Abstract

Currently, no data from randomized controlled clinical trials are available to guide the depth of resection for intermediate-thickness primary cutaneous melanoma. Thus, we hypothesized that substantial variability exists in this aspect of surgical care. We have summarized the literature regarding depth of resection and report the results of our survey of surgeons who treat melanoma. Most of the 320 respondents resected down to, but did not include, the muscular fascia (extremity, 71%; trunk, 66%; and head and neck, 62%). However, significant variation exists. We identified variability in our own practice and have elected to standardize this common aspect of routine surgical care across our institution. In light of the lack of evidence to support resection of the deep muscular fascia, we have elected to preserve the muscular fascia as a matter of routine, except when a deep primary melanoma or thin subcutaneous tissue dictates otherwise.

Large randomized controlled trials evaluating the extent of surgical resection for primary melanoma have been conducted.1-7 These studies have established level I evidence supporting the current recommendations for the surgical approach to peripheral margins. However, the literature regarding the extent of deep resection is scant, and no consensus has been reached on the extent of deep resection for melanoma. Treatment guidelines such as those put forth by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network8 and the recent Cochrane review9 do not mention this aspect of surgical treatment. Ideally, such a commonly performed procedure should be standardized and evidence based. Currently, no prospective data or results from randomized trials are available to direct this routine surgical procedure for the 68,130 patients anticipated to be diagnosed as having a primary resectable melanoma in 2010.10 As a result, no consensus about the depth of melanoma excisions has been formally established, leading us to hypothesize that considerable variability exists in the surgical approach to primary melanomas. This article reviews the literature, reports the findings of a survey of melanoma surgeons designed to define the current practice pattern regarding the routine depth of excision for intermediate-thickness melanomas (melanomas 1-4 mm in Breslow depth), and offers a Mayo Clinic consensus statement developed on this aspect of care for this patient population.

LOCAL RECURRENCE

Local recurrence is an uncommon event and is widely viewed as a benchmark of surgical quality control. Most local recurrences occur within the first few years after diagnosis but some have been reported as long as 15 years or more later.11 Local recurrence is most likely a manifestation of residual microsatellites in the neighboring tissue left behind after resection.12 In contrast to local recurrences of basal or squamous cell carcinomas that are not life-threatening, a local recurrence of melanoma is associated with a very poor overall survival rate. In the Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial, greater than 85% of patients whose first evidence of relapse was local recurrence died2; in longer follow-up, local recurrence was associated with a 10-year survival rate of 5%.1 One could hypothesize that local recurrences are, in fact, a manifestation of intralymphatic disease, rather than residual primary melanoma cells that grow back with an unusually aggressive biological capacity for metastases. This explanation is a much more logical rationale for why we perform a wide excision of normal-appearing skin surrounding a primary melanoma (ie, to excise microsatellite metastases that usually are not detected without serial sectioning of the primary melanoma).12

Similar to local recurrence, in-transit metastases develop from residual intralymphatic disease left behind after resection or malignant transformation of melanocytes that is not yet associated with phenotypic changes and therefore not appreciated on histological review of the margins. Local recurrence and in-transit metastasis share the same risk factors and prognosis. The typical 2-cm proximity definition to the scar separating the two is merely convenient for classification purposes.

The potential mechanisms for local recurrence are not completely understood and may be related to incomplete resection in some cases and adverse biological features of the primary tumor in most. More aggressive tumor features, including thick primary tumor, ulceration, lymphovascular invasion, location of the primary melanoma, lymph node involvement, desmoplastic subtype, and satellitosis have all been shown to be significant risk factors for locoregional recurrence.11,13-15 Although the presence of dermal lymphatic invasion is an infrequent finding, a review article noted that it was present in most patients who experienced a local recurrence.13 The incidence of lymphovascular invasion is approximately 5% and closely mirrors the 3% to 7% incidence of local recurrence in patients with melanoma.13,16,17 However, the only variable that the surgeon can influence is the histopathologic proximity to the margin.15

Prognosis after recurrence depends on whether the site of recurrence is local, regional, or distant.18,19 Prognosis after locoregional recurrence is largely the result of pathologic features of the original primary melanoma as well as the disease-free interval before recurrence.14,20,21 Most of these patients subsequently develop additional local, lymph node, or distant metastases, each associated with declining 5-year survival (45.4%, 34.3%, and 17.3%, respectively).11 In some cases of local recurrence, operative resection can result in prolonged survival; however, local recurrence is frequently associated with distant systemic disease.

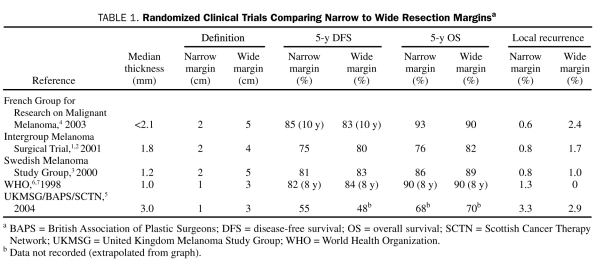

Peripheral Margins

The oncologic adequacy of narrow resection margins vs more traditional wide margins has been compared in 5 randomized controlled trials enrolling 3297 patients with a robust 5- to 16-year median follow-up.1-6 The definitions of narrow and wide margins varied from 1 to 2 cm for narrow margins and 3 to 5 cm for wide margins. The depth of melanoma also varied between studies, from low-risk, thin melanomas (<1 mm) to higher-risk, thick melanomas (>4 mm). None of these studies demonstrated a significant difference between the narrow and wide resection margins in regard to disease-free or overall survival; however, one trial showed a higher locoregional recurrence rate in the narrow-excision group5 (Table 1). Similarly, several meta-analyses showed no significant difference in overall survival, disease-free survival, and in-transit, regional, or local recurrence.9,22,23 No significant difference was noted in overall (hazard ratio, 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.15; P>.05) or recurrence-free (hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% confidence interval, 0.99-1.28; P=.06) survival in the Cochrane meta-analysis for wider margins. A recent meta-analysis evaluated disease-specific survival in the 3 randomized controlled trials (N=2357); the pooled meta-analysis revealed an increased risk of death from melanoma for patients undergoing narrow vs wide surgical excision of their primary melanoma (hazard ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.53; P=.01).24 This improvement came at the expense of increased short-term morbidity and patient dissatisfaction with scar appearance.9 These studies have led to the current widely accepted standard treatment guidelines supported by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, which recommend 1-cm margins for thin melanoma (<1-mm thick), 1- to 2-cm margins for 1- to 2-mm melanomas, and 2-cm margins for intermediate-thickness melanomas (2-4 mm).

TABLE 1.

Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Narrow to Wide Resection Marginsa

Moreover, nearly all of the prospective and retrospective studies regarding margin of excision for melanoma have used gross margins determined by the surgeon. Only the 2005 study by McKinnon et al15 examined the relationship of the histological margin with recurrence.15 Their definition provides a more accurate measurement of the closest radial margin of normal tissue from the leading peripheral edge of the tumor. A histological radial margin of less than 0.8 cm is associated with a significant increase in locoregional recurrence. Microscopic margins greater than 0.8 cm did not further decrease locoregional recurrence. McKinnon et al15 correlated this to a 1-cm gross margin, accounting for an approximately 20% correction for tissue shrinkage after histological processing. Unfortunately, the histopathologic proximity to the margin can only be determined after resection, and therefore the gross margin continues to guide surgical resection.

Deep Margins

The ideal depth of excision is unknown because there is a paucity of data regarding this aspect of surgical care. Only 2 retrospective studies could be identified that attempted to directly address the extent of deep resection, specifically excising the deep muscular fascia, and the effect on outcome. The first report by Olsen,25 published in 1964, was a review of 112 patients undergoing surgery between 1949 and 1960. The wide local excision in this study varied from 3 to 50 mm, and regional lymph node dissection was performed in some patients. Although 31 patients who underwent surgery before 1958 had their fascia excised and 14 (45%) developed regional metastasis, regional nodal disease was observed in only 5 (14%) of the 36 patients without the fascia excised. Because no difference in local recurrence was appreciated (10% vs 6%), Olsen elected to proceed with wide local excision, sparing the muscular fascia, beginning in 1958. In the 36 patients in the Olsen study who underwent surgery after 1958, only 2 (6%) developed regional lymph node metastasis. Of the 4 patients who developed local recurrence after excision of the fascia, 3 (75%) subsequently developed lymphatic metastasis; however, none of the 4 patients with local recurrence after resection with the fascia intact developed lymphatic metastasis. Olsen concluded that the deep fascia serves as a barrier to lymphatic but not local recurrences.

Prior to Olsen's study, the fascia of patients with melanoma was routinely excised at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. However, that practice changed in 1969 after Olsen's postulation of a lymphatic barrier function of the underlying fascia. A study by Kenady et al26 enrolling 202 patients with stage 0 and 1 melanoma treated between 1961 and 1974 at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center found no significant differences in the rates of local and regional recurrence between patients in whom the fascia was excised (2.8% and 19.6%) and those in whom it was left intact (5.3% and 25.3%). On the basis of their findings, Kenady et al also concluded that it was unnecessary to excise the deep fascia during resection of melanoma.

Unfortunately, the large prospective trials conducted to define the appropriate radial margins did not standardize the depth of excision. Specifically, 4 of the 5 randomized controlled trials allowed the excision to extend down to or include the deep fascia. As stated in the report of the Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial, “excision of the muscular fascia beneath the melanoma was optional.”2 The randomized controlled trial conducted by the World Health Organization did not describe the depth of excision in the Methods section. During the past several decades, the peripheral margin of primary melanoma excision has become more conservative; however, the optimal depth of excision remains unknown. Melanoma staging (T stage) is based on Breslow thickness (measured in millimeters of penetration from the granular layer of the epidermis), not the size of the lesion, and this remains one of the major prognosticators of a primary melanoma. Because tumor thickness has been associated with local, regional, and distant recurrence, it would seem intuitive that the anatomic depth of surgical resection and the microscopic deep margin status would influence local recurrence. However, no strong evidence currently suggests a given depth at which local recurrence becomes less likely.

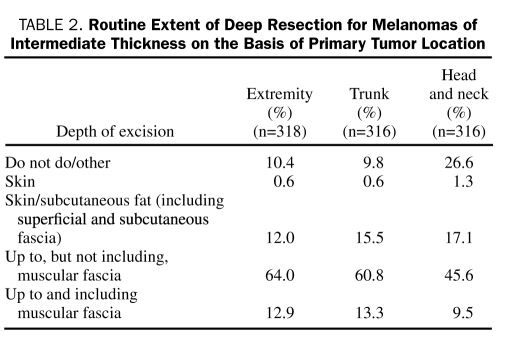

CURRENT NATIONAL PRACTICE

We conducted a survey of surgeons operating on patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas to attempt to define the current practice pattern. This survey was distributed through the American College of Surgeons weekly newsletter, ACS NewsScope. The completed surveys were returned electronically to the Mayo Clinic Survey Research Center for tabulation and analysis. Of the 320 respondents currently practicing and caring for patients with melanoma, 126 (39%) classified themselves as general surgeons and 126 (39%) as surgical oncologists; the remaining respondents were plastic surgeons (34 [11%]), otolaryngologists (12 [4%]), orthopedic surgeons (6 [2%]), or other (16 [5%]). The most common surgical technique reported was resection down to, but not including, the muscular fascia. This was the standard depth of excision for all disease sites (extremity 70.6% [204/289], trunk 66.2% [192/290], and head and neck 61.5% [144/234]), as shown in Table 2. Depth of excision varied by specialty. Surgical oncologists were more likely than the other groups to perform a deep resection as a standard part of their practice (27 [21.4%] vs 10 [8.1%] of general surgeons; P=.004).

TABLE 2.

Routine Extent of Deep Resection for Melanomas of Intermediate Thickness on the Basis of Primary Tumor Location

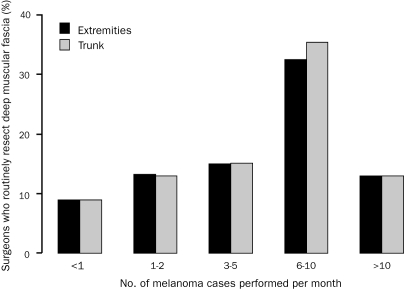

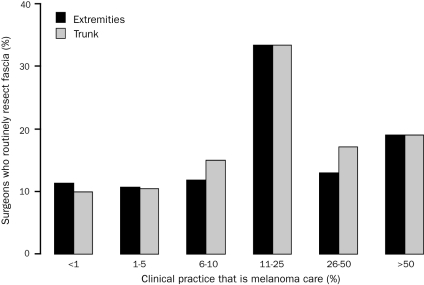

There was no difference in the surgical approach regarding depth of melanoma excision on the basis of academic/university or private practice (P=.61). The number of years in practice also did not correlate with the type of surgical resection (P=.81). Of the respondents who perform less than 1 melanoma procedure in an average month (127 [39.7%]), few routinely resect the muscular fascia for extremity (10 [9.0%]) and truncal (10 [8.9%]) melanomas. In contrast, surgeons performing more than 5 melanoma cases in a month routinely resect the fascia for extremity (14 [22.6%]; P=.03) and truncal (15 [24.2%]; P=.02) melanomas (Figure 1). Similar findings were noted when correlating depth of resection with percentage of practice devoted to melanoma (Figure 2). Of survey respondents who operate on melanoma of the trunk and extremity, most (200 [62.5%]) reported melanoma constituting 5% or less of their surgical practice, and only 44 (13.8%) reported that melanoma made up 25% or more of their practice. A larger melanoma surgical volume and increasing percentage of practice focused on melanoma both correlated with a higher likelihood of performing a routine resection that included excision of the deep muscular fascia.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of surgeons who routinely resect deep muscular fascia stratified by the number of melanoma cases performed in an average month. For extremity melanomas: Overall (extension of Fisher exact test for ordered contingency tables), P=.03; <6 melanoma cases/mo vs ≥6 melanoma cases/mo (χ2), P=.03. For truncal melanomas: Overall (extension of Fisher exact test for ordered contingency tables), P=.02; <6 melanoma cases/mo vs ≥6 melanoma cases/mo (χ2), P=.01.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of surgeons who routinely resect fascia stratified by percentage of clinical practice devoted to melanoma. For extremity melanomas: Overall (extension of Fisher exact test for ordered contingency tables), P=.08; <10% melanoma care vs ≥10% melanoma care (χ2), P=.01. For truncal melanomas: Overall (extension of Fisher exact test for ordered contingency tables), P=.02; <10% melanoma care vs ≥10% melanoma care (χ2), P=.005.

The survey illustrates that, in the absence of an evidence-based standard, the spectrum of care delivered varies widely. It should be noted that most surgeons, regardless of the volume of melanoma cases they handle, do not routinely resect the deep fascia. However, different patterns of care emerged. A higher percentage of high-volume melanoma surgeons routinely resect the deep muscular fascia for intermediate-thickness melanomas of the extremities and trunk compared with lower-volume surgeons. This correlation between surgical volume and extent of deep resection was not seen in head and neck melanomas.

Recently (since the submission of our manuscript for review), DeFazio et al27 reported the findings of their survey of 498 dermatologists caring for patients with melanoma. Survey results showed significant practice pattern differences: nondermatologists routinely resected more deeply than either specialist or nonspecialist dermatologists. Most dermatologists excised into the subcutaneous tissue or down to the fascia but did not include the fascia. The percentage of dermatologists who excised fascia increased as the Breslow depth of the melanoma increased.

LIMITATIONS

Evidence-based data are lacking regarding the recommended depth of resection for excising primary melanomas. Standard surgical resections are based on gross measurements for peripheral extent and anatomic boundaries for depth of excision. Pathology reports are standardized to mention whether the lateral (peripheral) margins are positive or negative and whether they are close, including the distance of the tumor from the margin. The proximity of the tumor to the uninvolved deep margin is not consistently documented. Furthermore, the low incidence of intermediate-depth melanomas at most centers, the low rate of local recurrence, and the standardization of one approach at many institutions would limit the value of single-institution retrospective reviews to investigate this relationship between the depth of clearance and recurrence rate. Because local recurrence is a poor prognostic feature,1,11 understanding whether a relationship between depth of excision and local recurrence exists would be beneficial. Perhaps local recurrence could be affected by surgical technique in this manner. However, the depth of excision may not be relevant as long as a negative margin is obtained, and biological factors alone may be the major determinant of local aggressiveness. A genetic field defect could exist at the leading edge beyond the histological tumor. If so, in the future, excision of these genotypically altered cells could provide an individualized biological basis for the extent of resection.

The definitive method to determine the necessary depth of margin excision would be a prospective randomized trial with long-term follow-up that compared, as a primary end point, rates of locogregional recurrence in patients in whom the deep muscular fascia was resected vs those in whom it was left intact. However, on the basis of the incidence of melanoma and the low prevalence of local recurrence,14,18,19 such a trial would require a large cooperative group approach. To detect a difference of a 3% vs a 6% rate of local recurrence with 80% power at a significance level of .05, 814 patients per group would be required using a 2-sided t test or 655 patients per group using a 1-sided t test. In the current climate of limited research dollars, the resources necessary to definitively answer such a question are unfortunately better spent addressing other more pressing issues for this disease. Recognizing this reality, we conducted the previously described survey to define the current practice pattern. Our study is limited by the very nature of its methodology. All surveys are biased by who receives the survey and who chooses to respond, and these biases likely influenced the results. Although we received a large number of responses, it is impossible to know how many surgeons operate on intermediate-thickness melanomas and whether our findings are truly reflective of current practice. Our data cannot provide a definitive recommendation on what is most oncologically appropriate. This survey is descriptive of the current “spectrum of care” and is not intended to mandate a “standard of care.”

MAYO CLINIC CONSENSUS

An internal query at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, revealed a 50:50 split between surgeons resecting the muscular fascia as a routine and those resecting down to, but not including, the muscular fascia. This variability of care delivered at our institution was deemed to be less than ideal. Many of us have been trained to routinely excise the muscular fascia. Because we have extensive experience managing local recurrence, this more aggressive approach has been performed in an effort to minimize such an outcome. In addition, excising the fascia was thought to be simple and to add little morbidity. However, except for some cases of poor surgical technique, tumor biology and not a positive deep margin likely dictates the natural history of this disease, including local recurrence.

In March 2011, we elected to standardize our practice to ensure that all patients treated at our center receive the same level of surgical care regardless of which surgeon they are scheduled to see. This recommendation has since been endorsed by all 3 Mayo sites (Mayo Clinic's campuses in Rochester, MN; Scottsdale, AZ; and Jacksonville, FL). For primary, intermediate-thickness melanomas of the trunk or extremity, we have elected to routinely resect down to, but not include, the muscular fascia (unless in an area of very thin subcutaneous tissue) until such time as evidence-based guidelines become available.

CONCLUSION

Most of the respondents to our survey of melanoma surgeons routinely resect down to, but do not include, the deep muscular fascia when excising a primary melanoma of intermediate thickness. However, 29.4% of respondents who operate on intermediate-thickness melanomas of the extremity resect to a different level. Similarly, for truncal and head and neck melanomas, the percentage of respondents not following this “standard practice” are 33.8% and 38.5%, respectively. Currently, we must practice in the absence of good data, and, as a result, current practice patterns diverge widely. Our survey supported the fact that this aspect of practice is not standardized. The practice pattern at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, with an even 50:50 split between surgeons routinely resecting the muscular fascia and those resecting down to, but not including, the fascia, is further evidence of this divergence. To have a uniform practice and ensure a single standard of care delivered to all patients at our institution, we have reached a consensus that, moving forward, all primary melanomas of intermediate thickness on the extremities and trunk (excluding hands and feet) will undergo a resection down to, but not including, the muscular fascia. This practice guideline is not meant to be rigid; as always, each surgeon will provide the level of care that is deemed best for the patient in each individual situation, such as resecting the muscular fascia in locations where the subcutaneous tissue is very thin.

This common aspect of melanoma care should be standardized and evidence based. It would be ideal to understand whether and how depth of resection influences local recurrence and overall survival. This relationship may be worthy of further research, perhaps examining whether genotypic changes occur at the leading vertical edge and determining how far they extend beyond the histological margin. However, we must also understand that, as demonstrated for peripheral margins, the biology of the tumor is often the key determinant of outcome.15 As Blake Cady28 so eloquently stated in his 1996 presidential address to the New England Surgical Society:

Biology is King, Selection is Queen, and the technical details of surgical procedures are the Princes and Princesses of the realm who frequently try to overthrow the powerful forces of the King and Queen, usually to no long-term avail, although with some temporary apparent victories.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Maureen Zimmermann for assistance with preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Balch CM, Soong SJ, Smith T, et al. Investigators From the Intergroup Melanoma Surgical Trial Long-term results of a prospective surgical trial comparing 2 cm vs. 4 cm excision margins for 740 patients with 1-4 mm melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8(2):101-108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balch CM, Urist MM, Karakousis CP, et al. Efficacy of 2-cm surgical margins for intermediate-thickness melanomas (1 to 4 mm): results of a multi-institutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg. 1993;218(3):262-267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohn-Cedermark G, Rutqvist LE, Andersson R, et al. Long term results of a randomized study by the Swedish Melanoma Study Group on 2-cm versus 5-cm resection margins for patients with cutaneous melanoma with a tumor thickness of 0.8-2.0 mm. Cancer. 2000;89:1495-1501 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khayat D, Rixe O, Martin G, et al. French Group for Research on Malignant Melanoma Surgical margins in cutaneous melanoma (2 cm versus 5 cm for lesions measuring less than 2.1-mm thick). Cancer. 2003;97:1941-1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas JM, Newton-Bishop J, A'Hern R, et al. Excision margins in high-risk malignant melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:757-766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Veronesi U, Cascinelli N. Narrow excision (1-cm margin): a safe procedure for thin cutaneous melanoma. Arch Surg. 1991;126:438-441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cascinelli N. Margin of resection in the management of primary melanoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;14:272-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Bichakjian CK, et al. NCCN Melanoma Panel Melanoma. Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(3):250-275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sladden MJ, Balch C, Barzilai DA, et al. Surgical excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD004835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2010. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/acspc-024113.pdf Accessed March 2, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong XD, Tyler D, Johnson JL, DeMatos P, Seigler HF. Analysis of prognosis and disease progression after local recurrence of melanoma. Cancer. 2000;88:1063-1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balch CM. Microscopic satellites around a primary melanoma: another piece of the puzzle in melanoma staging. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1092-1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Borgstein PJ, Meijer S, van Diest PJ. Are locoregional cutaneous metastases in melanoma predictable? Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:315-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karakousis CP, Balch CM, Urist MM, Ross MM, Smith TJ, Bartolucci AA. Local recurrence in malignant melanoma: long-term results of the multiinstitutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:446-452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McKinnon JG, Starritt EC, Scolyer RA, McCarthy WH, Thompson JF. Histopathologic excision margin affects local recurrence rate: analysis of 2681 patients with melanomas ≤2 mm thick. Ann Surg. 2005;241(2):326-333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cohn-Cedermark G, Mansson-Brahme E, Rutqvist LE, Larsson O, Singnomklao T, Ringborg U. Outcomes of patients with local recurrence of cutaneous malignant melanoma: a population-based study. Cancer. 1997;80:1418-1425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cruse CW, Wells KE, Schroer KR, Reintgen DS. Etiology and prognosis of local recurrence in malignant melanoma of the skin. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;28:26-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dalal KM, Patel A, Brady MS, Jaques DP, Coit DG. Patterns of first-recurrence and post-recurrence survival in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma after sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1934-1942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zogakis TG, Essner R, Wang HJ, Foshag LJ, Morton DL. Natural history of melanoma in 773 patients with tumor-negative sentinel lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1604-1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Essner R, Lee JH, Wanek LA, Itakura H, Morton DL. Contemporary surgical treatment of advanced-stage melanoma. Arch Surg. 2004;139:961-966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Francken AB, Accortt NA, Shaw HM, et al. Prognosis and determinants of outcome following locoregional or distant recurrence in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1476-1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haigh PI, DiFronzo LA, McCready DR. Optimal excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Surg. 2003;46:419-426 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lens MB, Dawes M, Goodacre T, Bishop JAN. Excision margins in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing narrow vs wide excision. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1101-1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mocellin S, Pasquali S, Nitti D. The impact of surgery on survival of patients with cutaneous melanoma: revisting the role of primary tumor excision margins. Ann Surg. 2011;253(2):238-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olsen G. Removal of fascia—cause of more frequent metastases of malignant melanomas of the skin to regional lymph nodes? Cancer. 1964;17:1159-1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kenady DE, Brown BW, McBride CM. Excision of underlying fascia with a primary malignant melanoma: effect on recurrence and survival rates. Surgery. 1982;92:615-618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. DeFazio JL, Marghoob AA, Pan Y, Dusza SW, Khokhar A, Halpern A. Variation in the depth of excision of melanoma: a survey of US physicians. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:995-999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cady B. Basic principles in surgical oncology. Arch Surg. 1997;132(4):338-346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]