related to Arabidopsis COPT1 to COPT4 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationship of COPT/Ctr proteins from different species. The COPT/Ctr proteins were from human (hCtr1, accession number of GenBank or Protein database of National Center for Biotechnology Information http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov: NP_001850; hCtr2, NP_001851), mouse (mCtr1, NP_780299), lizard (PsCtr1, CAD13301), zebrafish (DrCtr1, NP_991280), fruit fly (DmCtr1A, NP_572336; DmCtr1B, NP_649790; DmCtr1C, NP_651837), baker's yeast (ScCtr1, NP_015449; ScCtr2, NP_012045; ScCtr3, NP_013515), fission yeast (SpCtr4, NP_587968; SpCtr5, NP_594269; SpCtr6, NP_595861), Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (CgCtr2, ABR23641), Arabidopsis (AtCOPT1, NP_200711; AtCOPT2, NP_190274; AtCOPT3, NP_200712; AtCOPT4, NP_850289; AtCOPT5, NP_197565), C. albicans (CaCtr1, CAB87806), and green algae (CrCtr1, XP_001693726; CrCtr2, XP_001702470; CrCtr3, XP_001702650). The numbers for interior branches indicate the bootstrap values (%) for 1000 replications. The scale at the bottom is in units of number of amino acid substitutions per site.

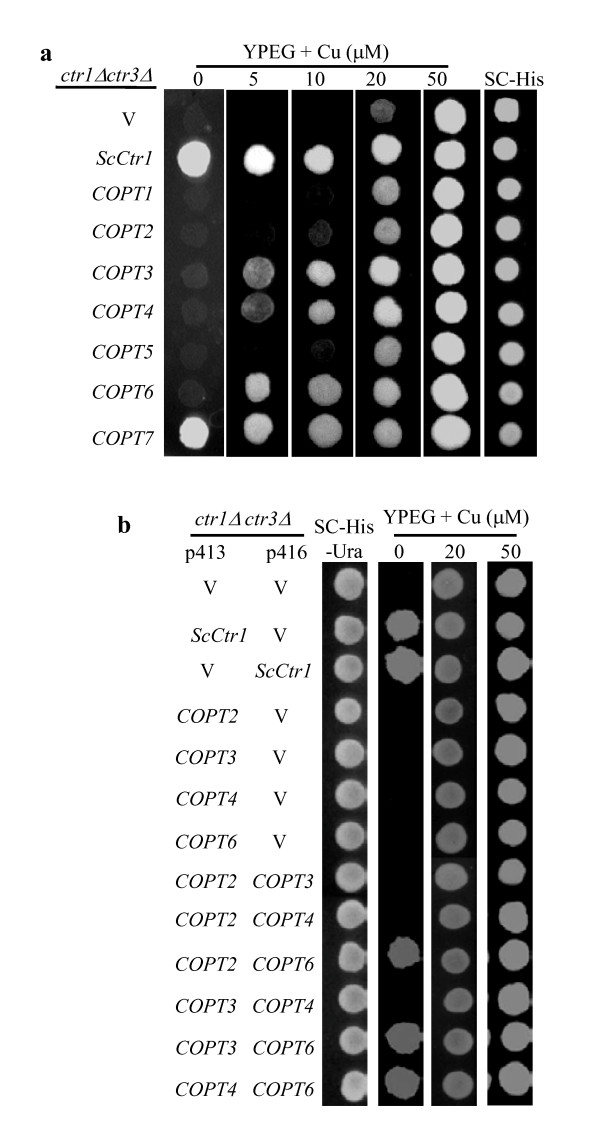

Rice COPTs function alone or cooperatively as high-affinity Cu transporters in yeast

A recent study has revealed that rice COPT1 and COPT5 alone or cooperatively cannot complement the phenotype of yeast S. cerevisiae mutant MPY17, which lacked the functions of Ctr1 and Ctr3 for Cu uptake; however, rice COPT1 and COPT5 in cooperation with another rice protein XA13 can mediate a low-affinity Cu transport in yeast MPY17 mutant and the three proteins also cooperatively mediate Cu transport in rice plants [29]. To investigate the potential roles of the other five rice COPT genes in Cu transport, these genes were expressed separately in MPY17 mutant under the control of the constitutive yeast glyceraldehide-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPD) gene promoter [39]. All the transformants were able to grow on SC-His, demonstrating the presence of the expression vector or target gene (Figure 5a). The lack of growth of MPY17 cells containing empty vector (negative control) was restored when transformed with yeast ScCtr1 (positive control) in the selective ethanol/glycerol (YPEG) medium without supplementation of Cu. Rice COPT7 but not rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 could replace the function of ScCtr1 in yeast cells. Expression of rice COPT7 alone could efficiently complement the phenotype of MPY17 mutant in the medium without supplementation of Cu as compared to the positive control (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Functional complementation of S. cerevisiae ctr1Δctr3Δmutant (MPY17) by expression of rice COPTs. Yeast ScCtr1 was used as positive control. Empty vector (V) was used as negative control. Transformants were grown in SC-His or SC-His-Ura medium to exponential phase and then spotted onto ethanol/glycerol (YPEG)-selective media supplemented with 5 to 50 μM CuSO4 or without supplementation of CuSO4 (0). (a) Expression of COPTs alone. (b) Coexpression of COPTs. The p413 and p416 are yeast expression vectors.

Rice COPT6 could efficiently complement MPY17 phenotype in the medium supplemented with 5 μM Cu compared to the growth of MPY17 cells transformed with COPT7 and the positive control, in the same medium (Figure 5a). Rice COPT3 and COPT4 could also complement MPY17 growth in the medium supplemented with 5 μM Cu, but with a relatively low efficiency. Like rice COPT1 and COPT5, rice COPT2 could not complement MPY17 growth in the medium supplemented with 5 μM Cu compared to the negative control. To determine whether expression of XA13 could enhance the ability of COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 to rescue the yeast mutant, we coexpressed these proteins with XA13. Coexpression of COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 with XA13 could not complement the phenotype of MPY17 (Additional file, Figure S1), which is consistent with our previous results that these COPT proteins can not interact with XA13 [29].

However, coexpression of COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 with COPT6 efficiently complemented the phenotype of MPY17 in the media without supplementation of Cu as compared to the positive control, while coexpression of COPT2-COPT3, COPT2-COPT4, or COPT3-COPT4 could not complement the phenotype of MPY17 (Figure 5b). To ascertain whether the cooperation of these two proteins in Cu uptake in yeast cells was associated with the physical contact of proteins, the interactions of these COPTs were analyzed using the split-ubiquitin system. All seven COPTs could form homodimers in yeast cells (Figure 3). Consistent with the complementation analyses, COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 could interact with COPT6, in addition to the interaction of COPT1 with COPT5 as reported previously (Figure 3) [29]. No other COPT pairs could form heterodimers in the yeast cells. These results suggest that COPT7 alone and COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 cooperating with COPT6, respectively, can mediate a highly efficient Cu transport into yeast cells. In addition, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 alone appear to mediate low-affinity Cu transport in yeast cells.

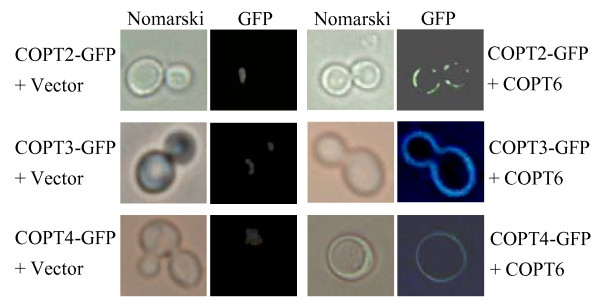

To ascertain whether the requirement of COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 with COPT6 to complement MPY17 phenotype was due to COPT6 affecting the localization of these proteins, we examined the localization of these proteins in the MPY17 cells by marking them with GFP. The COPT2-GFP, COPT3-GFP, or COPT4-GFP fusion protein was not or was not largely localized in the plasma membrane of the yeast cells when expressed alone (Figure 6). However, when coexpressed with COPT6, COPT2-GFP, COPT3-GFP, or COPT4-GFP was largely localized in the plasma membrane. These results suggest that COPT6 may function as a cofactor to help the efficient localization of COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 in the plasma membrane for mediating Cu transport.

Figure 6.

Localization of COPT2-GFP, COPT3-GFP and COPT4-GFP in yeast MPY17 cells in the presence and absence of COPT6. MPY17 cells were co-transformed with p413GPD-COPT2-GFP, p413GPD-COPT3-GFP, or p413GPD-COPT4-GFP and p416GPD (empty vector) or p416GPD-COPT6 and grown to log phase on SC-His-Ura. The GFP signal and Nomarski optical images were observed using a fluorescence microscopy.

Rice COPTs cannot transport Fe and Zn in yeast

Except for Cu uptake, COPT/Ctr proteins have been reported to be involved in transport other substances [49-51]. To ascertain whether rice COPTs had the capability of transporting other bivalent metal cations in organisms, these COPT genes were expressed in yeast S. cerevisiae mutants under the control of the GPD gene promoter. The fet3fet4DEY1453 mutant lacked the Fet3 and Fet4 proteins and was defective in both low- and high-affinity Fe uptake [40]. In the same selective BPDS media with or without supplement of Fe, yeast mutant cells transformed with one of the seven rice COPTs showed the same growth pattern as the yeast mutant cells transformed with empty vector (negative control); these cells did not grow in the medium without supplement of Fe (Additional file 1, Figure S2). However, the wild-type yeast strain DEY1457, which was transformed with the empty vector, grew well in the media in all the treatments. These results suggest that none of the rice COPTs alone can mediate Fe uptake in yeast.

The zrt1zrt2ZHY3 mutant lacked the Zrt1 and Zrt2 proteins for Zn uptake [41,42]. In the selective EDTA media without supplement of Zn, the mutant cells transformed with any one of the rice COPTs could not grow as the cells transformed with empty vector (negative control), whereas the wild-type DEY1457 transformed with the empty vector grew well (Additional file 1, Figure S2). These results suggest that rice COPTs alone cannot transport Zn in yeast either.

Since coexpression of COPT6 facilitated expression of COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 in the plasma membrane of yeast cells (Figure 6), we coexpressed each two of the four proteins in fet3fet4DEY1453 and zrt1zrt2ZHY3 yeast mutants. Coexpression of any two of the four proteins could not complement the phenotypes of the mutants (Additional file 1, Figure S3). These results further support the conclusion that rice COPTs cannot transport Fe and Zn in yeast.

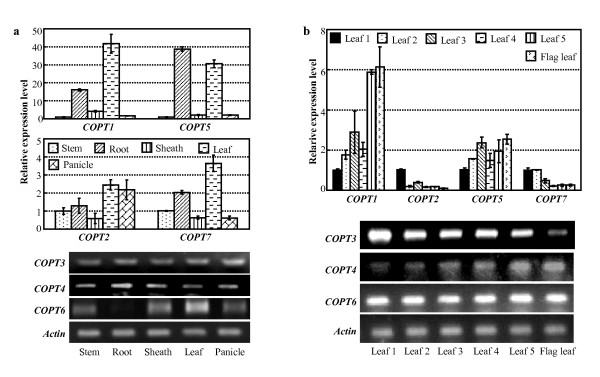

The expression of COPTs is influenced by multiple factors

To gain insight into the functions of rice COPTs, spatiotemporal and tissue-specific expression patterns of these genes were analyzed by qRT-PCR or RT-PCR (it is difficult to design PCR primers to analyze some COPT members by qRT-PCR). COPT1 and COPT5 showed similar tissue- and development-specific expression patterns. The two genes had a higher level of expression in root and leaf tissues compared to their expression levels in sheath, stem, and panicle (Figure 7a). COPT4 showed a higher expression level in root than in other tissues. COPT1, COPT4, and COPT5 had higher expression levels in young leaves than in old leaves, especially for COPT1 and COPT4 (Figure 7b). COPT2 and COPT3 had relatively higher expression levels in leaf and panicle than in other tissues and COPT7 had relatively higher expression levels in root and leaf than in other tissues; the three genes showed higher expression levels in old leaves compared with young leaves. COPT6 was not expressed in root and had a higher expression level in leaf than in other tissues. COPT6 showed a constitutive expression pattern in different-aged leaves.

Figure 7.

The tissue-specific and spatiotemporal expression patterns of rice COPT genes by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR. Bar represents mean (3 replicates) ± standard deviation. (a) Expression of COPTs in different rice tissues. (b) Expression of COPTs in different aged rice leaves in booting-stage plants, which produced six leaves in the main shoot. Leaf 1 was the oldest leaf and flag leaf was the youngest leaf in the plants.

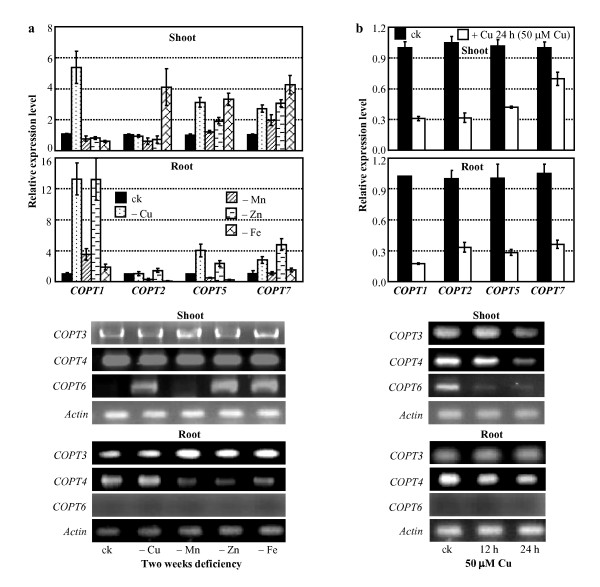

The expression of rice COPT1 and COPT5 was influenced by Cu; COPT1 and COPT5 were induced by Cu deficiency and suppressed by overdose of Cu in both shoot and root tissues [29]. The expression of other five rice COPTs, COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7, was also influenced by the change of Cu levels (Figure 8). COPT7 showed a similar response as COPT1 and COPT5 to Cu deficiency and overdose (50 μM) in both shoot and root compared to the control plants cultured in the medium containing 0.2 μM Cu. Although COPT6 showed constitutive expression in different aged leaves at adult stage (Figure 7b), it had a low level of expression in shoot tissue at seedling stage (Figure 8a). However, COPT6 was induced in Cu deficiency and suppressed in Cu overdose in shoot and no COPT6 expression was detected either with or without Cu deficiency in root (Figure 8). The expression of COPT2, COPT3, and COPT4 was suppressed in Cu overdose and was not obviously influenced in Cu deficiency in both shoot and root tissues.

Figure 8.

Expression of COPTs in rice was influenced by bivalent cations. Rice variety Zhonghua 11 at the four-leaf stage grown in hydroponic culture was used for qRT-PCR and RT-PCR analyses. Bar represents mean (3 replicates) ± standard deviation. ck, standard physiological Cu (0.2 mM), Mn (0.5 mM), Zn (0.5 mM), and Fe (0.1 mM). (a) Expression of COPTs was induced at 3 weeks after deficiency of Cu, Mn, Zn or Fe. -Cu, -Mn, -Zn, or -Fe, deficiency of Cu, Mn, Zn, or Fe. (b) Expression of COPTs was suppressed by overdose of Cu.

Interestingly, other bivalent cations also influenced expression of COPTs (Figure 8a). Mn deficiency induced COPT1 in root and COPT3 and COPT7 in shoot, and slightly suppressed COPT2 and COPT4 in root. Zn deficiency induced COPT1, COPT5, and COPT7 and slightly suppressed COPT4 in root and induced COPT5, COPT6, and COPT7 in shoot. Fe deficiency slightly induced COPT1 and suppressed COPT2 and COPT5 in root and induced COPT2, COPT5, COPT6, and COPT7 in shoot. No COPT6 expression was detected either with or without Mn, Zn, or Fe deficiency in root (Figure 8a).

Xoo strain PXO99 induced expression of COPT1 and COPT5, which encoding proteins interacted with XA13 protein to facilitate Xoo infection [29]. To ascertain whether the expression of other COPTs was also response to pathogen infection, rice plants were inoculated with different Xoo strains. Infection of Xoo strain PXO99 could not induce COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, or COPT7 (Additional file 1, Figure S4). Infection of Xoo strain PXO66 appeared slightly induced in COPT1 and COPT5, although the induction was statistically not significant (P > 0.05), but not in other COPTs (Additional file 1, Figure S5). These results suggest that COPT members may function differently in different tissues, different developmental stages, and different environments.

Discussion

The present results suggest that rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7, which function alone or cooperatively, can replace the roles of ScCtr1 and ScCtr3 for Cu uptake in S. cerevisiae. Previous studies have reported that a single plasma membrane-localized COPT/Ctr-type Cu transporter from human (hCtr1), mouse (mCtr1), Arabidopsis (AtCOPT1, 2, 3, and 5), lizard (PsCtr1), Drosophila (DmCtr1A, B, and C), or Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (CrCTR1 and CrCTR2) could complement the phenotype of S. cerevisiae ctr1Δctr3Δ mutant [13,16,17,23,24,28,52]. The fission yeast (S. pombe) SpCtr4 and SpCtr5 form a heteromeric plasma membrane complex to complement the S. cerevisiae ctr1Δctr3Δ mutant [19]; coexpression of this complex could also restore the phenotype of S. pombe ctr4Δctr5Δ mutant JSY22 [21,53]. Rice COPT1, COPT5, and the MtN3/saliva-type protein XA13, which cooperatively mediate Cu transport in rice, can also complement the phenotype of the S. cerevisiae ctr1Δctr3Δ mutant [29]. These results suggest that the S. cerevisiae ctr1Δctr3Δ mutant is a valuable model to study the roles of COPT/Ctr-type proteins from different species including rice in Cu transport. Thus, based on the effects of different rice COPTs on the growth of ctr1Δctr3Δ mutant cells on the selective media and the expression patterns of these COPT genes in response to the variation of Cu concentration in rice, we argue that COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7 may mediate Cu transport in rice alone or in cooperation with other COPTs.

COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 may cooperate with COPT6 for Cu transport in different rice tissues except for root. This hypothesis is supported by the following evidence. First, the complementation of the phenotype of S. cerevisiae ctr1Δctr3Δ mutant by coexpression of COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 with COPT6 was consistent with the capability of the physical interaction of COPT2, COPT3, or COPT4 with COPT6 (Figures 3 and 5b). Second, COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, and COPT6 were all expressed in stem, sheath, leaf, and panicle tissues (Figure 7). The similar and tissue-specific expression patterns of COPT1 and COPT5 (Figure 7) are consistent with their cooperative role in Cu transport in shoot and root reported previously [29]. However, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 alone appeared to mediate a low-affinity Cu transport in yeast cells, suggesting that they may be also involved in a low-affinity Cu transport in different rice tissues or rice Cu deficiency alone, although further in planta study is required to examine this hypothesis. This hypothesis is supported by the evidence that COPT3 and COPT4 had a relatively high level of expression in root, but no expression of COPT6 was detected in root; furthermore, the expression of COPT2, COPT3, and COPT4 but not COPT6 in leaves was developmentally regulated (Figure 7). In addition, the expression of COPT6 but not COPT2, COPT3, and COPT4 was strongly induced by Cu deficiency in rice shoot (Figure 8). The present results also suggest that COPT7 may be capable of mediating Cu transport alone in rice. According to its expression pattern, COPT7 may function in different tissues and also in Cu deficiency.

Except for Cu uptake, human hCtr1 could transport silver (Ag) [51]. This capability of the hCtr1 occurs because Ag(I) is isoelectronic to Cu(I) and thus Ag competes for Cu as the substrate of the hCtr1 [22]. Furthermore, ScCtr1, mCtr1, and hCtr1 could also transport the anticancer drug cisplatin [49,50]. None of the rice COPTs could restore the Fe- or Zn-uptake functions of the yeast mutants (Additional file 1, Figures S2, S3). Overexpressing COPT1 or COPT5 or suppressing COPT1 or COPT5 in rice had no influence on Fe, Mn, and Zn contents in rice shoot [29]. These results suggest that rice COPTs may function specifically for Cu transport among bivalent ions like the other COPT/Ctr proteins [32]. That the COPT/Ctr proteins could transport Cu but not Fe, Mn, and Zn may be related to their protein features. The TM domains of COPT/Ctr may form a symmetrical homotrimer or heterotrimer channel architecture with a 9-Å diameter that is suitable only for Cu(I) transport but not other bivalent ions, such as Mn, Zn, or Fe [33].

However, all the rice COPTs were transcriptionally activated or suppressed by Fe, Mn, or Zn deficiency (Figure 8a). A balance of the concentrations of Cu with other bivalent ions appears to be associated with their uptake. The yeast S. cerevisiae Ctr1 mutants and deletion strains have deficiency in Fe uptake [12]. The high-affinity Fe uptake is influenced by Cu concentration in ascomycetes C. albicans; deletion of CaCTR1 for Cu uptake results in defective Fe uptake [26]. Excess metals (Fe, Mn, Zn, or cadmium) significantly influenced Cu uptake mediated by human hCtr1 [22]. A yeast S. pombe ctr6 mutant displays a strong reduction of Zn superoxide dismutase activity [20]. Thus, further study is required to determine whether other bivalent ion levels influence Cu uptake in rice.

Xoo causes bacterial blight, which is one of the most devastating diseases restricting rice production worldwide. Rice COPT1, COPT5, and XA13 cooperate to promote removal of Cu from rice xylem vessels, where Xoo multiplies and spreads to cause disease [29]. COPT1, COPT5, and Xa13 can facilitate the infection of Xoo strain PXO99 because this bacterium can transcriptionally activate them [29]. The present results suggest that Xoo-induced expression of COPT1 and COPT5 is race specific. Although PXO99 can induce COPT1 and COPT5 [29], the expression of the two genes was not markedly influenced by Xoo strain PXO61 in the infection sites (Additional file 1, Figure S5). Neither PXO61 nor PXO99 influenced the expression of rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7 in the infection sites, suggesting that these COPT genes are not directly involved in the interactions between rice and at least the two Xoo strains.

Conclusion

Like rice COPT1 and COPT5 [29], rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, COPT6, and COPT7 also appear to be plasma membrane proteins for they can replace the roles of S. cerevisiae plasma membrane-localized ScCtr1 and ScCtr3 for Cu uptake. However, different from COPT1 and COPT5, the other five COPTs may not be directly associated with the rice-Xoo interaction. The present results provide tissue and interaction targets of different COPTs for further study of their roles in Cu transport and associated physiological activities in rice.

Authors' contributions

MY performed functional complementation and gene expression analyses and drafted the manuscript. XL and JX provided biochemical and molecular analysis supports. SW contributed to data interpretation and to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental tables and figures. Table S1: PCR primers used for quantitative RT-PCR or RT-PCR assays. Table S2: PCR primers used for yeast complementation experiments. Table S3: PCR primers used for protein-protein interaction assays. Table S4: PCR primers used for protein topology analyses. Figure S1: Coexpression of rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 with Xa13 could not complement S. cerevisiae ctr1Dctr3D mutant (MPY17). Complementation is indicated by growth on the media with 0, 20, or 50 mM copper (Cu). The p413 and p416 are yeast expression vectors. Yeast ScCtr1 and empty vector (V) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Transformants were grown in SC-His-Ura medium to exponential phase and spotted onto SC-His-Ura and ethanol/glycerol (YPEG) plates. Figure S2: Analyses of the functions of rice COPTs in Fe-uptake and Zn-uptake mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The yeast DEY1457 strain was wild type. Yeast cells diluted in gradient were plated on selective media (OD values: 1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 from left to right). (a) Functional analysis rice COPTs in yeast fet3fet4DEY1453 mutant strain, which lacked the Fet3 and Fet4 for Fe uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective bathophenanthroinedisulfonic acid disodium (BPDS) media with or without supplement of Fe (FeSO4). (b) Functional analysis of rice COPTs in yeast zrt1zrt2ZHY3 mutant strain, which lacked the Zrt1 and Zrt2 for Zn uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective EDTA media with or without supplement of Zn (ZnSO4). Figure S3: Further analyses of the functions of rice COPTs in Fe-uptake and Zn-uptake mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The yeast DEY1457 strain was wild type. Yeast cells diluted in gradient were plated on selective media. Empty vector (V) was used as negative control. The p413 and p416 are yeast expression vectors. (a) Functional analysis rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, and COPT6 in yeast fet3fet4DEY1453 mutant strain, which lacked the Fet3 and Fet4 for Fe uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective bathophenanthroinedisulfonic acid disodium (BPDS) media with or without supplement of Fe (FeSO4). (b) Functional analysis of rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, and COPT6 in yeast zrt1zrt2ZHY3 mutant strain, which lacked the Zrt1 and Zrt2 for Zn uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective EDTA media with or without supplement of Zn (ZnSO4). Figure S4: Infection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain PXO99 did not influence the expression of COPTs in susceptible rice variety IR24 analyzed by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR. Bar represents mean (3 replicates) ± standard deviation. Plants were inoculated with PXO99 at booting (panicle development) stage. ck, before infection. Figure S5: The expression of COPTs after infection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain PXO61 in susceptible rice variety IR24 analyzed by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR. Bar represents mean (3 replicates) ± standard deviation. Plants were inoculated with PXO61 at booting (panicle development) stage. ck, before infection.

Contributor Information

Meng Yuan, Email: djyuanm@webmail.hzau.edu.cn.

Xianghua Li, Email: xhli@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Jinghua Xiao, Email: xiaojh@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Shiping Wang, Email: swang@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Dennis J. Thiele of Duke University Medical Center for providing yeast copper-uptake mutant and plasmids and Dr. David Eide of University of Wisconsin-Madison and Dr. Hongsheng Zhang of Nanjing Agricultural University for providing yeast iron-uptake mutant and zinc-uptake mutant. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30930063, 30921091).

References

- DiDonato M, Sarkar B. Copper transport and its alterations in Menkes and Wilson diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1360:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(96)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohaska JR. Long-term functional consequences of malnutrition during brain development: copper. Nutrition. 2000;16:502–504. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penarrubia L, Andres-Colas N, Moreno J, Puig S. Regulation of copper transport in Arabidopsis thaliana: a biochemical oscillator? J Biol Inorganic Chem. 2010;15:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhead JL, Reynolds KA, Abdel-Ghany SE, Cohu CM, Pilon M. Copper homeostasis. New Phytol. 2009;182:799–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S. Molecular mechanisms of plant metal tolerance and homeostasis. Planta. 2001;212:475–486. doi: 10.1007/s004250000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelblau E, Amasino RM. Delivering copper within plant cells. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S, Thiele DJ. Molecular mechanisms of copper uptake and distribution. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LE, Pittman JK, Hall JL. Emerging mechanisms for heavy metal transport in plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:104–126. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LE, Mills RF. P1B-ATPases-an ancient family of transition metal pumps with diverse function in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Chu HH, Didonato RJ, Roberts LA, Eisley RB, Lahner B, Salt DE, Walker EL. Mutations in Arabidopsis yellow stripe-like 1 and yellow stripe-like 3 reveal their roles in metal ion homeostasis ans loading of metal ions in seeds. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:1446–1458. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S, Andres-Colas N, Garcia-Molina A, Penarrubia L. Copper and iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis: response to metal deficiencies, interactions and biotechnological applications. Plant Cell Environ. 2007;30:271–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancis A, Yuan DS, Haile D, Askwith C, Eide D, Moehle C, Kaplan J, Klausner RD. Molecular characterization of a copper transport protein in S. cerevisiae: an unexpected role for copper in iron transport. Cell. 1994;76:393–402. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90345-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfenkel K, Kushnir S, Babiychuk E, Inze D, Vanmontagu M. Molecular characterization of a putative Arabidopsis-thaliana copper transporter and its yeast homolog. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28479–28486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pena MMO, Koch KA, Thiele DJ. Dynamic regulation of copper uptake and detoxification genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2514–2523. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees EM, Lee J, Thiele DJ. Mobilization of intracellular copper stores by the Ctr2 vacuolar copper transporter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54221–54229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancenon V, Puig S, Mateu-Andres I, Dorcey E, Thiele DJ, Penarrubia L. The Arabidopsis copper transporter COPT1 functions in root elongation and pollen development. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15348–15355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Gitschier J. hCTR1: a human gene for copper uptake identified by complementation in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7481–7486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berghe PV, Folmer DE, Malingre HEM, Van Beurden E, Klomp AEM, De Sluis BV, Merkx M, Berger R, Klomp LWJ. Human copper transporter 2 is localized in late endosomes and lysosomes and facilitates cellular copper uptake. Biochem J. 2007;407:49–59. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Thiele DJ. Identification of a novel high affinity copper transport complex in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20529–20535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellemare DR, Shaner L, Morano KA, Beaudoin J, Langlois J, Labbe S. Ctr6, a vacuolar membrane copper transporter in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46676–46686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin J, Laliberte J, Labbe S. Functional dissection of Ctr4 and Ctr5 amino-terminal regions reveals motifs with redundant roles in copper transport. Microbiology-Sgm. 2006;152:209–222. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Pena MMO, Nose Y, Thiele DJ. Biochemical characterization of the human copper transporter Ctr1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4380–4387. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggio M, Lee J, Scudiero R, Parisi E, Thiele DJ, Filosa S. High affinity copper transport protein in the lizard Podarcis sicula: molecular cloning, functional characterization and expression in somatic tissues, follicular oocytes and eggs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1576:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00337-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Cadigan KM, Thiele DJ. A copper-regulated transporter required for copper acquisition, pigmentation, and specific stages of development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48210–48218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie NC, Brito M, Reyes AE, Allende ML. Cloning, expression pattern and essentiality of the high-affinity copper transporter 1 (ctr1) gene in zebrafish. Gene. 2004;328:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvin ME, Mason RP, Cashmore AM. The CaCTR1 gene is required for high-affinity iron uptake and is transcriptionally controlled by a copper-sensing transactivator encoded by CaMAC1. Microbiology. 2004;150:2197–2208. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhoom S, Kupiec M, Zhao X, Xu JR, Sharon A. Functional characterization of CgCTR2, a putative vacuole copper transporter that is involved in germination and pathogenicity in Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1098–1108. doi: 10.1128/EC.00109-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MD, Kropat J, Hamel PP, Merchant SS. Two Chlamydomonas CTR copper transporters with a novel cys-met motif are localized to the plasma membrane and function in copper assimilation. Plant Cell. 2009;21:928–943. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M, Chu Z, Li X, Xu C, Wang S. The bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae overcomes rice defenses by regulating host copper redistribution. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3164–3176. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korripally P, Tiwari A, Haritha A, Kiranmayi P, Bhanoori M. Characterization of Ctr family genes and the elucidation of their role in the life cycle of Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Kikuchi S, Sakamoto Y, Yano A. Identification and characterization of CcCTR1, a copper uptake transporter-like gene, in Coprinopsis cinerea. Microbiol Res. 2010;165:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BE, Nevitt T, Thiele DJ. Mechanisms for copper acquisition, distribution and regulation. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:176–185. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nose Y, Rees EM, Thiele DJ. Structure of the Ctr1 copper trans'PORE'ter reveals novel architecture. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:604–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aller SG, Unger VM. Projection structure of the human copper transporter CTR1 at 6-A resolution reveals a compact trimer with a novel channel-like architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3627–3632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509929103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petris MJ. The SLC31 (Ctr) copper transporter family. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:752–755. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z, Loughlin F, George GN, Howlett GJ, Wedd AG. C-terminal domain of the membrane copper transporter Ctr1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae binds four Cu(I) ions as a cuprous-thiolate polynuclear cluster: sub-femtomolar Cu(I) affinity of three proteins involved in copper trafficking. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3081–3090. doi: 10.1021/ja0390350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berghe PV, Klomp LW. Posttranslational regulation of copper transporters. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Cao Y, Yang Z, Xu C, Li X, Wang S, Zhang Q. Xa26, a gene conferring resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice, encoding a LRR receptor kinase-like protein. Plant J. 2004;37:517–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 1995;156:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eide D, Broderius M, Fett J, Guerinot ML. A novel iron regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5624–5628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Eide D. The yeast ZRT1 gene encodes the zinc transporter protein of a high-affinity uptake system induced by zinc limitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2454–2458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Eide D. The ZRT2 gene encodes the low affinity zinc transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23203–23210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig S, Lee J, Lau M, Thiele DJ. Biochemical and genetic analysis of yeast and human high affinity copper transporters suggest a conserved mechanism for copper uptake. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26021–26030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Feo CJ, Aller SG, Unger VM. A structural perspective on copper uptake in eukaryotes. Biometals. 2007;20:705–716. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z, Wedd AG. A C-terminal domain of the membrane copper pump Ctr1 exchanges copper (I) with the copper chaperone Atx1. Chem Commun (Camb) 2002;21:588–589. doi: 10.1039/b111180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinders A, Schulze W, Thaminy S, Stagljar I, Frommer WB, Ward JM. Intra- and intermolecular interaction is sucrose transporters at the plasma membrane detected by the split-ubiquitin system and functional assays. Structure. 2002;10:763–772. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S, Lee J, Thiele DJ, Herskowitz I. Uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin mediated by the copper transporter Ctr1 in yeast and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14298–14302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162491399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta GL, Gatti L, Tinelli S, Corna E, Colangelo D, Zunino F, Perego P. Cellular pharmacology of cisplatin in relation to the expression of human copper transporter CTR1 in different pairs of cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinao J, Cheung L, Hoque R, Plouffe LJ. Ctr1 transports silver into mammalian cells. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2010;24:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Prohaska JR, Dagenais SL, Glover TW, Thiele DJ. Isolation of a murine copper transporter gene, tissue specific expression and functional complementation of a yeast copper transport mutant. Gene. 2000;254:87–96. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannoni R, Beaudoin J, Mercier A, Labbe S. Copper-dependent trafficking of the Ctr4-Ctr5 copper transporting complex. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental tables and figures. Table S1: PCR primers used for quantitative RT-PCR or RT-PCR assays. Table S2: PCR primers used for yeast complementation experiments. Table S3: PCR primers used for protein-protein interaction assays. Table S4: PCR primers used for protein topology analyses. Figure S1: Coexpression of rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, or COPT6 with Xa13 could not complement S. cerevisiae ctr1Dctr3D mutant (MPY17). Complementation is indicated by growth on the media with 0, 20, or 50 mM copper (Cu). The p413 and p416 are yeast expression vectors. Yeast ScCtr1 and empty vector (V) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Transformants were grown in SC-His-Ura medium to exponential phase and spotted onto SC-His-Ura and ethanol/glycerol (YPEG) plates. Figure S2: Analyses of the functions of rice COPTs in Fe-uptake and Zn-uptake mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The yeast DEY1457 strain was wild type. Yeast cells diluted in gradient were plated on selective media (OD values: 1, 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001 from left to right). (a) Functional analysis rice COPTs in yeast fet3fet4DEY1453 mutant strain, which lacked the Fet3 and Fet4 for Fe uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective bathophenanthroinedisulfonic acid disodium (BPDS) media with or without supplement of Fe (FeSO4). (b) Functional analysis of rice COPTs in yeast zrt1zrt2ZHY3 mutant strain, which lacked the Zrt1 and Zrt2 for Zn uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective EDTA media with or without supplement of Zn (ZnSO4). Figure S3: Further analyses of the functions of rice COPTs in Fe-uptake and Zn-uptake mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The yeast DEY1457 strain was wild type. Yeast cells diluted in gradient were plated on selective media. Empty vector (V) was used as negative control. The p413 and p416 are yeast expression vectors. (a) Functional analysis rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, and COPT6 in yeast fet3fet4DEY1453 mutant strain, which lacked the Fet3 and Fet4 for Fe uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective bathophenanthroinedisulfonic acid disodium (BPDS) media with or without supplement of Fe (FeSO4). (b) Functional analysis of rice COPT2, COPT3, COPT4, and COPT6 in yeast zrt1zrt2ZHY3 mutant strain, which lacked the Zrt1 and Zrt2 for Zn uptake. The transformants were spotted onto selective EDTA media with or without supplement of Zn (ZnSO4). Figure S4: Infection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain PXO99 did not influence the expression of COPTs in susceptible rice variety IR24 analyzed by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR. Bar represents mean (3 replicates) ± standard deviation. Plants were inoculated with PXO99 at booting (panicle development) stage. ck, before infection. Figure S5: The expression of COPTs after infection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strain PXO61 in susceptible rice variety IR24 analyzed by qRT-PCR and RT-PCR. Bar represents mean (3 replicates) ± standard deviation. Plants were inoculated with PXO61 at booting (panicle development) stage. ck, before infection.