Abstract

Enantioselective intramolecular oxidative amidation of alkenes has been achieved using a (pyrox)Pd(II)(TFA)2 catalyst (pyrox = pyridine-oxazoline, TFA = trifluoroacetate) and O2 as the sole stoichiometric oxidant. The reactions proceed at room temperature in good-to-excellent yield (58-98%) and with high enantioselectivity (ee = 92-98%). Catalyst-controlled stereoselective cyclization reactions are demonstrated for a number of chiral substrates. DFT calculations suggest that the electronic asymmetry of the pyrox ligand synergizes with steric asymmetry to control the stereochemical outcome of the key amidopalladation step.

Wacker-type oxidative cyclization reactions provide efficient access to oxygen and nitrogen heterocycles and have been the subject of longstanding interest.1 Despite extensive efforts, development of enantioselective methods remains a key challenge.1i,2-4 Here, we describe a simple catalyst system consisting of Pd(TFA)2 (TFA = trifluoroacetate) and a pyridine-oxazoline (pyrox) ligand that enables high yields and enantioselectivities in the intramolecular aerobic oxidative amidation of unactivated alkenes bearing tethered sulfonamide nucleophiles. The aliphatic tethers do not require conformational biasing groups (e.g., gem-disubstitution or fused cyclic substituents) to achieve efficient cyclization. DFT computational studies provide a preliminary model for the origin of catalyst stereocontrol in these reactions and provide insights into the electronic and steric asymmetry of pyrox ligands.

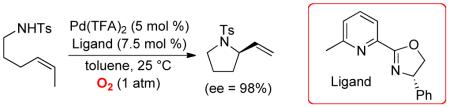

In 2002, we reported Pd(OAc)2/pyridine-catalyzed aerobic oxidative cyclization of alkenyl sulfonamides such as 1 (Scheme 1A),5a,6 and mechanistic studies of this catalyst system have shown that this reaction proceeds via turnover-limiting cis-amidopalladation of the alkene.5b,c This PdII/pyridine catalyst system has been the starting point for development of other enantioselective aerobic oxidative cyclization reactions;3 however, previous work from our lab suggested that bidentate ligands inhibit the oxidative cyclization of 1 (Scheme 1B).

Scheme 1.

Pd(OAc)2/Pyridine-Catalyzed Intramolecular Aerobic Oxidative Amidation of an Alkene and Ligand Effects.

Reaction conditions: 5 mol % PdX2, 7.5 mol % ligand (10 mol % Py), O2 (1 atm), molecular sieves 3 Å, toluene (0.1 M), 50 °C, 12 h.

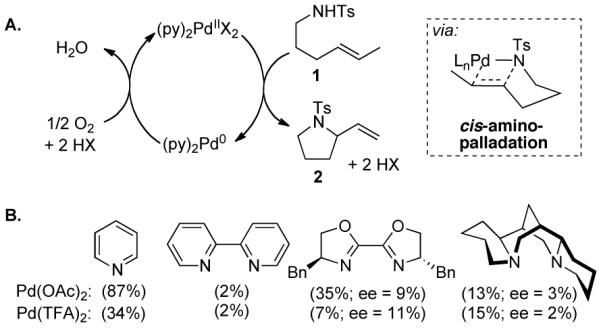

Recently, pyrox and quinoline-oxazoline (quinox) ligands have emerged as an effective class of ligands for enantioselective PdII-catalyzed reactions. Early applications of these ligands were reported by Widenhoefer in PdII-catalyzed hydrosilylation/cyclization of 1,6-dienes,7 and, more recently, they have been used in enantioselective aerobic oxidative Heck reactions,8 C–O bond-forming reactions with ortho-vinyl phenols,9 oxidative cyclization reactions with ortho-allyl anilines,3d,f and other applications.10 In this context, we tested the aerobic oxidative cyclization of alkenyl sulfonamide 1 in the presence of PdII salts and the C1-symmetric Bn-quinox ligand. Use of this ligand in combination with Pd(TFA)2 and 3Å molecular sieves (M.S.) in toluene afforded pyrrolidine 2 in 66% enantiomeric excess and 37% yield, substantially better than our earlier results (Scheme 2; cf. Scheme 1B). A similar yield, but lower enantioselectivity, was observed with Pd(OAc)2 as the Pd source.

Scheme 2.

Enantioselective Oxidative Amidation Employing Pyridine Oxazoline Ligands.

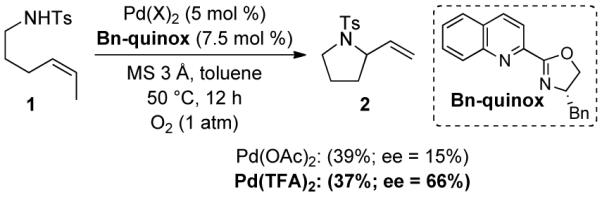

The modular nature and ease of synthesis of pyridine-oxazolines enabled a straightforward evaluation of a focused library of ligands. Systematic variation of the pyridine and oxazoline groups revealed that a phenyl glycinol derived oxazoline and a 6-methyl functionalized pyridine provided the highest levels of enantioselectivity (Scheme 3). These subunits were incorporated into ligand 3, and use of this ligand in the oxidative cyclization reaction resulted in 91% enantiomeric excess and 60% yield. Decreasing the ligand loading from 7.5% to 5.5% led to slightly lower enantioselectivity. In the absence of 3Å M.S., both the yield and enantioselectivity were reduced. Carrying out the reaction at room temperature resulted in the formation of pyrrolidine 2 in 98% ee and 68% yield. The cis alkene was important to the reaction outcome: use of trans-1 as the substrate under the optimized conditions formed 2 in 51% yield and 50% e.e. Both alkene isomers generated the (R) enantiomer of the pyrrolidine as the major product with (S)-3 as the ligand.11

Scheme 3.

Ligand Substituent Effects and Reaction Optimization.a

a Conditions: 1 (0.075 mmol), 1 atm O2, MS 3 Å (20 mg), toluene (0.75 mL), 12 h. Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy, internal standard = 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene. Enantiomeric excess deteremined by chiral HPLC (see Supporting Information for details). b 5.5 mol % ligand. c Without MS 3 Å. d 25 °C, 24 h. Isolated yield (0.5 mmol scale).

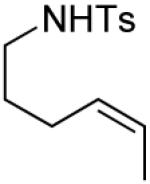

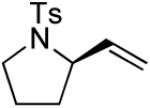

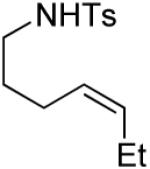

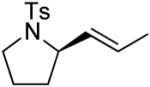

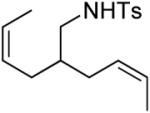

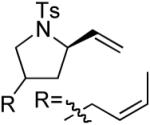

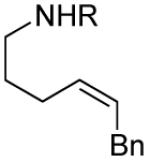

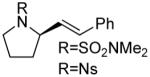

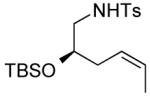

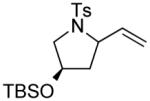

A number of other cis-alkenes underwent efficient cyclization to afford pyrrolidines with high levels of enantioselectivity (Table 1).12 Cyclization of ethyl and benzyl substituted alkenes generated products bearing an internal double bond in 97 and 93% ee, respectively (entry 2 and 3), and a gem-dimethyl substituted substrate cyclized in 92% ee (entry 4). A symmetrical diene cyclized to provide the desymmetrized product in 93% ee, albeit with moderate diastereoselectivity (entry 5). A sulfamide nitrogen nucleophile was also highly effective, furnishing the corresponding pyrrolidine in 92% ee and 95% yield (entry 6). Use of the more electron-withdrawing nosyl (Ns) N-substituent resulted in reduced yield and stereoselectivity (entry 7).

Table 1.

| entry | substrate | product | ligand | yield %c | ee %d or drb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

(S)-3 | 68 | 98 |

| 2 |

|

|

(S)-3 | 62 | 97 |

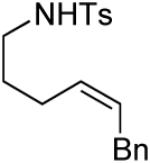

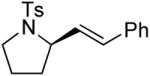

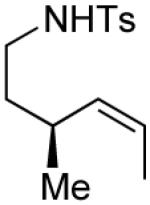

| 3 |

|

|

(S)-3 | 98 | 93 |

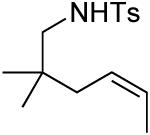

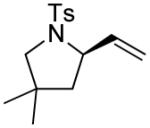

| 4 |

|

|

(S)-3 | 58 | 92 |

| 5 |

|

|

(S)-3 | 86 | 93 (95)f (d.r. = 1.4:1) |

| 6 |

|

|

(S)-3 | 95 | 92 |

| 7 | (S)-3 | 52 | 76 | ||

| 8 |

|

|

4 | --g | 1:7 |

| 9 | (R)-3 | 88 | <1:20 | ||

| 10 | (S)-3 | 23 (64)h | 7:1 | ||

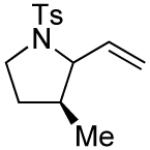

| 11 |

|

|

4 | --g | 1.5:1 |

| 12 | (R)-3 | 87 | 1:17 | ||

| 13 | (S)-3 | 90 | >20:1 | ||

| 14 |

|

|

4 | --g | 1.4:1 |

| 15 | (R)-3 | 97 | >20:1 | ||

| 16 | (S)-3 | 92 | <1:20 | ||

| 17 |

|

|

4 | --g | >20:1 |

| 18 | (R)-3 | 92 | >20:1 | ||

| 19 | (R)-3 | 77 | >20:1 |

Conditions: substrate (0.3 mmol), Pd(TFA)2 (15 μmol), ligand (22.5 μmol), MS 3 Å (80 mg), toluene (3 mL), 25 °C, 24 h.

Entries 8-19: 36 h.

Isolated yield.

Enantiomeric excess determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Diastereomeric ratio (anti:syn) determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture.

Enantiomeric excess of the minor diastereomer.

Substantial alkene isomerization was observed in these reactions, and the reaction yields were not optimized.

The number in parentheses refers to a mixture of olefin isomers.

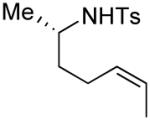

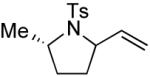

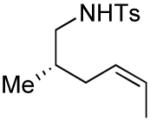

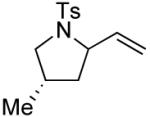

Several enantiomerically pure chiral substrates were investigated to probe the ability of the catalyst to control the stereochemical outcome of the reaction (Table 1, entries 8-19). The intrinsic substrate-controlled diastereoselectivities of these reactions were evaluated by performing the oxidative cyclization reactions with the achiral pyrox ligand 4, and the reactions were then repeated with a Pd catalyst bearing the (R)- or (S)-antipode of ligand 3. The sulfonamide substrate with an α-methyl substituent exhibited a diastereoselectivity of 1:7 favoring the cis-2,5-disubstituted pyrrolidine when the reaction was carried out with the achiral pyridine-oxazoline ligand 4 (entry 8). The same cis diastereomer was formed exclusively when (R)-3 was used as the ligand (entry 9), whereas the trans diastereomer was favored (d.r. = 7:1) when (S)-3 was used (entry 10). Although substantial alkene isomerization reduced the yield of the desired product in the latter reaction, these results highlight the ability of the ligand to overcome the substrate-controlled selectivity pattern. Investigation of two substrates with substituents in the β position further highlights the ability to achieve catalyst-controlled stereoselectivity (entries 11–16). When these substrates were tested independently with the two enantiomers of ligand 3, either diastereomer of the pyrrolidine products could be obtained in very good yield. A substrate with a methyl group adjacent to the alkene was not subject to catalyst control (entries 17–19); the same product diastereomer was obtained in good yield with either enantiomer of the ligand.

Despite the growing success of pyrox and quinox ligands in PdII-catalyzed reactions, comparatively little fundamental insight has been provided into the origins of enantioselectivity with these ligands. A full mechanistic study of these reactions is the focus of ongoing work, but preliminary DFT computational studies have provided some valuable insights. In our initial work, we have focused on an oxidative amidation pathway that proceeds via cis-amidopalladation of the alkene, analogous to that established with the Pd(OAc)2/pyridine catalyst (Scheme 1). The results reveal that the subtle electronic asymmetry of the two pyrox nitrogen ligands plays an important role in the stereochemical course of the reaction.

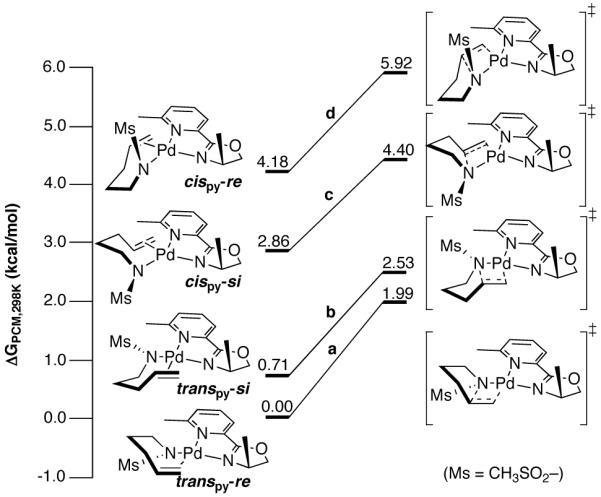

Four substrate-binding conformations were optimized for a putative PdII-(amidate-alkene) intermediate, in which the alkene is cis or trans with respect to the pyridine (cispy and transpy) and binds to Pd with re or si facial selectivity (re vs. si) (Scheme 4). The calculated free energies of the four ground-state structures reveals a preference for the sulfonamidate to coordinate cis to pyridine and with the Ms group anti to the oxazoline methyl group. This conformational preference is retained in the transition-state structures. The preference for the cispy orientation arises from the electronic asymmetry of the pyrox ligand, which is evident from analogous calculations with an unsubstituted pyrox ligand lacking significant steric effects: the cispy orientation is more stable than transpy by 1.76 kcal/mol.13 The observed electronic asymmetry is a result of the more basic oxazolinyl fragment exerting a stronger trans influence, thereby directing substrate orientation.13

Scheme 4.

Calculated Ground- and Transition-State Energies Associated with the cis-Amidopalladation of an Alkene at a Pyridine-Oxazoline-Ligated PdII-Center.a

a The cationic charge on all structures is omitted for clarity. Final structures were optimized with the following method (Gaussian 03): B3LYP; Stuttgart RSC 1997 ECP/triple-ζ basis for Pd; 6-311+G (d,p) basis on all other atoms; polarizable contiuum solvation model (toluene); see Supporting Information for computational details.

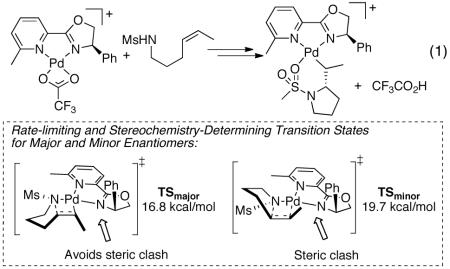

This analysis was expanded to a more experimentally relevant system by calculating the free energy profile for the reaction of the [(pyrox)Pd(TFA)]+ species and (Z)-4-hexenylmesylamide, illustrated in eq 1.13 The calculated relative free energies of the diastereomeric transition states, TSmajor and TSminor (ΔΔG‡cald = 2.9 kcal/mol), match the experimental result remarkably well (at 98% ee, the ΔΔG‡ = 2.7 kcal/mol). Analysis of the transition state structures TSmajor/minor reveal the vinylic methyl group in TSminor is in close proximity to the oxazolinyl phenyl group, whereas the vinylic methyl group in TSmajor is oriented downward, away from the phenyl group. This analysis highlights the synergy between the electronic asymmetry of the pyrox framework, which orients the substrate at the PdII center, and the steric effects of the oxazoline substituent, which differentiates the two enantiotopic faces of the alkene in the insertion step. These insights resemble principles elaborated by Trend and Stoltz on the electronic and steric influence of (−)- sparteine as a C1-symmetric ligand in the Pd-catalyzed oxidative kinetic resolution of secondary alcohols.14

|

In summary, we have developed highly enantioselective Wacker-type oxidative cyclizations of alkenes with sulfonamides linked via conformationally unconstrained aliphatic tethers. The Pd(pyrox)(TFA)2 catalyst for these reactions is very efficient, operating at room temperature, and highly selective. Preliminary computation insights into the origin of the enatioselectivity highlight the importance of electronic asymmetry in the pyrox ligand family, and they provide an important foundation for the rational design of new ligands for enantioselective transformations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. David M. Michaelis and Prof. Tehshik P. Yoon (UW–Madison) for generous donation of some of the ligands screened in this study and for helpful discussions. We thank the NIH (R01 GM67163) and Abbott Laboratories (graduate fellowship for R.I.M.) for financial support. Computational resources were supported by the NSF (TG-CHE-070040).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, characterization for all new compounds, and chiral HPLC traces, and computational data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).For reviews, see: Hegedus LS. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Semmelhack MF, editor. Vol. 4. Pergamon Press, Inc.; Elmsford: 1991. pp. 551–569. Hosokawa T, Murahashi S-I. In: Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis. Negishi E, de Meijere A, editors. Vol. 2. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; New York: 2002. pp. 2169–2192. Hosokawa T. In: Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis. Negishi E, de Meijere A, editors. Vol. 2. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; New York: 2002. pp. 2211–2225. Zeni G, Larock RC. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2285–2309. doi: 10.1021/cr020085h. Stahl SS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3400–3420. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630. Beccalli EM, Broggini G, Martinelli M, Sottocornola S. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:5318–5365. doi: 10.1021/cr068006f. Minatti A, Muniz K. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1142–1152. doi: 10.1039/b607474j. Kotov V, Scarborough CC, Stahl SS. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:1910–1923. doi: 10.1021/ic061997v. McDonald RI, Liu G, Stahl SS. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:2981–3019. doi: 10.1021/cr100371y.

- (2).See the following leading references: Hosokawa T, Uno T, Inui S, Murahashi S-I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:2318–2323. Uozumi Y, Kato K, Hayashi T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5063–5064. Uozumi Y, Kato K, Hayashi T. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:5071–5075. doi: 10.1021/jo980100b. Arai MA, Kuraishi M, Arai T, Sasai H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:2907–2908. doi: 10.1021/ja005920w. Tsujihara T, Shinohara T, Takenaka K, Takizawa S, Onitsuka K, Hatanaka M, Sasai H. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:9274–9279. doi: 10.1021/jo901778a. Zhang YJ, Wang F, Zhang W. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:9208–9213. doi: 10.1021/jo701469y.

- (3).For ligand-modulated Pd-catalysts capable of using O2 as the oxidant, see: Trend RM, Ramtohul YK, Ferreira EM, Stoltz BM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:2892–2895. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351196. Trend RM, Ramtohul YK, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17778–17788. doi: 10.1021/ja055534k. Yip K-T, Yang M, Law K-L, Zhu N-Y, Yang D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:3130–3131. doi: 10.1021/ja060291x. He W, Yip KT, Zhu NY, Yang D. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5626–5628. doi: 10.1021/ol902348t. Scarborough CC, Bergant A, Sazama GT, Guzei IA, Spencer LC, Stahl SS. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:5084–5092. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.072. Jiang F, Wu Z, Zhang W. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:5124–5126.

- (4).For important advances in related enantioselective metal-catalyzed C–N bond forming reactions, see the following review and selected primary references: Chemler SR. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:3009–3019. doi: 10.1039/B907743J. Overman LE, Remarchuk TP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12–13. doi: 10.1021/ja017198n. Mai DN, Wolfe JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12157–12159. doi: 10.1021/ja106989h. Du H, Zhao B, Shi Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8590–8591. doi: 10.1021/ja8027394.

- (5).(a) Fix SR, Brice JL, Stahl SS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:164–166. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<164::aid-anie164>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu GS, Stahl SS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6328–6335. doi: 10.1021/ja070424u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ye X, Liu G, Popp BV, Stahl SS. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:1031–1044. doi: 10.1021/jo102338a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).The Pd(OAc)2/pyridine catalyst system was discovered and employed in aerobic alcohol oxidation by Uemura and coworkers: Nishimura T, Onoue T, Ohe K, Uemura S. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:6750–6755. doi: 10.1021/jo9906734.

- (7).(a) Perch NS, Widenhoefer RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:6960–6961. [Google Scholar]; (b) Perch NS, Pei T, Widenhoefer RA. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:3836–3845. doi: 10.1021/jo0003192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yoo KS, Park CP, Yoon CH, Sakaguchi S, O’Neill J, Jung KW. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3933–3935. doi: 10.1021/ol701584f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Zhang Y, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3076–3077. doi: 10.1021/ja070263u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jensen KH, Pathak TP, Zhang Y, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17074–17075. doi: 10.1021/ja909030c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pathak TP, Gligorich KM, Welm BE, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7870–7871. doi: 10.1021/ja103472a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Gsponer A, Schmid TM, Consiglio G. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2001;84:2986–2995. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lu XY, Zhang QH. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001;73:247–250. [Google Scholar]; (c) Dodd DW, Toews HE, Carneiro FD, Jennings MC, Jones ND. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2006;359:2850–2858. [Google Scholar]; (d) Schiffner JA, Machotta AB, Oestreich M. Synlett. 2008:2271–2274. [Google Scholar]; (e) Michel BW, Camelio AM, Cornell CN, Sigman MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6076–6077. doi: 10.1021/ja901212h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Absolute configuration was established by comparison of (R)- and (S)-N-tosylproline with samples synthesized by alkene oxidative cleavage of the oxidative amidation products. Refer to the Supporting Information for details.

- (12).Thus far, efforts to form six-membered heterocycles have not been successful (i.e. low yield and ee). Efforts towards this goal are ongoing.

- (13).See Supporting Information for details.

- (14).Trend RM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15957–15966. doi: 10.1021/ja804955e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.