Abstract

The compatibility of recovery work with the Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) model has been debated; and little is known about how to best measure the work of recovery. Two ACT teams with high and low recovery orientation were identified by expert consensus and compared on a number of dimensions. Using an interpretive, qualitative approach to analyze interview and observation data, teams differed in the extent to which the environment, team structure, staff attitudes, and processes of working with consumers supported principles of recovery orientation. We present a model of recovery work and discuss implications for research and practice.

Keywords: Assertive Community Treatment, recovery, measurement, grounded theory

Introduction

Despite the centrality of the concept of recovery in mental health services, serious scientific pursuit of recovery has been greatly hindered by a lack of clear definition and measurement strategies (Bond, Salyers, Rollins, Rapp, & Zipple, 2004; Liberman & Kopelowicz, 2005; Resnick, Fontana, Lehman, & Rosenheck, 2005). The concept of recovery evokes several common themes among consumers1, including hope, personal responsibility, social connection, citizenship, meaningful life activities, a positive identity, full life beyond the illness, and personal growth (Davidson, 2003; Deegan, 1996; Frese & Davis, 1997; Mead & Copeland, 2000; Ridgway, 2000; Roe & Chopra, 2003; Ware, Hopper, Tugenberg, Dickey, & Fisher, 2007). This emphasis on recovery is consistent with models of positive health, which posit that mental health is associated with leading a life of purpose and having quality connections with others (Ryff & Singer, 1998). Thus, recovery can be defined both in terms of objective indicators of community integration, such as role and community functioning, and subjective indicators of psychological well being, such as hope, self-esteem, and sense of purpose (Noordsy, et al., 2002). Empirical studies also suggest that objective and subjective domains of recovery are related. For instance, community integration has been associated with greater self-confidence, hopefulness, self-determination, and other facets of the recovery experience (Bond, Salyers, Rollins, Rapp, & Zipple, 2004; Carlson, Eichler, Huff, & Rapp, 2003; Resnick, Fontana, Lehman, & Rosenheck, 2005).

In addition to recovery as a consumer process and outcome, mental health services that support and enhance recovery are important to delineate. National policy makers (President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003) and mental health advocates (Anthony, 2000, 2004; Deegan, 1988; Mead & Copeland, 2000; Ridgway, 2000) place a value on recovery-oriented services that include active collaborative partnerships with consumers to help achieve personal goals, consistent messages of hopefulness and optimism (Dincin, 1975), consumer choice in all aspects of treatment (Drake, Rosenberg, Teague, Bartels, & Torrey, 2003), and a focus on consumer strengths (Rapp & Wintersteen, 1989). Recovery orientation also can be partially defined by describing what it is not. For example, a focus on medication adherence and avoiding hospitalization would fall short of recovery ideals. One purpose of our study was to clarify what recovery orientation means in daily practice.

Some authors have attempted to provide concrete guidance for how to establish recovery-oriented services (e.g., Anthony, 2000; Hopper, 2007), and recent efforts have been undertaken to assess the recovery orientation of programs, primarily through surveys. These survey-based assessments are still in the early stages of psychometric testing and validation (O'Connell, Tondora, Evans, Croog, & Davidson, 2005; Onken, Dumont, Ridgway, Dornan, & Ralph, 2004; Ridgway & Press, 2004). Moreover, survey responses may be particularly prone to social desirability bias given the nature of the topic content (e.g., belief in recovery, consumer choice, and coercion). More rigorous methods of assessment are needed.

We undertook a multi-method approach to studying recovery orientation in practice on Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams. The ACT model has been critiqued for not encouraging consumer empowerment and for potentially being coercive (Anthony, Rogers, & Farkas, 2003; Gomory, 2001; Williamson, 2002). Despite a wealth of evidence for the model’s effectiveness in reducing hospitalizations (e.g., Bond, Drake, Mueser, & Latimer, 2001; Ziguras & Stuart, 2000), little is known about the recovery orientation of ACT teams. On one hand, the ACT model targets consumers who have had difficulty engaging in other services and uses assertive outreach strategies such as close medication monitoring, behavioral contracting, outpatient commitments, and representative payeeships, all of which could lead to coercion (Dennis & Monahan, 1996; Gomory, 2001; Williamson, 2002). On the other hand, staff and consumer reports suggest that staff rarely use coercive methods (McGrew, Wilson, & Bond, 2002; Neale & Rosenheck, 2000) and most consumers report being satisfied with the services they receive (McGrew et al., 2002; Rapp & Goscha, 2004).

Our long-term goal is to develop a measure of the recovery orientation of ACT programs -- something akin to a fidelity scale. As with the development of any fidelity scale (Bond, Evans, Salyers, Williams, & Kim, 2000), our first step was to identify critical ingredients of recovery orientation. Because of the lack of clear, consensus-based definitions of recovery orientation, we used qualitative methods, which can be particularly informative when precise understanding of complex constructs is lacking (Buston, Parry-Jones, Livingston, Bogan, & Wood, 1998). Based on key informant ratings, we identified programs with high and low levels of recovery orientation and applied multiple methods to determine how the programs differed. We used ethnographically-informed methods of assessing the work of recovery, including on-site observations, interviews, and feedback sessions to discuss findings with participants.

Methods

Setting and Participants

Teams had to meet state standards for ACT certification and have a minimum level of ACT fidelity to be included: Dartmouth Assertive Community Treatment Scale (DACTS; Teague, Bond, & Drake, 1998) fidelity scores of 4.0 or above. In addition, we used recovery orientation ratings by informants to select two teams (see Measures below). As part of state-funded technical assistance for ACT, all teams had a consultant/trainer who conducted annual fidelity assessments, and provided hands-on training and consultation related to the ACT model (Salyers, et al., 2007). They also served as the informants for team selection. Participants included staff and consumers on the two ACT teams. Team A had a total of 9 staff and served a total caseload of 43 consumers; Team B had 12 staff and served 74 consumers. Excluding psychiatrists and prorating for part-time staff, caseload ratios were 5.6:1 for Team A and 7.4:1 for Team B, similar to other teams in the state. Team ratios in this state are often much lower than 10:1 due to the basic staffing requirements to form a team (e.g., specialist positions), regardless of consumer caseload.

Procedures

Teams were visited for six days over a 2–3 month period between July and December 2007. During our site visits, two doctoral level researchers with extensive experience with ACT and an advanced graduate student conducted chart reviews, interviews, observations, and distributed surveys. During most visits we also observed morning meetings and shadowed staff on visits to consumers when feasible. This paper focuses on our findings from interviews and observations. Each staff and consumer who was interviewed received a $50 gift card. Each participating team also received $1500 to offset costs associated with the time taken for site visits and other research-related activities. After we completed the majority of analyses, we returned to each of the programs to present and discuss preliminary findings. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis.

Measures

Recovery orientation ratings

In order to identify teams that would represent the ends of the recovery continuum for deeper study, consultant/trainers rated all certified ACT teams in Indiana on the degree to which staff instill hope, foster personal responsibility for illness management, and help consumers pursue meaningful life activities in their work with consumers (each on a scale from 1 to 5). These items were selected based on emerging themes that characterize recovery, including hope, personal responsibility, and meaningful lives (Noordsy, Torrey, Mueser, Mead, O'Keefe, & Fox, 2002). We did not use existing survey measures (e.g., O'Connell, Tondora, Evans, Croog, & Davidson, 2005; Onken, Dumont, Ridgway, Dornan, & Ralph, 2004; Ridgway & Press, 2004) because those are long measures and would require primary data collection from consumers/and or staff of all the teams in the state. We wanted a quick, but meaningful, way to identify programs worthy of more study (i.e., extreme teams) as the qualitative component was the main focus of the study.

Four trainers/consultants provided ratings of the programs they were familiar with, and a mean score was derived for each team. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation for the mean of the three items for teams with more than one rater (n = 12). The reliability was adequate (ICC = .70 overall). We considered .70 adequate minimum reliability because of the exploratory nature of the ratings (Downing, 2004). In addition, we did a second round of ratings three months later. The correlation between ratings was r = .70, p < .001. At the second round of ratings, there were 15 teams with more than one rater, and agreement between raters was good (ICC = .86 overall).

Our intent was to recruit the two teams rated by consultant/trainers as highest in recovery orientation and the two teams rated lowest. Out of the 32 certified ACT teams at the time of the study, the two highest rated teams accepted participation and were included. Among the four lowest rated teams, one was recruited, one declined participation, and two did not meet the minimum DACTS fidelity threshold. The fifth lowest rated team was selected and accepted. We collected data at all 4 sites. However, given that the fifth-lowest-rated team was not substantially different than several teams rated closely above it, and to remain closer to our initial goal of selecting extreme programs that clearly differentiated recovery, we compared just the highest and lowest rated teams. Mean informant scores across the two rating periods were 4.75 for Team A and 2.35 for Team B (with 5 as the highest possible).

Interviews

We targeted six staff and six consumers from each program to obtain a range of responses while maintaining a manageable sample size for qualitative analysis. For the staff interview sample, we targeted the roles of psychiatrist, team leader, nurse, case manager, substance abuse specialist, and vocational specialist, which are the primary roles on Indiana ACT teams. For the consumer interview sample, we targeted three of the most successful consumers on the team and three of the least successful, as identified through consensus of staff nominations2.

Semi-structured interviews focused on domains of activity typically targeted by treatment plans (i.e., housing, finances, medication, personal goals, employment, relationships, and substance abuse). We asked open-ended questions designed to explore how the ACT team assists consumers in each area and how the team responds when consumers face difficulties. For example, we asked consumers, “How is the ACT team involved with your housing?” and “Think of a time when you had extra difficulty with your housing; what did the ACT team do?” For staff, we asked, “How is the ACT team involved with clients’ housing?” and “Think of a recent client with housing difficulties; what did you do?” Opening questions for each domain were followed by probes to generate additional information. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and reviewed for accuracy. Interviews ranged from 30–90 minutes but averaged 60 minutes for completion.

Environmental observations

Rapp and colleagues (Goscha & Huff, 2002; Rapp & Goscha, 2006) have created checklists for hope-inducing and spirit-breaking behaviors that may be observed in mental health programs. Hope-inducing behaviors include treating people with respect, focusing on the positive, celebrating accomplishments, being there for the person, working towards goals that are important to the consumer, and promoting choice, education, and a future beyond the mental health center. Spirit-breaking indices include the presence of restrictive practices, negative staff perceptions of consumers, invasive interventions, disrespectful interactions, and discrimination. We created a checklist of these 96 behaviors for assessors to rate in terms of frequency of observance (none, some, a lot). Although we planned to complete the checklist after each visit, because of the length we found the checklist too cumbersome and inefficient to complete. Instead, we used it as a placeholder to cue written observations and notes throughout the visits. Observers also dictated notes directly into a tape recorder after each site visit. These were transcribed and reviewed to augment interviews.

Data Analysis

Interpretive analysis sought to identify “members’ meanings” and variations on local practice through close scrutiny of fieldnotes and transcripts (Charmaz, 2006; Emerson, Fretz, & Shaw, 1995; Miles & Huberman, 1994), informed by an overriding concern for recovery-orientation but open to unanticipated dimensions of teamwork or factors bearing upon it. We conducted ongoing analyses of transcripts and made adjustments to interviews based on early results; however, the lead questions about treatment domains remained the same. We kept working memos throughout, identifying provisional themes, questions for further pursuit, contradictions or tensions, and ambiguities in the data. Initially, three researchers read and open-coded the transcripts independently, informed by an overarching concern for indicators of recovery orientation. We then met and reviewed provisional lists and tagged segments from the first few transcripts. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. This process was repeated several times with new sets of transcripts, modifying the working codebook until a final set of focused codes was defined, “saturation” (a set of codes that could accommodate the content of all incoming data) having been reached. The labeling and organization of codes was aided by computer qualitative software (ATLAS.ti 5.5.9).

During focused coding, we divided each team’s interviews among three researchers and met weekly to review coding and working memos. Through this process, we created a second-order coding memo for each team, where we wrote observations based on our group discussions and highlighted important quotes from the interviews. Later we added a fourth member (clinical psychologist) to our analytic team for a fresh review of material. We independently read each coding memo and site visit notes and wrote a summary describing each ACT team. We then met to merge our descriptions into an overall “Recovery Orientation Profile” for each team, which described how it viewed the work of recovery, barriers to recovery orientation, how staff may have changed their views over time, tensions within the team, and distinctive team cultures (e.g., how they work together, consistency across the team). The profiles were then analyzed for critical components of recovery orientation.

Results

Two of the 12 consumers initially selected could not be interviewed (one was incarcerated and one was not currently receiving services). These were replaced by the next two consumers on the list. Although we initially targeted 12 staff for interviews, one team had a peer support specialist position that was added to the interview protocol. The other team had a psychiatrist who agreed, but could not be scheduled during our visits; we replaced this interview with another staff on the team. Overall we conducted 13 staff interviews across the two teams. At Team A we interviewed the team leader, psychiatrist, nurse, a case manager, substance abuse specialist, therapist, and peer support specialist. At Team B, we interviewed the team leader, nurse, two case managers, substance abuse specialist, and employment specialist. Based on the interviews, recovery orientation profiles, and observation notes, we identified four critical components of recovery orientation (see Table 1). Below we describe the environment, team structure, staff attitudes (including views of consumers, expectations, and language used), and processes of how ACT teams worked with consumers.

Table 1.

Examples of Recovery Critical Ingredients

| Critical Ingredient of Recovery Orientation |

Example on high recovery team | Example on low recovery team |

|---|---|---|

| Environment | ||

| Visual cues endorse recovery principles | Open waiting area, posters about recovery, posted team mission included recovery. | Separate waiting area and bathrooms, several signs with rules posted. |

| Team Structure | ||

| Peer specialist on team | Consumer provider as an integral part of the team, building on his experiences with recovery. | No consumer on the team. |

| Illness self-management training integrated onto team | Illness Management and Recovery program is used; active discussion in the morning meetings about using Illness Management and Recovery. | No illness self-management training program. |

| Staff Attitudes | ||

| Positive view of Consumers | Consumers are regular people: Consumers are treated as adults and are often viewed as like the staff in some way. | Consumers are different. Consumers often need to be protected or kept from disturbing others. |

| Positive expectations of consumers | Positive expectations for consumers: Consumers can work, achieve goals, and even graduate from ACT services. | Consumers can work in a gradual approach; Graduation is rarely discussed. |

| Strengths-based Language | Positive, strengths-based language. | Frequent labels, negativity. |

| Process of Working with Consumers | ||

| Consumers and staff collaborate on decisions | Primarily the consumer, sometimes with assistance; Consumer goals drive treatment. | Staff usually make decisions. |

| Team intervenes with demonstrated need | Consumers assumed to manage responsibility unless proven otherwise; When consumer is at risk of harming self or others; After other attempts have been made. | Team takes control early, and gradually gives control back as consumer prove themselves. |

| Team intervenes with consumer collaboration whenever possible, use control mechanisms as last resort | Process of discussions with consumer and team; Bring in supervisors when needed; Several examples of discussions that ended with consumer keeping more control. | Discussions within team primarily; use external controls frequently. |

Environment

Teams differed in the extent to which their physical environments contained visual cues endorsing recovery principles. Team A had an open waiting room that led directly to an interior hallway with offices. A receptionist sat at a desk in the same room as those waiting for services. One bathroom served both staff and consumers. In the office area, there were several posters with recovery themes, including a team mission statement: “[Team A] works in unity to empower individuals to strive towards recovery.” Team B’s waiting area was separated from the receptionist by a sliding glass window and from the rest of the offices by a locked door. The door had a window for medication delivery, with a sign on the back of the door reminding staff to close the window so that consumers “cannot reach behind the door and unlock it.” The waiting area had signs posted, including “No food or drink allowed in the waiting room except for water that is brought by case managers to take medications.” (There was, however, a pop machine located in the waiting room). There were separate bathrooms, and the bathroom labeled “staff” had decorations. We also saw active modifications of the environment for Team B. During one visit, a staff member propped a door open all the way, so that consumers who picked up their medications would not “sneak behind the door and hide there”.

The teams differed in the broader community environment as well. Team A was located in a more urban area than Team B. At Team B, the effects of the rural setting on their work came up frequently in interviews. When describing the way the team triaged medical concerns, one staff member stated it was because they “try to not bombard the doctors in town because we only have two places they [consumers] can go.” She went on to say that “We’ve pretty much burned our bridges with both of them at times… we do have some patients that the doctors in town refuse to see without a case manager because of behavior issues or med seeking issues and they won’t see them without one of us.”

Team Structure

The second critical distinction was how the teams were structured. Team A was developed with an explicit purpose of providing recovery oriented ACT services. Staff described interviewing potential employees for philosophy consistent with recovery. Team A employed a peer specialist, i.e., a self-identified consumer who was viewed as an integral part of the team. Team B was developed prior to explicit state and national initiatives encouraging “recovery”. This team did not employ a peer specialist. Both teams incorporated other evidence-based mental health practices of supported employment and integrated dual disorders treatment into their ACT teams. However, Team A also provided Illness Management and Recovery whereas Team B did not. We observed two sessions with the peer specialist using this curriculum with consumers, and the program was frequently mentioned in morning meetings.

Staff Attitudes

View of consumers

Interviews and observations frequently revealed a “like me” empathetic response from staff at Team A, where staff explicitly put themselves in the shoes of the consumer or used their own experiences with consumers. For example, a consumer had expressed that he did not want the nurse to accompany him to physician visits. The staff told the observer, “I wouldn’t want to have someone around for that…If I was them, I think I would be upset about [losing my independence] too.” The peer specialist on this team also used his own experiences to relate directly to consumers.

On Team B, references to being like consumers were rare. In one interview, the staff member described a conversation with a consumer. She referenced herself, but with the implication that her experience was different from the consumer’s: “And I said ‘When I decided to go to college, it wasn’t someone else’s job for me to figure it out. In the real world you have to do a little investigation yourself’”.

On Team B, consumers were sometimes referred to in child-like terms. A staff member said: “One thing we try to really, really teach our clients and something as a mom, a rule I went by as a mom, if you tell me the truth you will never ever be punished, never, no matter what it is. So I always share that with a client…. We won’t yell at you for not taking [medications]. The big bad wolf does not come and eat you up or anything”. Another staff member said, “…they [clients] come here and then they just blossom because we’re constantly on them, we’re their parents about everything.” In contrast, Team A described trying to avoid parenting. One staff said, “Sometimes when we have their money and we know that they are making bad choices, we struggle with not being parental. That is hard.”

Expectations of consumers

Team A staff demonstrated positive expectations of consumer ability by actively working towards and encouraging graduation from ACT, as well as frequently talking about consumers’ ability to achieve goals. Related to an expectation for employment capacity, one staff talked about “breaking that myth of, ‘I have schizophrenia and I can’t work,’ because a lot of clients are like that. That is what they have heard all their lives. Having schizophrenia or any other diagnosis doesn’t prevent you from working.” Team B staff also endorsed the ability to work, but in a more protected, gradual way. Emphasizing lack of experience, fear, low self-esteem, and symptoms of consumers, a staff member said: “It’s just very difficult for a lot of them to maintain anything in the community, so we are able to provide them a safe haven essentially. And hopefully a time limited safe haven that they can move on and learn some skills and find a job in the community.”

In terms of actual graduation from ACT services, Team A staff were planning graduation with two different consumers. One consumer, however, was not sure that he was ready: “They mentioned graduating and passing and I just thought well, they’re just doing that to make me feel better like I accomplished something, but I didn’t realize it meant that they didn’t think I needed any ACT help anymore.” Team B staff did not mention graduating consumers at all. One consumer talked about graduation as an impossibility: “Well, when I talked to Dr. [deleted] about it he said, ‘Well I’m sure that you think there’s a point where you’ll graduate from the ACT Team.’ But he’s very honest. He said it’s either state funded or federally funded unless you transfer, you know, it’s the money that’s involved…If you transfer to another state or another city then they’ll let you go, but they’ll hook you up with the mental health there. So there’s really no getting away from it.” Although we do not know what the consumer was actually told, she perceived that graduation from ACT is not possible.

Language

For staff at Team A, the word recovery was mentioned frequently in interviews. For example a staff member described that, “our belief system around recovery includes physical health as well as mental health and it’s important that all their health concerns are addressed ‘cause that’s part of the recovery process.” Among staff on Team B, recovery language was notably absent, even though they endorsed ideas related to supporting independence. At times though, true endorsement of independence and recovery constructs appeared questionable, e.g., “We try to promote their personal goals, even though they might seem ridiculous to us.”

The language at Team A reflected positive appraisals and staff reframed difficult issues and potentially bad choices into something positive. For example, for one consumer who had trouble with the law the prior week, a team member said, “She almost violated her probation. She almost was in a fight with her neighbors. But only almost.” In contrast, the language at Team B appeared more judging, with the use of terms such as “lying” and “manipulative,” and labels, such as “borderlines” and “schizophrenics”. This language was not heard at Team A.

Process of Working with Consumers

Finally, a critical difference between the teams was the process of how they worked with consumers. First, teams differed in who made decisions about treatment (consumers vs. staff). We observed many interactions in which consumers from Team A had choices and staff honored them. For example, one consumer told a staff member that he did not want to be accompanied to medical appointments anymore. The staff responded by expressing concern, but said, “Whatever your decision is, I will respect that. I will honor that.” In another example, a consumer described how the team helped with her physical health issues when she first joined the team, which allowed her to pursue her interests (e.g., walking). In contrast, the staff on Team B appeared to be the primary decision-makers regarding treatment. We observed that staff discussed issues, decided what the best decision was, and then told the consumer what was going to or what had already happened. In one instance a staff person seemed surprised that a consumer accomplished something independently: “Well, what do you know, he actually did it himself”. In consumer interviews, 4 of the 6 used the words “held hostage”, “push” or “intrusive” to describe Team B (including a consumer deemed “successful” by the team).

Next, there were differences in when the team stepped up efforts to intervene in a difficult situation (e.g., when the consumer was at risk for harm or after other less intensive attempts had failed). While consumer goals seemed to drive treatment choice on Team A, staff members also drew boundaries, particularly regarding safety and legal/ethical issues. For example, the team chose to not advocate for a consumer who was going to be evicted because her son was trafficking drugs out of her apartment.

Team B tended to step in much earlier, and medication management was one treatment domain in which teams’ intervention thresholds clearly differed. Consumers on Team A usually managed their own medications and the team only intervened when help was needed. A Team A staff member said, “We have taken a stand from the beginning with this team that we are going to try and limit the amount of people we see every day for medication monitoring specifically because when you give people independence and empowerment, they often do a lot better than we think they do.” At the time of our initial visit, only one person on Team A was on daily medication delivery, and we heard several examples of the team deciding not to increase medication monitoring. For example, in a discussion about a consumer who was not currently taking medications, one staff member said, “He does better when it’s his own choice. He’s made good choices in the past and bad choices in the past. If we give him independence, I think he’ll make good choices.”

In contrast, Team B started most people on daily medication monitoring. At the time of our initial visit, 29 (39%) of the consumers were on daily medication delivery. Staff said: “We usually put them on daily meds for the first 30 days and then work to every other day and then go for the weekly, and then we’ll do spot checks … to make sure they are not taking too many or not enough.” When talking to consumers about medication assistance, one expressed concern about this level of dependence on the team: “If they start doing everything for me, I am not going to know how to do it when it is my time to do it. I have been taking care of myself forever. I am 38 years old. Some things I need to be doing on my own. Because it takes away from me, it takes away my pride and freedom, and I don’t like that. It hurts me.” When consumers on Team B have difficulty taking medications, the first response is to increase monitoring. One staff described the process, “If they are not taking them [medications] then we increase their times of monitoring throughout the day. I mean almost to the point of hand-feeding them.” In the morning meeting at Team B, we did hear one example about a consumer who was forgetting medications, to which the doctor replied, “Until he proves himself unreliable, which he hasn’t, we’ll allow him to take care of himself”.

Lastly, the teams differed in how they intervened. Team A approached decisions about taking more control through discussions among team members and with consumers. The team also used treatment planning meetings or family meetings to address issues and stressed weighing the pros and cons when tough decisions had to be made. Team A also sought guidance from peers and supervisors. For example, the team contacted supervisors to help determine how to make contact with a consumer who had a violent history. Team B frequently used external controls, such as outpatient commitment, when intervening with consumers. In one instance when a consumer was not present for daily medications and they suspected the consumer might “bottom out,” the response was to obtain an outpatient commitment. Other external controls used by Team B included use of agency-run apartments, where consumers would have to follow rules or lose their housing, and use of local police, who were called in to the agency to transport consumers to forensic units. Sometimes the control mechanisms were more indirect, such as withholding information (e.g., not sharing with a consumer the parameters of her outpatient commitment).

Follow-up Feedback Sessions

Approximately 18 months after our initial visits, we returned to the teams to present preliminary findings and to discuss perceived applicability of our findings and whether things had changed. We presented two models of care that we initially identified - coaching versus parenting. The coaching model was based on viewing consumers as capable, having positive expectations of consumers, supporting consumer choice and only intervening when there is a high risk of danger and after discussion. The parenting model was based on an authoritarian style, viewing consumers as needing protection, having low expectations for consumer capacity, making most decisions for consumers, and intervening early to prevent problems.

At the time of the follow-up visit, Team A’s office arrangements were the same, but they no longer had the recovery poster in the meeting room. Several staff had left the team and the team had 2 vacancies. Team A responded positively to the coaching model and stated they were “trying to be” coaches. However, the team reported that they were leaning more towards the authoritarian model in order to increase client contact because the team was no longer meeting the minimum level for certification. They described how more frequent medication monitoring would be one “easy” way to increase client contact, but were struggling with that approach. The discussion focused on relationships with consumers, and they reported feeling pushed by a service context that required visits they believed were at odds with their view of the recovery model.

At the time of the follow-up visit, Team B had a “working together” poster in the meeting room; the waiting area and separate bathrooms remained the same. There was a new team leader, and 2 case managers had left, but a core of 6 staff had remained the same over 6 years. In response to the models, Team B staff reported that they “zigzagged” between the models, stating “sometimes we are definitely parenting,” depending on consumer need. Another staff member said they “flip back and forth depending on the risk involved,” highlighting that their role is to keep people out of the hospital. Staff also discussed the rural nature of their service area. They had only one doctor who served Medicaid clients, and “if we burn that bridge, the client will be out of luck”. Lack of transportation, employment opportunities, and natural consequences were also common. For example, staff talked about the police bringing clients to the center rather than jail when consumers break the law.

Discussion

Despite teams’ similarities in baseline fidelity to the ACT model, we experienced many differences between the teams during our visits – both teams were meeting similar ACT model standards, but were approaching the work very differently. Some of the key differences between them were reflective of agency or team culture and articulate a preliminary list of critical ingredients for recovery-oriented ACT in Table 1: visual cues in environment endorse recovery, peer specialist fully integrated on the team, illness self-management training integral to team interventions, view consumers as regular people, positive expectations for consumers, use of strengths-based language, consumer and team collaboration on treatment decisions, team intervenes with demonstrated need, and team intervenes with consumer collaboration whenever possible and uses control mechanisms as last resort.

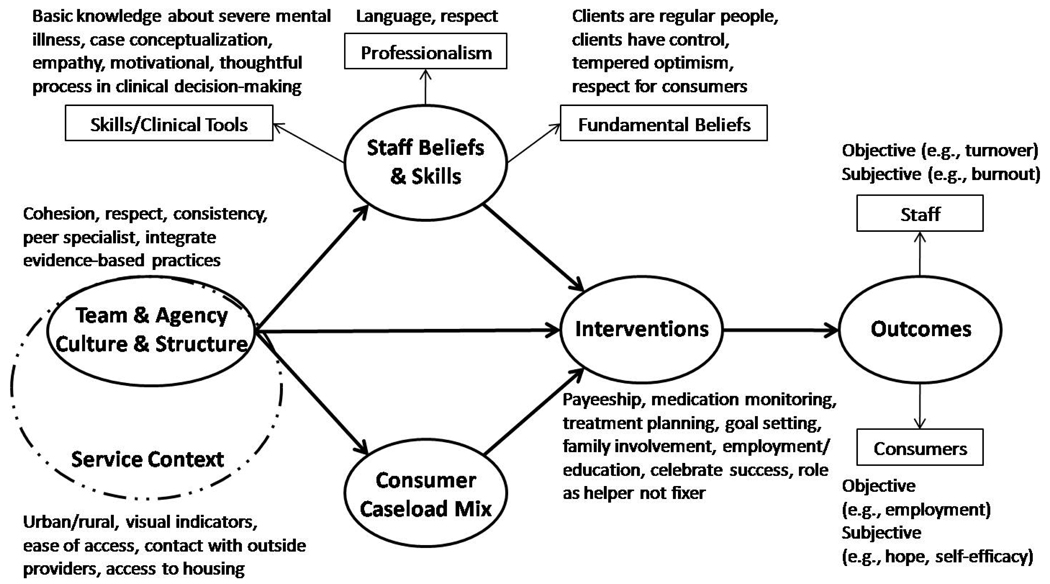

Based on team differences, we developed a visual model of the work of recovery on ACT teams (see Figure 1). Our model shows that teams consist of staff with a mix of skills, beliefs, and attitudes that can influence how work is done. Teams work with a particular caseload of consumers. For ACT teams in Indiana, admission standards are similar across the state, ensuring that ACT teams focus on consumers who are the most disabled by mental illness. However, teams may vary in the extent to which their caseload includes consumers who experience high symptom acuity, homelessness, substance use, or other complicating factors. The interventions that teams used (i.e., who made treatment decisions, when the team intervened, and how the team intervened) were guided by staff beliefs and client needs. The teams, however, are all set within the broader treatment context (e.g., programs held to state standards for funding, located in rural or urban areas), and this broader context is critical.

Figure 1.

Model of Recovery Work on ACT Teams

Concepts of risk and trust appeared central to treatment decisions and differentiated two distinct models of recovery work: coaching and parenting. Coaching teams have high trust in consumers’ ability to self-manage and view the risks as low. The team environment would suggest trust, with open areas and amenities shared between consumers and staff. The majority of consumers on coaching teams would manage their own medications and receive more intensive monitoring if repeatedly demonstrating need. This approach seems closely related to staff beliefs that consumers are “like us” in fundamental ways and should be afforded the greatest freedoms possible. As in Davidson’s view (2007), coaching teams function like the Home Depot motto: “You can do it. We can help.”

The coaching role for the team is consistent with tenets of self-determination theory which posits that human potential is at its best when internal motivation is facilitated (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Internal motivation is highest when people have a sense of control, perceive themselves as able to do the task, and feel supported to do so. Other clinical applications of self-determination theory have shown that supporting autonomy leads to greater internal motivation and perceived competence, which in turn has been related to clinical outcomes such as greater abstinence rates in smokers (Williams, et al., 2006), better glycemic control in patients with diabetes (Williams, McGregor, Zeldman, Freedman, & Deci, 2004), weight loss (Williams, Grow, Freedman, Ryan, & Deci, 1996), and more effective medication utilization (Williams, Rodin, Ryan, Grolnick, & Deci, 1998). By placing trust in the hands of the consumers, coaching teams may provide more autonomy support and foster the development of competence.

It may be easy to see these programs as though one team is “good” and the other ”bad,” particularly in light of recovery concepts. But both teams expressed feelings of genuine concern and care for the consumers and took pleasure in positive events in consumers’ lives. And, there were some downsides to the coaching approach. The team’s hands-off approach may foster independence quickly, but at least one consumer reported that the process was too fast -- the team believed the consumer was more ready than he did. Differences in staff and consumer expectations of need are common (Crane-Ross, Roth, & Lauber, 2000), even in teams that are actively trying to be more consumer-directed. Another difficulty was that the team struggled with maintaining fidelity to the ACT model over time. At the time of our follow-up visit, the team was in danger of being de-certified for infrequent consumer contacts. Although the less frequent contacts could reflect staff vacancies, it is also possible that the initial coaching drifted into a mild form of neglect with the team not intervening enough, perhaps in service of the recovery ideal. During the follow-up visit, staff reinforced the notion that they wait until a consumer wants something and do not “shove it down their throats,” which was clearly a step towards a more passive team approach, perhaps swinging the pendulum beyond the more active coaching approach that we observed during the data collection phase of the study. A passive approach could represent how the work of recovery could be taken to an extreme without checks for service context, consumer needs, and process and outcomes desired by payers, families, and many consumers themselves (e.g., outreach, prevention of hospitalization, homelessness, incarceration). It is clear that some balance between the standards of professional care (in this case, service intensity and taking an assertive approach to provision of care) and consumer choice is needed (Salyers & Tsemberis, 2007), but the balance appears difficult to maintain over time.

The service context was also a dominant feature in the parenting and risk management approach of Team B, particularly the rural nature of the setting. The stated concern by several staff was that one bad interaction with a consumer could “burn a bridge” for other consumers. In rural areas, resources such as doctors, landlords, and employers are scarce, and the team appeared to put a great deal of energy into protecting relationships with those resources. This protection evidenced itself in more frequent use of control mechanisms like daily medication monitoring, restricting access to money and housing, using outpatient commitments, and hospitalizing consumers. These findings are consistent with the work of Angell and colleagues (2006) who also found rural ACT staff to perceive greater risk and responsibility for protecting consumers and to act more paternalistically than the urban team she studied.

Although our proposed model of recovery work (Figure 1) shows direct links between interventions and outcomes, the impact of recovery orientation on consumers and staff remains to be seen. In our companion paper (Salyers, et al., under review), we found no differences between these teams in consumer reports of being active in treatment, degree of illness self management, hopefulness, optimism, perceived choice, or satisfaction. Given the striking differences in the culture of the teams, the lack of consumer differences on these measures calls for further investigation. It may be that our survey measures did not account for baseline consumer differences, were not sensitive, or reflected possible halo effects as found in other measures of quality of life (Atkinson, Zibin, & Chuang, 1997) or satisfaction with housing (Levstek & Bond, 1993). Conversely, it may be that the work of recovery on these teams truly is unrelated to consumer outcomes. Particularly for the team at risk for falling out of compliance with ACT, consumer outcomes may, in fact, suffer from taking recovery concepts too far and providing too few or infrequent services to consumers who refuse services but are clearly in need of intervention. Other work, though, has shown that relationship-centered care can have positive impacts in other areas of medicine. For example, relationships in which patients are activated to take greater control in their care appear to be particularly important predictors of physical health outcomes (Michie, Miles, & Weinman, 2003). Clearly, the work of recovery has to be balanced against context, including consumer needs.

We initially viewed recovery work as a stable concept that could be applied to an entire team (i.e., a team would be more coaching or parenting). We found, however, that the approaches were probably variably applied within teams, depending on the staff and the clients being served. It is possible that staff turnover of some key roles, particularly a team leader, doctor, or nurse, may have a large impact on how teams operate. Outside forces such as impending de-certification can also change how a team approaches the work of recovery. If an agency’s funding is in jeopardy, the team’s staff may be pressured to make increased visits or apply additional constraints to consumers despite perceived consumer need. The predominance of our observations related to recovery work may lean towards one approach more than another, but the approaches are less consistently observed than we first assumed.

In terms of measuring ACT recovery orientation in the future, the data collection methods of this study are far too involved to be useful in large scale recovery measurement (e.g., to measure recovery orientation across an entire state’s ACT teams). With a preliminary set of critical ingredients identified, it is possible for future work to include qualitative methods but in a more streamlined fashion. To this end, we recommend a combination of observer ratings, consumer and staff ratings, and shortened interviews to measure recovery orientation. The recovery orientation ratings of key informants we used to select teams are not likely to be useful alone. Our informants had years of prior experience with the teams, and without that, we doubt that global items would be very useful to discriminate among programs. Our richest data sources, with strong participation rates, were interviews with staff and consumers. However, using traditional qualitative methods for identifying themes and constructing a theory of how they relate required a great deal of staff time and energy (both from researchers and participants) – something that would not be feasible for ongoing program evaluation unless done more efficiently. In our interviews, a few treatment areas elicited a great deal of information, particularly questions about medications, money, and personal goals. One approach may be to limit interviews to these key areas. Also, if themes and critical ingredients we found are consistent in future samples, then a coding system could be created that would reduce much of the time involved. Further, many of the concepts we identified were similar to the hope-inducing and spirit-breaking dimensions described by Rapp and colleagues (Goscha & Huff, 2002; Rapp & Goscha, 2006); however, a checklist based on each of these dimensions proved unwieldy. Instead, future work could pare the Rapp list to those items most closely embodying the critical ingredients and corresponding examples in Table 1. This quantitative methodology could be compared with abbreviated qualitative methods we suggest above in the next iteration of this research.

Our study closely examined the work of recovery on two teams with high ACT model fidelity but differing levels of recovery orientation. One limitation is how teams were selected – on the basis of key informant ratings in one state. Also, we did not conduct a full ethnographic study with repeated interviews and long-term observations. Our follow-ups with teams hinted at some slight philosophical shifts over time, also making us aware that these parenting and coaching approaches are two themes derived over a discrete period of time and may exclude other approaches, including more passive approaches that may be inconsistent with ACT services and other service contexts. Our work did not explore the possibility of other approaches as they develop over time or on other teams. It would be important to replicate our study among other treatment teams to validate our findings and refine the articulation of critical ingredients of recovery orientation.

This study sheds light on the factors that contribute to the work of recovery and critical ingredients that characterize a strong recovery orientation on ACT teams. Recovery work on these intensive treatment teams is possible, but clearly involves hard work and balancing by staff and consumers. The effects of the balancing act over time are unclear, though, and longer follow-up will be needed to see if recovery oriented ACT is sustainable. This study also identified potentially helpful ways to measure recovery orientation and point to future assessment possibilities in evaluating and supporting recovery on ACT teams. The measurement challenge, however, will be accounting for the constraints and enablements of local context in order to capture what it means to do recovery-oriented work.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an IP-RISP grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R24 MH074670; Recovery Oriented Assertive Community Treatment). We appreciate the involvement of staff and consumers who participated, and the assistance of Angela Donovan, Candice Hudson, Dawn Shimp, and Jenny Lydick in the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

We choose the term “consumer” (of mental health services) rather than client, patient, service-user or a number of other possibilities because it is more active than some of the others, and is commonly used in our service context. We recognize, however, the acceptability of terms varies.

A concurrent study was examining success and failure on ACT teams and guided this interview sample selection (Stull, McGrew, & Salyers, in press).

Contributor Information

Michelle P. Salyers, VA HSR&D Center on Implementing Evidence-based Practice, Roudebush VAMC and Regenstrief Institute, Inc; Co-Director, ACT Center of Indiana; Associate Professor, Department of Psychology, Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI).

Laura G. Stull, Department of Psychology, IUPUI.

Angela L. Rollins, ACT Center of Indiana; Assistant Research Professor, Department of Psychology, IUPUI.

Kim Hopper, Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, and Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

References

- Angell B, Mahoney CA, Martinez NI. Promoting treatment adherence in assertive community treatment. Social Services Review. 2006;80:485–526. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. A recovery-oriented service system: Setting some system level standards. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2000;24(2):159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA. The principle of personhood: The field's transcendent principle. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004;27(3):205. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.205.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony WA, Rogers ES, Farkas M. Research on evidence-based practices: Future directions in an era of recovery. Community Mental Health Journal. 2003;39(2):101–114. doi: 10.1023/a:1022601619482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson M, Zibin S, Chuang H. Characterizing quality of life among patients with chronic mental illness: A critical examination of the self-report methodology. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:99–105. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, Latimer E. Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: Critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management & Health Outcomes. 2001;9:141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Evans L, Salyers MP, Williams J, Kim HW. Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2(2):75–87. doi: 10.1023/a:1010153020697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Salyers MP, Rollins AL, Rapp CA, Zipple AM. How evidence-based practices contribute to community integration. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40(6):569–588. doi: 10.1007/s10597-004-6130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buston K, Parry-Jones W, Livingston M, Bogan A, Wood S. Qualitative research. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:197–199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.3.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson L, Eichler MS, Huff S, Rapp CA. A tale of two cities: Best practices in supported education. Lawrence, KS: The University of Kansas School of Social Welfare; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crane-Ross D, Roth D, Lauber BG. Consumers' and case managers' perceptions of mental health and community support service needs. Community Mental Health Journal. 2000;36(2):161–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1001842327056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L. Qualitative studies in psychology. New York, NY, US: New York University Press; 2003. Living outside mental illness: Qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia; p. 227. (2003) xii. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The "what" and "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11(4):227–268. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE. Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 1996;19(3):91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan PE. Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1988;11(4):12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis DL, Monahan J. Coercion and aggressive community treatment: A new frontier in mental health law. Plenum Series in Social/Clinical Psychology; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Dincin J. Psychiatric rehabilitation. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1975;13:131–147. doi: 10.1093/schbul/1.13.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing SM. Reliability: On the reproducibility of assessment data. Medical Education. 2004;38(9):1006–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Rosenberg SD, Teague GB, Bartels SJ, Torrey WC. Fundamental principles of evidence-based medicine applied to mental health care. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2003;26(4):811–820. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(03)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson RM, Fretz RI, Shaw LL. Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frese FJ, Davis WW. The consumer-survivor movement, recovery, and consumer professionals. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1997;28:243–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gomory T. A critique of the effectiveness of assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goscha R, Huff S. Basic Case Management Manual. Lawrence, Kansas: The University of Kansas School of Social Welfare; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper K. Rethinking social recovery in schizophrenia: What a capabilities approach might offer. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(5):868–879. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levstek DA, Bond GR. Housing cost, quality, and satisfaction among formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness in two cities. Innovations and Research. 1993;2(3):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A. Recovery from schizophrenia: A concept in search of research. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(6):735–742. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew JH, Wilson R, Bond GR. An exploratory study of what clients like least about assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:761–763. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead S, Copeland M. What recovery means to us: Consumers' perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal. 2000;36:315–328. doi: 10.1023/a:1001917516869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J. Patient-centredness in chronic illness: what is it and does it matter?[see comment] Patient Education & Counseling. 2003;51(3):197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MS, Rosenheck RA. Therapeutic limit setting in an assertive community treatment program. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:499–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser K, Mead S, O'Keefe C, Fox L. Recovery from severe mental illness: An intrapersonal and functional outcome definition. International Review of Psychiatry. 2002;14(4):318–326. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connell MJ, Tondora J, Evans A, Croog G, Davidson L. From rhetoric to routine: Assessing recovery-oriented practices in a state mental health and addiction system. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2005;28:378–386. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.378.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onken SJ, Dumont JM, Ridgway P, Dornan DH, Ralph RO. Update on the Recovery Oriented System Indicators (ROSI) measure: Consumer survey and administrative-data profile. 2004 Joint Conference on Mental Health Block Grant and Mental Health Statistics; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Final Report. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003. Achieving the promise: Transforming mental health care in America. DHHS Pub. No. SMA-03-3832. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp CA, Goscha RJ. The principles of effective case management of mental health services. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2004;27:319–333. doi: 10.2975/27.2004.319.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp CA, Goscha RJ. The strengths model: Case management with people with psychiatric disabilities. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp CA, Wintersteen R. The strengths model of case management: Results from twelve demonstrations. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1989;13:23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick SG, Fontana A, Lehman AF, Rosenheck RA. An empirical conceptualization of the recovery orientation. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;75(1):119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway P, Press AN. An Instrument to Assess the Recovery and Resiliency Orientation of Community Mental Health Programs: The Recovery Enhancing Environment Measure (REE). Paper presented at the Joint National Conference on Mental Health Block Grant and National Conference on Mental Health Statistics; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgway PA, editor. The recovery papers: Volume 1. Lawrence, Kansas: The University of Kansas School of Social Welfare; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roe D, Chopra M. Beyond coping with mental illness: Toward personal growth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2003;73(3):334–344. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, McKasson RM, Bond GR, McGrew JH, Rollins AL, Boyle C. The Role of Technical Assistance Centers in Implementing Evidence-Based Practices: Lessons Learned. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2007;10(2):85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, Stull LG, Rollins AL, McGrew JH, Hicks LJ, Thomas D, et al. Measuring the Recovery Orientation of ACT. doi: 10.1177/1078390313489570. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers MP, Tsemberis S. ACT and recovery: Integrating evidence-based practice and recovery orientation on assertive community treatment teams. Community Mental Health Journal. 2007;43(6):619–641. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stull LG, McGrew JH, Salyers MP. Staff and consumer perspectives on defining treatment success and failure in assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.9.929. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE. Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: Development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(2):216–232. doi: 10.1037/h0080331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Hopper K, Tugenberg T, Dickey B, Fisher D. Connectedness and Citizenship: Redefining Social Integration. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(4):469–474. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70(1):115–126. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, McGregor HA, Sharp D, Levesque C, Kouides RW, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Testing a self-determination theory intervention for motivating tobacco cessation: supporting autonomy and competence in a clinical trial. Health Psychology. 2006;25(1):91–101. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, McGregor HA, Zeldman A, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Testing a self-determination theory process model for promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management. Health Psychology. 2004;23(1):58–66. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, Rodin GC, Ryan RM, Grolnick WS, Deci EL. Autonomous regulation and long-term medication adherence in adult outpatients. Health Psychology. 1998;17(3):269–276. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson T. Ethics of assertive outreach (assertive community treatment teams) Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2002;15:543–547. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200209000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziguras S, Stuart G. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:1410–1421. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.11.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]