Abstract

Background

Recognising patients who will die in the near future is important for adequate planning and provision of end-of-life care. GPs can play a key role in this.

Aim

To explore the following questions: How long before death do GPs recognise patients likely to die in the near future? Which patient, illness, and care-related characteristics are related to such recognition? How does recognising death in the near future, before the last week of life, relate to care in during this period?

Design and setting

One-year follow-back study via a surveillance GP network in the Netherlands.

Method

Registration of demographic and care-related characteristics.

Results

Of 252 non-sudden deaths, 70% occurred in the home or care home and 30% in hospital. GP recognition of death in the near future was absent in 30%, and occurred prior to the last month in 15%, within the last month in 19%, and in the last week in 34%. Logistic regression analyses showed cancer and low functional status were positively associated with death in the near future; cancer and discussing palliative care options were positively associated with recognising death in the near future before the last week of life. Recognising death in the near future before patients’ last week of life was associated with fewer hospital deaths, more GP–patient contacts in the last week, more deaths in a preferred place, and more-frequent GP–patient discussions about specific topics in the last 7 days of life.

Conclusion

Recognising death in the near future precedes several aspects of end-of-life care. The proportion in whom death in the near future is never recognised is large, suggesting GPs could be assisted in this process through training and implementation of care protocols that promote timely recognition of the dying phase.

Keywords: death, general practitioner, home care, primary care, recognition of dying phase, terminal care

INTRODUCTION

Due to ageing and multiple progressive illnesses, patients facing the end of life at home are growing in number.1 Regardless of disease, timely identification of these patients is vital in the planning and provision of appropriate end-of-life care.1,2 The complexity of using the dying phase in non-acute situations is such that it is often unclear when the end of life starts. Depending on the trajectory of non-sudden dying, there could be a short period of evident decline (cancer), a period of long-term limitations with intermittent crises (organ failure), or a period of steady decline (frailty). By and large, patient needs differ depending on which of these trajectories they encounter.3

GPs can play an important role in identifying when patients will die. They are involved in home visits, treatment provision, treatment choices, and end-of-life decisions concerning the place and type of care. Realising that a patient will die in the near future has important repercussions for the care given, such as the control of aggressive diagnostic interventions, acceleration of comfort care, and alignment of care with patient wishes.4 Given the increasing incidence of cancer, congestive heart failure, dementia, and other life-limiting conditions in general practice,5–7 GP care at the end of life is pivotal,8,9 particularly for patients who choose to die at home,7–9 and many do.10 Timely awareness of death in the near future has been associated with fewer hospitalisations, more palliative care referrals, and better bereavement adjustment.11,12 However, not much is known about GPs recognising the final phase in patients who die at home,13 especially among those with non-malignant diseases.14 The ability to identify patients in the final phase of life, according to Andersen’s behavioural model on access to medical care, is a behavioural trait or practice which could be learned.8,15 Also, previous literature suggests certain characteristics may influence recognition of patients’ death in the near future.16,17 However, related studies have been limited to specific settings,16,18,19 diagnoses,16,20,21 age groups,17,21 and functional states.17,22 To the best of this study’s knowledge, this is the first nationwide study that examines the timing of and the factors associated with recognising death in the near future from a general patient population.

How this fits in

GPs can play an important role in the timely recognition of patients who will die soon, but nationwide research exploring how often they do so is scarce. The results of this study show that cancer is still the main reason for recognising death in the near future, and recognising death in the near future precedes several aspects of end-of-life care. The relatively large number of patients for whom death in the near future is never recognised suggests that GPs can be assisted in this process by training or by implementing care protocols that promote timely recognition of the dying phase.

In this paper, the timing and extent of recognising death in the near future and its correlates are explored in those who died non-suddenly or unexpectedly, using a nationwide representative surveillance network of GPs. The following three research questions are addressed:

How long before death do GPs recognise patients likely to die in the near future?

Which patient, illness, and care-related characteristics are related to such recognition?

How does recognising death in the near future, before the last week of life, relate to care in during this period?

METHOD

Selection and procedure

Between 1 January and 31 December 2008, data of patients were collected in a sentinel network of GPs, an epidemiological surveillance system that is representative by age, sex, geographic distribution, and population density of all GPs practising in the Netherlands.23,24 The network covers close to 1% of the entire registered patient population. On average, it comprises 65–70 GPs who work singly or in groups, within 45 practices nationwide. The current study is part of a series of studies beginning in 2005 as a nationwide mortality follow-back study.25,26 In 2008, a structured registration form was sent to all sentinel GPs, requesting them to provide information on all deceased patients aged 1 year or older in relation to the care they received in the last 3 months of life. Of the 405 registered deaths, 129 ‘sudden and totally unexpected’ patients were excluded, as well as six who had spent most of their last year outside home or care home, one with >70% values missing, and 17 who died in a Dutch nursing home. In the Netherlands, GPs manage primary care for those at home and in residential care facilities, but hand over care once the patient is moved to a Dutch nursing home.

Data collection

The data-collection process was performed by NIVEL (the Netherlands Institute of Health Services Research), using a standardised protocol.24 Completed forms were sent by each sentinel GP to NIVEL, where the forms were scrutinised closely for errors and missing data. When possible, missing data were retrieved by telephone contact. Next, the forms were sent to the researchers for data entry and analyses. Because the registration forms were not uniquely identifiable, the researchers had access to neither the patients’ nor the GPs’ identities. More details on this methodology have been published elsewhere.26

Research instrument

The 21-question registration form consisted of multiple-choice and open-response questions designed to assess demographics, cause of death, and the following patient and end-of-life care characteristics: involvement of a multidisciplinary palliative care team; number of hospital and/or intensive care unit (ICU) admissions in the last 3 months of life; GP home visits and personal contact (excluding telephone calls) made in the last 3 months, last 2–4 weeks, and within the last week of life; GP home visits to family members and relatives after the bereavement; presence of dementia and/or coma in the last week of life; symptom frequency and distress in the last week of life using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale;27 functional state in the last week of life using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status;28 the GP’s awareness about the patient’s preferred place of death and/or other specific wishes; GP–patient communication about diagnosis, prognosis, incurability of illness, and treatment options; and the timing of the GP recognising death in the near future. The forms were tested rigorously for comprehensibility, and pilot tested among GPs in order to ensure that the participating GPs understood the items as intended.1 The main question, ‘How long before this patient’s death did you recognise that the patient would die in the near future?’, was assessed as ‘never recognised’, versus ‘recognised in the last week’, ‘the last 2–4 weeks’, ‘the last 2–3 months’, and ‘before the last 3 months’.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were done using SPSS (version 15.0). Descriptive statistics on relevant variables were derived. To analyse which patient and care characteristics are related to recognition of death in the near future, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed. This was done looking at ever versus never having recognised death in the near future (Table 1), and for recognising death in the near future before the patient’s last week of life versus in the last week of life or never (Table 2). For this last analysis, care characteristics that occurred before the last week of life were chosen as independent variables: admitted in hospital in the last month of life, palliative care initialisation before the last week of life, and the GP discussing several end-of-life issues before the last week of life.

Table 1.

Characteristics associated with recognising/not recognising death in the near future in patients who died non-suddenly at home/in a care home, n = 252a

| Logistic regressionb (odds ratio [95%CI]) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient and care characteristics | Total % | Did not recognise death in the near future (n = 72),% | Recognised death in the near future (n = 175),% | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analysesc |

| Age, years | |||||

| 1–64 | 20 | 18 | 21 | 1 | |

| 65–85 | 41 | 42 | 40 | 0.84 (0.4 to 1.8) | d |

| ≥85 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 0.86 (0.4 to 1.9) | d |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 45 | 53 | 42 | 1 | |

| Female | 55 | 47 | 58 | 1.53 (0.9 to 2.6) | d |

| Education | |||||

| Elementary | 48 | 59 | 44 | 1 | |

| Secondary | 39 | 31 | 41 | 1.77 (0.9 to 2.6) | d |

| Tertiary | 13 | 9 | 14 | 2.02 (0.8 to 5.4) | d |

| Dutch nationality | |||||

| ≥1 parent | 94 | 96 | 93 | 1 | |

| ≤1 parent | 6 | 4 | 7 | 1.58 (0.4 to 5.8) | d |

| Cause of death | |||||

| Cancer | 38 | 15 | 47 | 1 | 1 |

| Not cancer | 62 | 85 | 53 | 0.20 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.18 (0.1 to 0.4) |

| Dementia diagnosed by a physician | |||||

| No | 88 | 88 | 88 | 1 | |

| Yes | 12 | 12 | 12 | 0.95 (0.4 to 2.3) | d |

| Related symptoms and functional state before death | |||||

| Comatose | |||||

| No | 48 | 59 | 48 | 1 | |

| Yes | 52 | 41 | 52 | 0.64 (0.3 to 1.2) | d |

| Lack of appetite | |||||

| No | 22 | 46 | 17 | 1 | |

| Yes | 78 | 54 | 83 | 4.10 (1.9 to 8.8) | d |

| Lack of energy | |||||

| No | 8 | 18 | 6 | 1 | |

| Yes | 92 | 82 | 94 | 3.68 (1.3 to 10.6) | d |

| Pain | |||||

| No | 52 | 58 | 50 | 1 | |

| Yes | 48 | 42 | 50 | 1.39 (0.7 to 2.8) | d |

| Difficulty breathing | |||||

| No | 59 | 66 | 57 | 1 | |

| Yes | 41 | 34 | 43 | 1.45 (0.7 to 3.0) | d |

| Anxiety | |||||

| No | 60 | 58 | 60 | 1 | |

| Yes | 40 | 42 | 40 | 0.94 (0.4 to 2.0) | d |

| Low functional status capable of only limited self-care (ECOG score ≥4)e | |||||

| No | 85 | 32 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 15 | 68 | 92 | 5.39 (2.5 to 11.5) | 5.21 (2.3 to 11.7) |

ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Includes five missing values; percentages of missing observations variables ranged between 0.4% and 5.6%.

Dependent variable: patients in whom GPs ever recognised death in the near future, n = 175; reference group: patients who died without their GPs recognising death in the near future, n = 72.

Stepwise backwards logistic regression. Variables removed after three steps of the backward analyses. Significant values are in bold.

Not entered/retained following multiple backwards logistic regression analyses.

ECOG scale.29

Table 2.

Characteristics associated with recognising/not recognising death in the near future before the last week of life in patients who died non-suddenly at home/in a care home, n = 252a

| Logistic regressionb odds ratio (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient and care characteristics | Total % | Did not recognise death in the near future (n = 154), % | Recognised death in the near future (n = 93), % | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analysesc |

| Age, years | |||||

| 1–64 | 20 | 18 | 24 | 1 | |

| 65–85 | 41 | 37 | 47 | 0.93 (0.5 to 1.8) | d |

| ≥85 | 39 | 45 | 29 | 0.46 (0.2 to 0.9) | d |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 45 | 44 | 47 | 1 | |

| Female | 55 | 56 | 53 | 0.88 (0.5 to 1.5) | d |

| Education | 48 | 53 | 42 | 1 | |

| Elementary | |||||

| Secondary | 39 | 36 | 43 | 1.50 (0.8 to 2.7) | d |

| Tertiary | 13 | 11 | 16 | 1.80 (0.8 to 4.1) | d |

| Dutch nationality | |||||

| ≥1 parent | 94 | 96 | 90 | 1 | |

| ≤1 parent | 6 | 4 | 10 | 2.58 (0.9 to 7.5) | d |

| Primary cause of death | |||||

| Cancer | 38 | 25 | 59 | 1 | 1 |

| Not cancer | 62 | 75 | 41 | 0.23 (0.1 to 0.4) | 0.29 (0.2 to 0.5) |

| Dementia diagnosed by a physician | |||||

| No | 88 | 85 | 93 | 1 | |

| Yes | 12 | 15 | 7 | 0.38 (0.2 to 1.0) | |

| Admitted to hospital and/or ICU in the last 30 days of life | |||||

| No | 55 | 55 | 55 | 1 | |

| Yes | 45 | 45 | 45 | 0.99 (0.6 to 1.7) | d |

| Palliative care initialisation (before the last week of life) | |||||

| No | 75 | 65 | 85 | 1 | |

| Yes | 25 | 35 | 15 | 0.32 (0.1 to 1.0) | d |

| GP–patient communication prior to the last week of life | |||||

| GP discussed the diagnosis | |||||

| No | 48 | 55 | 38 | 1 | |

| Yes | 52 | 45 | 62 | 1.93 (1.1 to 3.3) | d |

| GP discussed the prognosis | |||||

| No | 44 | 53 | 30 | 1 | |

| Yes | 56 | 47 | 70 | 2.68 (1.5 to 4.7) | d |

| GP discussed the incurability | |||||

| No | 44 | 53 | 30 | 1 | |

| Yes | 56 | 47 | 70 | 2.68 (1.5 to 4.7) | d |

| GP discussed palliative care options | |||||

| No | 55 | 67 | 35 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 45 | 33 | 65 | 3.73 (2.1 to 6.5) | 2.37 (1.3 to 4.4) |

ICU = intensive care unit.

Includes five missing values; percentages of missing observations variables ranged between 0.4% and 5.6%.

Dependent variable: patients in whom GPs recognised death in the near future before the last week of life n = 93, reference group: patients in whom GPs did not recognise death in the near future before or in the last week of life n = 154

Stepwise backwards logistic regression. Variables removed after three steps of the backward analyses. Significant values are in bold.

Not entered/retained following multiple backwards logistic regression analyses.

To analyse which care characteristics taking place after recognising death in the near future were related to this recognition, logistic regression analyses were performed with recognising death in the near future as the independent variable (Table 3; never versus ever recognised). Dependent variables were care characteristics that concerned the last week of life. Patients for whom death in the near future was recognised in their last week of life were omitted from this analysis, to ensure that in the analysis the recognition took place before the care characteristic. These analyses were controlled for the two patient characteristics that were found to be related to recognising death in the near future: cancer and the patient’s functional state (Table 1).

Table 3.

Relationship between recognising death in the near future before the last week of life and care characteristics in the last week of life, (n = 165)a

| Never recognised death in the near future before patient died (n = 72),% | Recognised death in the near future before patient's last week (n = 93),% | Odds ratio (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of death: hospital | |||

| No | 24 | 76 | 0.15 (0.06 to 0.4) |

| Yes | 77 | 23 | |

| Total | 44 | 56 | |

| Initiation of palliative care services in the last week | |||

| No | 37 | 63 | 6.7 (0.6 to 73.1) |

| Yes | 9 | 91 | |

| Total | 15 | 85 | |

| Number of GP–patient contacts in the last week of life (2 or median) | |||

| No | 65 | 35 | 11.5 (4.2 to 31.0) |

| Yes | 9 | 91 | |

| Total | 42 | 58 | |

| Dying in a preferred place | |||

| No | 54 | 46 | 4.38 (1.4 to 14) |

| Yes | 21 | 79 | |

| Total | 28 | 72 | |

| GP–patient communication on specific end-of-life issues in the last week of life | |||

| Possible complications | |||

| No | 49 | 51 | 3.08 (1.1 to 8.5) |

| Yes | 22 | 78 | |

| Total | 43 | 57 | |

| Physical complaints | |||

| No | 57 | 41 | 4.39 (1.9 to 10.3) |

| Yes | 23 | 77 | |

| Total | 43 | 57 | |

| Psychological problems | |||

| No | 50 | 50 | 2.55 (1.0 to 6.4) |

| Yes | 24 | 76 | |

| Total | 42 | 57 | |

| Social problems | |||

| No | 50 | 50 | 2.07 (0.8 to 5.5) |

| Yes | 25 | 75 | |

| Total | 43 | 57 | |

| Spiritual/existential problems | |||

| No | 46 | 54 | 4.5 (0.5 to 41.3) |

| Yes | 9 | 91 | |

| Total | 43 | 57 | |

| Palliative care options | |||

| No | 53 | 47 | 4.92 (1.6 to 14.7) |

| Yes | 12 | 88 | |

| Total | 42 | 58 | |

| Treatment burdens | |||

| No | 47 | 53 | 1.81 (0.6 to 5.1) |

| Yes | 23 | 77 | |

| Total | 43 | 57 | |

Excluding 82 in whom death in the near future was recognised within the last week of life and five missing values. Percentages of missing observations variables ranged between 0.4% and 5.6%.

Corrected for cancer diagnosis and ambulant functional state. Significant levels in bold.

RESULTS

Incidence and timing of recognising patients with likely death in the near future

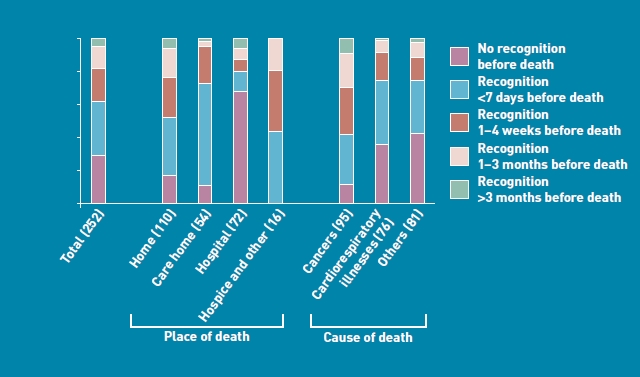

A total of 252 patients were studied who had died non-suddenly in 2008. Excluding the 16 patients who had died elsewhere, 70% of the registered deaths took place at home or in a care home, while 30% occurred in a hospital or acute setting. Death in the near future was never recognised by a GP in 30% cases, in less than one-fifth of home and care-home deaths, and in about two-thirds of hospital deaths. Death was recognised before the last month, within the last month, and in the last week of life, in 15% 19%, and 34% respectively. Before or within the last month, death in the near future was recognised more among patients who died at home (23%), compared to those who died in both care homes and hospitals (6%). In the last 4 weeks, death in the near future was recognised more among patients at home (24%) and in a care home (23%), than among patients in hospital (8%). Across all the care settings, death in the near future was recognised most frequently in the last week of life. Altogether, death in the near future was never recognised three times as often among patients with cardiorespiratory (36%) and other (43%) illnesses, compared to cancer (12%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Recognition of death in the near future in patients who died non-suddenly, by place and cause of death, n = 252 (includes 5 missing values; percentages of missing observations variables ranged between 0.4% and 5.6%).

Characteristics associated with recognising death in the near future

Of the variables explored, age, sex, education, ethnicity, level of consciousness, and mental state did not appear to be associated with recognising death in the near future. On univariate analyses, recognising death in the near future was positively associated with a diagnosis of cancer, lack of appetite, lack of energy, and limited functional status. Multivariately, recognising death in the near future was positively associated with a diagnosis of cancer and low functional status (Table 1).

Characteristics associated with recognising death in the near future before the last week of life

Age, diagnosis of cancer, and discussing ‘diagnosis’, ‘prognosis’, ‘incurability’, and ‘palliative care options’ with the patient before the last weeks of life were associated positively with recognising death in the near future before the very last week of life — univariately. Multivariately, cancer death and discussing palliative care options maintained a positive relationship with recognising death in the near future before the last week of life (Table 2). Similar results were obtained when the analyses were repeated for the period up to 1 month before death (not shown).

Care characteristics that are related to recognition of death in the near future

On correcting for cancer and functional status, recognising death in the near future up to at least 1 week before patient’s death was related to fewer hospital deaths, more GP–patient contacts in the last week of life, more deaths in a preferred place, and more frequent GP–patient discussions about ‘possible complications’, ‘physical complaints’, ‘psychological problems’, and ‘palliative care options’ in the last 7 days of life (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Summary

GPs did not recognise death in the near future in about one-third of the non-sudden deaths, and one-third of the patients who died at home (Figure 1). Patients who died in hospital (versus elsewhere) had the largest proportion of non-recognition. ‘Last week’ recognition of death in the near future was commonest in care-home deaths. Recognition of death in the near future was strongly associated with dying from cancer (versus other diagnoses), and having limited functional state. Recognising death in the near future before the last week of life was associated with cancer, younger age (<85 years), and the GP discussing diagnosis, prognosis, incurability, and palliative care options with patient. Care characteristics in the last week of life related to recognising death in the near future before the patient’s last week were: fewer hospital deaths, more GP–patient contacts, more deaths in a preferred place, and more frequent GP–patient discussions about ‘possible complications’, ‘physical complaints’, ‘psychological problems’, and ‘palliative care options’ (Table 3).

Strengths and limitations

To the best of this authors’ knowledge, this is the first nationwide population-based study that has examined GP recognition of death in the near future in patients whose deaths were non-sudden. To produce reliable results, nationally representative GPs were enlisted from an existing surveillance network with a data-collection and quality-assurance protocol, to minimise incomplete data and GP recall bias. The study selected a general patient population, all of whom, in principle, could benefit from planned terminal care. The independent variables were selected in such a way that they preceded the dependent variables, in terms of timing. A retrospective collection was advantageous because all the deaths were captured upfront, unlike in prospective studies where patients are sought based on diagnosis (cancer) or certain characteristics (pain, breathlessness), and drop-out rates are often high.13 Although the ‘expected’ and ‘non-sudden’ categorisations may have been better understood in retrospect, this limitation is a reality of clinical practice. However, it is possible that some GPs provided socially desirable responses, given the self-reporting nature of the study. Altogether, the exclusion of Dutch nursing home residents from this study calls for some caution in interpretation and generalisation of the results.

Comparison with existing literature

Murray et al demonstrated palliative care needs accompanying the three main illness trajectories.3,20 Patients at home are increasingly dying from a combination of these illness trajectories. McKinley et al highlighted the need for GPs to be able to identify the terminal phase of diseases during their care of patients with non-malignant diseases, that is, organ failure (acute deterioration and recovery) and frailty (prolonged decline), based on the notion that such patients received less care, perhaps due to non-recognition of their terminal status.14 The present results, like McKinley’s,14 show that death in the near future was (five times) less recognised in patients with non-cancer versus cancer. However, the present data associate recognising death in the near future with fewer hospital deaths; it is possible the GPs did not recognise death in the near future in many of the hospitalised patients because they ceased to be involved in their care following admission. In Belgium, Van den Block et al reported the institutionalised nature of dying, even among GP-managed patients with ‘palliative care’ treatment goals.30

Death in the near future was recognised earlier (before the last month) in patients at home than those in a care homes, and last week recognition was more common in care-home than home residents. Regardless of disease, non-recognition of death in the near future was more common in patients who died in a non-preferred place, experienced less GP contact, and were less informed about their illness and other related end-of-life issues, than similar patients in whom death in the near future was recognised at least 1 week prior to death. It could be argued that an earlier recognition would be even more desirable in conditions like heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that have no curative treatment, and dementia, which lacks an accurate scale for such recognition.

The results of the present study show recognition of death in the near future in the last 7 days to be associated with having cancer, having a low functional status (ECOG ≥4), older age (>85 years), and the presence of communication about end-of-life issues in or by the last 2–4 weeks of life. From research, it is known that patients with chronic cardiorespiratory illnesses have unmet communication needs,31 and it is possible that if their GPs were able to recognise death in the near future, they may be able to better manage communication and care.

Implications for research and practice

Recognising death in the near future is vital for planning end-of-life care, decision making, and allocation of resources. The results of this study show this, and it may actually pre-empt the initiation of end-of-life discussions. Across settings, death in the near future was completely missed in almost 20% of all home deaths, and 80% of all hospital deaths (Figure 1). While it should be acknowledged that the dying phase will not always be discernible, these results point to the fact that GPs may utilise salient triggers in the process of recognition, that is, by assessing palliative care needs more systematically.20 Systematic assessment of needs can be aided by interventions such as the Gold Standards Framework (GSF), which is a generic improvement tool, initially used for cancer patients, but currently developed for any patient with a life-limiting illness, living in any setting. Unlike the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying (LCP), which addresses only the last days of life, the GSF extends to a considerably longer period before death,27 and is used increasingly alongside the LCP.32

Acknowledgments

We thank all the sentinel GPs in The Netherlands for participating in this study and for supplying all the data used; also, Marianne Heshusius of The Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL) for supervising the collection process; and Piet Kostense of the EMGO+ Institute, for his statistical advice.

Funding body

This study is part of the Monitoring End-of-Life Care through the Sentinel network of GPs (SENTI-MELC) study — a collaboration between VU Brussels, University of Ghent, University of Antwerp, the Belgian Scientific Institute of Public Health, the Netherlands Institute of Health Services Research, and VU Medical Centre Amsterdam. It was supported financially by the Belgian Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (grant no. SBO IWT 050158), as a strategic and comparative research project. The sponsors played no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analyses, or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript. The corresponding author, together with the co-authors, had full access to all the data used, and have the final responsibility for the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Ethical approval

An ethical review was not required by the Dutch law, since data were collected after the death of patients. However, the study complied with the protocol and anonymity procedures of the Netherlands Institute of Health Services Research, and more details on this are published elsewhere.25

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Palliative care: the solid facts. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/palliative.pdf (accessed 4 May 2011) [PubMed]

- 3.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ. 2005;330(7498):1007–1011. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, et al. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer RP. Consider medical care at home. Geriatrics. 2009;64(6):9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson KM, Reinhard SC. Looking ahead in long-term care: the next 50 years. Nurs Clin North Am. 2009;44(2):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsasis P. Chronic disease management and the home-care alternative in Ontario, Canada. Health Serv Manage Res. 2009;22(3):136–139. doi: 10.1258/hsmr.2009.009002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schers H, Webster S, van den HH, et al. Continuity of care in general practice: a survey of patients’ views. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(479):459–462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stokes T, Tarrant C, Mainous AG, III, et al. Continuity of care: is the personal doctor still important? A survey of general practitioners and family physicians in England and Wales, the United States, and The Netherlands. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):353–359. doi: 10.1370/afm.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gruneir A, Mor V, Weitzen S, et al. Where people die: a multilevel approach to understanding influences on site of death in America. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(4):351–378. doi: 10.1177/1077558707301810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welch LC, Miller SC, Martin EW, Nanda A. Referral and timing of referral to hospice care in nursing homes: the significant role of staff members. Gerontologist. 2008;48(4):477–484. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson DC, Kutner JS, Armstrong JD. Would you be surprised if this patient died?: preliminary exploration of first and second year residents’ approach to care decisions in critically ill patients. BMC Palliat Care. 2003;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKinley RK, Stokes T, Exley C, Field D. Care of people dying with malignant and cardiorespiratory disease in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(509):909–913. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamel MB, Goldman L, Teno J, et al. Identification of comatose patients at high risk for death or severe disability. SUPPORT Investigators. Understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. JAMA. 1995;273(23):1842–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostertag SG, Forman WB. End-of-life care in Hancock County, Maine: a community snapshot. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(2):132–138. doi: 10.1177/1049909107310143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veerbeek L, van ZL, Swart SJ, et al. The last 3 days of life in three different care settings in The Netherlands. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(10):1117–1123. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murtagh FE, Preston M, Higginson I. Patterns of dying: palliative care for non-malignant disease. Clin Med. 2004;4(1):39–44. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.4-1-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes S, Gott M, Payne S, et al. Predicting mortality among a general practice-based sample of older people with heart failure. Chronic Illn. 2008;4(1):5–12. doi: 10.1177/1742395307083783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellershaw J, Smith C, Overill S, et al. Care of the dying: setting standards for symptom control in the last 48 hours of life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21(1):12–17. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Alphen JE, Donker GA, Marquet RL. Requests for euthanasia in general practice before and after implementation of the Dutch Euthanasia Act. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(573):263–267. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donker GA. Utrecht: NIVEL; 2008. Continuous morbidity registration at Dutch sentinel stations 2007. http://www.nivel.nl/pdf/Rapport-CMR-Engels-jaarverslag%202007.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abarshi E, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Donker G, et al. General practitioner awareness of preferred place of death and correlates of dying in a preferred place: a nationwide mortality follow-back study in the Netherlands. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(4):568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van den Block L, Van Casteren V, Deschepper R, et al. Nationwide monitoring of end-of-life care via the Sentinel Network of General Practitioners in Belgium: the research protocol of the SENTI-MELC study. BMC Palliat Care. 2007;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The Gold Standards Framework. GSF in primary care. http://www.goldstandardsframework.nhs.uk/GSFInPrimary+Care (accessed 23 Mar 2011)

- 28.Cartwright C, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Williams G, et al. Physician discussions with terminally ill patients: a cross-national comparison. Palliat Med. 2007;21(4):295–303. doi: 10.1177/0269216307079063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van den Block L, Deschepper R, Drieskens K, et al. Hospitalisations at the end of life: using a sentinel surveillance network to study hospital use and associated patient, disease and healthcare factors. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harding R, Selman L, Beynon T, et al. Meeting the communication and information needs of chronic heart failure patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hockley J, Watson J, Oxenham D, Murray SA. The integrated implementation of two end-of-life care tools in nursing homes in the UK: an in-depth evaluation. Palliat Med. 2010;24(8):828–838. doi: 10.1177/0269216310373162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]