Abstract

Purpose

Prostate cancer (PC) is a major health problem. Overexpression of the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) in PC, but not in the hyperplastic prostate, provides a promising target for staging and monitoring of PC. Based on the assumption that cancer cells have increased metabolic activity, metabolism-based tracers are also being used for PC imaging. We compared GRPR-based targeting using the 68Ga-labelled bombesin analogue AMBA with metabolism-based targeting using 18F-methylcholine (18F-FCH) in nude mice bearing human prostate VCaP xenografts.

Methods

PET and biodistribution studies were performed with both 68Ga-AMBA and 18F-FCH in all VCaP tumour-bearing mice, with PC-3 tumour-bearing mice as reference. Scanning started immediately after injection. Dynamic PET scans were reconstructed and analysed quantitatively. Biodistribution of tracers and tissue uptake was expressed as percent of injected dose per gram tissue (%ID/g).

Results

All tumours were clearly visualized using 68Ga-AMBA. 18F-FCH showed significantly less contrast due to poor tumour-to-background ratios. Quantitative PET analyses showed fast tumour uptake and high retention for both tracers. VCaP tumour uptake values determined from PET at steady-state were 6.7 ± 1.4%ID/g (20–30 min after injection, N = 8) for 68Ga-AMBA and 1.6 ± 0.5%ID/g (10–20 min after injection, N = 8) for 18F-FCH, which were significantly different (p <0.001). The results in PC-3 tumour-bearing mice were comparable. Biodistribution data were in accordance with the PET results showing VCaP tumour uptake values of 9.5 ± 4.8%ID/g (N = 8) for 68Ga-AMBA and 2.1 ± 0.4%ID/g (N = 8) for 18F-FCH. Apart from the GRPR-expressing organs, uptake in all organs was lower for 68Ga-AMBA than for 18F-FCH.

Conclusion

Tumour uptake of 68Ga-AMBA was higher while overall background activity was lower than observed for 18F-FCH in the same PC-bearing mice. These results suggest that peptide receptor-based targeting using the bombesin analogue AMBA is superior to metabolism-based targeting using choline for scintigraphy of PC.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography, Bombesin, Prostatic neoplasms, Xenograft model, Choline, Metabolism-based tracer

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths and the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men in Western countries [1]. Measurement of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is widely used for the detection of early PC [2, 3] and PSA-based screening has resulted in a sharp increase in PC detection. As long as PC is organ-confined, prostate surgery or radiation therapy with curative intent is the first choice of treatment. However, when facing metastasized PC, curative treatment is no longer available and palliative hormone ablation therapy is indicated. Therefore, accurate staging of early PC at the time of diagnosis as well as monitoring of patients following local or systemic treatment are crucial steps in the management of the disease.

The accuracy of conventional imaging techniques—such as transrectal ultrasonography, CT, MRI and bone scintigraphy—is not adequate to determine the extent of PC at diagnosis and to visualize micrometastases [4–6]. New and more sensitive, preferably non-invasive, imaging strategies are required. Molecular imaging by nuclear scintigraphy using PET or SPECT may provide alternative technologies for detection. It enables biochemical cellular targets, such as cell-specific receptors, and more general metabolic processes to be targeted with tracers coupled to radionuclides for sensitive imaging.

In peptide receptor-based scintigraphy, radiolabelled peptides are used to target specific cell membrane receptors. For PC imaging the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) is a promising target since this receptor is overexpressed in malignant cells originating from the prostate while normal and hyperplastic prostate cells show low or no expression of GRPR [7]. Gastrin-releasing peptide, which consists of 27 amino acids, is the mammalian homologue of the linear tetradecapeptide bombesin (BN) found in amphibians. Both peptides are natural ligands with a very high affinity for the GRPR. Several (predominantly BN based) analogues which can be labelled with radionuclides have been developed and tested for their potential to treat and image PC using SPECT and PET modalities; for review see Schroeder et al. [8]. AMBA is a BN analogue which has shown good targeting performance in (pre)clinical studies [8–10]. It is coupled to the DOTA chelator which enables labelling with 68Ga, a positron-emitting radionuclide suitable for PET, resulting in 68Ga-DOTA-AMBA (68Ga-AMBA).

Apart from peptide receptor-based targeting, metabolism-based tracers are also being used to image cancer cells. Metabolic targeting is based on the assumption that cancer cells show increased activities of several metabolic processes (for review see Jager et al. [11]), and indeed, malignant transformation of cells has been found to be associated with increased metabolic activity [12]. High cell activity and cell turnover in cancer is assumed to be directly related to high activity of a variety of biological processes such as glycolysis, proliferation and membrane synthesis. Although the metabolic activity of PC is considered to be rather low because of its relatively low proliferative activity [13, 14], results obtained with metabolism-based tracers are promising. For imaging of PC, radiolabelled choline and acetate have been shown to be the most promising tracers [5, 15–19]. We selected choline as the metabolism-based reference tracer in this study to compare its imaging ability with that of the peptide receptor-based BN analogue AMBA.

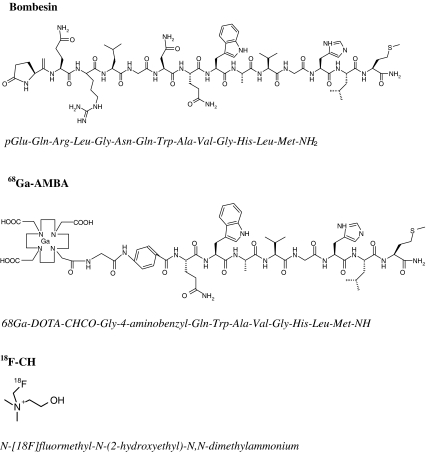

Choline is an essential nutrient that serves as a precursor for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, a major constituent of the cell membrane [20]. NMR spectroscopy has demonstrated higher concentrations of phosphocholine in human tumour tissues and in normal cells when stimulated by (mitogenic) growth factors [21, 22]. In PC the cellular uptake and phosphorylation of choline is often increased compared to normal prostate epithelial and stromal cells [23, 24]. Most PC imaging studies are PET scans using 11C-labelled choline [5, 15, 25, 26]. Since 11C has a relatively short half-life of 20 min, the use of this radionuclide is limited to centres with on-site cyclotrons. This drawback has led to the development of choline derivatives including N-[18F]-fluoromethyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-N,N-dimethylammonium (18F-FCH) with a radionuclide half-life of 110 min. The biodistribution of 18F-FCH is comparable to that of 11C-choline, although 18F-FCH shows higher renal activity [27]. The structures of BN, 68Ga-AMBA and 18F-FCH are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structural formulas of BN, 68Ga-AMBA and 18F-FCH

To compare the potential of these radioactive tracers, we used PC tumour-bearing male mice. The GRPR-expressing VCaP cell line is androgen-responsive, expresses the androgen receptor and secretes PSA, as do the majority of early- and late-stage PC, and is therefore a representative model for (progressive) human PC [28]. Since the androgen-independent, GRPR-expressing cell line PC-3 is the most widely used model for the study of radioactive BN analogues [8, 26, 29], this model was used as the reference model in this study. GRPR expression of both is comparable (data not shown).

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing BN analogue-based GRPR targeting and metabolism-based targeting for PC imaging. The PET imaging and biodistribution data of VCaP-bearing nude mice presented in this study show that peptide receptor-based targeting using 68Ga-AMBA for the GRPR is superior to metabolism-based targeting using 18F-FCH for detection of PC xenografts in nude mice.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human VCaP and PC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Lonza Verviers, Verviers, Belgium) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics (10,000 U/ml penicillin, 10,000 U/ml streptomycin; Lonza Verviers) with the addition of 10% fetal calf serum (Gibco Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for VCaP and 5% fetal calf serum for PC-3. Cells were grown in T175 Cellstar tissue culture flasks (Greiner Bio-One, Frickenhausen, Germany) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were passaged using a trypsin-EDTA solution (Lonza Verviers) containing 170,000 U/l trypsin-Versene and 200 mg/l EDTA. For the present study, cells were grown to near confluency, harvested and counted. Cells were resuspended in PBS to yield approximately 5 × 106 cells/100 μl for subcutaneous injection into nude mice.

PC xenografts

Eight male NMRI nu/nu mice (Taconic, Ry, Denmark) aged 6 to 7 weeks were inoculated subcutaneously with VCaP cells in the right shoulder. For reference, three mice were injected with PC-3 cells in the same way. A maximum of four mice were kept in individually ventilated cages measuring 14 × 13 × 33.2 cm (Techniplast) on sawdust (Woody-Clean, type BK8/15; BMI) under a 12-h light/dark cycle at 50 ± 5% relative humidity and a controlled temperature of approximately 22°C. Mice received irradiated chow and acidified drinking water ad libitum. Experiments were initiated when tumours reached a volume of 200–600 mm3 (2–5 weeks after inoculation).

This study was approved by the Animal Experimental Committee (DEC) of Erasmus MC and performed in agreement with The Netherlands Experiments on Animals Act (1977) and the European Convention for Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental Purposes (Strasbourg, 18 March 1986).

Radiolabelling and quality control

68Ga-DOTA-AMBA

Physical characteristics and radiochemistry of the 68Ge/68Ga generator

A 68Ge/68Ga 370-MBq generator (obtained from IDB Holland, Baarle Nassau, The Netherlands, and originating from iThemba Labs, Somerset West, South Africa) was used (t 1/2 68Ge 280 days, t 1/2 68Ga 68 min). The carrier used in this generator is SnO2. The generator was eluted with 1 M Ultrapure HCl 30% (J.T. Baker, Deventer, The Netherlands). All chemicals were of the highest grade available. The generator was eluted in the following fractions: 1.5 ml (void volume), 2.0 ml (80% of total activity) and 2.5 ml (waste). The fractions were collected and measured in a VDC-405 dose calibrator (Veenstra Instruments, Joure, The Netherlands). 68Ga was quantified as described previously [30]. Anion purification was performed with an Oasis WAX 1-cm3 column (Waters, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands). Before use the anion column was pretreated with 2 ml ethanol followed by 2 ml 5-M HCl. The total peak fraction (2 ml, about 300 MBq) was added to a 4-ml HCl solution (final concentration 5-M HCl). This solution was eluted over the anion column and subsequently washed with 2 ml of 5-M HCl containing 68Ge, which was then quantified. Approximately 0.4 ml of Milli-Q was used to desorp 68Ga (recovery ±80%).

Radiolabelling

DOTA-AMBA (MW 1,503 g/mol) was kindly provided by Prof. Dr. H.R. Maecke (University Hospital Basel, Switzerland). Before application of the peptide, it was dissolved in Milli-Q water (final concentration 10−3 M). Peptide, desorped 68Ga (200 μl in Milli-Q) and HEPES 1 M (200 μl) were heated for 10 min at 80°C. Radiolabelling was performed in reaction volumes of 1.5 ml in polypropylene or glass vials (Waters). The final pH of the radiolabelled product was in the range 3–3.5. The vials were placed on a temperature-controlled heating block. Instant thin-layer chromatography on silica gel was performed with a mobile phase comprising sodium citrate 0.1 M and ammonium acetate 1 M/methanol (1:1 v/v) [30, 31]. Activity was subsequently detected using a Packard Cyclone phosphor imaging system with OptiQuant software (PerkinElmer, Groningen, The Netherlands). HPLC quality control and purification were performed using a Waters breeze system with a 1525 binary HPLC pump. Radioactivity was detected with a Unispec MCA γ-detector (Canberra, Zelik, Belgium). For separation a Symmetry 5-μm, 4.6 × 250-mm C18 column (Waters) was used.

The HPLC mobile phase comprised 0.1% TFA (A) and methanol (B). The HPLC gradient was as follows: 0–2 min 100% A (flow 1 ml/min), 2–3 min 55% B (flow 0.5 ml/min), 3–20 min 60% B (flow 0.5 ml/min), 20–20:01 min 100% B (flow 1 ml/min), 20:01–25 min 100% A (flow 1 ml/min), and 25:01–30 min 100% A (flow 1 ml/min). The injection volume was 200 μ, and the injections were performed with a 717 autosampler (Waters).

After labelling, the main peak containing 68Ga-AMBA was collected carrier-free. Retention times were 12.4 min for DOTA-AMBA and 13.5 min for 68Ga-DOTA-AMBA. After quantification of the activity of the purified main peak the solution was diluted for injection (0.5–1.5 MBq per animal). Non-labelled DOTA-AMBA was added to obtain a solution containing a fixed mass (300 pmol). The 68Ga-DOTA-AMBA mass, collected by HPLC, was considered to be negligible (68Ga approximately 3.6 × 10−13 moles/37 MBq). After HPLC purification methionine, ascorbic acid and gentisic acid were added as quenchers for stabilization. The radiochemical purity was ±90%.

18F-Fluoromethyl-dimethyl-2-hydroxyethylammonium (18F-FCH)

Radiosynthesis and control of radiochemical purity were adapted from the methods described by Iwata et al. [32]. 18F-FCH was synthesized at the VU University Medical Centre (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). An remotely operated radiosynthesis system developed in-house was used. The 18F was isolated from 18O-enriched water through a PS-HCO3 ion-exchange column and was subsequently eluted into the reaction vial with 1 ml of a Kryptofix 2.2.2/K2CO3 solution (12.5 mg K2.2.2, 2 mg K2CO3 in acetonitrile/water 9:1 v/v). Under reduced pressure and a flow of helium (50 ml/min), the solvents were evaporated at 100°C. The residue was azeotropically dried by addition of 500 μl dry acetonitrile followed by evaporation as before. After cooling the reaction vial to room temperature followed by removal of the vacuum and helium, a dry solution of 50% dibromomethane in acetonitrile was added. The temperature was raised to 100°C, and the dibromomethane was allowed to react with the 18F for 5 min, after which the vial was again cooled to 35°C. 18F-Bromofluoromethane was then distilled from the vial using a stream of helium (50 ml/min) and passed through four connected Sep-Pak Plus silica cartridges and consecutively through an “on-column reaction” setup consisting of (1) a Sep-Pak Plus C18 cartridges loaded with 700 μl dimethylethanolamine, (2) a second Sep-Pak Plus C18 cartridge, and (3) an activated Sep-Pak Light Accell Plus CM ion-exchange cartridge connected in series. Activity on these cartridges was monitored and after it reached a maximum (8–12 min) distillation was terminated. The “on column reaction” setup was rinsed with 10 ml ethanol followed by 10 ml water and subsequently the 18F-FCH was eluted with 5 ml of 0.9% NaCl (aqueous) into a flask containing 10 ml of a 0.9% NaCl/7.09 mM NaH2PO4 (aqueous) solution yielding the final product.

PET scanning

Mice were anaesthetized with a mixture of isoflurane and oxygen, and were placed in the prone position and kept under anaesthesia in a MicroPET scanner (Inveon; Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN). Tumour-bearing mice were injected intravenously using a tail vein cannula with 300 pmol/100 μl 68Ga-AMBA (68Ga-AMBA: 1.5–0.5 MBq) or 100 μl 18F-FCH (8.1–1.2 MBq). Based on their unique pharmacokinetics an ideal scanning schedule for each tracer was constructed. So, a dynamic full-body acquisition was started at the time of injection for a continuous period of 30 min with 68Ga-AMBA or 20 min with 18F-FCH. During scanning the mice were kept warm with an external heating mat.

Each mouse was scanned after injection of the tracers 68Ga-AMBA and 18F-FCH on two consecutive days. In order to be able to correct for potential interference between the tracers, the first group of mice were scanned first with 68Ga-AMBA and 1 day later with 18F-FCH, and the remaining animals were scanned first with 18F-FCH and 1 day later with 68Ga-AMBA (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Time chart of the set up for PET and biodistribution studies

| Day | 68Ga–DOTA AMBA PET | 18F-FCH PET | 68Ga–DOTA-AMBA biodistribution | 18F-FCH biodistribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mice 1–4 | |||

| 2 | Mice 1–8 | Mice 1–4 | ||

| 3 | Mice 5–8 | Mice 5–8 |

List-mode data were stored on IAW 1.2.2.2 (Inveon Acquisition Workplace; Siemens). From there they were histogrammed and framed: 30×60-s frames for 68Ga-AMBA and 20×60-s frames for 18F-FCH. Attenuation correction on sinograms was subsequently performed. Images were reconstructed using filtered back projection (2DFBP) with a 50% ramp filter for analysis and quantification. For visualization the ordered-subsets expectation maximization/maximum a priori (OSEM3D/MAP) algorithm was used. To achieve steady-state for both quantification and visualization the sum of the last ten frames was displayed.

Quantification was performed by manually drawing volumes of interest (VOIs) over preselected organs (kidneys and bladder) and tumours in all directions with a VOI diameter not exceeding the total volume of the selected tissue to avoid interfering signals from other tissues [33]. The average outcomes from two independent skilled individuals were used. The percentage of injected dose per gram tissue (%ID/g) was calculated as VOI activity (in megabecquerels per millilitre)/total injected dose (in megabecquerels) × 100%. To decrease the interference from the background we allowed this uptake to wash out and quantified the mean total uptake at steady-state from the last 10 min of scanning in percent of injected dose per gram tissue. The median and interquartile range (IQR) in percent of injected dose per gram tissue were determined for the time points 0.5–30.0 min after injection. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Biodistribution studies

After PET scanning, VCaP tumour-bearing mice were killed for determination of biodistribution at ideal time points for each tracer. The biodistribution of 68Ga-AMBA was determined 1 h after injection and of 18F-FCH 30 min after injection following the schedule summarized in Table 1. Due to radiolysis, it was important to use 68Ga-AMBA immediately after labelling

Tumour, liver, heart, blood, muscle, tail and kidneys as well as the GRPR-expressing organs pancreas and colon [34], were collected for counting of radioactivity in a LKB-1282 Compugamma system (Perkin Elmer, Oosterhout, The Netherlands). Radioactive uptake was calculated as percent of injected dose per gram tissue after correction for remaining activity in the tail. Mean uptakes in each group of mice (N = 4) were then calculated.

The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. A probability of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

PET scanning

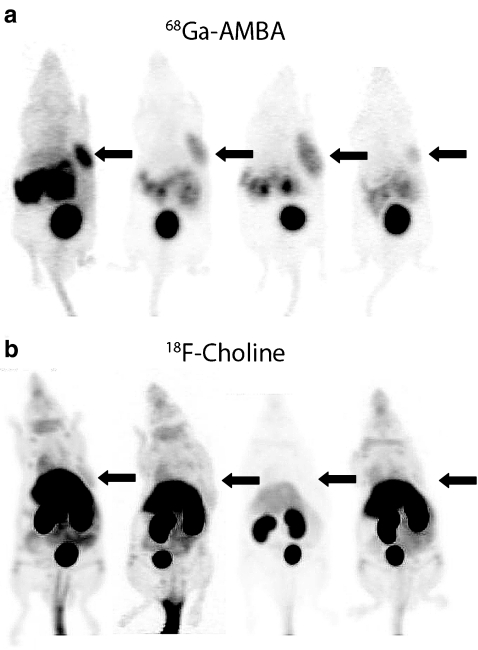

Using 68Ga-AMBA, all VCaP and PC-3 tumours were clearly visualized by PET. High uptake was seen in tumour tissue as well as in GRPR-positive pancreas tissue and in organs responsible for clearance (kidneys and bladder), while uptake in background organs was low (Fig. 2a). When performing PET scans using 18F-FCH it was more difficult to distinguish VCaP and PC-3 tumours from background tissues due to the relatively low tumour uptake and high uptake in surrounding background organs (Fig. 2b). In 20% of all 18F-FCH scans it was not possible to determine the tumour from background due to the poor contrast.

Fig. 2.

PET scans from four of eight corresponding VCaP-bearing mice: a scans after tail vein injection of 68Ga-AMBA (300 pmol, 1.5–0.5 MBq); b scans after tail vein injection of 18F-FCH (100 μl, 8.1–1.2 MBq). Using the OSEM3D/MAP algorithm the last ten frames of each scan were summed for image reconstruction. Arrows indicate tumour location

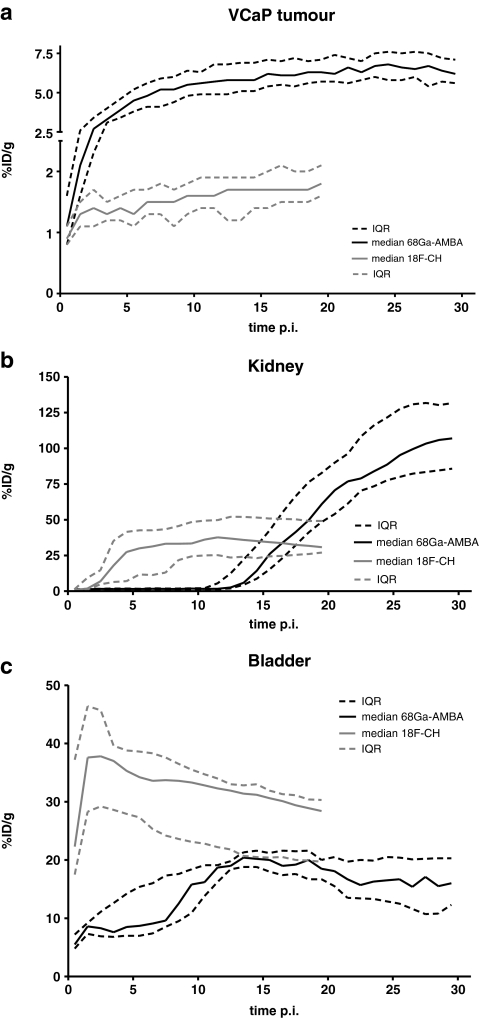

Dynamic tracer uptake in VCaP tumour, bladder and kidney over time is shown in Fig. 3. Tumour uptake of both tracers was fast, reaching peak values within 3–5 min. 68Ga-AMBA uptake reached a plateau phase at approximately 20 min after injection, while 18F-FCH uptake reached a plateau in less than 10 min (Fig. 3a). We used the average uptake in the plateau phase to calculate the total tumour uptake. In VCaP tumours, uptake was 6.7 ± 1.4%ID/g (N = 8) for 68Ga-AMBA, and only 1.6 ± 0.5%ID/g (N = 8) for 18F-FCH. This difference was highly significant (p <0.001). Similarly, for PC-3 tumours, uptake was 9.2 ± 1.1%ID/g (N = 3) for 68Ga-AMBA and 1.2 ± 0.3%ID/g (N = 3) for 18F-FCH. Renal clearance of 68Ga-AMBA gradually progressed over time resulting in accumulation of bladder radioactivity at 10 min after injection (Fig. 3b). Renal clearance of 18F-FCH occurred immediately after injection resulting in increased bladder radioactivity immediately after injection (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Uptakes in different tissues over time: a VCaP tumour (y-axis in two segments); b kidney; c bladder. Black solid lines show median uptake and black dashed lines IQR after tail vein injection of 68Ga-AMBA (300 pmol, 1.5–0.5 MBq, N = 8). Grey lines show median uptake and IQR after tail vein injection of 18F-FCH (100 μl, 8.1–1.2 MBq, N = 8)

Biodistribution studies

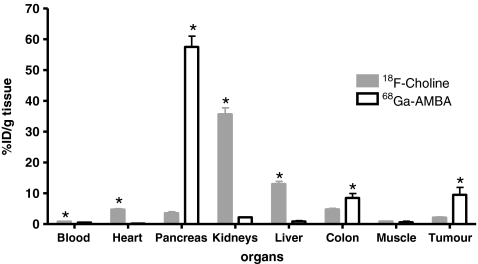

Biodistribution results are summarized in Fig. 4. Average VCaP tumour uptake of 68Ga-AMBA at 60 min after injection was 9.5 ± 4.8%ID/g and of 18F-FCH at 30 min after injection was 2.1 ± 0.4%ID/g (N = 4). These differences in tumour uptake were highly significant (p < 0.03).

Fig. 4.

Uptake in preselected organs after tail vein injection of both 68Ga-AMBA (300 pmol, 1.5–0.5 MBq) and 18F-FCH (100 μl, 8.1–1.2 MBq) in VCaP-bearing mice. Ex vivo biodistribution was determined 60 min after injection of 68Ga-AMBA and 30 min after injection of 18F-FCH. The results are presented as means ± standard deviation of four mice per tracer per time point. *p<0.05, 68Ga-AMBA vs. 18F-FCH

As was expected using GRPR-based tracers, the uptake of 68Ga-AMBA was high in the GRPR-positive pancreas (57.5 ± 7.1%ID/g), and that of 18F-FCH was much lower (3.6 ± 1.0%ID/g). The uptake of 68Ga-AMBA in the colon (8.5 ± 2.9%ID/g) was also significantly higher than that of 18F-FCH. On the other hand, the uptake of 18F-FCH in the kidneys was much higher (35.7 ± 4.1%ID/g) than that of 68Ga-AMBA (2.2 ± 0.2%ID/g). As in the kidney, most other (background) organs showed significantly higher uptake of 18F-FCH than 68Ga-AMBA: blood (0.8 ± 0.1 vs. 0.5 ± 0.1%ID/g tissue), heart (4.7 ± 0.5 vs. 0.2 ± 0.0%ID/g tissue) and liver (13.0 ± 1.7 vs. 0.9 ± 0.5%ID/g tissue). Only the uptake of 18F-FCH in muscle was not significantly different from that of 68Ga-AMBA (0.9 ± 0.2 vs. 0.7 ± 0.2%ID/g tissue). Both radiolabelled tracers showed low activity levels in blood.

Discussion

Accurate imaging of PC in patients is crucial for decision making as it strongly determines management of the disease. The accuracy of conventional imaging techniques is not adequate [4–6]. Nuclear scintigraphy is a promising modality for the sensitive imaging of PC. In this study we compared a peptide receptor-based tracer, the BN analogue AMBA, with a metabolism-based tracer, the choline derivative 18F-FCH, for targeting of PC.

In recent years, there has been a change of paradigm in the field of BN radiopharmaceuticals from agonists towards antagonists as potentially more favourable tracers for tumour targeting. Antagonists have been shown to wash out from the pancreas more rapidly than agonists and they seem to have a higher uptake and retention in PC [35]. Also antagonists have lower expected toxicity than the pharmacologically active agonists. In a previous study we indeed showed that the BN antagonist demobesin-1 was the best performing analogue of five compounds tested [10]. Nonetheless, in the same study AMBA also did well with a roughly comparable tumour uptake. Since it has a DOTA chelator AMBA can be labelled with the positron-emitting radionuclide 68Ga required for PET. This radionuclide can easily be obtained with an in-house generator. AMBA has been investigated in different preclinical and clinical studies already and can therefore serve as a model compound [8–10]. In the current study we decided to use BN analogue AMBA. In future studies it would also be interesting to investigate the targeting performance of BN antagonists for PET.

Although AMBA can be labelled with positron-emitting radionuclides, its use has yet not been reported in (animal) PET studies nor in studies in which it has been published labelled with 68Ga. Therefore, apart from our own experience with 68Ga-AMBA, the only available information to base an optimal PET protocol on came from studies using AMBA labelled with 177Lu or 111In. In a biodistribution study using 177Lu-DOTA-AMBA in PC-3-bearing mice, the animals were killed 1 h and 24 h after injection [9]. Absolute uptake was almost twice as high at the 1-h time point and overall tumour-to-background ratio was also favourable. In another study of the biodistribution in PC-bearing mice using 111In-DOTA-AMBA the mice were killed 1 h after injection only, and sufficient tumour uptake was shown [36]. In our standardized comparative study between different BN analogues, 111In-AMBA also showed high tumour uptake and promising tumour-to-background ratios at 1 h after injection [10]. Based on these data, and in order to be able to compare our data with those in the literature, we decided to determine the biodistribution of 68Ga-AMBA 1 h after injection. Imaging was initiated immediately after injection to provide an insight into the process of biodistribution of 68Ga-AMBA.

We used choline as the metabolism-based reference tracer in this study. Along with acetate, 11C-choline has been shown to be the most promising metabolism-based tracer for imaging of PC [5, 15–19]. In order to make the use of choline feasible for a large number of clinical centres that do not have a cyclotron, derivatives with a longer-lived radionuclide than the often employed 11C, such as 18F-FCH, were introduced by DeGrado et al. [27]. Experiments have shown that the rate of phosphorylation of this derivative by yeast choline kinase and its rate of uptake by cancer cells (PC-3) approach those of natural choline,. 18F-FCH can therefore be considered as a prototypical choline tracer. Since the biological processes of targeting are quite different, different protocol details are required for 18F-FCH and 68Ga-AMBA. Only a few PET imaging studies have been performed with radiolabelled choline in PC-bearing mice, so no consensus has been reached as to the optimal scanning protocol. Zheng et al. performed a PET study with 11C-choline in PC-3-bearing mice scanning one group for a 30 min and another for 60 min immediately after injection [26]. In a PET study using 11C-choline in TRAMP mice by Belloli et al., a 30-min acquisition was started immediately after injection [25], and in another study using 18F-FCH in xenograft-bearing mice, including mice bearing prostate DU145 tumours, by Ebenhan et al., acquisition was started at 15 min after injection [37]. Although sparse, dynamic data and reconstructions in all three studies implied that tumour uptake of choline is rapid and that choline uptake and tumour-to-background ratios do not improve when scanning is prolonged. Based on these data and our own pilot experiments (data not shown), we performed PET scans for 20 min starting immediately after injection of 18F-FCH. For determination of biodistribution, mice were killed at 30 min after injection, in accordance with the time point used for determination of biodistribution by Zheng et al. [26].

Comparison of tumour uptake in mice bearing VCaP and PC-3 xenografts has revealed that peptide-receptor targeting is superior to metabolism-based targeting in both tumour types. This may be explained by the fact that GRPR expression is high in these xenografts, while their metabolic activity is relatively low. Although choline uptake has been reported to increase with PC aggressiveness [4], in this study AMBA performed better in targeted tumour imaging of GRPR-expressing tumours. Also, while choline is taken up by all metabolizing organs, AMBA had much lower uptake in most non-targeted (GRPR-negative) organs. This was particularly visible when comparing PET images of the two types of tracer (Fig. 2). The high background signal observed with choline relates to the relative high metabolic activity in these organs due to general cellular processes that are not specifically related to cancer. Although, naturally, AMBA shows high background activity in GRPR-expressing tissues, peptide-receptor targeting is more tissue-specific than metabolism-based targeting. This resulted in more contrast between tumour and background, allowing more discrete imaging of GRPR-expressing tumour tissue.

Renal uptake and excretion of 18F-FCH is known to be higher than that of natural choline (11C-choline) [27]. High activity in the bladder resulting from this excretion could cause diagnostic limitations for the prostatic region [24, 38]. Zheng et al. reported kidney uptake of 5.1 ± 1.8%ID/g in PC-3-bearing athymic mice 30 min after injection of 11C-choline [26], while in our study the equivalent value was 35.7 ± 4.11%ID/g using 18F-FCH. More importantly, in our PET scans activity in the bladder was very high. The use of 11C-choline instead of 18F-FCH may reduce the undesirable high uptake in the kidneys and bladder while maintaining a tumour uptake comparable with that of 18F-FCH.

Dedicated PET for imaging of small animals is a very useful application in preclinical nuclear medicine research. Besides its use for establishing and validating novel tools for detection and visualization of tumours, PET data are also used for in vivo quantification. Quantification with PET allows the dynamics of biodistribution processes to be followed without the need for lots of laboratory animals for each time point. We determined tracer uptake in two different ways: first by analysis of PET images and, subsequently, by determining the biodistribution in tissues from the same animals. Quantification of in vivo PET data was in accordance with our ex vivo biodistribution results. The graphs showing tumour, kidneys and bladder uptake over time show the benefits of PET. Since spatial resolution of PET remains inferior to that of other imaging techniques such as CT, MRI and ultrasonography, dual modality scanners including PET/CT have been developed, and these provide accurate imaging [12, 39].

Time–activity curves derived from PET data showed that both imaging protocols used for scanning of AMBA and choline were well chosen. Especially for 18F-FCH, immediate imaging after injection was required, since tumour uptake was fast. Tumour uptake reached a plateau at the endpoint of both scanning protocols—which was 20 min after injection for 18F-FCH and 30 min after injection for 68Ga-AMBA—indicating that the dynamic process of tumour uptake did not require extended imaging.

In conclusion, the clinical diagnosis of (early) PC is a good application for targeted nuclear imaging of tumours based on receptor-specific radiolabelled analogues. PET imaging and biodistribution data indicated that tumour uptake of 68Ga-AMBA was higher while overall background activity was lower than observed for 18F-FCH in individual PC xenograft-bearing mice. These results suggest that peptide receptor-based targeting using BN analogues is superior to metabolism-based targeting using choline for scintigraphy of PC. The results of the present study indicate that further clinical evaluation of GRPR-targeted nuclear imaging of PC using BN-analogues is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Dutch Cancer Society for financial support (project number EMCR 2006-3555).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brawley OW. Prostate cancer screening; is this a teachable moment? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(19):1295–1297. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment after the introduction of prostate-specific antigen screening: 1986–2005. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(19):1325–1329. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellucci P, Fuccio C, Nanni C, Santi I, Rizzello A, Lodi F, et al. Influence of trigger PSA and PSA kinetics on 11C-choline PET/CT detection rate in patients with biochemical relapse after radical prostatectomy. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(9):1394–1400. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.061507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jana S, Blaufox MD. Nuclear medicine studies of the prostate, testes, and bladder. Semin Nucl Med. 2006;36(1):51–72. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu KK, Hricak H. Imaging prostate cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38(1):59–85. doi: 10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markwalder R, Reubi JC. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors in the human prostate: relation to neoplastic transformation. Cancer Res. 1999;59(5):1152–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder RP, van Weerden WM, Bangma C, Krenning EP, de Jong M. Peptide receptor imaging of prostate cancer with radiolabelled bombesin analogues. Methods. 2009;48(2):200–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lantry LE, Cappelletti E, Maddalena ME, Fox JS, Feng W, Chen J, et al. 177Lu-AMBA: synthesis and characterization of a selective 177Lu-labeled GRP-R agonist for systemic radiotherapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(7):1144–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder RP, Muller C, Reneman S, Melis ML, Breeman WA, de Blois E, et al. A standardised study to compare prostate cancer targeting efficacy of five radiolabelled bombesin analogues. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37(7):1386–1396. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1388-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jager PL, de Korte MA, Lub-de Hooge MN, van Waarde A, Koopmans KP, Perik PJ, et al. Molecular imaging: what can be used today. Cancer Imaging. 2005;5(Spec No A):S27–S32. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2005.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook GJ. Oncological molecular imaging: nuclear medicine techniques. Br J Radiol. 2003;76(Spec No 2):S152–S158. doi: 10.1259/bjr/16098061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Effert PJ, Bares R, Handt S, Wolff JM, Bull U, Jakse G. Metabolic imaging of untreated prostate cancer by positron emission tomography with 18fluorine-labeled deoxyglucose. J Urol. 1996;155(3):994–998. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofer C, Laubenbacher C, Block T, Breul J, Hartung R, Schwaiger M. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is useless for the detection of local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 1999;36(1):31–35. doi: 10.1159/000019923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Jong IJ, Pruim J, Elsinga PH, Vaalburg W, Mensink HJ. Preoperative staging of pelvic lymph nodes in prostate cancer by 11C-choline PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44(3):331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotzerke J, Volkmer BG, Glatting G, van den Hoff J, Gschwend JE, Messer P, et al. Intraindividual comparison of [11C]acetate and [11C]choline PET for detection of metastases of prostate cancer. Nuklearmedizin. 2003;42(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotzerke J, Volkmer BG, Neumaier B, Gschwend JE, Hautmann RE, Reske SN. Carbon-11 acetate positron emission tomography can detect local recurrence of prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29(10):1380–1384. doi: 10.1007/s00259-002-0882-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanni C, Castellucci P, Farsad M, Rubello D, Fanti S. 11C/18F-choline PET or 11C/18F-acetate PET in prostate cancer: may a choice be recommended? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34(10):1704–1705. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price DT, Coleman RE, Liao RP, Robertson CN, Polascik TJ, DeGrado TR. Comparison of [18F]fluorocholine and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose for positron emission tomography of androgen dependent and androgen independent prostate cancer. J Urol. 2002;168(1):273–280. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64906-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shindou H, Hishikawa D, Harayama T, Yuki K, Shimizu T. Recent progress on acyl CoA: lysophospholipid acyltransferase research. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S46–S51. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800035-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warden CH, Friedkin M. Regulation of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis by mitogenic growth factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;792(3):270–280. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(84)90194-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warden CH, Friedkin M. Regulation of choline kinase activity and phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis by mitogenic growth factors in 3T3 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(10):6006–6011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ackerstaff E, Pflug BR, Nelson JB, Bhujwalla ZM. Detection of increased choline compounds with proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy subsequent to malignant transformation of human prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61(9):3599–3603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwee SA, DeGrado TR, Talbot JN, Gutman F, Coel MN. Cancer imaging with fluorine-18-labeled choline derivatives. Semin Nucl Med. 2007;37(6):420–428. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belloli S, Jachetti E, Moresco RM, Picchio M, Lecchi M, Valtorta S, et al. Characterization of preclinical models of prostate cancer using PET-based molecular imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36(8):1245–1255. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng QH, Gardner TA, Raikwar S, Kao C, Stone KL, Martinez TD, et al. [11C]Choline as a PET biomarker for assessment of prostate cancer tumour models. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12(11):2887–2893. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeGrado TR, Baldwin SW, Wang S, Orr MD, Liao RP, Friedman HS, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of (18)F-labeled choline analogs as oncologic PET tracers. J Nucl Med. 2001;42(12):1805–1814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korenchuk S, Lehr JE, MClean L, Lee YG, Whitney S, Vessella R, et al. VCaP, a cell-based model system of human prostate cancer. In Vivo. 2001;15(2):163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaighn ME, Narayan KS, Ohnuki Y, Lechner JF, Jones LW. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3) Invest Urol. 1979;17(1):16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breeman WA, de Jong M, de Blois E, Bernard BF, Konijnenberg M, Krenning EP. Radiolabelling DOTA-peptides with 68Ga. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32(4):478–485. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1702-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decristoforo C, Knopp R, von Guggenberg E, Rupprich M, Dreger T, Hess A, et al. A fully automated synthesis for the preparation of 68Ga-labelled peptides. Nucl Med Commun. 2007;28(11):870–875. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e3282f1753d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwata R, Pascali C, Bogni A, Furumoto S, Terasaki K, Yanai K. [18F]Fluoromethyl triflate, a novel and reactive [18F]fluoromethylating agent: preparation and application to the on-column preparation of [18F]fluorocholine. Appl Radiat Isot. 2002;57(3):347–352. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(02)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buck AK, Herrmann K, Shen C, Dechow T, Schwaiger M, Wester HJ. Molecular imaging of proliferation in vivo: positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorothymidine. Methods. 2009;48(2):205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen RT, Battey JF, Spindel ER, Benya RV. International Union of Pharmacology. LXVIII. Mammalian bombesin receptors: nomenclature, distribution, pharmacology, signaling, and functions in normal and disease states. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60(1):1–42. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cescato R, Maina T, Nock B, Nikolopoulou A, Charalambidis D, Piccand V, et al. Bombesin receptor antagonists may be preferable to agonists for tumour targeting. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(2):318–326. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garrison JC, Rold TL, Sieckman GL, Naz F, Sublett SV, Figueroa SD, et al. Evaluation of the pharmacokinetic effects of various linking group using the 111In-DOTA-X-BBN(7-14)NH2 structural paradigm in a prostate cancer model. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19(9):1803–1812. doi: 10.1021/bc8001375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebenhan T, Honer M, Ametamey SM, Schubiger PA, Becquet M, Ferretti S, et al. Comparison of [18F]-tracers in various experimental tumour models by PET imaging and identification of an early response biomarker for the novel microtubule stabilizer patupilone. Mol Imaging Biol. 2009;11(5):308–321. doi: 10.1007/s11307-009-0216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greco C, Cascini GL, Tamburrini O. Is there a role for positron emission tomography imaging in the early evaluation of prostate cancer relapse? Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11(2):121–128. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4501028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buscombe JR, Bombardieri E. Imaging cancer using single photon techniques. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;49(2):121–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]