Abstract

Earlier studies of influenza-specific CD8+ T cell immunodominance hierarchies indicated that expression of the H2Kk MHCI allele greatly diminishes responses to the H2Db-restriced DbPA224 epitope. The results suggested that the presence of H2Kk during thymic differentiation led to the deletion of a prominent Vβ7+ subset of DbPA224-specific TCRs. The more recent definition of DbPA224-specific TCR CDR3β repertoires in H2b mice provides a new baseline for looking again at this possible H2Kk effect on DbPA224-specific TCR selection. We found that immune responses to several H2Db- and H2Kb-restricted influenza epitopes were indeed diminished in H2bxk F1 versus homozygous mice. In the case of DbPA224, lower numbers of naïve precursors were part of the explanation, though a similar decrease in those specific for the DbNP366 epitope did not affect response magnitude. Changes in precursor frequency were not associated with any major loss of TCR diversity and could not fully account for the diminished DbPA224-specific response. Further functional and phenotypic characterisation of influenza-specific CD8+ T cells suggested that the expansion and differentiation of the DbPA224-specific set is impaired in the H2bxk F1 environment. Thus, the DbPA224 response in H2bxk F1 mice is modulated by factors that affect the generation of naïve epitope-specific precursors and the expansion and differentiation of these T cells during infection, rather than clonal deletion of a prominent Vβ7+ subset. Such findings illustrate the difficulties of predicting and defining the effects of MHCI diversification on epitope-specific responses.

Introduction

Despite the fact that viruses encode multiple proteins, virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) focus on a very limited number of peptide + class I MHC (pMHCI) epitopes. The relative magnitudes of antigen-expanded pMHCI-specific CTL populations often sort into reproducible hierarchies ranging from large (immunodominant) to small (subdominant) (1). Although many factors may determine the positioning of a given pMHCI complex within this hierarchy, the first requirement is that the peptide should access the nascent MHCI molecule during the course of infection, then bind in a way that is recognized by the available CD8+ T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire (1, 2). Underlying any repertoire effect is the fact that these same MHCI alleles that present viral peptides at the time of infection have earlier played a key role in TCR selection during thymocyte ontogeny. A number of studies have examined the impact of differences in MHCI haplotype and diversity on the generation of epitope-specific CD8+ T cell responses in mice (3–8) and humans (9–11), providing some evidence that the presence of particular MHCI alleles can modify responses to peptides presented by other MHCI molecules. Possible mechanisms to explain this effect include changes in the thymic selection of TCRs specific for an individual epitope (6, 10) and altered epitope presentation during infection (11–13). The latter could reflect modulation of MHCI cell surface expression depending on the combination of MHCI alleles expressed (13, 14) or that competition for overlapping peptides during infection has the potential to modify epitope processing or presentation (11, 15). Clearly, such MHCI-related effects on response magnitude are of interest as we seek to understand and manipulate CTL-mediated immunity in MHC-polymorphic human populations.

An accumulating body of evidence suggests that epitope-specific TCR diversity plays a part in determining the quality of virus-specific CTL responses and the outcome of infection. More diverse repertoires have been shown to include TCRs with a range of structures and avidities, allowing a spectrum of response profiles that provide better protection against virus infection (16) and minimize the possibility of mutational escape from CD8+ T cell-mediated immune control (17). This has led to the suggestion that vaccination, particularly to protect against viruses (like HIV and influenza) that readily generate mutants, should optimally prime memory T cell populations with a high level of TCR diversity. Given the role for MHC alleles in shaping the available TCR repertoire (5, 10, 16, 18), it is important to understand how differences in MHCI haplotype are likely to impact on the frequency, range and properties of the epitope-specific TCRs selected by immunization and/or infection.

Early studies of influenza epitope-specific CD8+ T cell responses in mice indicated that expression of the MHCI allele H2Kk greatly diminishes the magnitude of H2Db-restricted responses (4, 8). Subsequent experiments narrowed this effect down to a particular epitope-specific population, demonstrating that virus-infected B6xC3HF1 (B6C3F1, H2bxk) mice mount significantly smaller responses to the DbPA224 epitope (acid polymerase, residues 224–233 complexed with H2Db) compared to C57BL/6 (B6, H2b) mice (3). In contrast, responses to the other immunodominant DbNP366 epitope (nucleoprotein, residues 366–374 complexed with H2Db) were equivalent between the two mouse strains following primary infection. The diminished CD8+DbPA224+ responses in the F1 mice looked to be associated with the deletion of a prominent Vβ7+ subset of DbPA224-specific TCRs, supporting the idea that thymic development of naïve CD8+DbPA224+ precursors in the presence of H2Kk had led to a specific ‘hole’ in this TCR repertoire. This result was recorded at a very early stage of our understanding of the antigen-selected CD8+DbPA224+ response, way before we had any capacity to measure naïve T cell numbers and accurately compare TCR repertoires. Having much better tools available, we repeated this analysis in B6C3F1 mice, with the intent of achieving a much more rigorous definition of the impact of MHCI diversification and possible cross-tolerance (during thymic differentiation) on the selection and expansion of DbPA224-specific CD8+ T cells during influenza virus infection.

While the current study confirmed a significant reduction in the magnitude of the DbPA224-specific response in H2bxk F1 mice, it further identified reduced responses to the subdominant epitopes KbPB1703 (polymerase B1, residues 703–711 complexed with H2Kb), DbPB1F262 (polymerase B1 +1 reading frame, residues 62–70 complexed with H2Db) and KbNS2114 (non-structural protein 2, residues 114–121 complexed with H2Kb) in F1 compared to B6 mice at all time points examined. Thus, several responses appear to be diminished as a result of MHCI diversification and cross-tolerance. Furthermore, it now seems that our previous conclusion that the CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ set is substantially missing from the B6C3F1 response may have resulted from the selective deletion of these high avidity T cells during the process of generating peptide-stimulated CD8+DbPA224+ cell lines for analysis of Vβ usage. Although the numbers of naïve CD8+DbPA224+ precursors were reduced in B6C3F1 compared to B6 mice, this was not associated with major changes in TCRβ repertoire diversity and could not fully account for the diminished response during infection. Overall, it seems that influenza-specific CD8+ T cell responses in B6C3F1 mice may be impeded by factors that affect both the generation of naïve CTL precursors and the expansion and differentiation of these precursors subsequent to infection.

Materials and Methods

Mice and virus infections

The C57BL/6J (B6, H2b), C3H/HeJ (C3H, H2k) and B6xC3HF1 (B6C3F1, H2bxk) mice were bred and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at The University of Melbourne (Parkville, Australia). For analysis of primary responses to influenza virus, mice were anesthetized by methoxyfluorane inhalation and infected intranasally (i.n.) with 104 pfu of the A/HK-x31 virus (HKx31, H3N2) in 30 ml PBS. Recall responses were examined in mice that were firstly primed intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1.5×107 pfu of the A/PR8/34 (PR8, H1N1) virus at least 6 weeks before i.n. infection with the HKx31 virus. Memory responses were analysed 6 weeks after i.p. priming with either the WT or recombinant (19, 20) PR8 viruses. Virus stocks were amplified in the allantoic cavity of day 10 embryonated chicken eggs and virus titres were determined by plaque assay as pfu on monolayers of Madin Darby canine kidney cells (21). All experiments were performed with the approval of The University of Melbourne Animal Ethics Committee.

Tissue sampling and cell preparation

Lymphocytes were recovered from the infected airways of mice by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and incubated on plastic for 1 h at 37°C to remove adherent cells. Single cell suspensions were prepared from spleens by pressing through 70 mm cell strainers. In some instances spleen cells were treated with Tris-buffered ammonium chloride to lyse RBCs.

Kinetics of virus infection

For determination of the kinetics of pulmonary virus infection in B6 and B6C3F1 mice, either naïve or PR8-primed mice were infected i.n. with the HKx31 virus. At various intervals after infection, lungs were removed and homogenized in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) containing 100 U/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin (both Invitrogen) and 24 µg/ml gentamicin (Sterisafe). Virus present in lung homogenates was quantified by plaque assay as above.

Tetramer and antibody staining

Lymphocytes were plated at 0.5–2×106 cells and incubated with the DbNP366, DbPA224, KbPB1703, DbPB1-F262 and KbNS2114 tetramers (ImmunoID) conjugated to either PE or allophycocyanin for 1 h at room temperature. After washing cells were stained for CD8a and, in some instances, for CD62L. For analysis of Vβ usage, splenocytes from naïve mice or tetramer-stained splenocytes from mice sampled on d10 after HKx31 infection were stained with anti-CD8α-PerCPCy5.5 (53-6.7, BD Pharmingen) and a panel of 14 FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific for various Vβ families (BD Pharmingen). To identify antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells, splenocytes were stained with anti-CD8α-APC (53-6.7, Biolegend) and anti-CD11α-FITC (2D7, Biolegend). For analysis of cell surface H2Db and H2Kk expression, splenocytes from naïve mice were treated to lyse erythrocytes and then incubated in Fc block (spent 2.4G2 supernatant with 0.5% normal mouse serum and 0.5% normal rat serum). Cells were then stained with anti-H2Db-FITC (KH95, BD Pharmingen) and anti-H2Kk-FITC (36-7-5, Biolegend). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and the data analyzed by either CellQuest Pro (BD Immunocytometry Systems) or FlowJo (Tree Star Inc.) software.

Sorting, single cell PCR and sequencing

Single CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ or CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ cells were sorted on a BD FACS Aria (BD Immunocytometry systems) into the wells of a 96-well PCR plate. cDNA was synthesised and Vβ8.3+ or Vβ7+ transcripts amplified and sequenced as described previously (22, 23). The TCR gene nomenclature used here is according to Arden et al. (24).

Tetramer enrichment

Enumeration of influenza epitope-specific CD8+ precursors in naïve B6 and B6C3F1 mice was performed using a protocol of magnetic enrichment and flow cytometric detection of tetramer binding cells (25) adapted by La Gruta et al. (26). Single cell suspensions were prepared from spleens and lymph nodes (axillary, brachial, cervical, inguinal, lumbar, mediastinal, mesenteric, pancreatic and renal) of naïve mice. Cells were stained with PE-labelled DbNP366 or DbPA224 tetramers in Fc block (spent 2.4G2 supernatant with 0.5% normal mouse serum and 0.5% normal rat serum), then washed in cold sorter buffer (PBS containing 0.5% BSA (Gibco) and 2 mM EDTA (Ajax Finechem)) and labelled with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). After further washes, cells were passed over a magnetized LS column (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells bound by the column were eluted and stained with anti-CD11b-FITC, anti-CD11c-FITC, anti-B220-FITC, anti-F4/80-FITC, anti-CD8a-allophycocyanin-Cy7, anti-CD4-PE-Cy7, anti-CD3e-PerCPCy5.5 and anti-CD62L- allophycocyanin (all BD Pharmingen). Samples were acquired on a BD LSR II (BD Immunocytometry systems). FITC-conjugated antibodies formed a dump gate to exclude cells that non-specifically bound to tetramers. DbNP366 and DbPA224-specific CD8+ naïve precursors were identified as Dump−CD3+CD4−CD8+tetramer+ cells, with mostly a CD62Lhi phenotype.

Stimulation of CD8+ T cells and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS)

Lymphocytes were plated at 0.5–2×106 cells and incubated for 5 h either in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3ε (145-2C11, BD Pharmingen) or 1 µM (or graded concentrations for peptide titration experiments) of NP366–374 (ASNENMETM) (27), PA224–233 (SSLENFRAYV) (28) or NP50–57 (SDYEGRLI) (29) peptides (Auspep) with 10 U/ml human rIL-2 (Roche) and 1 µg/ml Golgi-plug (BD Biosciences) (30). Cells were then stained for surface expression of CD8a and intracellular IFN-γ, TNFα and IL-2 (30). Background levels of staining were determined using controls incubated in the absence of peptide or anti-CD3ε, and were subtracted from percentages obtained for samples incubated in the presence of peptide or anti-CD3ε.

Tetramer elution assay

The TCR avidities of DbNP366- and DbPA224-specific populations from B6 and B6C3F1 mice were compared using a tetramer elution assay (30). Splenocytes (0.5–2×106 cells) were stained with the DbNP366-PE or DbPA224-PE tetramers for 1 h at room temperature to label epitope-specific populations. Cells were washed and then incubated in the presence of 5 mg/ml anti-H2Db (28-14-8; BD Pharmingen) at 37°C. At designated time points, cells were removed onto ice, washed, then stained for CD8a expression and analysed by flow cytometry for residual tetramer staining.

Statistical analysis

All statistical comparisons were performed using an unpaired Student’s t test.

Results

Reduced H2Db-, H2Kb- and H2Kk-restricted responses in H2bxk F1 mice

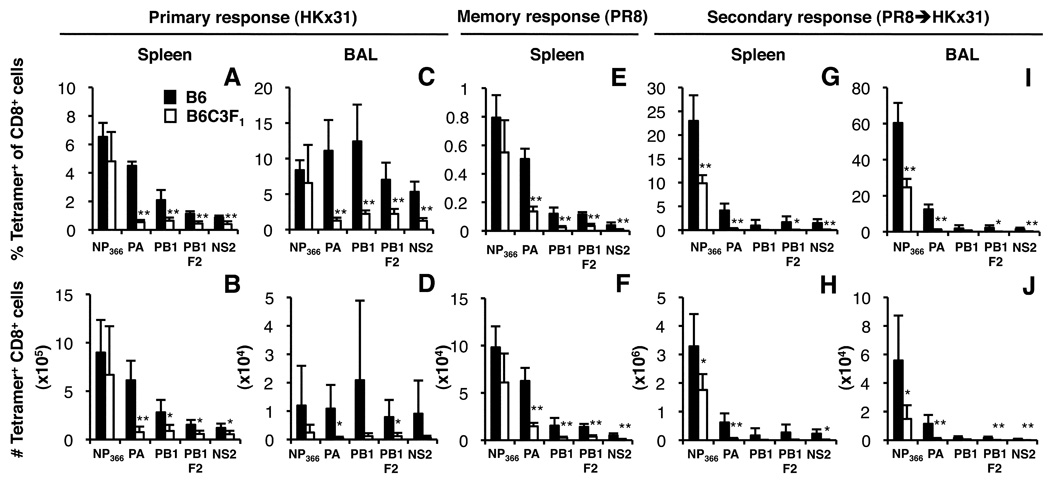

The present experiments extend our earlier IFN-g ICS assay comparison (3) of CTL responses following HKx31 influenza A virus infection of naïve and ‘memory’ B6C3F1 (H2bxk) and B6 (H2b) mice by using tetramer staining reagents representing the DbNP366, DbPA224, KbPB1703, DbPB1F262 and KbNS2114 epitopes. Analysis of CTLs from the spleen and infected airways (BAL) 10 d following primary infection with the HKx31 virus (Fig. 1A–D) confirmed (3) that the numbers of CD8+DbPA224+ cells were approximately 8-fold lower in the F1 spleen and 20-fold lower in the F1 BAL (Fig. 1B, D). The ‘minor’ KbPB1703, DbPB1F262 and KbNS2114 responses were also significantly diminished in the F1 mice, but only by 2–3-fold (spleen, Fig. 1B). Thus, of the five H2b-restricted epitopes examined, only the DbNP366 response was not significantly reduced in the heterozygotes, though, it was repeatedly observed to be slightly lower (Fig. 1A–D). As such, the immunodominance hierarchy (Fig. 1A, B) in B6C3F1 mice (DbNP366>DbPA224=KbPB1703=DbPB1-F262=KbNS2114) differs from that for the B6 parent (DbNP366=DbPA224>KbPB1703=DbPB1-F262=KbNS2114).

FIGURE 1.

Virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in B6 (H2b) and B6C3F1 (H2bxk) mice after primary or secondary challenge with influenza viruses. For analysis of acute responses, naïve and PR8-primed mice were infected i.n. with the HKx31 virus and spleen and BAL lymphocyte populations were harvested on d10 (primary; A–D) or d8 (secondary; G–J) after infection. Memory responses generated by priming i.p. with the PR8 virus were analysed in the spleen 6 weeks after priming (memory; E, F). Cells were stained with the DbNP366, DbPA224, KbPB1703, DbPB1F262 and KbNS2114 tetramers conjugated to PE or allophycocyanin, followed by anti-CD8α-PerCPCy5.5. Data show the mean proportion and number of influenza epitope-specific CD8+ T cells ± SD for 5 mice. * p<0.05, **p<0.01 comparing parent and F1.

Secondary responses were analysed in mice immunized i.p. at least 6 weeks previously with the H1N1 PR8 virus, then challenged i.n. with the serologically distinct H3N2 HKx31 virus (Fig. 1 G–J) that shares the immunogenic PR8 internal proteins. Although the numbers of DbNP366-specific CD8+ memory T cells in B6 and B6C3F1 mice were not significantly different after PR8 priming ((3) and Fig. 1E,F), further expansion following secondary challenge established that there was indeed a reduction in the F1 spleen (2-fold, Fig. 1H) and BAL (4-fold, Fig. 1J). In fact, the recall responses to all epitopes were generally lower in the heterozygotes (Fig. 1G–J).

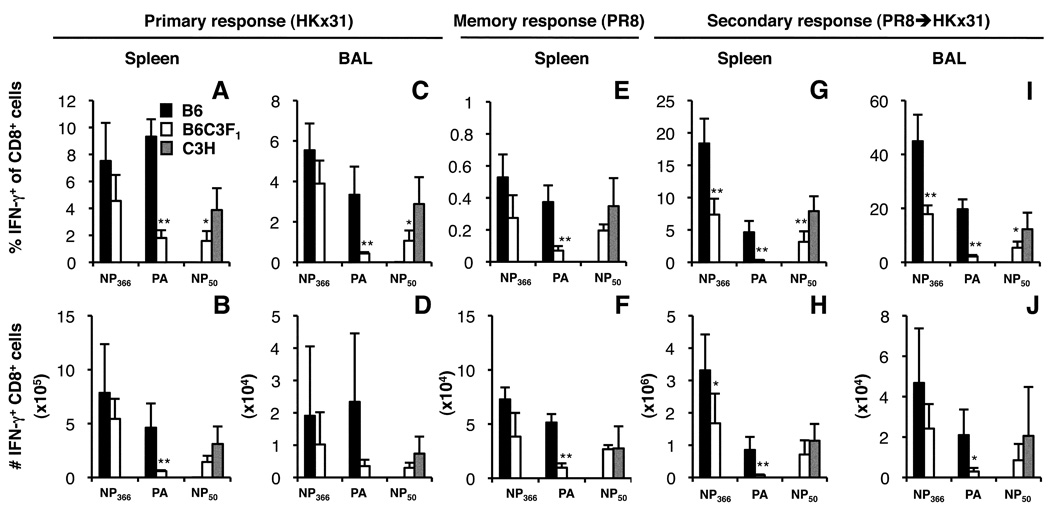

A lack of published data on H2k-restricted epitopes recognised in C3H mice limited our ability to compare the influenza-specific CD8+ T cell responses in C3H and F1 mice (3, 31). However, to demonstrate that F1 mice generated responses to both H2b- and H2k-restricted viral peptides, we compared primary (Fig. 2A–D), memory (Fig. 2E, F) and recall (Fig. 2G–J) responses to the DbNP366, DbPA224 and KkNP50 epitopes for the parental and F1 mice using an IFN-g ICS (30) assay as we did not have tetramer reagents available for the KkNP50 epitope. The percentages of DbPA224- and KkNP50-specific CD8+ cells were significantly reduced following primary and secondary challenge of F1 mice, though, as found previously with the tetramers (Fig. 1E–H), this was only apparent for the secondary response to DbNP366 (Fig. 2G–J).

FIGURE 2.

The KkNP50 response in B6C3F1 mice. Naïve and PR8-primed B6, B6C3F1 and C3H mice were infected i.n. with the HKx31 virus and spleen and BAL populations were analysed on d10 (primary, A–D) or d8 (secondary, G–J). Memory responses generated by priming i.p. with the PR8 virus were also analysed in the spleen 6 weeks after priming (memory, E, F). Cells were stimulated for 5 h with or without 1 mM of the NP366, PA224 or NP50 peptides and stained for CD8a and intracellular IFN-γ. The percentages (A, C, E, G, I) and numbers (B, D, F, H, J) of IFN-γ+CD8+ cells were calculated. Mean ± SD for 5 mice. * p<0.05, **p<0.01 comparing F1 and inbred parent.

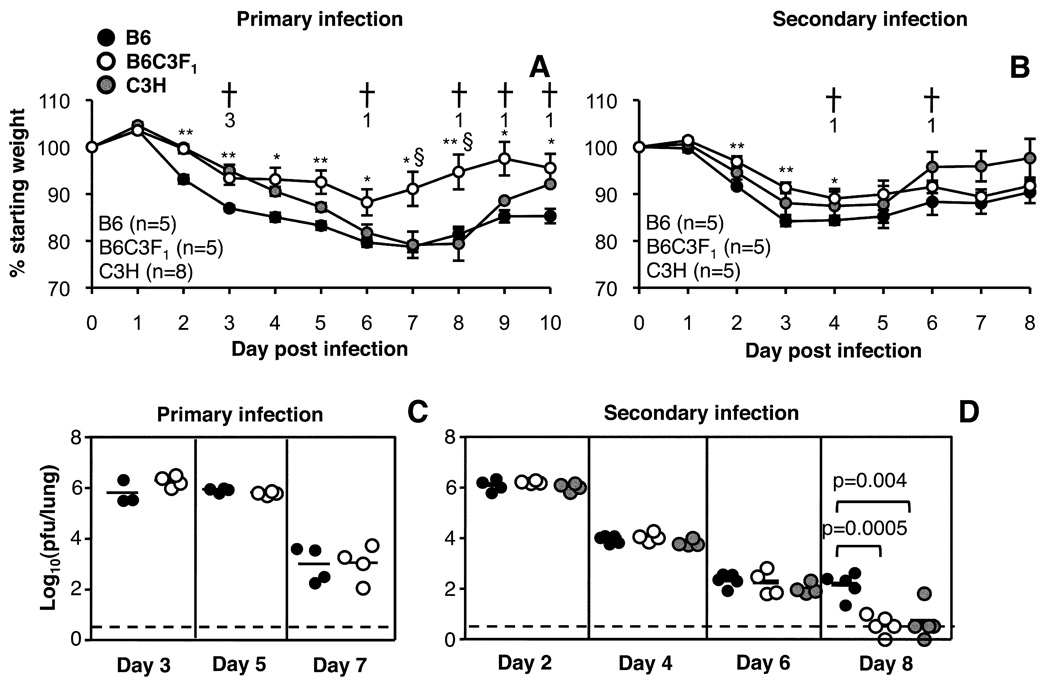

Pathogenicity of influenza virus infection in parental and F1 mice

Since B6C3F1 mice generate a broader CD8+ T cell response targeted towards a greater number of viral peptides (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), we reasoned that F1 mice might control influenza more rapidly than the B6 parents, which may in turn lead to reduced epitope-specific CTL responses (32). The kinetics of body weight loss and viral clearance were thus compared following primary or secondary challenge of F1 and inbred parental mice (Fig. 3). F1 mice lost significantly less weight compared to both parent strains following primary infection (Fig. 3A). Profiles of weight loss were more similar between the three strains following secondary infection, though B6 mice lost more weight compared to F1 mice between d2-d4 (Fig. 3B). There was a high mortality rate amongst C3H mice following primary infection (7/8 mice), which was reduced when the mice were primed with the PR8 virus i.p. before secondary challenge i.n. (2/5 mice) (Fig. 3A, B). This susceptibility to influenza infection may be influenced by a mutation in the TLR4 gene of C3H mice (33), which could make these mice more susceptible to secondary bacterial infections (34), particularly in the absence of pre-existing immunity to influenza virus (Fig. 3A, B).

FIGURE 3.

Kinetics of virus clearance in B6, B6C3F1 and C3H mice. Patterns of weight loss were compared over time following primary (A) or secondary (B) challenge with the HKx31 virus. Data show mean ± SE. Crosses and numbers indicate days on which C3H mice succumbed to infection. Lungs were taken for virus titration on d3, d5 and d7 after primary (C) or d2, d4, d6 and d8 after secondary (D) infection. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay (pfu/lung) of lung homogenate. The results shown are for individual mice, with means indicated by horizontal lines. The dotted line indicates the limit of detection for the plaque assay (100.52 pfu/ml).

Neither peak titres nor the kinetics of virus clearance differed following primary infection (Fig. 3C), indicating that the reduced magnitude of epitope-specific CD8+ T cell responses observed in F1 mice (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2) is not accounted for by any divergence in viral load. However, following secondary challenge, although maximal lung virus titres were comparable for B6, C3H and F1 mice (Fig. 3D, d2), the C3H and F1 mice cleared the virus slightly faster (Fig. 3D, d8) indicating that there are strain-specific differences in the kinetics viral clearance.

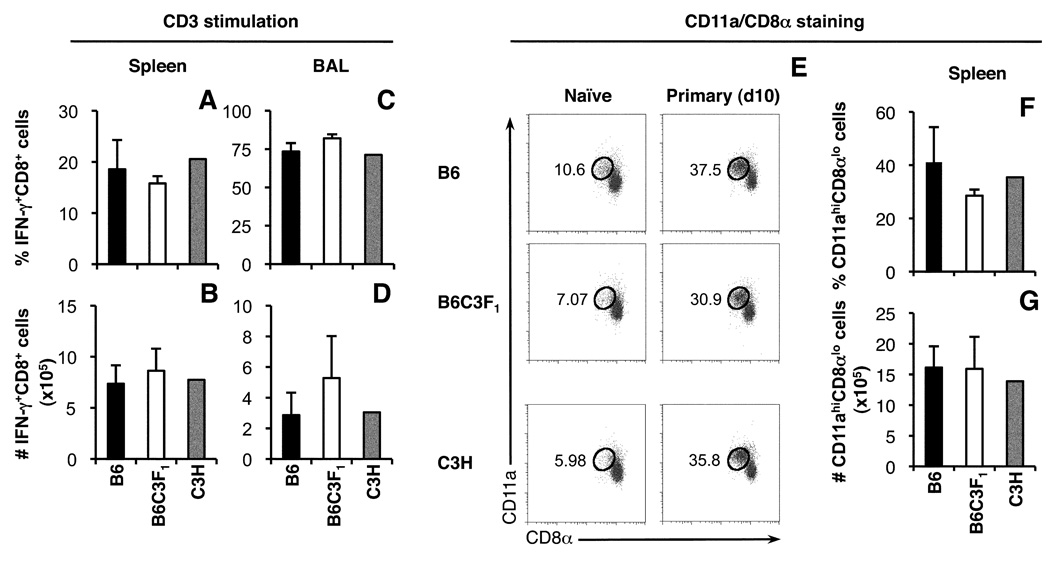

Similar estimates of the total influenza-specific CD8+ T cell response in H2b, H2K and H2bxk F1 mice

It was possible that the total size of the influenza-specific CD8+ T cell response differed in B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice. With only limited information available on the H2k-restricted influenza epitopes recognised in C3H and F1 mice, it was not feasible to enumerate the total influenza-specific CD8+ T responses in these mice via tetramer staining or peptide stimulation and IFN-γ detection. We therefore used short-term (5 h) stimulation with anti-CD3 to estimate the size of the total IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cell populations in F1 and parental mice, reasoning that during the acute stage of the CD8+ T cell response to influenza virus infection, the majority of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells in the spleen and BAL would be influenza-specific. Indeed, following primary challenge with the HKx31 virus, the proportion of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells detected in the spleens of B6 mice (18.6±5.7%, Fig. 4A) correlated well with the proportion of total influenza-specific CD8+ T cells calculated by adding up all the H2b-restricted responses measured by tetramer staining (∼15%, Fig 1A). However, the proportion of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells detected in the BAL of B6 mice (73.4±5.5%, Fig. 4C) exceeded the proportion of influenza-specific CD8+ T cells identified by tetramer staining (∼44.3%, Fig 1.C), which could reflect non-specific recruitment of memory CD8+ T cells into the lung airways during infection (35). Following primary infection, similar proportions and numbers of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells were detected in the spleen and BAL of B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice (Fig. 4A–D), suggesting that the sizes of the total primary influenza-specific CD8+ T cell responses are roughly equivalent for the three strains.

FIGURE 4.

Estimates of the overall size of the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in B6, B6C3F1 and C3H mice. Lymphocytes from the spleen and BAL of HKx31-infected mice were stimulated for 5 h with plate-bound anti-CD3ε antibody and the frequency (A, C) and number (B, D) of IFN-γ+CD8+ cells determined. Data are representative of two independent experiments and show mean ± SD for 5 B6 and B6C3F1 mice and the mean for 2 out 5 surviving C3H mice. Profiles of CD11α up-regulation and CD8α down-regulation were used to identify antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells in the spleens of naïve mice and mice infected with the HKx31 virus 10 days previously (E). The frequency (F) and number (G) of CD11αhiCD8αlow CD8+ T cells in the spleens of HKx31-infected mice were compared.

Another strategy to compare the size of the influenza-specific CD8+ T cell responses in B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice is examination expression levels of CD11a and CD8α to identify and enumerate antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells (CD11ahiCD8αlow) (7). In naïve mice, <11% of total CD8+ T cells in the spleen displayed a CD11αhiCD8αlow antigen-experienced phenotype (Fig. 4E). Primary influenza infection led to a substantial increase in the frequency of CD11ahiCD8αlow CD8+ T cells (approaching 40% of all CD8+ T cells in the spleen) and there were no significant differences in the proportion and number of CD11ahiCD8αlow CD8+ T cells between mouse strains. Thus, according to at least two measures, B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice appear to generate similar sized CD8+ T cell responses to influenza virus infection.

Prevalence of epitope-specific CTL precursors in naïve H2bxk F1 mice

It has been suggested that the number of epitope-specific CTL precursors (CTLps) can substantially influence response magnitude during infection (5, 25, 26, 36). The recent refinement of enrichment/flow cytometry-based protocols (26) allows the reproducible recovery of epitope-specific CTLps from naïve secondary lymphoid tissue. We applied this technique to determine whether differences in the DbPA224+ CTLp frequency for B6 and B6C3F1 mice contributed to the reduced response to this epitope in heterozygous mice. Numbers of DbNP366+ CTLps were also determined, as this was the only epitope-specific response that approached a similar magnitude in F1 and B6 mice following primary infection. Interestingly, the naïve DbNP366+ CTLp counts were diminished (Fig. 5) 1.7-fold in the B6C3F1 mice (11.1±5.8/mouse) compared with the B6 (18.5±5.2/mouse) controls (p≤0.04), which perhaps explains the earlier observation that F1 DbNP336+CD8+ numbers tended to be slightly lower following primary infection and priming with the PR8 virus (Fig. 1A–F and Fig. 2A–F). The prevalence of the naive DbPA224+ CTLp set was reproducibly 2-fold lower (p≤0.01) in B6C3F1 (27.8±9.8/mouse) compared to B6 mice (63.8±27.5/mouse). Even so, it is important to note that, despite a 2-fold reduction, the number of DbPA224-specific CTLps in the heterozygotes is still significantly greater than the number of DbNP366+ CTLps (Fig. 3; p≤0.005). Furthermore, the overall decrease in magnitude for the splenic DbPA224-specific response in B6C3F1 versus B6 mice was at least 8-fold following primary infection (Fig 1). Thus, whilst the diminished availability of DbPA224+ CTLps in B6C3F1 mice may contribute to a reduced response to this epitope during infection, it appears that additional mechanisms are influencing the extent of antigen-driven clonal expansion.

FIGURE 5.

Lower precursor frequencies of naïve DbNP366- and DbPA224-specific CD8+ T cells in unprimed H2bxk mice. Epitope-specific CD8+ T cell precursors were identified from pooled lymphoid tissues (25, 26). Data show total numbers of DbNP366- and DbPA224-specific CD8+ T cell precursors found in individual B6 and B6C3F1 mice, with the lines indicating the mean for each group.

Characterisation of TCRVβ usage in parental and F1 mice

Differences in MHCI haplotype and genetic background can impact on the selection of immune repertoires and the availability of epitope-specific TCRs (5, 16, 37). To determine whether the reduced generation of CD8+DbPA224+ and CD8+DbNP366+ cells in B6C3F1 mice was associated with modified thymic TCR repertoire selection and possible deletion of particular TCR clonotypes, we compared the prevalence of mAb-defined TCRVβ families for all CD8+ T cells from naïve B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice (Fig. 6A). Overall, this global measure of Vβ frequency indicated that CD8+ T cells from B6C3F1 and C3H mice were more likely (than B6 mice) to express Vβ2, 6, 8.1/8.2. 8.3 and 14, but less likely to stain for Vβ3, 5.1/5.2 and 12. Most striking was the minimal use of Vβ5.1/5.2 by C3H and B6C3F1 mice (1.1±0.1% and 0.4±0.1% respectively) relative to the B6 strain (13.6±0.7%). Thus, the TCRβ repertoire in C3H and B6C3F1 mice differs in some respects from that selected in the B6 strain, suggesting that either C3H non-MHC background genes or the presence of the H2k haplotype is in some way influencing the emergence of particular Vβ families. However, looking at the results (Fig. 6A) for the Vβ8.3 and Vβ7 families that are used prominently in the B6 response to DbNP366 and DbPA224 respectively, there were no dramatic differences in prevalence between the F1 and parent.

FIGURE 6.

Profiles of Vβ usage for naïve and immune DbNP366- and DbPA224- tetramer+CD8+ T cells from parental and F1 mice. (A) Splenocytes from naïve B6, B6C3F1 and C3H mice were stained with anti-CD8a-allophycocyanin and a panel of FITC conjugated mAbs specific for 14 Vβ regions. (B, C) Mice were infected i.n. with the HKx31 virus and profiles of Vβ staining on d10 are shown for DbNP366- (B) or DbPA224-specific (C) splenocytes. The protocol utilized allophycocyanin conjugated tetramers and anti-CD8α-PerCPCy5.5. Mean ± SD values are shown for 3 mice per group. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01 comparing B6C3F1 with B6; § p<0.05, §§ p<0.01 comparing B6C3F1 and C3H.

Our previous analysis described the absence of Vβ7+ cells from in vitro expanded DbPA224-specific B6C3F1 CTL lines with the conclusion the lack of response was due to a “hole” in the available B6C3F1 repertoire (3). A concern with using this approach to measure Vβ prevalence is that it relies on stimulation with high doses of peptide that may lead to loss of CTLp with high TCR/pMHC avidity (30). The analysis has thus been revisited using contemporary tetramer and antibody staining to measure Vβ usage by DbNP366- and DbPA224-specific CD8+ cells taken directly ex vivo from influenza virus-infected B6 and B6C3F1 mice (Fig. 6B, C). In B6 mice, Vβ8.3+ TCRs are very prominent (Fig. 6B, 42.3±37.3%) in the DbNP366-specific response (22, 38), whilst Vβ7 predominates (Fig. 6C, 55.1±8.7%) for the DbPA224-specific set (3, 23). These Vβ profiles were essentially unaltered in the B6C3F1 mice, with the CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ and CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ populations representing the major Vβ families used (65±17.1% and 62±03.1% respectively). While expression of most subdominant Vβ families was similar for CD8+DbNP366+ and CD8+DbPA224+ cells from B6 and F1 mice, the prevalence of Vβ4 TCRs was increased amongst F1 CD8+DbPA224+ cells (Fig. 6C, p<0.05). Thus, at this global level, MHC diversification in B6C3F1 mice has not substantially perturbed the epitope-specific TCRβ repertoires. The previous interpretation that CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ cells are deleted in B6C3F1 mice during development thus appears to be an artefact resulting from the use of high dose peptide-stimulation to generate in vitro CTL lines.

Similar CDR3β repertoires for CD8+DbNP366+ and CD8+DbPA224+ cells from B6 and B6C3F1 mice

It was possible that the DbPA224-specific Vβ7+ TCRβ repertoire in the B6C3F1 mice might be altered without any obvious change in the overall profile of Vβ usage. This was addressed by comparing the findings for single cell CDR3β sequence analysis of CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ cells from influenza-infected B6C3F1 mice with the extensive published data for the B6 parent (19, 23, 39). The CDR3β repertoire of CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ cells (22), which also establish slightly lower precursor frequencies in B6C3F1 and B6 mice (Fig. 5), was analysed concurrently and summarized in Table I with the F1 CDR3β sequences listed in Supplementary table I (CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ repertoire) and II (CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ repertoire). No differences were found in the TCRβ repertoires of CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ or CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ cells from B6 and B6C3F1 mice. Furthermore, the majority of CDR3β sequences obtained from B6C3F1 mice represent published clonotypes found previously in B6 homozygotes (Supplementary table I and Supplementary table II). Thus, the reduced frequency of DbPA224+CD8+ cells in B6C3F1 mice does not appear to reflect any impaired selection of Vβ7+ DbPA224-specific TCRs. Similarly, obvious differences in TCRβ usage do not explain the reduced number of DbNP366+ CTLps in F1 mice.

TABLE 1.

Summary of CDR3b sequence analysis for CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ and CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ cells from B6C3F1 mice after primary infection.

| CD8+DbNP366+Vβ8.3+ | CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ | |

|---|---|---|

| # Mice analysed | 5 | 5 |

| # TCRβ sequences | 344 | 277 |

| Dominant Jβa | 2S2 (61.2±9.7%) | 1S1 (14.0±13.0%), 1S5 (13.6±7.4%), 2S6 (11.6±8.7%) |

| Modal CDR3β lengtha |

9 aa (63.2±8.8%) | 6 aa (43.8±13.8%) |

| Clonotypes/mouseb | 5.6 ± 2.1d | 18.8 ± 2.5e |

| # Public or repeated clonotypesc |

3 (83.6±14.9%) | 0 (0.0±0.0%) |

> 10% of sequences.

Mean ± SD for 5 mice

Found in at least 4 out of 5 mice

7.9 ± 2.5 clonotypes/mouse found in B6 (H2b) mice (ref (23))

20.6 ± 3.8 clonotypes/mouse found in B6 (H2b) mice (ref (24))

Values in parenthesis indicate the mean proportion ± S.D. of sequences from individual mice with the characteristic indicated

Functional and phenotypic differences in influenza-specific CD8+ T cells from F1 and B6 mice

A 2-fold reduction in DbPA224+ CTLp frequency appeared insufficient to explain the substantial 8-fold reduction in the B6C3F1 DbPA224+CD8+ response following infection. Furthermore, we had failed to identify differences in the F1 DbPA224-specific TCRb repertoire that could account for this discrepancy. We thus asked whether some difference in the quality of the F1 DbPA224+CD8+ cells might correlate with this poor expansion during infection.

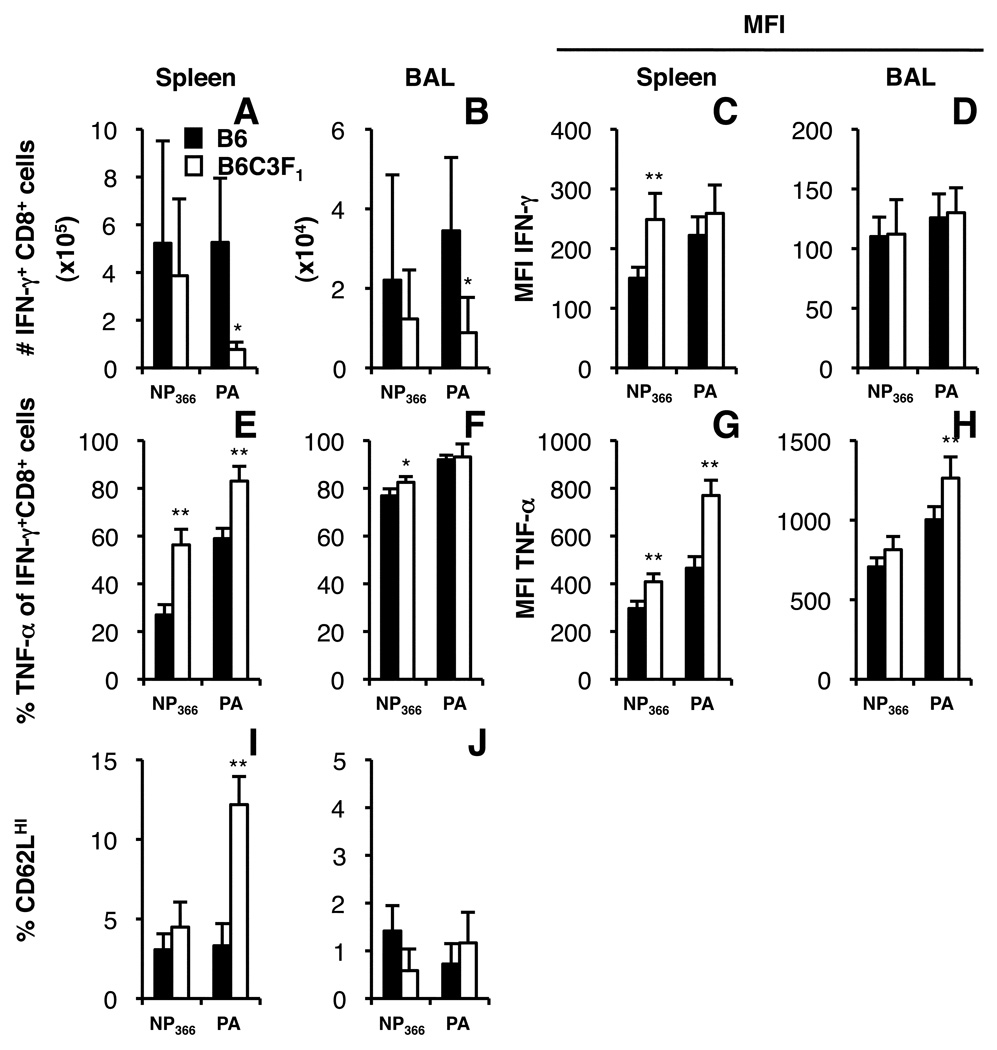

Immune CD8+ cells were recovered from the BAL and spleens of F1 and B6 mice on day 8 after infection with the HKx31 virus and stimulated with the NP366 or PA224 peptides to see if there was any difference in the cytokine production profiles. Overall, the numbers of CD8+DbNP366+ and CD8+DbPA224+ cells producing IFN-g (Fig. 7A, B) were equivalent to the counts detected by tetramer staining (data not shown) and the level of cytokine production (measured as mean fluorescence intensity, MFI) differed only for the DbNP366-specific set from spleen (Fig. 7C, D). However, looking within the splenic CD8+IFN-γ+ population, a greater proportion of both the DbNP366 and DbPA224-specific CD8+ cells from B6C3F1 mice produced TNF-a (Fig. 7E, F) and at higher MFI levels than in the B6 parent (Fig. 7G, H). These B6/F1 differences in TNF-α profiles were much less evident for the highly activated BAL populations (Fig. 7F, H).

FIGURE 7.

Functional and phenotypic differences in influenza-specific CD8+ T cells from B6 and B6C3F1 mice. Mice were infected with the HKx31 virus and spleen and BAL populations were recovered on d8. Cytokine expression was analysed after in vitro stimulation for 5 h with or without 1 µM NP366 and PA224 peptide. Cells were stained for expression of CD8α, IFN-γ (A–D) and TNF-α (E–H). Data show mean numbers of CD8+IFN-γ+ cells after peptide stimulation of spleen and BAL populations (A, B), the proportion of these cells producing TNF-α (E, F) and the mean fluorescence intensity of IFN-γ (C, D) and TNF-α staining (G, H). CD62L expression was characterised on CD8+DbNP366+ and CD8+DbPA224+ cells from the spleen and BAL (I, J). Data show mean ± SD for 4 (B6C3F1) or 5 (B6) mice. * p<0.05, **p<0.01 comparing parent with F1.

The CD62L lymph node homing receptor is typically down=regulated on influenza-virus specific CD8+ CTL effectors and reflects the extent of differentiation (40, 41). To determine whether levels of CD62L down-modulation were similar between B6 and F1 mice, we compared CD62L expression on CD8+ cells stained with DbNP366 and DbPA224 tetramers from B6 and B6C3F1 mice on day 8 after infection (Fig. 7I, J). The expression of CD62L on CD8+DbNP366+ cells from the spleen and BAL of B6 and B6C3F1 mice was similar. In contrast, significantly fewer T cells within the smaller CD8+DbPA224+ set from the spleens of B6C3F1 mice had down-modulated cell-surface CD62L by day 8 after infection (Fig. 7I) though, again, this effect was no longer apparent in the more highly stimulated BAL environment (Fig. 7J). Both high TNF-α prevalence (Fig. 7E–H) and the retention of the CD62Lhi phenotype (Fig. 7I) are, in fact, characteristic of T cells that have undergone less cycles of division during the course of the host response ((40, 42) and AE Denton, PC Doherty and SJ Turner unpublished observations). Thus, the diminished DbPA224-specific response may reflect an inability to fully differentiate a mature CTL response.

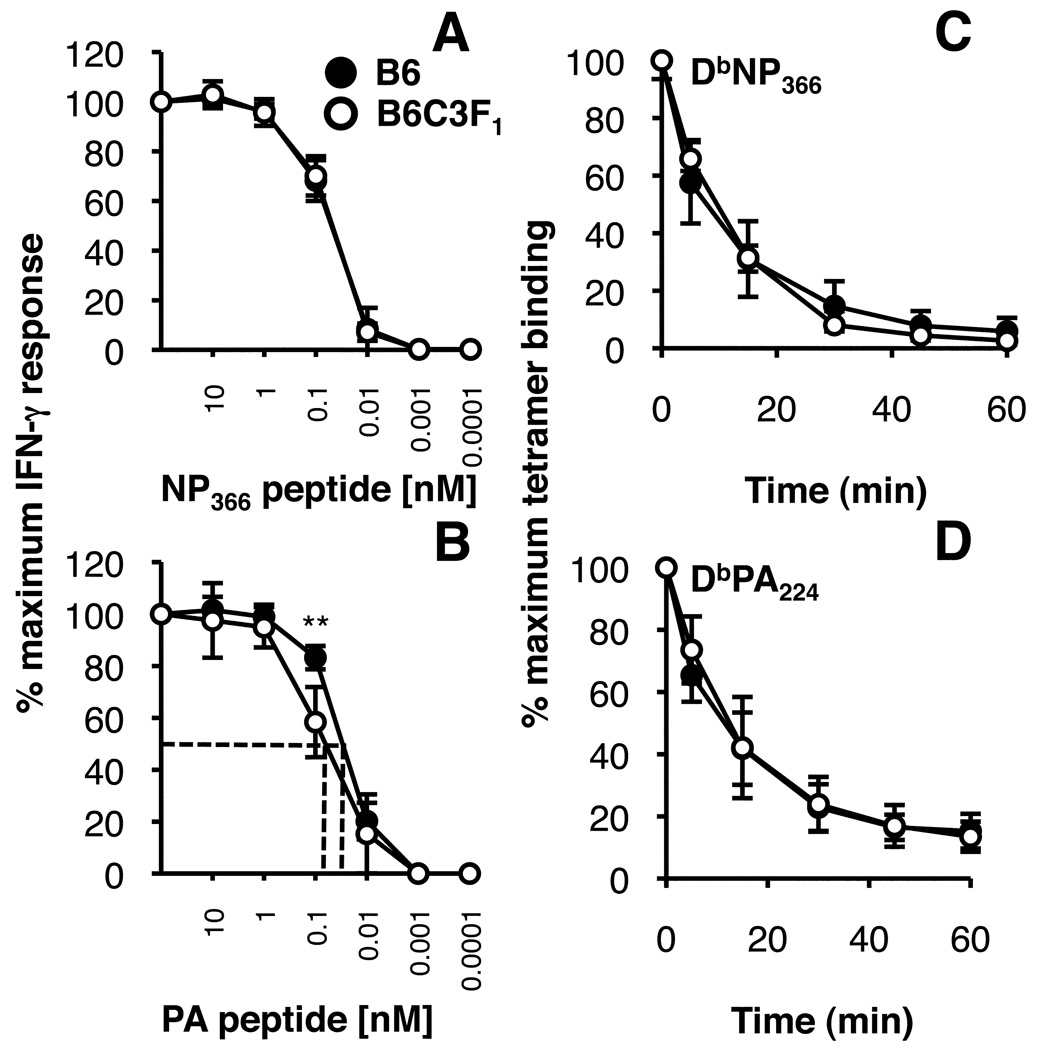

Functional avidity versus TCR/pMHC binding avidity

To determine whether differences in T cell responsiveness to peptide stimulation where involved in the impaired expansion of the F1 CD8+DbPA224+ set, immune CD8+DbNP366 and CD8+DbPA224+ cells were stimulated in vitro with graded concentrations of peptides, using IFN-g production as a read out (Fig. 8A, B). While identical profiles were found throughout for the B6 and F1 CD8+DbNP366+ sets (Fig 8A), the CD8+DbPA244+ T cells from B6C3F1 mice were slightly less sensitive at concentrations below 10−6 M (Fig. 8B). This variation in ‘functional avidity’ for the CD8+DbPA244+ T cells (Fig. 8B) was also independent of TCR avidity, as the rates of tetramer elution were identical (Fig. 8C, D) and the B6 and F1 TCR repertoire profiles look to be broadly comparable (Fig. 6 and Table I). Thus, the CD8+DbPA224+ cells from B6C3F1 mice are slightly less responsive to low concentrations of peptide, an effect which may, again, reflect that they have undergone fewer cycles of clonal expansion (43).

FIGURE 8.

Comparison of avidity profiles for influenza-specific CD8+ T cells from H2b and H2bxk F1 mice. Profiles of ‘functional avidity’ were determined for splenocytes from mice infected i.n. with the HKx31 virus 10 days previously. The T cells were stimulated with decreasing amounts (100 nM to 0.0001 nM) of NP366 (A) or PA224 (B) peptide for 5 h and the data is expressed as the percentage of IFN-g producing CD8+ cells with respect to the maximum IFN-g+CD8+ response following stimulation with the highest concentration of peptide. For measurement of TCR avidity by tetramer dissociation, splenocytes were stained with the DbNP366 (C) or DbPA224 (D) tetramers and incubated in the presence of anti-H2Db antibody at 37°C. The results show tetramer elution over time, represented as the percentage of cells staining with tetramer relative to maximum staining measured in the absence of the anti-H2Db blocking antibody. Mean ± SD for 5 mice. * p<0.05 comparing F1 and B6.

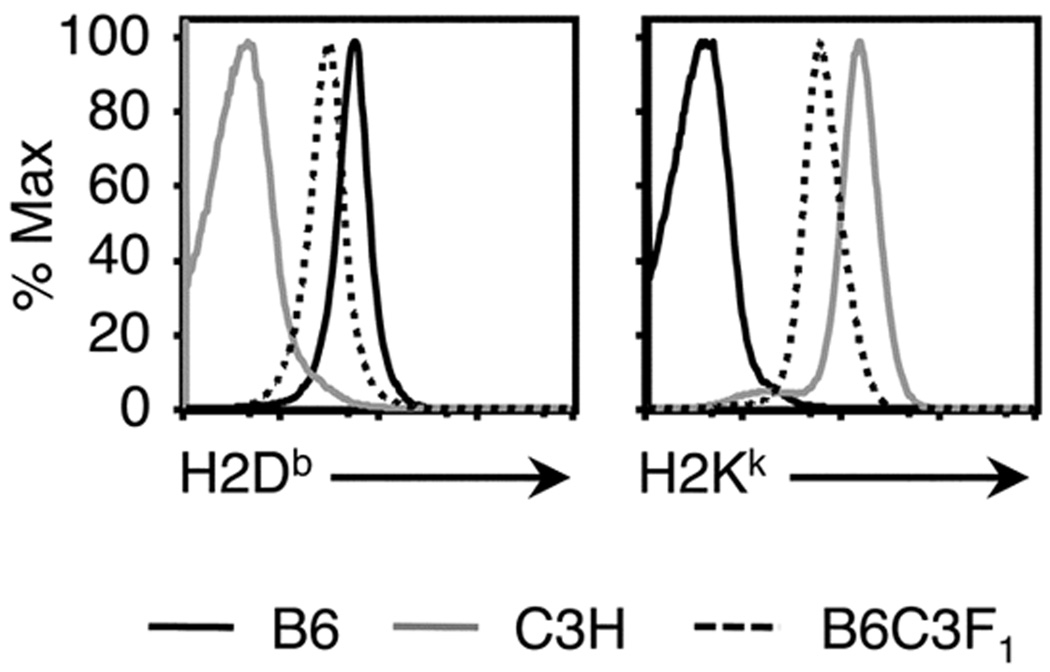

Reduced levels of MHCI allele expression may contribute to reduced responses in F1 mice

A way in which MHCI diversification in F1 mice may affect T cell priming is through altered levels of MHCI (and thus peptide) presentation. In fact, cell surface expression of H2Db and H2Kk was reduced in B6C3F1 mice with respect to parental mice (Fig. 8A). However, only the DbPA224-specific CTL response, and not the DbNP366-specific CTL response is substantially affected in F1 mice relative to B6 mice (Fig. 1A–D, Fig. 2A–D). This may reflect that DbPA224 presentation is more limited after influenza A virus infection (19, 44). If levels of antigen-presentation are a key determinant of response magnitude in F1 mice, then increasing levels of DbPA224 epitope presentation could potentially increase the magnitude of the CD8+ T cell response to this epitope in F1 mice. To test this hypothesis, we infected mice with a recombinant PR8-NAPA virus (19) that contains the PA224 peptide inserted into the neuraminidase stalk of the virus. This in turn increases the abundance of the PA224 peptide in the influenza virion and facilitates presentation of DbPA224 on non-professional APCs (19). In line with previous our previous findings, there was a modest increase in the percentage and number of DbPA224-specific CD8+ T cells in B6 mice (relative to mice that received a control virus) (Supplementary Fig 1A). However, the same increase in the DbPA224-specific response was not observed in F1 mice (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Thus, it appears that the ability to boost the DbPA224 response is limited by an intrinsic defect within the B6C3F1 background.

Discussion

The present analysis extends our earlier dissection of how H2k expression influences H2Db-restricted influenza-specific CD8+ CTL responses (3, 4). We demonstrated that H2bxk F1 mice generated reduced primary and memory CD8+ T cell responses to at least 4/5 H2Db- and H2Kb-restricted epitopes prominently recognised in the H2b parent. Moreover, the normal influenza CD8+ CTL immunodominance hierarchy established in the H2b (B6) mice was altered in the H2kxb (B6C3F1) heterozygotes due to a defect in the response to the DbPA224 epitope. These data demonstrate a broad effect of H2k expression on the magnitude of both immunodominant and subdominant responses. Importantly, reduced primary influenza-specific CTL responses in F1 mice could not be explained by reduced pulmonary virus titres. Numbers of DbNP366+ and DbPA224+ CLTps were reduced in B6C3F1 mice compared to B6 mice, an observation that could not be explained by deletion of a prominent TCRβ subset or noticeable differences in TCR CDR3β repertoire. This was unexpected given previous observations suggesting that CD8+DbPA224+Vβ7+ cells were missing from the B6C3F1 response (3). Immune CD8+DbNP366+ and CD8+DbPA224+ cells from B6C3F1 also seemed to be less differentiated and the CD8+DbPA224+ set was slightly less sensitive to stimulation with low concentrations of peptide. Together these data suggest that the F1 environment provides a lower quality of stimulation to these epitope-specific CD8+ T cells during infection, which contributes to functional and proliferative differences in these responses compared to the situation for the B6 parent.

The additional MHCI and genetic diversity of F1 mice can impact epitope-specific responses in two key ways: via differences in TCR repertoire selection that impact the availability of epitope-specific CTLps and through altered levels of epitope presentation. Although differences in the naive TCRVβ repertoire were found for B6 and B6C3F1 mice and seemed a likely explanation for the decrease in (particularly) DbPA224+ CTLp frequency, we were unable to identify defined ‘holes’ in the F1 repertoire that could account for this. Previous observations that the Vβ7+ subset of DbPA224-specific TCRs was missing in F1 mice (3) were most likely an artefact of using peptide-stimulated CTL lines, with consequent deletion or lack of expansion of these ‘high avidity’ TCR clonotypes in culture (30). It remains possible that, if we were to add the analysis of TCRα expression, we might find some evidence for deletion of F1 CD8+DbNP366 and CD8+DbPA224 clonotypes. However, apart from the fact that the numbers of naïve F1 CTLps are down by up to 2-fold, there is no a priori reason for thinking that this might be the case.

Interestingly, the mAb-defined profile of Vβ usage of CD8+ T cells from naïve B6C3F1 mice more closely resembled the Vβ repertoire selected in the C3H parent, rather than representing a mixture of B6 and C3H parental strains. Both MHC and non-MHC gene products are known to skew Vβ profiles in different mouse strains (45, 46) and, in this case, it seems that the C3H background (or H2k haplotype) is to some extent dominant. It is possible that, as a consequence of these differences in TCRβ repertoire selection, other epitope-specific responses found in B6 mice may be relatively diminished in the B6C3F1 heterozygotes. Indeed, further study will be needed to determine whether or not such a mechanism is responsible for the decreased responses to KbPB1703, DbPB1-F262 and KbNS2114 in B6C3F1 mice.

The effect of certain MHCI alleles on antigen-specific TCR usage has been shown for mice and humans. The HLA-B8 response to an epitope from the EBNA3 protein of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) (FLRGRAYGL, FL9) selects CD8+ cells expressing a public TCR (LC13) (47) that cross-reacts with the alloantigen HLA-B*4402 (48) and is deleted in HLA-B8+HLA-B*4402+ individuals (10). Even so, EBV-infected HLA-B8+B*4402+ individuals still mount a significant FL9-specific response, but utilize a different, more diverse spectrum of TCRs compared to HLA-B8+B*4402− individuals. These TCRs can avoid HLA-B*4402-reactivity by adopting a TCR footprint that is shifted to an area of polymorphism between HLA-B8 and HLA-B*4402 (49). Thus, the TCR repertoire has sufficient diversity and versatility to ensure that deletion of prominent antigen-specific TCR clonotypes does not severely compromise the magnitude of the response. In a study of vaccina virus infection of H2dxb F1 mice and inbred parents (5), altered epitope-specific TCRVβ profiles in the heterozygotes were not necessarily associated with diminished immune responses. Furthermore, the conservation of parental epitope-specific TCRVβ profiles in the F1 mice did not always result in equivalent response magnitudes. Thus, although expression of different MHCI alleles can lead to shifts in intrathymic selection of the TCR repertoire to maintain self-tolerance, this does not necessarily compromise the availability of epitope-specific TCRs or the response magnitude. However, contradicting this, a study of influenza-specific CTL responses in humans demonstrated that certain HLA-A- and HLA-B-restricted responses varied in magnitude depending on the HLA haplotype of the individual (9). While this highlights the significance of MHC-related effects on epitope-specific responses, it remains to be seen whether these effects are mediated at the level of thymic selection or antigen presentation.

The addition of MHCI alleles and background genes in F1 mice requires T cells with a greater range of MHCI-restriction and peptide-specificity to be accommodated without a change in overall CD8+ T cell numbers. The prevalence of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells may thus be reduced in F1 mice due to increased positive selection of other TCRs. Indeed, it has been suggested that lower levels of cell surface MHCI expression in heterozygous versus homozygous mice may play a role in reducing the positive selection of some epitope-specific TCRs (50), perhaps through a quantitative reduction in TCR signals (51). Differences in MHCI glycoprotein levels for cells from parental and F1 mice are in part a consequence of gene dosage (13). Analysis of cell surface H2Db and H2Kk concentrations on splenocytes from B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice showed reduced expression of both of these alleles in the F1 versus either parent. In this case, perhaps the decreased levels of H2Db result in reduced numbers of positively selected DbNP366+CD8+ and DbPA224+CD8+ cells and the observed decrease in naive CTLps.

It has been suggested that naïve precursor frequency can provide a good prediction of the immunodominance status of epitope-specific responses following antigen-driven clonal expansion (5, 36, 52). However, this relationship did not obviously determine the magnitude of DbNP366- and DbPA224-specific responses following influenza infection of B6 and B6C3F1 mice. In both strains, there are more naïve DbPA224+ CTLps compared to DbNP366+ CTLps yet, beyond the first few days, the DbPA224-specific response never dominates following normal influenza virus infection (53). Given the reduced H2Db expression in F1 mice, it is tempting to speculate that the levels of cell-surface DbNP366 and DbPA224 presentation may be selectively diminished in the F1, with consequent reduction in the quantity and quality of stimulation delivered to CD8+ T cells. However, any decrease in DbNP366 presentation does not appear to substantially affect relative response magnitudes in B6C3F1 versus B6 mice. This may reflect differences in the presentation profiles of DbNP366 and DbPA224. It has been demonstrated that during infection, a broader array of cell types are capable of presenting the DbNP366 epitope compared to the DbPA224 epitope during infection (20, 44). Thus, even though expression of H2Db is reduced in F1 compared to B6 mice, levels of DbNP366 presentation will likely be greater, and therefore sufficient, to prime a response in F1 mice similar in magnitude to that observed in B6 mice following primary infection. In contrast, the generally lower abundance of the PA protein coupled with reduced H2Db levels in B6C3F1 mice, may result in DbPA224 presentation that is decreased for both duration and concentration, with a consequent fall in clonal expansion and magnitude for responding CTL populations. In this way, a 2-fold lower precursor frequency could be extended to an 8-fold difference in numbers of splenic DbPA224+CD8+ T cells following primary infection. Interestingly, others have also found that relatively small differences in epitope-specific CTLp frequency between F1 mice and inbred parents can result in much larger differences in effector CTL numbers following infection or peptide vaccination (5). Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in DbPA224-specific response magnitude could reflect differences in antigen processing and presentation between B6C3F1 and B6 mice. It has been reported that presentation of the PA224 epitope is exquisitely sensitive to expression of specific immunoproteasome subunits (54). Thus, it remains a possibility that there is limited upregulation of immunoproteosome expression within the B6C3F1 mice that impacts PA224 processing and presentation. This intriguing possibility remains a possible avenue of future study.

Consistent with decreased proliferation and maturation of the response ((40, 42) and AE Denton, PC Doherty and SJ Turner unpublished observations), a greater proportion of CD8+DbPA224+ cells from B6C3F1 mice produced TNF-α (and in higher amounts) and more were CD62Lhi. Furthermore, despite equivalent structural TCR avidity, the B6C3F1 CD8+DbPA224+ population was slightly less sensitive to stimulation with peptide. Taken together, these data suggest that responses to DbPA224 are poorly elicited in the B6C3F1 environment and fail to reach their full potential for expansion and function. Indeed, several of the very early studies looking into the effect of MHC haplotype on virus-specific CTL responses suggested that the presence of an H2Kk environment during infection and not lack of precursors was responsible for limiting the potential of H2Db-restricted influenza-specific responses (4, 8).

As shown here, MHCI diversification can substantially affect the selection and expansion of many epitope-specific CD8+ T populations. The explanation of these effects is clearly not as simple as previously thought (3) and involves multiple factors that affect the generation of naïve precursors as well as the proliferation and activation of these precursors during infection. While this certainly presents challenges for the design of T cell-directed vaccines for use in MHCI-diverse human populations, these studies have provided key insights into the complexity of parameters that shape CTL response magnitude where MHCI diversification is apparent.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE 9.

Lower cell surface expression of H2Db and H2Kk on cells from B6C3F1 mice. Splenocytes from B6, C3H and B6C3F1 mice were treated to lyse erythrocytes and block Fc receptors, then stained separately with anti-H2Db-FITC and anti-H2Kk-FITC to measure cell surface MHCI expression. Histograms show staining intensities obtained for H2Db (A) and H2Kk (B) on total splenocyte populations from the three mouse strains. Histograms are scaled as a percentage of the peak response (% Max).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs AE Denton, MR Olson, K Kedzierska, J Stambas and BE Russ for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- aa

amino acid(s)

- BAL

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- d

day(s)

- EBV

Epstein-Barr virus

- HKx31

influenza virus A/HK-x31

- i.n.

intranasal

- h

hour(s)

- ICS

intracellular cytokine staining

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- MHCI

MHC class I

- pMHCI

peptide + MHC class I

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- NP50

influenza A virus nucleoprotein residues 50–57

- NP366

influenza A virus nucleoprotein residues 366–374

- NS2114

influenza A non-structural protein 2 residues 114–121

- PA224

influenza A acid polymerase residues 224–233

- PB1703

influenza A polymerase B1 residues 703–711

- PB1F262

influenza A polymerase B1 +1 reading frame residues 62–70

- PR8

influenza virus A/PR8/34

- pfu

plaque forming units

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

This work was supported by a NHMRC Dora Lush Postgraduate Scholarship (EBD), a Pfizer Senior Research Fellowship (S.J.T), a NHMRC RD Wright Fellowship (N.L.L), NHMRC program grant #5671222 (P.C.D, S.J.T), NHMRC grant #454595 (N.L.L) and NIH grant AI170251 (P.C.D).

References

- 1.Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunodominance in major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Anton LC, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Dissecting the multifactorial causes of immunodominance in class I-restricted T cell responses to viruses. Immunity. 2000;12:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belz GT, Stevenson PG, Doherty PC. Contemporary analysis of MHC-related immunodominance hierarchies in the CD8+ T cell response to influenza A viruses. J Immunol. 2000;165:2404–2409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty PC, Biddison WE, Bennink JR, Knowles BB. Cytotoxic T-cell responses in mice infected with influenza and vaccinia viruses vary in magnitude with H-2 genotype. J Exp Med. 1978;148:534–543. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.2.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flesch IE, Woo WP, Wang Y, Panchanathan V, Wong YC, La Gruta NL, Cukalac T, Tscharke DC. Altered CD8(+) T cell immunodominance after vaccinia virus infection and the naive repertoire in inbred and F(1) mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:45–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullbacher A, Blanden RV, Brenan M. Neonatal tolerance of major histocompatibility complex antigens alters Ir gene control of the cytotoxic T cell response to vaccinia virus. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1324–1338. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rai D, Pham NL, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Tracking the total CD8 T cell response to infection reveals substantial discordance in magnitude and kinetics between inbred and outbred hosts. J Immunol. 2009;183:7672–7681. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinkernagel RM, Althage A, Cooper S, Kreeb G, Klein PA, Sefton B, Flaherty L, Stimpfling J, Shreffler D, Klein J. Ir-genes in H-2 regulate generation of anti-viral cytotoxic T cells. Mapping to K or D and dominance of unresponsiveness. J Exp Med. 1978;148:592–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.2.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boon AC, de Mutsert G, Graus YM, Fouchier RA, Sintnicolaas K, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. The magnitude and specificity of influenza A virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in humans is related to HLA-A and -B phenotype. J Virol. 2002;76:582–590. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.582-590.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrows SR, Silins SL, Moss DJ, Khanna R, Misko IS, Argaet VP. T cell receptor repertoire for a viral epitope in humans is diversified by tolerance to a background major histocompatibility complex antigen. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1703–1715. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tussey LG, Rowland-Jones S, Zheng TS, Androlewicz MJ, Cresswell P, Frelinger JA, McMichael AJ. Different MHC class I alleles compete for presentation of overlapping viral epitopes. Immunity. 1995;3:65–77. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowland-Jones SL, Powis SH, Sutton J, Mockridge I, Gotch FM, Murray N, Hill AB, Rosenberg WM, Trowsdale J, McMichael AJ. An antigen processing polymorphism revealed by HLA-B8-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes which does not correlate with TAP gene polymorphism. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1999–2004. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tourdot S, Gould KG. Competition between MHC class I alleles for cell surface expression alters CTL responses to influenza A virus. J Immunol. 2002;169:5615–5621. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Neill HC. Quantitative variation in H-2-antigen expression. II. Evidence for a dominance pattern in H-2K and H-2D expression in F1 hybrid mice. Immunogenetics. 1980;11:241–254. doi: 10.1007/BF01567791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng H, Apple R, Clare-Salzler M, Trembleau S, Mathis D, Adorini L, Sercarz E. Determinant capture as a possible mechanism of protection afforded by major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in autoimmune disease. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1675–1680. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messaoudi I, Guevara Patino JA, Dyall R, LeMaoult J, Nikolich-Zugich J. Direct link between mhc polymorphism, T cell avidity, and diversity in immune defense. Science. 2002;298:1797–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.1076064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Price DA, West SM, Betts MR, Ruff LE, Brenchley JM, Ambrozak DR, Edghill-Smith Y, Kuroda MJ, Bogdan D, Kunstman K, Letvin NL, Franchini G, Wolinsky SM, Koup RA, Douek DC. T cell receptor recognition motifs govern immune escape patterns in acute SIV infection. Immunity. 2004;21:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Correia-Neves M, Waltzinger C, Mathis D, Benoist C. The shaping of the T cell repertoire. Immunity. 2001;14:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Pang K, Webby R, Davenport M, Chen W, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. A virus-specific CD8+ T cell immunodominance hierarchy determined by antigen dose and precursor frequencies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:994–999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510429103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webby RJ, Andreansky S, Stambas J, Rehg JE, Webster RG, Doherty PC, Turner SJ. Protection and compensation in the influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7235–7240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232449100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tannock GA, Paul JA, Barry RD. Relative immunogenicity of the cold-adapted influenza virus A/Ann Arbor/6/60 (A/AA/6/60-ca), recombinants of A/AA/6/60-ca, and parental strains with similar surface antigens. Infect Immun. 1984;43:457–462. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.457-462.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kedzierska K, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. Conserved T cell receptor usage in primary and recall responses to an immunodominant influenza virus nucleoprotein epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4942–4947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401279101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner SJ, Diaz G, Cross R, Doherty PC. Analysis of clonotype distribution and persistence for an influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Immunity. 2003;18:549–559. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arden B, Clark SP, Kabelitz D, Mak TW. Mouse T-cell receptor variable gene segment families. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:501–530. doi: 10.1007/BF00172177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moon JJ, Chu HH, Pepper M, McSorley SJ, Jameson SC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK. Naive CD4(+) T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.La Gruta NL, Rothwell WT, Cukalac T, Swan NG, Valkenburg SA, Kedzierska K, Thomas PG, Doherty PC, Turner SJ. Primary CTL response magnitude in mice is determined by the extent of naive T cell recruitment and subsequent clonal expansion. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1885–1894. doi: 10.1172/JCI41538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Townsend AR, Rothbard J, Gotch FM, Bahadur G, Wraith D, McMichael AJ. The epitopes of influenza nucleoprotein recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes can be defined with short synthetic peptides. Cell. 1986;44:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Belz GT, Xie W, Altman JD, Doherty PC. A previously unrecognized H-2D(b)-restricted peptide prominent in the primary influenza A virus-specific CD8(+) T-cell response is much less apparent following secondary challenge. J Virol. 2000;74:3486–3493. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3486-3493.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastin J, Rothbard J, Davey J, Jones I, Townsend A. Use of synthetic peptides of influenza nucleoprotein to define epitopes recognized by class I-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1508–1523. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.6.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.La Gruta NL, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. Hierarchies in cytokine expression profiles for acute and resolving influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses: correlation of cytokine profile and TCR avidity. J Immunol. 2004;172:5553–5560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gould KG, Scotney H, Brownlee GG. Characterization of two distinct major histocompatibility complex class I Kk-restricted T-cell epitopes within the influenza A/PR/8/34 virus hemagglutinin. J Virol. 1991;65:5401–5409. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5401-5409.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doherty PC, Zinkernagel RM. Enhanced immunological surveillance in mice heterozygous at the H-2 gene complex. Nature. 1975;256:50–52. doi: 10.1038/256050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branger J, Knapp S, Weijer S, Leemans JC, Pater JM, Speelman P, Florquin S, van der Poll T. Role of Toll-like receptor 4 in gram-positive and gram-negative pneumonia in mice. Infect Immun. 2004;72:788–794. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.788-794.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ely KH, Cauley LS, Roberts AD, Brennan JW, Cookenham T, Woodland DL. Nonspecific recruitment of memory CD8+ T cells to the lung airways during respiratory virus infections. J Immunol. 2003;170:1423–1429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obar JJ, Khanna KM, Lefrancois L. Endogenous naive CD8+ T cell precursor frequency regulates primary and memory responses to infection. Immunity. 2008;28:859–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dyall R, Messaoudi I, Janetzki S, Nikolic-Zugic J. MHC polymorphism can enrich the T cell repertoire of the species by shifts in intrathymic selection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1695–1698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deckhut AM, Allan W, McMickle A, Eichelberger M, Blackman MA, Doherty PC, Woodland DL. Prominent usage of V beta 8.3 T cells in the H-2Db-restricted response to an influenza A virus nucleoprotein epitope. J Immunol. 1993;151:2658–2666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turner SJ, Kedzierska K, Komodromou H, La Gruta NL, Dunstone MA, Webb AI, Webby R, Walden H, Xie W, McCluskey J, Purcell AW, Rossjohn J, Doherty PC. Lack of prominent peptide-major histocompatibility complex features limits repertoire diversity in virus-specific CD8+ T cell populations. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:382–389. doi: 10.1038/ni1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badovinac VP, Haring JS, Harty JT. Initial T cell receptor transgenic cell precursor frequency dictates critical aspects of the CD8(+) T cell response to infection. Immunity. 2007;26:827–841. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kedzierska K, Venturi V, Field K, Davenport MP, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. Early establishment of diverse T cell receptor profiles for influenza-specific CD8(+)CD62L(hi) memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9184–9189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603289103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kedzierska K, Stambas J, Jenkins MR, Keating R, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. Location rather than CD62L phenotype is critical in the early establishment of influenza-specific CD8+ T cell memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Functional avidity maturation of CD8(+) T cells without selection of higher affinity TCR. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:711–717. doi: 10.1038/90650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crowe SR, Turner SJ, Miller SC, Roberts AD, Rappolo RA, Doherty PC, Ely KH, Woodland DL. Differential antigen presentation regulates the changing patterns of CD8+ T cell immunodominance in primary and secondary influenza virus infections. J Exp Med. 2003;198:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vacchio MS, Hodes RJ. Selective decreases in T cell receptor V beta expression. Decreased expression of specific V beta families is associated with expression of multiple MHC and non-MHC gene products. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1335–1346. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bill J, Kanagawa O, Woodland DL, Palmer E. The MHC molecule I-E is necessary but not sufficient for the clonal deletion of V beta 11-bearing T cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1405–1419. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.4.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Argaet VP, Schmidt CW, Burrows SR, Silins SL, Kurilla MG, Doolan DL, Suhrbier A, Moss DJ, Kieff E, Sculley TB, Misko IS. Dominant selection of an invariant T cell antigen receptor in response to persistent infection by Epstein-Barr virus. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2335–2340. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burrows SR, Khanna R, Burrows JM, Moss DJ. An alloresponse in humans is dominated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) cross-reactive with a single Epstein-Barr virus CTL epitope: implications for graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1155–1161. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gras S, Burrows SR, Kjer-Nielsen L, Clements CS, Liu YC, Sullivan LC, Bell MJ, Brooks AG, Purcell AW, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. The shaping of T cell receptor recognition by self-tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinic MM, Rocha B, McCoy KD, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Role of TCR-restricting MHC density and thymic environment on selection and survival of cells expressing low-affinity T cell receptors. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1041–1049. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe N, Arase H, Onodera M, Ohashi PS, Saito T. The quantity of TCR signal determines positive selection and lineage commitment of T cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:6252–6261. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kotturi MF, Scott I, Wolfe T, Peters B, Sidney J, Cheroutre H, von Herrath MG, Buchmeier MJ, Grey H, Sette A. Naive precursor frequencies and MHC binding rather than the degree of epitope diversity shape CD8+ T cell immunodominance. J Immunol. 2008;181:2124–2133. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kedzierska K, Day EB, Pi J, Heard SB, Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Perlman S. Quantification of repertoire diversity of influenza-specific epitopes with predominant public or private TCR usage. J Immunol. 2006;177:6705–6712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pang KC, Sanders MT, Monaco JJ, Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Chen W. Immunoproteasome subunit deficiencies impact differentially on two immunodominant influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2006;177:7680–7688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.