Abstract

Angiotensin subtype-1 receptor (AT1R) influences inflammatory processes through enhancing signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins 3 (STAT3) signal transduction, resulting in increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production. Although angiotensin subtype-2 receptor (AT2R), in general, antagonizes AT1R-stimulated activity, it is not known if AT2R has any anti-inflammatory effects. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that AT2R activation plays an anti-inflammatory role by reducing STAT3 phosphorylation and TNF-α production. Changes in AT2R expression, TNF-α production, and STAT3 phosphorylation were quantified by Western blotting, Bio-Plex cytokine, and phosphoprotein cellular signaling assays in PC12W cells that express AT2R but not AT1R, in response to the AT2R agonist, CGP-42112 (CGP, 100 nm), or AT2R antagonist PD-123319 (PD, 1 μm). A 100% increase in AT2R expression in response to stimulation with its agonist CGP was observed. Further, AT2R activation reduced TNF-α production by 39% and STAT3 phosphorylation by 83%. In contrast, PD decreased AT2R expression by 76%, increased TNF-α production by 84%, and increased STAT3 phosphorylation by 67%. These findings suggest that increased AT2R expression may play a role in the observed decrease in inflammatory pathway activation through decreased TNF-α production and STAT3 signaling. Restoration of AT2R expression and/or its activation constitute a potentially novel therapeutic target for the management of inflammatory processes.

Chronic activation of inflammatory pathways likely influences the pathogenesis of many common and disabling diseases in older adults, including cardiovascular diseases, inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, neurodegenerative conditions, infection, and cancer (Fujita and others 1996; Ershler and Keller 2000; Maggio and others 2006). The role of the renin–angiotensin system in the development of chronic inflammation observed in older adults is still being elucidated. Angiotensin II (Ang II) acts through 2 G-protein-coupled receptor subtypes: angiotensin subtype-1 receptor (AT1R) and angiotensin subtype-2 receptor (AT2R). These receptors have substantial differences in tissue distribution and intracellular signaling pathways (Carey and Siragy 2003). The activation of AT1R leads to a powerful pro-inflammatory effect (Suzuki and others 2003), induction of reactive oxygen species (Nickenig and Harrison 2002), hypertrophy, and apoptosis (Bascands and others 2001) and stimulation of fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis (Cipollone and others 2004). By contrast, AT2R exerts effects that are the opposite of AT1R, including anti-inflammatory (Matsubara 1998), anti-proliferative (Matsubara 1998), and anti-apoptotic actions (Bascands and others 2001).

Although blocking AT1R results in decreased production of the tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in vitro (Hahn and others 1994; Beasley 1997; Han and others 1999; Tsutamoto and others 2000; Siragy and others 2003), it is unclear whether this results from direct inhibition of AT1R or indirectly via unopposed AT2R activation.

Ang II activates signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins 3 (STAT3) via AT1R (Omura and others 2000). STAT3 is a key signal transduction protein that mediates cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation, and tumor cell evasion of the immune system (Costantino and Barlocco 2008). Binding sites have been identified for STAT3 within the promoter region of TNF-α (Chappell and others 2000). Mutation of the 3 base pairs of the STAT3 binding site had considerable effects on TNF-α promoter activity, demonstrating that STAT3 upregulates TNF-α expression (Chappell and others 2000). Given this and the lack of knowledge as to how AT2R influences inflammatory processes, we set out to determine the role of AT2R activation in inflammation. We hypothesized that stimulation of AT2R decreases TNF-α production through altered STAT3 signaling. We tested this hypothesis using PC12W cells that exclusively express AT2R in the absence of AT1R, to exclude the effects of any crosstalk between AT1R and AT2R on STAT3 signaling and TNF-α production (Omura and others 2000).

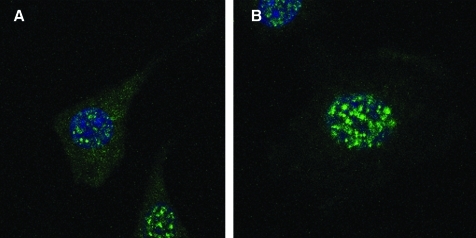

Northern and Western blot analyses were used to validate that AT1R are not expressed in PC12W cells (data not shown). The Biorad Radiance 2100 laser scanning confocal/multiphoton microscopy system (Mills and others 2003) was utilized to identify AT2R on the cell membrane and in the perinuclear and nuclear region of serum-starved PC12W cells (Fig. 1). The system consists of a Nikon TE300 epifluorescence microscope, a Plan Fluor 100 × NA 1.4 oil immersion objective lens, argon ion laser (457,488,514), HeNe 543, and 633 nm (www.cellscience.bio-rad.com). The anti-receptor antibodies for AT2R reacted specifically with AT2R (Ozono and others 1997, 2000; Wang and others 1998). AT2R antibodies were labeled with Alexa fluorophores 488 to demonstrate localization of AT2R using confocal microscopy with higher spatial resolution beyond the limits of conventional microscopy. Images are representative of 3 experiments.

FIG. 1.

Laser scanning confocal images of AT2R in PC12W cells, (A) and (B) 100 × magnification. Green fluorescent labeling for the AT2R was detected on the cell membrane and in the nuclear and perinuclear region of the PC12W cells. AT2R, angiotensin subtype-2 receptor.

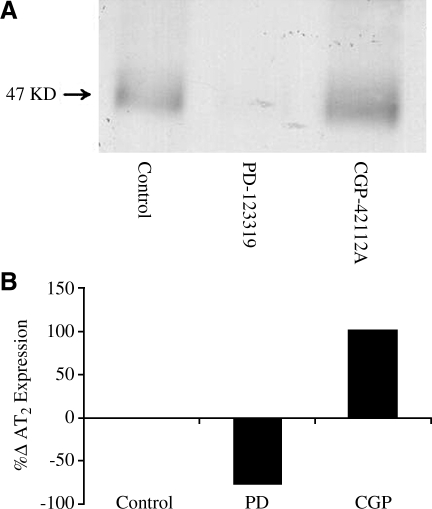

To determine the percentage change in AT2R expression after administration of AT2R agonist CGP-42112A or antagonist PD-123319, PC12W cells were treated with AT2R agonist CGP42112 (CGP) 100 nm or antagonist PD123319 (PD) 1 μm for 24 h. Western immunoblot detection with anti-AT2R in PC12W cells was used to quantify protein expression. Differences between groups were quantified using densitometry (Bio Rad GS-670 Imaging Densitometer). Stimulation of AT2R led to an ∼100% increase in the expression of AT2R, whereas inhibition led to a 76% decrease in expression of AT2R (Fig. 2A, B). Previous studies demonstrated an increase in AT2R expression during this receptor stimulation with Ang II (Shibata and others 1997; Zahradka and others 1998). AT2R stimulation seems to increase the AT2R gene promoter activity, an effect that was prevented by AT2R blockade with PD (De Paolis and others 1999). Our current study is consistent with these previous studies and confirms that AT2R stimulation enhances its gene activity. Thus, AT2R stimulation may have a positive feedback on its expression.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot quantification (A) of AT2R expression in response to AT2R agonist CGP-42112A (CGP, 100 nmol, □) or AT2R antagonist PD-123319 (PD, 1 μmol, ▪) for 24 h using immunoblot detection with anti-AT2R in PC12W cells. Bar graphs (B) represent the means of the band densities expressed as percentage change from control. Blots are representative of 3 experiments.

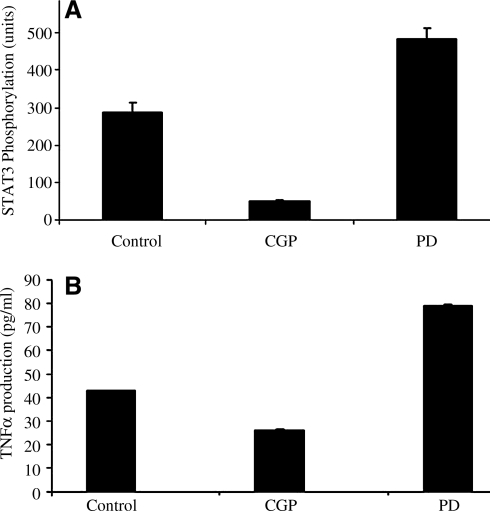

To determine whether direct AT2R stimulation influences STAT3 phosphorylation, PC12W cells were treated with AT2R agonist CCGP42112A (CGP, 100 nmol), or AT2R antagonist PD123319 (PD, 1 μmol) for 24 h. STAT3 phorphorylation status was determined using bead-based multiplex Luminex xMAP technology assays (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) to directly detect phosphorylated proteins STAT3 in lysates derived from cell culture using highly specific antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA). Data from the reaction were acquired using the Bio-Plex suspension array system. Activation of AT2R was associated with 83% decrease in phosphorylation of STAT3 (288 ± 24 U at base line to 49 ± 4 U), whereas inhibition was associated with a 68% increase in STAT3 phosphorylation (288 ± 24 U baseline to 484 ± 28 U [P < 0.0001]) (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Change in STAT3 phosphorylation in response to treatment with the AT2R agonist CGP42112A (CGP, 100 nmol) or AT2R antagonist PD123319 (PD, 1 μmol) for 24 h. Data acquired using the Bio-Plex suspension array system. (B) Change in the production of TNF-α in PC12W cells in response to AT2R agonist CGP-42112A (CGP, 100 nmol) or AT2R antagonist PD-123319 (PD, 1 μmol) for 24 h. Data shown are average of 3 experiments. STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins 3; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

To demonstrate the effects of AT2R agonist or antagonist on the production of TNF-α. The production of TNF-α was measured using Bio-Plex cytokine bead-based assays (xMAP technology) involving diverse matrices that are designed to quantify multiple cytokines. PC12W cells were incubated with AT2R agonists or antagonists for 24 h, lysed, and centrifuged as per the manufacturer's protocol. Using these 96-well-plate-format assays, we profiled the production of TNF-α. Data from the reaction were acquired using the Bio-Plex suspension array system described above. CGP-42112A stimulation of AT2R led to a 39% reduction of TNF-α production as compared to the control (42.79 ± 0.179 pg/mL to 26 ± 0.56 pg/mL; P < 0.0001). Inhibition of AT2R caused an 84% increase in TNF-α production (42.79 ± 0.179 pg/mL to 78.82 ± 0.71 pg/mL; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3B).

In this study we demonstrated that stimulation of AT2R in AT1R-deficient PC12W cells with an AT2R agonist upregulates receptor expression level, reduces STAT3 phosphorylation, and reduces TNF-α production. Further, specific antagonism of these same receptors results in decreased AT2R expression, increased STAT3 phosphorylation, and increased TNF-α production. This result suggests that AT2R, like AT1R, may be important in modulating inflammatory pathway activation, and that alterations in ratio of AT2R to AT1R may play an important role in chronic inflammatory pathway activation such as those observed in some older adults (Warnholtz and others 1999; Siragy and others 2003; Suzuki and others 2003).

The findings related to STAT3 phosphorylation and TNF-α production are supported by previously published reports demonstrating that mutations of the STAT3 binding sites have considerable effects on the promoter region of TNF-α (Chappell and others 2000). Also, TNF-α induces the tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of STAT3 (Guo and others 1998; Miscia and others 2002), suggesting a positive feedback mechanism. Our data that AT2R stimulation decreases TNF-α expression fit well with AT2R's presumed vasodilator and cardiovascular protective effects (Siragy and Carey 1999; Siragy and others 2000). Given that the PC12W cells are devoid of AT1R, the observed effects of stimulation or blockade of AT2R are receptor-specific and cannot be a result of a receptor cross-talk with the AT1R.

Previous studies confirmed that AT1R blockade increases AT2R activity in vivo (Weber 1992; Guan and others 1996), leading to decreased remodeling and cardiac fibrosis, which were completely abolished by simultaneous AT2R blockade. This suggests that such effects are the result of AT2R activation rather than AT1R blockade (Barber and others 1999; Siragy and others 2000; Carey and others 2001; Oishi and others 2006). This also supports a potential role for AT1R blockers to modulate inflammatory pathways through upregulating AT2R.

In conclusion, we provide first evidence that AT2R modulates STAT3 signaling and TNF-α production in a cell line devoid of AT1R. Further studies in cell lines with AT1R or in animal models are necessary to further understand the interactions between these receptor subtypes and inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants DK-078757 and HL091535 from the National Institutes of Health to Helmy M. Siragy, M.D., and by Johns Hopkins CSA and P30 AG021334 to Dr. Abadir and T. Franklin Williams to Dr. Abadir.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Barber MN. Sampey DB. Widdop RE. AT(2) receptor stimulation enhances antihypertensive effect of AT(1) receptor antagonist in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1999;34(5):1112–1116. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.5.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bascands JL. Girolami JP. Troly M. Escargueil-Blanc I. Nazzal D. Salvayre R. Blaes N. Angiotensin II induces phenotype-dependent apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 2001;38(6):1294–1299. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.096540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beasley D. Phorbol ester and interleukin-1 induce interleukin-6 gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via independent pathways. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1997;29(3):323–330. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199703000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM. Howell NL. Jin XH. Siragy HM. Angiotensin type 2 receptor-mediated hypotension in angiotensin type-1 receptor-blocked rats. Hypertension. 2001;38(6):1272–1277. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.096576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey RM. Siragy HM. Newly recognized components of the renin-angiotensin system: potential roles in cardiovascular and renal regulation. Endocr Rev. 2003;24(3):261–271. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell VL. Le LX. LaGrone L. Mileski WJ. Stat proteins play a role in tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression. Shock. 2000;14(3):400–402. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00027. discussion 402–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollone F. Fazia M. Iezzi A. Pini B. Cuccurullo C. Zucchelli M. de Cesare D. Ucchino S. Spigonardo F. De Luca M. Blockade of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor stabilizes atherosclerotic plaques in humans by inhibiting prostaglandin E2-dependent matrix metalloproteinase activity. Circulation. 2004;109(12):1482–1488. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121735.52471.AC. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino L. Barlocco D. STAT 3 as a target for cancer drug discovery. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(9):834–843. doi: 10.2174/092986708783955464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paolis P. Porcellini A. Gigante B. Giliberti R. Lombardi A. Savoia C. Rubattu S. Volpe M. Modulation of the AT2 subtype receptor gene activation and expression by the AT1 receptor in endothelial cells. J Hypertens. 1999;17(12 Pt 2):1873–1877. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917121-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ershler WB. Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita J. Tsujinaka T. Ebisui C. Yano M. Shiozaki H. Katsume A. Ohsugi Y. Monden M. Role of interleukin-6 in skeletal muscle protein breakdown and cathepsin activity in vivo. Eur Surg Res. 1996;28(5):361–366. doi: 10.1159/000129477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan H. Cachofeiro V. Pucci ML. Kaminski PM. Wolin MS. Nasjletti A. Nitric oxide and the depressor response to angiotensin blockade in hypertension. Hypertension. 1996;27(1):19–24. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D. Dunbar JD. Yang CH. Pfeffer LM. Donner DB. Induction of Jak/STAT signaling by activation of the type 1 TNF receptor. J Immunol. 1998;160(6):2742–2750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn AW. Jonas U. Buhler FR. Resink TJ. Activation of human peripheral monocytes by angiotensin II. FEBS Lett. 1994;347(2–3):178–180. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y. Runge MS. Brasier AR. Angiotensin II induces interleukin-6 transcription in vascular smooth muscle cells through pleiotropic activation of nuclear factor-kappa B transcription factors. Circ Res. 1999;84(6):695–703. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio M. Guralnik JM. Longo DL. Ferrucci L. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: a magnificent pathway. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(6):575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara H. Pathophysiological role of angiotensin II type 2 receptor in cardiovascular and renal diseases. Circ Res. 1998;83(12):1182–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.12.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills JD. Stone JR. Rubin DG. Melon DE. Okonkwo DO. Periasamy A. Helm GA. Illuminating protein interactions in tissue using confocal and two-photon excitation fluorescent resonance energy transfer microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2003;8(3):347–356. doi: 10.1117/1.1584443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miscia S. Marchisio M. Grilli A. Di Valerio V. Centurione L. Sabatino G. Garaci F. Zauli G. Bonvini E. Di Baldassarre A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) activates Jak1/Stat3-Stat5B signaling through TNFR-1 in human B cells. Cell Growth Differ. 2002;13(1):13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G. Harrison DG. The AT(1)-type angiotensin receptor in oxidative stress and atherogenesis: part I: oxidative stress and atherogenesis. Circulation. 2002;105(3):393–396. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi Y. Ozono R. Yoshizumi M. Akishita M. Horiuchi M. Oshima T. AT2 receptor mediates the cardioprotective effects of AT1 receptor antagonist in post-myocardial infarction remodeling. Life Sci. 2006;80(1):82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omura T. Yoshiyama M. Takeuchi K. Kim S. Iwao H. Yamagishi H. Toda I. Teragaki M. Akioka K. Yoshikawa J. Angiotensin blockade inhibits SIF DNA binding activities via STAT3 after myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32(1):23–33. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozono R. Matsumoto T. Shingu T. Oshima T. Teranishi Y. Kambe M. Matsuura H. Kajiyama G. Wang ZQ. Moore AF. Expression and localization of angiotensin subtype receptor proteins in the hypertensive rat heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278(3):R781–R789. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.3.R781. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozono R. Wang ZQ. Moore AF. Inagami T. Siragy HM. Carey RM. Expression of the subtype 2 angiotensin (AT2) receptor protein in rat kidney. Hypertension. 1997;30(5):1238–1246. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K. Makino I. Shibaguchi H. Niwa M. Katsuragi T. Furukawa T. Up-regulation of angiotensin type 2 receptor mRNA by angiotensin II in rat cortical cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239(2):633–637. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragy HM. Awad A. Abadir P. Webb R. The angiotensin II type 1 receptor mediates renal interstitial content of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in diabetic rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144(6):2229–2233. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragy HM. Carey RM. Protective role of the angiotensin AT2 receptor in a renal wrap hypertension model. Hypertension. 1999;33(5):1237–1242. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siragy HM. de Gasparo M. Carey RM. Angiotensin type 2 receptor mediates valsartan-induced hypotension in conscious rats. Hypertension. 2000;35(5):1074–1077. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.5.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y. Ruiz-Ortega M. Lorenzo O. Ruperez M. Esteban V. Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35(6):881–900. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutamoto T. Wada A. Maeda K. Mabuchi N. Hayashi M. Tsutsui T. Ohnishi M. Sawaki M. Fujii M. Matsumoto T. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist decreases plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6 and soluble adhesion molecules in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(3):714–721. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00594-x. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ. Moore AF. Ozono R. Siragy HM. Carey RM. Immunolocalization of subtype 2 angiotensin II (AT2) receptor protein in rat heart. Hypertension. 1998;32(1):78–83. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnholtz A. Nickenig G. Schulz E. Macharzina R. Brasen JH. Skatchkov M. Heitzer T. Stasch JP. Griendling KK. Harrison DG. Increased NADH-oxidase-mediated superoxide production in the early stages of atherosclerosis: evidence for involvement of the renin-angiotensin system. Circulation. 1999;99(15):2027–2033. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.15.2027. others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber MA. Clinical experience with the angiotensin II receptor antagonist losartan. A preliminary report. Am J Hypertens. 1992;5(12 Pt 2):247S–251S. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.12.247s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahradka P. Yau L. Lalonde C. Buchko J. Thomas S. Werner J. Nguyen M. Saward L. Modulation of the vascular smooth muscle angiotensin subtype 2 (AT2) receptor by angiotensin II. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252(2):476–80. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]