Abstract

The diaphragm muscle is main inspiratory muscle in mammals. Quantitative analyses documenting the reliability of chronic diaphragm EMG recordings are lacking. Assessment of ventilatory and non-ventilatory motor behaviors may facilitate evaluating diaphragm EMG activity over time. We hypothesized that normalization of diaphragm EMG amplitude across behaviors provides stable and reliable parameters for longitudinal assessments of diaphragm activity. We found that diaphragm EMG activity shows substantial intra-animal variability over 6 weeks, with coefficient of variation (CV) for different behaviors ~29–42%. Normalization of diaphragm EMG activity to near maximal behaviors (e.g., deep breathing) reduced intra-animal variability over time (CV ~22–29%). Plethysmographic measurements of eupneic ventilation were also stable over 6 weeks (CV ~13% for minute ventilation). Thus, stable and reliable measurements of diaphragm EMG activity can be obtained longitudinally using chronically implanted electrodes by examining multiple motor behaviors. By quantitatively determining the reliability of longitudinal diaphragm EMG analyses, we provide an important tool for evaluating the progression of diseases or injuries that impair ventilation.

Keywords: Respiration, Motor Unit Recruitment, Ventilation, Hypoxia, Hypercapnia, Neuromotor control (max 6)

1. Introduction

As the major inspiratory pump muscle in mammals, the diaphragm muscle is of particular importance in the neuromotor control of respiration (Sieck, 1991). Many studies have examined diaphragm activity in anesthetized and freely moving animals usually by recording electromyographic (EMG) activity (Mantilla et al., 2010; Trelease et al., 1982). Assessments of ventilatory muscle activity are clearly important in evaluating the progression of and recovery from disease or injury (Mantilla and Sieck, 2003, 2008, 2009; Sieck and Mantilla, 2009). However, simple measures of diaphragm EMG activity (e.g., average rectified integrated (Dow et al., 2006; Dow et al., 2009) or root- mean-squared (RMS) amplitude (Mantilla et al., 2010; Sieck and Fournier, 1990) show substantial variability across animals complicating quantitative, longitudinal assessments of ventilatory activity. Furthermore, although previous techniques were reported for chronic recordings of diaphragm EMG activity in cats (Trelease et al., 1982), rabbits (Shafford et al., 2006) and guinea pigs (Chang and Harper, 1989), longitudinal, quantitative analyses documenting the reliability of such measurements are lacking.

In mammals, the diaphragm muscle is activated during ventilatory behaviors (e.g., normal resting breathing – eupnea - and exercise-induced hyperventilation) as well as during non-ventilatory behaviors associated with airway clearance (e.g., airway occlusion and sneezing)(Mantilla et al., 2010; Sieck and Fournier, 1989). Importantly, diaphragm EMG measurements reflect differences in force (Eldridge, 1975; Mantilla et al., 2010; Sieck and Fournier, 1989). Over time, a number of factors may cause variability in EMG amplitude including electrode movement, dislodgment or failure, peri-electrode tissue scarring and fibrosis as well as muscle fiber growth. Such factors may thus further complicate longitudinal assessments of ventilatory activity using EMG recordings. However, assessment of diaphragm EMG activity across ventilatory and nonventilatory behaviors may allow comparisons across recording sessions. In particular, we recently reported that spontaneous deep breaths (“sighs”) consistently produce near maximal diaphragm activation (Mantilla et al., 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that normalization of diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude with respect to deep breaths provides a stable and reliable parameter for the longitudinal assessments of diaphragm muscle activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Eleven Sprague-Dawley adult male rats (3 months of age) with an initial body weight of ~300g were used in the present study. All procedures were in accordance with the American Physiological Society Animal Care Guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (90mg/kg) and xylazine (10mg/kg) via intramuscular injection for all surgical procedures and experimental measurements.

2.2. Intramuscular diaphragm EMG

Procedures for electrode placement and recording of intramuscular diaphragm EMG were based on previously described techniques (Dow et al., 2006; Mantilla et al., 2010; Sieck and Fournier, 1990; Trelease et al., 1982). Briefly, insulated stainless steel fine wire (AS631, Cooner Wire Inc., Chatsworth, CA) was stripped ~3 mm to make electrodes. Two pairs of electrodes were implanted and fixed in each side of the mid-costal diaphragm muscle with an inter-electrode distance of ~3 mm. The electrode pairs were tunneled and externalized in the dorsum of the animal and used for chronic EMG recordings for up to 6 weeks. A loop of electrode wire was left both under the skin at the laparotomy site and in the dorsum to allow for animal movement. Baseline diaphragm EMG recordings were obtained 4 days following electrode implantation (defined as day 0, D0). Further recordings were performed at the following time-points: D7, D14, D28 and D42.

During each EMG recording session, each pair of diaphragm muscle electrodes were amplified (gain: 2000×) and band-pass filtered (20–1000 Hz). The signal was digitized using a data acquisition board with a sampling frequency of 2000 Hz and recorded using a custom made program (LabView 8.2, National Instruments Corp., Austin, TX). To assess the amplitude of diaphragm EMG activation, we calculated root-mean-squared (RMS) EMG signal, which is defined as with a window size of 50 ms. Other parameters such as burst duration, respiratory rate and duty cycle were determined using the RMS EMG signal.

2.3. Experimental behaviors

Diaphragm EMG activity was recorded during four different behaviors in the following order: (1) eupnea for ~2 min; (2) hypoxia-hypercapnia (10% O2 and 5% CO2) for ~5 min; (3) airway occlusion via forced closure of the airway for ~ 40 s; and (4) sneezing induced by intranasal infusion of 15 μl of 30 mM capsaicin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). In all cases, 5–10 min were allowed between behaviors during which a normal eupneic breathing pattern was restored. For each of these behaviors, EMG RMS amplitude was averaged during the entire eupnea or hypercapnia-hypoxia exposure and during the last 10 s of the 45 s airway occlusion. During sneezing, only peak values were used. This protocol is identical to that used in a recent study (Mantilla et al., 2010). In a subset of animals, non-invasive measurements of arterial oxygenation (MouseOX, Starr Life Sciences Corp., Oakmont, PA) verified that hemoglobin oxygen saturation returned to baseline during the recovery period between behaviors. Sporadic large breaths (“sighs” or deep breaths) were also evident during spontaneous ventilatory behaviors. Deep breaths were defined as individual breaths with EMG RMS amplitude at least two-fold greater than the average of eupneic breaths, consistent with our recent findings (Mantilla et al., 2010). Table 1 shows the ventilatory behaviors analyzed during each session.

Table 1.

Ventilatory and non-ventilatory motor behaviors of the diaphragm muscle examined during the 6-week study in adult rats.

| Time (days) | Eupnea | Hypoxia (10% O2)-Hypercapnia (5% CO2) | Airway Occlusion | Sneezing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | x | x | x | x |

| 7 | x | x | ||

| 14 | x | x | x | x |

| 28 | x | x | ||

| 42 | x | x | x | x |

2.4. Ventilatory Parameters

In a subset of rats (n=4), ventilatory parameters including tidal volume (TV), respiratory rate (RR), inspiratory and expiratory duration were also recorded using a whole body plethysmography system (Buxco Inc., Wilmington, NC). Prior to each recording, a calibration procedure was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Ventilatory parameters were measured during eupnea at the same time points just prior to diaphragm EMG recordings.

2.5. Statistical analyses and power calculation

All analyses were performed using JMP statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Comparisons were conducted using repeated measures MANOVA with time and behavior as grouping variables. When appropriate, post hoc analyses were conducted using the Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference (HSD) test. For comparisons across specific time-points, matched-pair analyses were conducted (two-tailed t-test). Statistical significance was established at the 0.05 level. Data were clustered by behavior and time-point for each animal. Thus, all experimental data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) across animals, unless otherwise specified. For each animal and behavior, a coefficient of variation (CV) was also calculated over time as the ratio of the standard deviation of mean EMG RMS amplitude for each time point divided by the mean EMG RMS amplitude for all time points. Thus, this CV represents an index of the stability of measurements over time.

A prospective power analysis was completed using a pilot group of 3 animals. When EMG RMS data was normalized to eupnea at D0, we found that a sample size of 8 would provide 77% power to detect an effect size of 0.65, assuming a standard deviation 3 times higher than that observed (α=0.05). Longitudinal comparisons over the 6-week experimental study were conducted in 8 animals for which a complete data set was obtained. In some instances, electrodes needed to be re-externalized and these diaphragm EMG recordings were censored from subsequent longitudinal analyses but were considered for across behavior comparisons within an experimental session (i.e., time point). The number of diaphragm EMG recordings used in all comparisons (a maximum of 16) is thus explicitly stated.

3. Results

EMG electrodes were successfully implanted in all 11 animals. In most animals, electrodes in either the right or left side required re-externalization due to animal biting/pulling. These electrode pairs could no longer be accessed externally, but all of them were available for diaphragm EMG recordings following surgical re-exposure. However, these recordings were censored from subsequent longitudinal analyses in order to eliminate any effect of a possible change in electrode configuration resulting from this additional surgery. Overall, 10 diaphragm sides (n=8 animals) were available for the entire 6-week period without any re-exposure.

Animals grew as expected from an average body weight of 295±4 g prior to electrode implantation to 392±11 g at D42. At D0 (4 days post-implantation), average weight decreased slightly to 286±5 g but subsequently weight increased progressively (e.g., 333±5 g at D14) with an average weight gain of ~2 g/day overall.

3.1. Diaphragm EMG amplitude over 6 weeks

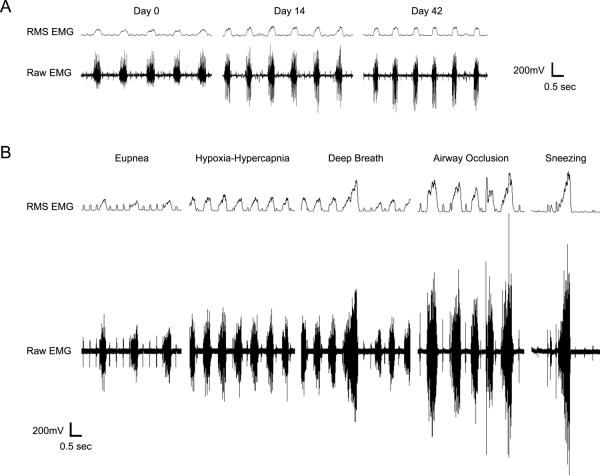

Representative diaphragm EMG recordings and RMS EMG amplitude obtained at D0, D14 and D42, and across ventilatory and non-ventilatory motor behaviors at D42 are shown in Figure 1. Consistent with a previous report in adult rats (Mantilla et al., 2010), RMS EMG amplitude increased during airway occlusion and sneezing compared to eupnea and hypoxia-hypercapnia. Also, sporadic deep breaths (i.e., “sighs”) were evident during spontaneous breathing conditions (i.e., eupnea and hypoxia-hypercapnia) in all animals. These deep breaths were relatively infrequent (~once every 4–5 min) but approximated peak RMS EMG amplitude evident during airway occlusion.

Figure 1.

Representative electromyographic (EMG) recordings and root-mean-squared (RMS) amplitude from the diaphragm muscle in an adult rat. Recordings were obtained using chronically implanted electrodes during eupnea in the same animal at day 0 (D0), D14 and D42 (A). Notice that diaphragm EMG activity occurs in bursts, reflecting rhythmic inspiration in this anesthetized animal. Minimal variability in diaphragm RMS EMG activity was observed within each recording session. Diaphragm EMG activity was also measured across the following ventilatory and non-ventilatory motor behaviors: eupnea, hypoxia-hypercapnia (10% O2- 5% CO2), airway occlusion and sneezing induced by intranasal capsaicin administration. Representative recordings obtained in a single animal at D42 are shown (B). Diaphragm EMG activity and RMS EMG amplitude increases significantly from ventilatory behaviors to nonventilatory behaviors, consistent with previous results (Mantilla et al., 2010).

For all animals, peak RMS EMG amplitude was consistent within each behavior at each time point (CV <12%). The peak RMS EMG amplitude for all behaviors and time points is presented in Table 2. There was an effect of time on RMS EMG amplitude (p<0.001) as well as an interaction between time vs. behavior (p=0.044). In post hoc analyses, RMS EMG amplitude did not change significantly over time for eupnea, hypoxia-hypercapnia and deep breaths (p>0.05). However, RMS EMG amplitude for airway occlusion and sneezing was increased at D14 compared to D0 (p=0.003 and p=0.02, respectively). For each behavior, RMS EMG amplitude displayed substantial variability over time. Mean (±SE) intra-animal CV across time was 29±5% for eupnea, 34±4% for hypoxia-hypercapnia, 39±6% for deep breaths, 42±5% for airway occlusion and 40±5% for sneezing. Diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude may be normalized for each animal and also for each time-point. These alternative ways of normalization are addressed in the following sections.

Table 2.

Diaphragm muscle root-mean-squared (RMS) electromyographic activity (in mV) during ventilatory and non-ventilatory behaviors over the 6-week experimental study.

| Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 28 | Day 42 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eupnea | 140±18 | 184±19 | 181±21 | 120±25 | 138±18 |

| Hypoxia-Hypercapnia | 180±23 | 238±25 | 203±31 | ||

| Deep breaths | 384±58 | 575±59 | 524±62 | ||

| Airway occlusion | 309±37 | 572±63* | 441±60 | ||

| Sneezing | 442±52 | 498±89 | 743±65* | 430±66 | 593±141 |

Results are mean ± SE.

significant difference compared to Day 0 (p<0.05).

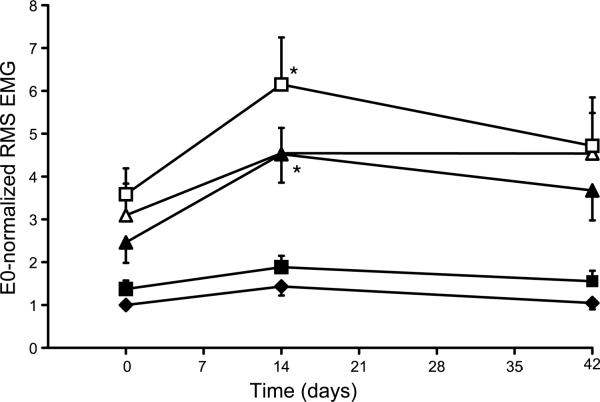

3.2. Normalized RMS EMG Over 6 Weeks

First, diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude at each time point was normalized to the eupneic value at D0 (E0-normalization) for the same animal. As expected, there was still a significant effect of time on E0-normalized RMS EMG amplitude over the 6-week experimental study (p<0.0001), although there no longer was an interaction between time vs. behavior (p=0.14). For eupnea, hypoxia-hypercapnia or deep breaths (Figure 2), RMS EMG amplitude did not change significantly over time (p>0.05 in all cases), but a significant increase in RMS EMG amplitude was still observed during occlusion and sneezing at D14 compared to D0 (p=0.003 and p=0.03, respectively).

Figure 2.

Amplitude of diaphragm RMS EMG activity across different ventilatory and nonventilatory behaviors, normalized to eupnea at D0 (E0-normalization). Diaphragm EMG RMS amplitude measured at 3 different time points: D0, D14, and D42 and across 5 different motor behaviors at each time-point are shown (eupnea: ◆ hypoxia-hypercapnia: ■; deep breath: Δ; airway occlusion: ▲; sneezing: □). No significant changes in peak RMS EMG amplitude were observed over 6 weeks during eupnea, hypoxia-hypercapnia or deep breaths. During occlusion and sneezing, there was a significant effect of time: E0-normalized EMG amplitude at D14 was greater than at D0. Equivalent results are obtained when normalizing to sneezing at D0 (data not shown). All data are mean ± SE (n=8 animals; 10 electrode pairs).

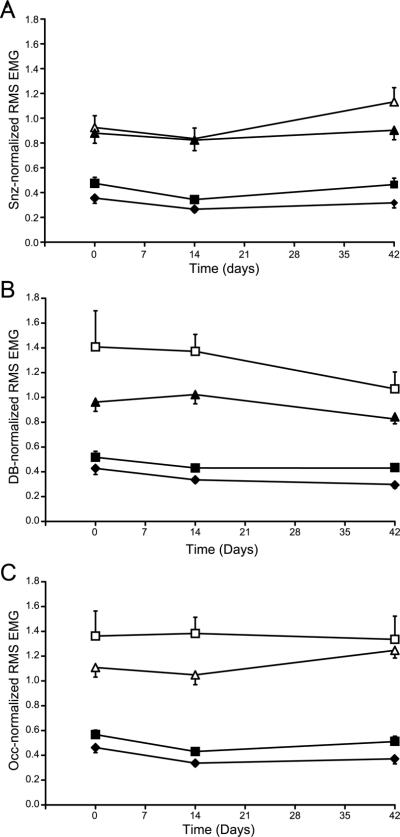

Second, diaphragm RMS EMG values for each time point were normalized to the RMS EMG amplitude recorded during sneezing at that time point (Snz-normalization). Because data were normalized within the same experimental session, all EMG recordings obtained from all sides were used in this analysis (n=16). Figure 3A shows eupneic diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude normalized to sneezing at the same time point. There was no significant effect of time on Snz-normalized RMS EMG amplitude over the 6-week experimental study (p=0.08) and no interaction between time vs. behavior (p=0.84). The CV in Snz-normalized RMS EMG amplitude was 43±5% for eupnea, 34±5% for hypoxia-hypercapnia, 40±3% for deep breaths and 33±5% for airway occlusion. Apparent changes in the capsaicin response over time may have contributed to this variability, possibly reflecting a change in capsaicin sensitivity resulting from repeated exposures.

Figure 3.

Amplitude of diaphragm RMS EMG activity was normalized within the same time-point to that during sneezing (Snz-normaliztion; A), deep breaths (DB-normalization; B) and sustained airway occlusion (Occ-normalization; C). Notice stable measurements across behaviors (eupnea: ◆ hypoxia-hypercapnia: ■; deep breath: Δ; airway occlusion: ▲; sneezing: □). There was no significant effect of time on Snz-, DB- or Occ-normalized RMS EMG amplitude over the 6-week experimental study and no interaction between time vs. behavior. However, the CV for each behavior was reduced in DB- and Occ-normalized compared to Snz-normalized data (see text for details). All data are mean ± SE (n=8 animals; 16 electrode pairs).

Thus, we also examined normalization to diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude during deep breaths (DB-normalization) or airway occlusion (Occ-normalization) since we previously showed that these behaviors could generate diaphragm EMG activity ~65% of maximal (Mantilla et al., 2010). There was an effect of time on DB-normalized RMS EMG amplitude over the 6-week experimental study (p=0.048), but no interaction between time vs. behavior (p=0.58). In post hoc analyses, there was no significant difference over the 6-week study in DB-normalized RMS EMG amplitude during eupnea, hypoxia-hypercapnia, airway occlusion or sneezing (p>0.05 for all behaviors; Figure 3B). Of note, using the DB-normalized RMS EMG amplitude reduced the CV across all time points for all behaviors except for sneezing (CV: 29±6% for eupnea, 24±4% for hypoxia-hypercapnia, 22±3% for airway occlusion and 41±4% for sneezing). Following Occ-normalization (Figure 3C), there was no significant difference in RMS EMG amplitude over the 6-week study (p=0.30) and no interaction between time vs. behavior (p=0.86). The CV in Occ-normalized RMS EMG amplitude was 26±4% for eupnea, 20±3% for hypoxia-hypercapnia, 20±2% for deep breaths and 35±4% for sneezing. Thus normalization to near maximal behaviors such as deep breathing or airway occlusion results in much improved intra-animal variability over time and could be used to obtain reliable EMG analyses with chronically implanted diaphragm electrodes.

3.3. Ventilatory Parameters

Ventilatory parameters measured from diaphragm RMS EMG included respiratory rate, burst duration and duty cycle (Table 3). As expected, respiratory rate was higher during hypoxiahypercapnia compared to eupnea at all time-points (p<0.05 for all pairwise comparisons). At each time point, burst duration was higher for motor behaviors of increasing demand, i.e., airway occlusion, deep breaths and sneezing, compared to ventilatory behaviors such as eupnea and hypoxia-hypercapnia. Duty cycle was calculated as the percent time with EMG activity. Duty cycle during hypoxia-hypercapnia was increased compared to eupnea at all time points (p<0.05). There was no effect of time on respiratory rate, burst duration or duty cycle across the different ventilatory behaviors (p>0.05 in all cases).

Table 3.

Ventilatory parameters derived from diaphragm muscle EMG recordings obtained during ventilatory and non-ventilatory motors behaviors over 6 weeks.

| Behavior | Parameter | Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 28 | Day 42 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eupnea | Respiratory rate (min;−1) | 62±3 | 74±5 | 66±3 | 73±4 | 58±5 |

| Burst duration (ms) | 296±13 | 269±9 | 260±11 | 274±12 | 320±24 | |

| Duty cycle (%) | 30±1 | 34±2 | 30±1 | 33±3 | 30±2 | |

| Hypoxia-Hypercapnia | Respiratory rate (min−1) | 81±6 | 93±4 | 102±7 | ||

| Burst duration (ms) | 308±14 | 282±5 | 307±15 | |||

| Duty cycle (%) | 40±4 | 44±3 | 53±3 | |||

| Deep breaths | Burst duration (ms) | 486±79 | 531±22 | 589±32 | ||

| Airway occlusion | Burst duration (ms) | 690±180 | 528±37 | 487±24 | ||

| Sneezing | Burst duration (ms) | 677±119 | 560±57 | 682±54 | 574±54 | 657±101 |

Results are mean ± SE. No significant differences were evident across time for the same ventilatory parameter.

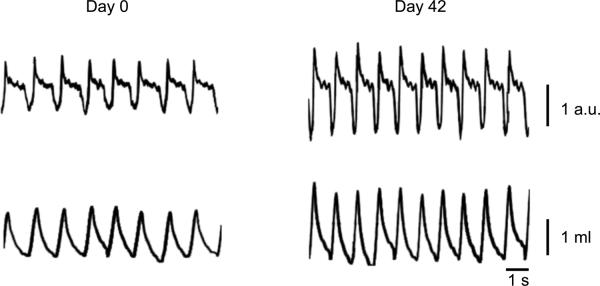

Plethysmographic measurements of ventilatory parameters were also obtained in a subset of animals during eupnea (n=4; Table 4). Respiratory rate was stable over the 6 week experimental period (p>0.05). Inspiratory duration (Ti) and expiratory duration (Te) also did not change over 6 weeks (p=0.553 and p=0.671, respectively). Accordingly, Ti:Ttot was also stable over 6 weeks (p=0.699). Tidal volume (in ml) increased in all animals by D42 compared to D0 (37% on average; Figure 4). Of note, the increase in tidal volume was proportional to the increase in body weight; thus, normalized tidal volume remained stable (~ 4 ml/kg) during the 6-week study (Table 4). Similarly, when minute volume was corrected for body weight, it increased only slightly by D42 compared to D0 (9% on average). The CV over time for ventilatory frequency, tidal volume (normalized to body weight), and minute ventilation were 21±7%, 13±4% and 13±6%, respectively.

Table 4.

Ventilatory parameters obtained from plethysmographic measurements during eupnea over 6 weeks.

| Parameter | Day 0 | Day 14 | Day 42 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory rate (min−1) | 66±6 | 79±10 | 70±4 |

| Tidal volume (ml·kg−1) | 4.3±0.2 | 3.9±0.2 | 4.3±0.3 |

| Minute ventilation (ml· kg−1·min−1) | 277±17 | 304±28 | 302±20 |

| Inspiratory time (%; Ti:Ttot) | 28±2 | 33±4 | 28±1 |

Results are mean ± SE. Tidal volume and minute ventilation were normalized to body weight. No significant differences were evident across time for the same ventilatory parameter.

Figure 4.

Representative plethysmographic traces measured at D0 and D42 in an anesthetized rat during eupnea. Traces show box flow measurements (arbitrary units, a.u.) and calculated tidal volumes. Measurements were performed immediately before EMG recordings (see text for details). Notice increase in tidal volume at the end of the 6-week experimental period, which was proportional to changes in body weight.

4. Discussion

In this 6-week study, we found that diaphragm EMG amplitude shows substantial intra-animal variability across time (CV: 29–42% for the different ventilatory and non-ventilatory behaviors). Plethysmographic measurements of ventilatory parameters were stable during eupnea (CV: 13% for minute ventilation). Consistent with our hypothesis, normalization of diaphragm EMG activity to near maximal behaviors such as deep breathing results in much reduced intra-animal variability over time (22–29%). Thus, this type of analysis can be used to facilitate EMG analyses using chronically implanted diaphragm electrodes, although it may not be possible to discern small changes in inspiratory activity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantitatively determine the reliability of diaphragm EMG analyses over time, providing an important tool for evaluating the progression of and recovery from diseases or injuries that impair ventilation.

Longitudinal assessments of EMG activity have been reported previously, although mostly for evaluation of presence of activity rather than quantitative changes in activity levels over time. Chronic intramuscular EMG measurements were reported previously for the diaphragm muscle in cats (Schoolman and Fink, 1963; Trelease et al., 1982), rabbits (Shafford et al., 2006), rats (Weinstein et al., 1967) and fetal lambs (Cooke et al., 1990). Chronic EMG measurements have also been reported for the soleus, gastrocnemius and tibialis anterior muscles in cats and rats (Alford et al., 1987; Prochazka et al., 1976) and multiple forelimb muscles in macaque monkeys (Park et al., 2000). Indeed, in a few studies, the level of EMG activity was assessed by measuring the amplitude and number of “turns” in the EMG signal (i.e., the number of spikes in the signal) following hindlimb suspension, but these measurements are truly only semi-quantitative permitting assessment of periods of high vs. low levels of activity (Alford et al., 1987; Blewett and Elder, 1993). In previous studies, qualitative analyses of diaphragm EMG activity were also possible (Chang and Harper, 1989; Shafford et al., 2006; Trelease et al., 1982); however, quantitative analyses of EMG activity within respiratory muscles may be particularly useful in longitudinal studies. Importantly, none of these previous studies reported quantitative assessments of diaphragm EMG activity using chronically implanted electrodes.

4.1. Factors Contributing to Variability in RMS EMG Amplitude

In the present study, variability in RMS EMG amplitude within a recording session was low in all animals, e.g., during eupnea the CV was ~10%. However, between different recording sessions variability was high (e.g., 29% for eupnea and 42% for airway occlusion). There are multiple factors that may contribute to variability in the recorded EMG signal over time. One factor is electrode dislodgement or movement. The implantation technique used in this study minimizes changes in electrode position by suturing the electrode to the diaphragm muscle on each side of its exposed portion. However, the externalized portion of the electrode was susceptible to breakage or being bitten by the animal, resulting in only 10 (out of 16) pairs of diaphragm electrodes being available for all recordings during the 6-week experimental study. An alternative externalization technique, e.g., securing the wires at the skull or using a solid connector, might have prevented animal access to the electrode wires. Importantly, at the terminal experiment, there was no evidence of electrode dislodgement and recordings were obtained from all electrode pairs once the electrode wire was accessed under the skin. Furthermore, there was no consistent attenuation of signal strength.

Scarring and fibrosis around the electrodes might change in RMS EMG amplitude over time. In our study, there was no macroscopic evidence of electrode fibrosis, consistent with previous studies showing a lack of histologic damage to the diaphragm muscle, although these studies used electrodes of different configurations (Chang and Harper, 1989; Shafford et al., 2006; Trelease et al., 1982). Furthermore, inspection of diaphragm excursion after laparotomy at the terminal experiment did not indicate the presence of retractions or abnormal movement suggestive of localized scarring.

Another factor which can influence the stability of EMG amplitude over time is muscle fiber growth. During the 6-week experimental period, animals gained ~33% of body weight and this is likely associated with a proportionate increase in diaphragm muscle mass and fiber cross-sectional area. A change in muscle fiber cross-sectional area would affect the amplitude of motor unit action potentials and therefore the EMG amplitude because of changes in sampling of different motor units with chronically-implanted electrodes.

In this study, EMG recordings were quantified in anesthetized animals, although recordings were possible in awake, gently restrained animals. Alertness, anxiety and depth of anesthesia clearly influence ventilation. Thus, we restricted quantitative comparisons to recordings in anesthetized animals that were injected a consistent dose of anesthetic agents and in whom anesthesia was assessed qualitatively by checking reflex responses to mildly noxious stimulation (e.g., toe pinch). Furthermore, plethysmographic measurements of ventilatory parameters were stable just prior to EMG recordings. Although ventilatory measurements were in general agreement with previous studies using this technique (McGuire et al., 2008; McGuire et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2005), the generally lower values in the present study may reflect the anesthetized vs. awake state. At this time it is not possible to unambiguously ascertain anesthetic depth and control for any anesthetic effects on ventilation across recording sessions. Regardless, by normalizing RMS EMG amplitude to near maximal behaviors such as deep breaths allows stable and reliable measurements of diaphragm activity over time.

4.2. Measurements of diaphragm EMG across motor behaviors

In a recent study in adult rats, we found that transdiaphragmatic pressure (Pdi), which approximates force generated by the diaphragm muscle, is tightly correlated to peak RMS EMG amplitude (r2=0.78) across different motor behaviors (Mantilla et al., 2010). Consistent with previous results in cats and hamsters (Fournier and Sieck, 1988; Sieck, 1991, 1994; Sieck and Fournier, 1989), Pdi increased progressively across behaviors in the following order: eupnea, hypoxia-hypercapnia and sustained airway occlusion. Sneezing induced by intranasal capsaicin resulted in a Pdi equivalent to maximal Pdi elicited by bilateral phrenic nerve stimulation (Mantilla et al., 2010); thus, peak RMS EMG amplitude during sneezing was considered to be maximal in the present study. Consistent with the changes in Pdi across behaviors, diaphragm RMS EMG activity increases progressively, and this progression was largely maintained over time in the present study. However, there were time-dependent changes in sneezing such that for example, at D42, sneezing did not generate maximal electrical activation in some animals, and it generated lower electrical activation than airway occlusion or deep breaths. This variability in the sneezing response to capsaicin may reflect a change in capsaicin sensitivity over time (e.g., tachyphylaxis).(Bolcskei et al., 2010)

Another aspect that is worth noting is that by studying multiple motor behaviors, it may be possible to enhance measurement of changes in response to injury or disease. For instance, in the spinal cord injury model of C2 hemisection, increasing inspiratory drive (e.g., with hypoxia or hypercapnia) results in evident phrenic nerve activity that is not consistently observable at rest (Fuller et al., 2009; Golder et al., 2001; Nantwi et al., 1999; Teng et al., 1999). However, hypoxia-hypercapnia only results in ~40% of maximal RMS EMG amplitude (this study and (Mantilla et al., 2010)). In this regard, spontaneous deep breaths (sighs) represent a higher level of inspiratory activity (~65% of maximal), thus providing a greater in range in behaviors. Clearly, it will be important to also independently measure diaphragm force or pressure generation, especially since the maximal force might be reduced with injury.

4.3. Comparison of Normalization Procedures

First, we normalized diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude to eupnea or other behaviors at D0. Comparisons across time points can be made using such a normalization method. It can provide a better comparison over time. However, intra-animal variability is not affected by this normalization method. Thus, normalization to an initial behavior (e.g., eupnea or sneezing) did not improve the stability of diaphragm EMG recordings for that behavior.

We normalized RMS EMG amplitude within each time point with respect to maximal and near maximal behaviors including sneezing, deep breaths and airway occlusion. Snz-normalization did not improve intra-animal variability likely as a result of a change in the response to capsaicin. In contrast, DB- and Occ-normalization provided reduced intra-animal variability over time allowing for more reliable analysis of diaphragm EMG activity. Normalization to near maximal behaviors provided similar results, but in longitudinal studies repeated exposure to sustained airway occlusion might be detrimental to the animal's well being. Because deep breaths are observed spontaneously during both eupnea and hypoxia-hypercapnia, we propose that such normalization might prove most useful in longitudinal analyses of diaphragm EMG activity. Furthermore, the frequency of deep breaths may be increased under hypoxic conditions (Bell and Haouzi, 2010). Thus, consistent with our hypothesis, normalization of diaphragm EMG amplitude with respect to deep breaths provides a stable parameter for longitudinal assessments of diaphragm muscle activity, and, by exposure to hypoxia-hypercapnia, the frequency of deep breaths increases such that they can be reliably used in such assessments.

4.4. Conclusions

Electromyography is a common tool used to assess muscle activation in studies examining neuromotor control of breathing. Chronic recordings of diaphragm EMG activity are potentially useful in evaluating the progression of or recovery from pathological conditions or injury resulting in impaired ventilation. However, substantial variability across animals permits only qualitative analyses over time when using raw measures of EMG amplitude (e.g., RMS). By examining diaphragm EMG activity across behaviors, additional analyses are possible. Indeed, quantitatively stable and reliable measurements of peak diaphragm RMS EMG amplitude were possible using chronically implanted electrodes over 6-weeks in adult rats. This information is useful for evaluating the extent of motor recovery in conditions of disease or injury, including for instance following spinal cord injury.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (grants AR051173 and HL096750), the Paralyzed Veterans of America Research Foundation and Mayo Clinic.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alford EK, Roy RR, Hodgson JA, Edgerton VR. Electromyography of rat soleus, medial gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior during hind limb suspension. Exp. Neurol. 1987;96:635–649. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell HJ, Haouzi P. The hypoxia-induced facilitation of augmented breaths is suppressed by the common effect of carbonic anhydrase inhibition. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2010;171:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blewett C, Elder GC. Quantitative EMG analysis in soleus and plantaris during hindlimb suspension and recovery. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;74:2057–2066. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.5.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolcskei K, Tekus V, Dezsi L, Szolcsanyi J, Petho G. Antinociceptive desensitizing actions of TRPV1 receptor agonists capsaicin, resiniferatoxin and N-oleoyldopamine as measured by determination of the noxious heat and cold thresholds in the rat. Eur. J. Pain. 2010;14:480–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang FC, Harper RM. A procedure for chronic recording of diaphragmatic electromyographic activity. Brain Res. Bull. 1989;22:561–563. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke IR, Brodecky V, Berger PJ. Easily-implantable electrodes for chronic recording of electromyogram activity in small fetuses. J. Neurosci. Methods. 1990;33:51–54. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90081-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow DE, Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. EMG-based detection of inspiration in the rat diaphragm muscle. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2006;1:1204–1207. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow DE, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC, Mantilla CB. Correlation of respiratory activity of contralateral diaphragm muscles for evaluation of recovery following hemiparesis. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2009;1:404–407. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5334892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge FL. Relationship between respiratory nerve and muscle activity and muscle force output. J. Appl. Physiol. 1975;39:567–574. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier M, Sieck GC. Somatotopy in the segmental innervation of the cat diaphragm. J. Appl. Physiol. 1988;64:291–298. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Sandhu MS, Doperalski NJ, Lane MA, White TE, Bishop MD, Reier PJ. Graded unilateral cervical spinal cord injury and respiratory motor recovery. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009;165:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Reier PJ, Bolser DC. Altered respiratory motor drive after spinal cord injury: supraspinal and bilateral effects of a unilateral lesion. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8680–8689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08680.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Seven YB, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. Diaphragm motor unit recruitment in rats. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2010;173:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Sieck GC. Mechanisms underlying motor unit plasticity in the respiratory system. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;94:1230–1241. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01120.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Sieck GC. Key aspects of phrenic motoneuron and diaphragm muscle development during the perinatal period. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:1818–1827. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01192.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Sieck GC. Neuromuscular adaptations to respiratory muscle inactivity. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009;169:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Liu C, Cao Y, Ling L. Formation and maintenance of ventilatory long-term facilitation require NMDA but not non-NMDA receptors in awake rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;105:942–950. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01274.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Zhang Y, White DP, Ling L. Effect of hypoxic episode number and severity on ventilatory long-term facilitation in awake rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002;93:2155–2161. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00405.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantwi KD, El-Bohy A, Schrimsher GW, Reier PJ, Goshgarian HG. Spontaneous functional recovery in a paralyzed hemidiaphragm following upper cervical spinal cord injury in adult rats. Neurorehab. Neural Repair. 1999;13:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Park MC, Belhaj-Saif A, Cheney PD. Chronic recording of EMG activity from large numbers of forelimb muscles in awake macaque monkeys. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2000;96:153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazka A, Westerman RA, Ziccone SP. Discharges of single hindlimb afferents in the freely moving cat. J. Neurophysiol. 1976;39:1090–1104. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.5.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoolman A, Fink BR. Permanently implanted electrode for electromyography of the diaphragm in the waking cat. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1963;15:127–128. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(63)90048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafford HL, Strittmatter RR, Schadt JC. A novel electrode design for chronic recording of electromyographic activity. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2006;156:228–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC. Neural control of the inspiratory pump. N.I.P.S. 1991;6:260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC. Physiological effects of diaphragm muscle denervation and disuse. Clin. Chest Med. 1994;15:641–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC, Fournier M. Diaphragm motor unit recruitment during ventilatory and nonventilatory behaviors. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989;66:2539–2545. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.6.2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC, Fournier M. Changes in diaphragm motor unit EMG during fatigue. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990;68:1917–1926. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.5.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieck GC, Mantilla CB. Role of neurotrophins in recovery of phrenic motor function following spinal cord injury. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009;169:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NC, Li A, Nattie EE. Medullary serotonergic neurones modulate the ventilatory response to hypercapnia, but not hypoxia in conscious rats. J. Physiol. 2005;566:543–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.083873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YD, Mocchetti I, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Gillis RA, Wrathall JR. Basic fibroblast growth factor increases long-term survival of spinal motor neurons and improves respiratory function after experimental spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7037–7047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-07037.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelease RB, Sieck GC, Harper RM. A new technique for acute and chronic recording of crural diaphragm EMG in cats. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1982;53:459–462. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(82)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SA, Annau Z, Senter G. Chronic recording of ECG and diaphragmatic EMG in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 1967;23:971–975. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]