Although five-year survival rates for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are now over 80% in most industrialized countries1, not all children have benefited equally from this progress2. Ethnic differences in survival after childhood ALL have been reported in many clinical studies3-11, with poorer survival observed among African Americans or those with Hispanic ethnicity when compared with European American or Asian patients3-5. The causes of ethnic differences remain uncertain, although both genetic and non-genetic factors are likely important4,12. Interrogating genome-wide germline SNP genotypes in an unselected large cohort of children with ALL, we observed that the component of genomic variation that co-segregated with Native American ancestry was associated with the risk of relapse (P=0.0029), even after adjusting for known prognostic factors (P=0.017). Ancestry-related differences in relapse risk were abrogated by the addition of a single extra phase of chemotherapy, indicating that modifications to therapy can mitigate ancestry-related risk of relapse.

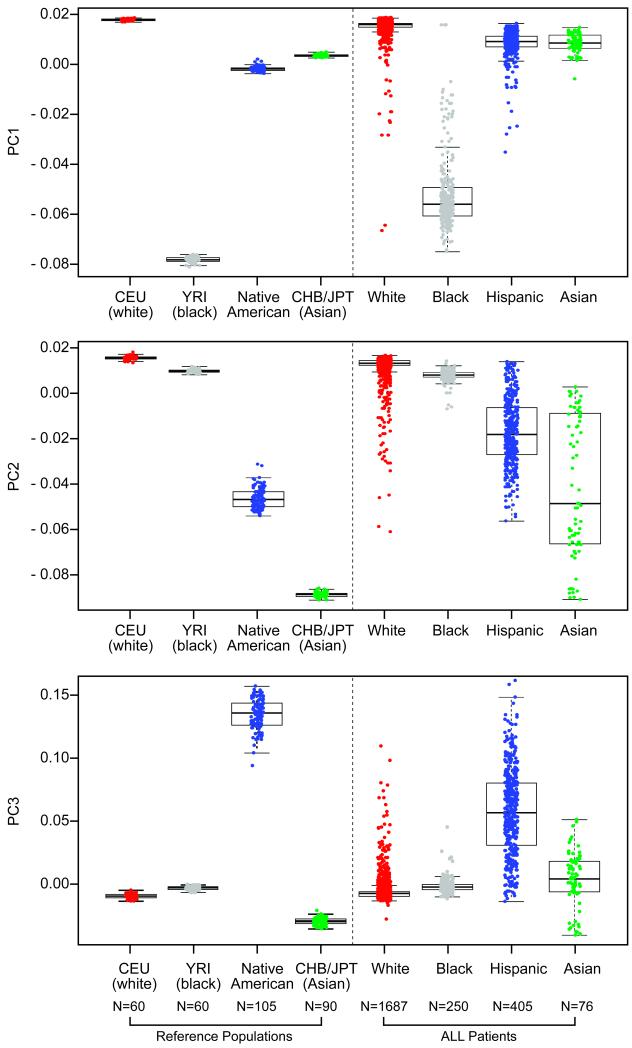

After applying quality control measures (Supplementary Note), we analyzed 444,044 germline genetic single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in an ethnically diverse group of 2,534 children with ALL. To summarize genetic variation, we applied principal component analysis (PCA) to genotypes of 2,849 individuals, including 2534 patients with ALL, plus 210 HapMap samples from descendants of Northern Europeans (CEU, N=60), West Africans (YRI, N=60), East Asians (CHB, N=45; JPT, N=45), and 105 Native American (NA)13 reference groups (Fig. 1). The top ranked principal component (PC1) separated self-reported black patients (N=250) and the YRI HapMap samples from all other groups (Fig. 1A); PC2 separated self-reported Asian patients (N=76) and the CHB/JPT HapMap samples from non-Asian populations (Fig. 1B). PC3 primarily captured genetic variation characteristic of NA ancestry, and self-reported Hispanics (N=405) exhibited a cline in PC3 between NA reference populations and other ancestral groups (Fig. 1C), consistent with the extensive ancestral admixture in Hispanics. Because the components of genomic variation (e.g. PCs) clearly co-segregated with geographic ancestries, we applied STRUCTURE14 to quantitatively determine ancestral composition of children with ALL. Patients encompassed a wide array of self-declared ethnic groups (Table 1) and we observed substantial variability in the ancestral genetic background of this unselected group of 2,534 children (Fig. 2A and Table 2).

Figure 1. Principal Component Analysis of Genome-wide Germline SNP Genotypes in Children with ALL.

Comparison of the top 3 axes of variation (PCs) among patients with ALL of different self-reported races/ethnicities and among different reference populations (CEU, N=60; YRI, N=60; CHB/JPT, N=90 samples from the HapMap and 105 Native American samples). Descriptions on X-axes represent self-declared designations. Boxes include data between the 25th and the 75th percentiles. Note that the first (PC1, Panel A), second (PC2, Panel B), and third axis (PC3, Panel C) reflect genetic variation characteristic of African, East Asian, and Native American ancestry, respectively. Also note that self-reported Asians consisted of both South Asians and East Asians (top and bottom cluster of far right bar in Panel B, respectively), with varying levels of East Asian genetic ancestry.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristicsa

| Characteristics | Clinical Trials | Native American A ncestry (average % ± standard deviation) |

P Value for Relation to Native American Ancestryc |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Jude Total Therapy XIIIB an d XV (N=707) |

COG P9906 (N=222) |

COG P9904/9905 (N=1,605) |

|||

| Self-reported race/ethnicityb | <0.0001 | ||||

| White | 493 (69.7) | 131 (59) | 1063 (66.2) | 1.4 ± 5.2 | |

| Black | 118 (16.7) | 15 (6.8) | 117 (7.3) | 0.9 ± 2.0 | |

| Hispanic | 67 (9.5) | 52 (23.4) | 286 (17.8) | 40.8 ± 20.6 | |

| Asian | 10 (1.4) | 10 (4.5) | 56 (3.5) | 2.9 ± 6.0 | |

| Others | 19 (2.7) | 14 (6.3) | 83 (5.2) | 15.5 ± 25.2 | |

|

| |||||

| Gender | 0.15 | ||||

| Male | 397 (56.2) | 150 (67.6) | 825 (51.4) | 7.7 ± 17.1 | |

| Female | 310 (43.8) | 72 (32.4) | 780 (48.6) | 9.0 ± 18.9 | |

|

| |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 0.17 | ||||

| <10 | 514 (72.7) | 76 (34.2) | 1407 (87.7) | 8.5 ± 18.8 | |

| ≥10 | 193 (27.3) | 146 (65.8) | 198 (12.3) | 7.7 ± 16.7 | |

|

| |||||

| Leukocyte count at diagnosis, /ul | 0.23 | ||||

| <50,000 | 527 (74.5) | 123 (55.4) | 1453 (90.5) | 8.0 ± 17.6 | |

| ≥50,000 | 180 (25.5) | 99 (44.6) | 152 (9.5) | 9.8 ± 19.4 | |

|

| |||||

| CNS statusd | 0.59 | ||||

| CNS1 | 485 (68.6) | 169 (76.1) | 1469 (91.5) | 8.8 ± 17.6 | |

| CNS2 | 164 (23.2) | 25 (11.3) | 135 (8.4) | 9.8 ± 19.6 | |

| CNS3 or traumatic puncture | 58 (8.2) | 28 (12.6) | 0 (0) | 9.9 ± 20.3 | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.43 | |

|

| |||||

| Lineage and molecular subtype of ALLe | 3×10−4e | ||||

| BCR-ABL | 14 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.7 ± 4.9 | |

| TCF3-PBX1 | 36 (5.1) | 24 (10.8) | 65 (4) | 12.4 ± 22.2 | |

| MLL rearrangements | 9 (1.3) | 20 (9) | 0 (0) | 10.3 ± 19.4 | |

| ETV6-RUNX1 | 127 (18) | 2 (0.9) | 454 (28.3) | 7.3 ± 16.9 | |

| T-cell | 109 (15.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3.6 ± 11.9 | |

| B-other | 412 (58.3) | 176 (79.3) | 1086 (67.7) | 8.7 ± 18.3 | |

|

| |||||

| DNA indexf | 0.25 | ||||

| <1.16 | 538 (76.1) | 204 (91.9) | 1055 (65.7) | 8.8 ± 17.9 | |

| ≥1.16 | 166 (23.5) | 14 (6.3) | 502 (31.3) | 7.7 ± 17.2 | |

| Missing | 3 (0.4) | 4 (1.8) | 48 (3) | 15.7 ± 25.2 | |

|

| |||||

| End-of-induction MRDg | 0.46 | ||||

| <0.01% | 477 (67.5) | 137 (61.7) | 1220 (76) | 8.3 ± 17.9 | |

| ≥0.01% & <1% | 102 (14.4) | 45 (20.3) | 226 (14.1) | 9.2± 19.2 | |

| ≥1% | 26 (3.7) | 21 (9.5) | 34 (2.1) | 11.5 ± 22.1 | |

| Missing | 102 (14.4) | 19 (8.6) | 125 (7.8) | 6.3 ± 14.6 | |

Abbreviations: MRD, minimal residual disease; CNS, central nervous system; COG, Children’s Oncology Group

Data are presented as number (%) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Self-reported race was assigned based on clinical trial databases, as described in Methods.

Associations with Native American ancestry (as a continuous variable) were assessed by Wilcoxon test for all features.

CNS status indicates the level of leukemia penetration into the CNS, and a higher grade (e.g., CNS3) is usually associated with poor prognosis.

A lower percentage of NA ancestry was noted in patients with BCR-ABL or T-cell ALL, likely because these subtypes were excluded from the COG studies and there were differing demographics between St. Jude and COG cohorts.

DNA index represents the ratio of DNA content of leukemia sample/diploid human normal control, an indicator of aneuploidy in tumor. DNA index of ≥1.16 is associated with hyperdiploidy of >50 chromosomes in ALL blasts.

MRD was determined at day 29 in COG and day 46 in St. Jude.

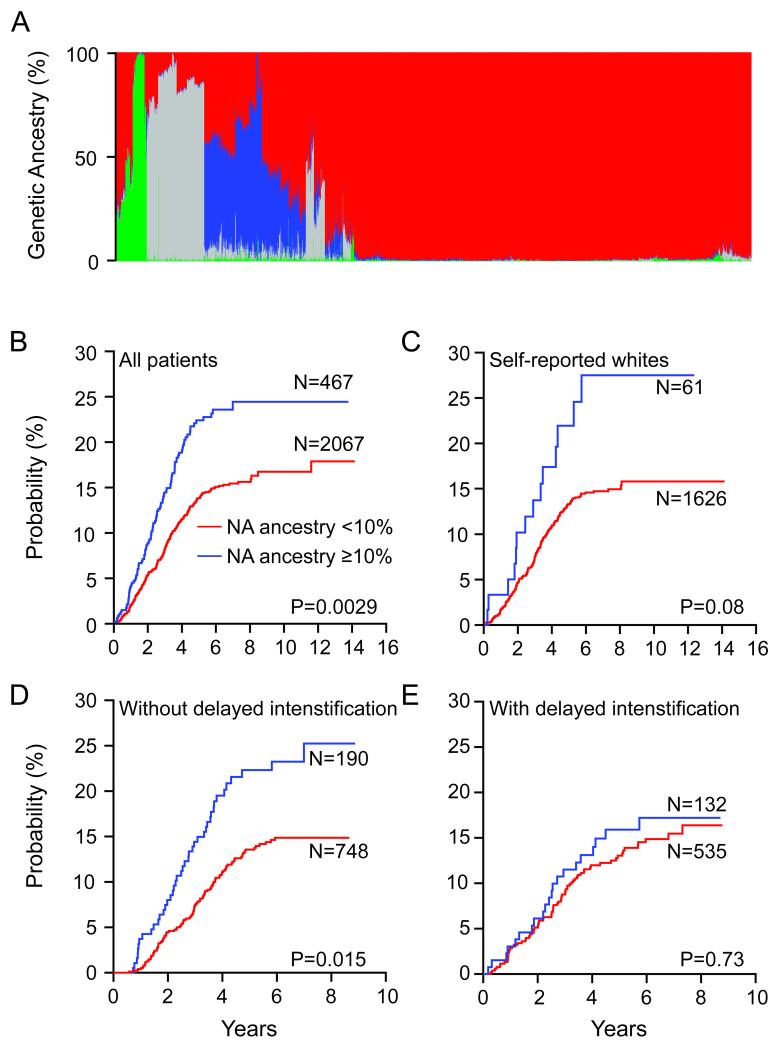

Figure 2. Genetic Ancestry and Risk of Relapse in Childhood ALL.

A. Genetic ancestral composition of 2,534 children with ALL. Each patient’s ancestry is depicted as a column, whereas color represents the proportion of ancestry estimated for that patient (European, red; African, gray; Asian, green; Native American [NA], blue). Genetic ancestry was estimated using STRUCTURE. Patients were clustered using Ward clustering method, based on dissimilarity in genetic ancestry measured by 1-minus pair-wise correlation (see Supplementary Note). Higher levels of NA ancestry were linked to increased risk of relapse in all patients (B), and within the self-reported whites (C), and for those who did not receive delayed intensification (D), but not within those who did receive delayed intensification in the COG P9904/9905 trial (E). Although cumulative incidence of relapse is plotted separately for patients with <10% (red) vs ≥10% (blue) NA ancestry, all P values were estimated using Fine and Gray’s cumulative incidence hazard regression model treating NA ancestry as a continuous variable (see Supplementary Note for details on NA ancestry dichotomization).

Table 2.

Average Genetic Ancestry by Self-reported Designations

| Genetic Ancestrya | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % European | % African | % Asian | % Native American | |

| Self-reported White (N =1,687) | 96.7% | 0.9% | 1.0% | 1.4% |

| Self-reported Black (N=250) | 19.3% | 79.0% | 0.8% | 0.9% |

| Self-reported Hispanic (N=405) | 51.6% | 6.1% | 1.5% | 40.8% |

| Self-reported Asian (N=76) | 32.3% | 1.0% | 63.8% | 2.9% |

| Other (N=116) | 55.8% | 9.4% | 19.3% | 15.5% |

Genetic ancestry was estimated using STRUCTURE, as described in Supplementary Note.

We tested whether genetic ancestry itself was associated with treatment outcome, after stratifying for treatment protocols, and found that the cumulative incidence of relapse was significantly associated with higher NA ancestry, treated as a continuous variable (Fig. 2B, P=0.0029, N=2,534, Supplementary Table S1). NA ancestry was also negatively associated with event-free survival (P=0.018). Within patients self-reporting as whites, there was a trend for higher NA ancestry to be related to a higher risk of ALL relapse (Fig. 2C, P=0.08, N=1,687). In a multivariate analysis adjusting for known risk factors for relapse (e.g. leukocyte count [≥ or <50,000/μl], age [≥ or <10 years], ALL lineage and molecular ALL subtypes [T or B-cell ALL, presence or absence of MLL rearrangements, ETV6-RUNX1, TCF3-PBX1, and BCR-ABL], DNA index [≥ or <1.16], and minimal residual disease [MRD, ≥ or <0.01%]), NA ancestry remained prognostic (P=0.017 when NA ancestry was treated as continuous variable [Table 3]). To dichotomize NA ancestry in a manner similar to the dichotomization used for other ALL prognostic features such as leukocyte count, we divided patients into those with low (<10%) vs high (≥ 10%) NA ancestry (see Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Note for details), and NA ancestry remained associated with relapse (P=3.6×10−4, Supplementary Table S2) in the context of other dichotomized prognostic features. The same multivariate analysis that include self-declared Hispanic ethnicity instead of NA ancestry also showed Hispanic ethnicity associated with relapse risk (P=3.4×10−3, Supplementary Table S2). Unfavorable clinical features were not associated with NA genetic ancestry (Table 1). An important clinical indicator of relapse risk in ALL is the early response to therapy, determined by the level of MRD at the end of remission induction therapy. Even within the group of patients with negative MRD status, higher NA genetic ancestry was linked to a higher risk of relapse (P=0.08 when NA ancestry was treated as a continuous variable, P=0.006 for dichotomous NA ancestry [≥ or <10%], N=1,834, Supplementary Fig. S2). This is of clinical relevance, in that identifying a subgroup of patients who may need more intensive therapy despite negative MRD (good response to initial therapy) would provide additional prognostic information.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis for Risk of ALL Relapse

| Patient Characteristics | P Valuea | Hazard Ratiob (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| MRD Positive | <×10−6 | 3.73 (2.98, 4.68) |

| Leukocyte count at diagnosis (≥50,000/ul) | 6.00×10−6 | 1.93 (1.45, 2.57) |

| DNA Index (≥1.16) | 2.58×10−4 | 0.59 (0.45, 0.79) |

| Native American ancestry | 0.017 | 1.84 (1.12, 3.04) |

| Age at diagnosis (≥10 years) | 0.010 | 1.39 (1.08, 1.78) |

| ETV6-RUNX1 c | 0.012 | 0.67 (0.49, 0.91) |

| T-cell lineagec | 0.146 | 0.67 (0.40, 1.15) |

| BCR-ABL c | 0.454 | 1.48 (0.53, 4.12) |

| TCF3-PBX1 c | 0.793 | 0.93 (0.53, 1.63) |

| MLL rearrangementsc | 0.935 | 0.96 (0.41, 2.25) |

Abbreviations: MRD: minimal residual disease; CI: confidence interval

Associations with risk of relapse (any relapse) were assessed using the Fine and Gray’s regression model.

Hazard ratio: the relative difference (increase or decrease) in risk of ALL relapse when the patient is positive for the clinical feature of interest (e.g., 1.84-fold increase in relapse risk for every 100% increase in NA ancestry).

Terms refer to cancer characteristics of the ALL cells that may have prognostic significance and are used to subdivide cases. All prognostic features are dichotomized for presence vs absence of the patient characteristic except for NA ancestry, which is treated as a continuous variable. Supplementary Table S2 includes identical multivariate analyses with dichotomized variables used for all variables, including ancestry.

Notably, the prognostic impact of NA ancestry varied dependent upon specific treatment regimens. In the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) P9904/P9905 study, patients were either randomized or non-randomly assigned to receive or not to receive a delayed intensification phase (i.e. an 8-week multi-agent treatment, Supplementary Table S3). Higher NA ancestry was associated with higher relapse risk in children who did not receive delayed intensification (P=0.015, N=938, Fig. 2D), but not in those who did receive this phase of therapy (P=0.73, N=667, Fig. 2E). Similar results were observed when NA ancestry was dichotomized as a prognostic feature (≥ or <10%): P=0.0016 for those who did not receive the delayed intensification and P=0.51 for those who received the delayed intensification.

Delayed intensification consists of 8 weeks of chemotherapy involving 7 widely-used anticancer drugs: dexamethasone, vincristine, daunorubicin, asparaginase, thioguanine, cyclophosphamide, and cytarabine. For patients at lower risk of relapse, there has been some controversy as to whether the increased intensity of this phase of therapy (and its attendant slightly increased risk of complications such as infection15) is worth the benefit of lower relapse rates, which have been observed in most but not all settings16-18. Delayed intensification is relatively well-tolerated; it has been associated with an extra 5 days of hospitalization for its attendant toxicity (out of a total of ~ 134 weeks of ALL therapy)19. Thus, the benefits of delayed intensification are likely to outweigh the costs among the subset of patients with ≥ 10% NA ancestry, exemplifying the importance and possibility of individualizing ALL therapy on the basis of genetic variation. Additional insights will be gained from clinical trials to examine the therapeutic efficacy of various phases of therapy (delayed intensification and other phases), set in the context of other therapeutic regimens, in patients with high versus low % NA ancestry.

To further illustrate the evidence for the association between ancestry and relapse, we examined local NA ancestry across the genome for association with ALL relapse, using admixture mapping20. Of 3,682 genomic segments with unique NA ancestry status, local NA ancestry at several loci was associated with relapse, with a locus at 2p25.3 (rs17039396) exhibiting the strongest association between local NA ancestry and relapse (nominal P=3.2×10−7, genome-wide threshold for significance is P=1.4×10−5 based on 3,682 independent loci tested, Supplementary Note and Supplementary Fig. S3). Likewise, admixture mapping using a previously published admixture map for US Hispanics13 also identified 2p25.3 as having genome-wide significance for association with relapse (nominal P =1.1×10−6, genome-wide threshold is P=2.4 × 10−5, Supplementary Fig. S3).

To explore the mechanisms by which ancestry may affect ALL relapse risk, we also examined which individual SNP genotypes were significantly associated with relapse risk, with the phenotype defined as “any” relapse (hematologic plus extramedullary) as well as more narrowly defined as the most common (and deadly) form of relapse, hematologic relapse. A SNP in PDE4B (rs6683977) was the highest-ranked SNP associated with hematologic relapse (P=2.2×10−6), and also associated with any relapse risk (Supplementary Fig. S4 and S5), and admixture mapping indicated that local NA ancestry at 1p32.2-31.3 that encompassed SNPs in PDE4B (including rs6683977) exhibited a significant association signal (P=3.2×10−6 for that locus, P value threshold for genome-wide significance=1.4×10−5, Supplementary Note and Supplementary Fig. S3). Interestingly, primary ALL cells expressing higher levels of PDE4B were also more resistant to prednisolone (Supplementary Fig. S6), indicating that PDE4B might play a role in glucocorticoid response in ALL.

The association we observed between genomically-defined NA ancestry and relapse is consistent with higher ALL relapse risk among Hispanics3-5. The high risk of relapse associated with NA ancestry was not explained by an association of NA ancestry with known ALL relapse risk factors (Tables 1 and 3). The association was similar when we confined the analysis to self-declared whites (Fig. 2C), which is consistent with a genetic (rather than cultural or environmental) basis for the elevated risk of leukemia relapse in Hispanics. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that environmental, sociocultural, or dietary differences that are associated with NA ancestry also or even primarily influenced relapse risk.

Although current risk classification schemes identify children with more aggressive ALL, a substantial portion of patients are not cured with contemporary chemotherapy, and a substantial portion of patients who ultimately relapse are considered at “low risk” for relapse or do not exhibit MRD21,22. For these reasons, it was interesting that NA ancestry identified a group of patients who benefited by the use of an extra phase of chemotherapy (delayed intensification, Fig. 2D and E), and there was a trend for prognostic importance of NA ancestry even within the group exhibiting negative MRD (Supplementary Fig. S2), indicating that germline genomic variation may add prognostic value to current ALL risk stratification schema.

There are likely many mechanisms by which ancestry-related germline polymorphisms could affect drug response: our data illustrate that ancestry-related genomic variation could affect the probability of cure in part by affecting drug resistance. However, all such outcomes (and therefore the identification of genetic prognostic features) are also dependent upon therapy. Our data illustrate that giving additional chemotherapy can overcome the negative prognostic impact conferred by a set of ancestry-related polymorphisms, and thereby mitigate ethnic disparities in outcome of childhood ALL.

Methods

Patients and treatment

Included in this study were all 2,534 children with newly diagnosed ALL treated on St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (St. Jude) Total Therapy XIIIB23 or XV (N=707)24, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) P9906 (N=222)22, or COG P9904/P9905 clinical trials (N=1,605)22 who had successfully-genotyped germline DNA (Supplementary Note). None of the children received any ALL treatment prior to enrollment on these clinical trials. The studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards and informed consent was obtained from the parents, guardians, or patients, as appropriate. Risk-directed treatment was described previously for St. Jude23,24 and COG22 trials (Supplementary Table S3). Minimal residual disease (MRD) was determined in bone marrow at the end of remission induction therapy22,25.

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Mapping 500K Array sets or the Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0; a subset of genotypes was validated using Illumina GoldenGate assays (see Supplementary Note). Genotypes were coded as 0, 1, 2 for AA, AB, BB genotypes. Genotype calling and quality control were performed as described26 (Supplementary Note). The final analyses included 444,044 SNPs in 2,534 patients.

Race/ethnicity and ancestry

Self-reported race/ethnicity was designated in mutually exclusive categories of white, black, Hispanic, or Asian based on criteria in place for the original clinical trials (Table 1). An individual designated as self-reported Hispanic was considered in the Hispanic race/ethnicity category regardless of his or her racial background (which was usually not noted). Remaining patients included Native American/Native Alaskans, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders, and individuals for whom race/ethnicity was not noted, or reported as “other.”

Population structure was determined using EIGENSTRAT27 and was compared with geographic ancestral reference populations (HapMap samples from descendants of Northern Europeans, West Africans, East Asians, and NA13). We also estimated ancestral composition using STRUCTURE14 (version 2.2.3) on the basis of the genotypes at 30,000 SNPs (Supplementary Note and Supplementary Table S4). European, African, Asian, and Native American genetic ancestries were assumed to sum to 100% in each patient.

Association between genetic variation and risk of relapse

Relapse was defined as bone marrow relapse and/or extramedullary relapse. Lineage switch, second malignancy, and death during remission were incorporated as competing events. We evaluated associations between genetic ancestries (as a continuous variable, with each ancestry varying from 0 to 100%) and the risk of relapse using the Fine and Gray’s regression model28 and stratifying by 9 risk-adapted treatment arms: St. Jude Total XIIIB low risk23, St. Jude Total XIIIB high risk23, St. Jude Total XV low risk24, St. Jude Total XV standard/high risk24, COG P9906, and COG P9904/9905 regimens A, B, C, and D (Supplementary Table S3)22. When noted, NA ancestry was also analyzed as a dichotomous variable (i.e. ≥ or < 10%). The basis of the dichotomization is described in detail in the Supplementary Note. A threshold of 10% was the antimode that discriminated 2 major modes in the US ALL population (Supplementary Fig. S1)29, and approximately the same 10% value maximally differentiated relapse risk (see Supplementary Note). In multivariate analyses, known risk factors (leukocyte count [≥ or <50,000/μl], age [≥ or <10 years], ALL lineage and molecular ALL subtypes [T-cell ALL, MLL rearrangements, ETV6-RUNX1, TCF3-PBX1, BCR-ABL, or other B-lineage ALL], DNA index [≥ or <1.16], and MRD [≥ or <0.01%]) were included together with genetic ancestries. When evaluating the association between genotypes at individual germline SNPs and the risk of relapse, we adjusted for treatment arms and also included genetic ancestry as covariates to account for population stratification (Supplementary Note).

Spearman rank correlation test was used to determine the relationships between MRD (classified as negative [<0.01%] or positive [≥0.01%]) and genetic variation (genetic ancestry or genotypes at individual SNPs), as previously described26.

Statistical and computational analyses were performed using S-Plus software, version 7.0 (Insightful Corp, Seattle, WA), R version 2.6.1 (www.r-project.org), and SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all patients and their parents who participated St. Jude and COG protocols included in this study, clinicians and research staff at St. Jude and COG institutions, and Dr. Jeannette Pullen from University Mississippi at Jackson for assistance in classification of patients with ALL. Genome-wide genotyping of COG P9904/9905 samples was performed by the Center for Molecular Medicine with generous financial support from the Jeffrey Pride Foundation and the National Childhood Cancer Foundation. Steve P. Hunger is the Ergen Family Chair in Pediatric Cancer and Jun. J. Yang is supported by the American Society of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics Young Investigator Award and Alex Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer Young Investigator Grant. We also thank Dr. Mark Shriver at the Pennsylvania State University for sharing SNP genotype data of the Native American references. We are especially inspired by Damon Ingersoll, who bravely fought but lost his battle with ALL. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers: CA093552, CA78224, CA21765, R37CA36401, CA98543, CA114766, RC4CA156449, U10CA98413, U01GM 61393, and U01GM 92666], ALSAC, and by CureSearch.

Footnotes

Author Contribution Study concept and design: J.J.Y, C.C. and M.V.R; Acquisition of data: D.C., C-H.P., W.P.B., P.L.M., N.J.W., C.L.W, M.J.B., M.V.R., G.N., Y.F., M.D., B.M.C., and A.C.; Drafting of the manuscript: J.J.Y. and M.V.R.; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J.J.Y., C.C., W.Y., W.E.E., C-H.P., B.M.C., M.J.B., W.L.C., S.P.H., G.H.R., M.L., Y.F., M.V.R.; Statistical analysis: C.C., W.Y., X.C., M.D., N.J.C., and P.S.; Obtaining funding: G.H.R., D.C., W.E.E., M.B., W.L.C., S.P.H. and M.V.R.; Study supervision: M.V.R.

Competing Interests and Financial Disclosures The authors do not have any relevant competing interests to disclaim and full disclosures are provided in the Supplementary Note.

References

- 1.Pui CH, Evans WE. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N.Engl.J.Med. 2006;354:166–178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll WL. Race and outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2003;290:2061–2063. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadan-Lottick NS, Ness KK, Bhatia S, Gurney JG. Survival variability by race and ethnicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2003;290:2008–2014. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia S, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in survival of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1957–1964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollock BH, et al. Racial differences in the survival of childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. J.Clin.Oncol. 2000;18:813–823. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pui CH, et al. Results of therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in black and white children. JAMA. 2003;290:2001–2007. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hord MH, Smith TL, Culbert SJ, Frankel LS, Pinkel DP. Ethnicity and cure rates of Texas children with acute lymphoid leukemia. Cancer. 1996;77:563–569. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960201)77:3<563::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stiller CA, Bunch KJ, Lewis IJ. Ethnic group and survival from childhood cancer: report from the UK Children’s Cancer Study Group. Br.J.Cancer. 2000;82:1339–1343. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell JE, Mendez E, Parkes SE, Mann JR. Factors affecting survival in White and Asian children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br.J.Cancer. 2000;82:1568–1570. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pui CH, et al. Outcome of treatment for childhood cancer in black as compared with white children. The St Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience, 1962 through 1992. JAMA. 1995;273:633–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foucar K, et al. Survival of children and adolescents with acute lymphoid leukemia. A study of American Indians and Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites treated in New Mexico (1969 to 1986) Cancer. 1991;67:2125–2130. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910415)67:8<2125::aid-cncr2820670820>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatia S. Influence of race and socioeconomic status on outcome of children treated for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr.Opin.Pediatr. 2004;16:9–14. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao X, et al. A genomewide admixture mapping panel for Hispanic/Latino populations. Am.J.Hum.Genet. 2007;80:1171–1178. doi: 10.1086/518564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–59. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaynon PS, et al. Modified BFM therapy for children with previously untreated acute lymphoblastic leukemia and unfavorable prognostic features. Report of Children’s Cancer Study Group Study CCG-193P. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1988;10:42–50. doi: 10.1097/00043426-198821000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tubergen DG, et al. Improved outcome with delayed intensification for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and intermediate presenting features: a Childrens Cancer Group phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:527–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lange BJ, et al. Double-delayed intensification improves event-free survival for children with intermediate-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Blood. 2002;99:825–33. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchinson RJ, et al. Intensification of therapy for children with lower-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: long-term follow-up of patients treated on Children’s Cancer Group Trial 1881. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1790–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaynon PS, et al. Duration of hospitalization as a measure of cost on Children’s Cancer Group acute lymphoblastic leukemia studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1916–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.7.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sankararaman S, Sridhar S, Kimmel G, Halperin E. Estimating local ancestry in admixed populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schrappe M, et al. Improved outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia despite reduced use of anthracyclines and cranial radiotherapy: results of trial ALL-BFM 90. German-Austrian-Swiss ALL-BFM Study Group. Blood. 2000;95:3310–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borowitz MJ, et al. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and its relationship to other prognostic factors: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2008;111:5477–5485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pui CH, et al. Improved outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of Total Therapy Study XIIIB at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Blood. 2004;104:2690–2696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pui CH, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2730–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coustan-Smith E, et al. Clinical importance of minimal residual disease in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2000;96:2691–2696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang JJ, et al. Genome-wide interrogation of germline genetic variation associated with treatment response in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA. 2009;301:393–403. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat.Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeung KY, Fraley C, Murua A, Raftery AE, Ruzzo WL. Model-based clustering and data transformations for gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:977–987. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.10.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.