Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to compare the incidence and clinical significance of transient versus persistent acute kidney injury (AKI) on acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Materials and Methods

The study was a retrospective cohort of 855 patients with STEMI. AKI was defined as an increase of ≥0.3 mg/dL in creatinine level at any point during hospital stay. The study population was classified into 5 groups: 1) patients without AKI; 2) patients with mild AKI that was resolved by discharge (creatinine change less than 0.5mg/dL compared with admission creatinine during hospital stay, transient mild AKI); 3) patients with mild AKI that did not resolve by discharge (persistent mild AKI); 4) patients with moderate/severe AKI that was resolved by discharge (creatinine change more than 0.5 mg/dL compared with admission creatinine, transient moderate/severe AKI); 5) patients with moderate/severe AKI that did not resolve by discharge (persistent moderate/severe AKI). We investigated 1-year all-cause mortality after hospital discharge for the primary outcome of the study. The relation between AKI and 1-year mortality after STEMI was analyzed.

Results

AKI occurred in 74 (8.7%) patients during hospital stay. Adjusted hazard ratio for mortality was 3.139 (95% CI 0.764 to 12.897, p=0.113) in patients with transient, mild AKI, and 8.885 (95% CI 2.710 to 29.128, p<0.001) in patients with transient, moderate/severe AKI compared to patients without AKI. Persistent moderate/severe AKI was also independent predictor of 1 year mortality (hazard ratio, 5.885; 95% CI 1.079 to 32.101, p=0.041).

Conclusion

Transient and persistent moderate/severe AKI during acute myocardial infarction is strongly related to 1-year all cause mortality after STEMI.

Keywords: Acute kidney injury, myocardial infarction, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common complication in hospitalized patients, especially in high risk patients such as those hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), congestive heart failure, sepsis, and those undergoing cardiac surgery.1-6 Recent studies suggest that in patients with AMI, AKI is associated with poor outcomes and independently predicts increasing in-hospital and long-term mortality.7-9

Previous investigations principally emphasized the relationship between baseline indicators of renal function and outcome.7,9-13 However, renal function during the acute phase of AMI may change rapidly and AKI can be resolved by discharge. In such patients, it is thought that AKI is not associated with high risk long-term follow up. By contrast, AKI after AMI can be partly or completely irreversible in some patients, resulting in profound impact on cardiovascular outcomes. Few studies have examined the association between exacerbation of renal function and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Furthermore, the prognostic value of transient versus persistent AKI for acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is unknown in Korea. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare the incidence and clinical significance of transient versus persistent AKI on acute STEMI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This study was a retrospective cohort of consecutive 855 patients (62±13 years, men 75.2%) who were admitted to Chonnam National University Hospital and whose discharge diagnosis was acute STEMI by ACC criteria.14 Between October 2005 and June 2008, a total of 921 patients presenting with acute STEMI were enrolled. To investigate the effects of AKI on the long term mortality, we excluded 66 patients who died during the hospital stay, and enrolled remaining 855 patients who were discharged from hospital in stable condition. On the other hand, to investigate the effects of AKI on the acute events, we analyzed in-hospital deaths separately to compare acute mortality according to AKI categories.

Definition of AKI

The cutoffs for AKI were based on absolute creatinine changes during hospitalization. AKI was defined as an increase of ≥0.3 mg/dL in creatinine level at any point during hospital stay.15-16 The severity of AKI was subdivided on evidence from previous studies which showed that changes in creatinine level of at least 0.5 mg/dL are associated with increased mortality in patients with AMI.7,9,11 Mild AKI was defined as peak creatinine ≥0.3-0.49 mg/dL higher than baseline creatinine level, and moderate/severe AKI as an increase in serum creatinine ≥0.5 mg/dL compared with admission creatinine at any point during the hospitalization. Patients were classified into 5 groups based on creatinine level changes during hospitalization.; Group 1) Patients without AKI; Group 2) Patients with mild AKI that was resolved by discharge (creatinine change less than 0.5 mg/dL compared with admission creatinine during hospital stay, transient mild AKI); Group 3) Patients with mild AKI that did not resolve by discharge (persistent mild AKI); Group 4) Patients with moderate/severe AKI that was resolved by discharge (creatinine change more than 0.5 mg/dL compared with admission creatinine, transient moderate/severe AKI); Group 5) Patients with moderate/severe AKI that did not resolve by discharge (persistent moderate/severe AKI).

Assessment of renal function

Laboratory data, including serum creatinine, was collected before coronary angiography on admission. Venous blood samples were obtained at 24, 48 and 72 hr thereafter. Pre-discharge creatinine was measured on the day of discharge or the day before discharge. The abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula was used to estimate glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2 from creatinine level.17

Study endpoint

The primary endpoint was 1 year all cause mortality. After hospital discharge, clinical endpoint information was acquired by contacting each patient individually and reviewing hospital course if the patient had been re-hospitalized.

Statistical assesment

Continuous variables are demonstrated as either means (±SD) or medians, and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. We compared baseline characteristics of the groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and by the χ2 statistic for categorical variables. Using Kaplan Meier method, event-free survival was estimated and curves were compared with log-rank test. To determine the relation between AKI categories and inhospital mortality, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were examined. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to assess the relationship between AKI categories and 1-year mortality after adjustments to the variables. Analyses were adjusted for age, gender, heart rate on admission, Killip class II-IV, estimated glomerular filtration rate, left ventricular ejection fraction, and medication (aspirin, beta blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme ACE inhibitors, and statin). A p value less than 0.05 was deemed as significant. Statistical analysis was done with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS 17.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

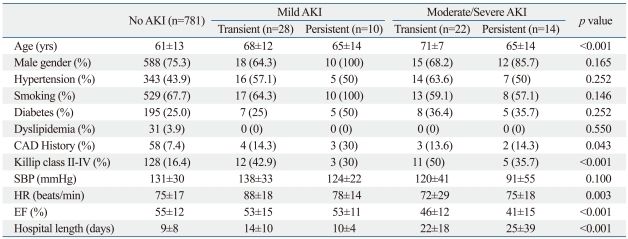

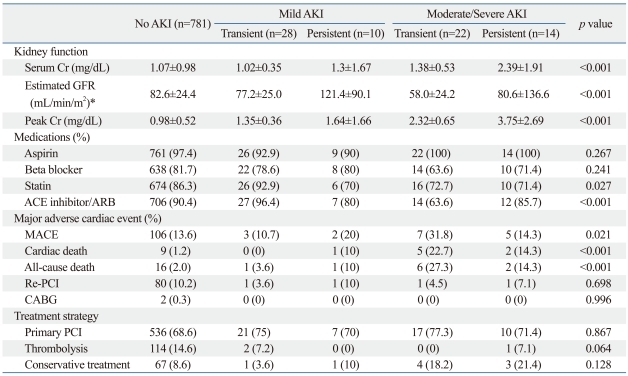

Eight hundreds fifty five patients were included in the present study (patients without AKI: n=781, 91.3%, patients with AKI; n=74, 8.7%). During the hospital course, mild AKI occurred in 38 (4.4%) patients and moderate/severe AKI in 36 (4.2%). Mild AKI was transient in 28 (73.7%) patients, and moderate/severe AKI was transient in 22 (61.1%) patients. Table 1 and 2 list baseline clinical characteristics of patients based on AKI categories. More severe AKI during the hospital course was associated with older age, higher Killip class and heart failure (ejection fraction <45%). Patients with AKI had higher creatinine level at baseline, higher peak creatinine during the hospital course, present with lower ejection fraction compared with the patients without AKI. Use of statin, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers was less frequent in more severe AKI. However, estimated GFR was the lowest in the group with transient moderate/severe AKI.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

AKI, acute kidney injury; SBP, systolic blood pressure; CAD, coronary arterial disease; EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate.

Table 2.

Baseline Kidney Function, Medical History and Major Adverse Cardiac Event

AKI, acute kidney injury; GFR, Glomerular filtration rate; Cr, creatinine; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft.

*On the basis of abbreviated MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) study equation.

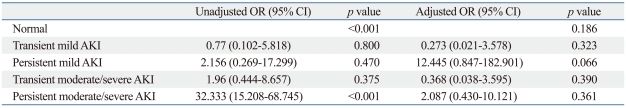

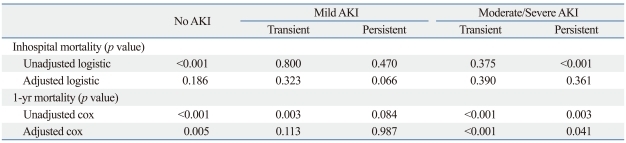

Relation of AKI and inhospital mortality

A total of 66 (7.2%) deaths occurred in hospital, with 25 (37.9%) deaths occurring in patients with acute kidney injury. Univariate logistic regression showed that persistent moderate/severe AKI was associated with a statistically significant increase of inhospital mortality. However, after adjustment for other risk variables, there was no association with AKI categories and in hospital mortality.

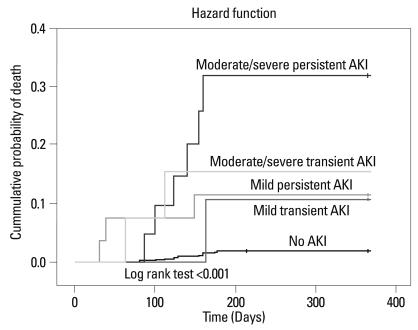

Relation of AKI and 1 year mortality

The median duration of follow-up after hospital discharge was 358 days. Of the 855 patients who survived their index hospitalization, a total of 25 (2.9%) deaths occurred during the follow-up period. Fig. 1 illustrates Kaplan-Meier survival in patients with AKI groups during follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the AKI groups showed significant differences of 1-year mortality after hospital discharge statistically. In each of the AKI groups, persistent moderate/severe AKI group showed lower probability of event-free survival compared with the other groups. Also, during the follow-up period, probability of death increased with increasing degrees of AKI.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to acute kidney injury categories. AKI, acute kidney injury.

The results of a multivariable cox proportional hazards model adjusting for other clinical variables of mortality are shown in Table 3 and 4. After adjustments for other risk variables including baseline estimated GFR and other clinical variables, there was no differences in 1-year mortality risk between transient mild AKI group and group without AKI. On the other hand, transient moderate/severe AKI was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio of 8.885 compared with group without AKI. Patients with persistent moderate/severe AKI had the highest all-cause of mortality compared with other groups (hazard ratio, 5.885; 95% CI 1.079 to 32.101, p=0.046).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic Regression Model for Inhospital Mortality According to Acute Kidney Injury Categories

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval.

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Logistic Regression and Cox Proportional Hazards Model for Mortality According to Acute Kidney Injury Categories*

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval.

*The final model adjusted for age, gender, estimated glomerular filtration rate, history of hypertension, diabetes, smoking, previous myocardial infarction, Killip class, heart rate and blood pressure on admission, medical therapy (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers) and left ventricular ejection fraction.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, AKI occurred in 74 (8.7%) patients during hospital course with STEMI who survived their index hospitalization. After acute stage of myocardial infarction, improvement of renal function within the index hospitalization revealed 73.7% of patients in mild AKI and 61.1% of patients in moderate/severe AKI. Patients developing AKI have worse baseline renal function and are more likely to present higher peak serum creatinine level. Baseline estimated GFR was the lowest in transient moderate/severe AKI group and peak serum creatinine was the highest in persistent moderate/severe AKI group. More severe AKI group showed longer hospital lengths. It is thought that there were more combined complications in severe AKI. Furthermore, in patients with transient mild AKI and transient moderate/severe AKI, there was no association with prognostic significance of 1-year all cause mortality after STEMI. Especially in mild transient AKI group, outcome of the group was similar to that of patients without AKI. Although it did not completely exclude absolute impacts and many questions about the relationship between renal dysfunction and mortality after AMI, several studies suggested that increment of serum creatinine level during admission is a significant independent predictor of mortality, especially in the setting of decompensated heart failure2,18 and AMI.19 However, our result showed that transient mild AKI did not affect long-term mortality in STEMI. In patients with mild transient AKI and moderate/severe transient AKI, there was no association with prognostic significance of 1-year all cause mortality, suggesting that transient mild or moderate/severe AKI represent a reversible renal impairment and do not affect long term mortality if corrected.

To investigate the effects of AKI on the acute events, we analyzed inhospital deaths separately according to acute kidney injury categories, and found that AKI has no association with inhospital mortality after adjustment for clinical predictors of mortality among patients with STEMI. These findings suggest that impaired renal function after STEMI is an independent predictor of 1-year mortality, but not of inhospital mortality. These observations are different from other study.7 Differences may be attributed to different races, measurement methods of serum creatinine and enrolled size.

Previous investigators have demonstrated that baseline renal dysfunction or CKD is associated with poor outcomes during short and intermediate-term follow up after AMI20-24 or acute coronary syndromes.25-27 The present study showed transient and persistent moderate/severe AKI as a risk factor for all cause mortality after STEMI. This means that worsening renal dysfunction and baseline renal dysfunction specifically define a group at a very high risk for mortality and may reflect underlying mechanisms that adversely affect both cardiac and renal function.7

AKI is a complex multifactorial phenomenon, preconditioned by underlying renal dysfunction and modulated by multiple contributing factors.28 For example, neurohormonal factors,29 such as norepinephrine, rennin-angiotensin, vasopressin, and endothelin, may affect renal function and play a role in renal dysfunction, modulating post infarct left ventricular remodeling.30-32 Also, volume depletion, the use of contrast media,33 and medical treatment such as diuretics or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blocker may affect renal dysfunction in reversible manner. Even though these factors may affect renal function and the outcomes of AMI, there are few studies regarding the incidence and clinical impact of transient versus persistent AKI in patients with AMI. Therefore, understanding the impact of transient versus persistent AKI on acute mortality and long-term outcomes is expected to assist with guiding follow up care for patients with acute myocardial infarction after discharge.

There are several points to be considered. Other predictors of AKI, such as current pharmacologic and procedural interventions for therapy of AMI that may be helpful to the heart but affect renal dysfunction, need to be considered.9 Furthermore, it has to be considered other types of therapeutic managements that can be applied to these patients to decrease the risk of mortality after AKI. AKI occurrences in MI patients should be monitored for given the increased risk of long-term death. Patients with AKI should be carefully monitored after discharge for potential development of related complications. Our study has several limitations. Because of methodological limitations inherent in retrospective analyses, our data cannot include the volume of contrast. Therefore, we did not address the influence of contrast volume that was administered during percutaneous coronary intervention. In addition, patients with poorer general condition are more likely to have longer hospitalizations and, hence, performed more frequent renal function studies including blood sampling, thus there has been the increasing probability of serum creatinine level change detection.

In conclusion, the present study shows that hemodynamic changes in renal function are common in AMI that is associated with long term mortality, especially in transient and persistent moderate/severe AKI.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A084869).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.de Mendonça A, Vincent JL, Suter PM, Moreno R, Dearden NM, Antonelli M, et al. Acute renal failure in the ICU: risk factors and outcome evaluated by the SOFA score. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:915–921. doi: 10.1007/s001340051281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman DE, Butler J, Wang Y, Abraham WT, O'Connor CM, Gottlieb SS, et al. Incidence, predictors at admission, and impact of worsening renal function among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoste EA, Lameire NH, Vanholder RC, Benoit DD, Decruyenaere JM, Colardyn FA. Acute renal failure in patients with sepsis in a surgical ICU: predictive factors, incidence, comorbidity, and outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1022–1030. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000059863.48590.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lassnigg A, Schmidlin D, Mouhieddine M, Bachmann LM, Druml W, Bauer P, et al. Minimal changes of serum creatinine predict prognosis in patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1597–1605. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130340.93930.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaño F, Junco E, Pascual J, Madero R, Verde E The Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. The spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit compared with that seen in other settings. Kidney Int Suppl. 1998;66:S16–S24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakar CV, Worley S, Arrigain S, Yared JP, Paganini EP. Influence of renal dysfunction on mortality after cardiac surgery: modifying effect of preoperative renal function. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1112–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldberg A, Hammerman H, Petcherski S, Zdorovyak A, Yalonetsky S, Kapeliovich M, et al. Inhospital and 1-year mortality of patients who develop worsening renal function following acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005;150:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jose P, Skali H, Anavekar N, Tomson C, Krumholz HM, Rouleau JL, et al. Increase in creatinine and cardiovascular risk in patients with systolic dysfunction after myocardial infarction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2886–2891. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassnigg A, Schmidlin D, Mouhieddine M, Bachmann LM, Druml W, Bauer P, et al. Minimal changes of serum creatinine predict prognosis in patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1597–1605. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130340.93930.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chertow GM, Normand SL, Silva LR, McNeil BJ. Survival after acute myocardial infarction in patients with end-stage renal disease: results from the cooperative cardiovascular project. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:1044–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown JR, Cochran RP, Dacey LJ, Ross CS, Kunzelman KS, Dunton RF, et al. Perioperative increases in serum creatinine are predictive of increased 90-day mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2006;114:I409–I413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loef BG, Epema AH, Smilde TD, Henning RH, Ebels T, Navis G, et al. Immediate postoperative renal function deterioration in cardiac surgical patients predicts in-hospital mortality and long-term survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:195–200. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2003100875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined--a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:959–969. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative workgroup. Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204–R212. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith GL, Vaccarino V, Kosiborod M, Lichtman JH, Cheng S, Watnick SG, et al. Worsening renal function: what is a clinically meaningful change in creatinine during hospitalization with heart failure? J Card Fail. 2003;9:13–25. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2003.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouzas-Mosquera A, Vázquez-Rodríguez JM, Peteiro J, Alvarez-García N. Acute kidney injury and long-term prognosis after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:87. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright RS, Reeder GS, Herzog CA, Albright RC, Williams BA, Dvorak DL, et al. Acute myocardial infarction and renal dysfunction: a high-risk combination. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:563–570. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson CM, Pinto DS, Murphy SA, Morrow DA, Hobbach HP, Wiviott SD, et al. Association of creatinine and creatinine clearance on presentation in acute myocardial infarction with subsequent mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1535–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadeghi HM, Stone GW, Grines CL, Mehran R, Dixon SR, Lansky AJ, et al. Impact of renal insufficiency in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:2769–2775. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103623.63687.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shlipak MG, Heidenreich PA, Noguchi H, Chertow GM, Browner WS, McClellan MB. Association of renal insufficiency with treatment and outcomes after myocardial infarction in elderly patients. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:555–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh CR, O'Donnell CJ, Camargo CA, Jr, Giugliano RP, Lloyd-Jones DM. Elevated serum creatinine is associated with 1-year mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2002;144:1003–1011. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.125504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Suwaidi J, Reddan DN, Williams K, Pieper KS, Harrington RA, Califf RM, et al. Prognostic implications of abnormalities in renal function in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2002;106:974–980. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027560.41358.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dumaine R, Collet JP, Tanguy ML, Mansencal N, Dubois-Randé JL, Henry P, et al. Prognostic significance of renal insufficiency in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (the Prospective Multicenter SYCOMORE study) Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1543–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman RV, Mehta RH, Al Badr W, Cooper JV, Kline-Rogers E, Eagle KA. Influence of concurrent renal dysfunction on outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and implications of the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:718–724. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02956-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann JF, Gerstein HC, Pogue J, Bosch J, Yusuf S. Renal insufficiency as a predictor of cardiovascular outcomes and the impact of ramipril: the HOPE randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:629–636. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petersen CL, Nielsen JR, Petersen BL, Kjaer A. Catecholaminergic activation in acute myocardial infarction: time course and relation to left ventricular performance. Cardiology. 2003;100:23–28. doi: 10.1159/000072388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–582. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fraccarollo D, Hu K, Galuppo P, Gaudron P, Ertl G. Chronic endothelin receptor blockade attenuates progressive ventricular dilation and improves cardiac function in rats with myocardial infarction: possible involvement of myocardial endothelin system in ventricular remodeling. Circulation. 1997;96:3963–3973. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsutamoto T, Wada A, Hayashi M, Tsutsui T, Maeda K, Ohnishi M, et al. Relationship between transcardiac gradient of endothelin-1 and left ventricular remodelling in patients with first anterior myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:346–355. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Marana I, Lauri G, Campodonico J, Grazi M, et al. N-acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropathy in primary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2773–2782. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]