Abstract

Reduction in the amount of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in corticostriatal afferents is thought to contribute to the vulnerability of medium spiny striatal neurons in Huntington’s disease. In young Bdnf heterozygous (+/−) mice, striatal medium spiny neurons express less preprodynorphin, preproenkephalin, and D3 receptor mRNA than wildtype mice. Further, in aged Bdnf+/− mice, opioid, trkB receptor, and glutamic acid decarboxylase gene expression, and the number of dendritic spines on medium spiny neurons are more affected than in wildtype or younger Bdnf+/− mice. In this study, the possibility that intrastriatal infusions of BDNF would elevate gene expression in the striatum of Bdnf+/− mice was investigated. Wildtype and Bdnf+/− mice received a single, bilateral microinjection of BDNF or PBS into the dorsal striatum. Mice were sacrificed 24 hours later and semi-quantitative in situ hybridization histochemical analysis confirmed that preprodynorphin, preproenkephalin and D3 receptor mRNA was less in the caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens core of Bdnf+/− mice than in wildtype mice. A BDNF infusion increased preprodynorphin mRNA in the caudate-putamen and NAc core of wildtype mice and restored preprodynorphin mRNA levels in the nucleus accumbens core of Bdnf+/− mice. BDNF also restored the gene expression of preproenkephalin in the caudate-putamen of Bdnf+/− mice to wildtype levels; however, preproenkephalin mRNA in the nucleus accumbens did not differ among groups. Furthermore, BDNF increased D3 receptor mRNA in the nucleus accumbens core of wildtype and Bdnf+/− mice. These results demonstrate that exogenous BDNF restores striatal opioid and D3R gene expression in mice with genetically reduced levels of endogenous BDNF.

Keywords: brain-derived neurotrophic factor, caudate-putamen, dynorphin, enkephalin, dopamine D3 receptor, opioid peptides, nucleus accumbens

INTRODUCTION

Medium spiny neurons (MSNs) are a specific type of GABAergic projection neuron that comprise approximately 95% of the total population of neurons in the striatum. In the caudate-putamen (CPu), MSNs can be divided into two neurochemically distinct populations that characterize different striatal projection pathways (Gerfen and Young 1988). The striatonigral pathway projects from the striatum to the internal segment of the globus pallidus (rodent entopeduncular nucleus) and the substantia nigra; these neurons express D1 receptors and express the opioid peptide, dynorphin, and the tachykinin, substance P. In contrast, the striatopallidal pathway projects from the striatum to the external segment of the globus pallidus. The striatopallidal pathway expresses D2 receptors and the opioid peptide, enkephalin. In the nucleus accumbens (NAc), the expression of neuropeptides is less segregated than in the CPu; i.e., MSNs expressing dynorphin, enkephalin and substance P project to the ventral pallidum whereas MSNs expressing dynorphin and substance P project to the ventral tegmental area (Robertson and Jian 1995). Additionally, the dopamine D3 receptor (D3R) is expressed more abundantly in the NAc than in the CPu (Diaz et al. 2000). Like dopamine receptors in the CPu, the D3 receptor has been implicated in various neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, Parkinson’s disease, and drug addiction (Sokoloff et al. 2006). The expression of D3R, dynorphin, and enkephalin is tightly regulated by glutamate and dopamine and by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in cortical and mesencephalic projections to the striatum (Sauer et al. 1994; Wang et al. 1994; Arenas et al. 1996; Wang and McGinty 1996; Guillin et al. 2001; Saylor et al. 2006) and is also increased after acute cocaine, methamphetamine and morphine exposure (Le Foll et al. 2005; Simpson et al. 1995; Wang et al. 1994, 1995; Wang and McGinty 1996).

BDNF is a dynamic mediator of activity-dependent neuronal plasticity throughout the CNS (Turrigiano 2007; Bramham and Messaoudi 2005) and is required to maintain the normal phenotype and functioning of striatal MSNs (Sauer et al. 1994; Saylor et al. 2006). BDNF also facilitates the survival of MSNs after various types of insults, including hypoxia/ischemia (Galvin and Oorschot 2003), oxidative stress (Petersén et al. 2001) and in experimental models of Huntington’s disease (Canals et al. 2004; Perez-Navarro et al. 2000; Alberch et al. 2002; Baquet et al. 2004; Kells et al. 2004; Zuccato et al. 2005). Furthermore, BDNF is depleted in the striatum and/or in the cerebral cortex of Huntington’s disease patients (Gauthier et al. 2004; Zuccato et al. 2001).

Although striatal MSNs express a negligible amount of intrinsic Bdnf mRNA, the striatum receives extensive projections from glutamatergic afferents originating in cortex, hippocampus and amygdala, as well as mesencepahlic dopaminergic afferents that synthesize BDNF and transport the protein anterogradely (Altar et al. 1997; Altar and DiStefano 1998; Conner et al. 1997; Sauer et al. 1994). The biological effects of BDNF are primarily mediated by its protein tyrosine kinase receptor, TrkB (Ringstedt et al. 1993; Wong et al. 1997), which is abundantly expressed throughout the dorsal and ventral striatum in the postsynaptic density (PSD) of both dynorphin- and enkephalin-expressing populations of MSNs (Freeman et al. 2003, Guillin et al. 2001).

Preprodynorphin (PPD) and preproenkephalin (PPE) mRNA is substantially reduced in striatal MSNs of young Bdnf+/− mice and more global deficits in MSN gene expression, as well as the number of dendritic spines on MSNs, occur in aged Bdnf+/− mice (Saylor et al. 2006). Exogenous BDNF has been infused acutely, repeatedly, or continuously into the striatum or substantia nigra to investigate whether BDNF regulates striatal gene expression in intact or lesioned animals and in mutant mouse models (Arenas et al. 1996; Guillin et al. 2001; Sauer et al. 2004). Exogenous BDNF attenuated the decrease in the expression of D3 receptors, and preprotachykinin mRNA, but it had no effect on increased PPE mRNA, in 6-hydroxydopamine –treated rats (Guillin et al. 2001; Sauer et al. 2004). Further, continuous infusion of BDNF into the striatum for a week did not alter the number of DARPP-32-positive neurons, a marker of all MSNs, in bdnf+/− mice vs. wildtype mice (Canals et al. 2004). Taken together, these data indicate that BDNF differentially regulates gene expression in, and the integrity of, striatal MSNs. The present study was designed to determine whether infusion of exogenous BDNF into the striatum would restore the depressed striatal gene expression observed in mice with genetically reduced levels of endogenous BDNF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Bdnf+/− and wildtype mice were generated as described previously (Liebl et al. 1997) and subsequently backcrossed for 10–12 generations onto a C57/BL6 genetic background (Lyons et al.1999). Bdnf+/− mice carry a single null allele for BDNF and are viable, fertile, and have a normal life span, whereas mice homozygous for the mutant BDNF allele do not survive into adulthood. The mice used in this study were bred in HET x HET matings and genotyped locally at the Medical University of South Carolina as previously described (Saylor et al. 2006). Three month-old male littermates were group-housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures used on animals in this study were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Intrastriatal microinjections

Mice were anesthetized using a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg, i.p.; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA, USA) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.; Bayer, Shawnee Mission, KS, USA). While under anesthesia, mice were mounted onto a stereotaxic device (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA), and bilateral stainless steel guide cannulae (26 gauge, Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) were lowered to 2 mm above the striatal target region (AP +0.9mm, ML 2.0mm, DV −3.4mm, relative to bregma, Franklin & Paxinos 1999). Infusion cannulae (33 gauge; Plastics One) were inserted bilaterally into the guide cannulae such that 2 mm of the infusion cannulae extended past the end of the guide cannulae. Human recombinant BDNF (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or sterile 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was infused into mice (n=6 per group) using 10 μl Hamilton syringes and an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). BDNF (0.75 μg/μl PBS/side) was infused over 5 min and the infusion cannulae remained in the guide cannulae for 5 min before and after the infusion. This dose of BDNF has been used previously by our laboratory (Berglind et al. 2007; 2009) and others (Lu et al. 2004) in an in vivo single injection protocol in rats. Twenty-four hours after the infusion, mice were euthanized with an overdose of Equithesin (5 ml/kg, i.p.) and the whole brain was snap-frozen in isopentane at −35ºC in preparation for semi-quantitative in situ hybridization histochemistry.

Semi-quantitative in situ hybridization histochemistry

Semi-quantitative in situ hybridization histochemistry was performed as previously described (Gonzalez-Nicolini and McGinty 2002). Briefly, sections were cut at 12 μm with a cryostat through the striatum of each mouse and thaw-mounted onto Superfrost/Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The sections were pretreated to fix and defat the tissue and block non-specific hybridization. Synthetic cDNA oligodeoxynucleotide probes (48-mers) complementary to PPD (NCBI GenBank Accession number NM 019374, bases 839–886), PPE (NM 017139, bases 715–762), and D3R (NM 007877, bases 753–800) were radiolabeled with 35S-dATP (1250 Ci/mmol; New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) using terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Sections were immersed in 5.0×105 cpm/20 μl hybridization buffer/section overnight (~15h) at 37°C in a humid environment and then washed and air dried before being placed into a film cassette with 14C standards (American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) and Kodak Biomax film (Rochester, NY) for 4 days (PPE), 10 days (PPD), or 6 weeks (D3R).

Quantitation of the hybridization signals was performed using NIH image 1.62 (W. Rasband, NIMH) on a Macintosh G3 as previously described (Gonzalez-Nicolini and McGinty 2002). 14C standards were used to generate a calibration curve. Nonuniform illumination was corrected by saving a “blank field”. The upper limit of the density slice option was set to eliminate film background, and this value was used to measure all images. The lower limit was set at the bottom of the LUT scale. An appropriately sized oval field encompassing the centrolateral CPu or NAc core was used to measure hybridization signals from 3 sections per mouse (Figure 1). Changes were expressed as (1) the number of labeled pixels per unit area (area), (2) mean density of tissue in dpm/mg, and (3) integrated density (product of area x mean density). Integrated density more accurately depicts the area over which changes in optical density occur because mean density alone underestimates these changes (Wang and McGinty 1995; Zhou et al. 2004). The mean integrated density ± SEM in each mouse reflects the average values of three adjacent coronal sections; therefore, measurements of the hybridization signals were strongly correlated and could not be treated independently. For each gene, a mixed factor, nested repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted on the mean integrated density values with genotype and drug treatment as independent factors, followed by planned multiple comparison tests (Least Squares Means) when an interaction was found or to further analyze the source of main effects as previously described (Saylor et al. 2006).

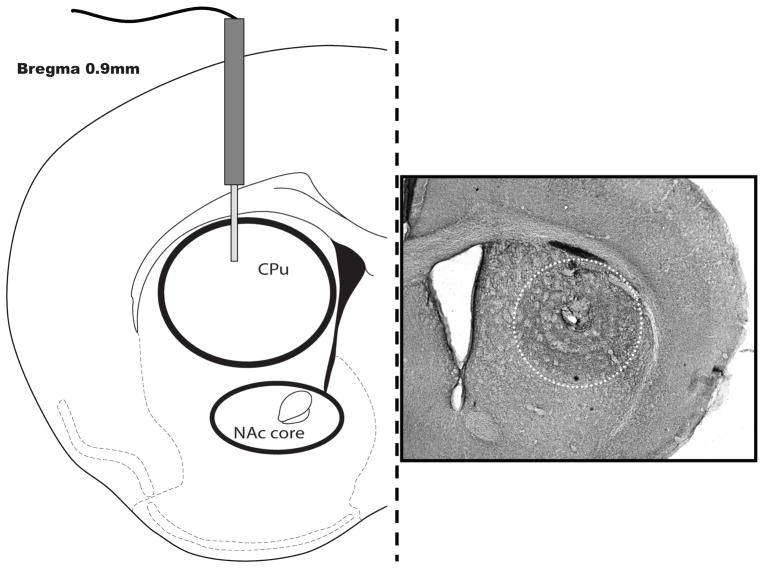

Figure 1.

Representative schematic (left panel) illustrating the location of the injector tip in the dorsal striatum and the approximate selection areas used in the image analysis of the hybridization signal. Immunocytochemistry for BDNF in a coronal hemisection illustrates the spread of diffusion throughout the striatum one hour after the microinjection (right panel).

Verification of BDNF infusion site by immunocytochemistry

One hour after BDNF microinfusion, a subset of mice (n=2) were transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde/10 mM PBS at 4°C. The brains were removed and postfixed in a 10% sucrose/4% paraformaldehyde solution for 2 h at 4°C, and then transferred to a 20% sucrose/PBS at 4°C to incubate overnight. Using a cryostat, 40 μm frozen sections were cut serially through the striatum and collected in PBS. Consecutive sections throughout the entire extent of the striatum were collected and incubated with primary antibody (rabbit anti-BDNF, 1:100, Santa Cruz) for 20 h at 4°C on a shaker. Sections were then incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antiserum (1:200, Vector Labs) for 1 h followed by avidin–biotin–peroxidase reagents (Elite Vectastain kit, Vector Labs) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then transferred to the VIP chromagen (Vector Labs) and allowed to develop for 1 min, at which time the sections were transferred to water for 5 min to stop the reaction. The sections were mounted out of PBS onto gelatin-coated slides and coverslipped in DPX.

RESULTS

Intrastriatal BDNF Infusion

Several commercial BDNF antisera were tested; however, all were low titer and yielded disappointing results for immunohistochemistry (data not shown). Coronal sections stained with the Santa Cruz BDNF antiserum showed enough immunoreactivity to demonstrate the spread of diffusion along with the location of the injector tip in the dorsal striatum one hour after the microinfusion (Figure 1). The center of the infusion was in the dorsocentral/dorsolateral CPu and the BDNF immunoreactivity was evenly spread around the tip of the cannula.

Gene expression

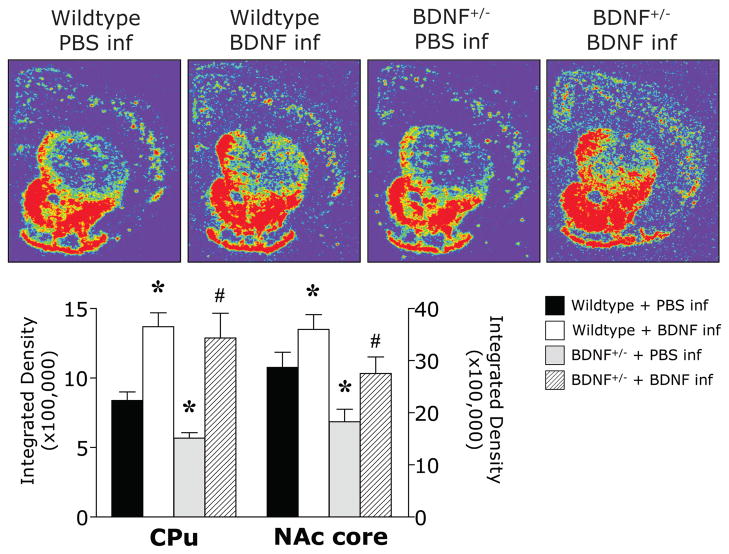

A characteristic pattern of PPD mRNA was detected in the CPu of wildtype mice infused with PBS in which high expression is confined to “patches” surrounded by low expression in the matrix whereas PPD mRNA in the NAc had a more abundant expression pattern that is particularly robust in the shell (Gerfen and Young 1988). Bdnf+/− mice expressed less PPD mRNA in the CPu than wildtype mice as previously reported in a different line of Bdnf+/− mice (Saylor et al. 2006) and intrastriatal BDNF infusion increased PPD gene expression in the CPu of both genotypes (Figure 2), Two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of genotype and drug treatment (F(1,17) = 42.98, p < .0001; F(1,17) = 3.39, p = .05) for PPD expression in the CPu. Similarly, significant main effects of genotype and drug treatment (F(1,17) = 12.64, p = .002; F(1,17) = 16.56, p = .0008) were observed for PPD expression in the NAc core. Planned comparison tests revealed that in the NAc core, Bdnf+/− mice expressed less PPD mRNA than wildtype mice. Intrastriatal BDNF infusion induced an increase of PPD mRNA in the NAc core of both wildtype and Bdnf+/− mice.

Figure 2.

Representative digitized pseudo-colored photomicrographs and image analysis illustrate the mRNA expression of PPD in the striatum of wildtype and BDNF+/− mice 24 hours after a single bilateral infusion of BDNF or PBS. *p<.05 vs WT + PBS infusion; #p<.05 vs BDNF+/− + PBS infusion. Brightness and contrast have been adjusted to provide optimal representation of the hybridization signal.

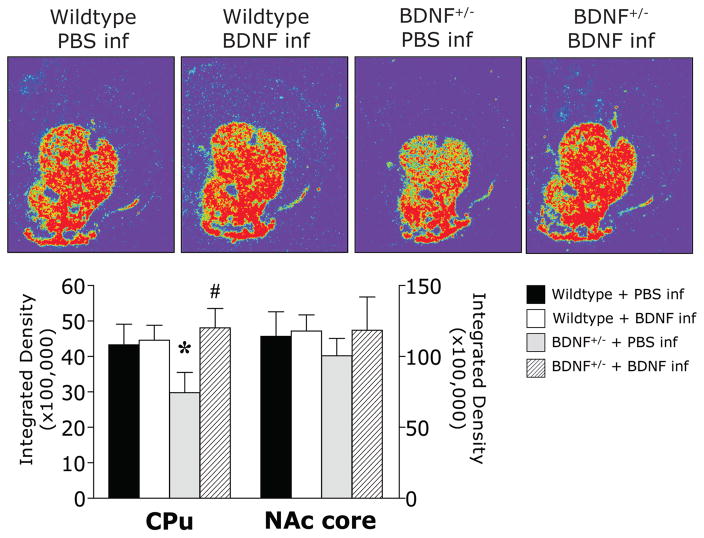

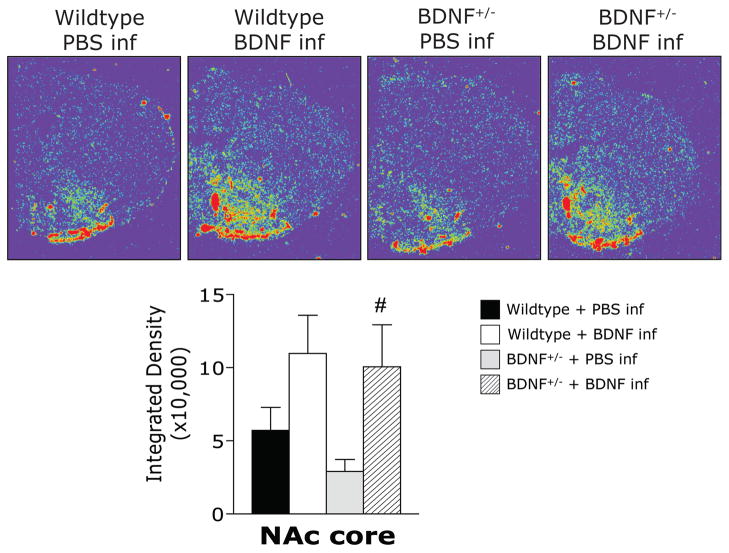

The photomicrographs in Figure 3 illustrate the characteristic expression pattern of PPE mRNA in control mice (WT+PBS) in which PPE mRNA was evenly and moderately expressed throughout the dorsal and ventral striatum (Gerfen and Young 1988). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant genotype by microinfusion interaction for PPE expression in the CPu (F(1,16) = 3.73, p = .05). Planned comparisons revealed that the baseline level of PPE mRNA was significantly lower in the CPu of Bdnf +/− mice than that of PBS-infused wildtype controls (Figure 3). In Bdnf+/− mice that received an intrastriatal infusion of BDNF, PPE expression was restored to wildtype levels; however, the BDNF infusion did not increase PPE mRNA in the CPu of wildtype mice. In the NAc core, no statistically significant differences in PPE mRNA levels were detected. The photomicrographs in Figure 4 illustrate the typical expression pattern of D3R mRNA in the striatum of control mice (WT+PBS) where D3R mRNA was largely confined to the ventral striatum, particularly robust in the olfactory tubercle (Diaz et al. 2000). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of microinfusion (F(1,16) = 10.48, p < .005) for D3R expression in the NAc core. At baseline, Bdnf+/− mice expressed approximately half the level of D3R mRNA in the NAc core as PBS-infused control wildtype mice, although this trend did not reach statistical significance (p = .08; Figure 4). Planned comparisons revealed that, compared to the appropriate PBS-infused control, an intrastriatal infusion of BDNF tended to increase D3R in the NAc core of Bdnf+/− mice, but this trend did not reach statistical significance in wildtype mice (p = .07).Since D3R mRNA is primarily contained within the ventral striatum, the CPu was not included in the analysis.

Figure 3.

Representative digitized photomicrographs and image analysis illustrate the mRNA expression of PPE in the striatum of wildtype and BDNF+/− mice 24 hours after a single bilateral infusion of BDNF or PBS. *p<.05 vs WT + PBS infusion, #p<.05 vs BDNF+/− + PBS infusion. Brightness and contrast have been adjusted to provide optimal representation of the hybridization signal.

Figure 4.

Representative digitized photomicrographs and image analysis illustrate the mRNA expression of D3R in the nucleus accumbens core of wildtype and BDNF+/− mice 24 hours after a single bilateral infusion of BDNF or PBS. #p< .05 vs BDNF+/− + PBS infusion. Brightness and contrast have been adjusted to provide optimal representation of the hybridization signal.

DISCUSSION

The present report indicates that exogenously supplied BDNF is able to restore abnormal striatal gene expression caused by a genetic reduction in endogenous BDNF levels. PPD, PPE and D3R mRNA were all decreased in the CPu and NAc core of Bdnf+/− mice versus wildtype controls. In Bdnf+/− mice, a single bilateral intrastriatal BDNF infusion was sufficient to rescue the reduced expression of PPD, PPE, and D3R. Intrastriatal infusion of BDNF restored the depressed expression of PPE mRNA in the CPu of Bdnf+/− mice to wildtype levels, but did not affect PPE expression in the CPu of wildtype mice or in the NAc core of either genotype. In contrast, an intrastriatal BDNF infusion altered the expression of PPD and D3R in a similar manner, by increasing expression of both genes in the striatum of wildtype and Bdnf+/− mice. These data suggest that BDNF is an important regulator of gene expression in striatal medium spiny neurons.

Multiple approaches to exogenous BDNF delivery have been previously reported; most of these studies have been conducted in rats and have employed a continuous, long-term, and/or high dose delivery of BDNF, usually via osmotic mini-pump administration for a week or more (Canals et al. 2004; Kernie et al. 2000; Berhow et al. 1996). A study by Xu and colleagues (2004) demonstrated that different patterns of BDNF infusion differentially affect the expression and phosphorylation state of TrkB. Continuous infusion over 14 days reduced the amount of full-length TrkB and decreased levels of phospho-Trks, compared to animals that received a bolus infusion of BDNF, in which there was no change in TrkB expression. Here we show in mice that a single, small, localized BDNF infusion is sufficient to compensate for a genetic deficit that has been present throughout the development of the animal. Further, this single infusion into the dorsal striatum increased PPD and D3R gene expression in both CPu and NAc core 24 hr later. We have demonstrated by immunocytochemistry (Figure 1) that microinfusion is an effective method by which to deliver BDNF and that the infused BDNF spread throughout the dorsal striatum. Although our gene expression studies were conducted in tissue processed 24 hours after the microinfusion, we illustrate the extent of the BDNF infusion at 1 hour because exogenous BDNF would have diffused away and been transported to other brain areas and therefore be unobservable at 24 hours. Since we observed gene expression changes in both CPu and NAc core at 24 hours after a local microinfusion into the dorsal striatum, it is likely either that infused BDNF spread beyond the region illustrated at 1 hour in Figure 1 to affect NAc gene expression 24 hr later or that BDNF had indirect, circuit-level effects on NAc gene expression after transport from the CPu to basal ganglia structures that innervate NAc like the substantia nigra.

There are two main populations of MSNs within the striatal complex: MSNs that express D1R and PPD and MSNs that express D2R and PPE. The D3R is primarily co-localized in those MSNs that express the D1R and PPD whereas PPE-containing MSNs do not express D3Rs (Curran and Watson 1995). Our data suggest that D1/D3R and PPD-expressing neurons in the striatum are more sensitive to BDNF regulation than D2/PPE-expressing MSNs. It is possible that the high level of PPE gene expression in indirect pathway neurons that is regulated by adenosine A2A and glutamate receptor stimulation requires the presence of TrkB receptors in the PSD for normal functioning, but cannot be further augmented by BDNF-TrkB stimulation in wildtype mice. However, when there is a BDNF-TrkB receptor signaling deficit as in Bdnf+/− mice, this high level of PPE gene expression is compromised, possibly by disrupting PSD signaling, that can be restored by BDNF infusion. In a transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease, intra-striatal infusion of BDNF via osmotic mini-pump for a week restored PPE, but not preprotachykinin mRNA levels, suggesting selectivity of BDNF for the most vulnerable MSN population in Huntington’s disease patients (Canals et al. 2004).

The expression profiles of PPD and D3R changed similarly, and in a different and more dynamic manner than PPE expression, particularly in the NAc core, after an intrastriatal BDNF infusion. In wildtype mice, intrastriatal BDNF infusion elevated PPD and D3R gene expression above the levels observed in PBS-infused wildtype mice. Interestingly, intrastriatal BDNF infusion administered to Bdnf+/− mice induced a larger increase in PPD and D3R mRNA expression than the increase observed in wildtype mice. That is, relative to PBS-infused controls of the same genotype, Bdnf+/− mice showed a much greater percent increase in gene expression compared to wildtype mice that also received a BDNF infusion. For example, PPD mRNA was increased by 127% in the CPu of Bdnf+/− mice that received a BDNF infusion, versus a 63% BDNF-induced increase observed in wildtype mice. Similarly, D3R mRNA was increased by 247% in the NAc core of Bdnf+/− mice that received a BDNF infusion, versus a 92% BDNF-induced increase observed in wildtype mice. It is possible that the augmented response to exogenous BDNF observed in Bdnf+/− mice was due to a compensatory increase in TrkB receptors in a system with genetically reduced levels of BDNF. When the availability of BDNF was increased via the microinfusion, enhanced signaling via TrkB receptors on D3R- and PPD-expressing neurons could result in augmented gene expression exceeding that of wildtype mice. Indeed, the fact that PPE mRNA was not altered by BDNF infusion in wildtype mice but was increased in Bdnf+/− mice is also consistent with this interpretation (see above). Further studies are required to determine whether alterations in TrkB receptors are indeed responsible for the amplified increase in BDNF-induced gene expression in Bdnf+/− mice.

More than 70% of neurons in the NAc co-express mRNA for both TrkB and D3 receptors (Guillin et al. 2001). BDNF is required for normal expression of D3R in the NAc during development, but does not affect expression of either D1 or D2 receptors (Guillin et al. 2001). BDNF from both cortical and ventral tegmental afferents directly regulates D3R expression in the NAc in adulthood; the typical levodopa-induced increase of D3R expression and behavioral sensitization to repeated levodopa treatments was prevented in rats that were either decorticated or dopamine-depleted (Guillin et al. 2001). Further, a single injection of cocaine, methamphetamine or morphine induces a transient increase of Bdnf mRNA in the prefrontal cortex that is followed by a long-lasting elevation of D3R expression in the NAc (Le Foll et al. 2005). The results from the present study indicate that D3R mRNA tends to be reduced in adult Bdnf+/− mice and can be rescued by a single infusion of BDNF. In our hands, Bdnf+/− mice display abnormal amphetamine-induced locomotor activity and striatal D3R gene expression (Saylor and McGinty 2008). Further study is needed to determine whether alterations in D3R expression contribute to the abnormal responses to psychostimulant administration in Bdnf+/− mice.

BDNF is co-transported with glutamate and dopamine and is released by both cortical and mesencephalic afferents. However, it is estimated that approximately 95% of total striatal BDNF protein is delivered by cortical projections (Baquet et al. 2004), with a less significant input from other afferents. The present results indicate that exogenous BDNF restores the integrity of medium spiny neurons by increasing opioid and D3R gene expression in mice with genetically reduced levels of endogenous BDNF. Since the opioid peptides and the D3R modulate local neurotransmission within the striatum and thereby contribute to the regulation of overall striatal output, corticostriatal BDNF is in a position to fundamentally influence neuronal activity and function within the basal ganglia circuitry.

Acknowledgments

Funded by NIH PO1 AG023630, RO1 DA03982, F31 DA020238 (AJS), and CO6 RR015455

LITERATURE CITED

- Alberch J, Pérez-Navarro E, Canals JM. Neuroprotection by neurotrophins and GDNF family members in the excitotoxic model of Huntington’s disease. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:817–22. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, Cai N, Bliven T, Juhasz M, Conner JM, Acheson AL, Lindsay RM, Wiegand SJ. Anterograde transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its role in the brain. Nature. 1997;389:856–860. doi: 10.1038/39885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, DiStefano PS. Neurotrophin trafficking by anterograde transport. Trends Neurosciences. 1998;21:433–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas E, Akerud P, Wong V, Boylan C, Persson H, Lindsay RM, Altar CA. Effects of BDNF and NT-4/5 on striatonigral neuropeptides or nigral GABA neurons in vivo. Eur J Neuroscience. 1996;8:1707–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquet ZC, Gorski JA, Jones KR. Early striatal dendrite deficits followed by neuron loss with advanced age in the absence of anterograde cortical brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neuroscience. 2004;24:4250–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3920-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, See RE, Fuchs RA, Ghee SM, Whitfield TW, Jr, Miller SW, McGinty JF. A BDNF infusion into the medial prefrontal cortex suppresses cocaine seeking in rats. Eur J Neuroscience. 2007;26:757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, Whitfield TW, Jr, Lalumiere RT, Kalivas PW, McGinty JF. A Single Intra-PFC infusion of BDNF prevents cocaine-induced alterations in extracellular glutamate within the nucleus accumbens. J Neuroscience. 2009;29:3715–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5457-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhow MT, Hiroi N, Nestler EJ. Regulation of ERK (extracellular signal regulated kinase), part of the neurotrophin signal transduction cascade, in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system by chronic exposure to morphine or cocaine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4707–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04707.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR, Messaoudi E. BDNF function in adult synaptic plasticity: the synaptic consolidation hypothesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:99–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals JM, Pineda JR, Torres-Peraza JF, Bosch M, Martín-Ibañez R, Muñoz MT, Mengod G, Ernfors P, Alberch J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates the onset and severity of motor dysfunction associated with enkephalinergic neuronal degeneration in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7727–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1197-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner JM, Lauterborn JC, Yan Q, Gall CM, Varon S. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. J Neuroscience. 1997;17:2295–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran E, Watson SJ., Jr Dopamine receptor mRNA expression patterns by opioid peptide cells in the nucleus accumbens of the rat: A double in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:57–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz J, Pilon C, Le Foll B, Gros C, Triller A, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Dopamine D3 receptors expressed by all mesencephalic dopamine neurons. J Neuroscience. 2000;20:8677–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08677.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KB, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman AY, Soghomonian JJ, Pierce RC. Tyrosine kinase B and C receptors in the neostriatum and nucleus accumbens are co-localized in enkephalin-positive and enkephalin-negative neuronal profiles and their expression is influenced by cocaine. Neuroscience. 2003;117:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin KA, Oorschot DE. Continuous low-dose treatment with brain-derived neurotrophic factor or neurotrophin-3 protects striatal medium spiny neurons from mild neonatal hypoxia/ischemia: a stereological study. Neuroscience. 2003;118:1023–32. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier LR, Charrin BC, Borrell-Pagès M, Dompierre JP, Rangone H, Cordelières FP, De Mey J, MacDonald ME, Lessmann V, Humbert S, Saudou F. Huntingtin controls neurotrophic support and survival of neurons by enhancing BDNF vesicular transport along microtubules. Cell. 2004;118:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Young WS. Distribution of striatonigral and striatopallidal peptidergic neurons in both patch and matrix compartments: an in situ hybridization histochemistry and fluorescent retrograde tracing study. Brain Res. 1988;460:161–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoussi Z, Leontiadis L, Mazarakou G, Merkouris M, Hyde K, Hamm H. Selective interactions between G protein subunits and RGS4 with the C-terminal domains of the mu- and delta-opioid receptors regulate opioid receptor signaling. Cell Signal. 2006;18:771–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Nicolini V, McGinty JF. Gene expression profile from the striatum of amphetamine-treated rats: a cDNA array and in situ hybridization histochemical study. Brain Res Gene Expr Patterns. 2002;1:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillin O, Diaz J, Carroll P, Griffon N, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. BDNF controls dopamine D3 receptor expression and triggers behavioural sensitization. Nature. 2001;411:86–9. doi: 10.1038/35075076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovic S, Polonskaia O, Farinas I, Ehrlich ME. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates maturation of the DARPP-32 phenotype in striatal medium spiny neurons. Neuroscience. 1997;79:509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kells AP, Fong DM, Dragunow M, During MJ, Young D, Connor B. AAV-mediated gene delivery of BDNF or GDNF is neuroprotective in a model of Huntington disease. Mol Ther. 2004;9:682–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernie SG, Liebl DJ, Parada LF. BDNF regulates eating behavior and locomotor activity in mice. Embo J. 2000;19:1290–1300. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Diaz J, Sokoloff P. A single cocaine exposure increases BDNF and D3 receptor expression: implications for drug-conditioning. NeuroReport. 2005;16:175–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502080-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Francès H, Diaz J, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Role of the dopamine D3 receptor in reactivity to cocaine-associated cues in mice. Eur J Neuroscience. 2002;15:2016–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebl DJ, Tessarollo L, Palko ME, Parada LF. Absence of sensory neurons before target innervation in brain-derived neurotrophic factor-, neurotrophin 3-, and TrkC-deficient embryonic mice. J Neuroscience. 1997;17:9113–9121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09113.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B. BDNF and activity-dependent synaptic modulation. Learn Mem. 2003;10:86–98. doi: 10.1101/lm.54603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Navarro E, Canudas AM, Akerund P, Alberch J, Arenas E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin-3, and neurotrophin-4/5 prevent the death of striatal projection neurons in a rodent model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2190–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersén A, Larsen KE, Behr GG, Romero N, Przedborski S, Brundin P, Sulzer D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits apoptosis and dopamine-induced free radical production in striatal neurons but does not prevent cell death. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;56:331–335. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringstedt T, Lagercrantz H, Persson H. Expression of members of the trk family in the developing postnatal rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;72:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson GS, Jian M. D1 and D2 dopamine receptors differentially increase Fos-like immunoreactivity in accumbal projections to the ventral pallidum and midbrain. Neuroscience. 1995;64:1019–34. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer H, Campbell K, Wiegand SJ, Lindsay RM, Bjorklund A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances striatal neuropeptide expression in both the intact and the dopamine-depleted rat striatum. NeuroReport. 1994;5:609–612. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199401000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor AJ, McGinty JF. Amphetamine-induced locomotion and gene expression are altered in BDNF heterozygous mice. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2008;7:906–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor AJ, Meredith GE, Vercillo MS, Zahm DS, McGinty JF. BDNF heterozygous mice demonstrate age-related changes in striatal and nigral gene expression. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:362–72. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JN, McGinty JF. Forskolin induces preproenkephalin and preprodynorphin mRNA in rat striatum as demonstrated by in situ hybridization histochemistry. Neuroscience. 1995;69:441–57. doi: 10.1002/syn.890190302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Giros B, Martres MP, Bouthenet ML, Schwartz JC. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dopamine receptor (D3) as a target for neuroleptics. Nature. 1990;347:146–51. doi: 10.1038/347146a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Diaz J, Le Foll B, Guillin O, Leriche L, Bezard E, Gross C. The dopamine D3 receptor: a therapeutic target for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;5:25–43. doi: 10.2174/187152706784111551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand AD, Baquet ZC, Aragaki AK, Peter Holmans P, Yang L, Cleren C, Beal MF, Jones L, Kooperberg C, Olson JM, Jones KR. Expression profiling of Huntington’s disease models suggests that brain-derived neurotrophic factor depletion plays a major role in striatal degeneration. J Neuroscience. 2007;27:11758–11768. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2461-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Daunais JB, McGinty JF. NMDA receptors mediate amphetamine-induced upregulation of zif/268 and preprodynorphin mRNA expression in rat striatum. Synapse. 1994;18:43–353. doi: 10.1002/syn.890180410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Smith AWS, McGinty JF. A single injection of amphetamine or methamphetamine induces dynamic alterations in c-fos, zif/268 and preprodynorphin mRNA expression in rat forebrain. Neuroscience. 1995;68:83–95. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00100-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, McGinty JF. D1 and D2 receptor regulation of preproenkephalin and preprodynorphin mRNA in rat striatum following acute injection of amphetamine or methamphetamine. Synapse. 1996;22:114–122. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199602)22:2<114::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JY, Liberatore GT, Donnan GA, Howells DW. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and TrkB neurotrophin receptors after striatal injury in the mouse. Exp Neurol. 1997;148:83–91. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Michalski B, Racine RJ, Fahnestock M. The effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) administration on kindling induction, Trk expression and seizure-related morphological changes. Neuroscience. 2004;126:521–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Mailloux AW, Jung BJ, Edmunds HS, McGinty JF. GABAB receptor stimulation decreases amphetamine-induced behavior and neuropeptide gene expression in the striatum. Brain Res. 2004;1004:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C, Ciammola A, Rigamonti D, Leavitt BR, Goffredo D, Conti L, MacDonald ME, Friedlander RM, Silani V, Hayden MR, Timmusk T, Sipione S, Catteneo E. Loss of huntingtin-mediated BDNF gene transcription in Huntington’s disease. Science. 2001;293:493–498. doi: 10.1126/science.1059581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato C, Liber D, Ramos C, Tarditi A, Rigamonti D, Tartari M, Valenza M, Cattaneo E. Progressive loss of BDNF in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease and rescue by BDNF delivery. Pharmacol Res. 2005;52:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]