Abstract

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) catalyzes oxidation of toxic aldehydes to carboxylic acids. Physiologic levels of Mg2+ ions influence ALDH2 activity in part by increasing NADH binding affinity. Traditional fluorescence measurements monitor the blue shift of the NADH fluorescence spectrum to study ALDH2-NADH interactions. By using time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy, we have resolved the fluorescent lifetimes (τ) of free NADH (τ = 0.4 ns) and bound NADH (τ = 6.0 ns). We used this technique to investigate the effects of Mg2+ on the ALDH2-NADH binding characteristics and enzyme catalysis. From the resolved free and bound NADH fluorescence signatures, the KD for NADH with ALDH2 ranged from 468 µM to 12 µM for Mg2+ ion concentrations of 20 µM to 6000 µM, respectively. The rate constant for dissociation of the enzyme-NADH complex ranged from 0.4 s−1 (6000 µM Mg2+) to 8.3 s−1 (0 µM Mg2+) as determined by addition of excess NAD+ to prevent re-association of NADH and resolving the real-time NADH fluorescence signal. The apparent NADH association/re-association rate constants were approximately 0.04 µM−1s−1 over the entire Mg2+ ion concentration range and demonstrate that Mg 2+ ions slow the release of NADH from the enzyme rather than promoting its re-association. We applied NADH fluorescence lifetime analysis to the study of NADH binding during enzyme catalysis. Our fluorescence lifetime analysis confirmed complex behavior of the enzyme activity as a function of Mg2+ concentration. Importantly, we observed no pre-steady state burst of NADH formation. Furthermore, we observed distinct fluorescence signatures from multiple ALDH2-NADH complexes corresponding to free NADH, enzyme-bound NADH, and, potentially, an abortive NADH-enzyme-propanal complex (τ = 11.2 ns).

Keywords: Aldehyde dehydrogenase, fluorescence, NADH

1. Introduction

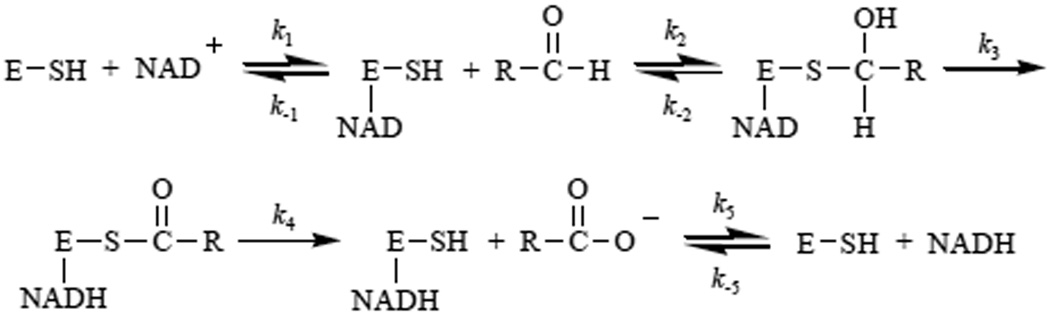

Aldehydes are produced as a consequence ethanol metabolism and from lipid peroxidation that occurs in several disease processes. Cells possess enzymes to decrease the levels of these aldehydes among which, the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) play a major role. Using NAD+ as a cofactor, these enzymes oxidize aldehydes to carboxylic acids and produce NADH by an irreversible ordered sequential mechanism involving NAD+ binding (k1), thiohemiacetal formation (k2), hydride transfer (k3), deacylation (k4) and NADH dissociation (k5) [1] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of the ALDH2 catalytic mechanism.

A considerable amount of literature has been published on the effect Mg2+ ions have on the specific activity of mitochondrial ALDHs [1–5]. The concentration of free mitochondrial Mg2+ ions in hepatic mitochondria has been estimated to be between 400 µM and 1000 µM [6,7]. The concentration of Mg2+ ions can alter ALDH activity by altering the rate limiting steps of enzyme catalysis. Furthermore, the presence of Mg2+ ions can alter the enantioselectivity of ALDH2 towards the cytotoxic aldehyde 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal [2]. Unlike many of its isozymes [1,8,9], ALDH2, has deacylation as its rate limiting step when Mg2+ ions are absent [10]. As Mg2+ ions are introduced, the overall rate of aldehyde oxidation increases until the concentration reaches near 100 µM [1]. As this Mg2+ concentration is exceeded, ALDH activity decreases owing to Mg2+-induced increases in the affinity for the NADH product whose release eventually becomes rate limiting. By decreasing the KD for NADH, the overall enzyme activity decreases [1].

The interaction of NADH with ALDH2 has been previously examined by measuring the fluorescence intensity of the NADH under static conditions using traditional fluorescence techniques [1]. Upon binding to a protein, the fluorescence spectrum of NADH shifts approximately 20 nm towards the blue, and the NADH quantum yield is generally increased fourfold [11]. These types of studies have been used to determine that Mg2+ ions increase the affinity of NADH for ALDH2.

However, real-time measurement of NADH fluorescence lifetimes (τ) can provide additional details not revealed by traditional fluorescence measurements. Free NADH has a relatively short τ of near 0.4 ns, and the lifetime increases upon binding to proteins [11]. A fluorescence-lifetime analysis allows for the differentiation of bound and unbound forms of NADH, thus giving the potential to actively monitor the enzymatic reaction during enzyme catalysis in greater detail compared to traditional fluorescence techniques.

In these current studies, we tested the hypothesis that NADH exists in multiple fluorescent states during enzyme catalysis and that these states are affected by the presence of aldehydes and Mg2+. By employing time-resolved fluorescence techniques, we have found that NADH has multiple fluorescence lifetimes in the presence of enzyme with (or without) magnesium ion and aldehyde. During enzymatic reactions in the presence of ALDH2, NAD+, aldehyde, and Mg 2+, we resolved the fluorescence signature of the NADH-ALDH2 complex from the free NADH signal and another NADH-ALDH complex indicative of an abortive E-NADH-aldehyde complex.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

NAD+ and NADH were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Propanal was purchased from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ). Magnesium chloride, electrophoresis grade EDTA (free acid), enzyme grade HEPES, and D-glycogen (beef liver) were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). The EDTA and HEPES buffer solutions were adjusted from their acidic forms to pH 7.4 using sodium hydroxide.

2.2. Preparation of recombinant rat ALDH2

Recombinant rat ALDH2 containing an N-terminal 6X histidine tag was prepared as previously described using Rosetta 2 (DE3) E. coli cells (Novagen, EMD BioSciences, San Diego, CA) [12]. Following nickel agarose affinity chromatography, purified ALDH2 was dialyzed at 4 °C versus two changes of buffer (1:1000) consisting of 0.15 M NaCl, 40 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, treated with Chelex 100, containing 100 µM DTT to preserve enzyme activity. Purity of protein at just above 50 kDa was over 95% as judged by SDS-PAGE analysis.

2.3. Time-resolved fluorescence instrument

Time-domain fluorescence data were collected with a custom instrument developed by Dakota Technologies, Inc. (Fargo, ND). The instrument is an adapted version of the Cary Eclipse steady-state fluorometer (Varian, Inc.), which has been enhanced with the addition of a pulsed laser excitation source, fast rise-time photomultiplier tube (PMT), and transient digitizer; the steady-state functionality is not affected by the modifications. The excitation source for the lifetime measurements is a JDS Uniphase NV-10410-DA1 Microchip NanoLaser (now available from Teem Photonics). Key specifications at 355 nm are 0.98 µJ pulse energy, 0.42 ns pulse width (FWHM)), and 8.01 kHz pulse repetition frequency. The laser simultaneously produces 355 nm and 532 nm light. A periscope arrangement of two dichroic mirrors was used to select the 355 nm output, which was delivered with vertical polarization to a Quantum Northwest TLC 50 temperature-controlled sample holder; a similar periscope is available to select the 532 nm excitation, also with vertical polarization. All fluorescence measurements were conducted while the solutions were stirred with a 7 mm micro stir bar and the temperature maintained at 25 °C. To eliminate anisotropy effects, the time-domain fluorescence was detected at magic angle (54.7°) polarization. The emission collection optics of the fluorometer was left untouched. The Eclipse employs a Hamamatsu R928 photomultiplier for steady-state data acquisition. A Hamamatsu R7400U-20 PMT with 0.7 ns rise-time was installed for the lifetime work. The R7400-20 PMT can be slid into place at the monochromator exit slit or moved to the side for conventional steady-state data collection. The PMT current was processed using a fast digitizer from Fluorescence Innovations (1 GS/s sampling rate, 150 MHz bandwidth, 10-bit ADC, and internal trigger) interfaced with a PC computer through the USB port.

The instrumental response function of the detection system was collected under the same condition as the sample using a scattering solution of dissolved glycogen. The fluorescence data were analyzed in a customized spreadsheet using an iterative procedure based on the Marquardt algorithm. Data were presented as the sum of the exponential components

where αi are pre-exponential amplitudes and τi are the lifetimes of the fluorescence decay components. Accuracy of fits was characterized by the reduced χ2 statistic and a plot of weighted residuals.

2.4. Wavelength-time matrix and kinetic data modes

The capability of the system to rapidly generate fluorescence decay curves with high signal-to-noise was used to collect multidimensional wavelength–time matrices (WTMs) and kinetic data. A WTM is a series of fluorescence decay curves acquired over a series of emission wavelengths. In these NADH studies, decay curves over a 100 ns time range were collected with a 5000 shot average at each wavelength as the emission monochromator was advanced from 420 nm to 545 nm in steps of 5 nm (Figure 2). Integration of the area under the decay curve converts the WTM to a conventional fluorescence spectral representation. Fluorescence spectra were not corrected for grating and PMT efficiencies so the emission maximum of free NADH (which is normally observed at 460 nm [11]) was observed at 480 nm. The emission monochromator wavelength was held constant for the kinetic studies.

Figure 2. An example wavelength-time matrix (WTM) of the NADH-ALDH2 complex.

The sample contained 1.1 µM NADH, 0.5 µM ALDH2, and 5.0 mM Mg2+ in 40 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). WTMs are used to resolve the fluorescent lifetime (τ) and emission spectrum of each contributing fluorophore.

2.5. Calibration of NADH solutions

All NADH solutions were freshly prepared and were calibrated using a CHEMUSB4-UV-VIS Ocean Optics spectrophotometer to measure the absorbance at 340 nm through sequential addition of the stock solution to 40 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) over a concentration range of 0–110 µM. WTMs containing NADH fluorescence spectral and temporal information were also collected after each sequential addition to determine a fluorescence response function. In order to obtain consistent wave profiles the fluorescence peak intensities were maintained near 50 mV by adjusting the high voltage of the PMT.

2.6. Determination of NADH dissociation constant (KD)

Similar to the NADH calibration, the dissociation constant of the ALDH2-NADH binary complex was determined through sequential addition of NADH to ALDH2 and various concentrations of MgCl2 in 40 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). As with the NADH calibrations, in these NADH binding experiments the NADH concentration range was 0–110 µM while the WTMs were collected. Over the course of seven experiments, the MgCl2 concentrations ranged from 0 to 6 mM while the ALDH2 tetrameric concentration remained at 0.50 µM. As a control, an experiment involving 40 mM EDTA was conducted and compared against the 0 mM MgCl2 results. Fluorescence data were resolved into short-lived (free NADH) and long-lived (protein-bound NADH) components. Due to limited sampling rate of our system, the fluorescence decay of free NADH fit easily to a single exponential 0.4 ns instead of the bi-exponential lifetimes near 350 and 760 ps reported with other systems [13,14]. The resulting bound NADH fluorescence intensities as a function of total NADH concentration data were fit by nonlinear regression using the one-site binding (hyperbola) equation in Prism 5 software (GraphPad) to determine the KD values.

2.7. Determination of NADH dissociation/zssociation rate constants

NADH was displaced from the binary ALDH2-NADH complex by addition of an excess amount of NAD+ (1 mM) to a solution of 3 µM ALDH2 (tetrameric), 10 µM NADH, and 0–6 mM MgCl2 in 40 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. The PMT high voltage was adjusted to maximize the initial fluorescence signal at 50 mV. Fluorescence waveforms were collected with the emission monochromator fixed at 455 nm (to maximize the NADH complex signal) and the fast digitizer set varying shot averages (145 to 5000). The relative contributions from the individual NADH fluorophores were resolved in each waveform collected to obtain the decrease in complexed NADH fluorescence intensity. To determine the NADH dissociation rate constant (k5), the decrease in complex fluorescence intensity as a function of time was modeled to first order rate behavior. In each case the NADH complex signal decreased to the level of the background fluorescence so all the E-NADH complex was presumed to have converted to E-NAD+. The apparent rate constant of NADH association with the enzyme (k−5) was calculated from the values of KD and k5.

2.8. ALDH2 activity

Enzyme activity experiments were conducted with the emission monochromator fixed at 455 nm and the PMT high voltage fixed at 700 V. Solutions of ALDH2 (0.25 µM tetrameric), NAD+ (1 mM), and MgCl2 (0–6 mM) in 40 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) were stirred until thoroughly mixed. After data collection was initiated and a starting fluorescence baseline was established, 12.5 µL of propanal (100 µM cuvette concentration) was injected into the cuvette using a pipette to initiate the reaction. The fluorescence waveforms were collected until the total fluorescence intensity reached 50 mV. Once the collected waveforms were resolved into the individual contributing NADH fluorophores, the dehydrogenase activity was determined based upon the initial rate of free NADH production. The 0 mM Mg2+ experiment was again compared to an experiment including 40 mM EDTA as a control.

3. Results

In applying time-resolved fluorescence to solutions containing NADH and ALDH2 enzyme in HEPES buffer (in the absence of Mg2+ ions), two main fluorescent contributors were apparent. The free, unbound NADH in solution had a single exponential fluorescence decay of 0.4 ns and the bound NADH had a single exponential fluorescence decay of 6.0 ns. It is not unusual for NADH to form longer-lived complexes with proteins [11,14,15]. As increasing amounts of Mg2+ ion were introduced in subsequent NADH binding experiments, the fluorescence lifetime of these two contributors did not change significantly, nor did any additional fluorescent contributors arise. A summary of our NADH dissociation results is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effect of Mg2+ on the NADH Dissociation and Association Rates with ALDH2.

| [Mg2+] | k5 | KD | k−5a |

|---|---|---|---|

| (µM) | (s−1) | (µM) | (µM−1s−1) |

| 0 | [8.3] | [468] | [0.018] |

| 20 | [4.2] | [317] | [0.013] |

| 60 | - | 119 | - |

| 200 | 1.4 | 35 | 0.040 |

| 600 | - | 16 | - |

| 2000 | 0.5 | 12 | 0.04 |

| 6000 | 0.4 | 12 | 0.03 |

k−5 = k5/KD

[ ] indicates the KD values significantly exceeded the upper NADH concentration limit reached during NADH titrations. The k5 values may be underestimated and reflect the rate of mixing rather the rate of NADH dissociation causing the k−5 values to also be underestimated.

The effect Mg2+ ion has on the rate constants for NADH dissociation (k5) and NADH association (k−5) was examined by adding an excess of NAD+ to a solution containing the binary enzyme-NADH complex with increasing concentrations of Mg 2+ [1] and monitoring the disappearance of the fluorescent signature of the binary complex. Table 1 also summarizes our kinetic results. The NADH dissociation rate decreases by 20-fold as the Mg2+ concentration was increased from 0 to 6000 µM. In dividing the rate constant for NADH dissociation (k5) by the NADH dissociation constant, we were also able to obtain the apparent rate constant for NADH association with ALDH2 (k−5). Only a minor two-fold increase in NADH association was noted with increasing Mg2+ concentration.

Given our findings through utilizing time resolved fluorescence in monitoring ALDH2-NADH interactions, we sought to apply this technique to monitor these same interactions during enzymatic catalysis, in which enzyme, aldehyde, NAD+, and Mg 2+ were present. By monitoring the production of free NADH, we noted a complex response of Mg 2+ upon enzyme activity (Fig. 3) that agrees with previous literature [1].

Figure 3. Mg2+ alters ALDH2 activity in a complex manner.

The effect of Mg2+ ion concentration on enzyme activity. Reaction mixtures contained 0.25 µM ALDH2 (tetramer), 1 mM NAD+, 100 µM propanal, and the indicated Mg2+ concentrations in 40 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4.

In resolving the remaining fluorescence contributions, it was apparent that a third fluorophore was present in solution during catalysis and has a single exponential fluorescence decay of 11.2 ns. This third fluorophore reaches a steady state concentration similar to that of the ALDH2-NADH complex (Fig. 4A). Under high aldehyde conditions (100 µM), the steady state concentration the ALDH2-NADH complex and the third fluorophore increased with increasing Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 4B). During enzyme catalysis, as the excess aldehyde is consumed, the fluorescence from the third fluorophore dramatically decreases before a decrease in fluorescence from ALDH2-NADH complex is observed or a loss of production of free NADH occurs.

Figure 4. Time-resolved fluorescence analysis of ALDH2 activity.

(A) The fluorescence waveforms collected during enzymatic catalysis are used to determine the changes in concentration of free and bound forms of NADH. In addition to the fluorescence from the free NADH (τ = 0.4 ns) and ALDH2-NADH complex (τ = 6.0 ns) observed in the KD studies, a third fluorescent contributor (τ = 11.2 ns) is resolved in the presence of Mg2+. The reaction mixture contained 0.25 µM ALDH2, 1 mM NAD+, 100 µM propanal, and 6000 µM Mg2+. (B) The effect of Mg2+ ion concentration on relative fluorescence intensities reached at steady state conditions from the ALDH2-NADH complex and third fluorescent contributor.

Static experiments were conducted in which propanal was added to solutions containing Mg2+, ALDH2, and NADH. From these experiments the third fluorophore was observed and from the WTMs collected, it is clear that fluorescence spectrum of this contributor is identical to that of the ALDH2-NADH binary complex even though fluorescence lifetimes are considerably different (Fig.5).

Figure 5. Resolved spectral and temporal contributions from WTM of a sample containing 2.9 µM NADH, 0.25 µM ALDH2, and 6.0 mM Mg2+ in 40 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4).

(A) The resolved fluorescence spectra illustrates that the third contributor has an identical fluorescent spectrum to that of the ALDH2-NADH complex. (B) The resolved temporal contributions provide a measure of the relative amounts and the fluorescence lifetime of each contributor.

Once the individual contributors to the total fluorescence observed during enzyme catalysis was resolved, it was apparent that the “burst” in fluorescence observed at significant levels of Mg2+ is a burst of protein-bound NADH formation. In the absence of Mg2+ ions we observed no “burst” behavior in NADH formation. No burst of free NADH was observed in either the presence or absence of metal.

4. Discussion

The dissociation constant for NADH with ALDH2 has been examined previously in the absence of divalent metals by measuring the increase in fluorescence intensity as NADH binds to ALDH2. From this approach, a KD value of 3 µM was reported [16]. In another report, the dissociation constant was determined as an inhibition constant (Kiq) for NADH acting as a competitive inhibitor against NAD+. From this second approach, a Kiq value of 140 µM was reported in the absence of metal, and a value of 12 µM was reported in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+ [1]. With our approach, the determination of KD values at low Mg2+ concentrations (< 60 µM) were quite difficult to obtain because the concentration of bound NADH species increases almost linearly with total NADH concentration over the limited NADH concentration range (<110 µM). Given these experimental limitations, our KD values agree reasonably well with the Kiq values at low Mg2+ concentrations, and are identical at high Mg2+ concentrations.

Our NADH binding and displacement studies showed that Mg2+ ions restrict the release of NADH from ALDH2. This result was in agreement with previous literature [1], however; our results show a considerably larger change in the rate of NADH dissociation. As stated earlier, our fluorescence results show a 20-fold decrease in the rate of NADH dissociation from ALDH2 as the Mg2+ concentration was increased from 0 to 6 mM. Previous work conducted under similar condition reported no significant change in the NADH dissociation rate constant as the Mg2+ concentration was increased from 0 to 2 mM Mg2+ and a three-fold increase when the Mg2+ concentration was increased to 5 mM. While the previous study focused on the loss of fluorescence enhancement as the NADH was displaced from ALDH2, this approach focuses on discriminating the NADH-ALDH2 fluorescent signature from the significant background fluorescence of the free NADH in solution.

Our NADH binding and displacement studies also showed that Mg2+ ions may increase the apparent rate constant for ALDH2-NADH association (k−5) by nearly two-fold. Unfortunately, at the lower Mg2+ concentrations (0 µM and 20 µM), the rate of NADH dissociation is so fast that the determined rate constant for NADH dissociation (k5) may be more a reflection of the rate of solution mixing. As such the rate constant for dissociation is most likely even faster than indicated in Table 1 thus making the rate of association constant.

Throughout all of our NADH binding studies, both in the presence and absence of Mg2+, the fluorescence lifetime of bound NADH was consistently 6.0 ns. Given the NMR/fluorescence work cited earlier [17] and other crystallographic studies [18], this consistency in the fluorescence lifetime is surprising. Fluorescence anisotropy and NMR results suggest that, although the reduced nicotinamide ring retains significant mobility after NADH formation, this mobility becomes more restricted in the presence of magnesium [17]. These studies also indicate that the nicotinamide ring becomes reoriented when Mg2+ ions were added. More recent crystallographic work [19] suggests that the presence of magnesium may play a more significant role in NAD isomerization than for NADH. Our observation of only one bound E-NADH fluorescence lifetime supports the possibility that NADH has a high conformational preference towards the hydrolysis conformation.

The apparent lack of burst behavior in the absence of magnesium clearly differs from previous reports [5,9,20,21]. A possible reason for the difference is our use of Chelex 100 resin, since trace amounts of metal ion could cause the appearance of low levels of burst magnitude reported in these studies. However, as stated earlier, this burst observed is due to the immediate formation of protein-bound NADH, not free NADH.

At significant levels of Mg2+ and propanal, the fluorescence of protein-bound NADH was comprised of two distinct fluorescent contributors (6.0 ns and 11.2 ns lifetimes). The 11.2 ns contributor is not observed in the absence of Mg2+. Therefore, the signature is not attributed to the acylated ALDH2-NADH complex. This longer lived fluorescence contributor may be an aldehyde-ALDH2-NADH adduct (Figure 6). One explanation for this would be that at higher Mg2+ ion concentrations, when the rate of NADH dissociation has been significantly decreased, ample opportunity would be provided for the enzyme-NADH adduct present to acquire aldehyde into some of the vacant substrate binding sites. With the aldehyde drawn into close proximity with restricted NADH, a change in the fluorescence lifetime of the NADH is observed. This hypothesis was tested by conducting static experiments in which varying amounts of magnesium, NADH, and propanal were introduced to the ALDH system. The long lived fluorophore (11.2 ns) was only observed when significant amounts of all three components were added to ALDH.

Figure 6. Proposed schematic of ALDH2-NADH-propanal abortive ternary complex in the presence of Mg2+.

In conclusion, this work demonstrates that as Mg2+ is introduced in the ALDH2 system and the release of NADH from the enzyme is restricted, the buildup of binary complex is responsible for the burst in fluorescence signal previously reported and not due to a burst of free NADH in solution. As the Mg2+ concentration increases the rate limiting step changes from deacylation to NADH dissociation, adequate time is available for propanal to enter the active site of the binary complex and form a reversible abortive NADH-enzyme-propanal complex.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grant P20 RR016471–08 (INBRE) from the NCRR. We also thank Dr. Gregory Gillispie for his helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ho KK, Alli-Hassani A, Hurley TD, Weiner H. Differential effects of Mg2+ ions on the individual kinetic steps of human cytosolic and mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenases. Biochemistry. 2005;44:8022–8029. doi: 10.1021/bi050038u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brichac J, Ho KK, Honzatko A, Wang R, Lu X, Weiner H, Picklo MJ., Sr Enantioselective oxidation of trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is aldehyde dehydrogenase isozyme and Mg2+ dependent. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:887–895. doi: 10.1021/tx7000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang SL, Wu CW, Cheng TC, Yin SJ. Isolation of high-Km aldehyde dehydrogenase isoenzymes from human gastric mucosa. Biochem. Int. 1990;22:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett AF, Buckley PD, Blackwell LF. Inhibition of the dehydrogenase activity of sheep liver cytoplasmic aldehyde dehydrogenase by magnesium ions. Biochemistry. 1983;22:776–784. doi: 10.1021/bi00273a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Weiner H. Magnesium stimulation of catalytic activity of horse liver aldehyde dehydrogenase. Changes in molecular weight and catalytic sites. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:8206–8209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corkey BE, Duszynski J, Rich TL, Matschinsky B, Williamson JR. Regulation of free and bound magnesium in rat hepatocytes and isolated mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:2567–2574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenzen S, Hickethier R, Panten U. Interactions between spermine and Mg2+ on mitochondrial Ca2+ transport. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:16478–16483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann CJ, Weiner H. Differences in the roles of conserved glutamic acid residues in the active site of human class 3 and class 2 aldehyde dehydrogenases. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1922–1929. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.10.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwell LF, Motion RL, MacGibbon AK, Hardman MJ, Buckley PD. Evidence that the slow conformation change controlling NADH release from the enzyme is rate-limiting during the oxidation of propionaldehyde by aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 1987;242:803–808. doi: 10.1042/bj2420803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman RI, Weiner H. Horse liver aldehyde dehydrogenase. II. Kinetics and mechanistic implications of the dehydrogenase and esterase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1972;247:267–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. second ed. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leiphon LJ, Picklo MJ., Sr Inhibition of aldehyde detoxification in CNS mitochondria by fungicides. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vishwasrao HD, Heikal AA, Kasischke KA, Webb WW. Conformational dependence of intracellular NADH on metabolic state revealed by associated fluorescence anisotropy. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:25119–25126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Q, Heikal AA. Two-photon autofluorescence dynamics imaging reveals sensitivity of intracellular NADH concentration and conformation to cell physiology at the single-cell level. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2009;95:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Johnson ML. Fluorescence lifetime imaging of free and protein-bound NADH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:1271–1275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh S, Ni L, Hurley TD, Weiner H. The potential roles of the conserved amino acids in human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18817–18822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammen PK, Allali-Hassani A, Hallenga AK, Hurley TD, Weiner H. Multiple conformations of NAD and NADH when bound to human cytosolic and mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7156–7168. doi: 10.1021/bi012197t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perez-Miller SJ, Hurley TD. Coenzyme isomerization is integral to catalysis in aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7100–7109. doi: 10.1021/bi034182w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu ZJ, Sun YJ, Rose J, Chung YJ, Hsiao CD, Chang WR, Kuo I, Perozich J, Lindahl R, Hempel J, Wang BC. The first structure of an aldehyde dehydrogenase reveals novel interactions between NAD and the Rossmann fold. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:317–326. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farres J, Wang X, Takahashi K, Cunningham SJ, Wang TT, Weiner H. Effects of changing glutamate 487 to lysine in rat and human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. A model to study human (Oriental type) class 2 aldehyde dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:13854–13860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner H, Hu JH, Sanny CG. Rate-limiting steps for the esterase and dehydrogenase reaction catalyzed by horse liver aldehyde dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 1976;251:3853–3855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]