Abstract

Using a model of established malignancy, we found that cyclophosphamide (Cy), administered at a dose not requiring hematopoietic stem cell support, is superior to low-dose total body irradiation in augmenting antitumor immunity. We observed that Cy administration resulted in expansion of tumor antigen-specific T cells and transient depletion of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs). The antitumor efficacy of Cy was not improved by administration of anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody given to induce more profound Treg depletion. We found that Cy, through its myelosuppressive action, induced rebound myelopoiesis and perturbed dendritic cell (DC) homeostasis. The resulting DC turnover led to the emergence of tumor-infiltrating DCs that secreted more IL-12 and less IL-10 compared to those from untreated tumor-bearing animals. These newly recruited DCs, originating from proliferating early DC progenitors, were fully capable of priming T cell responses and ineffective in inducing expansion of Tregs. Together, our results show that Cy-mediated antitumor effects extend beyond the well-documented cytotoxicity and lymphodepletion and include resetting the DC homeostasis, thus providing an excellent platform for integration with other immunotherapeutic strategies.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-009-0734-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Nonmyeloablative chemotherapy, Dendritic cells, Hematopoietic stem cells, Antitumor immunity

Introduction

In recent years, several studies have suggested that chemotherapy and radiotherapy administered in nonmyeloablative doses may augment the host’s immune response to malignancy, especially if given in sequence with other immunotherapeutic modalities [1, 2]. This effect is thought to be a consequence of chemoradiotherapy-mediated enhanced tumor-cell apoptosis and cross-presentation of tumor antigens [3, 4], elimination of cytokine sinks [5], augmented homeostasis-driven expansion of tumor-induced or adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [6, 7], depletion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) [7–9], and destruction of tumor stroma [10]. Use of myeloablative irradiation as a platform for adoptive transfer of tumor-specific T cells has also provided insight into additional mechanisms that can augment antitumor activity. First, irradiation-induced tissue injury associated with release of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines and translocation of bacteria-derived LPS into bloodstream provides a milieu that is optimal for in vivo activation of dendritic cells (DCs) [11]. Second, purified hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) given primarily to rescue myeloablated host can directly stimulate expansion of adoptively transferred T cells [12]. This effect is presumably related to the ability of transferred Lin−CD117+ HSCs to rapidly differentiate into antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in vivo. Recent study showed comparable antitumor benefits of nonmyeloablative and myeloablative conditioning with total body irradiation (TBI) as a platform for adoptive cell therapy [13]. We hypothesized that alternative strategy which could bypass the obstacles of high toxicity and complexity of ex vivo cell manipulation, while relying on the same mechanisms in augmenting antitumor immunity would be advantageous for clinical translation.

Cyclophosphamide (Cy) is different from majority of other chemotherapeutic agents in that it can be repeatedly administered in very high doses without the need for HSC rescue due to the lack of toxicity to stem cells [14, 15]. Cy treatment is known to modulate both adaptive and innate immunity. On the T cell side, Cy administration induces transient lymphopenia that is associated with augmented in vivo proliferation and expansion of antigen-specific T cells [16], reduction in the number of Tregs [7, 9, 17], and augmented function of tumor-infiltrating T cells in the tumor stroma [18]. Cy effects on the innate immunity are manifested through increased levels of type I IFN and other proinflammatory cytokines in serum [16, 19] and by elevated number and activation status of CD11b+ myeloid cells in vivo [16, 20, 21]. We thus sought to further examine the mechanisms of Cy-augmented antitumor immunity, particularly those pertaining to T cell–DC interaction in vivo.

Here, using a model of advanced metastatic disease, we report that Cy administration provides strong antitumor effect resulting in survival of approximately 40% of animals. We found that, despite Cy’s well-described effects on Treg elimination, Tregs recover rapidly and further attempts to prolong their depletion yield no additional benefit. We found that Cy’s effect of inducing reversal of systemic and in situ DC paralysis in the tumor-bearing hosts and its ability to mobilize early proliferating DC progenitors are crucial mechanisms for enhancing antitumor immunity.

Materials and methods

Animals

BALB/cAnNCr (BALB/c; H-2d, CD45.2) and C57BL/6 (B6; H-2b) mice were purchased from NCI (Frederick, MD, USA). BALB/c-CD45.1 and BALB/c-Ifngtm1Ts (IFN-γKO) mice were maintained in a pathogen-free facility and were 6–8 weeks old at the time of experiments. All experiments were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University.

Cell lines and tumor model

CT26 colon carcinoma (H-2d) cell line was maintained as previously described [22, 23]. For tumor implantation, we employed the model of hemispleen injection previously described [23]. On day 13 after tumor implantation, animals were injected intraperitoneally with 200 mg/kg of cyclophosphamide (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Evansville, IN, USA). In designated experiments animals were irradiated with 200 cGy on day 10 post-tumor implantation. For in vivo CD4, CD8, or CD25 depletion, tumor-bearing animals were injected intraperitoneally with designated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or corresponding isotype control at a dose and schedule indicated for each individual experiment. Following clones were used: GK1.5 (anti-CD4), 2.43 (anti-CD8), and PC61 (anti-CD25). All antibodies were obtained from BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH, USA. On day 16, post-tumor implantation a tumor vaccine comprised of irradiated (5,000 cGy) 106 CT26 tumor cells and 5 × 105 GM-CSF secreting B78H1 cells (bystander) (2:1 ratio) was injected subcutaneously in the hind region [22].

Cell preparation and CD11c+ isolation from liver and spleen

Livers were processed for isolation and mononuclear infiltrate was isolated as previously described [23]. Single cell suspensions of spleens were obtained as previously described [22]. DCs were isolated using CD11c MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with a purity of ≥90%.

Flow cytometry and BrdU studies

Single cell suspensions were labeled with mAbs according to manufacturer’s protocol, and analyzed by flow-cytometry. mAbs against mouse CD3, CD4, CD8α, CD11c, CD11b, CD19, CD25, CD45, CD45.1, CD49b, CD115, CD117, CD135, Gr-1, B220, MHCII, TER-119, Foxp3, IFN-γ, Ki67, BrdU and corresponding isotype controls were obtained from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA) and eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). AH1423-431/Ld tetramer (AH-1 tetramer) was obtained through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Tetramer Facility and the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Bethesda, MD, USA). Staining was done as previously described [22]. For BrdU studies, animals were intraperitoneally injected with 1 mg of BrdU (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) on day 21 after tumor implantation and fed BrdU-containing water (0.8 mg/ml) for additional 2 days.

Adoptive transfer of monocytes

Bone marrow (BM) monocytes were isolated from BALB/c-CD45.1+ mice using biotin-conjugated CD115 and anti-biotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec), with a purity of 92–96% [24]. 107 of CD115+ monocytes were injected in lateral tail vein of Cy-treated or untreated tumor-bearing mice on day 16 after tumor injection.

Cytokine production assessment

Liver and splenic DCs were cultured overnight in complete medium and production of IL-12p40 and IL-10 was quantified using Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Assessment of T cell responses

Liver and splenic DCs were cultured overnight in complete medium. In designated experiments, 5 μM of CpG1826 oligodeoxynucleotide was added to DCs. For mixed lymphocyte reaction, DCs were retrieved the following day, washed thoroughly and irradiated with 3,000 cGy before plating in triplicates with C57BL/6 lymph node cells. For assessment of Treg proliferative responses, naïve BALB/c CD4+CD25+ T cells were sorted from pooled spleens and lymph nodes using FACSVantage (BD Biosciences) and added to hepatic or splenic DCs at a 1:1 ratio. In both assays, 1 μCi/well 3[H] thymidine was added during the last 16 h of a 96-h incubation.

Quantitative analysis of DC gene expression

Total RNA was purified from isolated DCs using RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). cDNA was subjected to polymerase chain reaction amplification using primers for 18s rRNA, IL-12p40, TNF-α, MCP-1, and MIP-1α [25–29], using SYBR Premix Ex Taq DNA polymerase (Takara Bio, Madison, WI, USA) and MyiQ light cycler (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were calculated using one-way ANOVA, Mann–Whitney U tests, or log-rank test, as appropriate. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Cy augments antitumor immunity and its efficacy cannot be improved by Treg depletion

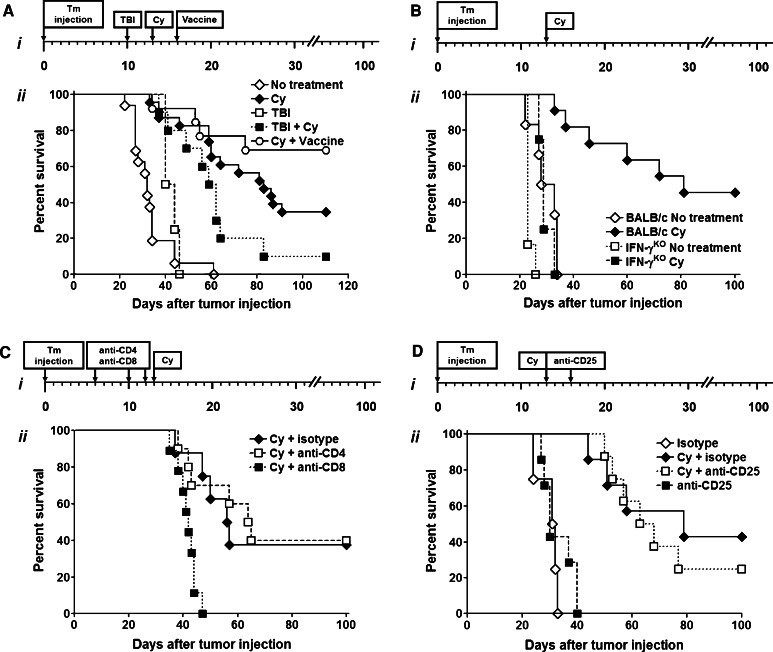

To mimic the pathophysiologic scenario of advanced malignancy, we used a CT26 hepatic metastasis model of colon cancer [23]. In initial experiments, we compared the efficacy of the nonmyeloablative dose of TBI (200 cGy on day 10), Cy (200 mg/kg on day 13), or both modalities combined. We found, that in this model, growth of hepatic metastases was not inhibited by administering TBI alone, while treatment with Cy resulted in long-term tumor-free survival in approximately 40% of animals (Fig. 1a). The administration of TBI prior to Cy not only failed to improve the efficacy of treatment, but decreased the beneficial effect of Cy, suggesting that antitumor efficacy of Cy cannot be explained solely by its cytotoxic activity. To confirm that antitumor immunity can be augmented in this setting we used a strategy of administering tumor vaccine after Cy [30]. Administration of tumor vaccine comprised of irradiated CT26 cells together with GM-CSF-secreting bystander cells resulted in augmented survival and induction of long-term tumor-specific immunity (P < 0.05 for Cy vs. Cy followed by vaccine; Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Nonmyeloablative conditioning with Cy augments endogenous antitumor immunity without the need for hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cy alone increases tumor-free survival. i Experimental schema. ii BALB/c mice were injected with 105 CT26 tumor cells using hemispleen injection technique and then received no additional treatment (open diamond) or were administered 200 cGy of TBI (open square) on day 10 after surgery, 200 mg/kg of Cy intraperitoneally on day 13 (dark filled diamond), combination of TBI and Cy (dark filled square) or Cy followed by vaccine on day 16 (open circle). P < 0.005 for Cy vs. no treatment; P < 0.01 for no treatment vs. TBI, TBI + Cy vs. no treatment, and Cy vs. Cy + vaccine. b Intact IFN-γ-mediated T cell responses are necessary for preservation of Cy-mediated antitumor efficacy. i Experimental schema. ii BALB/c or IFN-γKO mice were injected with CT26 and left untreated (dark filled diamond—BALB/c; dark filled square—IFN-γKO) or Cy was administered (open diamond—BALB/c; open square—IFN-γKO) on day 13. P < 0.0001 for BALB/c no treatment vs. BALB/c Cy, IFN-γKO Cy, and IFN-γKO no treatment. c Depletion of CD4+ T cells does not affect Cy efficacy, while CD8+ T cell elimination completely eliminates Cy’s antitumor-effect. i Experimental schema. ii BALB/c mice were injected with CT26 and then treated intraperitoneally on days 6, 10, and 12 with 0.25 mg of IgG2b (dark filled diamond), anti-CD4 (open square), or anti-CD8 (dark filled square) and then injected with Cy on day 13 after tumor injection. P < 0.005 for Cy + isotype and Cy + anti-CD4 vs. Cy + anti-CD8. d Treg depletion after Cy administration does not improve survival of tumor-bearing animals. i Experimental schema. ii BALB/c mice were injected with CT26, and treated with Cy or left untreated. Animals then received 0.5 mg of anti-CD25 (open square—Cy treated; dark filled square—untreated) or isotype control (dark filled diamond—Cy treated; open diamond—untreated) on days 13 and 16 after tumor injection. P < 0.005 for Cy + isotype and Cy + anti-CD25 vs. isotype only and anti-CD25 only. In all experiments survival was monitored and is plotted as a function of time after tumor injection. Data are representative of at least three (a, b) or two (c, d) independent experiments

In the next set of experiments, we used IFN-γKO mice to determine if the beneficial effect of Cy administration was primarily due to direct cytotoxicity toward tumor cells or an active immune response. Tumor-bearing IFN-γKO and wild-type BALB/c mice were treated with Cy or left untreated. Survival of tumor-bearing IFN-γKO mice receiving Cy was inferior to that of identically treated wild-type BALB/c mice and similar to that of untreated IFN-γKO or BALB/c controls (Fig. 1b). The complete loss of Cy’s therapeutic effect in IFN-γKO mice suggests that potent T cell IFN-γ-mediated responses are required for successful antitumor immunity in our model.

Next, we evaluated contribution of T cell subsets to the Cy-mediated antitumor effect. Tumor-bearing animals were injected intraperitoneally with 0.25 mg of anti-CD4, anti-CD8, or IgG2b isotype on days 6, 10, and 12 after tumor challenge. We found that CD8, but not CD4, depletion completely abrogated the antitumor efficacy of Cy (Fig. 1c). Lack of Cy-mediated antitumor effect after CD8 depletion further strengthens the previous finding that Cy’s effect is a result of immune response, rather than the direct killing of tumor.

The efficacy of Cy in augmenting antitumor immunity has been mostly attributed to its effect on elimination of regulatory CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells. To assess whether the effects of Cy could be augmented by further depletion of Tregs, we used a CD25-depleting antibody (PC61) known to augment antitumor immunity [31]. Tumor-bearing Cy-treated or untreated animals received anti-CD25 mAb, or IgG1 isotype control, intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.5 mg on days 13 and 16 after tumor injection. This dose of anti-CD25 mAb induced depletion of CD25+ Tregs in spleen and liver of the tumor-bearing mice, severity and duration of which surpassed those seen with Cy treatment alone (Supplementary Figure 1). We found that anti-CD25 treatment, whether alone, or in combination with Cy, provided no additional survival benefit (Fig. 1d). Collectively, these data suggest that Cy is an effective strategy for augmenting CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immune response in the setting of established malignancy and that effects of Cy in this setting extend beyond the elimination of Tregs.

Cy selectively augments expansion of IFN-γ-secreting and tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells without a lasting effect on Tregs and NK cells

Absence of additional benefit of treating tumor-bearing mice with anti-CD25 mAb, led us to investigate the effects of Cy on effector arm of T cell response. Untreated and Cy-treated tumor-bearing animals were analyzed on day 23 after tumor inoculation (10 days after Cy administration) and compared to naïve controls. Analysis focused on liver, representing the tumor site, and spleen, a draining secondary lymphoid tissue. Since the composition of hepatic and splenic mononuclear cell infiltrate in animals treated with surgery and intrasplenic injection of PBS did not differ from that in naïve mice (data not shown), all subsequent experiments used naïve BALB/c mice as controls. We found that 10 days after Cy administration, livers of mice injected with Cy contained higher percentages and absolute numbers of CD8+, but not CD4+ T cells (P < 0.05 for Cy vs. both naïve and untreated tumor-bearing animals; Fig. 2a). The number of T cells in spleen did not differ significantly between the groups (data not shown). CD8+ T cells retrieved from the tumor bed of Cy-treated animals also secreted higher amounts of IFN-γ, when compared to those isolated from untreated or naïve animals (P < 0.05, Fig. 2b). When the total numbers of CD8+ T cells were compared, the difference became even more prominent (Fig. 2b).

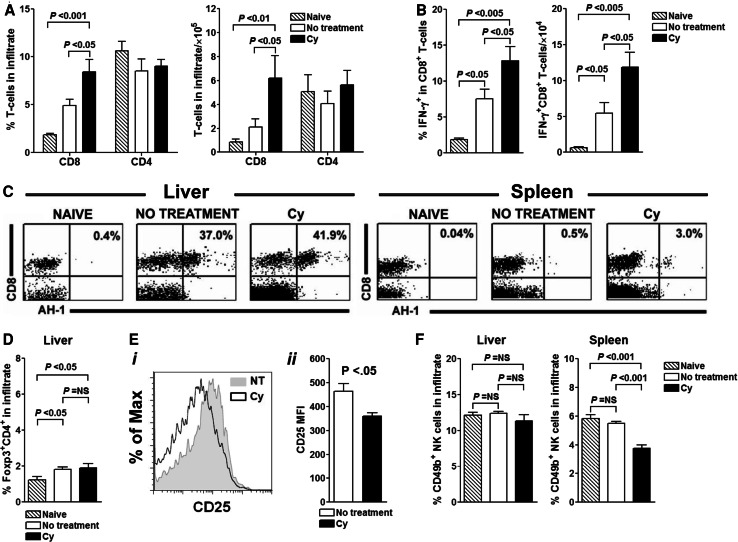

Fig. 2.

Cy suppresses regulatory networks in the target organ and enables homing and persistence of tumor specific AH-1+CD8+ T cells despite heavy tumor burden. Twenty-three days after tumor injection, spleens and livers from three to five mice per treatment group were analyzed for the presence of T cell subsets. a Cy treatment increases CD8+ T cell content of tumor-infiltrated organ while exhibiting minimal effect on CD4+ T cell subset. b Greater proportion of CD8+ T cells from Cy-treated animals secrete IFN-γ. c Presence of tumor specific AH-1+CD8+ T cells is increased after treatment with Cy. d Cy-mediated depletion of Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs is of short duration and by day 10 after Cy injection, Cy treated and untreated animals cannot be distinguished based on composition of infiltrate at tumor site. e Reduced expression of CD25 by Foxp3+CD4+ T cells retrieved from livers of untreated and Cy-treated tumor-bearing mice. i Representative histogram. ii Bar graphs show mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of CD25 on gated Foxp3+CD4+ T cells in liver on day 23 after tumor inoculation and day 10 after Cy treatment. Five mice per treatments group were analyzed. f Cy decreases the percentage of NK cells in the pool of liver-infiltrating leukocytes. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. Data are representative of three separate experiments

Next, we examined the influence of Cy on the antigen-specific T cell response. CT26 cells express AH-1, a MHC class I (H-2d)-restricted tumor-associated antigen not expressed by normal adult tissue [32]. Despite Cy administration, tumor-specific AH-1+CD8+ T cells that were induced by tumor presence persisted in the livers of tumor-bearing hosts (Fig. 2c). These observations suggest that the host immune system recognizes the growing tumor; however, the responding cells are restrained in their ability to promote its eradication [33].

Despite the transient depletion of regulatory Foxp3+CD4+ T cells that occurs early after drug treatment (data not shown), no difference in the pool of Tregs between Cy-treated and untreated animals was present on day 10 after Cy administration (Fig. 2d). These results, together with ineffectiveness of PC61 mAb to further augment antitumor immunity by enhancing Treg depletion, prompted us to examine whether Cy-mediated effects may be in part explained by its influence on Treg functional state. In vitro studies conducted by Lutsiak et al. showed that Tregs from Cy-treated mice exhibit transiently impaired suppressive function that returns to baseline within 10 days after drug administration [17]. To examine the Treg function in vivo we relied on recent data suggesting that functionality of Tregs is reflected in their phenotype. Tang et al. reported that Foxp3+CD4+ T cells present at the inflammatory sites have reduced expression of CD25, a receptor for IL-2, and a critical growth factor for Tregs [34]. We found that cell surface density of CD25 (as assessed through mean fluorescence intensity) on the liver-infiltrating Foxp3+CD4+ T cells of Cy-treated mice was significantly reduced when compared with that found on Tregs in untreated tumor-bearing animals (P < 0.05; Fig. 2e). The reduced CD25 expression on Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs was also evident in spleens of Cy-treated and untreated tumor-bearing mice (data not shown) suggesting that the loss of CD25 expression is result of the drug treatment.

Finally, we examined the effect of Cy on NK cells and found that drug treatment decreases the percentage of NK cells in the pool of liver-infiltrating leukocytes when compared to that in both naïve and untreated tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 2f). This finding suggests that NK cells do not play a significant role in augmented antitumor immunity after Cy administration.

Cy influences the number, phenotypic composition, and turnover of DCs in the liver of tumor-bearing mice

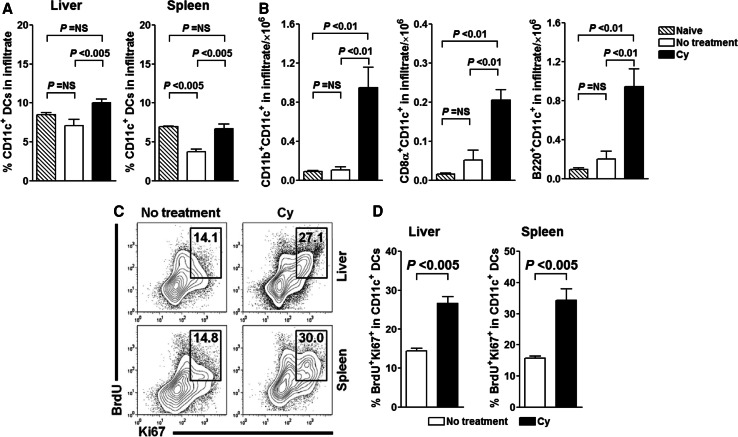

We hypothesized that Cy, through its myelosuppressive effects, perturbs homeostasis and induces turnover of DCs, including those infiltrating the tumor. Cells with a DC morphology and/or expression of DC markers have been repeatedly described to infiltrate murine and human tumors, but the effect of chemotherapy on them remains uncertain [35]. We first determined the effect of Cy on the CD11c+ DCs in liver, representing tumor-infiltrating DCs (TIDCs), and found that on day 23 after tumor inoculation, both percentage of CD11c+ DCs and their absolute count were higher in Cy-treated tumor-bearing animals (P < 0.005; Fig. 3a). In general, hepatic DCs can be categorized into phenotypically and functionally distinct subpopulations, including CD8α−CD11b+CD11c+, CD8α+CD11c+, B220+CD11cint, and CD11c+ DCs expressing none of these molecules [36–38]. We found that Cy administration to tumor-bearing animals induced profound changes in all three defined liver DC subsets (P < 0.01; Fig. 3b). The same pattern and magnitude of change were observed in spleen (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Cy treatment perturbs the DC homeostasis and increases presence of in vivo proliferating hepatic and splenic conventional DCs. Cy-treated or untreated tumor-bearing animals were sacrificed on day 23 after tumor inoculation, livers and spleens were harvested and DC subset composition in mononuclear infiltrate/splenocytes was analyzed. Cy-mediated increase in percentage, as well as in total liver CD11c+ DCs (a), is reflected in the composition of CD11c+ population (b). P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. Data are representative of three independent experiments. c, d CD11c+ DCs in Cy-treated animals have increased proliferation rate in spleen and liver. On day 21 after tumor implantation tumor-bearing Cy-treated or untreated animals were injected with BrdU and kept on BrdU-containing water until analysis. Representative contour plots show Ki67 and BrdU profile of hepatic and splenic CD11c+MHCII+ DCs. Graphs show percentage of Ki67+BrdU+ among total hepatic and splenic CD11c+ DCs. P values were calculated using one-way ANOVA. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments

The described changes in the TIDC pool could be a result of direct Cy-mediated functional alterations of pre-existing TIDCs or Cy-mediated killing of TIDCs with subsequent de novo recruitment of DCs to the tumor site. To address this we assessed proliferation of DCs by analyzing the incorporation of BrdU and expression of Ki-67. We found that DCs retrieved from Cy-treated mice co-expressed BrdU and Ki67 at significantly higher levels than those from tumor-bearing untreated animals (P < 0.005; Fig. 3c, d). The increase in BrdU incorporation in Cy-treated animals was observed for all subtypes of conventional splenic and hepatic DCs (Supplementary Figure 2). Conventional spleen DCs (cDCs) are considered to emerge from the BM precursors as immature cells that must further differentiate and divide in lymphoid organs [39]. Under steady-state conditions, the rate of cDC division is regulated by Flt3 (CD135) receptor signaling, as recently shown using BrdU incorporation and CFSE dilution methods [40]. Whether the observed proliferation of cDCs is result of Cy-induced CD135 receptor signaling or some other mechanisms would need to be determined in future studies. Nonetheless, these results support our hypothesis that through myelosuppression-mediated mechanisms Cy directly influences DC homeostasis and induces their turnover in tumor-bearing host.

Cy induces DC turnover by preferentially recruiting early DC progenitors

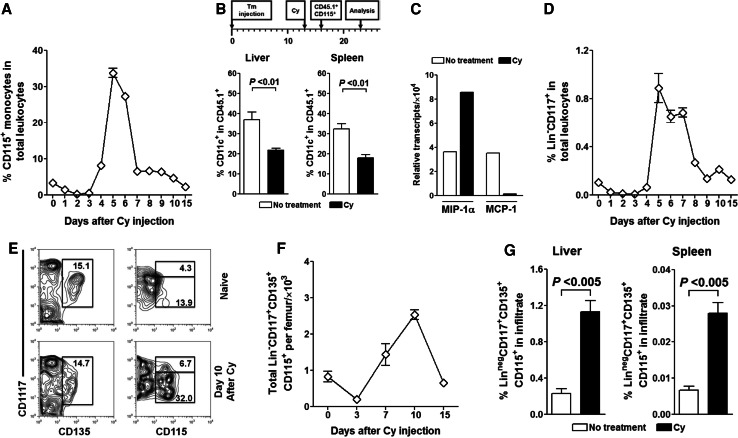

It has been suggested that CD135+ DC progenitors and Gr-1hi monocytes are endowed with immediate DC precursor potential [41]. Since Cy is known to induce myelomonocytosis [42], we examined first whether the observed increase in tissue DCs is a result of monocyte differentiation. In assessing Cy’s effect we found that in naïve (Fig. 4a) and tumor-bearing animals (data not shown), Cy rapidly eliminated circulating monocytes. However, starting on day 4, monocytes began their recovery surge and on day 5 achieved peak levels that were tenfold higher than in steady-state, followed by rapid return to pre-treatment levels by day 10. To track their DC-differentiation potential, we adoptively transferred BM-derived monocytes that differed from the host in the expression of CD45 allele. In sorting monocytes for adoptive transfer we relied on their expression of CD115+, a receptor for colony-stimulating factor 1. Isolated CD115+ monocytes from BALB/c-CD45.1+ mice were transferred to Cy-treated or -untreated tumor-bearing wild-type BALB/c (CD45.2+) mice on day 16 (day 3 after Cy treatment and point of maximal monocyte nadir). Surprisingly, we found that on day 23 a significantly higher percentage of monocyte-derived DCs was present in liver and spleen of untreated vs. Cy-treated mice (P < 0.01; Fig. 4b). CD45.1+-derived DCs in both organs expressed intermediate levels of CD11c (data not shown), which is consistent with their monocytic origin [43]. Additional analysis revealed that, regardless of Cy administration, monocyte-derived DCs had unrestricted maturation potential as evidenced by expression of high levels of MHC class II (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Cy perturbs DC homeostasis by mobilizing DC precursors in naïve and tumor-bearing mice. a Cy treatment induces rebound monocytosis. Naïve BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally injected with 200 mg/kg of Cy and changes in circulating monocytes were sequentially monitored. b Monocytes are not the primary source of post-Cy occurring CD11c+ DCs in spleen and liver of tumor-bearing mice. Seven days after adoptive transfer of congenic CD45.1+CD115+ monocytes to Cy-treated or untreated tumor-bearing BALB/c (CD45.2+) mice, livers and spleens were analyzed for the presence of CD45.1+CD11c+ DCs. Bar graphs show % conversion of monocytes into CD11c+ DCs. c Gene expression profile of hepatic DCs is suggestive of their CDP, rather than monocytic, origin. On day 23 after tumor inoculation, total RNA was extracted from isolated hepatic CD11c+ DCs and analyzed for expression of MIP-1α and MCP-1 using quantitative RT-PCR. d Cy mobilizes primitive HSCs to peripheral circulation. After Cy administration, naïve BALB/c mice were serially bled and analyzed for presence of Lin−CD117+ HSCs. e, f Cy treatment mobilizes early DC progenitors in BM. e Representative contour plots and histograms show the profile of naïve and Cy-treated (day 10) Lin− BM cells as assessed through early DC progenitor-defining markers. f Changes in the total numbers of early DC progenitors in BM of Cy-treated animals. g Cy-mobilized early DC progenitors are recruited to livers and spleens of tumor-bearing animals. CT26 injected animals were treated with Cy or left untreated and analyzed for presence of Lin−CD117+CD135+ cells in livers and spleens 23 days after tumor injection. Bar graphs show threefold increase in percentage of early DC progenitors in livers and spleens of Cy-treated animals

Dendritic cell homeostasis in steady-state is dependent on the rate of DC progenitor input from blood, cell division, and cell death. Recruitment of DCs to both normal and malignant tissues is the result of their response to various chemokines. We focused on MCP-1 and MIP-1α, two chemokines known to be critical for recruitment of DCs. Both chemokines are secreted by liver DCs [44], but the expression of MCP-1 is associated with monocyte recruitment [45] while MIP-1α plays a role in recruitment and proliferation of DC precursor populations in vivo [46, 47]. We found that hepatic CD11c+ DCs isolated from untreated tumor-bearing mice expressed mRNA for MCP-1 at higher levels than those from Cy-treated animals. In contrast, CD11c+ DCs from Cy-treated tumor-bearing animals predominantly transcribed MIP-1α (Fig. 4c).

Since we could not attribute increase in DCs to Cy-induced monocyte mobilization, we focused next on CD135+ DC progenitors. We observed that, similarly to changes in circulating monocytes, Cy-induced prominent mobilization of lineage (Lin; CD3+CD4+CD8+CD11b+Gr-1+B220+CD49b+TER-119+) negative CD117+ population that includes primitive HSCs and/or multipotent progenitors (Fig. 4d). This increase in circulating HSCs was result of increased numbers of these cells in the BM of Cy-treated animals (data not shown). This prompted us to examine the recently identified common DC precursors (CDPs) [48], a population contained within the Lin−CD117+ HSCs [40]. This population can be simply identified in the BM as a Lin− population characterized by expression of CD115, CD135, and intermediate levels of CD117 (Lin−CD115+CD135+CD117int) [40, 48]. We observed prominent increase in the percentage and total numbers of Lin−CD115+CD117intCD135+ CDPs in the BM leukocytes of Cy-treated mice (Fig. 4e, f). Moreover, we found an increase in the CDPs in both spleen and liver of Cy-treated tumor-bearing animals on day 23 after tumor injection (Fig. 4g). While this work was in progress it became clear that beside CDPs, Lin−CD115+CD117intCD135+ fraction also contains macrophage and DC progenitors (MDPs) which are characterized by the expression of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1 [49, 50]. As we had no means to distinguish CX3CR1+ from CXCR1− Lin−CD115+CD117intCD135+ cells (i.e., MDPs from CDPs) we will refer to this phenotype (Lin−CD115+CD117intCD135+) hereafter as “early DC progenitors”.

Overall, these results suggest that tumor milieu promotes increased accumulation of monocytes, rather than DCs, and that in Cy-treated tumor-bearing host recruited DCs originate from mobilized early DC progenitors. This, to our knowledge, is the first demonstration of drug treatment-induced recruitment of early DC progenitors; however, it is not entirely surprising considering the stem cell mobilization properties of Cy.

Cytokine-secretion patterns and functional characteristics of tumor-infiltrating DCs are influenced by Cy

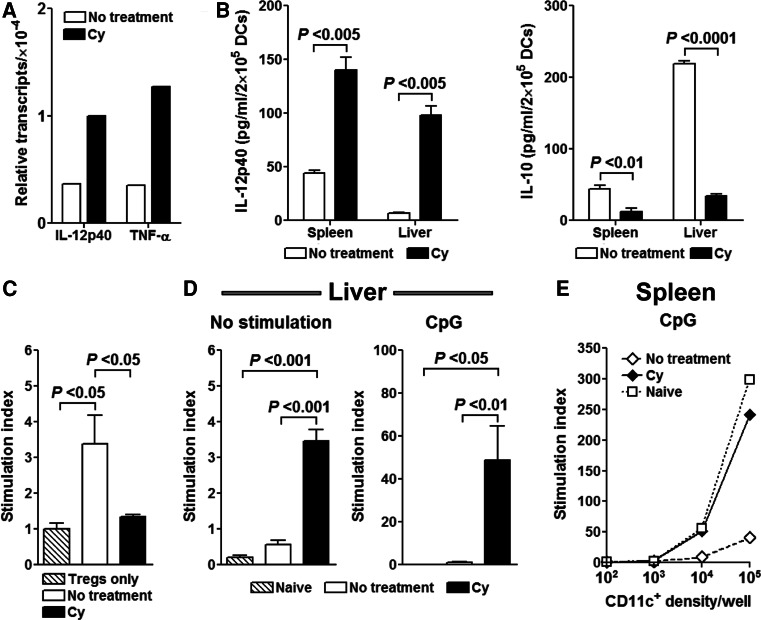

Next, we analyzed the functional ability TIDCs to prime T cell responses. We found that DCs retrieved from the Cy-treated tumor-bearing animals expressed mRNA for proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-12p40 at higher levels than tumor-bearing untreated mice (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, DCs isolated from livers of Cy-treated tumor-bearing mice secreted 16-fold higher amounts of IL-12p40, as assayed by ELISA (P < 0.005, Fig. 5b). In contrast, DCs isolated from untreated animals produced sixfold higher amounts of IL-10 (P < 0.0001, Fig. 5b) a known immunosuppressive cytokine. Similar patterns were observed in the spleen, suggesting that Cy treatment has a direct proinflammatory effect on both tumor-infiltrating (liver) and systemic (spleen) DCs.

Fig. 5.

Cy influences the cytokine profile of DCs at the tumor site and reverses tumor-induced DC paralysis. a Liver CD11c+ cells were isolated on day 23 and total RNA was extracted. cDNA was generated by reverse transcription and analyzed for presence of TNF-α and IL-12p40 using quantitative RT-PCR. b On day 23 post-tumor implantation, isolated hepatic and splenic CD11c+ cells were incubated for 48 h in complete medium and production of IL-12p40 and IL-10 was assessed by ELISA. c Following Cy treatment, newly occurring liver CD11c+ cells are inefficient in stimulating naïve CD4+CD25+ T cells. Liver CD11c+ DCs were isolated on day 23 and cultured with naïve BALB/c CD4+CD25+ T cells at a 1:1 ratio for 72 h after which 3[H] Thymidine was added. Data are presented as stimulation index (determined by comparing proliferation of CD4+CD25+ T cells cocultured with isolated DCs with that of CD4+CD25+ T cells cultured in medium alone according to the formula: measured cpm/cpm medium). d Functional DC paralysis in the liver and spleen is reversed with Cy treatment. On day 23 after tumor injection CD11c+ cells were isolated from spleens and livers of naïve, Cy-treated and untreated tumor-bearing mice and cultured overnight in complete medium with addition of nothing or 5 μg/ml of CpG1826. The next day, DCs were irradiated and cocultured with 105 C57BL/6 LN cells (ratio of T cells to DCs in liver 1:1, in spleen 1:1 to 1,000:1). 3[H] Thymidine was added after 72 h of stimulation. Data are presented as stimulation index

Ghiringhelli et al. have shown that TIDC may perpetuate tumor tolerance through their interaction with CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs [51]. Next, we examined whether CD11c+ DCs recovered from tumor-bearing untreated or Cy-treated mice have differential effect on stimulating CD4+CD25+ T cell proliferation. On day 23 after tumor inoculation, splenic and liver CD11c+ DCs were retrieved from Cy-treated and untreated tumor-bearing animals and cultured with freshly isolated BALB/c CD4+CD25+ T cells. Indeed, DCs isolated from livers of Cy-treated mice were ineffective in inducing proliferation of CD4+CD25+ T cells in contrast to those isolated from tumor-bearing untreated animals (P < 0.05, Fig. 5c). However, these results were not observed with splenic DCs (data not shown), suggesting that DCs in Cy-treated mice are less influenced by intratumor Tregs and may be more effective in inducing in situ antitumor immune responses.

Previous observations also suggested that TIDCs are functionally paralyzed due to the presence of inhibitory signals such as IL-10 and TGF-β in the tumor milieu [51, 52]. To determine the effect of Cy on functional characteristics of DCs, we assessed their ability to prime de novo immune responses in a mixed leukocyte reaction-type assay. Hepatic and splenic CD11c+ DCs isolated from Cy-treated and untreated tumor-bearing animals were cocultured with C57BL/6 T cells and proliferation of allogeneic T cells was assessed 72 h later. We found that DCs isolated from livers of Cy-treated tumor-bearing mice induced a prominent proliferation of allogeneic T cells in contrast to DCs isolated from the livers of untreated tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 5d). In addition, CpG stimulation of both hepatic and splenic DCs isolated from tumor-bearing mice had no effect on their ability to stimulate allogeneic T cells, whereas a prominent effect was induced by CpGs on DCs from Cy-treated mice (Fig. 5d, e). A similar lack of DC activation was observed if DCs from tumor-bearing animals were stimulated with anti-CD40 or a combination of CpG1826 and anti-CD40 (data not shown).

In conclusion, these data are consistent with studies showing that TIDCs are refractory to ex vivo maturation stimuli and may be in a state of functional paralysis in vivo [52], but also imply that Cy-induced DCs carry a more proinflammatory profile, are released from influence of immunoregulatory networks, and capable of initiating de novo immune responses.

Discussion

The results of this study highlight a novel finding that Cy, a well characterized and widely used chemotherapeutic agent, can influence antitumor immunity, not only through direct effects on T cells, but also by affecting the DC homeostasis in the tumor-bearing host. We found that Cy-mediated antitumor immunity in the setting of pre-established malignancy is predominantly mediated by CD8+ T cells and that despite transient removal of Tregs Cy’s effect cannot be further augmented with CD25+ Treg depletion. Additionally, we observed that Cy administration, through myelosuppression and rebound reconstitution of myelopoiesis, leads to reversal of systemic and in situ tumor-induced DC paralysis. Moreover, Cy-mobilized proliferating early DC progenitors to the tumor site where they yielded new DCs. Therefore, similar to the lymphodepleting paradigm, the post myelosuppressive environment may be advantageous for development of antitumor immunity.

In contrast to studies showing Cy-mediated antitumor immunity to be a primary function of Treg elimination, we found that although Tregs are depleted after Cy treatment, they rapidly reconstitute both secondary lymphoid tissues and tumor site. The rapid repopulation of Treg compartment after Cy-induced perturbation is likely a result of a TGF-β-abundant environment in tumor-bearing hosts that provides a stealthy impetus for a rapid Treg proliferation [51]. Still, prolonged CD25 depletion in the post-Cy setting provided no added benefit to the Cy treatment alone. This finding, although somewhat surprising, is consistent with published studies in which this strategy has not enhanced other immunomodulatory approaches in the setting of established malignancy [53–55]. Clinical studies using the Treg-directed strategies such as a CD25-directed immunotoxin (LMB-2) or recombinant IL-2 fused to diphtheria toxin (ONTAK) failed to report any significant clinical responses despite showing decrease in the number of Tregs in peripheral blood and heightened antitumor T cell responses in vitro [56, 57]. On the other hand, as recently demonstrated, adoptive transfer of purified CD25+ Tregs into Cy-treated mice directly negates the curative property of the drug [55]. However, ineffectiveness of CD25-depletion in the same model of pre-established mesothelioma strongly implied the importance of other mechanisms by which Cy augments T cell-mediated antitumor immunity.

Several findings of this study are relevant for understanding multifaceted mechanisms behind Cy’s beneficial effects on augmenting antitumor immunity. First, Cy, through its myelosuppressive action, eliminates TIDCs, mobilizes early DC precursors that through their rapid proliferation in periphery increase the presence of new APCs that can prime de novo T cell responses. This is supported by high expression of Ki-67 in cDCs and increase in Lin−CD115+CD117intCD135+ population in spleen and liver of tumor-bearing mice.

Current strategies to modulate in vivo DCs in the tumor-bearing host are mostly focused on their activation and/or reversal of their functional paralysis rather than modulating their in vivo homeostasis [52, 58]. In this regard, effects of Cy are unique since through myelosuppressive effects on TIDCs and mobilization of early DC progenitors it directly influences the DC homeostasis in tumor-bearing host. What the contribution of MDPs and CDPs is to DC pool and augmenting of T cell-mediated antitumor immunity remains to be determined. These studies would require the use of CX3CR1-gfp+ mice which would provide additional advantage of the ease of sorting these early DC precursors for functional in vivo studies. Second, Cy, besides transient quantitative depletion of Tregs may also have an effect on their in vivo function. Lutsiak et al. have shown that Cy administration leads to the loss of their suppressor functionality as assessed in vitro [17]. We found that Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs retrieved from Cy-treated tumor-bearing mice express lower amounts of CD25, a receptor for IL-2, a critical Treg growth factor. Reduced expression of CD25 on Foxp3+CD4+ Tregs has been associated with local loss of Treg:effector T cell balance and correlates with a heightened immune response [34]. Further characterization of Tregs persisting in tumor-bearing host after Cy administration and why their additional elimination with PC61 mAb does not augment antitumor immunity is required. Finally, Cy through the induction of immunogenic cell death leads to increased phagocytosis of apoptotic tumor cells by DCs leading subsequently to their activation (Supplementary Figure 3). These effects of Cy, coupled with drug’s sparing effects on pre-existing tumor-specific CD8+ T cells may be essential for observed unleashing of antitumor immunity after drug administration. Thus, Cy has a direct impact on DC–T cell interactions in tumor-bearing host that ultimately lead to a better priming of tumor-specific T cells. These observations augment the notion that mobilization of early DC precursors to the site of ongoing immune response and their differentiation into DCs can lead to optimal T cell priming [39, 46]. Cy, thus, through its unique ability to mobilize DC precursors can influence the DC homeostasis both in situ and systemically.

In conclusion, previous studies have suggested that beneficial effects of Cy in augmenting antitumor immunity are primarily a result of drug’s ability to eliminate Tregs and/or augment the homeostasis-driven expansion of pre-existing tumor-specific effector T cells [7–9]. Our study provides a novel observation that Cy influences antitumor immune responses by resetting the DC homeostasis in tumor-bearing host.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

References

- 1.Lake RA, Robinson BW. Immunotherapy and chemotherapy—a practical partnership. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:397–405. doi: 10.1038/nrc1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zitvogel L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Andre F, Tesniere A, et al. The anticancer immune response: indispensable for therapeutic success? J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1991–2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI35180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowak AK, Lake RA, Robinson BWS. Combined chemoimmunotherapy of solid tumours: improving vaccines? Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:975. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Fimia GM, Apetoh L, et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med. 2007;13:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, Antony PA, Palmer DC, et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dummer W, Niethammer AG, Baccala R, Lawson BR, Wagner N, et al. T cell homeostatic proliferation elicits effective antitumor autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:185–192. doi: 10.1172/JCI15175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ercolini AM, Ladle BH, Manning EA, Pfannenstiel LW, Armstrong TD, et al. Recruitment of latent pools of high-avidity CD8(+) T cells to the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1591–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North RJ. Cyclophosphamide-facilitated adoptive immunotherapy of an established tumor depends on elimination of tumor-induced suppressor T cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1063–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.4.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghiringhelli F, Larmonier N, Schmitt E, Parcellier A, Cathelin D, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curative. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:336–344. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Bowerman NA, Salama JK, Schmidt H, Spiotto MT, et al. Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:49–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulos CM, Wrzesinski C, Kaiser A, Hinrichs CS, Chieppa M, et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2197–2204. doi: 10.1172/JCI32205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wrzesinski C, Paulos CM, Gattinoni L, Palmer DC, Kaiser A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells promote the expansion and function of adoptively transferred antitumor CD8 T cells. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:492–501. doi: 10.1172/JCI30414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, Hughes MS, Royal R, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RJ, Barber JP, Vala MS, Collector MI, Kaufmann SH, et al. Assessment of aldehyde dehydrogenase in viable cells. Blood. 1995;85:2742–2746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moyo VM, Smith D, Brodsky I, Crilley P, Jones RJ, et al. High-dose cyclophosphamide for refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2002;100:704–706. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salem ML, Kadima AN, El-Naggar SA, Rubinstein MP, Chen Y, et al. Defining the ability of cyclophosphamide preconditioning to enhance the antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell response to peptide vaccination: creation of a beneficial host microenvironment involving type I IFNs and myeloid cells. J Immunother. 2007;30:40–53. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211311.28739.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutsiak ME, Semnani RT, De Pascalis R, Kashmiri SV, Schlom J, et al. Inhibition of CD4(+)25(+) T regulatory cell function implicated in enhanced immune response by low-dose cyclophosphamide. Blood. 2005;105:2862–2868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibe S, Qin Z, Schuler T, Preiss S, Blankenstein T. Tumor rejection by disturbing tumor stroma cell interactions. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1549–1560. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Di Pucchio T, Santini SM, Bracci L, et al. Cyclophosphamide induces type I interferon and augments the number of CD44(hi) T lymphocytes in mice: implications for strategies of chemoimmunotherapy of cancer. Blood. 2000;95:2024–2030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angulo I, de las Heras FG, Garcia-Bustos JF, Gargallo D, Munoz-Fernandez MA, et al. Nitric oxide-producing CD11b(+)Ly-6G(Gr-1)(+)CD31(ER-MP12)(+) cells in the spleen of cyclophosphamide-treated mice: implications for T-cell responses in immunosuppressed mice. Blood. 2000;95:212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pelaez B, Campillo JA, Lopez-Asenjo JA, Subiza JL. Cyclophosphamide induces the development of early myeloid cells suppressing tumor cell growth by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2001;166:6608–6615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luznik L, Slansky JE, Jalla S, Borrello I, Levitsky HI, et al. Successful therapy of metastatic cancer using tumor vaccines in mixed allogeneic bone marrow chimeras. Blood. 2003;101:1645–1652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain A, Slansky JE, Matey LC, Allen HE, Pardoll DM, et al. Synergistic effect of a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-transduced tumor vaccine and systemic interleukin-2 in the treatment of murine colorectal cancer hepatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:810–820. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tacke F, Ginhoux F, Jakubzick C, van Rooijen N, Merad M, et al. Immature monocytes acquire antigens from other cells in the bone marrow and present them to T cells after maturing in the periphery. J Exp Med. 2006;203:583–597. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marino JH, Cook P, Miller KS. Accurate and statistically verified quantification of relative mRNA abundances using SYBR Green I and real-time RT-PCR. J Immunol Methods. 2003;283:291–306. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(03)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizzitelli A, Berthier R, Collin V, Candeias SM, Marche PN. T lymphocytes potentiate murine dendritic cells to produce IL-12. J Immunol. 2002;169:4237–4245. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitazawa M, Oddo S, Yamasaki TR, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation exacerbates tau pathology by a cyclin-dependent kinase 5-mediated pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8843–8853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2868-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Overbergh L, Giulietti A, Valckx D, Decallonne R, Bouillon R, et al. The use of real-time reverse transcriptase PCR for the quantification of cytokine gene expression. J Biomol Tech. 2003;14:33–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitrasinovic OM, Perez GV, Zhao F, Lee YL, Poon C, et al. Overexpression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor on microglial cells induces an inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30142–30149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104265200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machiels JP, Reilly RT, Emens LA, Ercolini AM, Lei RY, et al. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel enhance the antitumor immune response of granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor-secreting whole-cell vaccines in HER-2/neu tolerized mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3689–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi S, Fujita T, et al. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang AY, Gulden PH, Woods AS, Thomas MC, Tong CD, et al. The immunodominant major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen of a murine colon tumor derives from an endogenous retroviral gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9730–9735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen LT, Elford AR, Murakami K, Garza KM, Schoenberger SP, et al. Tumor growth enhances cross-presentation leading to limited T cell activation without tolerance. J Exp Med. 2002;195:423–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Q, Adams JY, Penaranda C, Melli K, Piaggio E, et al. Central role of defective interleukin-2 production in the triggering of islet autoimmune destruction. Immunity. 2008;28:687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:941–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Connell PJ, Morelli AE, Logar AJ, Thomson AW. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mouse hepatic CD8{alpha}+ lymphoid-related dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:795–803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:151–161. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pillarisetty VG, Shah AB, Miller G, Bleier JI, DeMatteo RP. Liver dendritic cells are less immunogenic than spleen dendritic cells because of differences in subtype composition. J Immunol. 2004;172:1009–1017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.del Hoyo GM, Martin P, Vargas HH, Ruiz S, Arias CF, et al. Characterization of a common precursor population for dendritic cells. Nature. 2002;415:1043. doi: 10.1038/4151043a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waskow C, Liu K, Darrasse-Jeze G, Guermonprez P, Ginhoux F, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 is required for dendritic cell development in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:676–683. doi: 10.1038/ni.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naik SH. Demystifying the development of dendritic cell subtypes, a little. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:439–452. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sefc L, Psenak O, Sykora V, Sulc K, Necas E. Response of hematopoiesis to cyclophosphamide follows highly specific patterns in bone marrow and spleen. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2003;12:47–61. doi: 10.1089/152581603321210136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, Greenshtein L, Gildor B, et al. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:171–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drakes ML, Zahorchak AF, Takayama T, Lu L, Thomson AW. Chemokine and chemokine receptor expression by liver-derived dendritic cells: MIP-1alpha production is induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide and interaction with allogeneic T cells. Transpl Immunol. 2000;8:17–29. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(00)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu B, Rutledge BJ, Gu L, Fiorillo J, Lukacs NW, et al. Abnormalities in monocyte recruitment and cytokine expression in monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoneyama H, Matsuno K, Zhang Y, Murai M, Itakura M, et al. Regulation by chemokines of circulating dendritic cell precursors, and the formation of portal tract-associated lymphoid tissue, in a granulomatous liver disease. J Exp Med. 2001;193:35–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Yoneyama H, Wang Y, Ishikawa S, Hashimoto S-I, et al. Mobilization of dendritic cell precursors into the circulation by administration of MIP-1{alpha} in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:201–209. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Onai N, Obata-Onai A, Schmid MA, Ohteki T, Jarrossay D, et al. Identification of clonogenic common Flt3+M-CSFR+ plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1207–1216. doi: 10.1038/ni1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, et al. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. 2009;324:392–397. doi: 10.1126/science.1171243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Auffray C, Fogg DK, Narni-Mancinelli E, Senechal B, Trouillet C, et al. CX3CR1+ CD115+ CD135+ common macrophage/DC precursors and the role of CX3CR1 in their response to inflammation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:595–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, Parcellier A, Schmitt E, et al. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-{beta}-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:919–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vicari AP, Chiodoni C, Vaure C, Ait-Yahia S, Dercamp C, et al. Reversal of tumor-induced dendritic cell paralysis by CpG immunostimulatory oligonucleotide and anti-interleukin 10 receptor antibody. J Exp Med. 2002;196:541–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elpek KG, Lacelle C, Singh NP, Yolcu ES, Shirwan H. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells dominate multiple immune evasion mechanisms in early but not late phases of tumor development in a B cell lymphoma model. J Immunol. 2007;178:6840–6848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Simpson TR, Shen Y, Littman DR, et al. Limited tumor infiltration by activated T effector cells restricts the therapeutic activity of regulatory T cell depletion against established melanoma. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2125–2138. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van der Most RG, Currie AJ, Mahendran S, Prosser A, Darabi A, et al. Tumor eradication after cyclophosphamide depends on concurrent depletion of regulatory T cells: a role for cycling TNFR2-expressing effector-suppressor T cells in limiting effective chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(8):1219–1228. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0628-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, Yang BK, Coleman D, et al. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powell DJ, Jr, Felipe-Silva A, Merino MJ, Ahmadzadeh M, Allen T, et al. Administration of a CD25-directed immunotoxin, LMB-2, to patients with metastatic melanoma induces a selective partial reduction in regulatory T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:4919–4928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mende I, Engleman EG. Breaking self-tolerance to tumor-associated antigens by in vivo manipulation of dendritic cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;380:457–468. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-395-0_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.