Abstract

Previous research suggests that women's early sexual victimization experiences may influence their parenting behaviors and increase the vulnerability of their children to being sexually victimized. The current study considered whether mother's sexual victimization experiences, in childhood and after age 14, were associated with the sexual victimization experiences reported by their adolescent daughters, and if so, whether these effects were mediated via parenting behaviors. The proposed model was examined using a community sample of 913 mothers and their college-bound daughters, recruited by telephone at the time of the daughter's high school graduation. Daughters reported on their experiences of adolescent sexual victimization and perceptions of mothers' parenting in four domains: connectedness, communication effectiveness, monitoring, and approval of sex. Mothers provided self-reports of their lifetime experiences of sexual victimization. Consistent with hypotheses, mothers' victimization was positively associated with their daughters' victimization. The effect of mothers' childhood sexual abuse was direct, whereas the effect of mothers' victimization after age 14 was mediated via daughters' perceptions of mothers' monitoring and greater approval of adolescent sexual activity. Comparison of the prevalence of specific victimization experiences indicated that mothers were more likely to report forcible rape over their lifetimes; however, daughters were more likely to report unwanted contact and incapacitated rape. Findings suggest that even in a highly functional community sample, mothers' sexual victimization experiences are significantly associated with aspects of their parenting behavior and with their daughters' own experiences of adolescent sexual victimization.

Introduction

A large body of research has established that sexual victimization in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood has lasting negative effects on a variety of outcomes including physical health (Elklit & Shevlin, 2010), sexual functioning (vanRoode, Dickson, Herbison, & Paul, 2009), and mental health, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance abuse (Burnam et al., 1988; Nelson et al., 2002). Early sexual victimization can also have lasting negative effects on parenting in adulthood (e.g., Noll, Trickett, Harris, & Putnam, 2009, see DiLillo, 2001 for a review). Poor parenting and family environments have wide-ranging negative effects on offspring (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002), which may result in another generation of children who are themselves sexually victimized. The current study explored the association between sexual victimization experiences of mothers and their adolescent daughters.

Multiple studies have documented that mothers who report sexual victimization during childhood or adolescence are more likely to have a child who has also experienced sexual abuse (e.g., Avery, Hutchinson, & Whitaker, 2002; Zuravin, McMillen, DePanfilis, & Risley-Curtis, 1996). These studies do not implicate mothers as responsible for their offspring's victimization, certainly not as the perpetrator. Rather, they typically are interpreted as indicative of negative consequences of sexual victimization (e.g., poverty, early pregnancy, depression, trauma symptoms, and substance use), which create a harmful environment for the child, thereby increasing the child's risk of victimization (Noll et al., 2009; Serbin & Karp, 2004). For example, McCloskey and Bailey (2000) found that the relationship between mother's sexual victimization and her child's sexual victimization was partially mediated via the mother's drug use.

A related body of research has considered the parenting attitudes and practices of women who were victimized in childhood (see Serbin & Karp, 2004 for a review). Mothers who experienced childhood victimization engaged in harsher and more physical punishment of their young children (DiLillo, Tremblay, & Peterson, 2000; Dubowitz et al., 2001), with studies implicating maternal depression as mediating the relationship between mother's CSA and later harsh parenting (Banyard, Williams, & Siegal, 2003; Mapp, 2010; Schuetze & Eiden, 2005). On the other hand, there is also some evidence that mothers who experienced early sexual victimization may be more permissive as parents and fail to set appropriate limits with their children (see DiLillo & Damashek, 2003 for a review). For example, Ruscio (2001) found an association between CSA and self-reported permissiveness in parenting and Kim, Trickett, and Putnam (2010) found that CSA was negatively associated with self-reported punitive discipline. Collin-Vezina, Cyr, Pauze, & McDuff (2005) found an indirect effect of mother's CSA on inconsistent discipline and monitoring of their school aged children that was mediated through maternal dissociation.

Most studies examining the effects of mother's sexual victimization on parenting and child outcomes have been restricted to preschool and pre-adolescent children. However, as children enter adolescence, the consequences of poor parenting may be particularly deleterious, and are associated with various negative outcomes such as increased sexual activity, substance use, and delinquency (Ary et al., 1999; Lac & Crano, 2009; Resnick et al., 1997). Specific to adolescent sexual behavior, reviews of the literature indicate that parental closeness, communication, and monitoring are all protective factors (Markham et al., 2010; Meschke, Bartholomae, & Zentall, 2002). Cavanaugh and Classen (2009) speculate that mothers who were sexually victimized in childhood or adolescence may exhibit deficits in parental communication (particularly about sex) and monitoring, which in turn increase the likelihood that the daughter will engage in sexually risky behaviors and experience sexual victimization herself. In addition, women with sexual victimization histories have been shown to have more liberal sexual attitudes (Meston, Heiman, & Trapnell, 1999), which, in turn have been positively associated with sexual behavior in adolescent children (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000; McNeely et al., 2002).

The current study examined the hypothesis that there would be a positive association between the sexual victimization experiences of mothers and those of their adolescent daughters. We were particularly interested in exploring putative mediators of this relationship, hypothesizing that mothers who were victimized would exhibit deficits in parenting behaviors, which would in turn be associated with sexual victimization among daughters. Based on relevant literature, we considered four parenting variables as potential mediators. First, we considered parental monitoring, which is protective against adolescent sexual risk behaviors (e.g., DiClemente et al., 2001; Graaf et al., 2010) and sexual victimization (Small & Kerns, 1993). We also considered the role of two other parenting variables which have been shown to be negatively associated with adolescent sexual activity: mother's communication effectiveness (e.g., Karofsky, Zeng, & Kosorok, 2001) and daughter's feelings of connectedness to her mother (e.g., feeling loved, Jaccard & Dittus, 2002; McNeely et al., 2002). Finally, we considered the mediating role of perceived maternal approval of adolescent sexual activity, since greater parental approval of sex has been positively associated with sexual activity among adolescents (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000; McNeely et al., 2002). We were able to consider the independent contributions of mother's CSA experiences as well as mother's unwanted sexual experiences after age 14. Given the nascent state of the literature, we offered no specific hypotheses regarding differential effects of these two types of victimization on these parenting factors.

Although the current data set was not originally designed to test these relationships, it provided some advantages in examining them relative to previous studies. Whereas many previous studies of the effects of maternal victimization on children have relied on samples of mothers or children who had been referred for services, the current sample of mothers and daughters was recruited from households in the community to take part in a study of transition to college. Thus, all daughters were the same age (seniors in high school) and the sample was highly functional. As a result, differences that emerge between victimized and non-victimized mothers can more readily be attributed to this experience.

The data also allowed us to compare the prevalence of lifetime sexual victimization reported by mothers with that reported by their adolescent daughters. Women are at highest risk of sexual assault between the ages of 16 and 19, with the risk decreasing with increasing age (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006). Accordingly, past year incidence of rape in a national college sample was much higher (5.15%) compared to a household sample of adult women (.94%, Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggierio, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007. However, even if risk of sexual victimization decreases over time, logically, rates of lifetime sexual victimization among older women should be at least as high as those of a college student. Accordingly, lifetime rate of rape was higher among adult women (18.0%) compared to college students (11.5%, Kilpatrick et al., 2007). On the other hand, whereas rape is a highly salient and memorable traumatic event that is unlikely to be forgotten with the passage of time, less severe forms of sexual victimization occurring many years earlier may be more difficult to recall. For example, in a representative household sample of women 18-30, rates of verbally coerced sexual contact were substantially lower than those reported in Koss et al's national college sample, despite the fact that the Testa sample was older (Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004). This intriguing finding led us to speculate that less severe victimization experiences may be forgotten or re-interpreted over time. The current data allowed us to compare rates of different types of sexual victimization experiences for adolescents versus adult women. We hypothesized that mothers would report higher rates of lifetime rape, but tentatively hypothesized that daughters would report higher rates of less severe types of victimization, such as unwanted contact, relative to mothers.

Method

Recruitment and subjects

Participants consisted of 913 adolescent females and their mothers who were recruited from households in Erie County, New York at the time of the daughter's high school graduation. At baseline, students were on average 18.1 (SD = 0.33) years old and mothers were 47.7 (SD = 4.78) years old. Most participants were Caucasian (91.5% students, 93.2% mothers, compared to 82.2% Caucasian for the county) and 75% of mothers had at least some college education. The majority of households included a mother and father (87.4%) and median household income was $75,000, which is comparable to a median family income of $74,000 for college freshmen nationally (Pryor, Hurtado, Saenz, Santos, & Korn, 2007). In the fall semester, the majority of students attended public colleges in Western New York, although over 100 different colleges were represented.

Students were selected at random from yearbook photos from local city (N = 5) and suburban (N = 16) high school graduating classes of 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007. They were located using public telephone directories and contacted by telephone. Students and their mothers were offered the opportunity to participate in a longitudinal study of transition to college. To be eligible, the graduating senior had to be planning to enter a 2 or 4 year college in the fall, live with her mother (or a mother figure, such as a grandmother), and both mother and daughter had to agree to participate and provide written informed consent. We were able to locate 1,345 of the 3,153 female students chosen from yearbook photos. Of these, 133 were ineligible (primarily because they were not planning to attend college in the fall) and 1,068 dyads (78.9%) agreed to participate. The current analyses include mother-daughter dyads who completed both baseline (T0) and first semester college (T1) assessments (N = 913).

Procedures

Baseline questionnaire booklets were mailed separately to mothers and daughters in May or June of senior year and completed booklets returned by postage-paid envelope. After completion, dyads were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (alcohol only intervention, alcohol + sexual risk intervention, control) and those assigned to an intervention condition were offered the opportunity to participate in a parent-based intervention. Intervention effects on daughter's college drinking and sexual victimization are published elsewhere (see Testa, Hoffman, Livingston, & Turrisi, 2010). Measures used in the current analysis, with the exception of mother's victimization measures, were assessed at baseline, prior to intervention. Intervention condition was not associated with the likelihood of mothers reporting any type of childhood sexual abuse, χ2 (2) = .80, p = .67, or later sexual victimization χ2 (2) = 0.09, p = .96, and hence is not considered further for the current analyses.

All dyads completed follow-up measures at the end of the daughter's first semester of college. Daughters were compensated $30 for completion of baseline (T0) questionnaires and $50 for T1 follow-up; mothers were paid $25 for T0 and $30 for T1 assessments. All procedures were approved by the Social and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University at Buffalo.

Measures

Mothers' monitoring

At baseline (T0), daughters completed a 5-item parental monitoring measure (Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2006). Items were phrased so as to be specific to the mother and included “How often do you tell your mother where you're going after school?”, “How often does your mother ask you where you're going?”, “How often do you tell your mother where you're really going when you go out evenings and weekends?”, “How often do you talk with your mother about plans you have made with your friends?” and “If you are going to be home late or change your plans, are you expected to call to let your mother know?” All items were rated on 5-point scales ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Mothers were asked corresponding questions regarding their monitoring and knowledge of their daughters' activities. Mothers (α =.73) and daughters reports (α =.75) were correlated (r = .43, p < .001); however, we used the daughter's report as the primary measure since prior research indicates that adolescent perception of parental behaviors is a better predictor of adolescent outcomes than parent self-reports (Jaccard & Dittus, 2002) and should be less subject to social desirability bias.

Mothers' communication effectiveness

At T0, daughters responded to 14 items, developed by Turrisi, Jaccard, Taki, Dunnam, and Grimes (2001) that assess the effectiveness of mother's communication including “My mother is a good listener” and “My mother says hurtful things to me” (reversed). These were rated on 5 point scales ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (most of the time). Mothers used the same scale to report on their own communication effectiveness. Mothers' (α =.82) and daughters' reports (α =.91) were correlated (r = .40, p < .001); however, we used daughters' reports.

Mothers' approval of daughters' sexual behaviors

At T0, daughters responded to 9 items, assessed on 7-point scales, that assessed perceived maternal approval of various sexual behaviors. Items followed the stem “How would your mother respond if she knew” and included “you had sex without a condom”, “you had sex with a long-term boyfriend” and “you planned to wait till marriage to have sex” (reversed). Mothers responded to the same items regarding their own responses to their daughter engaging in the various behaviors. The sum of daughters' items had reasonable internal consistency (α =.60) and was correlated (r = .35) with the comparable sum of mother's own self-reported approval (α =.68); daughters' reports were used in analyses.

Connectedness

Four items, assessed on 5-point scales, and derived from prior literature (e.g., Resnick et al., 1997) were used to measure the daughter's feelings of connectedness to her mother at T0. Items consisted of: “How close do you feel to your mother?”, “How much do you think your mother cares about you?”, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your relationship with your mother?”, and “How loved and wanted do you feel?” The items had good internal consistency (α =.85). There was no mother measure corresponding to this subjective construct.

Adolescent sexual victimization

At T0, daughters completed a 20-item revised version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (R-SES, Testa, Hoffman, & Livingston, 2010) that assessed unwanted sexual experiences since age 14. The measure expanded upon earlier versions of the SES (Koss, Gidycz, & Wisniewski, 1987; Testa et al., 2004) by crossing each of 4 perpetrator tactics (verbal coercion, threats of physical harm, force, incapacitation) with 5 outcomes (contact, attempted intercourse, completed vaginal intercourse, oral sex, and anal sex). Participants were asked how many times each of the following experiences occurred, with questions worded so that the tactic appeared before the outcome (Abbey, Parkhill, & Koss, 2005). As our primary dependent measure we used the count of the number of items reported (α = .83), which was Winsorized to reduce skewness by recoding values in the top 5% (7 to 20) to the 95th percentile value (7).

Mothers' sexual victimization

At T1, mothers completed the same 20-item Revised Sexual Experiences Scale regarding unwanted sexual experiences that occurred since age 14. Mothers responded yes or no according to whether each item had ever occurred. Our rationale for measuring victimization at follow-up rather than baseline was that we did not want to raise sensitive topics that might jeopardize mothers' willingness to participate in the intervention. Although we did not ask about the ages at which victimization experiences occurred, risk of sexual victimization is quite low for women in their 40's, with just 6% of rapes involving victims older than 29 (Kilpatrick, 1992). Thus, we assume that the majority of mothers' victimization experiences occurred prior to their daughter's adolescence. Items were summed (α = .87), and Winsorized to reduce skewness (i.e., sums greater than 7 were recoded to 7).

Mothers' childhood sexual abuse

Was assessed at T1 using 7 dichotomous items adapted from Whitmire, Harlow, Quina, and Morokoff (1999) and used by Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, and Livingston (2005). Women responded yes or no to behaviorally specific items describing unwanted sexual experiences occurring before age 14. These included contact (e.g., “person tried to touch you in a sexual way”), attempted penetration, and penetration. Items were summed to create a total CSA score (α =.80), and Winsorized to reduce skewness (i.e., sums greater than 5 were recoded to 5).

Mothers' demographics

Mothers reported on several demographic variables including age, marital status, family income, educational attainment, and number of children.

Results

Prevalence of sexual victimization

Before considering the indirect effects of mother's victimization on daughter's victimization, we compared the prevalence of different types of sexual victimization experiences for mothers and daughters. The revised SES measure, by crossing all tactics with all outcomes, can be scored to reveal the types of sexual victimization experiences reported, including contact, attempted coercion, coercion, attempted rape, and completed rape (see Testa et al., 2010 for scoring). Because of recent interest in incapacitated rape (i.e., penetration occurring when the woman is incapacitated by alcohol or drugs and unable to resist, Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Testa, Livingston, VanZile-Tamsen, & Frone, 2003), we considered completed forcible rape and incapacitated rape separately. Table 1 presents the proportion of mothers and daughters reporting each type of sexual victimization since age 14.

Table 1. Prevalence of Sexual Victimization Since Age 14 for Mothers and Daughters (N = 913).

| Type of victimization | Mothers | Daughters | χ2 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | |||

| Contact | 31.7 | 287 | 37.9 | 346 | 7.66 | .01 |

| Attempted coercion | 28.3 | 258 | 28.1 | 257 | 0.00 | .96 |

| Coercion | 17.1 | 156 | 17.7 | 162 | 0.13 | .72 |

| Attempted rape | 14.4 | 130 | 16.8 | 153 | 1.92 | .17 |

| Rape | 11.2 | 101 | 10.2 | 93 | 0.45 | .50 |

| Incapacitated rape | 4.3 | 39 | 7.2 | 66 | 7.09 | .01 |

| Forcible rape | 9.2 | 84 | 5.3 | 48 | 10.67 | .001 |

| Any victimization | 40.7 | 372 | 45.1 | 412 | 3.58 | .06 |

Note. Victimization experiences are not mutually exclusive. For each type, Mother and Daughter comparisons are made with independent samples chi-square tests with df = 1.

Treating mothers and daughters as independent samples, daughters were more likely than mothers to report unwanted contact χ2 (1) = 7.66, p = .01, consistent with our hypothesis. We had hypothesized that mothers would be more likely than daughters to report rape. Although mothers and daughters did not differ on reports of any type of rape, mothers were more likely than daughters to report forcible rape, χ2 (1) = 10.67, p = .001 whereas daughters were more likely to report incapacitated rape χ2 (1) = 7.09, p = .01. Using the McNemar Test for paired samples (Fleiss, 1973), the pattern of results within mother-daughter dyads was similar. Daughters were more likely than their mothers to report contact, χ2 (1) = 8.10, p = .004, and incapacitated rape, χ2 (1) = 6.97, p = .01, whereas mothers were more likely than their daughters to report forcible rape, χ2 (1) = 10.38, p = .001. A paired sample t-test revealed no difference in the number of items reported by daughters (M = 1.46, SD = 2.11) compared to mothers (M = 1.33, SD = 2.09), t (912) = 1.35, p = .18.

Childhood sexual abuse (prior to age 14) was reported by 31.5 % of mothers. This prevalence is comparable to estimates from general population samples (Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990; Kendler et al., 2000). Consistent with previous research (Roodman & Clum, 2001), mothers who experienced CSA were significantly more likely to report sexual victimization after age 14 (63.6%) than mothers without CSA (30.3%), χ2 (1) =89.98, p < .001.

Is mother's sexual victimization associated with daughter's sexual victimization?

We hypothesized that the daughters of mothers who experienced sexual victimization would be more likely to report victimization. Among mothers reporting CSA, 51.0% of their daughters reported victimization compared to 42.5% of daughters whose mothers did not report CSA, χ2 (1) =5.73, p < .03. Among mothers reporting victimization after age 14, 50.3% of daughters reported victimization compared to 41.6% of daughters of non-victimized mothers, χ2 (1) = 6.71, p < .02. However, when mother's CSA and victimization after 14 were entered simultaneously into a single logistic regression equation predicting whether daughter reported victimization, each was reduced to marginal significance, reflecting the high overlap between the 2 independent variables.

Previous research has shown that early victimization can result in early pregnancy, difficulties in intimate relationships, and lifelong deficits in educational attainment and income, which can conceivably increase the vulnerability of one's offspring to victimization (Serbin & Karp, 2004). To determine whether any of these variables could be accounting for the association between mothers' and daughters' victimization we examined whether victimized mothers differed from non-victimized mothers on educational attainment, income, age, current marital status, and number of children. There were no differences on any of these variables according to whether or not mothers had experienced CSA and likewise, no differences for women reporting victimization after age 14 compared to those not reporting such victimization. Thus, subsequent analyses were conducted without controlling for any of these variables. (Maternal mental health or depression may also mediate the effect of mothers' victimization on daughters' outcomes. At T0, we assessed current depressive symptoms for a subset of mothers (N = 569) using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff, 1977). CES-D symptoms were positively associated with maternal victimization after age 14, but not with CSA. When included in the model as a mediator, CES-D had no association with daughter's victimization (B = .00) and little effect on the substantive pattern of findings, weakening them only slightly.)

Does mother's parenting mediate the relationship between mother and daughter victimization?

We hypothesized that to the extent that mother's victimization increases the likelihood of daughter's victimization, this effect would be mediated via several parenting mechanisms: mother's communication effectiveness, monitoring, connectedness, and approval of daughter's sexual behavior. To test this indirect effects model, we conducted path analyses with OLS regression using the continuous measures of mother's CSA and later sexual victimization, as well as the continuous measure of daughter's sexual victimization. The effects of CSA and later victimization were considered simultaneously. To test for mediation, we used the joint significance test of the paths from the independent variable to the mediator, and from the mediator to the outcome. This test has been shown to have the most power and the most conservative Type I error rate compared with other methods of testing indirect effects (MacKinnon et al., 2002). If both of the component direct paths in the path jointly show significance at the .05 level, then there is evidence for a significant indirect or mediating effect through that mediator. This test was applied to each of the hypothesized mediators.

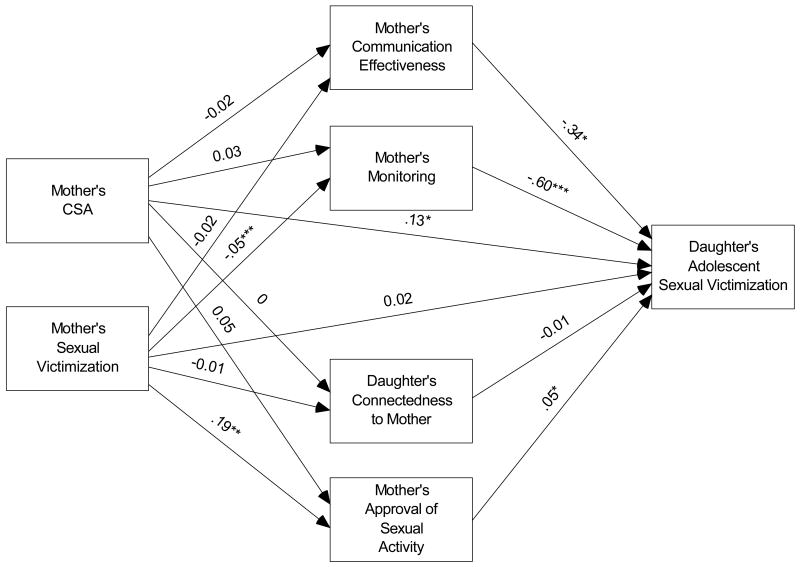

The correlations among the variables in the path model are presented in Table 2. As shown in Figure 1, there were significant indirect effects of mother's sexual victimization after age 14 on daughter's sexual victimization that were mediated via lower perceived monitoring and greater perceived approval of sex. Mother's CSA did not significantly predict any of the parenting measures; however, there was a significant direct effect of mother's CSA on daughter's sexual victimization that remained significant even with the mediators in the model (b = .13, p < .05). In addition, perceived mother's communication effectiveness was protective against daughters' sexual victimization (b = -.34, p < .05) but was not associated with mothers' victimization. When the model predicting daughters' victimization included only the two mothers' victimization variables, R2 was 0.02; however, the addition of the four mediators significantly increased the explained variance, ΔR2 = 0.07, F (4,899) = 17.06, p < .001.

Table 2. Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Variables in the Path Model (N = 906).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mother's CSA | – | ||||||

| 2. Mother's sexual victimization | .37*** | – | |||||

| 3. Mother's communication effectiveness | -.06 | -.06 | – | ||||

| 4. Mother's monitoring | .01 | -.13*** | .36*** | – | |||

| 5. Daughter's connectedness to mother | -.01 | -.02 | .79*** | . 38*** | – | ||

| 6. Mother's approval of sexual activity | .06 | .11** | .03 | -.11** | .02 | – | |

| 7. Daughter's sexual victimization | .11** | .10** | -.19*** | -.23*** | -.17*** | .11** | – |

| M | 0.76 | 1.34 | 3.59 | 4.25 | 4.29 | 12.27 | 1.47 |

| SD | 1.36 | 2.08 | 0.77 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 3.72 | 2.12 |

Note. CSA = Childhood Sexual Abuse. Mother's communication, monitoring, connectedness and approval of sexual activity based on daughter's reports.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Path model of hypothesized parenting mechanisms as mediators of the effect of Mother's victimization on Daughter's victimization. Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown. N = 906. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The path model as a whole explained a significant amount of variance, R2 = 0.08, F (6,899) = 13.76, p < .001.

To increase confidence in the findings, we repeated the analysis substituting mothers' reports of their own monitoring, communication effectiveness, and approval of sex for the daughters' versions of these variables. The mediated effect of victimization via monitoring and the direct effect of CSA remained; however, the effects of communication and approval of sex were no longer significant. The model explained a similar amount of variance in the outcome (R2 = 0.09, F(6,737) = 11.70, p < .001), and again the addition of the mediators significantly increased the explained variance over that explained by mothers' victimization (ΔR2 = 0.08, F(4,737) = 15.61, p < .001).

Discussion

The current study considered whether mother's childhood and adult sexual victimization experiences are associated with their daughters'experiences of adolescent sexual victimization. Results provide some support for hypotheses. First, mothers' childhood sexual abuse experiences and experiences occurring after age 14 modestly but significantly increased the likelihood that their adolescent daughters would report adolescent sexual victimization. Importantly, we found indirect effects of mother's victimization on some parenting measures, which in turn predicted daughter's victimization, providing some support for our model. Consistent with prior research suggesting greater permissiveness among parents who had been victimized as children (e.g., DiLillo & Damashek, 2003), mothers who reported sexual victimization after age 14 were viewed by their daughters as more approving of sexual activity and less aware of their daughter's activities. Accordingly, and also consistent with previous research (e.g., Dittus & Jaccard, 2000; Markham et al., 2010), these parenting variables were associated with daughters' sexual victimization.

It is not completely clear why victimized mothers would be perceived by their daughters as more liberal in their attitudes and providing less monitoring. Given that parenting practices have been shown to be transmitted across generations (e.g., Bailey, Hill, Oesterle, & Hawkins, 2009) it is plausible that victimized mothers experienced more permissive parenting when growing up, which they learned and replicated with their own children. It is also possible that women who were victimized in adolescence or early adulthood were and remain more accepting of risk-taking behaviors, for themselves and others. Importantly, the effects of victimization on parenting did not extend to all of the hypothesized mediating variables. Daughters of victimized mothers did not view their mothers as less effective communicators nor did they feel less connected to their mothers compared to daughters of nonvictimized mothers. Although the observed pattern may be specific to this particular sample of high functioning women or to the measures we used, the finding that victimized women exhibit specific rather than universal parenting deficits is a potentially important one that should be explored further.

The current study was unique in that the effects of mothers' childhood sexual abuse and victimization after age 14 were considered separately but simultaneously. Not surprisingly, CSA was strongly associated with mothers' later victimization (e.g., Noll, 2005). However, when considered together, there were differential effects of mothers' childhood versus later sexual victimization. In contrast to the indirect effects of victimization after age 14, the effect of mother's CSA on daughter's victimization was not mediated by any of the parenting variables that we considered. However, because a mother's childhood victimization cannot directly cause her daughter to be victimized, this direct effect presumably reflects the effect of an unmeasured mediational pathway or a third variable (e.g, family or neighborhood environment). Although caution is necessary in interpreting these novel results given the strong association between mothers' CSA and victimization after age 14, findings serve as a reminder that different types of victimization may reflect and result in different risk factors and should not be assumed to be equivalent.

We acknowledge that we have simplified what is no doubt an extremely complex process, for example, there are many additional potential mediating variables, such as trauma symptoms and interpersonal difficulties (e.g., DiLillo, Lewis, & DiLoreto-Colgan, 2007; Rumstein-McKean & Hunsley, 2001) as well as many potential moderating variables (e.g., Walsh, Fortier, & DiLillo, 2010) that were not considered. It is also possible that the relationship between mother and daughter victimization is spurious. Although victimized and non-victimized mothers did not differ on several variables likely to be associated with parenting, it is possible that we failed to account for an unmeasured variable. Finally, we acknowledge that given our causal model, it would have been optimal to assess mothers' lifetime victimization prior to assessment of daughters' victimization and perceived parenting, or to have assessed the ages at which victimization experiences occurred. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that mothers were victimized after their daughters were victimized, the low incidence of sexual victimization among women over 30 (Kilpatrick, 1992; Kilpatrick et al., 2007) makes this unlikely.

A secondary aim of the study was to compare the prevalence of lifetime sexual victimization for mothers and daughters. We found some support for the intriguing paradox by which older women are less likely to report certain types of lifetime sexual victimization---sexual contact and incapacitated rape---than are younger women, despite the fact that with increasing age comes more opportunities in which to be victimized. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that this particular cohort actually experienced fewer of these victimization experiences than their adolescent daughters, this is unlikely for several reasons. First, the average age of mothers in this sample would make them college-aged during the 1980s, at the time Koss et al.'s (1987) national college study revealed high rates of sexual victimization (e.g., 44% reported verbally coerced contact) that have continued to this day. Second, many studies have shown that a substantial proportion of adults with documented early sexual victimization fail to report it when asked about it many years later (Fergusson, Horwood, & Woodward, 2000; Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Widom & Morris, 1997). Although we are unable to compare current with earlier reports, this body of research suggests that mothers' reports of victimization are likely to underreport actual experiences, which may have occurred 30 or more years earlier. Findings support our a priori hypothesis that decay in memory and underreporting are more likely to apply to less serious or more ambiguous experiences (contact, incapacitated rape) than to forcible rape, the most severe and traumatic type of sexual victimization. Although more rigorous research is necessary, we urge caution when using the SES to assess lifetime sexual victimization experiences among older women, given that the measure has been validated using college and young adult samples (Koss et al., 2007).

We consider these findings to be exploratory, given that the study was not explicitly designed for optimal testing of these relationships. Nonetheless, it is quite striking that even among this highly functional sample of mothers, there appear to be lasting effects of early victimization which exert a modest but significant effect on their parenting and consequently on the likelihood of victimization among their adolescent children. Findings support previous calls to provide intervention for sexually victimized girls and women to prevent negative consequences (MacMillan et al., 2009). They also serve as a reminder of the importance of parenting behaviors on adolescent outcomes and support the need for parent-based interventions to prevent adolescent risk behaviors (e.g., Meschke et al., 2002).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01 AA014514 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, Koss MP. The effects of frame of reference on responses to questions about sexual assault victimization and perpetration. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:364–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ary DV, Duncan TE, Biglan A, Metzler CW, Noell JW, Smolkowski K. Development of adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:141–150. doi: 10.1023/a:1021963531607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, Hutchinson D, Whitaker K. Domestic violence and intergenerational rates of child sexual abuse: A case record analysis. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2002;19:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, Hawkins JD. Parenting practices and problem behavior across three generations: Monitoring, harsh discipline, and drug use in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1214–1226. doi: 10.1037/a0016129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegal JA. The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:334–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2006;68:1084–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Justice Statistics. Criminal victimization in the United States, 2005 statistical tables, National Crime Victimization Survey NCJ 215244. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Stein JA, Golding JM, Siegel JM, Sorenson SB, Forsythe AB, Telles CA. Sexual assault and mental disorders in a community population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh CE, Classen CC. Intergenerational pathways linking childhood sexual abuse to HIV risk among women. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2009;10:151–169. doi: 10.1080/15299730802624536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin-Vezina D, Cyr M, Pauze R, McDuff P. The role of depression and dissociation in the link between childhood sexual abuse and later parental practices. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2005;6:71–97. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Sionean C, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Davies S, Hook EW, Oh MK. Parental monitoring: Association with adolescents' risk behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1363–1368. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D. Interpersonal functioning among women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse: Empirical findings and methodological issues. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:553–576. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Damashek A. Parenting characteristics of women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:319–333. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Lewis T, DiLoreto-Colgan A. Child maltreatment history and subsequent romantic relationships: Exploring a psychological route to dyadic difficulties. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2007;15:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Tremblay GC, Peterson L. Linking childhood sexual abuse and abusive parenting: The mediating role of maternal anger. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:767–779. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittus PJ, Jaccard J. Adolescents' perceptions of maternal disapproval of sex: Relationship to sexual outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26:268–278. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Black MM, Kerr MA, Hussey JM, Morrel TM, Deverson MD, Starr RH. Type and timing of mothers' victimization: Effects on mothers and children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:728–735. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elklit A, Shevlin M. General practice utilization after sexual victimization: A case control study. Violence Against Women. 2010;16:280–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801209359531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Hotaling G, Lewis IA, Smith C. Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. New York: Wiley; 1973. pp. 73–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Woodward LJ. The stability of child abuse reports: A longitudinal study of the reporting behaviour of young adults. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:529–544. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graaf H, Vanwesenbeeck I, Woertman L, Keijsers L, Meijer S, Meeus W. Parental support and knowledge and adolescents' sexual health: Testing two mediational models in a national Dutch sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:189–198. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ. Adolescent perceptions of maternal approval of birth control and sexual risk behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;90:1426–1430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karofsky PS, Zeng L, Kosorok MR. Relationship between adolescent–parental communication and initiation of first intercourse by adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:41–45. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, Hettema JM, Myers J, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women: An epidemiological and cotwin control analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Edmunds CN, Seymour AK. Rape in America: A report to the nation. Arlington, VA: National Victim Center and Medical University of South Carolina; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggierio KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. Charleston, SC: Medical University of South Carolina. National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Childhood experiences of sexual abuse and later parenting practices among non-offending mothers of sexually abused and comparison girls. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:610–622. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, Ullman SE, West CM, White JW. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lac A, Crano W. Monitoring matters: Meta-analytic review reveals the reliable linkage of parental monitoring with adolescent marijuana use. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4:578–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN. Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapp SC. The effects of sexual abuse as a child on the risk of mothers physically abusing their children: A path analysis using systems theory. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;30:1293–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, Peskin MF, Flores B, Low B, House LD. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:S23–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey LA, Bailey JA. The intergenerational transmission of risk for child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:1019–1035. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely C, Shew ML, Beuhring T, Sieving R, Miller BC, Blum RW. Mothers' influence on the timing of first sex among 14- and 15-year-olds. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:256–265. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschke LL, Bartholomae S, Zentall SR. Adolescent sexuality and parent-adolescent processes: Promoting healthy teen choices. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:264–279. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meston CM, Heiman JR, Trapnell PD. The relation between early abuse and adult sexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 1999;36:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Cooper ML, Dinwiddie SH, Bucholz KK, Glowinski A, McLaughlin T, Dunne MP, Statham DJ, Martin NG. Association between self-reported childhood sexual abuse and adverse psychosocial outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:139–145. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG. Does childhood sexual abuse set in motion a cycle of violence against women? What we know and what we need to learn. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:455–462. doi: 10.1177/0886260504267756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, Harris WW, Putnam FW. The cumulative burden borne by offspring whose mothers were sexually abused as children: Descriptive results from a multigenerational study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:424–449. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JH, Hurtado S, Saenz VB, Santos JL, Korn WS. American freshman: Forty-year trends 1966-2006. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute. University of California, Los Angeles; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving RE, Shew M, Bearinger LH, Udry RJ. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman AA, Clum GA. Revictimization rates and method variance: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:183–204. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumstein-McKean O, Hunsley J. Interpersonal and family functioning of female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:471–490. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM. Predicting the child-rearing practices of mothers sexually abused in childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:369–387. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze P, Eiden RD. The relationship between sexual abuse during childhood and parenting outcomes: Modeling direct and indirect pathways. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbin LA, Karp J. The intergenerational transfer of psychosocial risk: Mediators of vulnerability and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004;55:333–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Kerns D. Unwanted sexual activity among peers during early and middle adolescence: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:941–952. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA. Alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as mediators of the sexual victimization–revictimization relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:249–259. doi: 10.1037/a0018914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA, Turrisi R. Preventing college women's sexual victimization through parent-based intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science. 2010;11:308–318. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0168-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, VanZile-Tamsen C, Frone MR. The role of women's substance use in vulnerability to forcible and incapacitated rape. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:756–764. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA. Childhood sexual abuse, relationship satisfaction, and sexual risk taking in a community sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1116–1124. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women's experiences of sexual aggression using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanRoode T, Dickson N, Herbison P, Paul C. Child sexual abuse and persistence of risky sexual behaviors and negative sexual outcomes over adulthood: Findings from a birth cohort. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2009;33:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Fortier MA, DiLillo D. Adult coping with childhood sexual abuse: A theoretical and empirical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010;15:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmire LE, Harlow LL, Quina K, Morokoff PJ. Childhood trauma and HIV. Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Morris S. Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization: Part 2. Childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zuravin S, McMillen C, DePanfilis D, Risley-Curtis C. The intergenerational cycle of child maltreatment: Continuity versus discontinuity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11:315–334. [Google Scholar]