Abstract

The yeast Kodamaea (Pichia) ohmeri is a rare human pathogen with infrequent report of neonatal infection. Native valve endocarditis by Kodamaea ohmeri is extremely rare. The current case report describes a case of fatal nosocomial native valve endocarditis without any structural heart defects in a 40dayold baby. The patient was referred to our institute after having ICU stay of 18 days in another hospital for necrotizing enterocolitis and was found to have obstructive tricuspid valve mass and fungemia with Kodamaea ohmeri. In spite of the treatment, patient developed sepsis with disseminated intravascular coagulation and could not be revived.

Keywords: Endocarditis, Kodamaea ohmeri, fungal infection, native IE

INTRODUCTION

Infective endocarditis is an inflammatory and proliferative disease of the endocardium that affects mainly the valves.[1] Fungal etiology is relatively uncommon and is associated with high mortality especially if it is not treated early. It usually occurs in the presence of predisposing factors like immunocompromised state, use of endovascular devices, and previous reconstructive cardiac surgery.[2] Most common fungal species causing infective endocarditis are Candida and Aspergillus, and they are usually associated with bulky vegetation.

Kodamaea ohmeri is ascosporogenic yeast, formerly classified in the genus Pichia. The genus Kodamaea currently comprises five species: K. anthrophila, K. kakaduensis, K. laetipori, K. nitidulidarum, and K. ohmeri.[3] The latter one is pathogenic to plants and is used in food industry for fermentation.[4] It rarely causes infections in human beings also. Till date, only 20 cases were reported in the literature out of which only 3 were neonates and only 1 was a native valve endocarditis.

We report a 40-day-old neonate with nosocomial native valve endocarditis due to K. ohmeri.

CASE REPORT

A 40-day-old male baby, one among the twins, born of normal vaginal delivery at the 36th week of gestation, was referred to our institute for the management of tricuspid valve mass. Twenty days prior to that, the baby was admitted in a neonatal intensive care unit of another tertiary care hospital for evaluation and management of neonatal seizures and necrotizing enterocolitis. Blood cultures done there were negative. Baby was managed there with anti-convulsants and intravenous antibiotics, which included piperacillin tazobactam combination along with amikacin for necrotizing enterocolitis through peripheral venous access. No invasive procedures were done there during the stay. Echocardiography done there to rule out any structural heart disease revealed a tricuspid mass and was referred to our centre for further management.

On admission baby was not febrile but deeply icteric. There were no focal neurologic deficits or clinical heart failure. Clinical cardiovascular examination was normal. There was a small cephalhematoma of size 3 × 2 cm over the scalp. Computed tomography brain scan showed small petechial hemorrhages, but no space occupying lesions.

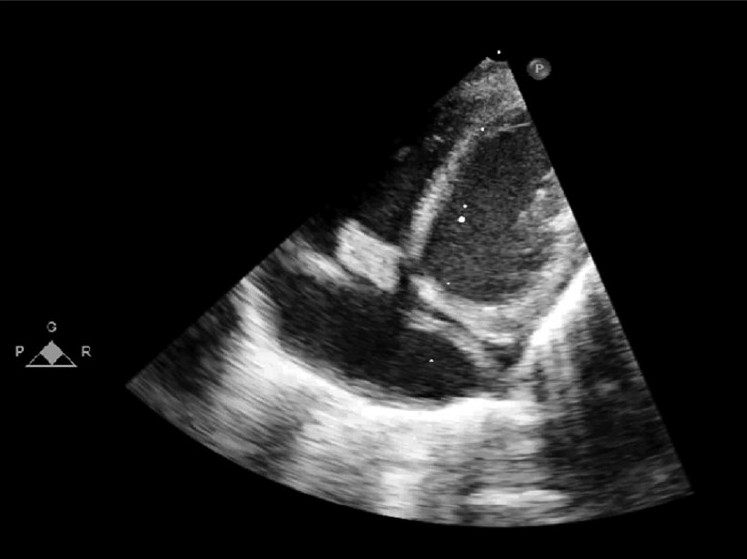

Echocardiography showed 11.1 × 6.4 mm vegetation attached to the tricuspid valve and Doppler examination showed a mean tricuspid inflow gradient of 5 mmHg [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Subcostal view showing vegetation attached to the native tricuspid valve, causing RV inflow obstruction. Also shown the coronary sinus draining into right atrium

Under sterile precautions, four blood cultures were collected from different sites on two consecutive days. All four blood cultures were positive by the BacT Alert 240-bioMerieux Marcy l’Etiole system (France) and the fungal cultures grew white yeast-like colonies. The organism was identified as K. ohmeri by using the card type “YST” on the Vitek 2 compact system (bioMerieux). Gram staining showed oval budding yeast cells. Antifungal susceptibility test was done by tube dilution method, following the standard method of NCCLS M38A. MIC of the anti-fungal agents were Amphotericin <0.25 mcg/L, Fluconazole 2 mcg/L, Voriconazole <0.12 mcg/L, and Flucytosine <1mcg/L. Results showed that the organism was susceptible to the available anti-fungal agents.

The baby was started on intravenous amphotericin B at the dose of 1 mg/day and other supportive measures including packed cell transfusion and was planned for surgical removal of the mass after a few days of antifungal therapy. However, the baby abruptly developed hemodynamic compromise on the second day after initiation of antifungal therapy due to fungal septicemia and could not be resuscitated.

DISCUSSION

Fungal endocarditis remains a rare infection. However, with the extensive use of intravenous antibiotics and many interventional procedures the incidence of fungal infections are on the rise.[5] To complicate the issue, many less common pathogenic organisms are also involved in serious infections. One such culprit is this fungus K. ohmeri, which is a very rare human pathogen, with only 20 cases reported in the literature, so far. Even rare is the native valve endocarditis due to this organism.

Fungi are classified primarily based on the structures associated with sexual reproduction, which tend to be evolutionarily conserved. However, many fungi reproduce only asexually, and cannot be easily placed in a classification based on sexual characters; some produce both asexual and sexual states. These problematic species are often members of the Ascomycota, but may also belong to the Basidiomycota. At present, the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature permits mycologists to give asexually reproducing fungi (anamorphs) separate names from their sexual states (teleomorphs).

K. ohmeri is ascosporogenic yeast that usually occurs in the haploid state. It belongs to a genus of ascosporogenous yeasts from the Saccharomycetaceae family. It is the teleomorph of Candida guilliermondii var. membranaefaciens. Ascospores are the globose spores found in the sexual state and may number 4-8 in one ascus. They stain gram negative, while vegetative candida are gram positive. The species has also been isolated from various substrates such as dates, sambal ulak, gooseberry jelly, brines with various concentrations of salt and lactic acid, torani, salted cucumbers, rotten mushroom, and seawater.[6]

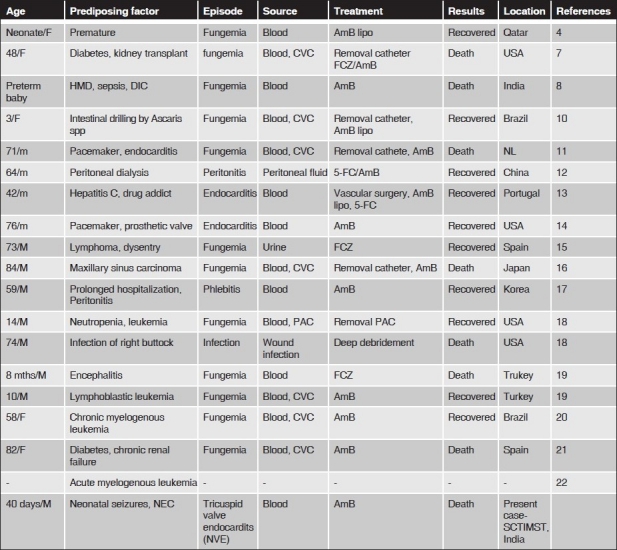

Cases so far reported [Figure 2] are from immunocompromised hosts with presence of invasive devices. It was first isolated in a 48 year old, diabetic, female patient.[7] In India, this is the second case, other case being a preterm baby with hyaline membrane disease.[8] K. ohmeri infection responds to the removal of the devices, catheter, etc., as it is mostly associated with invasive devices, Out of the three neonatal infections described so far, one responded to the removal of the catheter without antifungal treatment,[9] one responded to liposomal amphotericin-B, and the other baby succumbed to disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Figure 2.

Cases so far reported worldwide. Only 20 cases reported so far largely due to under recognition of this potentially treatable organism

All time reported cases are summarized in Figure 2.[10–22]

Lee et al studied the susceptibility of K. ohmeri to various antifungal agents.[9] In this study all of the isolates of K. ohmeri were susceptible to amphotericin, with low susceptibility to fluconazole and itraconazole, some isolates showing dose-dependent response. A consensus is developing today that most neonates treated with amphotericin-B have more positive outcomes and that thrombocytopenia or transient renal and hepatic abnormalities are more likely related to the systemic infection or other persisting problems than to amphotericin-B toxicity. Generally, fever, nausea, and vomiting are less common in infants than adults and may tolerate amphotericin-B well.[23]

Liposomal amphotericin is better than conventional preparation because of its safety profile. There is also increasing evidence to suggest that it may be more efficient in eradicating severe fungal infections in neonates.[24]

In our patient, the immunocompromised status of the preterm infant with high dependence state in the hospital and multiple intravenous injections and the hospital environment have contributed to the pathogenesis of the infection.

To conclude, infections caused by these rare organisms are identified more frequently. It occurs in a broad range of patient categories including children and newborn (our present case). But the actual incidence is difficult to estimate because of unawareness of this rare species. Since this pathogen readily responds to early removal of the infected catheter or other source of infection, early diagnosis could save the life of the patients especially in the immunocompromised and newborn.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the support given by Dr Kavita Raja, Professor and Head of the department, Department of Microbiology, SCTIMST.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Joao L, Duarte J, Cotrim C, Rodrigues A, Martins C, Fazendas P, et al. Native valve endocarditis due to Pichia ohmeri. Heart Vessels. 2002;16:260–3. doi: 10.1007/s003800200034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anaissie EJ, Bodey GP, Rinaldi MG. Emerging fungal pathogens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:323–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01963467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fungal Databases Nomenclature and Species Banks Online Taxonomic Novelties Submission. Utrecht, Netherland: c2004. MycoBank; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taj-Aldeen SJ, Doiphode SH, Han XY. Kodamaea (Pichia) ohmeri fungaemia in a premature neonate. J Med Micorobiol. 2006;55:237–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patted SV, Halkati PC, Yavagal ST, Patil R. Candida Krusei infection presenting as a right ventricular mass in a two month old infant. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;2:170–2. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.58324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Centralbureau Voor Schimmelcultures (CBS) Yeasts Database. Utrecht, Netherland: CBS Fungal Biodiversity Centre; c2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergman MM, Gagnon D, Doern GV. Pichia ohmeri fungemia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:229–31. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poojary A, Sapre G. Kodamaea ohmeri Infection in a Neonate. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:629–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JS, Shin JH, Kim MN, Jung SI, Park KH, Cho D, et al. Kodamaea ohmeri isolates from patients in a University Hospital: Identification, antifungal susceptibility and pulsed field gel electrophoresis analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1005–10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02264-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Barros JD, Do Nascimento SM, De Araújo FJ, Braz Rde F, Andrade VS, Theelen B, et al. Kodamaea (Pichia) ohmeri fungemia in a pediatric patient admitted in a public hospital. Med Mycol. 2009;47:775–9. doi: 10.3109/13693780902980467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matute AJ, Visser MR, Lipovsky M, Schuitemaker FJ, Hoepelman AI, et al. A case of disseminated infection with Pichia ohmeri. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:971–3. doi: 10.1007/s100960000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choy BY, Wong SS, Chan TM, Lai KN. Pichia ohmeri peritonitis in a patient on CAPD: Response to treatment with amphtericin. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20:91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.João I, Duarte J, Cotrim C, Rodrigues A, Martins C, Fazendas P, et al. Native valve endocarditis due to Pichia ohmeri. Heart Vessels. 2002;16:260–3. doi: 10.1007/s003800200034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reina JP, Larone DH, Sabetta JR, Krieger KK, Hartman BJ, et al. Pichia ohmeri prosthetic valve endocarditis and review of literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:140–1. doi: 10.1080/00365540110080142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puerto JL, García-Martos P, Saldarreaga A, Ruiz-Aragón J, García-Agudo R, Aoufi S, et al. First report of urinary tract infection due to Pichia ohmeri. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21:630–1. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hitomi S, Kumao T, Onizawa K, Miyajima Y, Wakatsuki T, et al. A case of central-venous-catheter-associated infection caused by Pichia ohmeri. J Hosp Infect. 2002;51:75–7. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin DH, Park JH, Shin JH, Suh SP, Ryang DW, Kim SJ, et al. Pichia ohmeri fungemia associated with phlebitis: Successful treatment with amphotericin B. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:88–9. doi: 10.1007/s10156-002-0208-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han XY, Tarrand JJ, Escudero E. Infections by the yeast Kodamaea (Pichia) ohmeri: Two cases and literature review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:127–30. doi: 10.1007/s10096-003-1067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otag F, Kuyucu N, Erturan Z, Sen S, Emekdas G, Sugita T, et al. An outbreak of Pichia ohmeri infection in the paediatric intensive care unit: Case reports and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2005;48:265–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2005.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostronoff F, Ostronoff M, Calixto R, Domingues MC, Souto Maior AP, Sucupira A, et al. Pichia ohmeri fungemia in a hematologic patient: An emerging human pathogen. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1949–51. doi: 10.1080/10428190600679031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Tapia A, García-Agudo R, Marín P, Conejo JL, García-Martos P, et al. Kodamaea ohmeri fungemia associated with surgery. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2007;24:155–6. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1406(07)70033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahfouz RA, Otrock ZK, Mehawej H, Farhat F. Kodamaea (Pichia) ohmeri fungaemia complicating acute myeloid leukaemia in a patient with hemochromatosis. Pathol. 2008;40:99–101. doi: 10.1080/00313020701716268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingo AR, Smyth JA, Waisman D. Lack of evidence of amphotericin B toxicity in very low birth infants treated for systemic candidiasis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:1002–3. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199710000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knoppert D, Salama HE, Lee DS. Eradication of severe neonatal systemic candidiasis with amphotericin B lipid complex. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1032–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]