Abstract

AIM: To assess the long-term outcome of endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation (EHL) for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

METHODS: A total of 759 consecutive patients (415 males and 344 females) were enrolled. Clinical presentations were rectal bleeding (593 patients) and mucosal prolapse (166 patients). All patients received EHL at outpatient clinics. Hemorrhoid severity was classified by Goligher’s grading. The mean follow-up period was 55.4 mo (range, 45-92 mo).

RESULTS: The number of band ligations averaged 2.35 in the first session for bleeding and 2.69 for prolapsed patients. Bleeding was controlled in 587 (98.0%) patients, while prolapse was reduced in 137 (82.5%) patients. After treatment, 93 patients experienced anal pain and 48 patients had mild bleeding. Patient subjective satisfaction was 93.6%. Repeat treatment or surgery was performed if symptoms were not relieved in the first session. In the bleeding group, the recurrence rate was 3.7% (22 patients) at 1 year, and 6.6% and 13.0% at 2 and 5 years. In the prolapsed group, the recurrence rate was 3.0%, 9.6% and 16.9% at 1, 2 and 5 years, respectively.

CONCLUSION: EHL is an easy and well-tolerated procedure for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids, with good long-term results.

Keywords: Bleeding, Endoscopy, Hemorrhoid, Ligation, Prolapsed

INTRODUCTION

Hemorrhoids are the most prevalent anorectal disorder among adults, and over 90% of patients undergoing sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy are found to have hemorrhoids of varying degrees. Hemorrhoids are defined as internal or external based on whether they are located above or below the dentate line. Internal hemorrhoids can be classified into 4 grades using the Goligher system[1]: Grade 1, hemorrhoids with bleeding; Grade 2, hemorrhoids with bleeding and protrusion, with spontaneous reduction; Grade 3, hemorrhoids with bleeding and protrusion that require manual reduction; and Grade 4, prolapsed hemorrhoids that cannot be replaced. Nonoperative management is considered for patients with symptoms (anal bleeding or rectal prolapse) and grades 1, 2, and 3 internal hemorrhoids. Treatments include local injection therapy, anal divulsion, elastic band ligation, cryotherapy, infrared and laser photocoagulation, direct application of electrical current, and bipolar coagulation[2,3]. Based on the results of a meta-analysis, MacRae and McLeod[4] concluded that rubber band ligation should be recommended for Grades 1 to 3 internal hemorrhoids, and that patients treated by this method were less likely to require additional therapies than those treated with local injection therapy or infrared coagulation.

Since first introduced in the United States in 1951, rubber band ligation has become the mainstay of treatment for bleeding and prolapsing internal hemorrhoids, and is now a well-established, safe, and effective technique[5-7]. It has been shown to be substantially better than medication alone in terms of outcome, and is not associated with significant morbidity[8]. Conventional band ligation is performed with rigid anoscopic devices with limited maneuverability and a narrow field of view, and no ability to document treatment photographically[4]. These drawbacks can be overcome by using a video-endoscopic system that provides a detailed image of the operative field as well as photographic capability[9]. Our previous studies showed a good result of endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation (EHL) in patients with symptomatic internal hemorrhoids at initial therapy and one year after treatment[10,11]. The aim of this study was to further assess the long-term outcome and efficacy of EHL for treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From November 2000 to October 2004, 759 consecutive patients with symptomatic internal hemorrhoids were treated with EHL and enrolled in this study prospectively. All the procedures were performed by the same endoscopist who has more than 10 years of endoscopic surgery experience. Before EHL, the endoscopist needs to identify the dentate line, and then EHL is easy to perform without learning curve. The whole procedure takes about 2-3 min, and compared to the traditional technique by anosocpe, EHL offers good view and also recordable for the trainee to learn the procedure.

There are 415 male and 344 female patients with a mean age of 54.2 years (range, 18-92 years). Rectal bleeding or prolapse was the major patient complaints. Sixty-eight patients were cirrhotic and 36 patients were uremia.

All patients underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy after fleet enema 1pc or colonoscopy after standard colonic preparation with polyethylene glycol 2000 mL or sodium phosphate 90 mL in splitting doses to exclude other causes of rectal bleeding. Patients were excluded if polyps or evidence of malignancy was found at colonoscopy. All patients gave informed consent for the ligation procedure. Patients were not asked to discontinue the use of aspirin or other non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) before the procedures. The contraindications of EHL were the same as traditional band ligation, such as thrombosed hemorrhoids, anal fistula or peri-anal abscess.

After the initial endoscopic examination, patients were treated if Grade 2 or greater internal hemorrhoids were present. As with esophageal variceal ligation, a transparent plastic endoscopic ligation cap (Sumitomo Co., Tokyo, Japan) was attached to the top of a diagnostic upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscope (GIF-XQ230; Olympus Optical Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). The dentate line then was identified, and ligation was performed 2-5 mm above the dentate line (Figure 1). The hemorrhoid was suctioned into the cap with the tip of the endoscope in the anal canal, and a single elastic band was released. If further ligation was required, another rubber band was placed on the cap. All ligations were performed in an outpatient setting without any premedications such as sedatives or analgesics.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of internal hemorrhoid, 2-5 mm above the dentate line, ligated with a rubber band.

Safety data were recorded and all adverse events were documented. After first treatment session, patients were asked to complete a questionnaire to evaluate the subjective satisfaction, which was classified as excellent, good, fair or poor. Patients were seen 1 wk after the procedure and then monthly and sigmoidoscopy after fleet enema 1pc was performed at all visits. In all cases, hemorrhoid severity and recurrent symptoms were assessed yearly after the ligation session. Failure of treatment was defined as persisted symptoms beginning 1 mo after ligation. Recurrent bleeding was defined as anal bleeding with two separate bowel movements or massive bleeding that required further treatment after one month of ligation. Recurrent prolapse was defined as recurrent prolapse symptoms that were troublesome to patient lasting more than 2 mo after initial successful treatment and requiring further treatment.

Student t test was used for analysis and P value less than 0.05 defined as statistically significant.

RESULTS

All patients were treated with one session initially, and were followed regularly. The mean follow-up period was 55.4 mo (range, 45-92 mo). Overall patient satisfaction was 93.6% after the first treatment session.

Rectal bleeding was the chief complaint of 593 patients: 146 had anemia (hemoglobin < 12 g/dL) due to hemorrhoid bleeding; 273 experienced intermittent dripping of blood from the anal area; and 174 noted blood intermittently on toilet tissue. Rectal bleeding was controlled in 587 patients (98.0%). The average number of band ligations performed in the first session for rectal bleeding was 2.35. There were 6 patients in whom symptoms were not controlled in the first session, and received a second treatment session. Bleeding in these patients was controlled after second session, thus, all of the patients had their symptoms controlled. The recurrence rate was 3.7% at 1 year (22 patients), 6.6% at 2 years, and 13.0% at 5 years.

Rectal prolapse requiring manual reduction was the major complaint of 166 of the 759 patients, 131 of whom also had intermittent mild rectal bleeding. The severity of hemorrhoid prolapse was classified by Goligher’s grading. Most patients (82.5%, 137/166) had their hemorrhoids reduced by at least one grade in the first session (Table 1). Figures 2 and 3 showed improvement of pre- and post-treatment of ligation for Grade 4 hemorrhoids. The average number of band ligations performed in the first session was 2.69. For failed control of symptoms in the first session, 4 patients received further surgical hemorrhoidectomy due to thrombosed hemorrhoids and perianal abscess, while 21 patients received the second session of whom 17 had their symptom controlled. Three patients received a third EHL session and 2 patients showed improvement while the other received a hemorrhoidectomy for poor response to EHL. Five patients in the prolapsed group were lost to follow-up. The recurrence rate at 1 year was 3.0% (5 patients), at 2 years was 9.6%, and at 5 years was 16.9% (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Severity of hemorrhoids in the prolapsed group before and after the first endoscopic ligation session

| Before treatment | After treatment | |||

| Goligher grade | IV | 23 | IV | 7 |

| III | 16 | |||

| III | 130 | III | 22 | |

| II | 93 | |||

| I | 15 | |||

| II | 13 | I | 13 | |

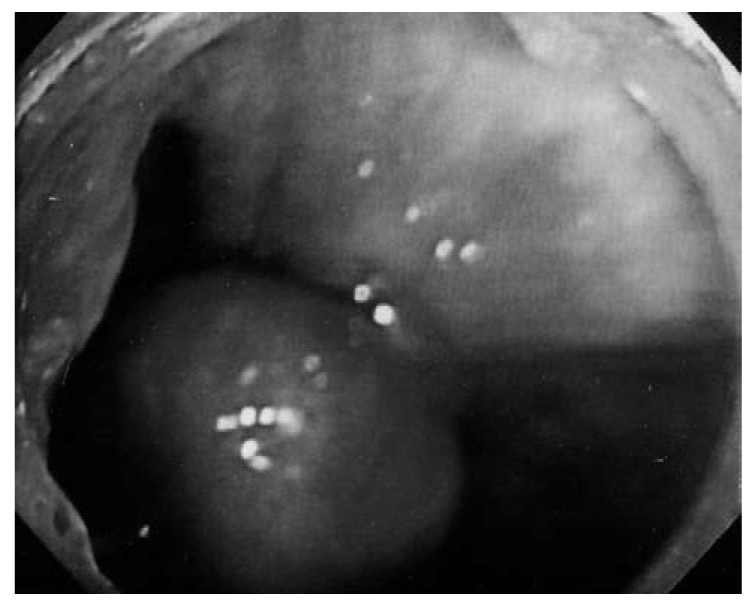

Figure 2.

Pre-treatment showed grade 4 hemorrhoids.

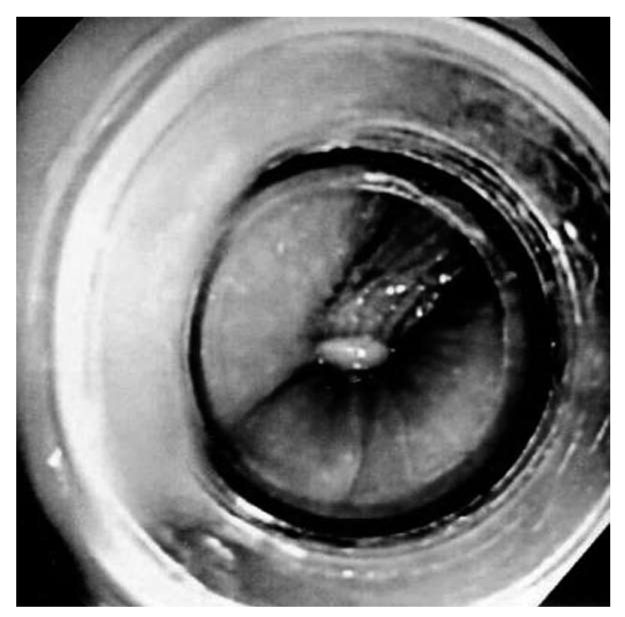

Figure 3.

After ligation, grade 4 hemorrhoids showed spontaneous reduction.

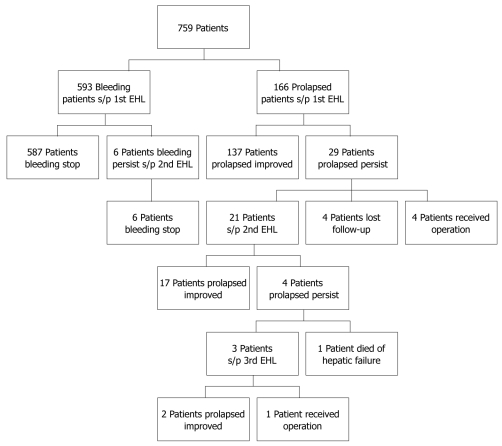

Figure 4.

Outcomes of the 759 patients undergoing endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation. EHL: Endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation.

The symptom control rate was higher in the bleeding group than in the prolapsed group (98.0% vs 82.5%, respectively; P = 0.043). A total of 93 patients (12.3%) experienced mild anal pain or tenesmus sensation 1-3 days after treatment, which was relieved by oral mefenamic acid. There were 48 patients (6.3%) who had mild bleeding 1-14 d after ligation (mild bleeding means some blood noted in tissue papers), and most of them were treated by injection of 1-3 mL diluted solution of epinephrine (1:100 000) in divided doses directly into the wound. Two cirrhotic patients had experienced massive bleeding due to post-ligation ulcers (Figure 5) and required blood transfusion. Bleeding was controlled with local injection of epinephrine. No EHL-related mortality was observed.

Figure 5.

Ulcer formation after ligation.

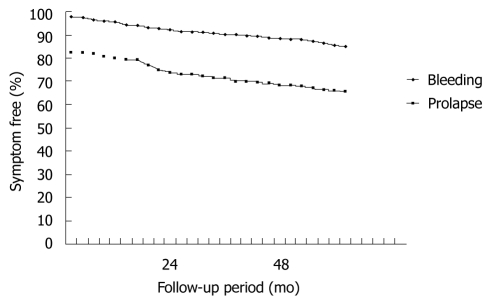

The patients’ subjective satisfaction was 93.6% (excellent or good response) after the first treatment session. The mean follow-up period was 55.4 mo (range, 45-92 mo). The percentage of symptom free patients during follow-up period is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Five-year follow-up for the symptom-free percentage of bleeding and prolapsed patients.

DISCUSSION

Rubber band ligation has been used to treat internal hemorrhoids since Blaisdale introduced a ligation device in 1951. This device is used via an anoscope to grasp hemorrhoid tissue with small prongs and an elastic band is applied. The hemorrhoid and its redundant mucosal tissues become thrombosed and slough off, usually within 5-7 d. One notable advantage of band ligation is the production of submucosal scarring that prevents subsequent development of new hemorrhoid tissue. Rubber band ligation is technically simple and can be used in the outpatient setting without local anesthesia. The reported success rate varies between 69% and 97%, depending on the degree of internal hemorrhoids, the ligation technique, and the duration of follow-up[8]. Serious complications, such as life-threatening massive bleeding[12,13] and sepsis are extremely rare, but should not be discounted[14,15]. Dickey and Garrett[16] found that hemorrhoid banding using video-endoscopic anoscopy and a single-handed ligator compared favorably with traditional hemorrhoid banding by anoscopy. This video-endoscopic technique may be preferred in the office setting.

There are other several non-operative methods for management of internal hemorrhoids, such as sclerotherapy, cryotherapy, direct-current electrotherapy and infrared photocoagulation. MacRae et al performed a meta-analysis covering 23 studies that compared rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, hemorrhoidectomy, infrared photocoagulation, and manual dilation of the anus for patients with Grade 1-3 hemorrhoids[17]. They found that rubber band ligation was more effective than sclerotherapy, less likely to require additional therapy than either infrared photocoagulation or sclerotherapy, and more likely to cause pain.

Stiegmann and Goff[18] first proposed elastic band ligation for the treatment of esophageal and gastric varices using a device attached to the tip of a video-endoscope to deploy the bands. Endoscopic band ligation of esophageal varices now is preferred to sclerotherapy because of equivalent efficacy, ease of use, and relatively fewer complications[19,20]. The application of the same device and technique to eradicate internal hemorrhoids is a logical extension of this established procedure. Trowers et al[9] reported preliminary experience with endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation in 1997 in which 95% of internal hemorrhoids were reduced by more than one grade after treatment. Berkelhammer and Moosvi[21] used retroflexed endoscopic band ligation to treat bleeding internal hemorrhoids. Excellent results were achieved in 80% of patients with Grade 2 hemorrhoids. In addition, the results with treatment of patients with Grade 2 hemorrhoids were more likely to be excellent compared with those for patients with Grade 3 hemorrhoids.

There are two different endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation devices, a smaller one that is attached to gastroscope just as variceal ligators, and a larger one with a greater diameter cap used with a colonoscope. Our previous study showed that these two devices provided similar good results for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids[10]. A later study in which the variceal ligation device was used with a gastroscope showed good initial and one-year results with more than 90% of hemorrhoids reduced by at least one grade[11].

In this study, we used the gastroscope for hemorrhoid ligation and found that 82.5% (137/166) of patients had their hemorrhoids reduced by at least one grade in the first session, with 93.6% subjective satisfaction. In addition, more than 80% of patients had sustained results. The symptom control rate was better in bleeding group other than prolapsed group. Bleeding hemorrhoids were easily identified by endoscopic view, while the prolapsed loosen hemorrhoid tissue might need more bands ligated to induce adequate submucosal fibrosis which would make the prolapsed tissue fixed in rectum. Only minor complications occurred such as mild anal bleeding and pain, and only 5 patients required further surgical interventions. Two cirrhotic patients had experienced massive bleeding due to post-ligation ulcers but the bleeding was controlled with local injection of epinephrine solution. Because cirrhotic or uremia patients were risky for bleeding tendency, these patients were at a higher risk for operation, EHL provided an alternative therapy for hemorrhoids of these patients and the risk was low compared with operation. The greatest advantage of EHL is that it can be performed repeatedly if needed. Patients who failed in symptom control after their first EHL session treatment received further treatment sessions, and most patients had good results. After successful treatment, the one-year recurrent rate was 3.7% in bleeding group and 3.0% in prolapsed group and the five-year recurrent rate was 13.0% in bleeding group and 16.9% in prolapsed group.

In conclusion, endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation is an important progress in the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation is simple, safe, and effective. Multiple bands can be applied in one session, and further bands can be applied in subsequent sessions if a single session fails to completely eradicate the internal hemorrhoids. The treatment success rate is high, and the long-term recurrence rate is low.

COMMENTS

Background

Previous studies showed a good result of endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation (EHL) in patients with symptomatic internal hemorrhoids at initial therapy and one year after treatment.

Research frontiers

The aim of this study was to further assess the long-term outcome and efficacy of EHL for treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation is an important advance in the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Endoscopic hemorrhoid ligation is simple, safe, and effective. Multiple bands can be applied in one session, and further bands can be applied in subsequent sessions if a single session fails to completely eradicate the internal hemorrhoids. The treatment success rate is high, and the long-term recurrence rate is low.

Applications

EHL is an easy and well-tolerated procedure for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids, with good long-term results.

Terminology

EHL means endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation, which is a new device of rubber band ligation for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

Peer review

This is a well written and comprehensive report characterizing a substantive cohort in endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation for the treatment of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Mitsuhiro Fujishiro, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan; John Marshall, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Missouri School of Medicine, Columbia, MO 65201, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Schrock TR. Hemorrhoids: nonoperative and interventional management. In: Barkin J, O’Phelan CA, editors. Advanced therapeutic endoscopy. New York: Raven Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfenninger JL, Surrell J. Nonsurgical treatment options for internal hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 1995;52:821–834, 839-841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salvati EP. Nonoperative management of hemorrhoids: evolution of the office management of hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:989–993. doi: 10.1007/BF02236687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatment modalities. A meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:687–694. doi: 10.1007/BF02048023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BLAISDELL PC. Office ligation of internal hemorrhoids. Am J Surg. 1958;96:401–404. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(58)90933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.BARRON J. Office ligation of internal hemorrhoids. Am J Surg. 1963;105:563–570. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(63)90332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatments: a meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 1997;40:14–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen SL, Harling H, Arseth-hansen P, Tange G. The natural history of symptomatic haemorrhoids. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:41–44. doi: 10.1007/BF01648549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trowers EA, Ganga U, Rizk R, Ojo E, Hodges D. Endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation: preliminary clinical experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su MY, Tung SY, Wu CS, Sheen IS, Chen PC, Chiu CT. Long-term results of endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation: two different devices with similar results. Endoscopy. 2003;35:416–420. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su MY, Chiu CT, Wu CS, Ho YP, Lien JM, Tung SY, Chen PC. Endoscopic hemorrhoidal ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:871–874. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(03)02308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odelowo OO, Mekasha G, Johnson MA. Massive life-threatening lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage following hemorrhoidal rubber band ligation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:1089–1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bat L, Melzer E, Koler M, Dreznick Z, Shemesh E. Complications of rubber band ligation of symptomatic internal hemorrhoids. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:287–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02053512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quevedo-Bonilla G, Farkas AM, Abcarian H, Hambrick E, Orsay CP. Septic complications of hemorrhoidal banding. Arch Surg. 1988;123:650–651. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400290136024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell TR, Donohue JH. Hemorrhoidal banding. A warning. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:291–293. doi: 10.1007/BF02560424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickey W, Garrett D. Hemorrhoid banding using videoendoscopic anoscopy and a single-handed ligator: an effective, inexpensive alternative to endoscopic band ligation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1714–1716. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macrae HM, Temple LK, Mcleod RS. A meta-analysis of hemorrhoidal treatments. Semin C R Surg. 2002;13:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Stiegmann G, Goff JS. Endoscopic esophageal varix ligation: preliminary clinical experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(88)71274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks RD, Arnold MD, Baron TH. Gross and microscopic findings in the human esophagus after esophageal variceal band ligation: a postmortem analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:272–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young MF, Sanowski RA, Rasche R. Comparison and characterization of ulcerations induced by endoscopic ligation of esophageal varices versus endoscopic sclerotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(93)70049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berkelhammer C, Moosvi SB. Retroflexed endoscopic band ligation of bleeding internal hemorrhoids. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:532–537. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]