Abstract

Obesity may increase the risk for progression of CKD, but the effect of established renoprotective treatments in overweight and obese patients with CKD is unknown. In this post hoc analysis of the Ramipril Efficacy In Nephropathy (REIN) trial, we evaluated whether being overweight or obese influences the incidence rate of renal events and affects the response to ramipril. Of the 337 trial participants with known body mass index (BMI), 105 (31.1%) were overweight and 49 (14.5%) were obese. Among placebo-treated patients, the incidence rate of ESRD was substantially higher in obese patients than overweight patients (24 versus 11 events/100 person-years) or than those with normal BMI (10 events/100 person-years); we observed a similar pattern for the combined endpoint of ESRD or doubling of serum creatinine. Ramipril reduced the rate of renal events in all BMI strata, but the effect was higher among the obese (incidence rate reduction of 86% for ESRD and 79% for the combined endpoint) than the overweight (incidence rate reduction of 45 and 48%, respectively) or those with normal BMI (incidence rate reduction of 42 and 45%, respectively). We confirmed this interaction between BMI and the efficacy of ramipril in analyses that adjusted for potential confounders, and we observed a similar effect modification for 24-hour protein excretion. In summary, obesity predicts a higher incidence of renal events, but treatment with ramipril can essentially abolish this risk excess. Furthermore, the reduction in risk conferred by ramipril is larger among obese than nonobese patients.

Excessive body fat is the most concerning risk factor for chronic diseases worldwide. Overweight and obesity are consistently associated with a variety of cardiovascular sequelae ranging from angina and myocardial infarction to peripheral vascular disease and with various types cancer.1 Evidence has emerged that obesity is also implicated in the high prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Japan,2,3 the United States,4 and Sweden.5 Analyses based on the Atherosclerosis Risk in the Community study and Cardiovascular Health Study have shown that metrics of central obesity are monotonically associated with the risk of CKD and death.6 Traditional and nontraditional risk factors such as inflammation, deranged adipose tissue cytokines, enhanced sympathetic activity, and activation of the renin-aldosterone system are considered as the major factors implicated in CKD secondary to excess adiposity.6 Overweight and obesity impose peculiar renal hemodynamic, hormonal, and metabolic risk factors to the kidney,7 and these alterations set apart renal damage associated with body fat excess from that in other nephropathies.

Preventing and treating renal disease secondary to excessive body fat is now a public health priority.8 However, there is still little information on the reversibility of obesity-related nephropathy and virtually no information on the response of this nephropathy to drug treatment with agents proved to be nephroprotective in other primary or secondary renal diseases.9 Because of the peculiar patho-physiologic profile of overweight and obesity, the effect of drugs in other progressive nephropathies may not apply to fat excess–related nephropathy. Therefore, specific studies are needed to test interventions aimed at retarding CKD progression in patients with body fat excess.

With this background in mind, we undertook a secondary analysis in the Ramipril Efficacy In Nephropathy (REIN) study cohort,10 i.e., the cohort of patients that was the basis of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial testing the nephroprotective properties of ramipril, to see whether overweight and obesity influence the incidence rate of renal events and modify the response to this angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor.

RESULTS

CKD patients included in this secondary analysis (n = 337) did not differ from the original study cohort (n = 352) regarding demographic, clinical, and biochemical data (data not shown). One hundred sixty-eight patients were treated with ramipril and 169 patients were treated with placebo. One hundred five patients were overweight (body mass index [BMI] ranging from 25 to 30 kg/m2) and 49 were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2). GFR was on average 43 ± 18 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (range, 14 to 101 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Twenty-four-hour urinary protein was ≤3.0 g/24 h in 178 patients and was >3.0 g/24 h in the remaining 159 patients. Descriptive data according to BMI categories (<25, 25 to 30, and >30 kg/m2) and study arms (ramipril/placebo) showed that, at baseline, among patients with BMI <25 kg/m2 randomized to ramipril, there was a higher proportion of men and a lower proportion of smokers and these patients had slightly lower hemoglobin compared with patients on placebo (Table 1). In overweight patients (BMI ranging from 25 to 30 kgm2), GFR was 6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 higher in ramipril-treated patients than in placebo-treated patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main clinical and biochemical characteristics of study population according to study arms and BMI categories

| BMI <25 kg/m2 |

P | BMI = 25 to 30 kg/m2 |

P | BMI >30 kg/m2 |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramipril (n = 92) | Placebo (n = 91) | Ramipril (n = 50) | Placebo (n = 55) | Ramipril (n = 27) | Placebo (n = 22) | ||||

| Age (years) | 45 ± 14 | 46 ± 14 | 0.89 | 53 ± 10 | 52 ± 13 | 0.99 | 54 ± 12 | 58 ± 11 | 0.26 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 74 (80%) | 61 (67%) | 0.04 | 44 (88%) | 44 (80%) | 0.27 | 17 (63%) | 17 (77%) | 0.28 |

| Smokers, n (%) | 14 (15%) | 25 (27%) | 0.05 | 7 (13%) | 7 (14%) | 0.85 | 3 (14%) | 5 (19%) | 0.65 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 0.72 | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 0.14 | 7 (26%) | 4 (18%) | 0.52 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 236 ± 76 | 245 ± 56 | 0.38 | 244 ± 61 | 236 ± 54 | 0.51 | 260 ± 62 | 264 ± 57 | 0.80 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 0.48 | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.12 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 0.68 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 98 ± 20 | 101 ± 36 | 0.41 | 105 ± 45 | 106 ± 38 | 0.90 | 140 ± 48 | 120 ± 42 | 0.12 |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 9.1 ± 1.2 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 0.33 | 9.3 ± 0.5 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 0.35 | 9.2 ± 1.4 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 0.45 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 13.6 ± 2.0 | 13.1 ± 1.8 | 0.06 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 13.5 ± 1.8 | 0.26 | 13.5 ± 1.4 | 13.9 ± 1.8 | 0.36 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 143 ± 19 | 145 ± 18 | 0.40 | 147 ± 18 | 145 ± 17 | 0.60 | 151 ± 17 | 152 ± 16 | 0.88 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 89 ± 13 | 90 ± 12 | 0.70 | 92 ± 10 | 90 ± 10 | 0.23 | 88 ± 10 | 92 ± 14 | 0.30 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 107 ± 13 | 108 ± 12 | 0.52 | 110 ± 12 | 108 ± 11 | 0.33 | 109 ± 10 | 112 ± 14 | 0.44 |

| Urinary protein (g/24 h) | 2.6 (1.5 to 3.8) | 3.1 (1.6 to 4.3) | 0.18 | 3.1 (1.5 to 5.6) | 2.7 (1.5 to 3.7) | 0.20 | 3.4 (1.5 to 5.3) | 3.4 (2.3 to 6.6) | 0.32 |

| GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 43 ± 19 | 42 ± 18 | 0.57 | 46 ± 17 | 40 ± 16 | 0.05 | 50 ± 24 | 41 ± 18 | 0.18 |

Data are expressed mean ± SD or as percent frequency, as appropriate.

Univariate Correlates of Renal Events in Ramipril- and Placebo-Treated Patients

During the follow-up period (average, 30 months; range, 0.2 to 76 months), 89 patients experienced renal events (ESRD in 77 cases and doubling of serum creatinine in the remaining 12 cases) and 4 patients died. Because ACE inhibition reduced renal events in the REIN study,10 time to event analysis was carried out separately in the two study arms. On univariate Cox regression analyses, in both ramipril- and placebo-treated patients, 24-hour urinary protein (P < 0.001) and systolic arterial BP (P ≤ 0.015) were direct predictors of the incidence rate of ESRD, whereas hemoglobin (P < 0.001), GFR (P < 0.001), and serum albumin (P ≤ 0.06) were inverse predictors of the same outcome. Similar relationships were also found for the combined renal endpoint of ESRD and doubling of serum creatinine (data not shown). In neither study arm was a significant relationship found between the incidence rate of renal events and the remaining risk factors listed in Table 1 (P = not significant).

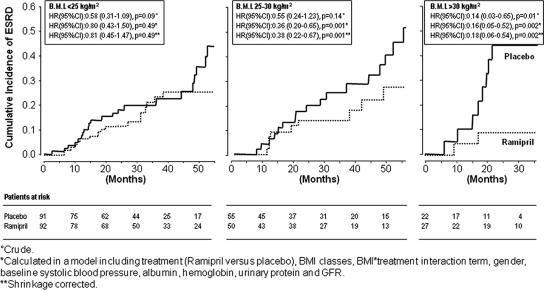

BMI and Renal Events: Effect Modification of Overweight and Obesity on the Response to Ramipril

In placebo-treated patients, the incidence rate of ESRD was similar in patients with normal BMI and in those who were overweight but was substantially higher in those with BMI >30 kg/m2 (Table 2). Ramipril treatment reduced the rate of ESRD compared with placebo in all BMI strata (Table 2), but the effect of this drug was much higher in obese patients (incidence rate reduction: −86%) than in those with overweight (incidence rate reduction: −45%) or normal BMI (incidence rate reduction: −42%). The effect modification of BMI on the efficacy of ramipril for the incidence rate of ESRD was confirmed in a multivariate Cox regression model (Table 3; Figure 1) adjusting for the main effect of BMI and ramipril treatment, as well as for systolic arterial BP and other potential confounders did not materially affect these results (Table 3). The same (effect modification) analyses carried out for the incidence rate of the combined renal endpoint (ESRD and doubling of serum creatinine) showed very similar results (Table 2); the effect of ramipril was higher in obese patients (incidence rate reduction: −79%) than in those with overweight (incidence rate reduction: −48%) or normal BMI (incidence rate reduction: −45%). Forcing other variables into the Cox's model that did not meet standard criteria to be confounders and predictive factors (age, smoking, and diabetes) did not change the strength of these relationships. A Cox regression analysis taking into account the competing risk of death provided identical results (data not shown). An effect modification analysis with BMI as the continuous variable will be provided to interested readers on request. Consistent findings were obtained when BMI was considered as a continuous variable (Supplemental Appendix 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rate of ESRD and combined renal endpoint and according to BMI categories and study arms (ramipril versus placebo)

| Crude Incidence Rate of ESRD Occurrence (Events/100 Person-Years) |

Crude Hazard Ratio and 95% CI and P Value (Ramipril versus Placebo) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo group | Ramipril group | ||

| Incidence rate of ESRD | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 10 (7 to 16) | 6 (4 to 10) | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.09), P = 0.09 |

| 25 to 30 kg/m2 | 11 (7 to 8) | 6 (3 to 12) | 0.55 (0.24 to 1.23), P = 0.14 |

| >30 kg/m2 | 24 (11 to 45) | 3 (0.4 to 11) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.65), P = 0.01 |

| Incidence rate of the combined renal endpoint (ESRD and doubling of serum creatinine) | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 14 (9 to 20) | 8 (5 to 11) | 0.55 (0.31 to 0.99), P < 0.05 |

| 25 to 30 kg/m2 | 14 (8 to 21) | 7 (3 to 13) | 0.52 (0.24 to 1.13), P = 0.09 |

| >30 kg/m2 | 25 (11 to 41) | 5 (1 to 14) | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.81), P = 0.02 |

Data are incidence rate and 95% confidence intervals. The hazard ratio of ramipril treatment compared with placebo in each BMI stratum is reported in the last column.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis of the primary end point (ESRD occurrence)

| Hazard Ratio, 95% CI, and P Value | ||

|---|---|---|

| BMI × ramipril treatment interaction term (adjusted for the main effect of BMI and ramipril treatment) | See in box in Fig. 1 (P for interaction = 0.03) | See in box in Fig. 1 (P for interaction = 0.04) |

| Systolic BP (1 mmHg) | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03), P = 0.004 | 1.02 (1.01 to 1.03), P = 0.007 |

| Albumin (1 g/dl) | 0.47 (0.30 to 0.74), P = 0.001 | 0.49 (0.31 to 0.78), P = 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin (1 g/dl) | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.97), P = 0.01 | 0.86 (0.75 to 0.98), P = 0.02 |

| Urinary protein (1 g/24 h) | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.30), P < 0.001 | 1.19 (1.09 to 1.29), P < 0.001 |

| GFR (1 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.94), P < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95), P < 0.001 |

| Gender (0 = M; 1 = F) | 1.30 (0.71 to 2.38), P = 0.40 | 1.28 (0.70 to 2.34), P = 0.43 |

Data are expressed as hazard ratio, 95% CI, and P value. In the last column, the Shrinkage corrected hazard ratios (13) are also reported for all covariates (for details, see Statistical Analysis).

Figure 1.

Ramipril has no effect on the cumulative incidence of ESRD in normal BMI patients but markedly attenuates the risk of ESRD in overweight and obese patients. Crude, adjusted, and shrinkage-corrected hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of ramipril treatment for ESRD are reported in the insets.

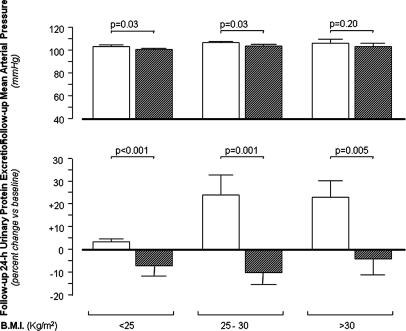

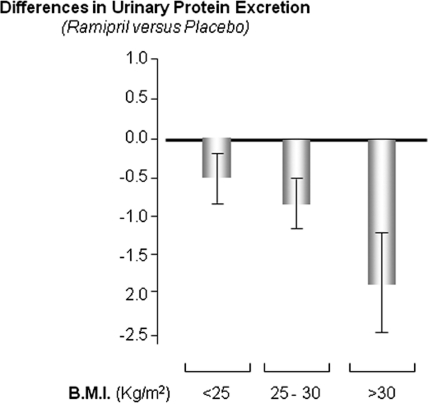

BMI, Proteinuria, and the Response to Ramipril

Baseline proteinuria did not differ across BMI and treatment strata (Table 1). At follow-up, mean arterial pressure significantly differed between the two study arms in overweight patients and in those with normal BMI, but these differences were clinically meaningless (Figure 2, top). No difference in BP burden was observed between the two study arms in obese patients. Twenty-four-hour urinary protein increased along with BMI categories in placebo-treated patients (Figure 2, bottom). The effect of ramipril on proteinuria was more pronounced in overweight and obese patients than in patients with normal BMI (Figure 2, bottom). Consistently, the difference between changes in proteinuria (mean ± SEM) observed in the two treatment arms during the follow-up period versus baseline was large (1.51 ± 0.55 g/24 h, P = 0.001), intermediate (1.14 ± 0.46 g/24 h, P = 0.02), and almost negligible (0.39 ± 0.37 g/24 h, P = 0.29) in the highest, middle, and lowest BMI group, respectively (Figure 3). The modification effect of BMI on the reno-protective effect of ramipril did not change appreciably when the analyses were adjusted for the diagnosis of the underlying renal disease (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Ramipril prevents the rise in proteinuria which occurrs during follow-up in overweight and obese patients. Mean arterial pressure (top) and percent changes (follow-up versus baseline) in 24-hour urinary protein excretion (bottom) in ramipril (■)- and placebo (□)-treated patients across BMI categories. Data are mean ± SE.

Figure 3.

The anti-proteinuric effect of ramipril is maximal on obese patients and minimal in patients with normal BMI. Differences in urinary protein excretion (follow-up − baseline) are expressed as mean and SE. Data were adjusted for all variables listed in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of the REIN study, obesity predicted a higher incidence of renal events in patients randomized to the placebo arm of the trial, but such a risk excess was abolished in those allocated to ramipril. As a result, the risk reduction for renal disease progression brought about by this drug was substantially more pronounced in obese than in nonobese patients. Furthermore, such an effect was paralleled by a more pronounced difference in proteinuria between ramipril- and placebo-treated obese patients than in overweight or normal BMI patients.

Obesity has now ascended to the top ranks among risk factors for CKD.6 Observational studies have coherently shown that, in patients with established renal diseases of various etiology, the presence of obesity accelerates the progression rate of the underlying nephropathies toward the end-stage phase.11–13 The causal role of obesity in renal function loss and proteinuria in the obese has been documented in various interventional studies including dietary and bariatric surgery interventions.11 Although mechanism(s) responsible for renal disease in obesity are incompletely understood, the renin-angiotensin system seems to be of peculiar relevance in this condition.12 High plasma renin, angiotensinogen, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and aldosterone levels are frequently observed in obese people,13,14 a phenomenon in part attributable to sympathetic overactivity15 in these patients. Of note, angiotensinogen and angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AII-R) mRNA are all expressed in the adipose tissue,16 and fat mass excess in obese individuals contributes to raise renin and AII levels in this condition.14 Glomerular hypertension apart, AII accelerates progression of renal disease also by other mechanisms, e.g., by inducing intrarenal inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and apoptosis.17 AII is a relevant modifier of adipokine production in fat tissue because AII blockade decreases TNF-α, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1), and markers of oxidative stress and increases adiponectin levels in a genetically obese mouse model 18. Thus, AII may directly or indirectly affect renal function and structure by several mechanisms in obese people. Collectively, these findings suggest that countering the renin-angiotensin system may be a peculiarly beneficial intervention in patients with CKD and high BMI.

Given the public health impact of obesity and the increasing concern of overweight and obesity in the epidemic of CKD worldwide,19 information on the efficacy of available drugs on the progression of CKD in overweight and obese patients with CKD is a question of clinical and public health relevance. In this study, we found that, in placebo-treated patients, overweight and obesity are associated with stepwise increases in the incidence rate of renal outcomes, which confirms previous observations.3 In addition, we showed for the first time that obese patients seem to be peculiarly sensitive to the nephroprotective effect of ramipril, because risk reduction for renal outcomes in these patients was substantially more pronounced than that in other BMI strata. Of note, this finding comes along with a more pronounced decline in proteinuria in obese and overweight patients compared with those with normal BMI. Proteinuria is a marker and a causal factor of renal disease progression. Although the effect of ACE inhibition was more pronounced in obese than in nonobese patients, the effect modification of BMI in the risk of progression to ESRD was largely independent of proteinuria, suggesting that mechanisms other than this risk factor are responsible for such a phenomenon.

Our study has limitations. This is a post hoc analysis generated from a randomized, controlled clinical trial including a relatively low number of obese patients. We did not randomize a priori within predefined BMI strata, and this may be a source of confounding. However, at baseline, there was minor unbalancing for gender, smoking habits, hemoglobin, and GFR across BMI strata. To overcome this limitation, we adjusted the analysis for potential confounders, and after such an adjustment, the effect of ramipril in obese people was substantially unmodified, suggesting that it is unlikely that the effect modification of BMI on the response to ramipril is the result of confounding. Some additional considerations support the credibility of our analysis. First, the interaction we found was quantitative rather qualitative, which makes it unlikely to merely be the result of chance.3 Second, direction of the expected effect was prespecified on the basis of a variety of observations in animal models and in humans. Third, the effect of ramipril in obese patients was large. Fourth, the reduction in the risk for progression to ESRD was consistent across closely related outcomes, including proteinuria. Post hoc analyses of other randomized clinical trials (external validation) and specific trials in the obese are needed to confirm our observations. Our data cannot be generalized to the population of patients with CKD secondary to diabetes. Furthermore, notwithstanding that the effect modification of BMI was independent of proteinuria, our findings may not apply to nonproteinuric nephropaties, an issue clearly deserving further study.

In conclusion, this post hoc analysis in the cohort of proteinuric patients with CKD enrolled in REIN indicates that the risk reduction for renal disease progression to ESRD and the anti-proteinuric effect by ramipril are more pronounced in obese than in overweight and normal BMI patients. These findings provide a solid basis for planning confirmatory analyses in other clinical trial databases and new trials specific to obese patients with CKD.

CONCISE METHODS

The REIN study is a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter clinical trial including 352 patients with chronic, nondiabetic nephropathies. This study assessed the effect of an ACE inhibitor (ramipril) on the evolution of the GFR over time, proteinuria, time to doubling of serum creatinine, and progression to ESRD. A detailed description of study protocols and main results of this trial are reported elsewhere.10

In this secondary analysis, we investigated the relationship between BMI and the incidence rate of renal events (either doubling in serum creatinine or ESRD) and tested whether BMI modifies the effect of ACE inhibitors on these outcomes. Because BMI was not available in 15 patients, this analysis was performed in 337 patients (96%). In brief, study participants were normotensive (arterial pressure < 140/90 mmHg without anti-hypertensive therapy) or hypertensive patients of both genders, 18 to 70 years of age, with creatinine clearance in the range of 20 to 70 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and persistent proteinuria (>1 g/24 h for at least 3 months).

After 1-month placebo run-in, patients were randomized to ramipril or placebo and followed up for an average time of 30 months (range: 0.2 to 76 months). For the purpose of this study, we considered as outcome measures time of ESRD occurrence and combined end-point including ESRD occurrence or time to creatinine doubling.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (normally distributed data), median and interquartile range (non-normally distributed data), or as percent frequency, and comparisons between groups were made with t test, Mann-Whitney test, or χ2 test, as appropriate.

The effect modification of BMI strata on the efficacy of ramipril for reducing the incidence rate of study outcomes (primary outcome: ESRD alone; secondary outcome: combined renal endpoint [ESRD or creatinine doubling]) was studied by crude and multivariate Cox regression analyses (time to the first event analysis). Multivariate models adjusted for gender and systolic BP (two established determinants of renal outcomes), as well as for variables that met criteria to be confounders (that is variables that were related [P < 0.20] with both, exposure [that is, ramipril/placebo treatment in each BMI stratum], and study outcomes, that were not an effect of exposure, and that were not in the causal pathway between the exposure and study outcomes). The proportionality assumption of Cox models was tested by the analysis of Schoenfeld residuals, and no violation was found. The competing effect of death on the relationship between BMI and ramipril treatment with renal events was modeled by competing risks analysis.20 Data are expressed as hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. The hazard rations of ramipril treatment across BMI categories (<25, 25 to 30, and >30 kg/m2) were calculated by the linear combination method (Supplemental Appendix 1). The multivariate Cox regression model for the combined renal endpoint (ESRD and doubling of serum creatinine) was of adequate statistical power (at least 10 events for each variable in the models), and a Shrinkage method21 was applied for adjusting for the same risk factors in the analysis of the main endpoint (ESRD). All calculations were made using standard statistical packages (SPSS for Windows Version 9.0.1, SPSS, Chicago, IL; STATA 9 for Windows, STATA, College Station, TX).

Organization of the REIN Study

Principal investigators: G. Remuzzi, G. Tognoni.

Study coordinator: P. Ruggenenti.

Investigators and Institutions

N. Bossini, B. F. Viola, F. Scolari, R. Maiorca (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Spedali Civili, Brescia); F. Cofano, G. Fellin, G. D'Amico (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale Provinciale S Carlo Borromeo, Milano); D. Dissegna, A. Brendolan, G. La Greca (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale S. Bortolo, Vicenza); A. Feriozzi, E. Ancarani (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale Grande di Viterbo, Viterbo); E. Gandini, I. D'Amato, A. Giangrande (Unitá Operativa di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale Provinciale, Busto Arsizio); G. Giannico, O. Vitale, C. Manno, F.P. Schena (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Policlinico, Bari); A. Mazzi, G. Garini, A. Borghetti (Istituto di Clinica Medica e Nefrologia, Parma); R. Pisoni, L. Mosconi, T. Bertani (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedali Riuniti, Bergamo); F. Scanferla, G. Bazzato (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi Ospedale Provinciale Umberto I, Mestre); E. Oliva, C. Zoccali (Divisione di Nefrologia Centro di Fisiologia Clinica del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Reggio Calabria); G. Toti, S. Sisca, Q. Maggiore (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Unitá Sanitaria Locale Zona 10H, Bagno a Ripoli); E. Pignone, R. Boero, G. Piccoli (Divisione di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale Zonale Giovanni Bosco, Torino); R. Piperno, A. Rosati, M. Salvadori (Unitá Operativa di Nefrologia e Dialisi, Ospedale Regionale Careggi-Monna Tessa, Firenze).

Database and Statistical Analyses

B. Ene Iordache, A. Remuzzi, A. Perna, R. Benini, L. Tammuzzo (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri).

Laboratory Measurements

F. Gaspari, F. Arnoldi, I. Ciocca, O. Signorini, S. Ferrari, D. Gritti, A. Roggeri, L. Del Priore, D. Cattaneo, N. Stucchi (Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri).

Independent Adjudicating Panel

L. Migone (chairman), E. Marubini (statistician), A. Del Favero, G. Ideo, E. Geraci, U. Loi.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a European Union grant [SysKid project, Framework Programme 7 (FP7)].

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “REIN on Obesity, Proteinuria and CKD,” on pages 990–992.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH: The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 9: 88, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Kinjo K, Inoue T, Iseki C, Takishita S: Body mass index and the risk of development of end-stage renal disease in a screened cohort. Kidney Int 65: 1870–1876, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Go AS: Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann Intern Med 144: 21–28, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ejerblad E, Fored CM, Lindblad P, Fryzek J, McLaughlin JK, Nyren O: Obesity and risk for chronic renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1695–1702, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elsayed EF, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Griffith JL, Kurth T, Salem DN, Levey AS, Weiner DE: Waist-to-hip ratio, body mass index, and subsequent kidney disease and death. Am J Kidney Dis 52: 29–38, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ritz E: Obesity and CKD: How to assess the risk? Am J Kidney Dis 52: 1–6, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bosma RJ, van der Heide JJ, Oosterop EJ, de Jong PE, Navis G: Body mass index is associated with altered renal hemodynamics in non-obese healthy subjects. Kidney Int 65: 259–265, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McClellan WM: The epidemic of renal disease: What drives it and what can be done? Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1461–1464, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wahba IM, Mak RH: Obesity and obesity-initiated metabolic syndrome: Mechanistic links to chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 550–562, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia). Lancet 349: 1857–1863, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navaneethan SD, Yehnert H, Moustarah F, Schreiber MJ, Schauer PR, Beddhu S: Weight loss interventions in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1565–1574, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bosma RJ, Krikken JA, Homan van der Heide JJ, de Jong PE, Navis GJ: Obesity and renal hemodynamics. Contrib Nephrol 151: 184–202, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tuck ML, Sowers J, Dornfeld L, Kledzik G, Maxwell M: The effect of weight reduction on blood pressure, plasma renin activity, and plasma aldosterone levels in obese patients. N Engl J Med 304: 930–933, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engeli S, Bohnke J, Gorzelniak K, Janke J, Schling P, Bader M, Luft FC, Sharma AM: Weight loss and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Hypertension 45: 356–362, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sowers JR, Whitfield LA, Catania RA, Stern N, Tuck ML, Dornfeld L, Maxwell M: Role of the sympathetic nervous system in blood pressure maintenance in obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 54: 1181–1186, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giacchetti G, Faloia E, Mariniello B, Sardu C, Gatti C, Camilloni MA, Guerrieri M, Mantero F: Overexpression of the renin-angiotensin system in human visceral adipose tissue in normal and overweight subjects. Am J Hypertens 15: 381–388, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruster C, Wolf G: Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2985–2991, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kurata A, Nishizawa H, Kihara S, Maeda N, Sonoda M, Okada T, Ohashi K, Hibuse T, Fujita K, Yasui A, Hiuge A, Kumada M, Kuriyama H, Shimomura I, Funahashi T: Blockade of Angiotensin II type-1 receptor reduces oxidative stress in adipose tissue and ameliorates adipocytokine dysregulation. Kidney Int 70: 1717–1724, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mathieu C, Teta D, Vogt B, Burnier M: [Obesity: what impact on renal function?] Rev Med Suisse 2: 576–581, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM: Statistics in medicine: Reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 357: 2189–2194, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M: Survival Analysis. A Self Learning Text, 2nd ed., New York, Springer, 2005 [Google Scholar]