Introduction

Tobacco use is the single greatest preventable cause of morbidity and premature mortality in the United States today and is responsible for more than 440,000 deaths—about one in five—each year.1 Because of the chronic and relapsing nature of tobacco dependence, addressing this problem at a health system level remains difficult. Tobacco use is so entrenched in the lifestyles of many Americans—including approximately 390,000 Northern California Kaiser Permanente (KP) members—that nothing short of a multifaceted program can even begin to address the problem. To combat the enormous burden on the health of our members caused by tobacco dependence, the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Region (KPNC) undertook a systems approach that relies on the incremental impact of multiple interventions. The KPNC Tobacco Dependence Program has contributed to a more than 10% reduction in smoking prevalence as well as to a 30% increase in HEDIS scores on the “Advising smokers to quit” measure for the period spanning from reporting year 1998 through reporting year 2003, substantially increased both attendance at tobacco-cessation programs and use of antismoking medication, and has become a model for health care systems nationwide.

Initiated in 1998 and fully implemented by 2004, the Tobacco Dependence Program (Figure 1) hypothesized that a multifaceted, evidence-based program can reduce tobacco use among members of KPNC by using four main strategies:

For patients: routine assessment of tobacco use, counseling, and referral. For clinicians: training, audit, and feedback linked to incentives

Enhanced health plan benefits

Menu of tobacco cessation programs for members

Worksite and community tobacco control efforts.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrates KPNC Tobacco Dependence Program's three-tiered approach to reducing tobacco use (ie, smoking) among patients visiting KPNC medical centers.

Key relationships studied in this program can be identified by answering three questions:

How effectively does the combination of clinician training, audit, and feedback improve rates at which clinicians advise patients to quit smoking?

Will enhanced benefits for smoking-cessation medications and programs increase the number of smoking-cessation medication prescriptions and the number of members attending tobacco-cessation programs?

How effectively is the prevalence of tobacco use decreased by clinical training, audit, feedback, enhancement of health plan benefits, and policies for worksite control of tobacco use?

… nothing short of a multifaceted program can even begin to address the problem.

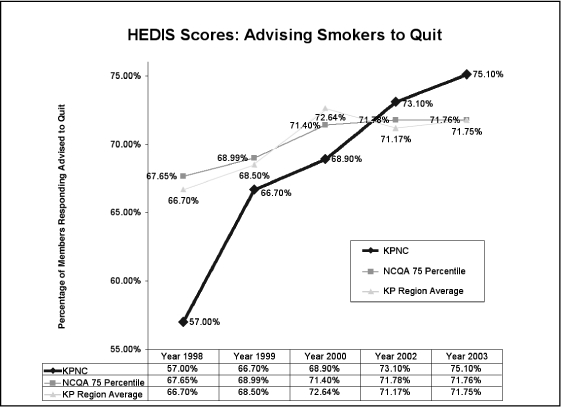

The Tobacco Dependence Program is aligned with KP's mission to provide affordable, high-quality health care services that improve both the health of our members and the health of the communities we serve. Our program uses all of the strategies supported by current literature as well as the best practices identified throughout the country to help us reach the Healthy People 2010 goal of reducing the prevalence of tobacco use to <12%.2 Although most smoking-cessation trials do not provide direct evidence of health benefits, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found credible evidence that smoking cessation lowers the risk for heart disease, stroke, and lung disease. The USPSTF concluded that credible indirect evidence shows that even small increases in the quit rates resulting from tobacco-cessation counseling would produce important health benefits and that the benefits of counseling interventions substantially outweigh any potential harms of these interventions.3 The USPSTF also found strong evidence that brief smoking-cessation interventions—including screening, brief behavioral counseling (three minutes or less), and pharmacotherapy delivered in primary care settings—effectively increase the proportion of smokers who successfully quit smoking and remain abstinent after one year.3 That at least 70% of smokers visit their health care practitioner each year4 shows clearly that clinicians are uniquely poised to intervene with patients who use tobacco.3 Use of cessation programs and medications can greatly increase success rates. The National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) has made “advising smokers to quit” a quality measure and uses Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) data for assessment. In 1998, KPNC's HEDIS scores on the “Advising Smokers to Quit” measure were substantially below the 75th percentile benchmark set by NCQA and thus showed that KPNC members were inconsistently advised by clinicians to quit smoking and that work was needed to improve the quality of care for members who smoke (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graph of responses to CAHPS survey shows that KPNC has dramatically improved its performance on the HEDIS quality measure for advising smokers to quit smoking. For the HEDIS quality measure since inception of its Tobacco Dependence Program, KPNC has moved from being one of the lowest-performing to becoming one of the highest-performing KP Regions.

“I am so impressed with the KPNC Tobacco Dependence Program. It should be an inspiration to health systems throughout the country. If the rest of the country operated the way KPNC does, we could save thousands of lives every year.”

—Steven A Schroeder, MD, Director, Smoking Cessation Leadership Center, University of California San Francisco

Objectives of the Tobacco Dependence Program

The KPNC Tobacco Dependence Program has several main objectives:

To increase the number of current smokers who are advised to quit at office visits to (or above) the 75th percentile benchmark defined by NCQA (an external measure) and to (or above) KPNC's long-term goal of 65% as reflected by responses to the KP Member and Patient Survey

To increase the number of smokers attending behavioral interventions for smoking cessation

To increase the number of smokers receiving prescriptions for smoking-cessation aids

To increase the number of KPNC campuses which are smokefree

To collaborate on tobacco-control programs in the external community and to support policies and legislation designed to control tobacco use

To reduce the prevalence of tobacco use among KPNC members and to exceed the Healthy People 2010 target of reducing the prevalence of tobacco use to below 12%.

Scope and Significance of the Program

Approximately 23% of American adults smoke.5,6 Although prevalence of smoking is lower among Californians because of successful statewide policies for tobacco control, physiologic dependence on tobacco still burdens nearly 400,000 of our KPNC members. Although most want to quit smoking, few succeed without help.5,6 Treatment for tobacco use is well known to double rates of successfully quitting.3 The positive effects of treatment and prevention of tobacco dependence extends well beyond the population of current smokers to those exposed to secondhand smoke—particularly in the workplace, in the home, and (for infants) through prenatal exposure. Prevention and treatment can also lead to reduction in the number of injuries and deaths resulting from the leading type of fatal fires: fires caused by cigarettes.7

Smoking also imposes an enormous economic burden on society. The societal costs of death and disease resulting from use of tobacco exceed $100 billion annually.8 Americans spend an estimated $50 billion annually on direct medical care for smoking-related illness.8 Lost productivity and forfeited earnings totaling another $47 billion per year result from smoking-related disability.8 Smoking-related health care costs in California alone total more than $8.6 billion per year.9 Smoking cessation efforts can save years of life at a very low cost compared with alternative preventive interventions. Tobacco-cessation counseling is more cost-effective than other common, covered disease-prevention interventions (eg, screening for hypertension and high blood cholesterol levels10 and periodic mammo-graphic screening for breast cancer). Cost analyses have shown that the benefits of tobacco-cessation efforts are either cost-saving or cost-neutral.11,12 The cost of providing a comprehensive tobacco-cessation benefit ranges from 10 to 40 cents per member per month (costs vary on the basis of both medical utilization and coverage for dependents).13,14 In contrast, the annual health care cost of tobacco use is about $3400 per smoker.1 Internal analysis of the cost-benefit scenario for cessation program coverage showed that although the enhanced benefits require initial investment, the plan results in savings (ie, due to improved health outcomes) within six years.

According to Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence,3 a clinical practice guideline released in June 2000 by the US Public Health Service (PHS), efficacious cessation treatment for tobacco users is available and should become a part of standard medical practice. Tobacco-dependence treatment and prevention is a high priority for KPNC. Tobacco Counseling became a regional quality goal in 2001, linking performance on this goal to incentive pay for physicians.

Relevance for Direct Patient Care

Development and implementation of the Tobacco Dependence Program has led to improved patient care. Specifically, this improvement was achieved through several clinical and operational changes:

At all clinic visits in primary and specialty care departments, routine assessment of tobacco use status, giving advice to quit, and referrals to cessation programs

For members enrolled in any of our tobacco cessation programs, enhancing health plan benefits covering unlimited attendance at smoking-cessation classes for no additional cost and covering cessation medications for a copay

Making KP campuses smokefree to decrease members' potential exposure to environmental tobacco smoke while visiting KP facilities

Increasing patient satisfaction by assessing them for tobacco use and advising smokers to quit

Increasing the awareness of KP physicians and other medical staff that clinicians have an important role in encouraging patients to stop smoking

Regularly communicating performance feedback (ie, quarterly) to Department Chiefs and staff.

Research consistently has shown that brief advice to quit smoking, delivered to patients from their medical practitioners, increases patient satisfaction and increases quit rates a mean of 30%.14,15

Program Innovation and Leadership

The Tobacco Dependence Program is unique because of its scope, clinical outcomes, and sustainability. Best practices used by the program include its multi-faceted nature, which combines clinician training, audit, and incentive-linked feedback and enhancement of coverage for cessation aids and for health education programs as well as support for tobacco control efforts in the workplace and in the community. KPNC has led the health care industry in implementing evidence-based Public Health Service recommendations. We have shared our best practices with other KP Regions and with external agencies. The success of the Tobacco Dependence Program is due largely to the collaborative efforts of many different leadership groups and departments within KP.

Measures Used to Assess Quality of the Program

To evaluate its impact and effectiveness, the program measures five indicators:

Advice to quit smoking, measured by the KP Member and Patient Survey (MPS)

Rates of advising smokers to quit, measured by the HEDIS Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Survey (CAHPS)

Prevalence of tobacco use, attendance at cessation programs, and use of nicotine replacement therapy, all measured by the Member Health Survey

Prescriptions for nicotine replacement products, recorded in the Pharmacy Information Management System (PIMS)

Attendance at tobacco cessation programs, recorded in the Regional Health Education Group Class Report Database.

Measurement Instruments used by the Program

For data collection and analysis, the Tobacco Dependence Program utilizes five retrospective measurement instruments: The MPS, the CAHPS, the Member Health Survey, PIMS, and the Group Class Database.

The MPS tracks patients' satisfaction with medical services and access. The survey sample consists of a daily stratified random sample of patients who receive a survey in the days following an office visit. The patient survey has a target of 100 surveys per physician or other health care practitioner per year. A 48% response rate yields approximately 105,000 patient surveys each quarter. The question pertaining to Physician Advice to Quit Smoking asks, “If you smoke, were you advised to quit by Dr X during your last visit?” Answer options are: Yes, No, I Don't Smoke, I Don't Remember. Survey results for this measure are reported as members who answered “Yes” (numerator) divided by those who answered “No,” “I Don't Smoke,” or “I Don't Remember” (denominator). The results are reported quarterly as an average over a rolling four-quarter period. The internal long-term (three-year) goal for this measure is a 65% rate of giving advice to quit smoking by 2005.

The success of the Tobacco Dependence Program is due largely to the collaborative efforts of many different leadership groups and departments.

HEDIS uses CAHPS, a written survey administered to adult Health Plan members who were continuously enrolled during the reporting year and who were either current smokers or recent quitters. The survey asks whether the member received smoking-cessation advice from a Health Plan clinician during the reporting year. A “current smoker” is defined as someone who has ever smoked 100 cigarettes and who smoked either on some days or on every day during the past year. A “recent quitter” is defined as someone who has ever smoked 100 cigarettes and who stopped smoking during the past 12 months. The CAHPS survey sample includes between 400 and 500 Health Plan members per year per Health Plan. The NCQA uses this HEDIS survey to set benchmarks for quality in health care organizations and to measure their performance. The national benchmark set by NCQA on the Advising Smokers to Quit (ASTQ) measure is the 75th percentile (currently 71.5%).

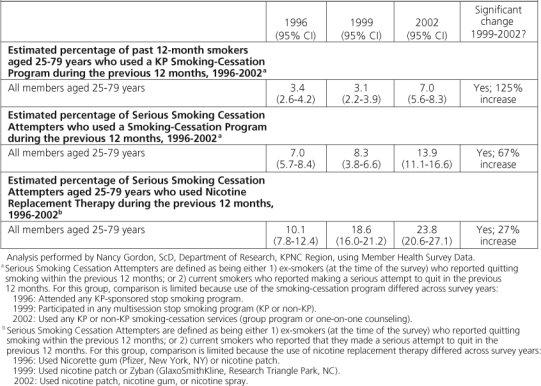

The KP Member Health Survey provides estimates of the percentage of current smokers in the KPNC member population as well as data on their attendance at smoking-cessation classes and use of cessation medication (nicotine replacement therapy). These estimates are based on respondent data weighted to the age-sex distribution of the medical center service population (hospital and outpatient clinics). The KP Member Health Survey is a mailed questionnaire survey that is conducted in the spring of every third year (most recently 1996most recently 1999, and 2002). The survey is mailed to a stratified, random sample of 40,000 adult KPNC members. The external benchmark for this measure is that of Healthy People 2010,2 ie, an adult tobacco use prevalence of <12% by 2010.

To measure use of smoking-cessation medication before and after the changes in Health Plan benefits, data on nicotine replacement were extracted from PIMS for the first, second, and third quarters of 2002 and 2003. Because KPNC members may buy the nicotine patch over the counter at non-Kaiser pharmacies and at retail drug stores, these data underestimate the true number of cessation medications used before and after the benefits enhancement.

The Group Class Database collects data on attendance at smoking-cessation classes. Because of changes in reporting procedures, class attendance data reported before 2002 cannot be validly compared with class attendance data reported after 2002. To measure the effect of benefits enhancement on program attendance, attendance at a representative sample of KP facilities using the same attendance reporting procedure was compared for the first three quarters of both 2002 and 2003.

Results

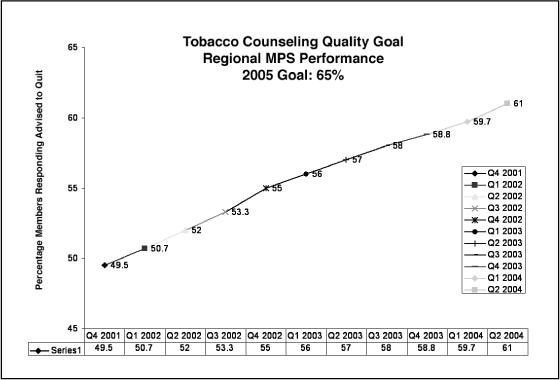

Results of the Member and Patient Survey show a dramatically positive trend in KPNC rates of giving members advice to quit smoking: From the fourth quarter of 2001 to the second quarter of 2004, rates increased by 23% (Figure 3).15,16 Both the MPS and HEDIS measures rely on patient recall, and recall error is often a weakness in data collection.

Figure 3.

For KPNC members visiting KPNC facilities since inception of the Tobacco Dependence Program, graph of responses to Member and Patient Survey shows increase in rates of being advised by clinicians to stop smoking.

“… [m]ore intensive tobacco dependence treatment is more effective than brief treatment. Also, it should be noted that intensive interventions are appropriate for any tobacco user willing to participate in them.”2:p37

In this case, however, patient recall improves the quality of practice by necessitating the giving of memorable advice. Because the MPS is both mailed and received several days after a visit, a positive response to the survey provides a good indication that the health care practitioner gave clear, strong, personalized advice—the type of smoking-cessation advice recommended in the US Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guidelines.

The HEDIS rates also consistently improved over the course of the program: These rates increased by 32% from 1998 to 2003 (Figure 2). Currently, KPNC rates far exceed the 75th percentile benchmark set by NCQA and are within a point of the 90th percentile. These results show how the Tobacco Dependence Program's comprehensive approach to tobacco dependence and prevention has led to success above and beyond secular trends in the general population. In 1998, KPNC's performance on the HEDIS Advising Smokers to Quit measure was one of the lowest of all the KP Regions, ranking 7th among the eight regions (Northern California, Southern California, Colorado, Georgia, Mid-Atlantic, Hawaii, Northwest and Ohio). By 2004 (reporting year 2003), KPNC ranked second place among the other eight KP Regions. The California Cooperative Healthcare Reporting Institute reported that KPNC outperformed all other California commercial HMOs on the ASTQ measure in 2003.17

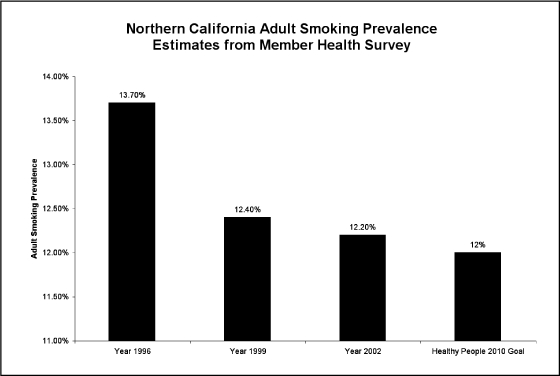

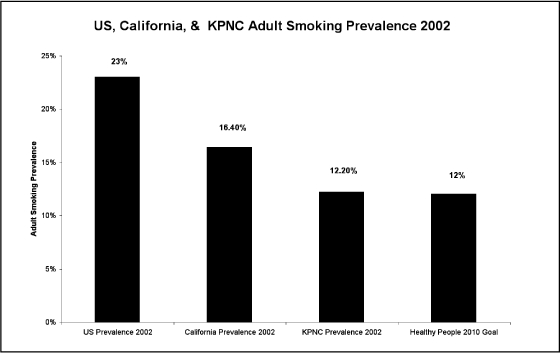

As shown by results of the past three Member Health Surveys, prevalence of tobacco use among KPNC members has decreased by 10.9% (Figures 4,5). At a prevalence of 12.2%, KPNC is approaching the Healthy People 2010 prevalence goal of ≤12%. Although these data show a positive trend for tobacco cessation, external factors may influence prevalence of tobacco use; therefore, we cannot state with certainty that the Tobacco Dependence Program is the sole cause of the trend.

Figure 4.

Graph of responses to KP Member Health Survey shows that the significantly reduced prevalence of smoking observed among adult KP members is close to meeting the Health People 2010 goal for smoking cessation.

Figure 5.

Graph shows prevalence of smoking observed among adult KPNC members (shown also in Figure 4) compared with prevalence of smoking observed in the general US population, prevalence observed in the general California population, and prevalence set as a Health People 2010 goal for smoking cessation efforts.

The number of smokefree KP campuses has increased …

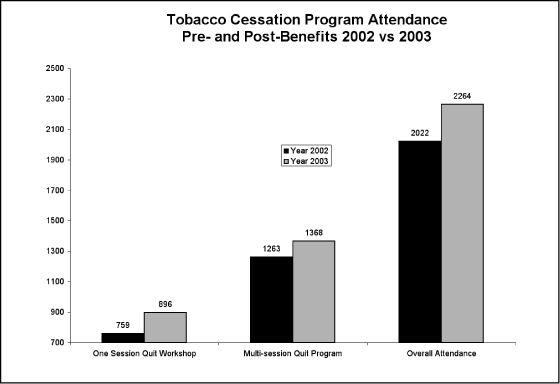

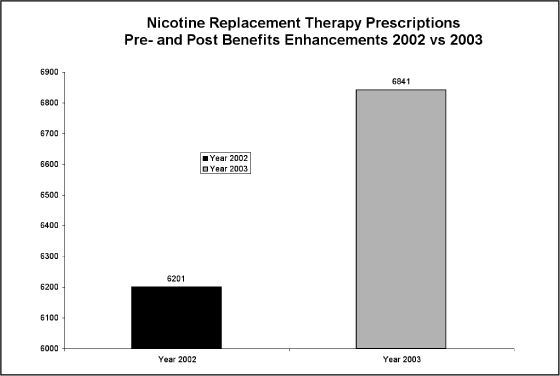

After Health Plan benefits were enhanced to provide more coverage for smoking-cessation aids, positive trends were seen in prescriptions for cessation medication and in attendance at tobacco-cessation classes. Comparison of the preenhancement and postenhancement survey results showed an overall increase of 12% in cessation-program attendance and an overall 10.3% increase in prescriptions for nicotine replacement therapy. These successes occurred despite a reduction in KPNC membership—a decrease of 100,000 members—during the timeframe examined (Figures 6,7; Table 1). The Member Health Survey further points to a dramatic rise in use of tobacco cessation programs and medications. Because of limitations in the data and the lack of a control group, however, these trends cannot be interpreted definitively.

Figure 6.

Graph shows increase in overall attendance at KPNC smoking-cessation programs since these programs became a covered benefit for KPNC members.

Figure 7.

Graph shows increase in prescriptions for nicotine replacement therapy among KPNC members since these prescriptions became a covered benefit with a copay.

Table 1.

KPNC Tobacco Dependence Program contributors

Table 2.

Results of the three most recent KP member health surveys distributed to adult Kaiser Permanente Northern California Region members

The number of smokefree KP campuses has increased over the life of the Tobacco Dependence Program. Before 1998, no KP campus was completely smokefree, whereas 16 campuses had become completely smokefree as of August 2004. The remaining campuses have restricted smoking to minimal outdoor areas or to a single outdoor shelter. The Tobacco Dependence Program has also met its objectives of contributing to community tobacco control efforts and supporting tobacco control policy.

… the health and economic burden of tobacco dependence is still too great …

Conclusions

Because of the multitude of competing health priorities, health care systems face a special challenge when trying to maintain and improve prevention efforts. KPNC believes that the health and economic burden of tobacco dependence is still too great and that the usual methods of relying on self-help and self referral are inadequate to significantly improve the health of our members. We hypothesized that prevalence of tobacco use would be reduced by a multifaceted systems approach to tobacco-use cessation and prevention. The Tobacco Dependence Program has achieved extraordinary success achieving our objectives: increasing the rate of physicians giving patients advice to quit smoking; increasing attendance at tobacco-cessation classes and prescriptions for cessation medications; increasing the number of smokefree KP campuses; and supporting community and legislative policies promoting control of tobacco use. We have almost reached our objective of meeting the Healthy People 2010 goal of ≤12% prevalence of tobacco use in our KPNC membership population. Program sustainability has depended on fully integrating tobacco-use assessment and referrals and a strong infrastructure of effective, covered tobacco cessation programs and medications into routine medical practice. Inclusion as a Quality Goal (ie, providing for internal monitoring of our performance on “Advising Smokers to Quit”) has allowed the program to continue improving and growing throughout KPNC, reaching all primary care and specialty departments by the end of 2004. Quarterly feedback reports reinforce positive performance and motivate departments that are not performing as well as they could. Ongoing executive and medical center leadership support also has been an important factor in our success. Although we believe that we have been exceptionally successful in our approach to reducing tobacco dependence, we also believe in the importance of providing ongoing support to our tobacco dependence efforts. It is important to continue advocating for support for tobacco dependence treatment within the organization. In this regard, we continue to provide training to staff, work for full integration across program areas, make the best use of internal data, maintain and improve our health education programs, and develop systems that assist staff with advice and referral.

“Pharmacotherapies such as bupropion SR or nicotine replacement therapies consistently increase abstinence rates.”2:p38

Transferability

Having been successfully integrated throughout KPNC, the Tobacco Dependence Program, has shared its systems and education tools with other KP Regions. The Program contributed best practices to the 1998 Tobacco Cessation Implementation Kit developed by the Care Management Institute. The KPNC Smoking as a Vital Sign process was used as a model for the California Tobacco Control Alliance's “Health Care Providers Toolkit for Delivering Smoking Cessation Services.”18 As an example of best practices, the Program has shared the single-session Quit Tobacco Workshop curriculum with The American Legacy Foundation Community Voices Tobacco Initiative (a nationwide network of tobacco-control and health agencies working to reduce prevalence of tobacco use in medically underserved populations) and the National Association of City and County Health Officials. KPNC's enhanced benefits for cessation programs and medications have also provided a model for other KP Regions. The KP Southern California Region has since adopted a similar benefit structure for their tobacco cessation programs and medications. For KP Regions which have implemented KP HealthConnect, smoking status is recorded as part of the process of monitoring vital signs. Advice to quit smoking can be included as part of the patient instructions section of the after-visit summary by using smart phrases. KP HealthConnect will not replace the need for physician communication and treatment options training or performance audit and feedback. Although the KPNC Tobacco Dependence Program has successfully shared much of its contents, more work can—and should—be done to transfer best practices for creating and integrating a multi-faceted systems approach to reducing tobacco prevalence within a health care system.

Team Involvement and Multidisciplinary Collaboration

Development and implementation of the Tobacco Dependence Program involved a multidisciplinary team spanning a range of departments and committees throughout the KP organization and included:

Regional Health Education and Prevention provided vision and leadership.

Department of Research provided and analyzed data on prevalence and benefits.

Executive Leadership provided support in making Advice to Quit a quality goal that raised the visibility of the effort and tied it to incentive pay; also provided support for change to policy of smokefree KP campuses.

Health Plan Benefits made tobacco-cessation classes a covered benefit.

Pharmacy and Therapeutics enabled cessation medications to be available for a copay by members who attended approved behavioral interventions.

Physician Chiefs groups provided consultation on development of program materials and evaluation.

Quality and Operations Support provided leadership for developing the Tobacco Counseling Quality Goal.

Service Quality Research provided internal measurement data and analysis for physician audit and feedback.

Tobacco Dependence Task Force and Physician-Champions facilitated implementation, adapted the program for local needs, and provided leadership at the local level.

Process Development and Change: Routine Tobacco-Use Assessment, Counseling, and Referral

In 1998, Smoking as a Vital Sign (SVS) was implemented in the primary care outpatient clinics of KPNC and has since been integrated into other existing care delivery programs, such as the Chronic Conditions Management program, the Early Start Perinatal Substance Abuse program, and specialty care departments. A process was put in place to identify tobacco users and to offer them advice to quit and referral to smoking-cessation programs. When checking patients' vital signs, the medical assistants screen all patients for tobacco use and document their tobacco-use status on the medical record. The medical record is flagged with a smoking cessation flier and/or magnet if the patient is a current tobacco user. This documentation and flag prompts the medical practitioner to give the patient advice to quit and referral to cessation programs. Advice is then documented on the medical record. The Health Education Department has supported this effort through:

clinician training

supplying implementation tools (eg, self-inking stamps; charts with a section for documenting smoking; posters; pens and lanyards imprinted with the message “Give Advice, Save a Life” or “Smoking as a Vital Sign—Ask and help save a life”)

eliciting support from the physicians' department chief and nurse-manager.

Clinician Training and Performance Feedback

The Tobacco Dependence Program has provided ongoing education and feedback to physicians and other clinical staff about the importance of assessing tobacco status in addition to feedback on their performance in regard to advising smokers to quit. This feedback communication has occurred through regular quarterly communication of performance feedback to Department Chiefs and Managers. The Tobacco Dependence Program thus strives to develop innovative methods to improve advice rates. In 2003, for example, the Tobacco Dependence Program provided every KP facility with an “Oscar” trophy to award each quarter to high-performing departments on a rotating basis. Performance feedback and introduction of healthy competition have resulted in an overall increase in awareness among physicians and other medical staff about the clinician's role in encouraging patients to stop smoking.

A Variety of Tobacco-Cessation Programs for KP Members

KPNC has provided smoking cessation programs to its members since the 1970s. However, these programs were limited to multisession group classes attended by only a small percentage of current smokers, most of whom referred themselves to the class. Feedback from patients indicated existence of two barriers to member involvement in cessation programs:

the limited types of cessation programs available

the costs associated with those programs.

To reduce those barriers, we expanded our programs to meet the various needs of our members by including not only multisession classes but also individual counseling, single-session workshops, telephone counseling, Breathe (the online, personalized quit-smoking program available through kp.org), tailored information for teens and for pregnant women, and extensive self-help resources.

Enhanced Health Plan Benefits Covering Tobacco-Cessation Programs and Medications

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that health plans provide full coverage for smoking cessation behavioral interventions as well as for pharmacotherapy so that out-of-pocket expenses incurred by patients (including costs for over-the-counter drugs) are minimized—or completely eliminated whenever possible.3 To achieve this standard, The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) Regional Heath Education Department worked closely with the Health Plan Benefits Department to examine the cost of offering tobacco cessation programs as a covered benefit. Patient care was directly improved by enhancing Health Plan benefits to cover unlimited attendance at cessation classes at no additional cost to members. In addition, the Regional Health Education Department developed a protocol jointly with our Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee to allow KP members enrolled in any KP cessation program to receive cessation medication for the price of their copay. A patient education brochure was developed describing the covered benefit for cessation medication and the role of medication in quitting tobacco use. A 14-minute video was created describing all the cessation medications and how they are used.

Worksite Tobacco-Control Efforts: Working with Executive Leadership

Policies mandating a smokefree worksite are well known to reduce environmental tobacco exposure for all KP employees and patients; to reduce employees' daily consumption of cigarettes; to increase rates of quitting smoking; and to reduce the risk of fire.19 This strategy to promote smoking cessation and prevention has been encouraged by development and dissemination of a recommendation that all KPNC medical centers and clinics implement a smokefree-campus policy. The Tobacco Dependence Program worked closely with TPMG Executive Leadership to implement the policy mandating that all KP campuses opening in 2003 and thereafter will be smokefree.

Policies mandating a smokefree worksite are well known to reduce environmental tobacco exposure for all KP employees and patients …

Community Initiatives and Support for Policies Controlling Tobacco Use

The Tobacco Dependence Program has collaborated outside the clinic setting to bring messages of smoking cessation and prevention to the community. In 2004, funded by a Community Grant from the Community Benefit Program, the KPNC Regional Health Education Department partnered with a Bay Area radio station to conduct a six-month antitobacco campaign that targeted teens and young adults. The campaign was recognized by the American Legacy Foundation's Truth Campaign as a successful strategy for communicating a tobacco-control message in a way that reached adolescents and young adults in the surrounding community. The Tobacco Dependence Program has also worked with the KPNC Government Relations Department to support tobacco control legislation, such as California Assembly Bill 221, the Tobacco to 21 initiative.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank many people from the KPNC Region who have contributed to the success of this program—From the KPNC Regional Health Education Department, David Sobel, MD; Nancy Bouffard, MPH, MSW; and Scott Thomas, PhD [currently working with the American Legacy Foundation/Columbia University on tobacco control issues]; from the Quality and Operations Support Department: Susan Bachman, PhD, and Mike Ralston, MD; the Community Benefit Program; the Tobacco Dependence Task Force and Smoking as a Vital Sign (SVS) Physician Champions; Phil Madvig, MD, administrative sponsor. The authors also thank Tim McAfee, MD, MPH, formerly of Group Health Cooperative, Seattle Washington, for conceptual development.

References

- Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs—United States, 1995–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 Apr 12;51(14):300–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Healthy people 2010 [monograph on the Internet] 2nd ed. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [cited 2005 Mar 8]. Available from: www.healthypeople.gov/document/ [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence [monograph on the Internet] Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [cited 2005 Mar 8]. Available from: www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/treating_tobacco_use.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Physician and other health-care professional counseling of smokers to quit—United States, 1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993 Nov 12;42(44):854–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 Jul 26;51(29):642–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trends in cigarette smoking among high school students—United States, 1991–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002 May 17;51(19):410–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JR., Jr. The smoking-material fire problem [monograph on the Internet] Quincy (MA): National Fire Protection Association; 2004. [cited 2005 Mar 8]. Available from: www.nfpa.org/assets/files/MbrSecurePDF/OSSmoking.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott S, Godfrey C. Economics of smoking cessation. BMJ. 2004 Apr 17;328(7445):947–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7445.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Max W, Rice DP, Sung HY, Zhang X, Miller L. The economic burden of smoking in California. Tob Control. 2004 Sep;13(3):264–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings SR, Rubin SM, Oster G. The cost-effectiveness of counseling smokers to quit. JAMA. 1989 Jan 6;261(1):75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner KE, Smith RJ, Smith DG, Fries BE. Health and economic implications of a work-site smoking-cessation program: a simulation analysis. J Occup Environ Med. 1996 Oct;38(10):981–92. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Schauffler HH, Milstein A, Powers P, Hopkins DP. Expanding health insurance coverage for smoking cessation treatments: experience of the Pacific Business Group on Health. Am J Health Promot. 2001 May–Jun;15(5):350–6. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauffler HH, McMenamin S, Olsen K, Boyce-Smith G, Rideout JA, Kamil J. Variations in treatment benefits influence smoking cessation: results of a randomized controlled trial. Tob Control. 2001 Jun;10:175–80. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, McAfee T, Pabiniak C. Use and cost effectiveness of smoking-cessation services under four insurance plans in a health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med. 1998 Sep 3;339(10):673–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis JF, Bills R, Whitlock E, Stevens VJ, Mullooly J, Lichtenstein E. Implementing tobacco interventions in the real world of managed care. Tob Control. 2000;9(Suppl 1):118–24. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_1.i18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg LI, Boyle RG, Davidson G, Magnan SJ, Carlson CL. Patient satisfaction and discussion of smoking cessation during clinical visits. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001 Feb;76(2):138–43. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)63119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Cooperative Healthcare Reporting Initiative. Report to CCHRI participants: 2002 performance results [monograph on the Internet] San Francisco (CA): California Cooperative Healthcare Reporting Initiative; 2003. [cited 2004 Aug 26]. Available from: www.cchri.org/reports/2003%20cchri%20internal%20report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Next Generation, California Tobacco Control Alliance. Health care provider's tool kit for delivering smoking cessation services [monograph on the Internet] San Francisco (CA): Next Generation, California Tobacco Control Alliance; 2003. [cited 2005 Mar 8]. Available from: www.cessationcenter.org/pdfs/NGAToolkit_FINAL_FORWEB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Smoke-free work-places: at a glance [monograph on the Internet] 2002 Jul. [cited 2004 Aug 26]. Available from: http://wbln0018.worldbank.org/HDNet/hddocs.nsf/0/ae1ba5d36733ed0985256bfa0065501e/$FILE/AAG%20SmokeFree%20Workplaces.pdf.