Abstract

Indoor solid fuel combustion is a dominant source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and oxygenated PAHs (OPAHs) and the latter are believed to be more toxic than the former. However, there is limited quantitative information on the emissions of OPAHs from solid fuel combustion. In this study, emission factors of OPAHs (EFOPAH) for nine commonly used crop residues and five coals burnt in typical residential stoves widely used in rural China were measured under simulated kitchen conditions. The total EFOPAH ranged from 2.8±0.2 to 8.1±2.2 mg/kg for tested crop residues and from 0.043 to 71 mg/kg for various coals and 9-fluorenone was the most abundant specie. The EFOPAH for indoor crop residue burning were 1~2 orders of magnitude higher than those from open burning, and they were affected by fuel properties and combustion conditions, like moisture and combustion efficiency. For both crop residues and coals, significantly positive correlations were found between EFs for the individual OPAHs and the parent PAHs. An oxygenation rate, Ro, was defined as the ratio of the EFs between the oxygenated and parent PAH species to describe the formation potential of OPAHs. For the studied OPAH/PAH pairs, mean Ro values were 0.16 ~ 0.89 for crop residues and 0.03 ~ 0.25 for coals. Ro for crop residues burned in the cooking stove were much higher than those for open burning and much lower than those in ambient air, indicating the influence of secondary formation of OPAH and loss of PAHs. In comparison with parent PAHs, OPAHs showed a higher tendency to be associated with particulate matter (PM), especially fine PM, and the dominate size ranges were 0.7 ~ 2.1 µm for crop residues and high caking coals and < 0.7 µm for the tested low caking briquettes.

Introduction

As a group of derivatives of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), oxygenated PAHs (OPAHs) containing one or more oxygen(s) attached to the aromatic structure are persistent and mobile in environment and tend to be more toxic than the parent PAHs1, 2. Mutagenicity of OPAHs, especially several ketones and quinones like benzanthrone (BZO) and anthraquinone (ATQ), was demonstrated in a human cell based mutation assay3. And, it was thought that OPAHs may affect human health via the formation of proteins and DNA adducts, the depletion of glutathione, and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can enhance the oxidative stress4, 5. Strong positive correlations between ROS generation ability of ambient particulate matter (PM) and measured quinones were found in ambient samples from Fresno, CA6. In addition, OPAHs were also suggested as endocrine disruptors with estrogenic activity and high cytotoxicity1, 7.

OPAHs can be generated directly from primary fuel combustion or from secondary formation through radical reactions with PAHs or other precursors1, 8, and they have been widely detected in ambient air and other media1, 2, 8–11. Of the OPAHs found in combustion emissions, polycyclic aromatic ketones, like 9-fluorenone (9FO) and BZO are often the most abundant, and polycyclic aromatic quinones, including ATQ and benz[a]anthracene-7, 12-dione (BaAQ), are the second largest group8–11.

In ambient air, 9FO, ATQ, BZO, and BaAQ are also among the most abundant OPAH species9–13. OPAH concentrations in air (several pg/m3 to lower ng/m3) were often reported at the same order of magnitude as those of PAHs1. It was reported that and mean concentrations of 9FO were 3577, 2157, 888 pg/m3 in urban, sub-urban, and rural areas, accounting for 60% of total nine OPAHs ranged up to 6908 pg/m3 in France10. In the Beijing-Tianjin area, average concentrations of PM bound ATQ and BaAQ were 304±103 and 229±129 pg/m3 in summer of 200913. Though it is believed that OPAHs can be from either primary combustion or secondary formation, current data are too scarce to distinguish the predominance of primary and secondary sources, which vary between compound site and sampling period1, 6.

Solid fuels, like crop residues and coals, are widely used for cooking and heating in developing countries, especially in rural areas. Solid fuel combustion is one of the most important sources of indoor pollutants including PAHs, and estimated to be one of the largest causes of premature mortality14. In China, it was estimated that indoor combustion of crop residues and coals contributed approximately 35% and 4% of total PAH emissions in 200315. It is reasonable to expect that solid fuel combustion is also an important emission source of OPAHs, although the emission inventory of primary OPAHs has not been reported. One difficulty in developing an emission inventory for OPAHs for solid fuel is lack of information on emission factors (EFs), while EFs for parent PAHs (EFPAH) are more widely reported. To the best of our knowledge, the only EFOPAH data available for biomass burning were those from crop residue burning in an open-field experiment and from wood burnt in a stove and a fireplace16, 17. It was reported that EFs were 0.022 ~ 0.31 mg/kg for 9FO (EF9FO), 0 ~ 0.042 mg/kg for ATQ (EFATQ), and 0.60 ~ 0.95 mg/kg for BZO (EFBZO) for open-field burning of wheat and rice16. EF9FO and EFATQ for oak burning were 2.6 and 0.32 mg/kg in the woodstove, and 0.59 and 4.2 mg/kg in the fireplace, respectively17.

The main objective of this study was to determine EFs for OPAHS (EFOPAH) from residential combustion of solid fuels, including crop residues and coals, which are often used in rural China. In addition, the influence of fuel properties and combustion conditions on the emissions, size distributions of PM associated OPAHs, and gas-particle partitioning of freshly emitted OPAHs were also addressed.

Method

Fuels and Combustion

Experimental facilities, including actual residential stoves, were the same as those presented in two previous papers18, 19 and summarized here in brief. The solid fuels studied included nine crop residues (rice, wheat, corn, cotton, soybean, horsebean, peanut, seasame, and rape), contributing more than 90 % of total crop residues produced in China, and five coals (two honeycomb briquettes made of either anthracite from Beijing or bituminous from Taiyuan, and three raw chunk coals from Yulin and Taiyuan). Fuel properties including C, H, N content, moisture, ash content, heating value and volatile matter content (VM) of coals were measured18.

The combustion experiments were conducted in the simulated kitchen following the practice of the local residents do in daily lives, and for the same fuel type, combustion experiments were done in duplicate. Crop residues were burned in a typical wok stove which was connected to a heating bed (known as “Kang”). For coal combustion, a cast-iron stove was used. Both stoves are widely used in rural China. The smoke from the cooking stove (through the “Kang”) and coal stove (through a stainless hood and pipe) entered a mixing chamber (4.5 m3) with a built-in fan, where all sampling and measurements were conducted. CO and CO2 were measured by an online nondispersive infrared sensor every 2 s. Combustion duration, temperatures, and relative humidity in the mixing chamber were also recorded18, 19.

Sample Collection and Extraction

Particulate and gaseous phase OPAHs were collected on quartz fiber filters (QFFs, 22 mm in diameter) and polyurethane foam plugs (PUF, Supelco, 22 mm diameter × 7.6 cm), respectively, using active samplers (Jiangsu, China) at a flow rate of 1.5 l/min. A nine stage cascade impactor (FA-3, China) with glass fiber filters was used to collect PM with different aerodynamic diameters (Da) (< 0.4, 0.4 ~ 0.7, 0.7 ~ 1.1, 1.1 ~ 2.1, 2.1 ~ 3.3, 3.3 ~ 4.7, 4.7 ~ 5.8, 5.8 ~ 9.0, and 9.0 ~ 10.0 µm) at a flow rate of 28.3 l/min.

PUF samples were Soxhlet extracted with 150 ml of dichloromethane for 8 h, and filters were extracted using 25 ml of a hexane/acetone mixture (1:1, v/v) and a microwave accelerated system (CEM Mars Xpress, USA)13. Microwave power was set at 1200 W and the temperature was increased to 110 °C in 10 min and held for another 10 min. The extracts were concentrated to about 1 ml and then transferred to a silica/alumina gel column for cleanup. The column was eluted with 25 ml of hexane (discarded) and 70 ml hexane/dichloromethane (1:1, v/v). The eluate was finally concentrated to 1 ml.

GC-NCI-MS Detection and Quality Control

OPAH analysis was performed using a gas chromatography (GC, Agilent 6890) connected to a mass spectrometer (MS, Agilent 5975) equipped with a HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) in negative chemical ionization mode (NCI). The oven temperature was programmed as: initial temperature at 60 °C, increased to 150 °C at a rate of 15 °C/min, and then to 300°C at 5° C/min held for 15 min. 1 µl sample was injected in splitless mode. High-purity helium with flow rate of 1.0 l/min and methane at 2.5 l/min were used as the carrier and reagent gas, respectively. Compounds were identified and quantified based on the retention time and selected ions (SIM) of the standards (J&W Chemical, USA). Since labeled OPAHs were not commercially available, two deuterated nitro-PAHs (1-nitroanthcene-d9 and 1-nitropyrene-d9, J&W Chemical Ltd., USA) were used as internal standards10, 11. Four target compounds quantified included two polycyclic aromatic ketones (9FO (m/z=180) and BZO (m/z=230)) and two quinones (ATQ (m/z=208) and BaAQ (m/z=258)). Preparation of PUFs, filters, silica/alumina, organic reagents and glassware are presented elsewhere in detail19.

Samples were collected before the combustion and measured as procedure blanks. Instrument detection limits were 0.06, 0.24, 0.13, and 0.12 ng for 9FO, ATQ, BZO, and BaAQ, respectively. Method detection limits of these four targets were 0.32, 0.60, 0.33, 0.25 ng/ml for gaseous samples, and 0.11, 0.30, 0.44, 0.24 ng/ml for particulate samples. Recoveries of the analysis procedure, determined by spiking the standards, were 49±13, 86±20, 104±10, and 78±8 % for gaseous 9FO, ATQ, BZO, and BaAQ, and 51±3, 81±10, 87±14, and 71±7 % for particulate bound 9FO, ATQ, BZO, and BaAQ, respectively.

Data Analysis

EFs were measured based on the carbon mass balance method assuming that the carbon burnt during fuel combustion was emitted in the forms of gaseous CO, CO2, total hydrocarbon, and total carbon in particulate matter20. EFs reported here were emissions from the whole burning cycle as sampling lasted over the whole burning process instead of a short time interval. Since it is believed that various factors, like moisture and MCE may influence the formation and emission of pollutants, future work on variations of EFs over the course of the burning process might be interesting. Modified combustion efficiency (MCE, defined as CO2/ (CO+CO2)), burning rate and carbon release rate were calculated to quantitatively describe the combustion status. Stastistica (v5.5, StatSoft) was applied for data analysis. It should be noted that the following discussion was based on the limited combustion experiments under given conditions. Taking the large variations of measured EFs into consideration, the results should not be simply generalized.

Results and Discussion

OPAH Emission Factors for Solid Fuel Combustion

Total EFs of the 4 OPAHs combined for the 9 crop residues studied ranged from 2.8±0.2 for soybean to 8.1±2.2 mg/kg for wheat with a mean and standard deviation of 4.5±2.0 mg/kg. Among the 4 compounds, 9FO was the most abundant (2.0±0.8 mg/kg), followed by BZO (1.4±0.7 mg/kg), ATQ (1.0±0.4 mg/kg), and BaAQ (0.11±0.04 mg/kg), as shown in Table 1. For the 5 coal tested, total EFs were 0.049±0.009 and 0.29±0.02 mg/kg for the 2 types of honeycomb briquettes and 8.8±4.3, 40±42, and 0.53±0.04 mg/kg for the 3 different raw chunk coals, respectively. 9FO (0.034±0.009 and 0.22±0.01 mg/kg for Beijing and Taiyuan briquettes, respectively) was the dominant specie from briquette combustion, while 9FO (3.3 ~ 12 mg/kg) and BZO (4.0 ~ 24 mg/kg) were the most abundant compounds for raw chunk coals.

Table 1.

Emission factors (mg/kg) of individual OPAHs for residential crop residue and coal combustions. Data shown are means and standard derivation from duplicated experiments.

| Fuel type | 9FO | ATQ | BZO | BaAQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop residue | Horsebean (Vicia faba) | 1.6±0.5×100 | 6.5±3.2×10−1 | 9.7±7.9×10−1 | 9.1±6.4×10−2 |

| Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) | 2.3×100 | 1.1×100 | 1.4×100 | 1.2×10−1 | |

| Soybean (Cassia agnes) | 1.4±0.3×100 | 5.7±0.5×100 | 7.7±0.1×10−1 | 6.2±0.5×10−2 | |

| Cotton (Anemone vitifolia) | 1.1±0.1×100 | 6.4±0.8×10−1 | 1.2±0.0×100 | 9.4±0.4×10−2 | |

| Rice (Oryza sativa) | 3.1±1.5×100 | 1.2±0.3×100 | 2.6±1.8×100 | 1.2±0.6×10−1 | |

| Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | 3.4±1.5×100 | 1.8±0.4×100 | 2.7±0.3×100 | 2.1±0.2×10−1 | |

| Rape (Brassica napus) | 2.2±0.4×100 | 1.2±0.4×100 | 1.6±0.3×100 | 1.4±0.4×10−1 | |

| Sesame (Sesamum indicum) | 1.5±0.5×100 | 1.1±0.4×100 | 4.9±0.4×10−1 | 7.8±2.8×10−2 | |

| Corn (Zea mays) | 1.3±0.1×100 | 6.7±1.6×10−1 | 9.2±5.2×10−1 | 8.2±3.1×10−2 | |

| Coal | Honeycomb briquette, Beijing | 3.4±0.9×10−2 | 6.6±0.6×10−3 | 7.0±0.1×10−3 | 5.2±3.6×10−4 |

| Honeycomb briquette, Taiyuan | 2.2±0.0×10−1 | 3.2±0.8×10−2 | 3.6±0.9×10−2 | 5.2±0.6×10−3 | |

| Raw Chunk, Taiyuan | 3.3±3.0×100 | 1.3±0.8×100 | 4.0±0.4×100 | 1.7±0.1×10−1 | |

| Raw Chunk-A, Yulin | 1.2±1.3×101 | 4.0±3.8×100 | 2.4±2.5×101 | 3.7±3.5×10−1 | |

| Raw Chunk-B, Yulin | 2.3±0.5×10−1 | 2.1±0.0×10−1 | 7.2±0.3×10−2 | 1.9±0.7×10−2 | |

Although EFOPAH for various crop residues were significant different (p < 0.05), they were within the same order of magnitude. On the other hand, EFOPAH of the tested coals varied 3 orders of magnitude with EFOPAH of chunk coals higher than those of honeycomb briquettes. Similar differences between honeycomb briquettes and chunk coals have been found for other pollutants. For example, EFs of PM, EC and parent PAHs from chunk coals were about 1 ~ 2 orders of magnitude higher than those from briquettes18, 21.

Hays et al. measured EFOPAH from open field burning of rice and wheat residues and reported EF9FO, EFATQ, and EFBZO of 0.022–0.31, 0–0.042, and 0.60–0.95 mg/kg, respectively16. As such, our results suggest that EFOPAH of crop residue from indoor stove burning are 1 ~ 2 orders of magnitude higher than those from open field burning. However, they are similar to those of wood burning in indoor stoves (2.6±0.6 and 0.32±0.28 mg/kg for EF9FO and EFATQ)17. The relatively high OPAH emissions from indoor burning can be explained by the different amount of oxygen supply resulting in lower combustion efficiencies and relatively high temperature in the enclosed residential stoves due to low heat loss15, 18. Similar differences were also found in parent PAH emissions. EFPAH were reported to be about one order of magnitude higher for indoor wheat burning (0.4–33 mg/kg) when compared to open burning (0.0–6.0 mg/kg)15. Considering that solid fuels are and will be the main fuels used by majority of rural residents in China, exposure risk to the relatively high toxic pollutants including PAHs and OPAHs emitted from indoor solid fuel combustions should be highlighted and arise more attention.

EFs of various combustion-generated pollutants are affected by a number of factors including fuel types, fuel properties and combustion conditions8, 16–22, and the main factors could be identified to develop a model for predicting EFS18, 19, 21. Here, a similar approach was undertaken to quantitatively address the influence of fuel properties and combustion conditions on EFOPAH in the current study. The detailed results are provided in the Supporting Information (S1, Table S1, S2 and Figure S1). In brief, both MCE and moisture negatively affected EFOPAH of crop residues (p < 0.05). A relatively low MCE was favorable for incomplete combustion, while relatively high moistures could reduce combustion temperatures resulting in lower OPAH formations8. Suppressed parent PAH formation resulted from relatively higher moistures may also be responsible for the subsequently lower OPAH emissions8, 22. Since these two factors explained 56 ~ 77 % of the total variation in the measured EFOPAH for crop residues, a set of regression models with moisture (M) and MCE as independent variables were developed for predicting EFOPAH. For example, EF of 9FO (EF9FO) can be estimated based on the following equation:

Similar regression models were also developed for EFOPAH of coal combustion in the residential stove, which were significantly affected by heating value and VM (p < 0.05), in addition to MCE and moisture. Relatively high heating values of the coal could result in relatively high temperatures in the stove, and were favorable for the OPAH formation8, while higher VM were associated with less complete combustion23. Together, 42 ~ 52% of the total variations in EFOPAH for coals were captured by the regression models.

Relationship between OPAHs and Parent PAHs

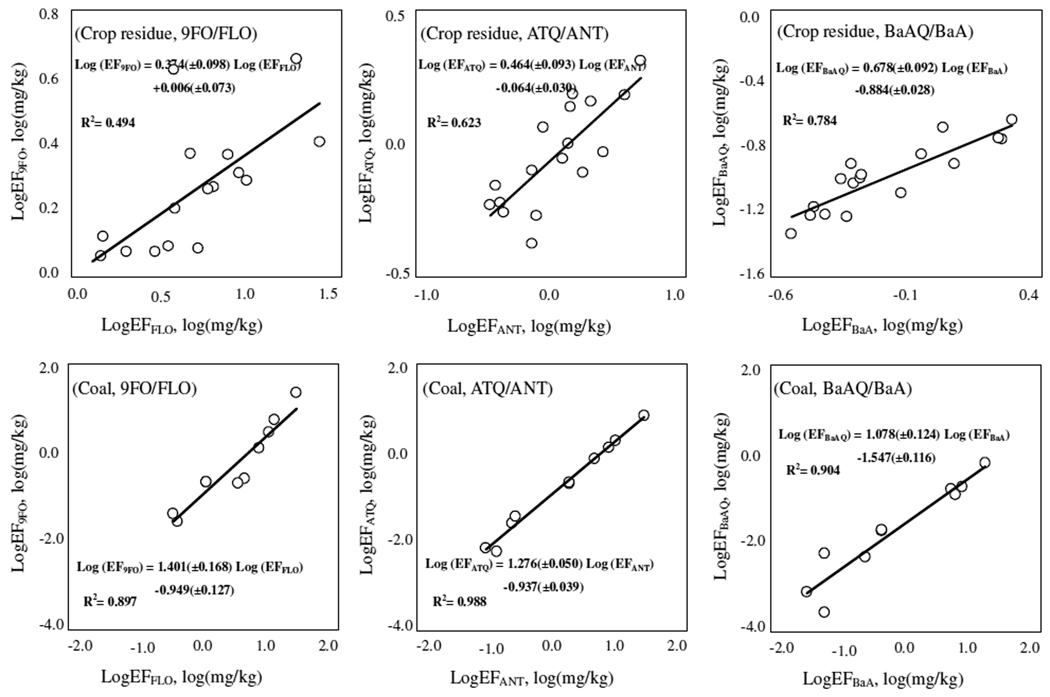

Parent PAHs generated from solid fuel combustion can be oxygenated to form OPAHs1, 8. In this study, emissions from crop residue and coal combustion were sampled and measured for OPAHs and parent PAHs simultaneously. EFPAH were presented previously19, 21 and are compared with EFOPAH here. Figure 1 presents correlations between the log-transformed EFOPAH and EFPAH for 3 pairs of OPAH/PAH compounds (9FO/FLO, ATQ/ANT, and BaAQ/BaA from left to right) for both crop residues (top row) and coals (bottom row). Significantly positive correlations (p < 0.05) are found and correlation coefficients were higher than 0.70 (n = 17) and 0.94 (n = 10) for crop residues and coals, respectively (S2, Table S3). Such positive correlations are expected because the regression analysis found that both EFPAH and EFOPAH depended on the same important factors including MCE, moisture, and VM content in similar ways19, 21.

Figure 1.

Relationship between the log-transformed EFOPAH and EFPAH from residential crop residue (top) and coal (bottom) combustions. The 3 pairs of OPAH/PAH from left to right are 9FO/FLO, ATQ/ANT, and BaAQ/BaA. There were 9 crop residues with 2 duplicates (one duplicate lost, n = 17) and 5 coals with 2 replicates (n = 10). Regression equations including coefficients and standard errors are also shown.

The linear relationship between log-transformed EFs of oxygenated and parent PAH species implies the quantitative dependence of the former on the latter. Such a relationship was characterized by defining an oxygenation rate (Ro) in this study as the quantity of a given OPAH emitted per unit quantity of its parent PAH emitted (EFOPAH/EFPAH). For the 3 pairs of OPAH/PAH studied, the calculated Ro were 0.40±0.18, 0.89±0.41, and 0.16±0.05 for 9FO/FLO, ATQ/ANT, and BaAQ/BaA from crop residue burning and 0.25±0.25, 0.14±0.08, and 0.03±0.02 for 9FO/FLO, ATQ/ANT, and BaAQ/BaA from coal combustion, respectively. It appeared that Ro values were significantly different among OPAH compounds and the measured Ro values of crop residue burning were significantly higher than those of coal burning (p < 0.05).

When the calculated Ro are plotted against EFPAH (S3, Figure S2), significant correlations are demonstrated, and it is interesting to see that the dependence of Ro on EFPAH was negative for crop residues but positive for coals. Since both EFPAH and EFOPAH are negatively correlated to fuel moisture and MCE of the crop residue combustion, the negative dependence of Ro on EFPAH suggests that the effects of MCE or moisture or both on the formation of parent PAHs were stronger than those on OPAH formation, leading to relatively smaller fractions of OPAHs formed when parent PAH emissions increased at relatively low MCE and moisture. On the other hand, high moisture is unfavorable for PAH generation due to the increased destruction rate by forming more radicals22, but might be favorable for oxygenation of PAHs. Different from those for crop residue burning, the Ro for 9FO/FLO and ATQ/ANT pairs from coal combustion were positively correlated to EFFLO and EFANT. Although many factors might influence the formation and emissions of OPAHs and parent PAHs, no significant correlation between Ro and any coal property or combustion condition was found (S3, Table S4 and S5). The interaction among these factors was likely the reason causing the insignificance. In future, more studies under controlled conditions are necessary to get insight to the phenomenon.

The reported data of EFOPAH and EFPAH for open-field burning of wheat and rice residues measured by Hays et al.,16 were used to calculate Ro of these pairs of OPAH/PAH for comparison with our results. It was found that Ro were 0.15 and 6.6 for 9FO/FLO and ATQ/ANT during open-field burning of wheat residue and 0.51 for 9FO/FLO for open-field burning of rice residue. These values were significantly different from what we derived for residential combustion of crop residues, and can be explained by very different combustion conditions between open-field combustion and enclosed burning in stoves where oxygen supply is limited, but temperatures are generally higher.

Reported ratios of OPAHs and parent PAHs measured in ambient air are usually higher than the Ro we directly measured for the freshly emitted compounds in the stack gases. In many cases, the measured OPAH concentrations in ambient air are the same order of magnitude of the parent PAH concentrations1. The concentrations of both parent PAHs and OPAHs in ambient air of Beijing-Tianjin area in summer, 2009 were reported, and the ratios of 9FO/FLO, ATQ/ANT, and BaAQ/BaA in ambient air were 2.9±1.1, 7.9±3.1, and 0.54±0.22, respectively13. These were 3 ~ 8 times of Ro for the crop residue burned in the residential stove, though indoor crop residue burning is expected to be the primary contributor to PAH emissions in the area15. Relatively high ratios in the filed are also reported for other areas. For example, the oxygenated ratios in the Marseilles ambient air in summer 2004 were at about 1.02, 1.82, and 1.55 for the three pairs, respectively10. The increase of the ratios in ambient air was likely due to the secondary formation of OPAHs, which could happen via the photochemical reactions of PAHs with ozone, hydroxyl, and nitrate radicals1, or due to faster loss of the parent PAHs. For example, it was suggested that in summer time, about 90% of phenanthraquinone in air of Los Angeles was from photochemical reaction during transport process24. It should be pointed out that until more data are collected, sound conclusions on relative importance of primary and secondary contributions to OPAHs in air could not be quantified.

Gas - Particle Partitioning of OPAHs

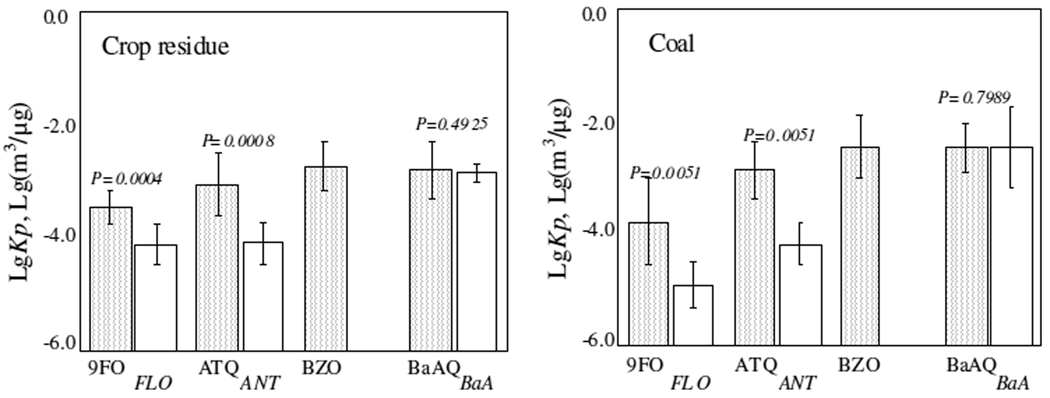

Similar to their parent PAHs, OPAHs are either in gaseous or condensed phases. Generally, those with relatively low molecular weight and high volatility occur dominantly in gaseous phase, while those with relatively high molecular weight and low volatility tend to associate with particles11. The partition of PAHs between gaseous and condensed phases can be described by gas-particle partition coefficients (KP), defined as: KP =F/(A×PM), where F and A are the particulate and gaseous phase concentrations (ng/m3), and PM was the concentration of co-emitted PM (µg/m3)25. The log-transformed KP for the freshly emitted OPAHs from crop residue and coal combustions are shown in Figure 2, and compared with those of co-emitted parent PAHs. Among the 4 OPAHs investigated in this study, parent PAH (benz[de]anthracene) of BZO is not included in the US EPA priority pollutant list and was not measured.

Figure 2.

The measured gas-particle partition coefficients (KP) of 4 OPAHs from crop residues (left panel) and coals (right panel). The results are compared with those of parent PAHs (except the parent PAHs for BZO which was not measured) emitted at the same time. The means and standard deviations are shown in log-scale.

Similar to those in ambient air11, KP of organic pollutants showed a general increasing trend as molecular weight increases. For both crop residue and coal combustion, KP values of 9FO and ATQ were significantly higher than their parent PAHs (p < 0.05) and the differences were as high as 0.6~1.3 orders of magnitude, primarily because the vapor pressures of 9FO (7.6×10−3 Pa) and ATQ (1.6×10−5 Pa) are significantly lower than those of FLO (1.7×10−1 Pa) and ANT (4.1×10−3 Pa)1. For high molecular weight compounds, their parent PAHs have quite low vapor pressures and are dominantly bound to particles, so differences in KP values between parent PAHs and OPAHs were not as large as those of low molecular weight ones. For example, calculated KP values of BaAQ (vapor pressure is 4.8×10−6 Pa) and those of BaA (vapor pressure is 1.5×10−5 Pa) was not significantly different (p > 0.05).

Partition of OPAHs between the gaseous and condensed phases is a temperature and moisture dependent process9–11. In this study, samples were collected from the mixture chamber where temperature and relative humidity ranged from 18~25°C and 44~60%, respectively. Coefficients of variation (standard variations divided by the means) of the log-transformed Kp of measured OPAHs from crop residue and coal combustions were 17~22% and 12~22 %. Since air temperature and relative humidity in outdoor environment could be very different from those in the mixing chamber, it is expected that the partitioning of OPAHs could change quickly after they released into ambient environment.

Gas-particle partitioning of organic chemicals is thought to be controlled by adsorption or absorption or both. The former is related to surface area and black carbon content of particles, while the absorption is associated with strong absorbents, such as organic matter (OC)26, 27. The mechanism(s) can be investigated by plotting Kp against subcooled liquid vapor pressure or octanol-air partition coefficient26, 27. Unfortunately, these physicochemical parameters are not available for the studied OPAHs. The only hint noted in this study was that the correlation between OPAHs and OC was more significant than that between OPAHs and BC (S2, Table S3). This result suggests that absorption might govern the partitioning of freshly emitted OPAHs, a similar mechanism for PAHs19, 21.

Size Distribution of Particulate Phase OPAHs

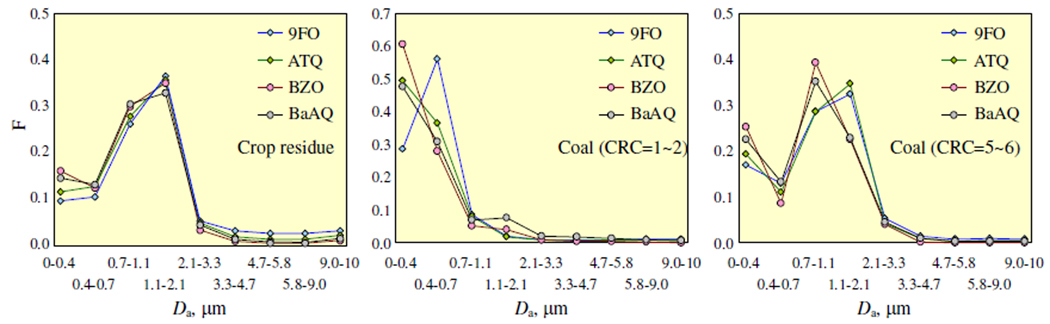

Size-fractionated samples collected found that the OPAHs from crop residue burning had a unimodal size distribution (Figure 3, left panel), dominantly found in the 1.1 ~ 2.1 µm size range (33 ~ 37 %), followed by those between 0.7 and 1.1 µm (26 ~ 31 %), similar to their parent PAHs19. About 83, 88, 94, and 91 % of particulate phase 9FO, ATQ, BZO, and BaAQ occurred in fine particles of PM2.1 (PM with Da ≤ 2.1 µm, which is the cut point most close to 2.5 µm). The simultaneously measured percentages of the co-emitted FLO, ANT, and BaA associated with PM2.1 were 51, 65, and 88 % respectively19. The somewhat higher fraction of OPAH in fine particles is consistent with the Kp values of OPAHs being higher than those of their parent PAHs (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Size distributions of particulate phase OPAHs from combustions of crop residues (left), low CRC coals (middle panel), and high CRC coals (right panel). The samples were fractionated into 9 fractions with different aerodynamic size using a nine-stage cascade impactor.

For coal combustion, similar to those of parent PAHs21, size distributions of PM-bound OPAHs can be classified into two categories based on the coal caking properties described by Char Residue Characteristics (CRC, ranged from 1 to 8, and the higher the CRC, the stronger the caking and swelling properties of the coal). Particulate phase OPAHs from the two briquettes and one raw chunk from Yulin (Chunk-2) with CRC of 1 or 2 were primarily found in fine particles with Da less than 0.7 µm (Figure 3, middle panel), while those from two other chunk coals with CRC of 5 and 6, were dominantly in particles with Da between 0.7 and 2.1 µm (Figure 3, right panel).

As expected, higher fraction of fine particle-bound OPAHs than parent PAHs was also revealed for residential coal combustion. For example, 17±6, 19±8, and 22±7 % of 9FO, ATQ, and BaAQ and 10±6, 13±9, and 17±9 % of FLO, ANT, and BaA occurred in PM0.4 (PM with Da ≤ 0.4 µm) from two higher caking raw coals21. High affinities of OPAHs to fine particles were also found in field9, 28. Such a tendency of accumulation in fine particles should be taken into consideration in risk assessment for human inhalation exposure to OPAHs since fine particles are readily penetrate into the deeper lung region after exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Funding for this study was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (40730737 and 41001343), the National Basic Research Program (2007CB407301), the Ministry of Environmental Protection (200809101), and NIEHS (P42 ES016465). We thank Dr. Mei Zheng (Georgia Institute of Technology) for proof reading and valuable comments.

Footnotes

Supporting Information available

Information concerning the influence of fuel properties and combustion conditions, relationship between EFOPAH and EFs of other co-emitted pollutants, and results of correlation analysis between Ro and fuel properties, combustion conditions and EFPAH, are provided and available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Literature Cited

- 1.Walgraeve C, Demesstere K, Dewulf J, Zimmermann R, van Langenhove H. Oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmospheric particulate matter: Molecular characterization and occurrence. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:1831–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundstedt S, White P, Lemieux C, Lynes K, Lambert I, Öberg L, Haglund P, Tysklind M. Sources, fate, and toxic hazards of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) at PAH-contaminated sites. Ambio. 2007;36:475–485. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[475:sfatho]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durant JL, Busby WF, Lafleur AL, Penman BW, Crespi CL. Human cell mutagenicity of oxygenated, nitrated and unsubstituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with urban aerosols. Mutat. Res. 1996;371:123–157. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1218(96)90103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li N, Hao MQ, Phalen RF, Hinds WC, Nel AE. Particulate air pollutants and asthma-a paradigm for the role of oxidative stress in PM-induced adverse health effects. Clin. Immunol. 2003;109:250–265. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton JL, Trush MA, Penning TM, Dryhurst G, Monks TJ. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung MY, Lazaro RA, Lim D, Jackson J, Lyon J, Rendulic D, Hasson AS. Aerosol-borne quinones and reactive oxygen species generation by particulate matter extracts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:4880–4886. doi: 10.1021/es0515957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidhu S, Gullett B, Striebich R, Klosterman J, Contreras J, DeVito M. Endocrine disrupting chemical emissions from combustion sources: diesel particulate emissions and domestic waste open burn emissions. Atmos. Environ. 2005;39:801–811. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzpatrick EM, Ross AB, Bates J, Andrews G, Jones JM, Phylaktou H, Pourkashanian M, Williams A. Emission of oxygenated species from the combustion of pine wood and its relation to soot formation. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2007;85:430–440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen JO, Dookeran NM, Taghizadeh K, Lafleur AL, Smith KA, Sarofim AF. Measurement of oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with a size-segregated urban aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997;31:2064–2070. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albinet A, Leoz-Garziandia E, Budzinski H, Villenave E. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrated PAHs and oxygenated PAHs in ambient air of the Marseilles area (South of France): concentrations and sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2007;384:280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albinet A, Leoz-Garziandia E, Budzinski H, Villenave E, Jaffrezo J. Nitrated and oxygenated derivatives of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air of two French alpine valleys Part 1: concentrations, sources and gas/particle partitioning. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreou G, Rapsomanikis S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their oxygenated derivatives in the urban atmosphere of Athens. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;172:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang WT. Ph.D. Dissertation. Beijing, China: Peking University; 2010. Regional Distribution and Air-Soil Exchange of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) and Their Derivatives in Beijing-Tianjin Area. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Smith KR. Household air pollution from coal and biomass fuels in China: Measurements, health impacts, and interventions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:848–855. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Dou H, Chang B, Wei Z, Qiu W, Liu S, Liu W, Tao S. Emission of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from indoor straw burning and emission inventory updating in China. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2008;1140:218–227. doi: 10.1196/annals.1454.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hays MD, Fine PM, Geron CD, Kleeman MJ, Gullett BK. Open burning of agricultural biomass: physical and chemical properties of particle-phase emissions. Atmos. Environ. 2005;39:6747–6764. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gullett BK, Touati A, Hays MD. PCDD/F, PCB, HxCBz, PAH, and PM emission factors for fireplace and woodstove combustion in the San Francisco Bay Region. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003;37:1758–1765. doi: 10.1021/es026373c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen G, Yang Y, Wang W, Tao S, Zhu C, Min Y, Xue M, Ding J, Wang B, Wang R, Shen H, Li W, Wang X, Russell AG. Emission factors of particulate matter and elemental carbon for crop residues and coals burned in typical household stoves in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:7157–7162. doi: 10.1021/es101313y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen G, Wang W, Yang Y, Ding J, Xue M, Min Y, Zhu C, Shen H, Li W, Wang B, Wang R, Wang X, Tao S, Russell AG. Emissions of PAHs from indoor crop residue burning in a typical rural stove: emission factors, size distributions and gas-particle partitioning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:1206–1212. doi: 10.1021/es102151w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Smith KR, Ma Y, Ye S, Jiang F, Qi W, Liu P, Khalil MAK, Rasmussen RA, Thorneloe SA. Greenhouse gases and other airborne pollutants from household stoves in China: a database for emission factors. Atmos. Environ. 2000;34:4537–4549. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen G, Wang W, Yang Y, Zhu C, Min Y, Xue M, Ding J, Li W, Wang B, Shen H, Wang R, Wang X, Tao S. Emission factors and particulate matter size distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from residential coal combustions in rural Northern China. Atmos. Environ. 2010;44:5237–5243. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu H, Zhu L, Zhu N. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions from straw burning and the influence of combustion parameters. Atmos. Environ. 2009;43:978–983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu WX, Dou H, Wei ZC, Chang B, Qiu WX, Liu Y, Tao S. Emission characteristics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from combustion of different residential coals in North China. Sci. Total Environ. 2009;407:1436–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eiguren-Fernandez A, Miguel AH, Lu R, Purvis K, Grant B, Mayo P, Di Stefano E, Cho AK, Froines J. Atmospheric formation of 9, 10-phenanthraquinone in the Los Angeles air basin. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:2312–2319. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pankow J. Review and comparative analysis of the theories on partitioning between the gas and aerosol particulate phases in the atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 1987;21:2275–2283. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lohmann R, Lammel G. Adsorptive and absorptive contributions to the gas-particle partitioning of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: state of knowledge and recommended parametrization for modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004;38:3793–3803. doi: 10.1021/es035337q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goss K, Schwarzenbach RP. Gas/solid and gas/liquid partitioning of organic compounds: critical evaluation of the interpretation of equilibrium constants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998;32:2025–2032. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albinet A, Leoz-Garziandia E, Budzinski H, Villenave E, Jaffrezo J. Nitrated and oxygenated derivatives of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the ambient air of two French alpine valleys Part 2: particle size distribution. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:55–64. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.