Abstract

mRNA localization coupled with translational control is a widespread and conserved strategy that allows the localized production of proteins within eukaryotic cells. In Drosophila, oskar (osk) mRNA localization and translation at the posterior pole of the oocyte are essential for proper patterning of the embryo. Several P body components are involved in osk mRNA localization and translational repression, suggesting a link between P bodies and osk RNPs. In cultured mammalian cells, Ge-1 protein is required for P body formation. Combining genetic, biochemical and immunohistochemical approaches, we show that, in vivo, Drosophila Ge-1 (dGe-1) is an essential gene encoding a P body component that promotes formation of these structures in the germline. dGe-1 partially colocalizes with osk mRNA and is required for osk RNP integrity. Our analysis reveals that although under normal conditions dGe-1 function is not essential for osk mRNA localization, it becomes critical when other components of the localization machinery, such as staufen, Drosophila decapping protein 1 and barentsz are limiting. Our findings suggest an important role of dGe-1 in optimization of the osk mRNA localization process required for patterning the Drosophila embryo.

Introduction

oskar (osk) (FlyBase: CG10901) mRNA localization and translation at the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte are essential for antero-posterior patterning of the embryo, their failure resulting in embryos lacking an abdomen and germline, the so-called posterior group phenotype [1], [2]. During oogenesis, osk is transcribed in the nurse cells and, upon splicing, begins to assemble into ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes that are transported into the cytoplasm and through the actin-rich ring canals of the nurse cells into their sibling cell, the oocyte, where ultimately the RNA is localized at the posterior pole [3]. Through years of genetic and biochemical analysis, proteins involved in osk post-transcriptional regulation have been identified. These include, Drosophila decapping protein 1 (dDcp1) (FlyBase: CG11183) and Me31B (FlyBase: CG4916), whose yeast and mammalian counterparts are components of cytoplasmic granules named Processing bodies (P bodies) [4], [5], [6].

P bodies have been described in many eukaryotes and consist of aggregates of translationally inactive RNPs [7], [8]. The number and size of these dynamic structures depends on the availability of mRNAs not associated with the translational machinery [7], [9], [10]. Proteins of the mRNA degradation machinery, such as Dcp1 and Dhh1, and translational repressors, such as RAP55 and 4E-T, are enriched in P bodies [7], [8]. Although P bodies are conserved structures, their disruption seems to affect neither mRNA decay nor translational repression [6], [11]. It has therefore been proposed that the role of P bodies might be to compartmentalize mRNA decay and translation repression, possibly enhancing the efficiency of these processes [7].

In yeast, the Yjef-N dimerization domain and the prion-like Glutamine/Asparagine (Q/N)-rich domain of two P body components, Edc3 and Lsm4, respectively, are required for P body assembly [11], [12], suggesting that P body formation might be a self-assembly process [7], [13]. However, in higher eukaryotic cells the Yjef-N domain of Edc3 plays only a minor role in P body assembly [14] and the Q/N domain of yeast Lsm4 is not found in its eukaryotic homologues, suggesting that Lsm4 either performs its function by a different mechanism or does not promote P body formation in these organisms. Interestingly, a conserved protein with no homologue in yeast, Ge-1, contains at its C-terminus a Q/N domain that promotes oligomerization of the protein in vitro, and at its N-terminus a WD40 repeat, a domain often involved in protein-protein interactions [11], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Ge-1 can associate with Dcp1 in vitro to enhance decapping activity [15], [16] and Arabidopsis Ge-1 is involved in postembryonic development, by regulating the decapping process [16]. In different eukaryotic cells, Ge-1 knockdown causes P bodies to disappear [15], [16], [17], [19]. While it is clear that Ge-1 plays a critical role in P body formation in cells, its in vivo functions in metazoans remain largely unexplored.

In this manuscript, we describe our experiments aimed at determining the importance and role of Ge-1 in a living organism, Drosophila melanogaster. We show that Drosophila Ge-1 (dGe-1) (FlyBase: CG6181) is an essential gene that encodes a genuine P body component critical for P body integrity in the fly germline. Our in vivo analysis of dGe-1 function in the germline reveals that dGe-1 promotes the assembly of osk transport RNPs and colflaborates with the osk RNP components Staufen (Stau) (FlyBase: CG5753), Barentsz (Btz) (FlyBase: CG12878) and dDcp1 in osk mRNA localization and Drosophila embryonic patterning.

Results and Discussion

dGe-1 is a lethal gene in Drosophila

The dGe-1 locus encodes two transcripts, dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B, which differ only in their 5′ UTRs and are transcribed during oogenesis (Figure 1A and S1A). To address the function of dGe-1 during oogenesis, we generated deletion mutants by imprecise excision of a P element in the locus (Figure 1A). One of these, dGe-1Δ5 is a recessive lethal mutation whose lethality was rescued by transgenic expression of a dGe-1-B cDNA, proving is a lethal dGe-1 allele.

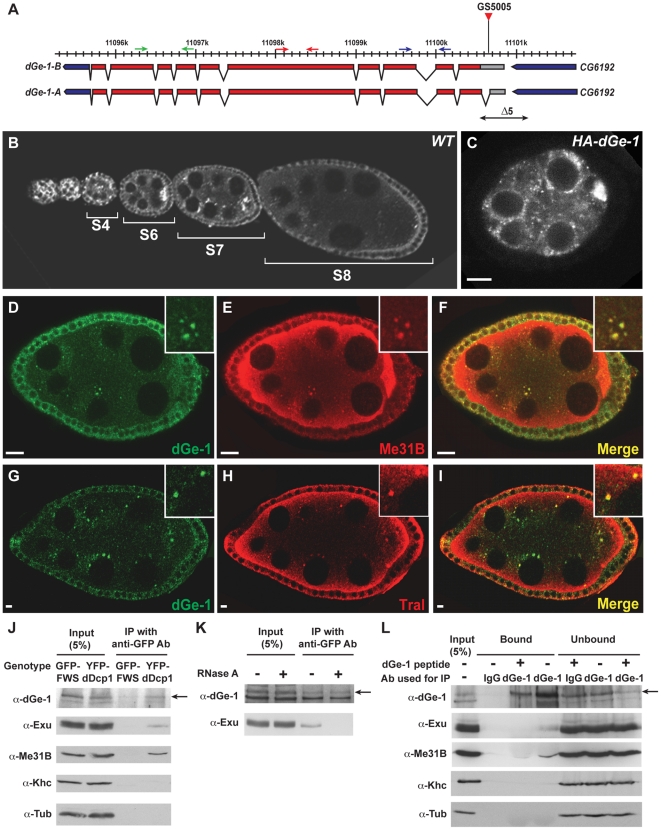

Figure 1. dGe-1 is a P body component in the Drosophila germline.

(A) Scheme representing the dGe-1 locus (polytene band 32D3). Numbers indicate genomic positions along chromosome 2L. 5′UTR, coding region, and 3′UTR: grey, red and blue boxes, respectively. The two dGe-1 transcripts, dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B, the insertion site of the P-element transposon (GS5005, red triangle) used for generation of dGe-1 deletions, and the region deleted in dGe-1Δ5 (double-headed arrow) are represented. Positions of primers used for RT-PCR (Figure S1B) are indicated (blue, red, green arrows). (B) Distribution of dGe-1 protein in wt egg-chambers during early and mid-oogenesis. Immunodetection of dGe-1 using rat anti-dGe-1 antibody. (C) HA-dGe1 protein distribution in wt egg-chamber at stage 6 (S6). HA-dGe-1 detected using mouse anti-HA antibody. (D–I) Colocalization of dGe-1 protein and two P body components. Double-staining of two wt S7 egg-chambers using rat anti-dGe1 (green, D and G) and rabbit anti-Me31B (red, E) or rabbit anti-Tral (red, H) antibodies. Overlays (F and I). (J) Association of dGe-1 and dDcp1 in ovarian extract. Western blot of anti-GFP immunoprecipitates of GFP-FWS and YFP-dDcp1 ovaries. Western blot probed with rabbit anti-dGe-1, anti-Exu and anti-Khc, and mouse anti-Me31B and anti-Tub antibodies. dGe-1 is indicated with an arrow (see legend to Figure 2A). (K) RNA-independent association of dGe-1 and dDcp1. Western blot of anti-GFP immunoprecipitates from YFP-dDcp1 ovarian extract with or without RNase A treatment prior to immunoprecipitation, probed with rabbit anti-dGe-1 and anti-Exu antibodies. dGe-1 is indicated with an arrow. (L) Exu and Me31B associate with dGe-1 in the ovary. Endogeneous dGe-1 protein was immunoprecipitated from wt ovarian extract and bound and soluble fractions were subjected to western blot analysis. Before immunoprecipitation, rabbit anti-dGe-1 was pre-incubated or not with dGe-1 blocking peptide. Western blot probed with rabbit anti-dGe-1, anti-Exu and anti-Khc, and mouse anti-Me31B and anti-Tub antibodies. dGe-1 is indicated with an arrow. Bar, 10 µm.

Analysis of dGe-1Δ5 ovaries requires generation of homozygous mutant dGe-1Δ5 germline clones (GLC) [20]. dGe-1 mRNA levels are dramatically decreased in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries and no trunfcated dGe-1 transcript produced from sequences downstream of the deleted region was detected (Figure S1B). Western blots of extracts of young embryos probed with anti-dGe-1 antibody showed two bands of around 150 kDa, the upper of which was dramatically reduced in extracts of embryos derived from dGe-1Δ5 GLC, indicating that it represents dGe-1 protein (Figure 2A). Hence, dGe-1Δ5 is a strong hypomorphic allele of dGe-1 both at the genetic and the molecular levels.

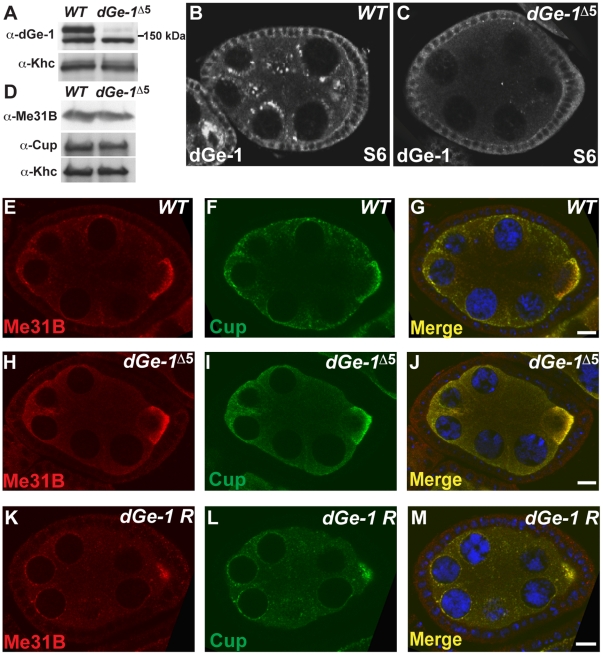

Figure 2. dGe-1 promotes P body formation in the fly germline.

(A) dGe-1 protein levels are strongly reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC. Western blot of dGe-1 protein in extract of 0-2 h wt or dGe-1Δ5 GLC embryos probed with rat anti-dGe-1 antibodies. The band just above 150 kDa, which is dramatically reduced in the mutant extract, represents dGe-1 protein. Khc protein serves as a loading control. (B-C) dGe-1 signal is absent from the nurse cells and oocyte of dGe-1Δ5 GLC. Immunodetection of dGe-1 protein in wt (B) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (C) ovaries using rat anti-dGe-1 antiserum. (D) Western blot analysis of ovarian extracts from wt and dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries, probed with mouse anti-Me31B and anti-Cup antibodies and rabbit anti-Khc antibody. Khc serves as a loading control. (E–K) Immunostaining of wt (E–G), dGe-1Δ5 GLC (H–J) and dGe-1Δ5/dGe-1Δ5; dGe-1 Rescue (dGe-1 R) (K–M) S7 egg-chambers using a rabbit anti-Me31B antibody (E, H, K) or a mouse anti-Cup antibody (F, I, L). Overlays are shown in G, J and M. Bar, 10 µm.

dGe-1 is a P body component in the Drosophila germline

dGe-1 is detected in the cytoplasm of the nurse cells and oocyte in wild-type (wt) ovaries, from early oogenesis onward (Figure 1B), but is absent from these cells in dGe-1Δ5 GLC (Figure 2B–C). dGe-1 is also expressed in the follicle cells surrounding the germline cyst. Both endogenous dGe-1 and transgenic HA-tagged dGe-1 protein are detected in puncta reminiscent of P bodies in the nurse cells (Figure 2B and 1C). Indeed, two P body markers, Me31B and Trailer hitch (Tral, Drosophila homologue of RAP55) (FlyBase: CG10686) [6] colocalize with dGe-1 in puncta (Figure 1D–I). The colocalization of dGe-1 protein with two major P body components suggested that dGe-1 might be a P body component in Drosophila ovaries.

Ge-1 has been shown to associate with Dcp1 in mammalian cells and Arabidopsis [15], [16]. dGe-1, as well as Me31B and Exu (FlyBase: CG8994), a known dDcp1 interactor [4], are selectively enriched in anti-GFP immunoprecipitates from ovarian extract of YFP-dDcp1 expressing flies (Figure 1J), but not from FWS-GFP expressing flies (Four Way Stop (FWS) is a Golgi protein with no known role in mRNA degradation and translation) [21]. Similarly, Me31B and Exu are selectively enriched in dGe-1 immunoprecipitates from wt ovarian extract (Figure 1L). Treatment of the YFP-dDcp1 extract with RNase A prior to immunoprecipitation did not affect the association of dGe-1 with YFP-dDcp1, whereas the association of Exu with dDcp1 is RNA-dependent [4] and was lost (Figure 1K). It therefore appears that, in the ovary, dGe-1 and dDcp1 associate via protein-protein interaction. Taken together, these results indicate that dGe-1, dDcp1, Me31B and Exu are constituents of a shared RNP structure and that dGe-1 is a P body component in the Drosophila germline.

dGe-1 promotes P body formation in the Drosophila germline

To determine if dGe-1 is required for P body formation in the Drosophila germline, we examined the distribution of the P body markers, Me31B and Cup (the Drosophila functional homologue of 4E–T) (FlyBase: CG11181) [6], [22], [23] in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. The overall amounts of these proteins are similar in dGe-1Δ5 GLC and wt extracts (Figure 2D). However the distribution of these proteins is severely affected in the mutant, where they are no longer detected in granules and are uniformly distributed in the nurse cells (compare Figure 2H–J to Figure 2E–G). The granular distribution of Me31B and Cup in dGe-1Δ5 GLC egg-chambers is restored by transgenic expression of a dGe-1-B cDNA (Figure 2K–M). Therefore, as in cultured cells [15], [16], [17], [19], dGe-1 is involved in P body formation in the Drosophila germline.

dGe-1 is involved in osk mRNA localization and embryonic patterning

To understand the role of dGe-1 in mRNA regulation in vivo, we evaluated its association with RNAs in the ovary. All RNAs tested, including the localized RNAs gurken (grk) (FlyBase: CG17610) [24], bicoid (bcd) (FlyBase: CG1034) [25] and osk [26], [27], and the abundant RNAs, tubulin (tub) (FlyBase: CG8308) and ribosomal protein 49 (rp49) (FlyBase: CG7939), were enriched upon dGe-1 immunoprecipitation (Figure S2A), consistent with a general role of P bodies in mRNA regulation.

We next tested if dGe-1 has a role in grk, bcd or osk mRNA localization or translational control. In situ hybridization revealed that bcd and grk localize normally in dGe-1Δ5 GLC (Figure S2B–D, F), although in some oocytes the amount of Grk protein in the antero-dorsal corner appears reduced (Figure S2E and G). Western blot analysis confirmed that Grk protein levels are reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries and embryos (Figure S2H), although no obvious difference in grk mRNA levels was observed by qRT-PCR in dGe-1Δ5 GLC compared to wt ovarian extracts (data not shown). Consistent with this, around 17% of eggs produced from dGe-1Δ5 GLC develop defective dorsal appendages. Importantly, both Grk protein levels and dorsal appendage defects can be rescued by transgenic expression of a dGe-1-B cDNA, demonstrating an involvement, either direct or indirect, of dGe-1 in Grk expression.

In addition, in contrast to wt oocytes (Figure 3A–C), a significant proportion of dGe-1Δ5 GLC oocytes displays defective osk mRNA localization at the posterior pole at stages 9 and 10 (S9, S10) (Figure 3D, 3G and 3J and Figure S3A). This mislocalization, which is rescued by transgenic expression of a dGe-1-B cDNA (Figure S3B–D), is paralleled by defects in Osk protein localization (Figure 3E and 3H), and Osk protein levels are reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries (Figure S3E).

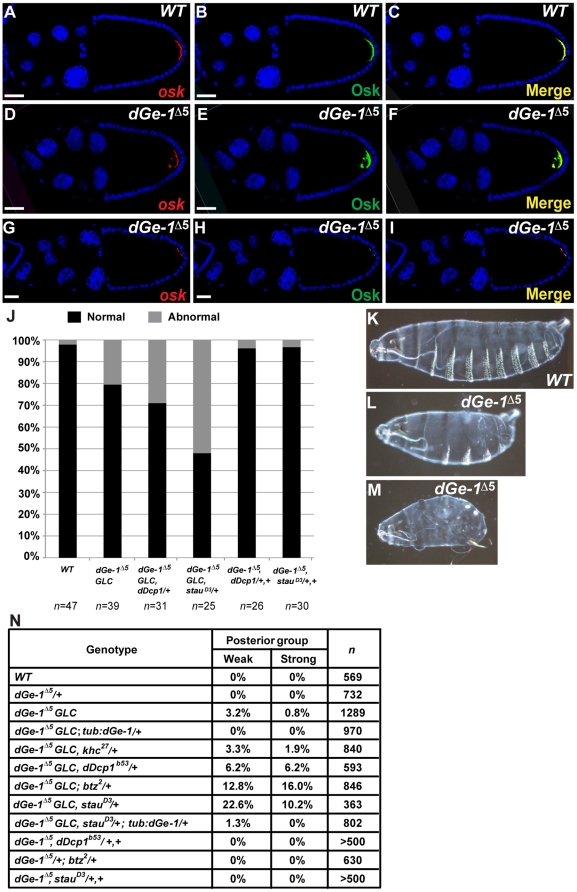

Figure 3. dGe-1 cooperates with Stau and dDcp1 in osk mRNA localization and embryonic patterning.

(A–I) Simultaneous detection of osk mRNA (red) and protein (green) by FISH coupled with immunodetection using a rabbit anti-Osk antibody. osk mRNA (A) and protein (B) colocalize in a posterior crescent at the posterior pole of wt oocytes at S10. (D–I) Examples of the aberrant distribution of osk mRNA and protein in dGe-1Δ5 GLC egg-chambers. Overlays of osk mRNA and Osk protein signals (C, F, I). DNA stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (J) Quantification (%) of osk mRNA localization patterns in S10 egg-chambers in different genetic backgrounds. Normal and abnormal osk mRNA localization are represented as black and grey bars, respectively. n represents the number of embryos analyzed. (K–M) Loss of maternal dGe-1 causes aberrant cuticle patterning in some embryos derived from dGe-1Δ5 GLC. Lateral view of embryos oriented anterior to the left, ventral side down. (K) In a wt embryo, posterior structures represented by the abdominal denticle belts are clearly visible along the ventral side. In a portion of embryos derived from dGe-1Δ5 GLC, several denticle belts are missing (L) and, in extreme cases, all are absent (M). (N) Quantification of posterior group phenotypes produced in different genetic backgrounds. Embryos lacking at least one (weak) or all (strong) abdominal denticle belts were quantified. n represents the number of embryos analyzed. Bar, 50 µm.

Around 55% of the eggs produced by dGe-1Δ5 GLC females develop into embryos and hatch. Among the 45% of the eggs produced by dGe-1Δ5 GLC females that fail to hatch, half (23% of the total) show a normal cuticle. Among the other half, about 16%, presumably unfertilized, develop no cuticle (data not shown). Around 3.2% develop into embryos displaying a weak, and 0.8% a strong posterior group phenotype (Figure 3K–N), consistent with impairment of osk mRNA localization and translation. Another 2.7% develop into embryos showing a variety of patterning defects (such as head open). Importantly, the posterior patterning of dGe-1Δ5 GLC embryos is rescued by expression of a dGe-1-B cDNA in the maternal germline (Figure 3N). These results demonstrate that dGe-1 has a role in abdominal patterning in Drosophila.

dGe-1 interacts genetically with genes involved in osk mRNA localization

To further investigate the involvement of dGe-1 in osk localization, we tested its interaction with other genes involved in the process. Kinesin heavy chain (Khc) (FlyBase: CG7765) is essential for osk transport [28]. Removal of one wt copy of khc did not enhance posterior patterning defects in dGe-1Δ5 GLC embryos (Figure 3N), suggesting that dGe-1 and khc are involved in distinct aspects of osk mRNA localization. Removal of one wt copy of dDcp1, btz, or stau, whose protein products colocalize with osk mRNA and are required for its localization [4], [29], [30], increased the penetrance of the posterior group phenotype among dGe-1Δ5 GLC-derived embryos from 4% to 12.4, 28.8 and 32.8%, respectively (Figure 3N). In contrast, embryos produced by females lacking a copy of dDcp1, btz or stau, but heterozygous for dGe-1 displayed normal abdominal patterning (Figure 3N), highlighting the requirement for dGe-1 in this process. Confirming this, the posterior patterning defects of embryos developing from dGe-1Δ5 GLC heterozygous for stau were fully rescued by a dGe-1-B cDNA transgene (Figure 3N).

We also assayed the genetic interaction of dGe-1 with osk RNP components by assaying osk mRNA localization directly. Whereas heterozygosity for dGe-1Δ5 and dDcp1 or stau did not cause osk mislocalization, loss of both wt copies of dGe-1Δ5 in a dDcp-1 or stau heterozygous background significantly increased the percentage of oocytes with abnormal osk mRNA localization over that of simple dGe-1Δ5 GLC (Figure S3A and 3J). Taken together, these results show that dGe-1 and the osk RNP components cooperate in osk mRNA localization.

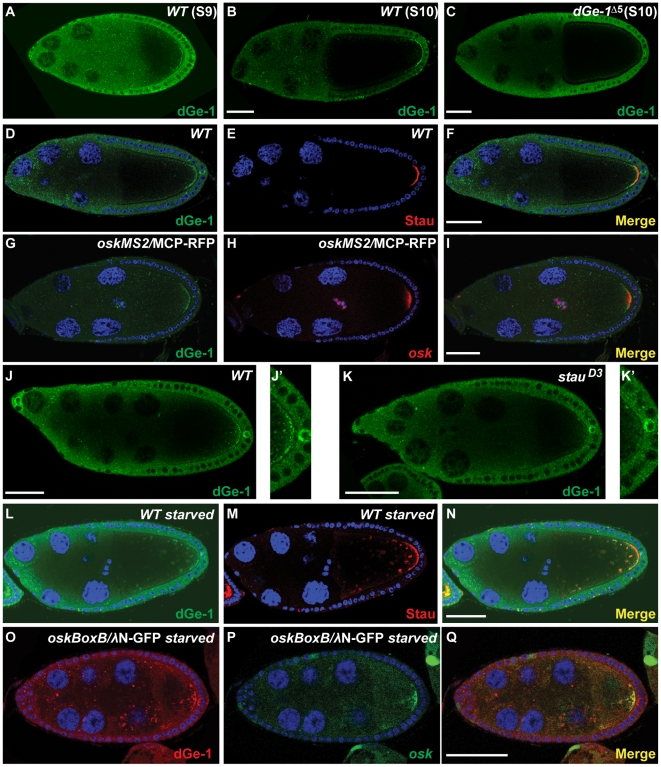

dGe-1 colocalizes with osk mRNA

In addition to its punctate distribution in the nurse cells, dGe-1 protein is also observed in a crescent at the oocyte posterior during mid-oogenesis (Figure 4A–B). This staining is specific, as it is dramatically reduced in dGe-1Δ5 mutant oocytes (Figure 4C). Moreover, the posterior crescent of dGe-1 overlaps with that of Stau, an osk mRNA associated protein, and with osk mRNA (Figure 4D–I), suggesting that dGe-1 protein is a component of osk RNPs.

Figure 4. dGe-1 partially colocalizes with osk mRNA.

(A–C) Immunodetection of dGe-1 protein in wt (A, B) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (C) ovaries using a rabbit anti-dGe-1 antibody. (A, B) In wt ovaries at S9 (A) or S10 (B), dGe-1 protein is enriched at the oocyte posterior pole. (C) The posterior dGe-1 signal observed in wt oocytes (B) is greatly reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC oocytes. (D–F) In a wt egg-chamber at late S9, dGe-1 enriched at the posterior pole of the oocyte (green, D) and partially colocalizes with Stau protein (red, E). The overlay of the two antibody signals is shown in (F). (G–I) Colocalization of dGe-1 protein (green, G) and osk mRNA (red, H) in wt S9 oocytes expressing oskMS2 mRNA and MCP-RFP protein (red, H), to which the RNA is tethered; at S9 oskMS2 mRNA distribution reflects that of endogenous osk mRNA [33]. Overlay of dGe-1 and oskMS2 mRNA signals shown in (I). (J–K) dGe-1 protein staining in wt and stauD3 oocytes. (J, J′) dGe-1 protein is enriched at the posterior pole in wt oocytes. (K and K′) In stauD3 mutant oocytes, which fail to localize osk mRNA, the amount of dGe-1 at the posterior is dramatically reduced. (L–N) Double immunostaining of dGe-1 and Stau proteins in a nutritionally restricted wt egg-chamber. In starved wt oocytes, dGe-1 protein (green, L) is present in large particles, where it colocalizes with Stau protein (red, M). Overlay of dGe-1 and Stau stainings (N). (O–Q) Distribution of dGe-1 protein and osk mRNA in starved wt egg-chambers expressing oskBoxB mRNA and λN-GFP protein, to which the RNA is tethered. In nutritionally restricted wt oocytes, dGe-1 (red, O) is present in large particles, where it partially colocalizes with oskBoxB mRNA (green, P). Overlay of dGe-1 and osk mRNA signals shown in (Q). Bar, 50 µm.

To ascertain if dGe-1 is associated with osk mRNA in vivo, we tested if its distribution in the oocyte depends on osk mRNA. In stauD3 oocytes, which fail to localize osk mRNA [30], posterior localization of dGe-1 is disrupted (Figure 4J–K). Additionally, the osk mRNA and Stau protein aggregates that form upon nutritional restriction of females [31] also contain dGe-1 protein (Figure 4L–Q). Taken together, dGe-1's colocalization with osk mRNA and Stau, as well as its dependence on stau for posterior localization, suggest that in vivo some amount of dGe-1 is associated with osk RNPs.

dGe-1 is required for osk RNP integrity

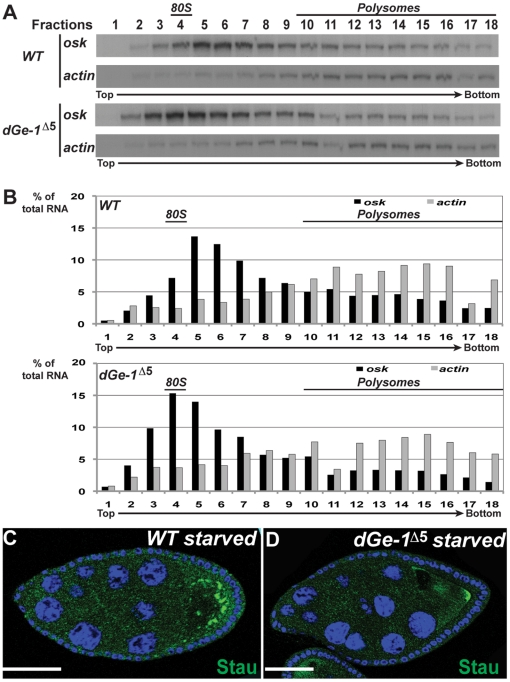

dGe-1 protein is required for P body formation (Figure 2E–J) and is associated with osk RNPs (Figure 4). To determine if dGe-1 might be required for osk RNP assembly, we examined the distribution on sucrose gradients of osk mRNA in cytoplasmic extracts of wt and dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. In wt extracts osk mRNA is broadly distributed and enriched in fractions 5 to 7 (Figure 5A–B). In comparison, translationally active actin mRNA (FlyBase: CG4027) displays a typical polysome profile, with much of the mRNA enriched in the polysomal fractions (Figure 5A–B, fractions 10 to 18). While in dGe-1Δ5 GLC extracts osk mRNA is also distributed broadly, it is most enriched in fractions 3 to 6 (Figure 5A–B). This shift of osk mRNA to the lighter sucrose gradient fractions in dGe-1Δ5 mutant extracts is significant, as no obvious change in the sedimentation profile of actin mRNA was observed. Hence, in the dGe-1Δ5 mutant background the size of osk RNPs is selectively affected, revealing a role of dGe-1 in their assembly or stability. Consistent with this, large osk granules (represented by Stau) induced by nutritional restriction fail to form in dGe-1Δ5 GLC (Figure 5C–D). In the future, it could be of interest to assess the size of osk RNPs in wt and dGe-1 mutant oocytes, for instance by observing their ultrastructure using electron microscopy.

Figure 5. dGe-1 is required for assembly of osk RNPs.

(A) Drosophila wt (upper panel) or dGe-1Δ5 GLC (lower panel) ovarian extracts treated with cycloheximide and analyzed by centrifugation in a 10–45% sucrose density gradient. osk and actin mRNAs in the gradient fractions were detected by RNase protection assay. Absorption at 260 nm was measured to situate the monoribosome peak (80S) and polysomes. (B) Quantification of the RNase protection assays presented in (A). The relative levels of osk and actin mRNAs present in each fraction are indicated as a % of the total levels of both mRNAs present in wt (upper panel) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (lower panel) ovarian extracts. (C–D) Distribution of Stau protein in starved wt (C) or dGe-1Δ5 GLC (D) ovaries. In nutritionally restricted wt oocytes, Stau (green) is present in large particles, which fail to form in starved dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. Bar, 50 µm.

During oogenesis dGe-1 is required for P body formation. This raises the possibility that the mild effect of dGe-1 on osk mRNA localization might be a consequence of P body disruption. It has been shown that upon nutritional restriction, sponge bodies, which are P body-like structures in the Drosophila germline that contain many P body components, are enlarged, and interestingly, osk RNPs are detected within them [31]. Therefore, a direct interaction between osk RNPs and P body-like structures or P bodies themselves may occur, but how this interaction would influence osk mRNA localization remains unclear. In the future, it will be interesting to determine the dynamic relationship between P bodies and osk RNPs, for instance by live-imaging of shared and distinct components and tracking their movement relative to these two RNP structures.

Alternatively, dGe-1 might act directly in an aspect of osk mRNA regulation that is not absolutely essential, such as optimization of the localization process. In support of this hypothesis, our localization and biochemical analyses suggest that, although in the absence of dGe-1 osk RNP assembly may be mildly impaired, under normal laboratory conditions small osk RNPs can form and are sufficiently functional for mRNA localization and posterior patterning to proceed. However, a strong increase in osk localization and posterior patterning defects is observed in the dGe-1 mutant when one wt copy of dDcp1, stau or btz, each of which encodes a component of osk RNPs, is removed. Similarly, depletion of dGe-1, which disrupts P body assembly in Drosophila S2 cells, only mildly affects miRNA-mediated mRNA decay, and the knockdown of dDcp1 or Me31B, both of which are involved in mRNA decapping, has no obvious effect on this process [19]. It is therefore possible that dGe-1 functions to locally concentrate the proteins essential for osk mRNA localization, rendering osk RNP transport more efficient or robust, in particular when some components are limiting. Our study suggests a novel function of dGe-1 in optimization of the process of osk mRNA localization.

Finally, our demonstration of the involvement of dGe-1 in osk mRNA localization in the Drosophila oocyte raises the possibility that P body components and P bodies themselves may contribute to RNA localization, a highly conserved phenomenon, in other eukaryotic cell types and organisms. In addition, the defects in Grk protein expression in dGe-1 mutant ovaries point to a more general role of dGe-1 and presumably of P bodies in mRNA regulation.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks

The following fly strains were used in this study: w1118, YFP-dDcp1 [4], FWS-GFP [21], maternal-α-tub-Gal4:VP16 [32], P[w[+mC] = GSV2] GS5005 (Kyoto Stock Center), oskMS2 [33], y1 w67c23; P{Hsp83-MCP-RFP}12a/TM3, Sb1 (Bloomington Stock Center); UASp-oskBoxB, UASp- λN-GFP (Fan and Ephrussi, unpublished data), stauD3/CyO [30], dDcp1b53/CyO [4], khc27/Cyo [28], btz2/TM3 [29]. GLC were generated as described [20]. For transgenic rescue, a P element-based transgene expressing dGe-1-B cDNA (see below) was crossed into the dGe-1Δ5 mutant background.

Generation of dGe-1 deletion alleles by imprecise excision

The P element bearing the mini-white gene in the fly stock GS5005 was remobilized by imprecise excision. Candidate progeny recognized by their white eye-color were subjected to single fly PCR analysis [34] with three sets of primers against the genomic region of the dGe-1 locus (dGe-1-806F/dGe-1-1302R, dGe-1-806F/dGe-1-1676R and dGe-1-806F/dGe-1-2626R, Table S1). Another two pairs of primers (P5′/dGe-1-2626R and P3′/dGe-1-806F, Table S1) were used to check for the presence of the P element. Finally, the extent of the deleted region in the dGe-1 mutants was determined by sequencing. Genomic analysis of one of these, dGe-1Δ5, revealed a 681 bp-long deletion covering most of the dGe-1 5′ UTR, the putative dGe-1 promoter and a small part of 3′UTR of the upstream gene, CG6192, and a 30 bp insertion of unknown origin in this region (Figure 1A and unpublished data).

Generation of transgenic flies

A full-length dGe-1-B cDNA was generated by PCR using the dGe-1-cDNA-F/dGe-1-cDNA-R primer pair (Table S1) and EST clone LD32717 as a template. The NotI-XbaI PCR fragment was ligated to a NotI-XbaI digested pCasper4-tub vector (gift of S. Cohen). The resulting transgene was used for generation of dGe-1 rescued transgenic flies, which thus express the dGe-1-B cDNA under control of the tub promoter.

To obtain UASp:HA-dGe-1 transgenic flies, the dGe-1 coding region was amplified by PCR using the EST clone LD32717 as a template and the primer set, dGe-1-gateway-F and dGe-1-gateway-R (Table S1). The amplified fragment was cloned into the UASp-based destination vector pPFHW (The Drosophila Gateway Vector Collection), using Gateway Technology (Invitrogen). Cloning into pPFHW results in addition of 3 Flag and 3 HA tags at the N-terminus of the insert.

Antibody generation and western blotting

Rabbit polyclonal anti-dGe-1 antibodies were raised against a C-terminal dGe-1 peptide (amino acids 1220–1354) as described [6].

The following primary antibodies were used for Western Blot analysis: rabbit anti-dGe-1 (1∶500), rat anti-dGe-1 (1∶1,000, gift of E. Izaurralde), rat anti-Cup (1∶500) and mouse anti-Me31B (1∶1,000) (gifts of A. Nakamura), rabbit anti-Khc (1∶50,000, Cytoskeleton), rabbit anti-GFP (1∶50,000, Torrey Pines), rabbit anti-Exu (1∶20,000, gift of P. Macdonald), mouse anti-Tub (1∶10,000, DM1A, Sigma), mouse anti-HA (1∶1,000, HA.11, Convance), rat anti-Grk (1∶2,000, gift of T. Schupbach) and rabbit anti-Osk (1∶2,000).

Ovary and 0–2 h embryo extracts were prepared as described [28], [35].

Immunoprecipitation

Dissected ovaries were homogenized in DXB-150 buffer, and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C [23]. The supernatant was incubated with appropriate antibodies. For immunoprecipitation of GFP- or YFP-tagged proteins, 7 µl of rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Torrey Pines) was used. For immunoprecipitation of endogeneous dGe-1 protein, 10 µl of rabbit anti-dGe-1 antibody were coupled to 25 µl (50% slurry) protein A sepharose beads (GE healthcare) at 4°C overnight on a head-over-tail rotor; the antibody-coupled beads were either incubated or not with dGe-1 peptide (also used to generate dGe-1 antibodies) [6] for 1 h at 4°C; extract was then added and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. To limit unspecific retention on the beads, the matrix was preincubated in 500 µl of blocking buffer (20 mM Hepes-KOH pH 6.95, 550 mM NaCl, 0.1 µg/µl glycogen, 0.1 µg/µl tRNA, 1 µg/µl BSA, 0.1% NP-40) for 16 h at 4°C and resuspended in DXB-150 buffer.

After immunoprecipitation, the beads were washed 6 times for 10 min with 500 µl DXB-150 buffer. For Western blot analysis, the bound proteins were boiled in 2× SDS sample buffer for 10 min at 95°C. For RT-PCR analysis, bound RNAs were extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen), and dissolved in 15 µl H2O.

For the RNAse A sensitivity assay, RNAse A was added to ovarian extracts at a concentration of 0.33 µg/µl prior to immunoprecipitation.

RT-PCR

Total ovarian RNA was extracted and cDNA synthesis was performed as previously described [36]. dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B transcripts were amplified (25 PCR cycles) using the dGe-1-1166F/dGe-1-1420R primer set (Table S1). For evaluation of the relative amounts of dGe-1 transcripts, three sets of primers, dGe-1coding-502F/dGe-1coding-899R, dGe-1coding-2037F/dGe-1coding-2352R and dGe-1coding-3070F/dGe-1coding-3345R, were used (Table S1). As a control, rp49 was detected using rp49F/rp49R primers (Table S1).

For evaluation of mRNA amounts in dGe-1 immunoprecipitates, 5 µl RNA were used for cDNA synthesis using the Superscript III First strand System (Invitrogen), following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, 3 µl of cDNA were used in a 10 µl standard PCR reaction using specific primers for osk, grk, rp49, tub and bcd (Table S1).

Immunostaining and FISH

Ovaries were dissected in cold PBS and processed for immunostaining essentially as previously described [37], using the following antibodies: rat anti-Stau (1∶2,000) [38], rabbit anti-Me31B (1∶4,000), rabbit anti-Tral (1∶1,500), and mouse monoclonal anti-Cup (1∶1,000) (gifts of A. Nakamura), rat anti-dGe-1 (1∶1,000, gift of E. Izaurralde), purified rabbit anti-dGe-1 (1∶100), mouse monoclonal anti-Grk 1D12 (1∶200, DHSB), and mouse monoclonal anti-HA (1∶1,000, HA11, Convance). FISH coupled with immunodetection was performed using a rabbit anti-Osk antibody (1∶3,000) and a digoxigenin-labeled osk antisense probe (at a final concentration of 0.5 ng/µl).

Confocal pictures were taken using an oil-immersion 40× objective on a Leica SP2 confocal microscope and visualized using Leica Confocal Software.

Cuticle preparation

Cuticle preparation was performed as described [39].

Ovary extract preparation for sucrose gradient and RNA analysis

Ovaries were dissected in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, washed twice in 1 ml of SB buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mM DTT, 50 U/ml RNAse inhibitor, 5 mg/ml Heparin, protease inhibitors), resuspended in 200 µl of SB buffer, and homogenized. The extract was centrifuged at 16,110 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant (180 µl) was collected, supplemented with 2 µl Tris-HCl 1M pH 7.5, 2 µl of SB1 buffer 10× (500 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 2.5 M KCl, 25 mM MgCl2), 12.6 µl of H2O and 5.4 µl of cycloheximide 0.1 M and incubated for 30 min at 30°C before sucrose gradient centrifugation.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation and RNA analysis

Typically, 200 µl of extract was layered on a 5.2 ml linear 10–45% sucrose gradients in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 250 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2 and spun in a Beckman SW60 Ti rotor at 50,000 rpm for 40 min at 4°C. 18 fractions were collected from top to bottom, using a Biocomp fractionator. The last fractions were omitted from analysis. RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen) and RNA levels determined by RNase protection assay (Ambion, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The samples were then subjected to electrophoresis on a 5% polyacrylamide/8M urea gel for 2 h at 90W. Data were visualized using Fuji phosphorimager FLA 2100 and quantified using MultiGauge software.

Supporting Information

dGe-1 transcripts are expressed in the Drosophila germline and dramatically reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. (A) RT-PCR amplification of dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B mRNAs from a wt ovarian extract using a pair of primers flanking the alternatively spliced intron of dGe-1. The dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B amplified PCR fragments are of 171 and 254 bp, respectively. (B) The amount of dGe-1 mRNA is severely reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. RT-PCR amplification of dGe-1 transcripts from wt and dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovarian extracts using three pairs of primers targeting different regions of the dGe-1 transcripts (blue, red, and green primers, see Figure 1A). rp49 serves as a loading control.

(TIF)

dGe-1 affects Grk protein expression. (A) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous dGe-1 from wt ovary extract using rabbit anti-dGe1 antibodies either pre-incubated or not with the dGe-1 peptide used for generation of the dGe-1 antibodies in this study. Rabbit IgG antibody serves as a non-specific immunoprecipitation control. Total RNA extracted from the bound fractions was subjected to semi-quantitative RT-PCR (25 cycles). osk, grk, bcd, rp49 and tub RNAs were analyzed. (B–C) Distribution of bcd mRNA in wt (B) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (C) oocytes (in red). DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (D,F) Distribution of grk mRNA in wt (D) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (F) oocytes, detected by FISH (in red). DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (E,G) Distribution of Grk protein (green) in wt (E) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (G) oocytes. DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (H) Western blot analysis of ovary and embryo extracts from wt (first lane), dGe-1Δ5 GLC (second lane), dGe-1 R (third lane) females probed with rat anti-Grk and mouse anti-Tub antibodies. The band around 50 kDa specific to Grk protein is indicated. Tub serves as a loading control. Bar, 50 µm.

(TIF)

dGe-1 cooperates with stau and dDcp1 in osk mRNA localization at S9. (A) Quantification (%) of the different osk mRNA localization phenotypes in S9 egg-chambers of different genetic backgrounds. Normal and abnormal osk mRNA localization are represented by dark and grey bars, respectively. n represents the number of embryos analyzed. (B–D) Distribution of osk mRNA in wt (B), dGe-1Δ5 GLC (C) and dGe-1 R (D) oocytes (in red). DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (E) Western blot analysis of ovarian extracts from wt (first lane) or dGe-1Δ5 GLC (second lane) females probed with rabbit anti-Osk and mouse anti-Tub antibodies. Tub serves as a loading control. Bar, 25 µm.

(TIF)

List of primers used for cloning and RT-PCR analysis.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Tze-Bin Chou, Daniel St Johnston, Eliza Izaurralde, Akira Nakamura, Trudi Schupbach, the Kyoto Stock Center, the Bloomington Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa) for fly stocks and reagents. We are grateful to the EMBL Protein Expression and Purification Core Facility and Laboratory Animal Resources for producing the dGe-1 peptide and antibodies. We thank Sandra Müller for embryo injections and Anna Cyrklaff for help with fly dissection. We are particularly grateful to Imre Gaspar and other members of the Ephrussi lab for discussions during the course of this work.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The totality of the work in this manuscript was funded by the EMBL. Shih-Jung Fan was also fully funded by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (for information about the EMBL, please see http://www.embl.de/aboutus/index.html). Virginie Marchand was supported by a fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale and by the European Molecular Biology Laboratory. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ephrussi A, Lehmann R. Induction of germ cell formation by oskar. Nature. 1992;358:387–392. doi: 10.1038/358387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehmann R, Nusslein-Volhard C. Abdominal segmentation, pole cell formation, and embryonic polarity require the localized activity of oskar, a maternal gene in Drosophila. Cell. 1986;47:141–152. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.St Johnston D. Moving messages: the intracellular localization of mRNAs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:363–375. doi: 10.1038/nrm1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin MD, Fan SJ, Hsu WS, Chou TB. Drosophila decapping protein 1, dDcp1, is a component of the oskar mRNP complex and directs its posterior localization in the oocyte. Dev Cell. 2006;10:601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura A, Amikura R, Hanyu K, Kobayashi S. Me31B silences translation of oocyte-localizing RNAs through the formation of cytoplasmic RNP complex during Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2001;128:3233–3242. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.17.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eulalio A, Behm-Ansmant I, Schweizer D, Izaurralde E. P-body formation is a consequence, not the cause, of RNA-mediated gene silencing. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3970–3981. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00128-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker R, Sheth U. P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:635–646. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eulalio A, Behm-Ansmant I, Izaurralde E. P bodies: at the crossroads of post-transcriptional pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R. Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2005;310:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1115791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Stress-induced reversal of microRNA repression and mRNA P-body localization in human cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:513–521. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decker CJ, Teixeira D, Parker R. Edc3p and a glutamine/asparagine-rich domain of Lsm4p function in processing body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:437–449. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reijns MA, Alexander RD, Spiller MP, Beggs JD. A role for Q/N-rich aggregation-prone regions in P-body localization. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2463–2472. doi: 10.1242/jcs.024976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franks TM, Lykke-Andersen J. The control of mRNA decapping and P-body formation. Mol Cell. 2008;32:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tritschler F, Eulalio A, Truffault V, Hartmann MD, Helms S, et al. A divergent Sm fold in EDC3 proteins mediates DCP1 binding and P-body targeting. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8600–8611. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01506-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenger-Gron M, Fillman C, Norrild B, Lykke-Andersen J. Multiple processing body factors and the ARE binding protein TTP activate mRNA decapping. Mol Cell. 2005;20:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Yang JY, Niu QW, Chua NH. Arabidopsis DCP2, DCP1, and VARICOSE form a decapping complex required for postembryonic development. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3386–3398. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu JH, Yang WH, Gulick T, Bloch KD, Bloch DB. Ge-1 is a central component of the mammalian cytoplasmic mRNA processing body. RNA. 2005;11:1795–1802. doi: 10.1261/rna.2142405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jinek M, Eulalio A, Lingel A, Helms S, Conti E, et al. The C-terminal region of Ge-1 presents conserved structural features required for P-body localization. RNA. 2008;14:1991–1998. doi: 10.1261/rna.1222908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eulalio A, Rehwinkel J, Stricker M, Huntzinger E, Yang SF, et al. Target-specific requirements for enhancers of decapping in miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2558–2570. doi: 10.1101/gad.443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou TB, Perrimon N. The autosomal FLP-DFS technique for generating germline mosaics in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1996;144:1673–1679. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farkas RM, Giansanti MG, Gatti M, Fuller MT. The Drosophila Cog5 homologue is required for cytokinesis, cell elongation, and assembly of specialized Golgi architecture during spermatogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:190–200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferraiuolo MA, Basak S, Dostie J, Murray EL, Schoenberg DR, et al. A role for the eIF4E-binding protein 4E-T in P-body formation and mRNA decay. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:913–924. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura A, Sato K, Hanyu-Nakamura K. Drosophila cup is an eIF4E binding protein that associates with Bruno and regulates oskar mRNA translation in oogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;6:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth S, Neuman-Silberberg FS, Barcelo G, Schupbach T. cornichon and the EGF receptor signaling process are necessary for both anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral pattern formation in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:967–978. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St Johnston D, Driever W, Berleth T, Richstein S, Nusslein-Volhard C. Multiple steps in the localization of bicoid RNA to the anterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 1989;107(Suppl):13–19. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.Supplement.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim-Ha J, Smith JL, Macdonald PM. oskar mRNA is localized to the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Cell. 1991;66:23–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90136-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ephrussi A, Dickinson LK, Lehmann R. Oskar organizes the germ plasm and directs localization of the posterior determinant nanos. Cell. 1991;66:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90137-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brendza RP, Serbus LR, Duffy JB, Saxton WM. A function for kinesin I in the posterior transport of oskar mRNA and Staufen protein. Science. 2000;289:2120–2122. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Eeden FJ, Palacios IM, Petronczki M, Weston MJ, St Johnston D. Barentsz is essential for the posterior localization of oskar mRNA and colocalizes with it to the posterior pole. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:511–523. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200105056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St Johnston D, Beuchle D, Nusslein-Volhard C. Staufen, a gene required to localize maternal RNAs in the Drosophila egg. Cell. 1991;66:51–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90138-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snee MJ, Macdonald PM. Dynamic organization and plasticity of sponge bodies. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:918–930. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hacker U, Perrimon N. DRhoGEF2 encodes a member of the Dbl family of oncogenes and controls cell shape changes during gastrulation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1998;12:274–284. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimyanin VL, Belaya K, Pecreaux J, Gilchrist MJ, Clark A, et al. In vivo imaging of oskar mRNA transport reveals the mechanism of posterior localization. Cell. 2008;134:843–853. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gloor GB, Preston CR, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Nassif NA, Phillis RW, et al. Type I repressors of P element mobility. Genetics. 1993;135:81–95. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markussen FH, Michon AM, Breitwieser W, Ephrussi A. Translational control of oskar generates short OSK, the isoform that induces pole plasma assembly. Development. 1995;121:3723–3732. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Besse F, Lopez de Quinto S, Marchand V, Trucco A, Ephrussi A. Drosophila PTB promotes formation of high-order RNP particles and represses oskar translation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:195–207. doi: 10.1101/gad.505709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vanzo NF, Ephrussi A. Oskar anchoring restricts pole plasm formation to the posterior of the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 2002;129:3705–3714. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.15.3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krauss J, Lopez de Quinto S, Nusslein-Volhard C, Ephrussi A. Myosin-V regulates oskar mRNA localization in the Drosophila oocyte. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieschaus E, Nusslein-Volhard C, Kluding H. Kruppel, a gene whose activity is required early in the zygotic genome for normal embryonic segmentation. Dev Biol. 1984;104:172–186. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

dGe-1 transcripts are expressed in the Drosophila germline and dramatically reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. (A) RT-PCR amplification of dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B mRNAs from a wt ovarian extract using a pair of primers flanking the alternatively spliced intron of dGe-1. The dGe-1-A and dGe-1-B amplified PCR fragments are of 171 and 254 bp, respectively. (B) The amount of dGe-1 mRNA is severely reduced in dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovaries. RT-PCR amplification of dGe-1 transcripts from wt and dGe-1Δ5 GLC ovarian extracts using three pairs of primers targeting different regions of the dGe-1 transcripts (blue, red, and green primers, see Figure 1A). rp49 serves as a loading control.

(TIF)

dGe-1 affects Grk protein expression. (A) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous dGe-1 from wt ovary extract using rabbit anti-dGe1 antibodies either pre-incubated or not with the dGe-1 peptide used for generation of the dGe-1 antibodies in this study. Rabbit IgG antibody serves as a non-specific immunoprecipitation control. Total RNA extracted from the bound fractions was subjected to semi-quantitative RT-PCR (25 cycles). osk, grk, bcd, rp49 and tub RNAs were analyzed. (B–C) Distribution of bcd mRNA in wt (B) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (C) oocytes (in red). DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (D,F) Distribution of grk mRNA in wt (D) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (F) oocytes, detected by FISH (in red). DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (E,G) Distribution of Grk protein (green) in wt (E) and dGe-1Δ5 GLC (G) oocytes. DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (H) Western blot analysis of ovary and embryo extracts from wt (first lane), dGe-1Δ5 GLC (second lane), dGe-1 R (third lane) females probed with rat anti-Grk and mouse anti-Tub antibodies. The band around 50 kDa specific to Grk protein is indicated. Tub serves as a loading control. Bar, 50 µm.

(TIF)

dGe-1 cooperates with stau and dDcp1 in osk mRNA localization at S9. (A) Quantification (%) of the different osk mRNA localization phenotypes in S9 egg-chambers of different genetic backgrounds. Normal and abnormal osk mRNA localization are represented by dark and grey bars, respectively. n represents the number of embryos analyzed. (B–D) Distribution of osk mRNA in wt (B), dGe-1Δ5 GLC (C) and dGe-1 R (D) oocytes (in red). DNA stained with DAPI (blue). (E) Western blot analysis of ovarian extracts from wt (first lane) or dGe-1Δ5 GLC (second lane) females probed with rabbit anti-Osk and mouse anti-Tub antibodies. Tub serves as a loading control. Bar, 25 µm.

(TIF)

List of primers used for cloning and RT-PCR analysis.

(DOC)