Abstract

A microbiological algorithm has been developed to analyze beach water samples for the determination of viable colony forming units (CFU) of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). Membrane filtration enumeration of S. aureus from recreational beach waters using the chromogenic media CHROMagar™SA alone yields a positive predictive value (PPV) of 70%. Presumptive CHROMagar™SA colonies were confirmed as S. aureus by 24-hour tube coagulase test. Combined, these two tests yield a PPV of 100%. This algorithm enables accurate quantitation of S. aureus in seawater in 72 hours and could support risk-prediction processes for recreational waters. A more rapid protocol, utilizing a 4-hour tube coagulase confirmatory test, enables a 48-hour turnaround time with a modest false negative rate of less than 10%.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) has been reported in recreational beach waters1–6 and been discussed as a potential hazard in swimming pools.7 The growing clinical and public health concern regarding increasing community acquired methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection rates8,9 makes identification and perhaps quantitation from environmental sources a timely issue. Seawater, and seawater spiked with S. aureus innocula, were used in pilot studies to assess the possibility of adapting existing methods for the quantitation of S. aureus in seawater. A number of new products are available for the detection of S. aureus, based upon microbiological or molecular methods. Bio-Rad's MRSA Select (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) chromogenic media plate is specific for MRSA, and demonstrated reduced specificity when challenged with the offlabel mixed population of halophiles of our ocean water samples. Petrifilm Staph Express Disk (3M Microbiology, St. Paul, MN), tube culture10 and modified mannitol salt plating methods3,11,12 yielded poor specificity from seawater (data not shown), and/or detection levels significantly higher than levels expected from recreational beach water (data not shown).5, 13 Methods based upon modified Baird-Parker media5, 12 yield insufficient selectivity and unknown sensitivity3 (data not shown).

Commercial molecular detection products do not provide quantitative measures of contamination because an intermediate biological amplification step is required, but they do provide an answer as to the presence of S. aureus in the sample. For example, the PCR-based TaqMan Staphylococcus aureus Detection Kit (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), developed for detection of S. aureus in the food industry, yielded variable and unreliable results in off-label pilot studies to detect and quantitate low levels of S. aureus in beach water (data not shown). Interpretation of gene-based quantitative results is complicated by concerns related to viable organisms and the amount of free or apoptotic DNA contained in the environmental sample.

The ability to reliably quantify the number of S. aureus organisms in recreational water is necessary for the development of risk models and potential water quality monitoring. This study examines the reliability of the chromogenic media CHROMagar™SA (CSA), developed for clinical application, to quantify viable colony forming units (CFU) of S. aureus in seawater.

Materials and Methods

Determination of Filter Efficiency: Filtered and autoclaved seawater or 0.9% saline were spiked with log-phase MRSA (ATCC 25923) or methicillin sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) (NCTC 8325) to 103CFU/mL and processed to determine the efficiency of filter capture and the effects of dilution or media on S. aureus viability. Filter efficiency compared 100µL samples that were either i) applied directly to a plate and spread or ii) diluted to 20mL, filtered, then the filter applied to the plate. Dilutions were made with either sterile seawater or 0.9% saline. Samples were placed either on CSA (CHROMagar™SA, BD BBL 214982, BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) or SBAP (TSA II with 5% Sheep Blood, BD BBL 221261, BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) plates. Twenty-four (24) replicates were recorded for each condition. One-Way ANOVA was performed using JMP-IN (SAS, Inc.). Positive values for the all-pairs Tukey-Kramer HSD matrix indicate slight yet statistically significant differences between the compared means of the CFU determinations.

Environmental sample collection and candidate colony development: Seawater samples from active recreational beaches were collected by hand immersion of 500mL autoclaved wide-mouth bottles with screw caps to sufficient depth to completely cover the opening of the bottle.14 Collection occurred at 6 sites for 15 days over the course of a month, from the surface of beach waters with a water column of approximately 50cm. Filled bottles were placed on ice and processed within four hours of sample collection. A 20mL aliquot of seawater was filtered on a vacuum manifold through a 47mm 0.45 micron mixed cellulose ester gridded white filter (Advantec A045H047A, Advantec MFS, Inc., Dublin, CA, USA) using autoclaved polysulfone filter holders. The filter was applied face up on a CHROMagar™SA plate and incubated at 35C for 24 hours.

For the purpose of this experiment, all mauve colonies and others with closely related colors (mauve-like) were chosen for secondary plating. An additional 10% of colonies with other colors were also selected for secondary plating on CSA to assure the color screen was not over-selective.

Tests to Confirm Algorithm: Candidate colonies were scored as S. aureus if they showed a microscopic morphology of gram positive cocci in clusters and yielded a positive 24-hour tube coagulase test (BD BBL Coagulase Plasma, Rabbit with EDTA, BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Candidate colonies were also tested for latex agglutination (SLIDEX Staph-Kit, Biomerieux, Inc., Durham, N.C., USA). The latex agglutination test was a parallel confirmatory test. Our intent was to evaluate the relative performances of coagulase and agglutination tests (Table 2). 174 candidate isolates from filters plated on CHROMAgar SA were tested for confirmation as S. aureus by i) the presence of clumping factor and/or protein A by the SLIDEX latex agglutination test, or ii) the presence of coagulase activity determined by tube coagulase test. Isolates yielding positive SLIDEX results were contemporaneously tested for agglutination activity with the latex bead. Those isolates yielding positive results for both anti-Staphylococcus aureus reagent and the negative control reagent (+/+) were counted as uninterpretable. Tube coagulase assays were read following 4- and 24-hours of incubation at 37C.

Table 2.

Confirmatory Tests of Isolates from CHROMagar™ SA

| SLIDEX | S. aureus | NOT S. aureus |

| positive (+/−) | 57 | 1 |

| negative (−/0) | 0 | 83 |

| uninterpretable (+/+) | 6 | 27 |

| tube coagulase | S. aureus | NOT S. aureus |

| 4-hr. positive | 57 | 2 |

| 24-hr. positive | 63 | 2 |

| 24-hr. negative | 0 | 109 |

Strains ATCC 25923 and NCTC 8325 were used as species phenotype controls for S. aureus, but not included in the statistical analysis. Species identification was confirmed by biogram (VITEK 2, Biomerieux, Inc., Durham, N.C., USA) or by rDNA sequencing.15 Statistical analyses were carried out with the JMP-IN (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) platform.

Results

Filter Recovery Efficiency and Media Viability: Table 1 details the results of the filter recovery study. The two initial log-phase cultures (MRSA and MSSA) were of slightly differing concentrations, as evidenced by the mean CFU observed for the MRSA samples versus the MSSA mean CFU. A ratio of means near unity and a small R-squared value from the ANOVA (testing the hypothesis that the paired means are identical) indicates no statistical difference in viability of either reference strain on CSA compared to SBAP media. There may be a slight increase for the MRSA strain viability when diluted in saline compared to seawater. No such preference was observed with the MSSA strain. The number of viable CFU enumerated from filtered samples was greater, and more reproducible (smaller coefficient of variation), than those counted from spread plates. These conclusions are corroborated by the relevant occurrence of positive values in the Tukey-Kramer HSD matrices (Table 1).

Table 1.

Capture Efficiency of S. aureus by filtration

| MRSA | mean CFU | C.V. | ratio of means | R-Squared | Tukey-Kramer HSD | |

| Spread | 35.9 | 27.6 | −5.30 | 6.92* | ||

| Filter | 47.7 | 7.6 | 0.75 | 0.369 | 6.92* | −4.60 |

| Seawater | 37.8 | 24.8 | 0.46 | −5.86 | ||

| Saline | 44.1 | 21.2 | 0.86 | 0.106 | −5.86 | 0.46 |

| CSA | 42.6 | 23.5 | −5.67 | −2.20 | ||

| SBAP | 38.7 | 24.0 | 1.10 | 0.040 | −2.20 | −6.55 |

| MSSA | mean CFU | C.V. | ratio of means | R-Squared | Tukey-Kramer HSD | |

| Spread | 18.0 | 37.8 | −3.45 | 0.13 | ||

| Filter | 21.6 | 22.8 | 0.83 | 0.087 | 0.13 | −3.45 |

| Seawater | 19.7 | 29.9 | −3.55 | −3.60 | ||

| Saline | 19.8 | 32.8 | 0.99 | 0.001 | −3.60 | −3.55 |

| CSA | 18.7 | 35.8 | −1.42 | −3.55 | ||

| SBAP | 20.9 | 25.8 | 0.90 | 0.031 | −3.55 | −1.42 |

Viable S. aureus colony forming units (CFU) were counted from spiked solutions and treated variously to determine recovery efficiency. Paired comparators included spread on plate vs. filtered, diluted in sterile seawater vs. 0.9% saline, and growth on media of CHROMagar™ SA (CSA) vs. TSA-II + 5% Sheep Blood (SBAP). C.V. = coefficient of variation; MRSA = methicillin resistant S. aureus; MSSA = methicillin sensitive S. aureus.

CHROMagar™SA detection of candidate S. aureus colonies: BBL CHROMagar™SA (CSA) is intended for the identification and isolation of S. aureus based upon the development of mauve-colored colonies. The chromogenic CSA media developed color in the colonies that grew on top of the filter, although color could be visualized on the underside of the filter as well.

24 hours growth of the filtered seawater sample filter on a CSA plate was followed by a secondary CSA plate used to further develop candidate colonies for confirmation as S. aureus. 48 hours growth on the filter/primary CSA plate yielded significant overgrowth of colonies and color drift. For example, some mauve colonies became brown on the top surface yet retained a mauve tone when viewed from the underside of the filter.

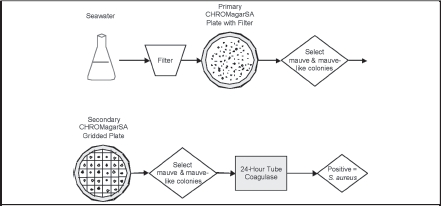

613 candidate colonies from the filter/primary CSA plates of 90 environmental sampling events from recreational beaches were selected and transferred to secondary CSA plates in a 25-place grid format (Figure 1). Eighty-eight (88) mauve and 86 additional mauve-like candidate colonies from the secondary plate were subjected to further species-confirming tests, described below. The secondary colonies were mixed colonies in about 10%, as evidenced by Gram stain reaction, color, and morphology on the CSA plate. Further isolation to single colony isolates was not performed.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for Identification of S. aureus by CHROMagar™ SA and Tube Coagulase

Colonies are picked from a filter placed on CSA, then gridded to a secondary CSA plate. Mauve-like (including mauve) candidate colonies are subjected to confirmatory testing by tube coagulase. The gram-stained microscopy and species confirmation discussed in the text were methodological validation tests, and are not considered part of the quantitative algorithm.

Tube Coagulase Test: A 4-hour coagulase test yielded 6 fewer positive results than the 24-hour reading (Table 2). Of 233 candidate colonies tested, 6 colonies (4 mauve and 2 light purple) yielded negative 4-hr coagulase test results but were positive after 24hr incubation and were subsequently deemed S. aureus. All 6 were SLIDEX-positive. Two colonies were false–positive for the coagulase, had brownish tone on CSA, gram positive (g+) large cocci tetrads, and were SLIDEX-negative.

SLIDEX Staph-Kit Test (agglutination from clumping factor or protein A or species-specific modified surface proteins): 174 mauve and mauve-like secondary colonies were tested, with one false-positive reaction from a purple colony that yielded a negative coagulase result. 33 colonies (including 6 mauve) yielded uninterpretable (+ / +) results; (i.e. the latex control and reagent both yielded positive results).

Gram Stain: Microscopic color and morphology of Gram-stained isolates were evaluated on 92 colonies from the secondary plates, including all colonies that yielded a positive result for either the tube coagulase or SLIDEX test, and a subset of 25 other colonies. All colonies deemed S. aureus were gram positive (g+) cocci clusters. Eight S. aureus colonies were mixed populations, and were either mauve (6) or mauve with white spots (2) on the secondary plate colony. The 5 non-S. aureus mauve colonies tested by gram stain were either g+ cocci clusters (2) or large g+ cocci tetrads (3).

Species Confirmation: Six randomly selected putative S. aureus colonies (6/58 colonies), as defined by mauve colony and positive coagulase test, were confirmed as S. aureus by sequencing the 16S rDNA. VITEK 2 biograms were performed to identify species of other classes of results. A random 10% (3 of 25 colonies) of the false color-positive colonies (mauve colonies that failed gram stain, SLIDEX, and coagulase tests) were identified as alpha-hemolytic streptococci (1) and S. caprae (2). All five false color-negative colonies (i.e. were mauve-like in color, but not mauve, and were g+ and coagulase positive) were identified as S. aureus. Alternatively, a random 8 of the 86 mauve-like but not mauve colonies that yielded negative coagulase test results were variously identified as Kokuria sp. (6 colonies), and gram negative undetermined (2 colonies).

Discussion

Bacteria dominate the abundance and diversity of the ocean (Reviews16,17). One microliter of seawater is considered to contain 1,000 bacteria, and 100 other individual cells.18 It is therefore a challenge to selectively detect and enumerate a particular genus in volume of seawater; this challenge is even greater for an individual species. The species heterogeneity of beachwater samples prevented the reliable use of traditional clinical microbiologic screens with selective media like mannitol salt agar. The advent of chromogenic media specific for S. aureus obtained from clinical samples lead us to consider the use of CHROMagar™SA for enumeration of viable S. aureus in recreational beach waters, even though a large background of non-S. aureus growth was expected. This is a report of an inexpensive reliable methodology for the enumeration of S. aureus in sea water that does not rely on molecular biology techniques requiring expensive capital equipment and reagents.

High capture efficiency and good growth characteristics of viable S. aureus are observed on 0.45µM filters, indicating a high sensitivity of the methodology. The pore size is sufficiently small to yield good filter retention; apparently S. aureus does not shrink in these solutions, contrary to concerns expressed for chlorine-treated waters (Health Protection Agency, 2004). The principle limits to sensitivity are the volume of sampled water to be filtered and the growth of non-S. aureus colonies on the primary filter that mask the selective color formation of the CSA media. The practical limit of detection by this technique is estimated to be on the order of 1 CFU of S. aureus/100mL of seawater. A larger volume of filtrate results in excessive numbers of non-mauve colonies that make recognition of mauve colonies unreliable. This limit of detection may vary, depending upon the non-S. aureus load of the samples waters.

In controlled experiments, elevated CFU counts from filtered samples were observed relative to spread plates. This result has been previously reported19, 20 and might be explained by greater clumping of the coccal clusters in the spread samples. This accents the uncertainty of how many individual bacteria are contained in a CFU. An open question is whether a risk analysis or water quality monitoring program should follow viable CFU, which this technique reports, or monitor the total number of genomic copies (from clumped viable CFU, unfit or apoptotic cells, and free DNA) that might be reported by quantitative molecular biology techniques such as quantitative PCR.

Ocean beach waters contain a broad variety of organisms, including those that may develop mauve colonies on the CSA. Furthermore, because of the high concentration of organisms in the beach water, colony density on the plate can result in over-lapping colonies or growth in close proximity, making a firm color determination of a colony difficult. It is therefore necessary to confirm the identity of putative S. aureus colonies identified through colony color developed on CSA. Selectivity of this method for S. aureus relies on chromogenic media, followed by a confirmatory coagulase test. Development of mauve colonies on a CSA plate alone is not an accurate or reliable method for enumerating S. aureus colonies retrieved from recreational beach waters. The CHROMagar™SA manufacturer package insert notes some species of staphylococci other than aureus, as well as yeasts and corynebacteria, may develop mauve-colored colonies (Data on File, BD Diagnostic Systems21). Both false-positive (30%) and false-negative (8%) results were observed prior to the application of the confirmatory coagulase test. Based on results of 613 candidate colonies (including mauve and mauve-like on the filter/primary CSA plate), the most reliable method for counting S. aureus colonies is to select all mauve and mauve-like colonies, sub-culture on a gridded secondary CSA plate to assure color selection, and confirm with a 24-hour tube coagulase test. A coagulase test is preferable to the latex agglutination test, as the SLIDEX test yielded a number of uninterpretable results. The false-positive rate was reduced to zero by the inclusion of the coagulase confirmatory test. Inclusion of mauve-like colored isolates to the analysis increased the number of tested isolates by a factor of two, and reduced the apparent false-negative rate to zero. No 4-hour coagulase positive colonies converted to coagulase negative after 24-hr incubation; there was therefore no evidence of staphylokinase production, a potential interference in the tube coagulase test.22 The most frequent source of false-negative results was from colonies that exhibited a brown/mauve color. The most commonly recognized confounding species yielding false-positive results for the tube coagulase and latex agglutination tests are S. lugdunensis and S. schleiferi.23 False-positive results from the SLIDEX Staph-Kit Test are likely from S. schlieferi, S. lugdenensis, S. delphini, S. hyicus, and streptococci expressing receptors for immunoglobulins and fibrinogen (Strep. A, C, and G) and other non-aureus expression of clumping factors.24–27 A 4-hour tube coagulase test will slightly under-represent the CFU/mL in the water, but is more rapid.

The dynamic range of this assay can reasonably be tuned to higher incipient S. aureus concentrations by diluting the analyte waters. The CFU/mL range potentially measurable is determined by the number of non-mauve colonies growing in interference on the primary plate, and will vary from source to source. 10 and 20 mL of water were routinely filtered to yield detectible amounts of S. aureus from environmental waters.

Although it is unknown how many environmental S. aureus colonies did not produce mauve or mauve-like colors, false-negative, the sensitivity of the CSA + coagulase selection criteria if the algorithm presented here is comparable to or exceeds clinical sensitivity studies for detection of MRSA using the CHROMagar™ MRSA (Becton Dickinson and Company).28 Our experience does not support a 48-hour incubation on CSA.

The implications of establishing a reliable and practical approach to quantifying the presence of S. aureus in environmental waters are profound. Previous reports highlight the presence of MSSA and MRSA in public recreational water facilities.1–6,29 Clearly the epidemiological impact of knowing when these waters are potentially problematic is of major public health importance. The development of risk-models to predict what thresholds are appropriate for actions needed to reduce or prevent S. aureus contamination or infection can only be based on accurate point estimates of S. aureus and likelihood of acquisition following exposure. Furthermore, isolation of S. aureus followed by susceptibility testing and genetic typing may assist in the clinical management of subsequent infections acquired from these sources.

The positive predictive value of CHROMagar™SA as a single test is low. However, when used in conjunction with other accepted methods it can provide a simple, reliable algorithm to both identify and quantify S. aureus from environmental sources. The tube coagulase test yields the most reliable and cost-effective confirmatory results.

Table 3.

Predictive Power of Identification Algorithm

| Number of Mauve Colonies | ||||

| Result | Confirmed S. aureus | NOT S. aureus | Predictive Values | |

| CHROMagar™ SA alone | ||||

| positive | 58 | 25 | PPV | 0.70 |

| negative | 5 | 525 | NPV | 0.99 |

| CHROMagar™ SA + 24-hour tube coagulase | ||||

| positive | 58 | 0 | PPV | 1.00 |

| negative | 5 | 550 | NPV | 0.99 |

A positive result for the CHROMagar™ SA alone indicates a mauve colony on the secondary (gridded) plate. A positive result for CHROMagar™ SA + tube coagulase indicates the colony yielded positive results for both the CHROMagar™ SA chromogenic selection and 24-hour tube coagulase activity tests. PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Honolulu Medical Group Foundation, The Clean Water Branch of the Department of Health of the State of Hawai‘i, the OPAT outcomes Network, and the 2007 Summer Staph Institute.

References

- 1.Elmir SM, Wright ME, Abdelzaher A, et al. Quantitative evaluation of bacteria released by bathers in a marine water. Water Res. 2007 Jan;41(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshpe-Purer Y, Golderman S. Occurrence of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Israeli coastal water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 May;53(5):1138–1141. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.5.1138-1141.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler TL. Development of methods using chromagar media to determine the prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant S. Aureus (MRSA) in Hawaiian marine recreational waters [MS Thesis] Honolulu: Department of Microbiology, University of Hawaii; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charoenca N, Fujioka R. Associations of staphylococcal skin infections and swimming. Wat Sci Tech. 1995;31(5–6):11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charoenca N, Fujioka R. Assessment of Staphylococcus Bacteria in Hawaii Marine Recreational Waters. Wat Sci Tech. 1993;27:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seifried SE, Eischen M, Fowler T, Fujioka R, Tice AD. Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Recreational Beach Waters and Human Clinical Samples have a Similar Broad Genetic Diversity. American Society for Molecular Biology 107th General Meeting. Vol Toronto, CA: American Society for Microbiology; 2007. p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favero MS. Microbiologic indicators of health risks associated with swimming. Am J Public Health. 1985 Sep;75(9):1051–1054. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.9.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007 Nov 17;298(15):1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorwitz RJ. A review of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008 Jan;27(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815819bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Standard Methods Online, author. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 9213 Recreational Waters: Staphylococcus aureus in water by Tube Culture. 9213D [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Protection Agency UK, author. Enumeration of Staphylococcus aureus by membrane filtration. National Standard Method W. 2004;10(3) [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Public Health Association, author. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 9213 Recreational Waters. 2007;9213 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tice AD, Fowler T, Fujioka R. Staphylococcus aureus in recreational seawaters of Hawai‘i; Poster presented at: 42nd Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Geological Survey, author. U.S. Geological Survey Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations (Collection of water samples (ver. 2.0)). Vol Book 9, Chap. A42006. [8/29/08]. http://pubs.water.usgs.gov/twri9A3/

- 15.Warwick S, Wilks M, Hennessy E, et al. Use of quantitative 16S ribosomal DNA detection for diagnosis of central vascular catheter-associated bacterial infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Apr;42(4):1402–1408. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1402-1408.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovannoni SJ, Stingl U. Molecular diversity and ecology of microbial plankton. Nature. 2005 Sep 15;437(7057):343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature04158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLong EF, Karl DM. Genomic perspectives in microbial oceanography. Nature. 2005 Sep 15;437(7057):336–342. doi: 10.1038/nature04157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azam F, Malfatti F. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007 Oct;5(10):782–791. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukushima H, Katsube K, Hata Y, Kishi R, Fujiwara S. Rapid Separation and Concentration of Food-Borne Pathogens in Food Samples Prior to Quantification by Viable-Cell Counting and Real-Time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007 Jan 1;73(1):92–100. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01772-06. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havelaar AH, During M. Model studies on a membrane filtration method for the enumeration of coagulase-positive staphylococci in swimming-pool water using rabbit plasma-bovine fibrinogen agar. Can J Microbiol. 1985 Apr;31(4):331–334. doi: 10.1139/m85-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckton Dickinson & Company, author. BBL CHROMagar Staph aureus: package insertSparks, MD2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray PR, Baron EJ. Manual of clinical microbiology. 9th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown DF, Edwards DI, Hawkey PM, et al. Guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis and susceptibility testing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005 Dec;56(6):1000–1018. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weist K, Cimbal AK, Lecke C, Kampf G, Ruden H, Vonberg RP. Evaluation of six agglutination tests for Staphylococcus aureus identification depending upon local prevalence of meticillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) J Med Microbiol. 2006 Mar;55(Pt 3):283–290. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkerson M, McAllister S, Miller JM, Heiter BJ, Bourbeau PP. Comparison of five agglutination tests for identification of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997 Jan;35(1):148–151. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.148-151.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corso A, Soloaga R, Faccone D, et al. Improvement of a latex agglutination test for the evaluation of oxacillin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004 Nov;50(3):223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Personne P, Bes M, Lina G, Vandenesch F, Brun Y, Etienne J. Comparative performances of six agglutination kits assessed by using typical and atypical strains of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997 May;35(5):1138–1140. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1138-1140.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kircher S, Dick N, Ritter V, Sturm K, Warns P. Detection of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Using a New Medium, BBL CHROMagar MRSA, Compared to Current Methods; 104th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology; Vol New Orleans: LA2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harakeh S, Yassine H, Hajjar S, El-Fadel M. Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and saprophyticus resistant to antimicrobials isolated from the Lebanese aquatic environment. Mar Pollut Bull. 2006 Feb 16; doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]