Abstract

Excitotoxicity, induced either by N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) or kainic acid (KA), promotes irreversible loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). Although the intracellular signaling mechanisms underlying excitotoxic cell death are still unclear, recent studies on the retina indicate that NMDA promotes RGC death by increasing phosphorylation of cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element (CRE)-binding protein (CREBP), while studies on the central nervous system indicate that KA promotes neuronal cell death by decreasing phosphorylation of CREBP, suggesting that CREBP can elicit dual responses depending on the excitotoxic-agent. Interestingly, the role of CREBP in KA-mediated death of RGCs has not been investigated. Therefore, by using an animal model of excitotoxicity, the aim of this study was to investigate whether excitotoxicity induces RGC death by decreasing Ser133-CREBP in the retina. Death of RGCs was induced in CD-1 mice by an intravitreal injection of 20 n moles of kainic acid (KA). Decrease in CREBP levels was determined by immunohistochemistry, western blot analysis, and electrophoretic mobility gel shift assays (EMSAs). Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that CREBP was constitutively expressed in the nuclei of cells both in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and in the inner nuclear layer (INL) of CD-1 mice. At 6 h after KA injection, nuclear localization of Ser133-CREBP was decreased in the GCL. At 24 h after KA injection, Ser133-CREBP was decreased further in GCL and the INL, and a decrease in Ser133-CREBP correlated with apoptotic death of RGCs and amacrine cells. Western blot analysis indicated that KA decreased Ser133-CREBP levels in retinal protein extracts. EMSA assays indicated that KA also reduced the binding of Ser133-CREBP to CRE consensus oligonucleotides. In contrast, intravitreal injection of CNQX, a non-NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist, restored the KA-induced decrease in Ser133-CREBP both in in the GCL and INL, and inhibited loss of RGCs and amacrine cells. These results, for the first time, suggest that KA promotes retinal degeneration by reducing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP in the retina.

Keywords: Retina, CREBP, excitotoxicity, apoptosis, ganglion cells, amacrine cells, and retinal degeneration

INTRODUCTION

Hyper-stimulation of glutamate receptors (excitotoxicity) in the retina and in the central nervous system leads to neuro-degeneration (Schwarcz and Coyle, 1977; Siliprandi et al., 1992). Although a number of previous studies have suggested that hyper-stimulation of both NMDA and non-NMDA-type glutamate receptors promotes irreversible death of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) (Chidlow and Osborne, 2003; Siliprandi et al., 1992), the intracellular signals that promote excitotoxicity-induced cell death are unclear. Previous studies have suggested that cyclic AMP (cAMP) regulates a number of transcriptional factors and dictates cell survival (Shaywitz and Greenberg, 1999). One of these transcription factors, cAMP-response element (CRE)-binding protein (CREBP), has been suggested to play a major role in cell survival and synaptic plasticity of neuronal cells (Lonze et al., 2002; Walton et al., 1999; Walton and Dragunow, 2000).

CREBP, a 43 kDa nuclear protein, is constitutively expressed by many neuronal cells, including RGCs (Choi et al., 2003a; Harada et al., 1995; Walton et al., 1999; Walton and Dragunow, 2000; Yoshida et al., 1995b; Zhang et al., 2005). CREBP consists of three functional domains: a transactivation region containing the site for phosphorylation (also known as the kinase domain), a DNA-binding domain consisting of basic amino acids (basic domain), and a leucine zipper domain (bZip domain). In response to extracellular stimuli, CREBP becomes phosphorylated at serine133 (Johannessen et al., 2004; Montminy et al., 1990; Montminy et al., 1986; Zhang et al., 2005), binds to CRE site either as a monomer or a homodimer, and activates a number of CRE-target genes. Although CREBP contains many phosphorylation sites, phosphorylation of Ser133 has been suggested to play a major role in cell survival. Currently, mechanisms underlying Ser133-CREBP’s phosphorylation at the nuclear level are unclear and vary based on the stimuli. Yet, previous studies have suggested have that three intermediate-signaling pathways, Calcineurin, mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK), and Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type IV (CaMKIV pathways) may play a role in Ser133-CREBP’s phosphorylation at the nuclear level (Bito et al., 1996; Impey et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2005; Sun et al., 1994; Xing et al., 1996).

Although a number of previous reports have indicated that both KA and NMDA promote the death of RGCs (Mali et al., 2005; Manabe and Lipton, 2003; Siliprandi et al., 1992; Zhang et al., 2004a), the role of Ser133-CREBP in RGC death has not been investigated extensively. To date, a few studies reported varying results with regard to Ser133-CREBP expression in the retina. For example, Yoshida et al., (Yoshida et al., 1995a) reported that both flashing light and administration of Bay K8644, a L-type Ca2+ channel activator, induced phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP in the nuclei of amacrine cells and ganglion cells. Another study by Choiet al., (Choi et al., 2003b) reported that monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1) protected retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve injury through enhanced Ser133-CREBP’s phosphorylation. Finally, by increasing intraocular pressure (IOP), a study by Kim and Park (Kim and Park, 2005) reported that the number of Ser133-CREBP-positive cells decreased with time after injury.

Recent studies on the retina have indicated that NMDA promotes RGC death by increasing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP (Isenoumi et al., 2004), while studies on the central nervous system have shown that KA promotes neuronal cell death by decreasing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP (Lee et al., 2002). These results suggest that Ser133-CREBP can elicit dual responses on cell survival depending on the excitotoxic-agent used. Interestingly, the role of Ser133-CREBP in KA-mediated survival of RGCs has not been investigated. Therefore, by using an animal model of KA-mediated excitotoxicity, the aim of this study was to investigate whether KA induces RGC death by regulating phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP in the retina.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Initiation of excitotoxicity

All experiments on animals were performed under general anesthesia according to institutional protocol guidelines and the guidelines set forth by the association for research in vision and ophthalmology (ARVO). Normal adult CD-1 mice (6–8 weeks old; Charles River Breeding Labs, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 1.25% avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol in tert-amyl alcohol; 17 uL/g body weight). Throughout this study, unilateral intravitreal injections were performed in a final volume of 2 uL. For control experiments, eyes (n=6; three independent experiments) were injected with 2 uL of 0.1M phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Treatment group eyes (n=6; three independent experiments) were injected with 2 uL of 10 mM (corresponding to a final concentration of 20 n moles) kainic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), prepared in PBS. In a separate set of experiments, eyes (n=6; three independent experiments) were injected with 1 uL of 20 mM KA plus 1 uL of 400 mM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; a non-NMDA receptor blocker; corresponding to a final concentration of 200 n moles; Tocris, Ellisville, MO).

Extraction of cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins

At 6 and 24 h after intravitreal injection of KA, three mice were anesthetized with an overdose of avertin and their eyes were enucleated (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments). After removing the cornea and lens, retinas were carefully peeled off using forceps and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4). Since Ser133-CREBP is a nuclear protein, proteins were separated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions according to our previously published methods (Chintala et al., 1998). Briefly, 6 retinas were placed in Eppendorff tubes, washed in cold PBS, and re-suspended in a buffer containing 400–600 uL of M KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2.0 mg/mL leupeptin, 2.0 mg/mL aprotinin, 0.5 mg/mL benzamidine. The tubes were allowed to stay on ice for 20 min followed by the addition of 12.5 uL of 10% Nonidet P-40. The tubes were vortexed vigorously for 10s, and the homogenates centrifuged for 30s. The supernatant containing the cytoplasmic proteins was saved for further experiments. The nuclear pellets were re-suspended in 50 uL of ice-cold nuclear extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2.0 mg/ml leupeptin, 2.0 mg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 mg/ml benzamidine) and incubated on ice for 30 min with intermittent vortexing. Samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant containing nuclear proteins was stored at −70°C until further use. Protein concentration in supernatants was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of protein (75 μg) from PBS or KA-treated retinas (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments) were mixed with gel-loading buffer and separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred to PVDF (Polyvinylidene Fluoride) membranes and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in blocking buffer (10% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 [TBS-T]). Membranes were then probed with antibodies against CREBP (phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated, 1:2000 dilution in TBS-T, Santacurz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with TBS-T, membranes were incubated with horseradishperoxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature (1:2500 dilution, Santacruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Proteins on the membranes were detected by using an ECL chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and by exposing the membranes to X-ray film. Finally, protein bands were scanned with a densitometer, normalized to un-phosphorylated CREBP, and representative results from two independent experiments were shown. Data from 6 different eyes (three independent experiments) were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a post hoc-Tukey’s test by using GB-Stat Software (Dynamic Microsystems, MD) and expressed as mean +/− SEM.

DNA-protein binding assays

DNA-protein interactions were determined by EMSAs according to the procedures described previously (Chintala et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2003). Briefly, 4 ug of nuclear extract was incubated with 16 fmol of 32P-labeled CRE oligonucleotides (5′-AGA GAT TGC CTG ACG TCA GAG AGC TAG-3′) for 15 min at 37° C. Two-three ug of poly (dI-dC) was included in the binding buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl) to inhibit non-specific binding. The DNA-protein complexes were then separated from free oligonucleotides on 7.5% native polyacrylamide gels using a buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 200 mM glycine, pH 8.5, and 1 mM EDTA. The gels were dried, and DNA-protein bands were visualized by capturing the bands on a x-ray film.

Immunohistochemistry

Radial sections

At 6 and 24 h after injection of either PBS or KA eyes (n=6; three independent experiments) were enucleated, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. Eye cups were placed in OCT compound (Fisher Scientific, Chicago, IL), and ten micron-thick retinal cross sections were prepared according to our previously published methods (Zhang et al., 2004a, b). Retinal cross sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (1 h at room temperature) and incubated overnight at 4° C with primary antibodies against Ser133-CREBP (1:100 dilution in PBS; Santacruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). In addition, retinal cross sections were incubated with antibodies against calretinin (1:100 dilution in PBS; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). After overnight incubation, sections were washed with PBS (pH 7.2) and incubated with AlexaFluor568-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution, Molecular Probes, Eugene, CA). For results presented in Figure 1, sections were also counterstained with 1 mg/mL of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture, but secondary antibodies were added. Sections were observed under a Nikon fluorescence microscope, and digitized images were obtained using a SpotR digital camera. Images were compiled by using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe System Incorporated, San Jose, CA). Number of Ser133-CREBP-positive cells was counted and results from 6 different eyes (three independent experiments). Statistical significance was analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a post hoc-Tukey’s test by using GB-Stat Software (Dynamic Microsystems, MD), and expressed as mean +/− SEM.

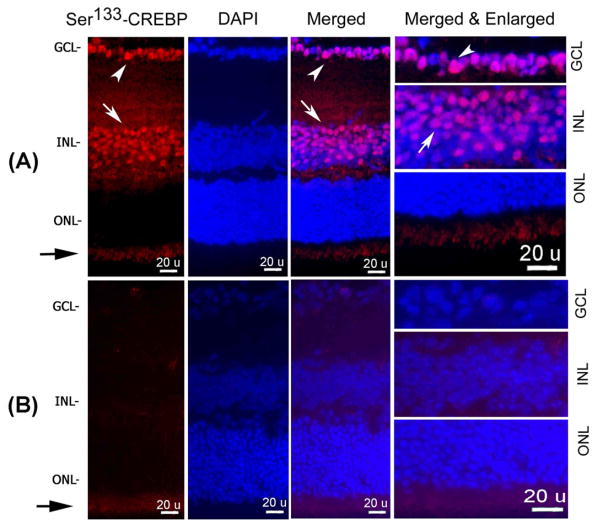

Figure 1. Ser133-CREBP expression in the retina.

Retinal cross sections prepared from normal adult CD-1 mice (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments) were incubated with primary antibodies against Ser133-CREBP and AlexaFluor-568 conjugated secondary antibodies (Figure 1A). Retinal cross sections were also counter-stained with DAPI and representative images from three independent experiments were shown. For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture (Figure 1B). Results presented in Figure 1A indicate (first and third panels, arrow heads) that Ser133-CREBP-positive staining constitutively both in the GCL and INL. Merged and enlarged images of Ser133-CREBP and DAPI showed nuclear localization of Ser133-CREBP in GCL (Figure 1A, right most panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 1A, right most panel, arrow). A slight positive immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1A and B, black arrows) in the inner plexiform layer (IPL) represents auto-fluorescence. Negative controls showed a slight positive immunofluorescence (Figure 1B) in the IPL indicating auto-fluorescence.

Flat-mounted Retinas

At 6 and 24 h after injection of either PBS or KA, eyes (n=6; three independent experiments) were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. Corneas and lenses were removed, and the remaining eyecups were incubated in 4% paraformaldehyde for another 30 min. Retinas were carefully peeled off, washed three times with PBS, and RGCs remaining in the retinas were identified according to methods described by Nadal-Nicolas et al.(Nadal-Nicolas et al., 2009) Briefly, whole retinas were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton-X100 (in PBS) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Retinas were washed three times with PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C in a buffer containing polyclonal antibodies against Brn3a (1: 100 dilution in blocking buffer [(2% bovine serum albumin, 2% Triton-X100, and PBS)]). After overnight incubation, retinas were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature in a buffer containing secondary antibodies conjugated to AlexaFlour-568 (1:200 dilution in blocking buffer). Retinas were washed three times with PBS and mounted onto slides, vitreous side facing upwards. For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture, but secondary antibodies were added. Brn3a-positive RGCs in whole mounted retinas were assessed by observing flat mounted retinas under a Nikon fluorescence microscope, and digitized images were obtained using a SpotR digital camera. Images were compiled by using Photoshop software (Adobe System Incorporated, San Jose, CA). The total number of Brn3a-positive cells in the retinas, located approximately at the same distance from the optic disk (7200 sq. microns, 40x magnification) was quantitated by using Scion Image analysis software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD). For quantitative analysis, Brn3a-positive cells were counted in four to six microscope fields of identical size located at approximately 1–2 mm from the optic disc. Data from 6 different eyes (three independent experiments) were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a post hoc-Tukey’s test by using GB-Stat Software (Dynamic Microsystems, MD) and expressed as means +/− SEM.

TUNEL assays

Apoptotic cell death in the retina was determined by a TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay as previously described (Zhang et al., 2004a). Total numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were quantified by counting cells in a 40x field at a distance of 1–2 mm from the optic disc. No attempts were made to differentiate between ganglion cells and displaced amacrine cells during counting. Data from 6 different eyes (three independent experiments) were analyzed by ANOVA, followed by a post hoc-Tukey’s test by using GB-Stat Software (Dynamic Microsystems, MD) and expressed as mean +/− SEM.

RESULTS

Ser133-CREBP is expressed constitutively in the retina

To determine the expression of Ser133-CREBP in the retina, retinal cross sections prepared from normal adult CD-1 mice were subjected to immunohistochemistry by using antibodies against Ser133-CREBP (Figure 1A). Retinal cross sections were also counterstained with DAPI. Results presented in Figure 1A (first and third panels, arrow heads) indicate that Ser133-CREBP-positive staining was present both in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) and inner nuclear layer (INL) constitutively. Merged and enlarged images of Ser133-CREBP and DAPI showed nuclear localization of Ser133-CREBP in the GCL (Figure 1A, right most panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 1A, right most panel, arrow). Slightly positive immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1A and B, black arrows) in the inner plexiform layer (IPL) represents auto-fluorescence. Negative controls in which primary antibody was omitted from the reaction mixture showed slightly positive immunofluorescence (Figure 1B) in the IPL indicating auto-fluorescence.

KA decreases Ser133-CREBP levels in the retina

To determine the effect of KA on Ser133-CREBP expression, retinal cross sections prepared from CD-1 mice at 6 and 24h after intravitreal injections were immunostained by using antibodies against Ser133-CREBP. We have used CD-1 mice because KA-induces reproducible apoptotic death of RGCs as early as 6 h and significant apoptotic death of RGCs and amacrine cells at 24 h in these mice (Zhang et al., 2004a). Results presented in Figure 2A indicate that at 6h after KA injection, Ser133-CREBP immunostaining was decreased in the GCL by ~34% (Figure 2A, third panel, arrow head) and at 24 h in both the GCL (Figure 2A, fourth panel, arrow head) and INL by ~67% (Figure 2A, fourth panel, arrow). Quantitative analysis (Figure 2B) indicated that the density of Ser133-CREBP-positive cells in the GCL and INL was reduced significantly at 6h and 24 h, when compared to PBS-treated retinas (*, **p<0.05).

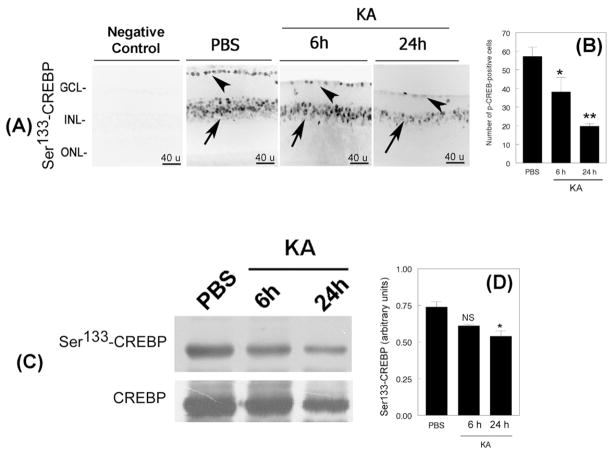

Figure 2. KA decreases Ser133-CREBP levels in the retina.

Retinal cross sections prepared after intravitreal injection of PBS or KA (n=6 eyes; three independent experiments) were immunostained with antibodies against Ser133-CREBP (Figure 2A), and the number of Ser133-CREBP-positive cells quantified by using Scion analysis (Figure 2B). For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture. Immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 2A) indicated that Ser133-CREBP was expressed constitutively in both the GCL (Figure 2A, second panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 2A, second panel, arrow) in PBS-treated retinas. Compared to PBS-treated retinas, Ser133-CREBP expression was decreased in the GCL (Figure 2A, third and fourth panels, arrow heads) and in INL (Figure 2, third and fourth panels, arrow) at 6 and 24 h after KA-treatment.

After 6 and 24 h of KA-treatment, nuclear proteins were extracted, and aliquots containing an equal amount of protein (75 ug) were subjected to western blot analysis (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments). Results presented in Figure 2C indicate that Ser133-CREBP is expressed in PBS-treated retinas constitutively. In contrast, Ser133-CREBP levels were gradually decreased in KA-treated retinas both at 6and 24 h. While un-phosphorylatedSer133-CREBP levels were decreased slightly at 24 h after KA-treatment, un-phosphorylated Ser133-CREBP levels were largely unchanged in PBS-treated and KA-treated retinas at 6h. When compared to protein bands in PBS or KA-treated retinas, densitometic analysis (Figure 2D) indicated that Ser133-CREBP levels decreased significantly at 24 h, but not at 6 h (*, p<0.05; NS, not significant)

KA-decreases phosphorylated Ser133-CREBP levels in the retina

To determine whether the KA-induced decrease observed by immunohistochemical analysis correlates with Ser133-CREBP levels, nuclear proteins were extracted at 6 and 24 h after KA-treatment. Aliquots containing an equal amount (75 ug) of nuclear proteins from PBS and KA-treated retinas were subjected to western blot analysis by using antibodies against phosphorylated and un-phosphorylated Ser133-CREBP. Western blot analysis (Figure 2C) showed constitutive expression of Ser133-CREBP in retinal proteins extracted from PBS-injected eyes. In contrast, Ser133-CREBP levels were decreased (Figure 2C) slightly at 6h and considerably at 24 h. After normalizing Ser133-CREBP protein bands to un-phosphorylated protein bands, densitometric analysis (Figure 2D) indicated that Ser133-CREBP levels were reduced significantly at 24 h (*p<0.05), but not at 6 h after KA-treatment (NS, not significant).

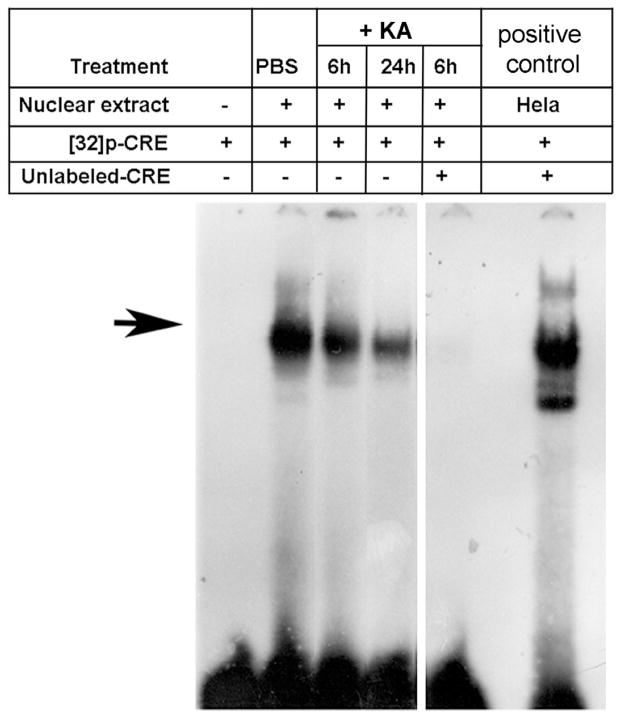

KA-decreases Ser133-CREBP-binding activity of CRE in the retina

Since KA decreased Ser133-CREBP levels as observed by immunofluorescence (Figure 2A) and western blot analysis (Figure 2C), EMSA assays were performed to determine whether decreased levels of Ser133-CREBP are reflected by a decreased binding of Ser133-CREBP to CRE elements. Nuclear proteins were extracted from PBS and KA-treated retinas, and aliquots containing an equal amount of nuclear protein (4 ug) were incubated with 16 fmol of p32-labeled CRE–oligonucleotides. Three hours after incubation, DNA-protein complexes were subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Results presented in Figure 3 indicated constitutive DNA-binding activity of Ser133-CREBP in PBS-treated retinas. In contrast, DNA-binding activity of Ser133-CREBP was decreased gradually in KA-treated retinas both at 6 and 24 h. When nuclear proteins extracted from KA-injected eyes were incubated with labeled CRE and an excess of unlabeled CRE, Ser133-CREBP binding to CRE elements was inhibited. Hela cell extracts used as positive controls also showed DNA-binding activity of Ser133-CREBP.

Figure 3. KA decreases Ser133-CREBP-binding activity to CRE.

After 6 and 24 h of KA-treatment (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments), nuclear proteins were extracted, and aliquots containing an equal amount of nuclear protein (4 ug) were incubated with 16 fmol of p32-lableled CRE oligonucleotides, and electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed. Hela cell nuclear extracts incubated with p32-labeled CRE served as a positive control. An excess of unlabeled CRE served as a negative control (competition experiments). EMSA results (Figure 3, arrow) indicated that KA progressively decreases Ser133-CREBP binding to CRE at 6 and 24 h.

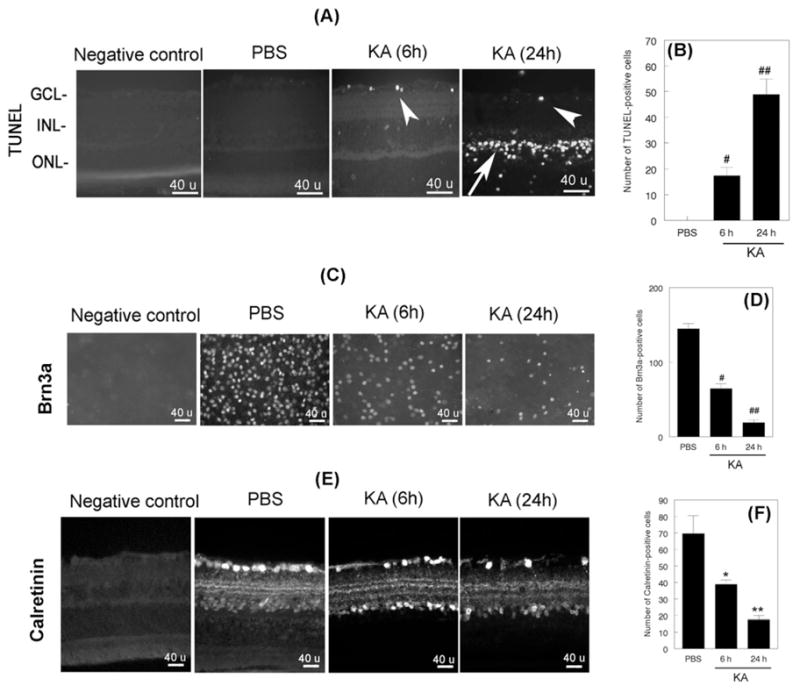

Decreased levels of Ser133-CREBP associates with apoptotic death of RGCs and amacrine cells

To determine the effect of reduced Ser133-CREBP levels (shown in Figure 2A and C) on apoptotic death of retinal neurons, retinal cross sections prepared from PBS or KA-treated animals were subjected to TUNEL assays. Results presented in Figure 4A indicated that reduced levels of Ser133-CREBP were associated with a ~17% increase in TUNEL-positive cells in the GCL at 6 h (Figure 4A, third panel, arrow head), and a ~48% increase in the GCL (Figure 4A, fourth panel, arrow head) and INL by 24 h (Figure 4A, fourth panel, arrow). No TUNEL-positive cells were observed in PBS-treated retinas (Figure 4A, second panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 4B) indicated a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells in the GCL at 6h and in INL at 24 h (#, ##, p<0.05, when compared KA and PBS-treated retinas).

Figure 4. Decreased Ser133-CREBP levels associate with apoptotic death of RGCs and amacrine cells.

Retinal cross sections prepared after intravitreal injection of PBS or KA (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments) were subjected to TUNEL assays to determine apoptotic cell death (Figure 4A) and immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against calretinin (Figure 4E). RGC loss in flat-mounted retinas was determined by immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against Brn3a (Figure 4C). For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture. Compared to PBS-treated retinas, TUNEL-positive cells were increased initially in the GCL (Figure 4A, third panel, arrowhead) and subsequently in both the GCL (Figure 4A, fourth panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 4A, fourth panel, arrow). Quantitative analysis (B) indicated a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells at 6 h in the GCL and (#, p<0.05) and in the INL at 24 h after KA-treatment (##, p<0.05). No TUNEL-positive cells were observed in PBS-treated retinas. Immunofluorescence staining for Brn3a indicated that KA-induced a gradual loss of RGCs at 6 (Figure 4C, third panel) and 24 h after treatment (Figure 4C, fourth panel), when compared to PBS-treated retinas (Figure 4C, second panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 4D) indicated that KA induced significant loss of RGCs at both 6 and 24 h after treatment (#, ##, p<0.05). Immunofluorescence staining for amacrine cells (E) indicated that KA decreased amacrine cells at 6(Figure 4E, third panel) and 24 h (Figure 4E, fourth panel), when compared to PBS-PBS-treated retinas (Figure 4E, second panel). Quantitative analysis (F) indicated that KA induced a significant loss of amacrine cells at both 6 and 24 h after treatment (*,**, p<0.05).

Since apoptotic cells were observed in the GCL and INL, additional experiments were performed to identify which cells underwent apoptosis. First, loss of RGCs was assessed by immunostaining of flat-mounted retinas with antibodies against Brn3a. Results presented in Figure 4C indicate that the density of Brn3a-positive RGCs was reduced by ~56% at 6 h (Figure 4C, third panel) and by ~87% at 24 h (Figure 4C, fourth panel) after KA injection, when compared to PBS injected eyes (Figure 4C, second panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 4D) indicated that the number of Brn3a-positive RGCs was significantly decreased both at 6 h and 24 h after KA injection, when compared to PBS-injected eyes (#, ##, p<0.05).

Second, loss of amacrine cells was assessed by immunostaining of retinal cross sections with antibodies against calretinin. Results presented in Figure 4E indicate that the number of calretinin-positive amacrine cells was decreased by ~45% at 6 h (Figure 4E, second panel) and by ~76% at 24 h after KA injection (Figure 4C, fourth panel), when compared to PBS-treated retinas (Figure 4C, second panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 4F) indicated that the number Calretinin-positive cells was reduced significantly at both 6 and 24 h, when compared to PBS-treated retinas (*, **, p<0.05).

KA antagonist restores Ser133-CREBP levels and attenuates KA-induced death of RGCs and amacrine cells

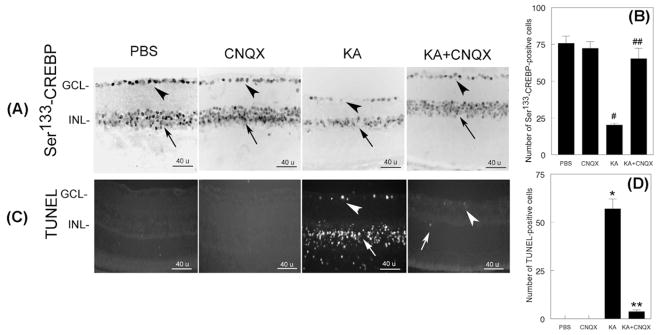

To investigate whether CNQX, an antagonist of non-NMDA type glutamate receptors, restores Ser133-CREBP in the retina, 24 h after injecting PBS, KA, or KA+CNQX, retinal cross sections were prepared and subjected to immunofluorescence analysis by using antibodies againstSer133-CREBP. Results presented in Figure 5 indicate that Ser133-CREBP is expressed constitutively in the GCL and INL of PBS (Figure 5A, first panel, arrow head) or CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 5A, second panel, arrow head). When compared to PBS or CNQX-treated retinas, Ser133-CREBP immunostaining was reduced in GCL (Figure 5A, third panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5A, third panel, arrow) by ~74% at 24 h in KA-treated retinas. In contrast, Ser133-CREBP-positive immunostaining was restored in the GCL (Figure 5A, fourth panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5A, fourth panel, arrow) to almost to normal levels in KA and CNQX-treated retinas. Quantitative analysis (Figure 5B) indicated that Ser133-CREBP-positive staining was reduced significantly in KA-treated retinas when compared to PBS-treated retinas (#, p<0.05). When the number of Ser133-CREBP-positive cells was compared between KA and KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 5B), Ser133-CREBP-positive cells were increased in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (##, p<0.05).

Figure 5. CNQX, a KA antagonist, restores Ser133-CREBP expression and inhibits apoptotic cell death of RGCs and amacrine cells.

CD-1 mice were treated with PBS, CNQX, KA or KA+CNQX for 24 h (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments), and at the end of 24 h, expression of CREBP was determined by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5A) and apoptotic cell death was determined by TUNEL assays (Figure 5C). For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture. Compared to PBS-treated (Figure 5A, first panel, arrow head and arrow) or CNQX retinas (Figure 5A, second panel, arrow head and arrow), the number of Ser133-CREBP-positive cells was decreased both in the GCL (Figure 5A, third panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5A, third panel, arrow) in KA-treated retinas (Figure 5B, #, p<0.05; PBS vs KA). Compared to PBS (Figure 5C, first panel) or CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 5C, second panel), TUNEL-positive cells were increased in the GCL (Figure 5C, third panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5C, third panel, arrow) in KA-treated retinas. A few TUNEL-positive cells were observed in the GCL (Figure 5C, fourth panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5C, fourth panel, arrow) in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas. Quantitative analysis (Figure 5D) indicated that TUNEL-positive cells were significantly increased in KA-treated retinas, but not in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (*,**, p<0.05, when compared to PBS or CNQX-treated retinas).

To determine whether restoration of Ser133-CREBP levels inhibits apoptotic death of retinal neurons, retinal cross sections prepared at 24 h after PBS, CNQX, KA, and KA plus CNQX were subjected to TUNEL assays. Results presented in Figure 5C indicate that KA increases apoptotic death of cells by ~57% in both the GCL (Figure 5C, third panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5C, third panel, arrow). While only ~3% of TUNEL-positive cells were found in GCL (Figure 5C, fourth panel, arrow head) and INL (Figure 5C, fourth panel, arrow) in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas, no TUNEL-positive cells were found in PBS or CNQX-treated retinas. Quantitative analysis of TUNEL-positive cells indicated that KA plus CNQX-treatment significantly reduced KA-induced apoptotic cell death (*, **, p<0.05).

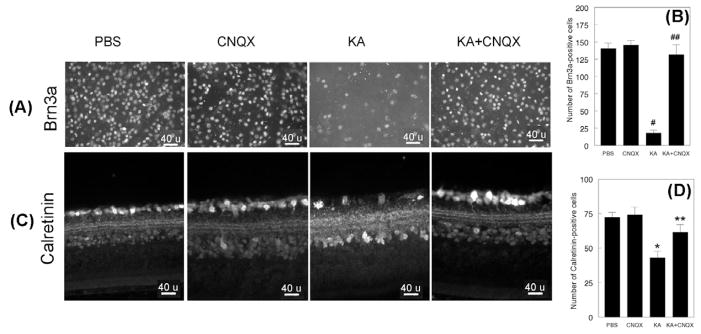

To determine whether restoration of Ser 133-CREBP levels inhibits loss of RGCs, retinal flat mounts prepared at 24 h after PBS, CNQX, KA, or KA plus CNQX-treatment were immunostained with antibodies against Brn3a. Compared to PBS and CNQX-treated retinas, the density of Brn3a-postive RGCs (Figure 6A) was decreased by ~88% in KA-treated retinas (Figure 6A, third panel), but not in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 6A, fourth panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 6B) indicated that the Brn3a-positive RGCs were reduced significantly in KA-treated retinas (#, p<0.05), but not in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (##, p<0.05).

Figure 6. CNQX inhibits loss of RGCs and amacrine cells.

CD-1 mice were treated with PBS, CNQX, KA or KA+CNQX for 24 h (n=6 retinas; three independent experiments). At the end of 24 h, the remaining RGCs were assessed by immunostaining of retinal flat mounts with antibodies against Brn3a (Figure 6A) and the remaining amacrine cells in retinal cross sections determined by using antibodies against calretinin (Figure 6C). For negative controls, primary antibodies were omitted from the incubation mixture. When compared to PBS (Figure 6A, first panel) or CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 6A, second panel), the number of Brn3a-postive cells was reduced considerably in KA-treated retinas (Figure 6A, third panel), but not in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 6A, fourth panel). Quantitative analysis indicated that Brn3a-positive RGCs were reduced significantly in KA-treated retinas (Figure 6B), but not in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (*,**, p<0.05). Calretinin immunostaining indicated that amacrine cells were reduced in KA-treated retinas (Figure 6C, third panel), but not in PBS (Figure 6C, first panel), CNQX (Figure 6C, second panel), or KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 6C, fourth panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 6D) indicated that calretinin-positive amacrine cells were reduced significantly in KA-treated retinas, but not in PBS, CNQX, or KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (*,*, p<0.05)

Finally, to determine whether KA and CNQX-treatment attenuates KA-induced loss of amacrine cells, retinal cross sections prepared at 24 h after PBS, CNQX, KA, or KA plus CNQX-treatment were immunostained with antibodies against calretinin. Compared to PBS and CNQX-treated retinas, the number of calretinin-positive cells was reduced by ~48% in KA-treated retinas (Figure 6C, third panel) and by only ~16% in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 6C, fourth panel), when compared to PBS (Figure 6C, first panel) or CNQX-treated retinas (Figure 6C, second panel). Quantitative analysis (Figure 6D) indicated that calretinin-positive cells were significantly decreased in the GCL and INL in KA-treated retinas, but not KA plus CNQX-treated retinas (*, **, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

A number of previous studies by our laboratory and others have reported that excitotoxicity induced by hyper-stimulating both NMDA or non-NMDA-type glutamate receptors promote death of RGCs and amacrine cells (Mali et al., 2005; Morgan and Ingham, 1981; Schwarcz and Coyle, 1977; Sucher et al., 1991; Zhang et al., 2004a). Although the intracellular mechanisms underlying excitotoxicity-induced neuronal cell death are still unclear, previous studies have reported that the phosphorylation status of Ser133-CREBP plays an important role in dictating survival of neuronal cells (Montminy et al., 1990; Shaywitz and Greenberg, 1999; Walton et al., 1999; Walton and Dragunow, 2000). For example, in a rat model of excitotoxicity, Isenoumi et al.(Isenoumi et al., 2004) reported that 12 and 24 h after intravitreal injection of NMDA, an increased phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP promoted the death of RGCs. On the other hand, studies on the central nervous system have shown that KA-mediated excitotoxicity promotes neuronal cell death by decreasing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP (Lee et al., 2002). Until now, it was unclear whether KA promotes RGC death by regulating phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP in the retina. In this study, we have shown that kainic acid, which hyper-stimulates non-NMDA-type receptors, promotes the death of RGCs and amacrine cells by decreasing the phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP.

We have found that Ser133-CREBP is expressed constitutively in both the GCL and INL of retinas of normal adult CD-1 mice. When CD-1 mice were treated with PBS alone, Ser133-CREBP levels were unaltered. In contrast, when CD-1 mice were treated with KA, Ser133-CREBP levels were decreased initially in the GCL, but not in the INL. However, at 24 h, Ser133-CREBP was decreased further in the INL. Western blot analysis indicated that loss of Ser133-CREBP immunostaining in the retina correlated with reduced levels of Ser133-CREBP in retinal protein extracts. DNA-protein binding assays indicated that reduced levels of Ser133-CREBP in retinal protein extracts correlated with reduced binding of Ser133-CREBP to CRE oligonucleotides. Immunofluorescence analysis indicated that reduced levels of CREBP correlated with a significant loss of RGCs and amacrine cells in KA-treated retinas. Interestingly, a decrease in Ser133-CREBP levels was associated with apoptotic death of cells initially in the GCL and subsequently in INL. Although it is possible that injury initiated in the RGC layer may lead to secondary degeneration of amacrine cells, results presented in this study suggest that KA promotes amacrine cell loss by decreasing Ser133CREBP levels. Finally, when CD-1 mice were treated with KA plus CNQX (a non-NMDA-receptor antagonist), Ser133-CREBP levels were restored to almost normal levels in both the GCL and INL. In addition, restored Ser133-CREBP levels correlated with significant reduction in apoptotic cell death in the GCL and INL, Furthermore, restored levels of Ser133-CREBP in KA plus CNQX-treated retinas correlated with a significant reduction in the loss of RGCs and amacrine cells. These results suggest that KA decreases phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP in the retina and promotes retinal degeneration.

Although both NMDA and KA have been shown to promote death of RGCs, it is interesting to note that these two glutamate receptor agonists regulate cell death by either decreasing or increasing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP (Johannessen et al., 2004). It is also interesting to note that increased phosphorylation seems to be a protective response in NMDA-mediated excitotoxicity, while decreased phosphorylation seem to be a detrimental response in KA-induced excitotoxicity (Alberts et al., 1994; Mabuchi et al., 2001; Ramirez and Lamas, 2009). How these two agonists differentially phosphorylate CREBP is unclear at this time. There are several interesting possibilities that have been suggested and supported by previous studies:1) Ser133-CREBP can induce the expression of c-fos and c-jun transcription factors, which are known to induce a number of genes that control cell survival (Dragunow et al., 1994; Zhang et al., 2005). 2) Ser133-CREBP can differentially regulate the pro-apoptotic gene, Bax, and the anti-apoptotic gene, BcL-2 (Hansen et al., 2004; Lonze et al., 2002; Mabuchi et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 1996). 3) Ser133-CREBP can be differentially phosphorylated by various kinases including protein kinase A (PKA) and Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CAMKs)(Bito et al., 1996; Kasahara et al., 2000; Shaywitz and Greenberg, 1999; Soderling, 2000). 4) CAMKs that regulate phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP can be differentially regulated by NMDA and KA (Shaywitz and Greenberg, 1999; Suh et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2001). 5) NMDA and KA can differentially regulate phosphorylation of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs), which, in turn, can regulate phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP (Impey et al., 1998; Nateri et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2001). 6) NMDA and KA may differentially regulate expression of Ser133-CREBP kinases, such as serine–threonine protein 2A (PP2A), that govern the phosphorylation status of Ser133-CREBP (Alberts et al., 1994; Wadzinski et al., 1993). Further studies are needed to determine which of these potential mechanisms may be involved with differential regulation of Ser133-CREBP in mouse RGCs.

In summary, we have shown, for the first time, that unlike NMDA that promotes the death of RGCs and amacrine cells by increasing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP, kainic acid promotes the death of RGCs and amacrine cells by reducing phosphorylation of Ser133-CREBP. These results suggest that strategies to restore Ser133-CREBP’s phosphorylation in the retina may be a potential therapeutic approach to prevent excitotoxic retinal degeneration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by a National Eye Institutes Project grant EY017853-01A2 (to SKC) and a Vision Research Infrastructure Development Grant EY014803. The authors thank Mei Cheng and Omar Yaldo for their technical assistance, and Frank Giblin, Ph.D. for critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used

- GCL

ganglion cell layer

- INL

inner nuclear layer

- KA

Kainic acid

- TUNEL

TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

- CRE

cAMP-response element

- CREBP

cAMP-response element-binding protein

- EMSA

electrophoretic mobility-shift assay

- OCT compound

optimal cutting temperature compound

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alberts AS, Arias J, Hagiwara M, Montminy MR, Feramisco JR. Recombinant cyclic AMP response element binding protein (CREB) phosphorylated on Ser-133 is transcriptionally active upon its introduction into fibroblast nuclei. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7623–7630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bito H, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. CREB phosphorylation and dephosphorylation: a Ca(2+)- and stimulus duration-dependent switch for hippocampal gene expression. Cell. 1996;87:1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidlow G, Osborne NN. Rat retinal ganglion cell loss caused by kainate, NMDA and ischemia correlates with a reduction in mRNA and protein of Thy-1 and neurofilament light. Brain Res. 2003;963:298–306. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintala SK, Sawaya R, Aggarwal BB, Majumder S, Giri DK, Kyritsis AP, Gokaslan ZL, Rao JS. Induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 requires a polymerized actin cytoskeleton in human malignant glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13545–13551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Kim JA, Joo CK. Activation of MAPK and CREB by GM1 induces survival of RGCs in the retina with axotomized nerve. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003a;44:1747–1752. doi: 10.1167/iovs.01-0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JS, Kim JA, Joo CK. Activation of MAPK and CREB by GM1 induces survival of RGCs in the retina with axotomized nerve. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003b;44:1747–1752. doi: 10.1167/iovs.01-0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Beilharz E, Sirimanne E, Lawlor P, Williams C, Bravo R, Gluckman P. Immediate-early gene protein expression in neurons undergoing delayed death, but not necrosis, following hypoxic-ischaemic injury to the young rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;25:19–33. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HH, Briem T, Dzietko M, Sifringer M, Voss A, Rzeski W, Zdzisinska B, Thor F, Heumann R, Stepulak A, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Mechanisms leading to disseminated apoptosis following NMDA receptor blockade in the developing rat brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16:440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Imaki J, Hagiwara M, Ohki K, Takamura M, Ohashi T, Matsuda H, Yoshida K. Phosphorylation of CREB in rat retinal cells after focal retinal injury. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61:769–772. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impey S, Smith DM, Obrietan K, Donahue R, Wade C, Storm DR. Stimulation of cAMP response element (CRE)-mediated transcription during contextual learning. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:595–601. doi: 10.1038/2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenoumi K, Kumai T, Kitaoka Y, Motoki M, Kuribayashi K, Munemasa Y, Kogo J, Kobayashi S, Ueno S. N-methyl-D-aspartate induces phosphorylation of cAMP response element (CRE)-binding protein and increases DNA-binding activity of CRE in rat retina. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:108–114. doi: 10.1254/jphs.95.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen M, Delghandi MP, Moens U. What turns CREB on? Cell Signal. 2004;16:1211–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara J, Fukunaga K, Miyamoto E. Activation of CA(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:594–600. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000301)59:5<594::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Park CK. Retinal ganglion cell death is delayed by activation of retinal intrinsic cell survival program. Brain Res. 2005;1057:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Butcher GQ, Hoyt KR, Impey S, Obrietan K. Activity-dependent neuroprotection and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB): kinase coupling, stimulus intensity, and temporal regulation of CREB phosphorylation at serine 133. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1137–1148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4288-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Choi SS, Lee HK, Han KJ, Han EJ, Suh HW. Effects of MK-801 and CNQX on various neurotoxic responses induced by kainic acid in mice. Mol Cells. 2002;14:339–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Riccio A, Cohen S, Ginty DD. Apoptosis, axonal growth defects, and degeneration of peripheral neurons in mice lacking CREB. Neuron. 2002;34:371–385. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00686-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabuchi T, Kitagawa K, Kuwabara K, Takasawa K, Ohtsuki T, Xia Z, Storm D, Yanagihara T, Hori M, Matsumoto M. Phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein in hippocampal neurons as a protective response after exposure to glutamate in vitro and ischemia in vivo. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9204–9213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09204.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali RS, Cheng M, Chintala SK. Plasminogen activators promote excitotoxicity-induced retinal damage. Faseb J. 2005;19:1280–1289. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3403com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe S, Lipton SA. Divergent NMDA signals leading to proapoptotic and antiapoptotic pathways in the rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:385–392. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy MR, Gonzalez GA, Yamamoto KK. Regulation of cAMP-inducible genes by CREB. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:184–188. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90045-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy MR, Sevarino KA, Wagner JA, Mandel G, Goodman RH. Identification of a cyclic-AMP-responsive element within the rat somatostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:6682–6686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan IG, Ingham CA. Kainic acid affects both plexiform layers of chicken retina. Neurosci Lett. 1981;21:275–280. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Nicolas FM, Jimenez-Lopez M, Sobrado-Calvo P, Nieto-Lopez L, Canovas-Martinez I, Salinas-Navarro M, Vidal-Sanz M, Agudo M. Brn3a as a marker of retinal ganglion cells: qualitative and quantitative time course studies in naive and optic nerve-injured retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3860–3868. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nateri AS, Raivich G, Gebhardt C, Da Costa C, Naumann H, Vreugdenhil M, Makwana M, Brandner S, Adams RH, Jefferys JG, Kann O, Behrens A. ERK activation causes epilepsy by stimulating NMDA receptor activity. EMBO J. 2007;26:4891–4901. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M, Lamas M. NMDA receptor mediates proliferation and CREB phosphorylation in postnatal Muller glia-derived retinal progenitors. Mol Vis. 2009;15:713–721. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz R, Coyle JT. Kainic acid: neurotoxic effects after intraocular injection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siliprandi R, Canella R, Carmignoto G, Schiavo N, Zanellato A, Zanoni R, Vantini G. N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced neurotoxicity in the adult rat retina. Vis Neurosci. 1992;8:567–573. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800005666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderling TR. CaM-kinases: modulators of synaptic plasticity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:375–380. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucher NJ, Aizenman E, Lipton SA. N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists prevent kainate neurotoxicity in rat retinal ganglion cells in vitro. J Neurosci. 1991;11:966–971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00966.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh HW, Lee HK, Seo YJ, Kwon MS, Shim EJ, Lee JY, Choi SS, Lee JH. Kainic acid (KA)-induced Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMK II) expression in the neurons, astrocytes and microglia of the mouse hippocampal CA3 region, and the phosphorylated CaMK II only in the hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2005;381:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Enslen H, Myung PS, Maurer RA. Differential activation of CREB by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases type II and type IV involves phosphorylation of a site that negatively regulates activity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2527–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadzinski BE, Wheat WH, Jaspers S, Peruski LF, Jr, Lickteig RL, Johnson GL, Klemm DJ. Nuclear protein phosphatase 2A dephosphorylates protein kinase A-phosphorylated CREB and regulates CREB transcriptional stimulation. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2822–2834. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, Woodgate AM, Muravlev A, Xu R, During MJ, Dragunow M. CREB phosphorylation promotes nerve cell survival. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1836–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MR, Dragunow I. Is CREB a key to neuronal survival? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Fibuch EE, Mao L. Regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Chintala SK, Fini ME, Schuman JS. Ultrasound activates the TM ELAM-1/IL-1/NF-kappaB response: a potential mechanism for intraocular pressure reduction after phacoemulsification. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1977–1981. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BE, Mochon E, Boxer LM. Induction of bcl-2 expression by phosphorylated CREB proteins during B-cell activation and rescue from apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5546–5556. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GY, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW. Activity-dependent CREB phosphorylation: convergence of a fast, sensitive calmodulin kinase pathway and a slow, less sensitive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2808–2813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051634198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Ginty DD, Greenberg ME. Coupling of the RAS-MAPK pathway to gene activation by RSK2, a growth factor-regulated CREB kinase. Science. 1996;273:959–963. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Imaki J, Matsuda H, Hagiwara M. Light-induced CREB phosphorylation and gene expression in rat retinal cells. J Neurochem. 1995a;65:1499–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Imaki J, Matsuda H, Hagiwara M. Light-induced CREB phosphorylation and gene expression in rat retinal cells. J Neurochem. 1995b;65:1499–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65041499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cheng M, Chintala SK. Kainic acid-mediated upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 promotes retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004a;45:2374–2383. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Cheng M, Chintala SK. Optic nerve ligation leads to astrocyte-associated matrix metalloproteinase-9 induction in the mouse retina. Neurosci Lett. 2004b;356:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Odom DT, Koo SH, Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Best J, Chen H, Jenner R, Herbolsheimer E, Jacobsen E, Kadam S, Ecker JR, Emerson B, Hogenesch JB, Unterman T, Young RA, Montminy M. Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501076102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]