Summary

Previous studies have demonstrated that various type of stressors modulate messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) for type 1 corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor (CRH-R1 mRNA) and type 2 CRH receptor (CRH-R2 mRNA). The purpose of this study was to explore the effect of social isolation stress of varying durations on the CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary of socially monogamous female and male prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster). Isolation for 1 hr (single isolation) or 1 hr of isolation every day for 4 weeks (repeated isolation) was followed by a significant increase in plasma corticosterone levels. Single or repeated isolation increased hypothalamic CRH mRNA expression, but no changes in CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus were observed. Continuous isolation for 4 weeks (chronic isolation) showed no effect on hypothalamic CRH or CRH-R1 mRNAs in female or male animals. However, hypothalamic CRH-R2 mRNA was significantly reduced in voles exposed to chronic isolation. Single or repeated isolation, but not chronic isolation, significantly increased CRH-R1 mRNA and decreased CRH-R2 mRNA in the pituitary. Despite elevated CRH mRNA expression, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs were not modulated in the hippocampus following single or repeated isolation. Although, chronic isolation did not affect hippocampal CRH or CRH-R1 mRNAs, it did increase CRH-R2 mRNA expression in females and males. The results of the present study in prairie voles suggest that social isolation has receptor subtype and species-specific consequences for the modulation of gene expression for CRH and its receptors in brain and pituitary. Previous studies have revealed a female-biased increase in oxytocin in response to chronic isolation; however, we did not find a sex difference in CRH or its receptors following single, repeated or chronic social isolation, suggesting that sexually-dimorphic processes beyond the CRH system, possibly involving vasopressin, might explain this difference.

Keywords: CRH receptor, Social isolation

1. Introduction

Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is consider to be the major central regulator of the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) axis during stress (Whitnall, 1993). The biological actions of CRH are mediated through two types of receptor, designated CRH receptor type 1 (CRH-R1) and CRH receptor type 2 (CRH-R2) (Chang et al., 1993; Lovenberg et al., 1995; Perrin et al., 1995).

Studies in CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 deficient mice indicate that both types of receptors play an important but different roles in the activity of the HPA axis as well as in other functions (Reul and Holsboer, 2002). There is evidence that either CRH-R1 or CRH-R2 is important not only in maintenance of homeostasis but also in response to stress (Weninger et al., 1999; Reul and Holsboer, 2002). A possibility is that the two types of receptors are involved to a different degree in mediating behavioral responses to stress. Mice deficient in CRH-R1 display a decreased anxiety-like behavior and have an impaired stress response (Smith et al., 1998; Timpl et al., 1998); in contrast CRH-R2-mutant mice display an increased anxiety-like behavior and are hypersensitive to stress (Bale et al., 2000). A recent study in prairie voles demonstrated that following 4 days of separation from the female but not the male partner, experimental males displayed increased passive stress-coping. This effect was abolished by a nonselective CRH receptor antagonist, suggesting that both CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 were involved in the emergence of passive stress-coping behavior (Bosch et al., 2009). A study by Stowe and colleagues demonstrated that prairie and meadow voles differ dramatically in behavioral profiles, circulating CORT concentrations, and regional neuronal activation following an elevated plus maze test. Further, the influence of social isolation on anxiety-associated behaviors and neuronal activation markers is stimulus- and species-specific (Stowe et al., 2005).

The pituitary effects of CRH and family-related peptides depend not only on the hypothalamic output of CRH but also on the number of CRH receptors in the pituitary (Wang et al., 2004). The molecular mechanisms responsible for the behavioral and biochemical modifications in the animal brain are unknown. In this study, we compared the mRNA levels of genes involved in the isolation stress response in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and the pituitary of prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) subjected to isolation stress. Hypothalamus, pituitary and hippocampus were selected since they are described as particularly sensitive to the effects of stress and stress hormones (McEwen, 2001).

In the present study, we used the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster) as a model. This socially monogamous species exhibits characteristics that are similar to human behavior, including an active engagement in and reliance on the social environment, the formation of male-female pair bonds, display of biparental care, and a tendency to live in extended families (Carter et al., 1995; Carter, 2003; Keverne and Curley, 2004). It was shown that CRH appears to modulate pair bonding in prairie voles (DeVries et al., 2002). Previous work with this species has shown that prairie voles are affected by chronic isolation with increases in heart rate, reductions in parasympathetic activity, increases in behavioral indices of anxiety and depression and exaggerated reactivity to an acute stressor (Grippo et al., 2007d; 2007b). In addition, chronic isolation was associated with an increase in plasma oxytocin, although this increase was detected only in females. Recently, Bosch and colleagues found that following chronic isolation plasma corticosterone levels were elevated exclusively in males separated from the female-bonded partner (Bosch et al., 2009) supporting earlier reports that baseline corticosteroids are elevated following separation from a female partner in prairie voles (Carter et al, 1995). Either living with a familiar partner or being returned to a partner after isolation or exposure to other forms of stressors may ameliorate reactions to stressful experiences (Pournajafi-Nazarloo et al., 2009). However, mechanisms through which social experiences, including isolation, mediate stress reactivity remain poorly understood. One of the goals of the current study was to explore whether the sexes differ in the response to isolation stress of varying durations. Past and ongoing work from our group has found that male and female prairie voles differ in their responses to stressors, especially those in which separation from a familiar partner is a consequence of administering the stressor (Grippo et al., 2007b).

The purpose of this study was to examine in female and male prairie voles changes in the CRH system as a function of exposure to different types of challenge including a single, repeated or chronic social stressor (isolation). In this context, parameters of the CRH system were measured immediately following a stressor. Adult female and male prairie voles were housed with a same-sex sibling partner and then experienced (a) isolation for 1 hr, (b) 1 hr of social isolation every day for 4 weeks, (c) chronic social isolation for 28 days, (d) handling (HAN) without isolation, or (f) living PAIRED (animals left undisturbed with a same-sex sibling partner). Following these conditions blood samples and brain tissue were taken and frozen to allow subsequent measurements in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary of mRNA expression for CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2, using the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) method. Plasma levels of corticosterone also were measured for each animal.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals and general procedures

Animals used in this study were laboratory-bred female and male prairie voles that originated from wild stock trapped near Champaign, Illinois. Animals were maintained on a 14/10 h light/dark cycle in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment, and allowed food (Purina rabbit chow) and water ad libitum. Offspring (subjects) were housed with breeding pairs in large polycarbonate cages (45 cm long × 24 cm wide × 15 cm high) with cotton nesting material until 21 days of age when they were weaned and removed from the natal group and housed in same-sex sibling pairs in smaller (28 cm × 17.5 cm × 12 cm) cages until testing. Female prairie voles do not show an estrous cycle, instead requiring the presence of an unfamiliar male to induce ovarian activation. Thus females of this species remain reproductively inactive and can be studied without the complexity of ovarian cyclicity (Carter et al., 1995).

Animals in all conditions were housed in a single-sex colony rooms. Experimental procedures were carried out when female and males prairie voles were approximately 2 months of age, and ranged between 34-47 grams in body weight. Experimental subjects lived with a same-sex sibling in standard-sized cages following weaning and were randomly assigned to one of the treatments described below (n = 8 per group). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Following exposure to the experimental protocol, animals were deeply anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (67 mg/kg, sc; NLS Animal Health, Owings Mills, MD) and xylazine (13.33 mg/kg, sc; University of Illinois Hospital Pharmacy, Chicago, IL), followed by cervical dislocation. Blood was collected directly from the heart via a terminal bleed with a heparinized needle. Plasma was separated immediately by centrifugation at 4 °C and stored at -20 °C prior to corticosterone assay. The hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary were dissected on ice as described previously (Pournajafi-Nazarloo et al., 2009) and frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at -80°C prior to RNA extraction. All samples were collected during the lights on period between 1000h and 12000h.

2.2. Social isolation

Animals were subjected to single, repeated or chronic social isolation after living with a same sex sibling in a standard-sized cage since weaning. Social isolation involved removing the experimental animal from the home cage, and placing it into an isolated cage of the same size as the initial home cage. The animals were randomly divided into 3 groups (n = 8 per sex): Single isolation group; the paired animals were subjected to 1 hr of social isolation and then sacrificed. Repeated isolation group; the paired animals were subjected to 1 hr of social isolation every day for 4 weeks and then sacrificed immediately after the last isolation period. Chronic isolation group; the animals were subjected to 4 weeks of continuous social isolation and then sacrificed.

2.3. Handled or undisturbed control groups

Handled control (HAN) groups: paired animals were picked up and moved into new cages at the same time as the isolated group, and then were continually housed with their siblings for the length of the respective isolation period and then sacrificed. Paired control (PAIRED) groups; Paired animals remained undisturbed beyond routine husbandry, with their siblings for the length of the respective chronic isolation period and were then sacrificed.

2.4. Plasma corticosterone assay

All blood samples were placed on ice and centrifuged at 4 °C, 3500 rpm for 15 min. Plasma was stored at -20 °C prior to corticosterone assay using a commercially available radioimmunoassay kit (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) previously validated for the prairie vole (Taymans et al., 1997). The plasma was diluted in assay buffer as necessary (1:500) to give results reliably within the linear portion of the standard curve. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation for corticosterone are < 5%, and cross reactivity is < 1%.

2.5. RNA extraction

The total RNAs were extracted from each frozen hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary following published procedures (Auffray and Rougeon 1980) with slight modification. Briefly, each frozen tissue was homogenized in 5-10 ml LiCl-urea (3M LiCl, 6M urea) per g tissue and incubated overnight at 4°C. Homogenate was then centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 25 min. Supernatant was discarded and the walls of the tubes wiped with cotton swabs. Cold LiCl-urea was added to the tubes at half volume and the process repeated. Then the pellet was dissolved in half volume 10mM Tris pH 7.5, 1mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS. An equal volume of phenol:choloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) was added and vortexed. After centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min, the upper aqueous layer was transferred to the new tubes, and 100% ETOH was added to the each sample at 2x the volume, plus 10M of NH4OAc at 1/10x the volume and then mixed. Following precipitation and centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 25 min, the pellet was then been rinsed with 70% ETOH and re-suspended in 300μl diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated (DEPC) water. The amount of RNA was estimated by spectrophotometry at 260 nm and the integrity of RNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining.

2.6. cDNA synthesis and polymerase chain reaction amplification (RT-PCR)

cDNA synthesis and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification for CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs was performed using the ThermalCycler PCR as described previously (Pournajafi-Nazarloo et al., 2007b, 2003). Briefly, total RNA (3 μg) was combined with 25 pmol oligo-d(T) primer, 0.5 μl RNAse inhibitor, and brought to a total volume of 12 μl using DEPC water. The samples were heated for 10 min at 70°C, chilled on ice for 5 min, and then quickly centrifuged. To this mixture, 4 μl Superscript 5X first-strand buffer, 2 μl 0.1M DTT, and 1 μl 10mM dNTP mix (Roche #1 969 064) were added. The samples were heated at 37°C for 2 min and 1 μl of Superscript RT added. This mixture was incubated at 42°C for 1 hr and then enzymes denatured by heating for 10 min at 95°C. The RT reaction was diluted 1:10 with DEPC water for PCR reaction. Exactly half of the first strand cDNA synthesis of each sample was used for PCR amplification, using primers designed to span at least one intron (to ensure cDNA and not contaminating genomic DNA is amplified). PCR was performed in a total reaction volume of 100 μl containing oligonucleotide primers (0.2 μM), 1 × PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCL, 50 mM KCl, pH 8.3), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 m/m dNTPs, and 2.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase. The specific primers used were CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 and β-actin, a ‘house-keeping’ gene used to determine the constitutive level of gene transcription and to control for variations in RNA recoveries. The sequence of specific primers was chosen based on a previous study (Pournajafi-Nazarloo et al., 2007a). The reaction mixture was incubated in the thermal cycler for 32-35 cycles as follows: at 94°C for 90 s, at 57°C for 60 s and at 72°C for 60 s. The cycles were terminated on the phase during which there was exponential generation of PCR product before reaching a plateau. When the cycles were completed, the tubes were maintained at 72°C for 5 min. Negation of contaminated genomic DNA was performed by analyzing the absence of templates in control samples without reverse transcriptase. Sequence analysis was performed to confirm the identity of the amplified cDNA.

2.7. Quantification of RT-PCR products

The RT-PCR method used in these assays is semi-quantitative because absolute values of mRNA levels could not be determined since internal controls for the specific mRNAs were not used. To validate this RT-PCR assay as a tool for the semi-quantitative measurement of mRNA, dose–response curves were established for different amounts of total RNA extracted from the hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary, and the samples were quantified in the curvilinear phase of PCR amplification. The expression levels were normalized against β-actin. No difference was observed in β-actin levels at any stage. 10 μl of the PCR product was analyzed on 0.8% agarose gel with ethidium bromide. RT-PCR amplification of CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary revealed PCR products of the expected base pair length for each primer. The quantification of RT-PCR products was performed by densitometric analysis of photographic negatives of agarose gels using NIH Image and then the ratios of CRH, CRH-R1 or CRH-R2 /β-actin were calculated.

2.8. Statistics

Data are presented as the mean±S.E.M. Statistical comparisons were made using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A level of p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Plasma corticosterone levels

We found no effect of handling (HAN) on plasma corticosterone levels compare to PAIRED groups in female or male prairie voles. Single or repeated isolation was followed by an increase in plasma corticosterone levels in female and male [F(9,70) = 2.933, P < 0.05] prairie voles, when compared to HAN groups. However, following chronic isolation plasma corticosterone level was returned to basal level in both sexes. No significant differences were observed in plasma corticosterone level between female and male animals within the same groups (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of single, repeated or chronic isolation on plasma corticosterone level of female and male prairie voles. Data represent the means ± SEM (n=8 per treatment group for each sex). * represents significant differences at p<0.05, when compared to HAN groups for each sex.

3.2. CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression in the hypothalamus

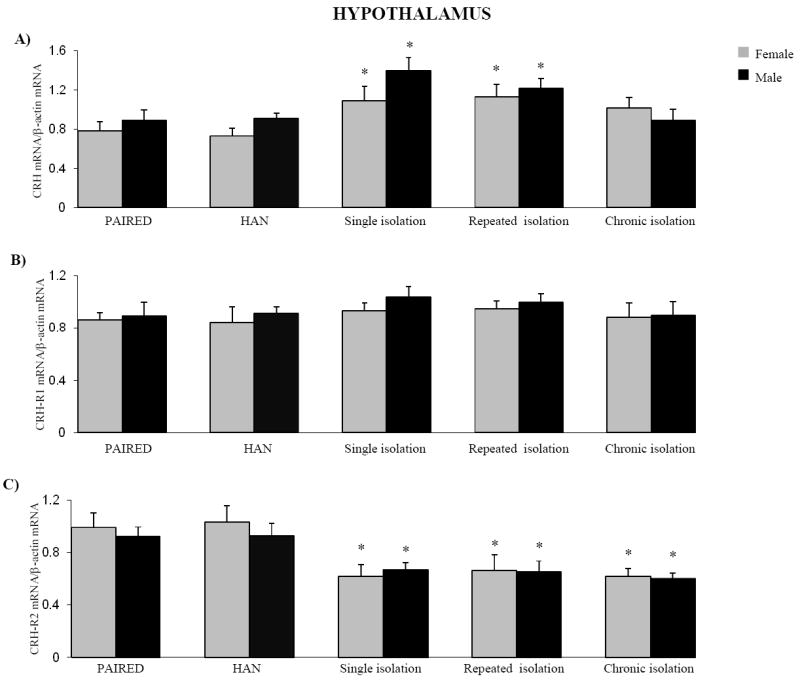

Fig. 2 shows mRNA expression for CRH (panel A), CRH-R1 (panel B) and CRH-R2 (panel C) in the hypothalamus of prairie voles. Single or repeated isolations was associated with a significant increases in hypothalamic CRH mRNA expression in female and male animals [F(9,70) = 2.689, P < 0.05] when compared to the HAN group (fig. 2A). Prairie voles showed no changes of CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus following single, repeated or chronic social isolation (fig. 2B). Single or repeated isolation was associated with a significant decrease in hypothalamic CRH-R2 mRNA expression in female and male animals [F(9,70) = 2.987, P < 0.05] when compared to HAN group. Chronic social isolation down-regulated the hypothalamic CRH-R2 mRNA in female and male animals [F(9,70) = 2.987, P < 0.05] compared to PAIRED group (fig. 2C). In both female and male groups handling (HAN) produced no effect on mRNA expression for the hypothalamic CRH or its receptors compare to PAIRED groups. We found no significant differences in hypothalamic CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression between female and male prairie voles within the same groups (fig. 2A-C).

Figure 2.

Effect of single, repeated or chronic isolation on CRH mRNA (A), CRH-R1 mRNA (B) and CRH-R2 mRNA expression (C) in the hypothalamus of female and male prairie voles. Data represent the means ± SEM (n=8 per treatment group for each sex). * represents significant differences at p<0.05, when compared to HAN groups for each sex.

3.3. CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression in the hippocampus

Fig. 3 shows mRNA expression for CRH (panel A), CRH-R1 (panel B) and CRH-R2 (panel C) in hippocampus of prairie voles. Single or repeated isolation produced a significant increase in hippocampal CRH mRNA expression in female and male animals [F(9,70) = 2.864, P < 0.05] when compared to HAN group (fig. 3A). No effect of single, repeated or chronic isolation was seen on mRNA expression for hippocampal CRH-R1 in female and male animals, when compared to HAN or PAIRED groups (fig. 3B). The chronic isolation was associated with a significant increase in hippocampal CRH-R2 mRNA in female and male animals [F(9,70) = 2.991, P < 0.05] when compared to PAIRED group (fig. 3C). Handling (HAN) produced no effect on mRNA expression for the hippocampal CRH or its receptors in female and male animals compare to PAIRED groups. No significant differences were detected in hippocampal CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression between female and male prairie voles within the same groups (fig. 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Effect of single, repeated or chronic isolation on CRH mRNA (A), CRH-R1 mRNA (B) and CRH-R2 mRNA expression (C) in the hippocampus of female and male prairie voles. Data represent the means ± SEM (n=8 per treatment group for each sex). *, ** represent significant differences at p<0.05 and p<0.01, respectively, when compared to HAN groups for each sex.

3.4. CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression in the pituitary

Fig. 4 shows mRNA expression for CRH-R1 (panel A) and CRH-R2 (panel B) in pituitary of prairie voles. Although, chronic isolation stress produced no effect on did not affect CRH receptor mRNA expression, single or repeated isolations were associated with a significant increases in CRH-R1 in female and male animals compared to HAN groups. Single or repeated isolation decreased CRH-R2 mRNAs expression in the pituitary of female and male animals [F(9,70) = 2.838, P < 0.05], when compared to HAN groups (fig. 4A, B). Handling (HAN) produced no effect on mRNA expression for CRH receptors in the pituitary of female and male animals compare to PAIRED groups. We found no significant differences in the pituitary CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs expression between female and male prairie voles within the same groups (fig. 4A, B).

Figure 4.

Effect of single, repeated or chronic isolation on CRH-R1 mRNA (A) and CRH-R2 mRNA expression (B) in the pituitary of female and male prairie voles. Data represent the means ± SEM (n=8 per treatment group for each sex). * represent significant differences at p<0.05, when compared to HAN groups for each sex.

4. Discussion

Results from the present study revealed that mRNA expression for the CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 in the hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary differed as a function of exposure to single, repeated or chronic social isolation in female and male prairie voles. Following single and repeated isolation significantly higher levels of CRH mRNA expression were detected in hypothalamus and hippocampus, although no change was detected in the expression of CRH-R1 mRNA. In pituitary, both females and male exposed to single, repeated isolation exhibited increased CRH-R1 mRNA expression and decreased CRH-R2 mRNA expression. In contrast, animals exposed to chronic isolation exhibited a reduction of CRH-R2 mRNA expression in hypothalamus and an elevation of CRH-R2 mRNA expression in the hippocampus, with no change in pituitary. No sex differences were detected in any measure.

We found that single as well as repeated isolation increased plasma corticosterone level and following chronic isolation plasma corticosterone was returned to basal level. In previous studies form our laboratory and others, it has been observed that short-term separation from a sibling increased basal levels of corticosterone in 40-day-old female prairie voles (Kim and Kirkpatrick, 1996) as well as in juvenile voles of both sexes (Ruscio et al., 2007). Thus, it seems that in adult female voles the loss of social support by a conspecific partner of the same sex has strong physiological (Kim and Kirkpatrick, 1996) and emotional (Grippo et al, 2007a, b) effects, whereas in males the loss of a bonded female partner results in alterations of these parameters (Bosch et la., 2009). The failure to detect an increase of plasma corticosterone in the chronic situation could reflect an adaptation to the isolation experience; this is supported by a previous study from this laboratory (Grippo et al., 2007d). However, the results of the latter study also demonstrated that corticosterone responses in isolated animals were more reactive than in paired animals following exposure to an acute social stressor. Thus, the physiological capacity to respond to a challenge remained intact during chronic isolation.

The modulation of CRH and its receptors following stress is stressor-specific and also brain-region specific (Imaki et al., 1991). In the present study, following single or repeated isolation, no changes in hypothalamic CRH-R1 mRNA were observed, although single or repeated isolation resulted in a significant increase in hypothalamic CRH mRNA expression. In the present study, 4 weeks of separation from the partner presumably acted as a chronic stressor, with neuroendocrine changes that differed from those following short-term separation. Based on research in other rodents, during chronic stress arginine-vasopressin (AVP) appears to become the predominant regulator of HPA function (Aguilera, 1994) whereas CRF mRNA expression may adapt to or remain unchanged, depending on the stressor (Aguilera and Rabadan-Diehl, 2000).

Exposure to acute or chronic stressors is known to cause an up-regulation of CRH mRNA in the rat paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of hypothalamus, which is responsible for the activation of the HPA axis (Drolet and Rivest, 2001). Previously, using CRH deficient (CRH KO) and wild type (WT) mice, we reported that WT mice showed an increase in CRH mRNA in the hypothalamus following a 2-h restraint stress, but failed to show an elevation in hypothalamic CRH-R1 mRNA (Makino et al., 2005), consistent with results from others (Imaki et al., 2003). In rats, it has been demonstrated that both CRH and CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus are up-regulated by various types of stressors (Makino et al., 1995). Central administration of CRH increased CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus, and the effect of CRH was blocked by alpha-helical CRH (Imaki et al., 2003). Direct infusion of CRH into the dorsal PVN was also shown to induce CRH-R1 mRNA in CRH-positive neurons in the parvocellular part of the PVN (Imaki et al., 2003), suggesting that CRH increases the amplitude of its own response to stress by increasing the number of CRH-R1 receptors in the hypothalamus of rats (Ono et al., 1985).

In the current study in voles, no stress-related changes of CRH-R1 mRNA were observed in the hypothalamus, although single as well as repeated isolation resulted in a statistical significant increase in plasma corticosterone level. It was reported that the increase in CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus was higher in adrenalectomized rats than in sham-operated rats following single or repeated immobilization stress (Makino et al., 1995), suggesting that elevated corticosterone during stress impairs the changes of CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus. Further, we have observed that adrenalectomized WT mice mimicked the restraint stress-induced increase in CRH-R1 mRNA in the hypothalamus reported in CRH KO mice. Both CRH KO and adrenalectomized WT mice fail to show an elevation of plasma corticosterone during stress (Makino et al., 2005) suggesting that PVN CRH-R1 mRNA is negatively regulated by glucocorticoids in mice. Taken together, up-regulation of hypothalamic CRH-R1 mRNA following stress in rat but not in prairie voles may supports the hypothesis that the regulation of CRH-R1 gene transcription is species specific.

Lovenberg and colleagues demonstrated that CRH-R2 is highly expressed in the rat hypothalamus (Lovenberg et al., 1995). We found that single, repeated and chronic social isolation were associated with a significant reduction in the hypothalamic CRH-R2 mRNA expression. Previous studies in mice showed that following acute restraint stress the hypothalamic CRH-R2 levels were decreased. Further, after 9 days of chronic stress, a significant decrease in the CRH-R2 transcript levels was found (Chen et al., 2005). Moreover, in mice it has been reported that hypothalamic CRH-R2α receptor gene transcription can be inhibited by glucocorticoid administration in vivo and in vitro (Ono et al., 1985). In contrast, in rats CRH-R2 mRNA levels in ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) were increased after a high dose of corticosterone administration, while adrenalectomy induced a reduction of CRH-R2 mRNA levels (Makino et al., 1998). The same study also reported that the levels of CRH-R2 mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus were not influenced by corticosterone administration or adrenalectomy, suggesting that these receptors are differentially regulated in different hypothalamic nuclei. Taken together these studies indicate that the regulation of CRH receptors in the hypothalamus is both region and species-specific.

The present investigation showed that within the pituitary of prairie voles, although chronic isolation produced no effect on CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA expression, single or repeated isolation was followed by modulation of both CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNA expression. These findings are in agreement with previous research in which CRH-R2 mRNA levels in the pituitary were significantly decreased after restraint stress in prairie voles and rats (Kageyama et al., 2003; Pournajafi-Nazarloo et al., 2009). Immobilization stress for 2 hr decreased CRH-R1 mRNA expression and immobilization stress for 8 hr increased CRH-R1 mRNA expression in rats (Rabadan-Diehl et al., 1996). It was suggested that stress-activated circulating glucocorticoids might be one of the factors involved because administration of dexamethasone or corticosterone caused a significant decrease in CRH receptor mRNA levels in the rat pituitary (Makino et al., 1995). It was found that chronic and repeated immobilization increased CRH receptor mRNA in the rat pituitary (Rabadan-Diehl et al., 1996). It appears, therefore, that a feature of CRH receptor mRNA responsiveness to stress is not only dependent on the stimulating-intensity and time-course but also on the type of stressor. The mechanism by which different types of stressors differentially regulate CRH-R1 mRNA and CRH-R2 mRNA levels is not clear. However since stress increases pituitary exposure to hypothalamic CRH and AVP, and circulating corticosteroids (Aguilera et al., 2001), an interaction between the CRH family peptides, AVP and corticosterone has to be considered for the modulation of CRH receptor mRNA in the pituitary.

The CRH and its receptors are also expressed in other brain regions, including the hippocampus, where CRH acts as a neurotransmitter or neuromodulator (Heinrichs and Koob 2004). To determine whether the hippocampus is involved in the acute or chronic stress response, we investigated whether stressful social isolation influenced the expression of hippocampal CRH, CRH-R1 and CRH-R2 mRNAs. Data from the present study revealed that single or repeated isolation increased CRH mRNA in the hippocampus. Other kinds of stressors are reported to induce an increase in hippocampal CRH. For example, in rats, exposure to acute immobilization stress induced an increase in hippocampal CRH mRNA (Chen et al., 2004). Acute psychological stress activates hippocampal CRH-R1 probably through locally-secreted CRH (Givalois et al., 2000). The physiological consequences of the increase in hippocampal CRH levels in prairie voles are unclear because its function is not clearly understood. We also detected a trend toward an increase in CRH-R1 expression, although the difference with the handling group (control) did not reach statistical significance. In the adult hippocampus, contrasting findings were reported, depending on stimulus type and time course. After chronic unpredictable stress, an increase in CRH-R1 mRNA was detected in adult rat hippocampus, which was not observed after acute restraint stress (Iredale et al., 1996). In contrast, in gerbil hippocampus, spontaneous seizures acutely induced a decrease in CRH-R1 immunoreactivity, which recovered after 24 h (An et al., 2003).

Although, single or repeated isolation produced no effect on CRH-R2 mRNA expression in the hippocampus, chronic isolation was followed by increased CRH-R2 mRNA expression. It was reported that the CRH-R2 gene was significantly up-regulated 3 hr after the end of stressful immobilization (Sananbenesi et al., 2003). In addition, it has been shown that the role of CRH receptors in associative learning depends on their regional interactions with other G-protein-coupled receptors (Radulovic et al., 2000). It can be expected, therefore, that CRH-R2 may activate distinct molecular pathways in different brain areas. This view is consistent with earlier observations showing selective regional alterations of cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation in the forebrain of mice lacking CRH-R2 (Bishop et al., 2006) that involved the amygdala but not the hippocampus. Since the abundance of the two CRH receptor subtypes is regionally specific, the involvement of CRH-R2 in anxiety may involve brain regions other than those examined in the present investigation.

Unlike our previous work (Pournajafi Nazarloo, et al., 2009), both female and male voles are included in the current study. One of the goals of the current study was to explore whether the sexes differ in the response to isolation stress of varying durations. Past and ongoing work from our group has found that male and female prairie voles differ in their responses to stressors, especially those in which separation from a familiar partner is a consequence of administering the stressor (Grippo et al., 2007b). Continued examination of sex differences in the response to stressors is important because many disorders that involve emotional dysregulation and/or deficits in social behavior differentially affect one sex more than the other. However, data from the current study did not reveal any sex differences in the response to varying durations of social isolation. In addition, previous work has shown differences between restrained vs. un-restrained voles. Physical restraint involves two theoretically distinct sources of psychological aversiveness for the “highly social” prairie vole – (1) separation from its familiar partner, and (2) the inability to move freely in an enclosed space, mimicking the naturalistic experience of burrow collapse. One of the goals of the current study was to separate between these two influences and isolate the effect of social separation by subjecting voles to separation from their familiar partner without introducing the confound of physical restraint.

Clarification of the precise mechanisms through which neuroendocrine cues, especially those influenced by different type of stressors, regulate CRH and its receptors is an important area for future investigation. These studies also support the usefulness of the prairie vole as a model for studies of the role of social interactions and isolation in CNS function. Finally both CRH receptor mRNAs in different regions of brain and pituitary are modulated by single or repeated isolation, but CRH-R2 mRNA appears to be more involved in chronic social isolation.

In conclusion, these results indicate that the responses to acute versus chronic stressors are regulated through different central mechanisms, including brain region-specific and species-specific actions of different CRH receptors. Peripheral measurements of oxytocin have suggested that male and female prairie voles differ in their response to chronic isolation, with only females showing an isolation-associated increase in oxytocin (Grippo et al., 2007a, 2007b). However, the results of the present study did not reveal sex differences in gene expression for CRH or CRH receptors in either the brain or pituitary. These results suggest for future study the hypothesis that chronic stressors may differentially affect AVP or other sexually dimorphic processes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development HD68987 (CSC) and National Institute of Mental Health MH073022 (CSC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aguilera G. Regulation of pituitary ACTH secretion during chronic stress. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1994;15:321–350. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G, Rabadan-Diehl C. Vasopressinergic regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis: implications for stress adaptation. Regul Pept. 2000;96:23–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera G, Rabadan-Diehl C, Nikodemova M. Regulation of pituitary corticotropin releasing hormone receptors. Peptides. 2001;22:769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An SJ, Park SK, Hwang IK, Kim HS, Seo MO, Suh JG, Oh YS, Bae JC, Won MH, Kang TC. Altered corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) receptor immunoreactivity in the gerbil hippocampal complex following spontaneous seizure. Neurochem Int. 2003;43:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffray C, Rougeon F. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned cDNA corresponding to secreted mu chain of mouse immunoglobulin. Eur J Biochem. 1980;107:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(80)90017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL, Contarino A, Smith GW, Chan R, Gold LH, Sawchenko PE, Koob GF, Vale W, Lee KF. Mice deficient for corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2 display anxiety-like behaviour and are hypersensitive to stress. Nat Genet. 2000;24:410–414. doi: 10.1038/74263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop GA, Tian JB, Stanke JJ, Fischer AJ, King JS. Evidence for the Presence of the Type 2 Corticotropin Releasing Factor Receptor in the Rodent Cerebellum. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:1255–1269. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, Nair HP, Ahern TH, Neumann ID, Young LJ. The CRF System Mediates Increased Passive Stress-Coping Behavior Following the Loss of a Bonded Partner in a Monogamous Rodent. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1406–1415. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS. Developmental consequences of oxytocin. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:383–397. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, DeVries AC, Getz LL. Physiological substrates of mammalian monogamy: the prairie vole model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995;19:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00070-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CP, Pearse RI, O’Connell S, Rosenfeld MG. Identification of a seven transmembrane helix receptor for corticotropin-releasing factor and sauvagine in mammalian brain. Neuron. 1993;11:1187–1195. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90230-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Brunson KL, Adelmann G, Bender RA, Frotscher M, Baram TZ. Hippocampal corticotropin releasing hormone: pre- and postsynaptic location and release by stress. Neuroscience. 2004;126:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Perrin M, Brar B, Li C, Jamieson P, DiGruccio M, Lewis K, Vale W. Mouse Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Receptor Type 2α Gene: Isolation, Distribution, Pharmacological Characterization and Regulation by Stress and Glucocorticoids. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:441–458. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, Guptaa T, Cardillo S, Cho M, Carter CS. Corticotropin-releasing factor induces social preferences in male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:705–714. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drolet G, Rivest S. Corticotropin-releasing hormone and its receptors; an evaluation at the transcription level in vivo. Peptides. 2001;22:761–767. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givalois L, Arancibia S, Tapia-Arancibia L. Concomitant changes in CRH mRNA levels in rat hippocampus and hypothalamus following immobilization stress. Mol Brain Res. 2000;75:166–171. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Cushing BS, Carter CS. Depression-like behavior and stressor-induced neuroendocrine activation in female prairie voles exposed to chronic social isolation. Psychosom Med. 2007a;69:149–157. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802f054b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Gerena D, Huang J, Kumar N, Shah M, Ughreja R, Carter CS. Social isolation induces behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances relevant to depression in female and male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007b;32:966–980. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Cardiac regulation in the socially monogamous prairie vole. Physiol Behav. 2007c;90:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Social isolation disrupts autonomic regulation of the heart and influences negative affective behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2007d;62:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs SC, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor in brain: a role in activation, arousal, and affect regulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311:427–440. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaki T, Katsumata H, Konishi S, Kasagi Y, Minami S. Corticotropin-releasing factor type-1 receptor mRNA is not induced in mouse hypothalamus by either stress or osmotic stimulation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:916–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaki T, Nahan JL, Rivier C, Sawchenko PE, Vale W. Differential regulation of corticotropin-releasing factor mRNA in rat brain regions by glucocorticoids and stress. J Neurosci. 1991;11:585–599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iredale PA, Terwilliger R, Widnell KL, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Differential regulation of corticotropin-releasing factor 1 receptor expression by stress and agonist treatments in brain and cultured cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;50:1103–1110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama K, Li C, Vale WW. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 2 messenger ribonucleic acid in rat pituitary: localization and regulation by immune challenge, restraint stress, and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1524–1532. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keverne EB, Curley JP. Vasopressin, oxytocin and social behaviour. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Kirkpatrick B. Social isolation in animal models of relevance to neuropsychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:918–922. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW, Liaw CW, Grigoriadis DE, Clevenger W, Chalmers DT, De Souza EB, Oltersdorf T. Cloning and characterization of a functionally distinct corticotropin-releasing factor receptor subtype from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:836–840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Nishiyama M, Asaba K, Gold PW, Hashimoto K. Altered expression of type 2 CRH receptor mRNA in the VMH by glucocorticoids and starvation. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1138–R1145. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Schulkin J, Smith MA, Pacak K, Palkovits M, Gold PW. Regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in the rat brain and pituitary by glucocorticoids and stress. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4517–4525. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Tanaka Y, Pournajafi Nazarloo H, Noguchi T, Nishimura K, Hashimoto K. Expression of type 1 corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor mRNA in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus following restraint stress in CRH-deficient mice. Brain Res. 2005;1048:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Plasticity of the hippocampus: adaptation to chronic stress and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;933:265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono N, Bedran De Castro JC, McCann SM. Ultrashort-loop positive feedback of corticotropin (ACTH)-releasing factor to enhance ACTH release in stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:3528–3531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.10.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin M, Donaldson C, Chen R, Blount A, Berggren T, Bilezikjian L, Sawchenko P, Vale W. Identification of a second corticotropin-releasing factor receptor gene and characterization of a cDNA expressed in heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2969–2973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Partoo L, Sanzenbacher L, Azizi F, Carter CS. Modulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone type 2 receptor and urocortin 1 and urocortin 2 mRNA expression in the cardiovascular system of prairie voles following acute or chronic stress. Neuroendocrinology. 2007a;86:17–25. doi: 10.1159/000103587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Partoo L, Sanzenbacher L, Paredes J, Hashimoto K, Azizi F, Carter CS. Stress differentially modulates mRNA expression for corticotrophin-releasing hormone receptors in hypothalamus, hippocampus and pituitary of prairie voles. Neuropeptides. 2009;43:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Perry A, Partoo L, Papademeteriou E, Azizi F, Carter CS, Cushing BS. Neonatal oxytocin treatment modulates oxytocin receptor, atrial natriuretic peptide, nitric oxide synthase and estrogen receptor mRNAs expression in rat heart. Peptides. 2007b;28:1170–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournajafi Nazarloo H, Tanaka Y, Dorobantu M, Hashimoto K. Modulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 2 mRNA expression by CRH deficiency or stress in the mouse heart. Regul Pept. 2003;115:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(03)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabadan-Diehl C, Kiss A, Camacho C, Aguilera G. Regulation of messenger ribonucleic acid for corticotropin releasing hormone receptor in the pituitary during stress. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3808–3814. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic J, Fischer A, Katerkamp U, Spiess J. Role of regional neurotransmitter receptors in corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-mediated modulation of fear conditioning. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:707–710. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reul JM, Holsboer F. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors 1 and 2 in anxiety and depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(01)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio MG, Sweeny T, Hazelton J, Suppatkul P, Carter CS. Social environment regulates corticotropin releasing factor, corticosterone and vasopressin in juvenile prairie voles. Horm Behav. 2007;51:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sananbenesi F, Fischer A, Schrick C, Spiess J, Radulovic J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the hippocampus and its modulation by corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2: a possible link between stress and fear memory. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11436–11443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11436.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GW, Aubry JM, Dellu F, Contarino A, Bilezikjian LM, Gold LH, Chen R, Marchuk Y, Hauser C, Bentley CA, Sawchenko PE, Koob GF, Vale W, Lee KF. Corticotropin releasing factor receptor 1-deficient mice display decreased anxiety, impaired stress response, and aberrant neuroendocrine development. Neuron. 1998;20:1093–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe JR, Liu Y, Curtis JT, Freeman ME, Wang Z. Species differences in anxiety-related responses in male prairie and meadow voles: The effects of social isolation. Physiology & Behavior. 2005;86:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans SE, DeVries AC, DeVries MB, Nelson RJ, Friedman TC, Castro M, Detera-Wadleigh S, Carter CS, Chrousos GP. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis of prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster): evidence for target tissue glucocorticoid resistance. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1997;106:48–61. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1996.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpl P, Spanagel R, Sillaber I, Kresse A, Reul M, Stalla GK, Blanquet V, Steckler T, Holsboer F, Wurst W. Impaired stress response and reduced anxiety in mice lacking a functional corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1. Nat Genet. 1998;19:162–166. doi: 10.1038/520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TY, Chen XQ, Du JZ, Xu NY, Wei CB, Vale WW. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor type 1 and type 2 mRNA expression in the rat anterior pituitary is modulated by intermittent hypoxia, cold and restraint. Neuroscience. 2004;128:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger SC, Dunn AJ, Muglia LJ, Dikkes P, Miczek KA, Swiergiel AH, Berridge CW, Majzoub JA. Stress-induced behaviors require the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor, but not CRH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8283–8288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitnall MH. Regulation of the hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurosecretory system. Progr Neurobiol. 1993;40:573–629. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(93)90035-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]