Abstract

During spatial exploration, hippocampal neurons show a sequential firing pattern in which individual neurons fire specifically at particular locations along the animal’s trajectory (place cells1,2). According to the dominant model of hippocampal cell assembly activity, place cell firing order is established for the first time during exploration, to encode the spatial experience, and is subsequently replayed during rest3–6 or slow-wave sleep7–10 for consolidation of the encoded experience11,12. Here we report that temporal sequences of firing of place cells expressed during a novel spatial experience occurred on a significant number of occasions during the resting or sleeping period preceding the experience. This phenomenon, which is called preplay, occurred in disjunction with sequences of replay of a familiar experience. These results suggest that internal neuronal dynamics during resting or sleep organize hippocampal cellular assemblies13–15 into temporal sequences that contribute to the encoding of a related novel experience occurring in the future.

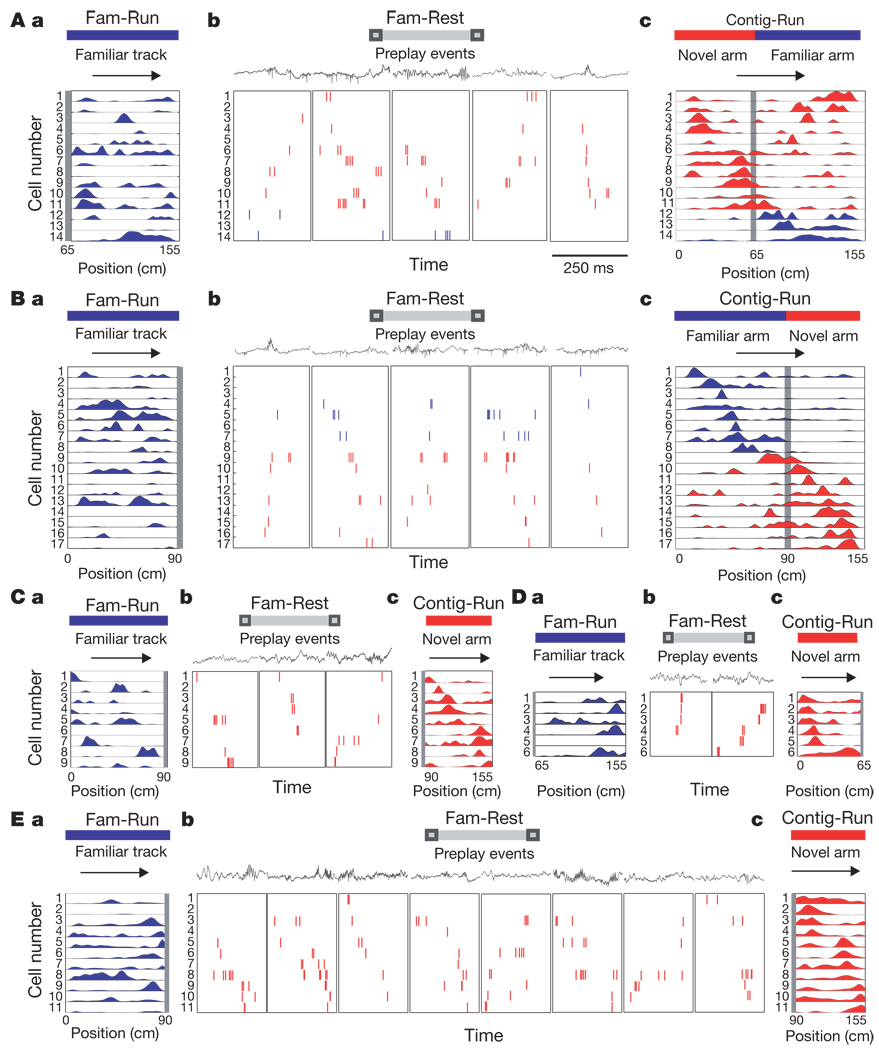

We recorded neuronal firing sequences from the CA1 area of the mouse hippocampus (Supplementary Fig. 1) during periods of awake rest (Fam-Rest) alternating with periods of running (Fam-Run) on a familiar track (Fam session; Supplementary Fig. 2a) that preceded the exploration of a novel linear arm in contiguity with the familiar track (Contig-Run on L-shaped track; Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2a and Methods). All the place cells active on the novel arm during Contig-Run, whether previously silent16 (19% in both directions and 31% in at least one direction; Methods and Supplementary Tables 1–3) or active during Fam-Run (subpanels a in Fig. 1), fired during Fam-Rest at the ends of the familiar track (range, 0.17–11.7 Hz; Supplementary Fig. 3) as part of a number of ‘spiking events’. The spiking events were defined as epochs composed of multiple individual spikes from at least four different place cells active on the novel arm or familiar track, separated by less than 50 ms and flanked by at least 50 ms of silence3,4. More significantly, the temporal sequence in which the cells active on the novel arm fired during Fam-Rest (subpanels b in Fig. 1) was significantly correlated with the spatial sequence in which they fired later as place cells on the novel arm during Contig-Run (subpanels c in Fig. 1), despite being uncorrelated with their spatial sequence as place cells on the familiar track during Fam-Run. This is illustrated as place cell sequences during Contig-Run (subpanels c in Fig. 1) and Fam-Run (subpanels a in Fig. 1) compared with the firing sequences of these cells within individual spiking events observed during Fam-Rest (subpanels b in Fig. 1). We refer to this process as ‘preplay’ of place cell sequences because the temporal sequence of firing during Fam-Rest had occurred before the actual exploration of the novel arm in the subsequent Contig-Run and was not a replay of the place cell sequences from the previous Fam-Run.

Figure 1. Preplay of novel place cell sequences.

Fam-Run and Fam-Rest respectively denote run and rest sessions on the familiar linear track before barrier removal; Contig-Run denotes run sessions on the L-shaped track after barrier removal. The L-shape track was linearized for display/analysis. A, B, mouse 1;C,D, mouse 2; E, mouse 3.A–E, a, Spatial activity on the familiar track during Fam-Run of the cells that had place fields in Contig-Run and preplayed during Fam-Rest (one cell per row); activity on the novel arm and familiar track are on the same scale. Horizontal arrows indicate run directions. Vertical grey bars indicate barrier locations during Fam-Run and Fam-Rest. A–E, b, Examples of representative spiking events in the forward or reverse direction during Fam-Rest in 250-ms time windows (350 ms for the second and fourth panels from left in E, b). Tick marks indicate individual spikes: red, preplay events for place cell sequences in the novel arm; blue (in A, b and B, b), additional spikes from the familiar track place cells participating in the spiking event (not shown in C–E, b). Numbers on the left denote cell numbers and correspond to the place cell numbers in A–E, a. Square boxes indicate the ends of the familiar track where preplay events occurred. Local field potentials recorded simultaneously with the spikes are shown above spiking events. A–E, c, Place cell sequences in the novel arm (C–E, c; red) or in both the novel arm (red) and the familiar arm (blue) (A, c and B, c) in Contig-Run.

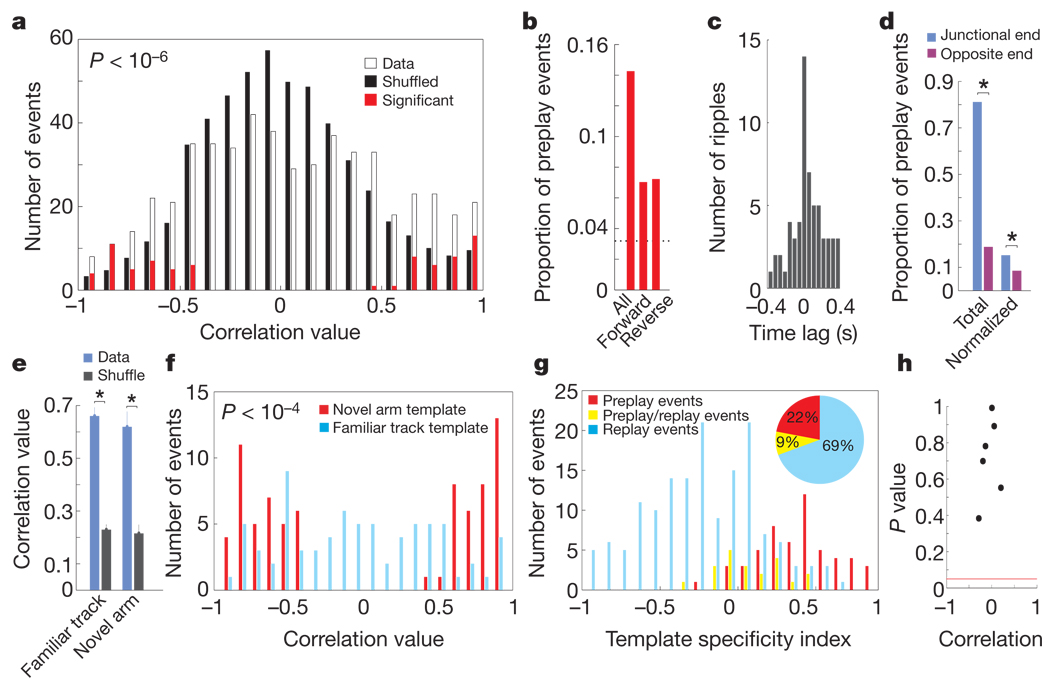

To quantify the significance of preplay and to compare it with replay, we created place cell sequence templates according to the spatial order of the peak firing of place cells3,4,10 on the novel arm during Contig-Run (novel arm templates; subpanels c in Fig. 1 and Methods) and on the familiar track during Fam-Run (familiar track templates) for each run direction. The spikes of all the place cells used to construct the two types of template that were emitted during Fam-Rest were sorted by time, and spiking events were determined as explained above (subpanels b in Fig. 1). For each spiking event, we calculated a rank-order correlation between the novel armtemplates and the temporal sequence of firing of the corresponding cells in the spiking events during Fam-Rest. The event correlation was considered significant if it exceeded the 97.5th percentile of a distribution of correlations resulting from randomly shuffling the order of place cells in the novel arm templates 200 times (P < 0.025). Forward4 and reverse3,4 preplay refers to the cases in which the sequence of place cells during Contig-Run and the firing order of the corresponding cells in Fam-Rest were in the same and opposite directions, respectively. In 91% of the preplay cases, the spiking events were correlated with the novel armtemplate in one direction only. The distribution of event correlation values obtained using the original novel arm templates was significantly shifted towards higher positive or negative values in comparison with the distribution of correlation values obtained using shuffled templates (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4). Figure 2a also shows the distribution of significant preplay events (in red). Of all the spiking events detected as above and in which at least four novel arm place cells were active, 14.2% were significant preplay events for the place cell sequence on the novel arm(P < 10−32, binomial probability test4) in the forward or reverse order (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Quantification of the preplay phenomenon and comparison with replay.

a, Distribution of correlations between spiking events in Fam-Rest and spatial templates of the novel arm. Open bars indicate spiking events versus the original (unshuffled) templates; filled bars indicate spiking events versus 200 shuffled templates scaled down 200 times; red bars show the distribution of preplay (that is, significant) events. Similar distributions (not shown) of corresponding spiking events were obtained when spatial templates were constructed using all place cells active on the L-shaped track (Figs 1A, b, c and 1B, b, c; red and blue). b, Proportion of all, forward and reverse preplay events among the spiking events in Fam-Rest. The dotted line indicates the chance level (3.2%). c, Cross-correlation between preplay events and ripple epochs. d, Location of preplay events on the familiar track: total, proportions of preplay events at ends of the track; normalized, proportion of preplay events normalized by the number of spiking events at each end of track. Preplay events represented a trajectory running from the free end of the novel arm to the junctional end (40%) or begun near the familiar track (60%); the latter suggests that in some cases preplay events could be triggered by the activity of the familiar track place cells during Fam-Rest. e, Stability of place cell spatial tuning across the novel experience: familiar track, stability of the place fields active on the familiar track before (Fam-Run) versus after (Contig-Run) barrier removal; novel arm, stability of the place fields active on the novel arm at the beginning (first four laps of run) versus the end (last four laps) of the Contig-Run session. Data (blue), within-cell correlation of place cell spatial tuning for the corresponding track/arm; shuffle (black), cell identity shuffle (Supplementary Information). Error bars, s.e.m.; asterisks in d and e indicate significant differences. f, Distribution of preplay event correlations (red) versus distribution of these event correlations with the familiar track template (blue). Spiking events were detected using all place cells from the familiar track and novel arm templates (>1 Hz). Red bars are the same as in a. Correlation is strong with the novel arm template (preplay) and weak with the familiar arm template (replay). The P value corresponds to there being a significant difference between the two distributions. g, Disjunctive distribution of pure preplay (red), pure replay (blue) and preplay/replay (yellow) events during Fam-Rest over their template specificity index (Supplementary Information). Inset, proportions of pure preplay events (red), pure replay events (blue) and preplay/replay events (yellow) among all of the spiking events that were significantly correlated with at least familiar track templates or novel arm templates. h, Lack of correlation between the novel arm template and the corresponding familiar track template. Each of the six dots represents either a forward or a reverse run direction of one of the three mice analysed. Red horizontal line denotes a P value of 0.05. The correlation values were not significant in any of the cases (Supplementary Information).

The occurrence of significant preplay events was correlated with the occurrence of high-frequency ripple oscillations in CA1 (Fig. 2c). The majority of the significant preplay events (81.1%; Fig. 2d, total, blue) took place at the junction between the familiar and novel arms, and the remaining 18.9% took place at the free end of the familiar track (Fig. 2d, total, purple). The proportion of significant preplay events among the total events at each of the two track ends was higher at the junctional end (15.2%, P < 10−26) than at the free end (8.5%, P < 10−4) of the familiar track (P < 0.035, Z-test; Fig. 2d, normalized).

We found a relatively high correlation between the place field maps (Fig. 1A, B and Supplementary Fig. 5) of the familiar track before and after the novel experience (median r = 0.66; Fig. 2e, familiar track, blue); it was significantly higher than the correlations obtained when the cell identities were shuffled (median r = 0.23, P < 10−4; Fig. 2e, familiar track, black).A similar correlation analysis showed a relatively high stability of the newly formed place fields on the novel arm from the beginning to the end of Contig-Run (median r = 0.62 (newly formed) versus median r = 0.21 (shuffled), P < 10−3; Fig. 2e, novel arm, blue versus grey). These results suggest that preplay of the novel arm does not occur over an entirely new (that is, remapped) representation of the whole L-shaped track but rather benefits from the relative stability of the familiar track representation across sessions and perhaps facilitates the rapid, stable encoding of the novel arm experience.

Using the familiar track templates and spiking events during Fam-Rest, constructed as above, we determined that 16.2% (P < 10−91; data not shown) were significant replay events3–6,17 among the spiking events in which a minimum of four familiar track place cells were active. All significant preplay events occurring during Fam-Rest (n = 75) were tested for possible replay of the familiar track spatial sequence: these spiking events were more correlated with the novel arm template (Fig. 2f, red) than the familiar track template (Fig. 2f, blue). Seventy-two percent (n = 54) of the significant events previously considered to be preplay had no significant correlation with the familiar track template. An additional 16% (n = 12) of those events were better correlated with the novel arm templates (mean absolute r = 0.92) than with the familiar track template (mean absolute r = 0.67, P < 10−3). Together, these findings reject the hypothesis that the preplay events simply represent a replay of the familiar track activity (see additional controls in Supplementary Information). Moreover, we found that the proportion of events exclusively composed of silent cells that perfectly matched the novel arm spatial templates was 0.67 (16 of 24 triplets), which is significantly greater (P < 0.025) than the proportion of by-chance perfect matches (0.33).

To illustrate the distribution and relative proportions of preplay and replay events among all significant spiking events during Fam-Rest, we calculated a ‘template specificity index’ (Fig. 2g and Methods) for each event. Pure preplay events (Fig. 2g, red) and pure replay events (Fig. 2g, blue) were segregated, and only a minority of events were significant for both preplay and replay (Fig. 2g, yellow). Consistent with this segregation of preplay and replay events, the novel arm and the ‘corresponding familiar track’ templates were not significantly correlated (Fig. 2h and Methods). The ratio between the number of pure replay events (n = 171) and the number of pure preplay events (n = 54) during Fam-Rest was about 3.1 (Fig. 2g, inset; see Supplementary Information for proportions of events). Preplay and replay events were distributed in time across Fam-Rest (Supplementary Fig. 6a–c) and their occurrences were generally uncorrelated (Supplementary Fig. 6d). The majority (79.9%) of the spiking events during Fam-Rest did not significantly correlate with either of the two templates (data not shown).

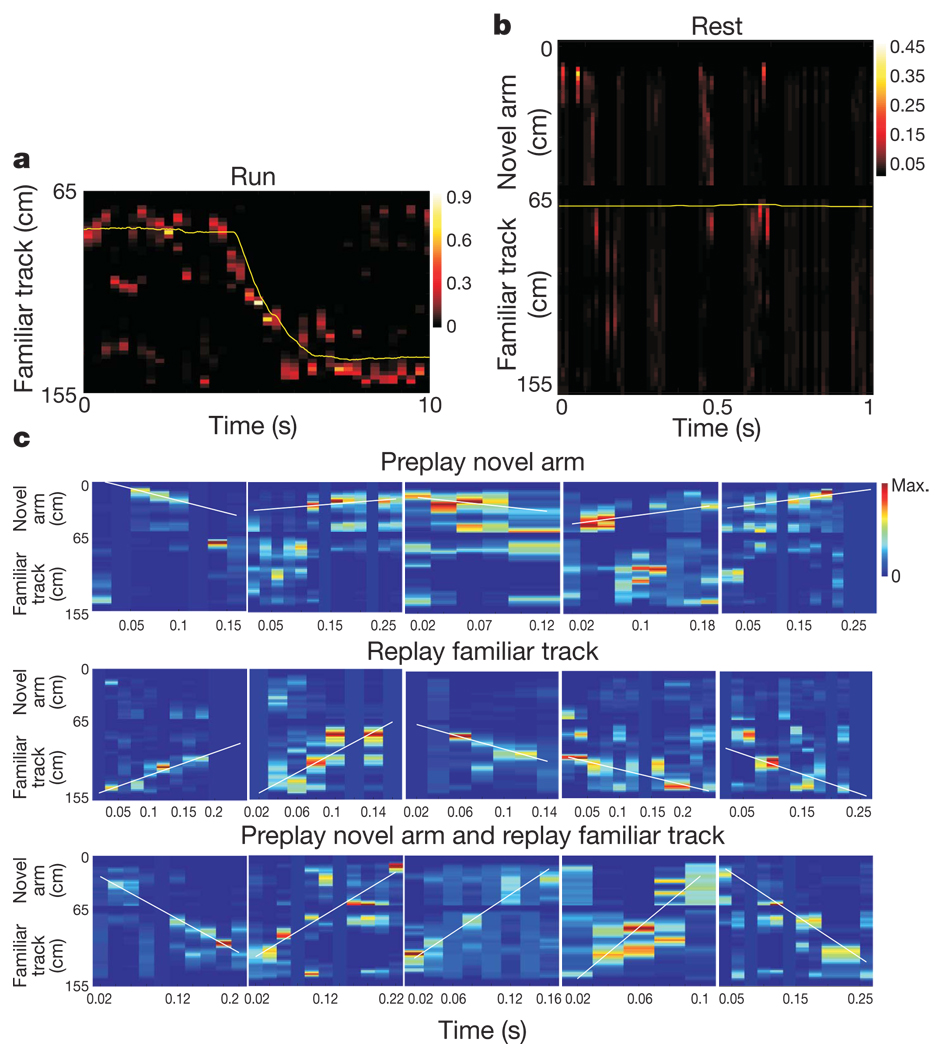

We used a Bayesian reconstruction algorithm2,5,6,18,19 (Methods) to decode the animals’ position from the spiking activity during Fam-Run (Fig. 3a) or Fam-Rest (Fig. 3b, c). For all original and shuffled6 probability distributions, a line was fitted to the data using a line-finding algorithm6 to represent the decoded virtual trajectory (Methods and Supplementary Information). In 16.36% of cases representing trajectories, the reconstructed trajectory during spiking events in Fam-Rest was contained within the novel arm (Fig. 3c, top), a place the animal had not yet visited (that is, trajectory preplay). Moreover, in 79.8% of the trajectory preplay cases the shuffling procedures resulted in lines that were significantly less or not at all contained within the novel arm (that is, not preplay; Supplementary Information). The remaining trajectories decoded during Fam-Rest represented replay of the familiar track (64.15%; Fig. 3c, middle) or spanned the joint familiar track/novel arm space (19.49%; Fig. 3c, bottom). Means of absolute rank-order correlations between spiking activity and novel arm templates (Fig. 2a) restricted during epochs of trajectory preplay were significantly larger than those between spiking activity and familiar track templates calculated during the same epochs (0.75 versus 0.59, P < 10−4). Overall, these results support the existence of the preplay phenomenon.

Figure 3. Bayesian reconstruction of the animal’s trajectory in the familiar track (replay) and novel arm (preplay).

a, Position reconstruction of a one-lap run on the familiar track fromthe ensemble place cell activity during Fam-Run. The heat map displays the reconstructed position of the animal using ensemble place cell activity during the run (250-ms bins; animal velocity, >5 cm s−1). The yellow line indicates the actual trajectory of the animal during Fam-Run. b, Example of virtual trajectory reconstruction (familiar track and novel arm) from the ensemble place cell activity during Fam-Rest at the ends of the familiar track (20-ms bins; animal velocity, <5 cm s−1) before barrier removal and novel arm exploration. The yellow line reflects the spatial location of the animal in time: the animal was immobile at the junction end of the familiar track. The time-compressed (~5 m s−1) trajectory reconstruction often ‘jumps’ over the barrier (top of the figure) into the novel arm area. At around 0.5 s, a preplay of the novel arm initiated from the distal (free) end of the novel arm ‘propagates’ towards the location of the animal. c, Examples of preplay of the novel arm (top), replay of the familiar track (middle) and preplay of the novel arm together with replay of the familiar track (bottom) during Fam-Rest. All conditions are the same as in b. The white line shows the linear fit maximizing the likelihood along the virtual trajectory. Colour bars indicate probability of trajectory reconstruction.

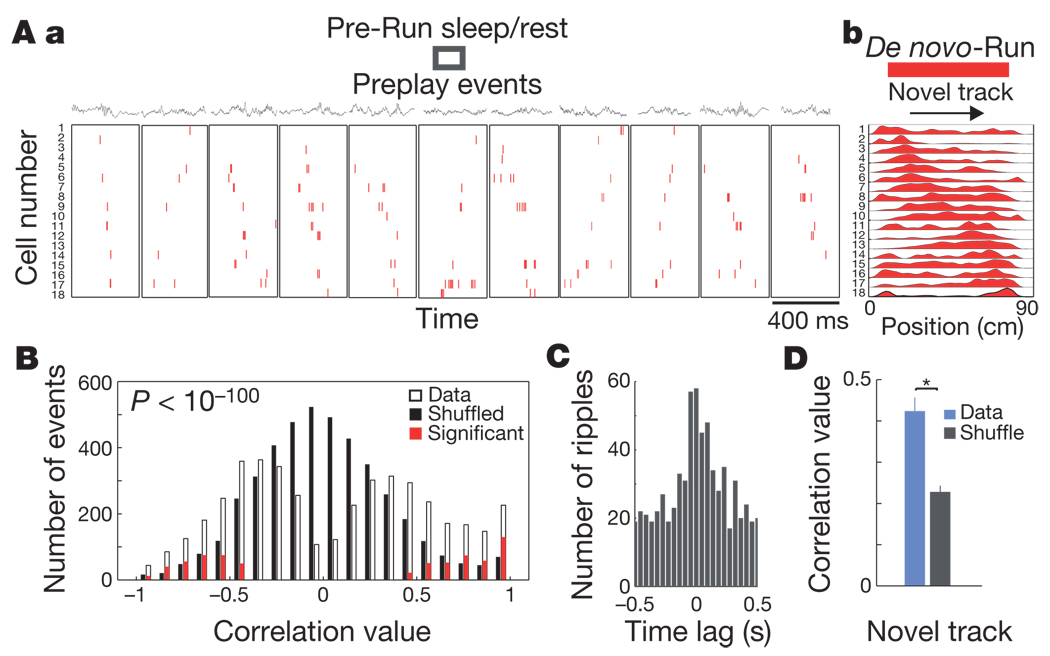

To investigate the possibility that preplay of novel arm place cell sequences during Fam-Rest depends on the prior run experience on the familiar track, mice with no prior experience on any linear track were placed in a high-walled sleep box and recorded while resting/sleeping. The animals were then transferred to a novel isolated linear track that was in the same room but could not be seen from inside the box, and the recording continued during de novo formation of place cells (Supplementary Fig. 2b, de novo session). We found that in a relatively large proportion (16.1%) of spiking events identified during sleep/rest in the sleep box, the neuronal firing sequences were significantly correlated with the place cell sequences observed during the first run session on the novel track (Fig. 4A, B and Methods); this was the case for all four individual mice (Supplementary Fig. 7). Preplay events were associated with the ripple occurrence (Fig. 4C). The place cells established on the novel track in the de novo session were more dynamic (median r = 0.42; Fig. 4D, blue) than in Contig-Run (median r = 0.62, P < 0.016; Fig. 2e, right, blue).

Figure 4. Preplay of novel place cell sequences before any linear track experience.

A, Sleep/rest session in the sleep box (Pre-Run sleep/rest) before the first run session on a linear track (De novo-Run). Display format is the same as in Fig. 1. A, a, Representative spiking events in the forward or reverse order during Pre-Run sleep/rest in 400-ms time windows. A, b, Place cell sequences on the novel track (red) during the De novo-Run session. Each row represents one cell in which the activity was normalized to the maximum firing rate. One run direction in one animal is shown. The median number of place cells active on the novel track participating in preplay events is six. B, Distribution of spiking events in Pre-Run sleep/rest as a function of the rank-order correlation with the place cell sequence template of the novel track. Display format is the same as in Fig. 2a. C, Cross-correlation between preplay events and ripple epochs during Pre-Run sleep/rest.D, Stability of place cell spatial tuning across the novel track experience. Display format is the same as in Fig. 2e (novel arm). Error bars, s.e.m.; asterisk indicates significant difference.

We have demonstrated that a significant number of temporal firing sequences of CA1 cells during resting periods of a familiar track exploration that preceded a novel track exploration in the same general environment were correlated with the place cell sequences of the novel track rather than the familiar track. This phenomenon, preplay, is temporally opposite to the process of replay3–10,19,20, when activity during rest or sleep periods recapitulates place cell sequences that have already occurred during previous explorations. Preplay differs fundamentally from replay because it occurs before exploration of novel tracks.

Although our recordings were carried out in CA1, we believe that what we observed could be a reflection of the output of the recurrent cellular assemblies from upstream regions (CA3 or entorhinal cortex). During running on a familiar track, some of the cells in the postulated upstream cellular assemblies fire sequentially at spatial locations while others, although connected anatomically to these cells, remain silent. The lack of expression of preplay sequences during Fam-Run may reflect their state-dependent suppression or subthreshold activation during these exploratory behaviours. Owing to increased net excitation during rest periods predominantly during ripples21, some of these silent cells together with some of the familiar track cells are activated above threshold and fire in a certain sequence. Their sequence of activation may be determined in part by their functional connectivity within the hippocampal formation network. Some of these sequences may in turn be activated on a novel track as place cell sequences (Supplementary Fig. 8). The activation of the novel place cell sequences during running may strengthen their pre-existing assembly organization manifested during preplay.

It could be argued that during Contig-Run the animals simply considered the novel arm to be an extension of the familiar arm and, thus, what we considered to be preplay events were replays of the previous runs on the familiar track. If this was the case, preplay events would not be expected to be found when the experience of the familiar track run is eliminated. This idea was refuted by the demonstration of frequent preplay events in the sleep box before the mice were transferred onto a novel linear track (de novo condition). Under this condition, the place cell sequences were more dynamic and a higher proportion of all spiking events correlated with the place cell sequences in these runs than in the later runs on novel linear tracks. These results suggest a shift in the relative contribution of internal22,23 and external drives in the formation of place cell sequences on encounter with a novel track. In the early phase, internal drives originating in the dynamic cellular assembly activities, which probably reflect numerous past experiences distinct from the current one and expressed as preplay, may have a greater role, whereas in the late phase, external drives that come from the specific set of stimuli of the current experience may dominate. Thus, place cell sequences on novel tracks seem to be products of a dynamic interplay between the internal and external drives.

Several previous studies did not reveal preplay7,8,10,20. Although it is difficult to pinpoint the apparent discrepancies between these studies and the present one, we suggest that the use of insufficiently sensitive methods (pairwise correlations) by some studies7,8,20 and small sample sizes by others10 might have precluded detection of preplay in previous work (see Supplementary Information for details). Data from the de novo condition (Fig. 4), in which we observed an even higher proportion of preplay events, have not been reported previously.

Our data showed that novel preplay events coexist in disjunction with familiar replay events during the rest periods on the familiar track. This and the finding that these preplay and replay events together make up fewer than one-quarter of all detected spiking events suggest that they are part of a dynamic repertoire of temporal sequences in the hippocampus that are past-experience dependent (replay) or future-experience expectant24 (preplay). Post-experience replay of place cell sequences during resting3–6 or slow-wave sleep8–10 has been proposed to have an important role in memory consolidation11,12. The temporal preplay of new place cell sequences during resting or sleep is consistent with a predictive function for the hippocampal formation25 and may contribute to accelerating learning26 when a new experience is introduced in multiple steps of increasing novelty.

METHODS SUMMARY

We recorded place cells from the CA1 area of the hippocampus with six independently movable tetrodes in four mice during sleep/rest sessions in the sleep box before any experience on linear tracks and during the first run session on a novel track. Following familiarization with the linear track, animals were subsequently allowed to explore a continuous (L-shaped) track in which the now familiar track and a new novel arm were made contiguous. To quantify the significance of the preplay and replay processes, spiking events in which at least four cells were active were detected during sleep/rest (speed, <1 cm s−1) periods in the sleep box or awake rest (speed, <2 cm s−1) periods at the ends of the familiar track and novel arm, predominantly during ripple epochs.

We calculated statistical significance at the P < 0.025 level for each event by comparing the rank-order correlation between the event sequence and the place cell sequence (template) with the distribution of correlation values from 200 templates obtained by shuffling the original order of the place cells. Proportions of significant events were calculated as the ratio between the number of significant events and the total number of spiking events. We calculated the overall significance of preplay or replay processes by comparing the distribution of correlation values of all events with the distribution of correlation values of shuffled templates (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).The significance of the proportion of significant events out of the total number of spiking events was determined as the binomial probability of observing the number of significant events (as successes) from the total number of spiking events (as independent trials), with a probability of success of 0.025 in any given trial. We reconstructed the position of the animal from the spiking activity emitted during resting periods using Bayesian decoding procedures6.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. A. Wilson for assistance with data acquisition, discussions and comments on an earlier version of the manuscript; J. O’Keefe, A. Siapas, F. Kloosterman, D. L. Buhl for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript; and F. Kloosterman for providing assistance with the line detection for the Bayesian decoding. This work was supported by NIH grants R01-MH078821 and P50-MH58880 to S.T., who was an HHMI Investigator in an earlier part of this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions S.T. and G.D. conceived the project jointly. G.D. designed and performed the experiments and the analyses. G.D. and S.T. wrote the paper.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.O’Keefe J, Nadel L. The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford Univ. Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science. 1993;261:1055–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.8351520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster DJ, Wilson MA. Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature. 2006;440:680–683. doi: 10.1038/nature04587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diba K, Buzsaki G. Forward and reverse hippocampal place-cell sequences during ripples. Nature Neurosci. 2007;10:1241–1242. doi: 10.1038/nn1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlsson MP, Frank LM. Awake replay of remote experiences in the hippocampus. Nature Neurosci. 2009;12:913–918. doi: 10.1038/nn.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson TJ, Kloosterman F, Wilson MA. Hippocampal replay of extended experience. Neuron. 2009;63:497–507. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson MA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal ensemble memories during sleep. Science. 1994;265:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.8036517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skaggs WE, McNaughton BL. Replay of neuronal firing sequences in rat hippocampus during sleep following spatial experience. Science. 1996;271:1870–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nádasdy Z, Hirase H, Czurko A, Csicsvari J, Buzsaki G. Replay and time compression of recurring spike sequences in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:9497–9507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09497.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee AK, Wilson MA. Memory of sequential experience in the hippocampus during slow wave sleep. Neuron. 2002;36:1183–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzsáki G. Two-stage model of memory trace formation: a role for “noisy” brain states. Neuroscience. 1989;31:551–570. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakashiba T, Buhl DL, McHugh TJ, Tonegawa S. Hippocampal CA3 output is crucial for ripple-associated reactivation and consolidation of memory. Neuron. 2009;62:781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebb DO. The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris KD, Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Dragoi G, Buzsaki G. Organization of cell assemblies in the hippocampus. Nature. 2003;424:552–556. doi: 10.1038/nature01834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragoi G, Buzsaki G. Temporal encoding of place sequences by hippocampal cell assemblies. Neuron. 2006;50:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson LT, Best PJ. Place cells and silent cells in the hippocampus of freely-behaving rats. J. Neurosci. 1989;9:2382–2390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-07-02382.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Neill J, Senior T, Csicsvari J. Place-selective firing of CA1 pyramidal cells during sharp wave/ripple network patterns in exploratory behavior. Neuron. 2006;49:143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang K, Ginzburg I, McNaughton BL, Sejnowski TJ. Interpreting neuronal population activity by reconstruction: unified framework with application to hippocampal place cells. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1017–1044. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson A, Redish AD. Neural ensembles in CA3 transiently encode paths forward of the animal at a decision point. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12176–12189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3761-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kudrimoti HS, Barnes CA, McNaughton BL. Reactivation of hippocampal cell assemblies: effects of behavioral state, experience, and EEG dynamics. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:4090–4101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-04090.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Czurko A, Mamiya A, Buzsaki G. Oscillatory coupling of hippocampal pyramidal cells and interneurons in the behaving rat. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:274–287. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00274.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dragoi G, Harris KD, Buzsaki G. Place representation within hippocampal networks is modified by long-term potentiation. Neuron. 2003;39:843–853. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pastalkova E, Itskov V, Amarasingham A, Buzsaki G. Internally generated cell assembly sequences in the rat hippocampus. Science. 2008;321:1322–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.1159775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black JE, Greenough WT. Advances in Developmental Psychology. Lawrence Erlbaum; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassabis D, Kumaran D, Vann SD, Maguire EA. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1726–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610561104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tse D, et al. Schemas and memory consolidation. Science. 2007;316:76–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1135935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.