Abstract

Altered serine protease activity is associated with skin disorders in humans and in mice. The serine protease channel-activating protease-1 (CAP1; also termed protease serine S1 family member 8 (Prss8)) is important for epidermal homeostasis and is thus indispensable for postnatal survival in mice, but its roles and effectors in skin pathology are poorly defined. In this paper, we report that transgenic expression in mouse skin of either CAP1/Prss8 (K14-CAP1/Prss8) or protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2; Grhl3PAR2/+), one candidate downstream target, causes epidermal hyperplasia, ichthyosis and itching. K14-CAP1/Prss8 ectopic expression impairs epidermal barrier function and causes skin inflammation characterized by an increase in thymic stromal lymphopoietin levels and immune cell infiltrations. Strikingly, both gross and functional K14-CAP1/Prss8-induced phenotypes are completely negated when superimposed on a PAR2-null background, establishing PAR2 as a pivotal mediator of pathogenesis. Our data provide genetic evidence for PAR2 as a downstream effector of CAP1/Prss8 in a signalling cascade that may provide novel therapeutic targets for ichthyoses, pruritus and inflammatory skin diseases.

The activity of serine proteases, including CAP1/Prss8, is altered in some human skin disorders; however, the downstream effectors of these proteins are relatively unknown. Here, using animal models, the authors show that protease-activated receptor-2 is a critical component of the CAP1/Prss8 signalling cascade.

The activity of serine proteases, including CAP1/Prss8, is altered in some human skin disorders; however, the downstream effectors of these proteins are relatively unknown. Here, using animal models, the authors show that protease-activated receptor-2 is a critical component of the CAP1/Prss8 signalling cascade.

Human skin disorders such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis and ichthyoses range in severity from mild to life threatening, and share characteristics of inflammation, defects in epidermal barrier function, skin desquamation and pruritus in affected patients (reviewed in refs 1 and 2). Our understanding of their molecular and genetic origins is improving3,4,5, with serine proteases emerging among possible disease-causing culprits. Gene-targeting experiments in mice revealed a critical role for membrane-bound serine proteases, particularly those of the S1 or trypsin-like family6 in postnatal epidermal barrier function7,8,9. It also emerged that inadequate regulation of serine protease activity in the skin of both mice7,8,10 and humans4 could disrupt skin homeostasis. However, which serine proteases need to be tightly regulated to prevent disease and how they mediate skin pathology when deregulated are still incompletely defined.

Channel-activating protease-1 (CAP1; also termed protease serine S1 family member-8 (Prss8)), the mouse homologue of human prostasin, is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored serine protease11. CAP1/Prss8 is expressed at high levels in the prostate gland12, and is also found in a variety of other organs such as skin, colon, lung and kidney13. We have previously shown that CAP1/Prss8 is predominantly expressed in granular and spinous layers of the epidermis where it is crucial for epidermal barrier function and thereby indispensable for postnatal survival8. Membrane-bound serine proteases exhibit pleiotropic functions not only by cleaving growth factors, zymogen proteases and extracellular matrix proteins14 but also by inducing cell signalling through members of the proteinase-activated receptor (PAR) family of G-protein-coupled receptors15. It was recently demonstrated that CAP1/Prss8 can function upstream in a proteolytic cascade that culminates in PAR2 activation16; yet, genetic evidence that CAP1/Prss8 can evoke PAR2 signalling in vivo is lacking. PAR2 is widely expressed in skin, including keratinocytes, endothelial cells and sensory nerves17,18,19,20, in which it has already been implicated in the regulation of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation21, maintenance of the epidermal barrier22, inflammation17,18 and pruritus20,23. Both CAP1/Prss8 and PAR2 are expressed in the suprabasal granular layers of the epidermis8,17,24, supporting a possible interaction between the two.

In this study, to directly address the potential contribution of deregulated CAP1/Prss8 and PAR2 expression to skin pathology, we manipulated epidermal CAP1/Prss8 and PAR2 expression in transgenic mouse lines (K14-CAP1/Prss8, Grhl3PAR2/+). The two models yielded modestly increased as well as ectopic expression of CAP1/Prss8 or PAR2, and exhibited similar phenotypes characterized by scaly skin, hyperplastic epidermis and scratching behaviour. Having established the ability of protease and signalling receptor to independently cause skin pathology, we addressed whether they also cooperated to drive pathogenesis as might be suggested by signalling studies16. We indeed observed that the K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgene completely lost its capacity to induce skin pathology in the absence of PAR2, placing PAR2 as a pivotal mediator downstream of CAP1/Prss8 in this model. We thus demonstrate that altered CAP1/Prss8 expression triggers PAR2-dependent inflammation, ichthyosis and itching, supporting the requirement for tight control of protease activity in skin homeostasis, and implicating PAR2 as a potential mediator of pathologies linked to loss of serine protease regulation in skin.

Results

Generation and characterization of K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice

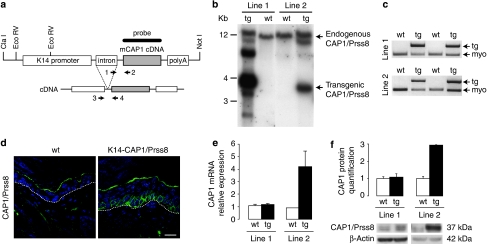

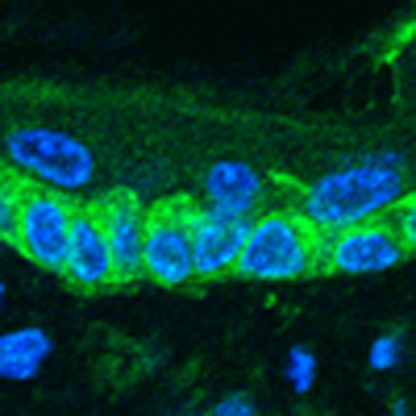

To study the biological consequence of deregulated CAP1/Prss8 expression in skin, we generated transgenic mice expressing the full-length mouse CAP1/Prss8 coding sequence13 under the control of the human keratin-14 promoter25 (Fig. 1a). This promoter targets gene expression to keratinocytes of the basal layer of the epidermis and the outer root sheath of hair follicles25. Pronuclear injections of the K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgene construct yielded five founders, two of which were fertile and transmitted the transgene to produce two independent stable transgenic lines (termed lines 1 and 2; Fig. 1b,c). The transgene was transmitted according to Mendelian inheritance in both lines (line 1: 54% tg, n=95; line 2: 54% tg, n=72), suggesting that the level of CAP1/Prss8 expression obtained did not interfere with embryonic development. For line 1, only male mice (all of them) were transgenic, indicating integration of the transgene into the Y chromosome. Both transgenic lines expressed the transgene in skin as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. S1a). Analysis of total (transgene-driven plus endogenous) expression of CAP1/Prss8 demonstrated a 1.1- and 4.7-fold increase in transcript levels and a 1.1- and 2.9-fold increase in protein levels in lines 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 1e,f), indicating higher CAP1/Prss8 expression levels in line 2.

Figure 1. Generation of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice.

(a) Scheme of the K14-CAP1/Prss8 construct containing the mouse CAP1/Prss8 coding sequence (cDNA, g.i. 19111159), the human K14 promoter, the rabbit β-globin intron and the human growth hormone polyadenylation signal (polyA). Restriction sites used for isolation of the transgene (ClaI, NotI) and for Southern blot analysis (EcoRV) are indicated. For transgene-specific genotyping, primers 1 and 2, and for reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR, primers 3 and 4 (arrows), were used. (b) Detection of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice (line 1 and line 2) following Southern blot analysis (wild type, wt, 12 kb; transgenic, tg, 3.6 kb). (c) PCR genotyping using transgene-specific primers 1 and 2 (see a) and myogenin-specific primers (myo; endogenous control). (d) Immunofluorescence (green) shows transgenic CAP1/Prss8 expression in the basal layer of the epidermis in K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice. The white dotted line represents the basal membrane. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The white bar indicates 20 μm; (b–d) n≥4 mice/genotype. (e) CAP1/Prss8 gene expression in the skin was determined by quantitative RT–PCR analysis and normalized to β-actin. Line 1: n=3 animals/genotype. Line 2: wt, n=2 (data: 0.92 and 0.87) and tg, n=4 animals analysed. (f) CAP1/Prss8 protein expression was quantified by western blotting and loading was controlled by β-actin. Line 1: n=3 animals per genotype. Line 2: n=4 animals per genotype. All data are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Epidermal defects and death in K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice

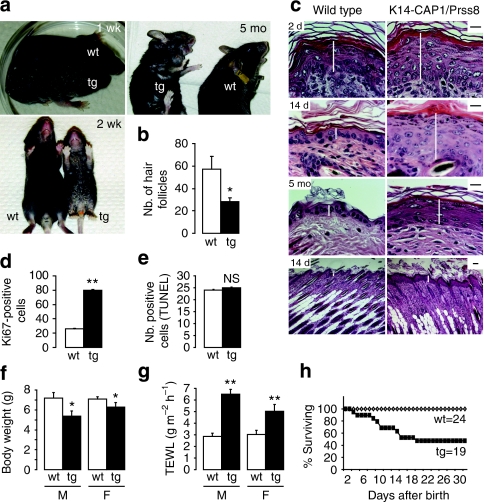

K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice were easily discernible from their control littermates just a few days after birth by their scaly skin (ichthyosis), which progressed with age and was evident most prominently in the ventral-abdominal region and the tail (line 2, Fig. 2a, line 1; Supplementary Fig. S1b). Both transgenic lines manifested ichthyosis with 100% penetrance, as well as abnormal hair growth (hypotrichosis) relative to littermate controls (Fig. 2b). No histopathological abnormalities were observed in other organs, such as thymus, tongue, oesophagus, heart, liver, lung and spleen (Supplementary Fig. S2). Histological analysis revealed epidermal hyperplasia (acanthosis) in transgenic mice from as early as 2 days of age (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. S1c) associated with enhanced proliferation of keratinocytes, as evidenced by a threefold increase in the number of Ki67-positive cells in the stratum basale (Fig. 2d), without an accompanying change in the number of apoptotic cells in the epidermis (Fig. 2e). In addition to epidermal hyperplasia, the dermis of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice was more cellular with a notable increase in the number of haematoxylin-stained nuclei (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2. Phenotype of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice.

(a) Macroscopic appearance of transgenic mice and littermate controls at 1 week (1 wk), 2 weeks (2 wk) and 5 months (5 mo) of age. (b) Quantification of the number (Nb.) of hair follicles in transgenic versus control skin. n=3 mice per genotype, *P<0.05. (c) Haematoxylin and eosin analyses of 2-day (2 d)-, 2-week (14 d)- and 5-month (5 mo)-old K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice compared with wild-type littermates. White bars indicate the thickness of the epidermis. Scale bars indicate 20 μm. n=3 mice per genotype. (d) Quantification of the number of Ki67-positive cells in the epidermis of 2-week-old animals. (e) Quantification of the number (Nb.) of cells undergoing apoptosis in the epidermis of K14-CAP1/Prss8 versus wild-type littermates (n=3 mice per genotype, NS: not significant). (f) Body weight measurements of 2-week-old male (M) and female (F) transgenic mice and littermate controls, *P<0.05. (g) Transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurements of male and female transgenic mice. n≥4 animals per group, **P<0.01. (h) Survival curves of K14-CAP1/Prss8 versus wild-type littermates. All data are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Despite differences in CAP1/Prss8 expression levels, mice from both transgenic lines also manifested a significant reduction in body weight (Fig. 2f; Supplementary Fig. S1d) accompanied by an up to twofold increase in transepidermal water loss (TEWL) evident in 2-week-old animals (Fig. 2g; Supplementary Fig. S1e) and maintained in adults (TEWL: 3.31 g m−2 h−1 in wild type (wt) versus 6.90 g m−2 h−1 in tg, P<0.05, n=6 and 7, respectively, in line 1. 2.87 g m−2 h−1 in wt versus 6.02 g m−2 h−1 in tg, P<0.05, n=6 and 4, respectively, in line 2; Body weight: 37.49 g in wt versus 32.62 g in tg, n=6 and 7, respectively, in line 1 and 37.64 g in wt versus 26.06 g in tg, P<0.001, n=6 and 4, respectively, in line 2) indicative of a defect in the skin barrier function. Many transgenic mice from line 2 died within the first 2 weeks (∼55 versus 10% in line 1, Fig. 2h; Supplementary Fig. S1f), but survival was not further impaired thereafter. Although we did not address it directly, we speculate that death of these animals may be a consequence of severe dehydration.

Altered lipid and protein content in K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice

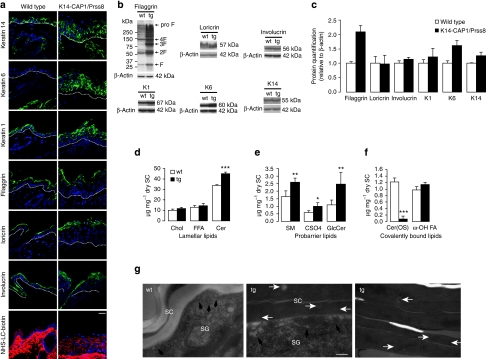

To explore the basis for skin barrier defects observed in K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice, we first looked for alterations in expression of keratinocyte differentiation markers by immunohistochemistry and western blot. Expression of keratin-1, loricrin, filaggrin and involucrin appeared to be more widespread within the epidermis of K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice, but there was no obvious change in distribution within the differentiated layers (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. S1g), and expression levels were normal with the exception of filaggrin. Levels of all proteolytically cleaved intermediates of filaggrin were increased (Fig. 3b,c; Supplementary Fig. S1h,i). Moreover, the differentiation marker keratin-14, normally expressed exclusively in the stratum basale and hair follicles, was now detected in all nucleated epidermal cell layers. The expression of keratin-6, normally present only in hair follicles, was also detectable in interfollicular keratinocytes (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Fig. S1g), consistent with epidermal hyperplasia.

Figure 3. Altered protein and lipid composition in K14-CAP1/Prss8 epidermis.

(a) Epidermal differentiation markers (keratin-14, -6, -1, filaggrin, loricrin and involucrin) as present (green) in both wild-type and transgenic mice. Dotted lines indicate basal membrane. Below: tight junction permeability assay using NHS-LC-biotin (red). Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar represents 20 μm; n=3 mice per group. (b) Western blot analyses demonstrate the expression of filaggrin, loricrin, involucrin, keratin-1 (K1), keratin-6 (K6) and keratin-14 (K14) in skin of transgenic and control mice. Loading is controlled by β-actin and proteins are quantified in (c), n≥4 animals per group. (d) Analysis of unbound stratum corneum lipids by thin layer chromatography in transgenic versus littermate controls. Cholesterol (Chol), ceramide (Cer), free fatty acids (FFA). (e) Analysis of probarrier lipids sphingomyelin (SM), cholesterol sulphate (CSO4) and glucosylceramide (GlcCer). (f) Covalently bound lipids: In K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice, ceramide (OS) levels (Cer(OS)) were reduced to 6.3% of controls. (Chl: cholesterol, FFA: free fatty acids, ω-OH FA: ω-hydroxy fatty acids), n≥3 mice per group; (c–f) All data are presented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (g) Electron microscopy of skin of K14-CAP1/Prss8 2-week-old transgenic (n=4) and wild-type littermates (n=3) depicting interface between stratum granulosum (SG) and stratum corneum (SC; left, middle panel). Lamellar bodies are shown in the SG (black) and SC (white arrows). Right panel: intermediate portion of hyperkeratotic scales in transgenic mice. Scale bar represents 200 nm.

To test the integrity of intercellular tight junctions in the granular layer of the epidermis, we injected NHS-LC-biotin (600 Da) into the dermis and subsequently visualized its diffusion on sections stained with fluorescently conjugated streptavidin. NHS-LC biotin diffused freely between cells up to the second-last nucleated layer of the epidermis with no discernable difference between transgenic mice and littermate controls (Fig. 3a). Thus, the epithelial barrier within the granular layer appeared fully functional at least for molecules ≥600 Da.

The extracellular lipid barrier in the stratum corneum consists mainly of ceramides, free fatty acids and cholesterol present in a unique and stoichiometric composition. The ceramides are preferentially composed of probarrier lipids glucosylceramide, sphingomyelin and cholesterol sulphate26. Ceramide levels were significantly higher in transgenic mice (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. S1j), and more ceramide forms with longer fatty acids were present as seen by ceramide fractionation and densitometric quantification (Cer(C-26)-NS, Cer(C26-AS), Cer(C26-NH) and Cer(EOS); Supplementary Table S1), as well as more ceramide precursors glucosylceramide and sphingomyelin. Cholesterol sulphate levels were nearly 1.8-fold higher than that of controls (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Fig. S1k). Covalently bound lipids, which are also important for skin barrier function27, were then separated into ω-hydroxylated fatty acid and Cer(OS), showing that Cer(OS) levels were only 6.3% of that of control mice in line 2 (Fig. 3f) and 14% of that of control mice in line 1 (Supplementary Fig. S1l).

The hydrophobic water-protective barrier of the skin consisting of lipids originates from lamellar bodies secreted by keratinocytes of the granular layer28. Electron microscopy analyses revealed that secretion of lamellar bodies is diminished in the transgenic epidermis and that numerous lamellar body-like inclusions are present in transgenic corneocytes (Fig. 3g). The stratum granulosum–stratum corneum interface appeared to be widened in transgenic mice, containing less vesicular lamellar bodies and more electron-dense amorphous material. The process of corneodesmosome degradation and stratum corneum desquamation was delayed in the transgenic epidermis relative to control epidermis (Fig. 3g). Thus, defective epidermal barrier function in K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice is likely to originate from altered epidermal protein-lipid composition.

Itching and inflamed skin in K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice

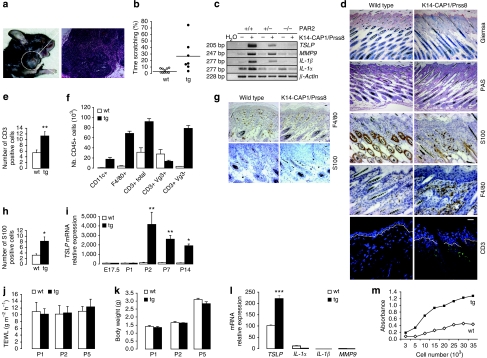

Transgenic animals surviving till adulthood frequently exhibited skin lesions (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. S1m) possibly caused or aggravated by increased scratching behaviour (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Fig. S1n), which was evident after weaning and persistent throughout life. Lesions were sometimes accompanied by inflammation and swelling of regional lymph nodes, which were found to be enriched in plasma cells (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Fig. S1m).

Figure 4. K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice exhibit itching and severe skin inflammation.

(a) Skin injuries with open wounds and lymph node inflammation (haematoxylin and eosin staining, bar represents 20 μm) in a representative 7-month-old transgenic mouse. (b) Dot plot indicating the duration of the scratching behaviour expressed in percentage. Each dot represents a single event per animal. Bars indicate the average of the time spent scratching, P<0.01. (c) Semiquantitative RT–PCR analysis of TSLP, MMP9, IL-1β and IL-1α (30 cycles) in transgenic versus wild-type skin. The reaction is controlled by detection of β-actin (25 cycles). Water was used as negative control. Data are representative of n=3 mice per genotype. (d) Giemsa, periodic acid-Schiff staining and S100, F4/80 and CD3 labelling in skin of 2-week-old wild-type and K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice. Pictures are representative of n=3 animals per genotype. Bars represent 20 μm. (e) Quantification of the number of CD3-positive cells in transgenic versus wild-type skin. n=3 mice per genotype, *P<0.01. (f) FACS analysis of dendritic cells (CD11c+), macrophages (F4/80+) and Tγ cells (CD3+; CD3+/Vg3+; and CD3+/Vg3-) in skin of 6-day-old pups (n=3 mice per genotype). (g) F4/80 and S100-positive cells in skin of 2-day-old transgenic and littermate controls. Bar represents 20 μm; pictures are representative of n=3 mice per genotype. (h) Quantification of the number of S100-positive cells in 2-day-old transgenic and littermate animals. n=3 mice per genotype, *P<0.05. (i) TSLP quantitative RT–PCR analyses of wild-type and transgenic skin in 2-day-old pups (n≥3 mice per group, *P<0.05, **P<0.01). (j) TEWL and body weight (k) measurements at P1, P2 and P5 (n≥4 mice per group). (l) Quantitative RT–PCR examination of TSLP, IL1α, IL1β and MMP9 in transgenic primary keratinocytes, ***P<0.001. (m) Quantification of cell growth assessed in primary keratinocytes derived from 2-day-old transgenic and control littermates. (l, m) The data are representative of three independent experiments. All data are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Epidermal thickening and increased dermal cellularity (Fig. 2c) are often observed in mice with skin inflammation29. To address the characteristics and the origin of the inflammatory phenotype and how it correlated with epidermal hyperplasia, barrier dysfunction and itching, we explored the expression of cytokines and procytokines in the skin of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice. Interleukin-1α (IL-1α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and the extracellular matrix remodelling enzyme matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) were upregulated relative to littermate controls (Fig. 4c). Histological staining of 2-week-old transgenic skin showed no evidence of parasites, blood cells (Giemsa staining), lymphocytes or mucopolysaccarides, and hence no fungal infections (periodic acid-Schiff). However, S100, a common antigen for dendritic cells and macrophages, and the macrophage-specific antigen F4/80 (ref. 30) were both more abundant in the skin of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice than in that of littermate controls. Consistent with the increase in antigen-presenting cells, CD3-positive T cells were also more abundant in the skin of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice (Fig. 4d,e). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses of 6-day-old pups revealed an increase in the number of CD11c- (a marker for dendritic cells31), F4/80- and CD3-positive cells, and showed abnormal presence of CD3-positive/Vg3-negative T cells32 in the K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic skin already at this time (Fig. 4f). Two-day-old K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic pups also had increased numbers of S100-positive cells (Fig. 4g,h), but there was not yet a difference in F4/80 staining at this time (Fig. 4g). This suggests an inflammatory phenotype in the skin of transgenic mice with very early onset, and a potential initiating role for dendritic cells in this process.

As dendritic cell-mediated skin inflammation has been linked to TSLP production by keratinocytes33, we further investigated TSLP expression in the skin by real-time PCR. Although no difference was seen at embryonic day 17.5 (E17.5) or at postnatal day 1 (P1), a dramatic increase in TSLP expression was observed in transgenic skin at P2, P7 and P14 (Fig. 4i). No difference in TEWL or body weight was observed at P1, P2 and P5 (Fig. 4j,k), indicating that the defective barrier function and decrease in body weight might be secondary to epidermal hyperplasia and skin inflammation. Primary keratinocytes derived from transgenic and control littermates at P2 showed increased TSLP expression (Fig. 4l) and proliferation rates (Fig. 4m), suggesting that hyperplasia and inflammation might both originate in the transgenic keratinocytes. Transcripts for proinflammatory mediators IL-1α, IL-1β and MMP9 were barely or not at all detectable in the same cells (Fig. 4l). Thus, chronic skin inflammation, characterized by immune cell infiltration and expression of procytokines and cytokines, occurs early in parallel to epidermal hyperplasia in K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice. Although apparently not causative, barrier dysfunction and itching may later aggravate these phenotypes.

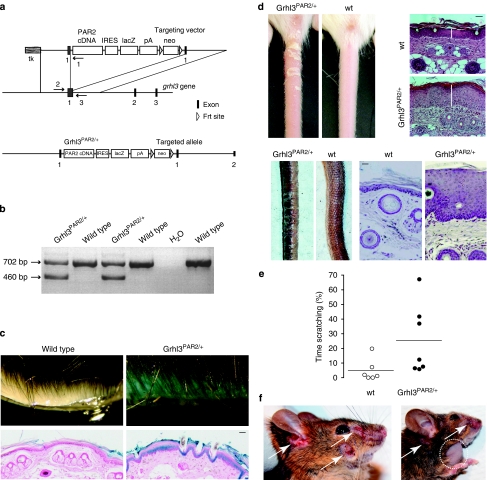

Ichthyosis and itching in Grhl3PAR2/+ mice

To probe the contribution of PAR2 signalling to skin disease, we addressed whether increased expression of PAR2 in mouse skin might induce a pathological transformation similar to what had been observed with altered CAP1/Prss8 activity. We inserted a cassette consisting of the mouse PAR2 coding sequence followed by an internal ribosomal entry site and the lacZ reporter gene at the start codon of the grainyhead-like-3 (Grhl3) gene (Grhl3PAR2/+) by homologous recombination (Fig. 5a,b). The Grhl3 locus drives the expression of PAR2 throughout the epithelial ectoderm from mid-gestation onwards16,34,35. Consistent with simultaneous interruption of the Grhl3 gene, mice with PAR2 inserted in both alleles (Grhl3PAR2/PAR2) died perinatally with spina bifida34. Therefore, Grhl3PAR2/+ mice were used throughout this study for transgenic PAR2 overexpression. Importantly, mice carrying one functional allele of the Grhl3 gene (Grhl3+/−) do not exhibit phenotypic differences compared to wt controls34, and knock-in of the Cre recombinase into the Grhl3 gene locus also affects Grhl3 gene expression, but does not trigger skin pathology16.

Figure 5. Generation and characterization of Grhl3PAR2/+ transgenic mice.

(a) Scheme of the Grhl3PAR2/+ knock-in targeting vector, part of the targeted Grhl3 gene locus and the resulting targeted allele. Exons (black boxes), transgenic sequences (from the left, white boxes: mouse PAR2 coding sequence [PAR2 cDNA], internal ribosome entry site [IRES], lacZ coding sequence [lacZ], poly A signal [pA], neomycin cassette [neo]) and Frt sites (open triangles) are shown. Primers 1, 2 and 3 used for PCR genotyping are represented (arrows). Primers 1 and 2 amplify the mutant Grhl3PAR2 allele, and primers 2 and 3 amplify the endogenous Grhl3 allele. (b) PCR-based genotyping of Grhl3PAR2/+ transgenic mice. Amplified fragments using specific primers reveal the mutant (460 bp) and endogenous (702 bp) Grhl3 alleles. (c) β-Galactosidase staining (light blue) on skin autopsy samples and on skin sections from Grhl3PAR2/+ mice counterstained with neutral red (pink) of the respective genotypes. Bar represents 10 μm. (d) Phenotypic appearance and haematoxylin- and eosin-stained skin of Grhl3PAR2/+ mice versus control littermates at 2 weeks of age (top panel) and in adulthood (lower panel). Scale bars represent 20 μm. (e) Dot plot indicating the percentage of monitoring time spent scratching or grooming. Bars indicate the average of the time spent scratching. Each dot represents a single animal (P<0.05). (f) Skin injuries (white arrows) become evident in adult Grhl3PAR2/+ transgenic mice with occasional swelling of regional lymph nodes (dotted circle). (c, d, f) n≥3 mice per group.

The expression of the Grhl3PAR2/+ allele, as monitored by lacZ staining, was found predominantly in the suprabasal layers of the epidermis (Fig. 5c). Although Grhl3PAR2/+ mice appeared normal at birth, they started to exhibit a scaly skin, mostly evident on the tail, and epidermal hyperplasia from 2 weeks onwards (Fig. 5d). Similar to K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice, Grhl3PAR2/+ animals displayed increased scratching behaviour in adulthood (Fig. 5e) and severe skin lesions associated with occasional lymph node swelling (Fig. 5f). Notably, scratching behaviour was not observed in young mice or in adult mice without lesions, and did not appear to precede lesion formation. The common features in the phenotype of Grhl3PAR2/+ and K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice support a possible role for PAR2 in CAP1/Prss8-induced skin pathology.

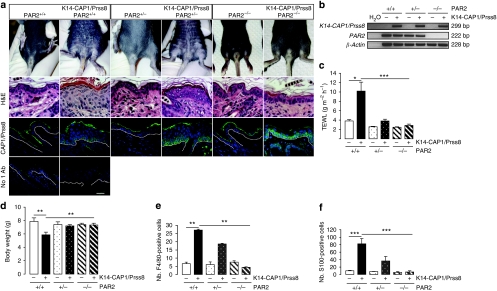

PAR2 deficiency rescues K14-CAP1/Prss8-induced skin defects

To address whether CAP1/Prss8 can trigger PAR2 activation in vivo and to experimentally test whether the similarities between Grhl3PAR2/+ and K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic animals were due to excessive PAR2 activation in both models, we crossed K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice from line 2 with mice constitutively and globally deficient in PAR2 (PAR2−/−) that do not exhibit obvious skin abnormalities36. Mice carrying the K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgene that were either wt (K14-CAP1/Prss8) or heterozygous mutant for PAR2 (K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/−) displayed scaly skin with epidermal hyperplasia (Fig. 6a). In contrast, no scaling, epidermal hyperplasia or premature lethality was observed in K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice that were homozygous mutant for PAR2 (K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/−, Fig. 6a and Table 1). Despite the absence of PAR2, these mice still expressed the K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgene (Fig. 6a,b). The rescue was also evident functionally, as K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− mice exhibited TEWL in the same range as that of wt controls but significantly different from that of K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/+ littermates (Fig. 6c). Moreover, whereas K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice displayed a significantly lower body weight compared with controls, the K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− mice were indistinguishable from littermate controls in this regard (Fig. 6d). Surprisingly, heterozygosity for PAR2 was sufficient to reverse the increased water loss and reduced body weight observed in K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice, despite persistence of ichthyotic and hyperplastic phenotypes (Fig. 6c,d). Moreover, expression levels of inflammatory markers IL-1α, IL-1β, TSLP and MMP9, as well as of macrophage and dendritic cell markers anti-F4/80 and anti-S100, were indistinguishable from control levels in K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− animals (Figs 4c and 6e,f). K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/− mice manifested an intermediate phenotype, suggesting a dose-dependent effect of PAR2. Thus, absence of PAR2 completely rescued hyperplasia, barrier dysfunction, inflammation and ichthyosis caused by altered CAP1/Prss8 expression in the skin, establishing PAR2 as a pivotal mediator of K14-CAP1/Prss8-driven skin pathology in this model.

Figure 6. Ichthyosis and inflammation are absent in K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− mice.

(a) Macroscopic appearance of 2-week-old animals. H&E: haematoxylin and eosin staining of skin. Immunofluorescence (green) shows transgenic CAP1/Prss8 expression at the basal layer in K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/+, K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/− and K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− transgenic mice. Below: negative control (omission of primary antibody, no 1Ab). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue), n≥3 mice per group. Bar represents 20 μm. (b) RT–PCR analysis demonstrates expression of the CAP1/Prss8 transgene in K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/+, K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2+/− and K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− transgenic mice, and absence of PAR2 gene expression in PAR2−/− animals. β-actin was used to control cDNA, and H2O provided negative control. The blot is representative of three animals analysed per group. (c) Transepidermal water loss and body weight analyses (d) in experimental and control animals, n≥8 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. (e) Numbers (nb.) of F4/80- and (f) S100-positive cells evident in the skin of 2-week-old animals; (e, f) n=3 mice per genotype. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. All data are presented as mean±s.e.m.

Table 1. PAR2 deficiency prevents the K14-CAP1/Prss8-induced phenotype in double-transgenic K14-CAP1/Prss8:PAR2−/− mice (line 2).

| Genotype | K14-CAP1/Prss8 | PAR−/− | K14-CAP1/Prss8 | PAR2+/− | K14-CAP1/Prss8 | PAR2+/+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breeding pairs | PAR−/− | PAR+/− | PAR2+/+ | |||

| K14-CAP1/Prss8 PAR2+/−×PAR2+/−, n=135 | 18 | 20 | 34 | 31 | 16 | 16 |

| Observed, % | 13.3 | 14.8 | 25.2 | 23.0 | 11.9 | 11.9 |

| Expected, % | 12.5 | 12.5 | 25 | 25 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| K14-CAP1/Prss8 PAR2+/−×PAR2−/−, n=71 | 12 | 16 | 26 | 17 | − | − |

| Observed, % | 17 | 23 | 37 | 24 | − | − |

| Expected, % | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | − | − |

| CAP1/Prss8 scaly skin phenotype | − | − | + | − | + | − |

| Animals found dead |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

Pups were analysed during the first 3 weeks after birth. Number of mice for the recorded genotypes is indicated.

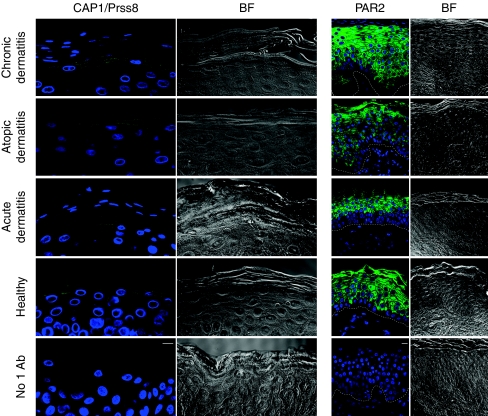

Expression of CAP1/Prss8 and PAR2 in human skin

CAP1/Prss8 immunodetection on skin cross-sections from four healthy controls and from five acute, two atopic and three chronic dermatitis patients showed defined localization of CAP1/Prss8 in the granular layer of the human epidermis (Fig. 7) similar to CAP1/Prss8 expression in murine skin8. In healthy controls and acute dermatitis patients, CAP1/Prss8 was localized both intracellularly and at the plasma membrane. In patients with chronic and atopic dermatitis, CAP1/Prss8 appeared to be predominantly expressed at the plasma membrane. PAR2 expression was seen in suprabasal keratinocytes in the same samples and appeared to be more extensive in chronic and atopic dermatitis patients, following hyperplasia. It is thus conceivable that differential expression of CAP1/Prss8 and/or PAR2 in diseased versus healthy skin may contribute to the pathogenesis of these disorders.

Figure 7. Localization of CAP1/Prss8 and PAR2 in human epidermis.

Immunohistochemistry of CAP1/Prss8 and PAR2, both in green, in human skin sections. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). Bottom panel: parallel sections in which primary antibodies were omitted (negative control; No 1 Ab). The pictures are representative of biopsies analysed from two adult subjects with atopic dermatitis, five with acute dermatitis, three with chronic dermatitis and from four healthy controls. Dashed white lines represent epidermal/dermal junction. Scale bars represent 10 μm. BF: bright field.

Discussion

Altered activity of serine proteases4,7,8,10,37 and serine protease inhibitors5,9,38 can severely compromise skin homeostasis in mice and humans. In this study we used mouse models to demonstrate that increased expression of either the membrane-tethered serine protease CAP1/Prss8, or PAR2, a candidate downstream effector, is sufficient to induce skin disease in mice and that CAP1/Prss8-elicited pathogenesis is fully dependent on PAR2.

Transgenic K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice exhibited severe ichthyosis, hyperplasia, epidermal barrier defects and inflammation. Intriguingly, lack of one PAR2 allele associated with CAP1/Prss8 overexpression was sufficient to completely reverse the increased TEWL and body weight loss, but not ichthyosis and hyperplasia, suggesting that barrier dysfunction was not secondary to epidermal hyperplasia. Increased proliferation and TSLP production in primary keratinocytes isolated from K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice suggested that hyperplasia and inflammation were both, at least in part, directly triggered by a protease signalling cascade in keratinocytes, supporting a cell-autonomous phenotype. TSLP production by epithelial cells has been shown to trigger dendritic cell-mediated inflammation33, and it is well established that dendritic cells migrate from inflamed peripheral tissues to the closest draining lymph node to orchestrate adaptive immune responses39. PAR2 signalling was recently shown to promote dendritic cell trafficking to lymph nodes and subsequent T-cell activation40. In our K14-CAP1/Prss8 model, CD11c- and S100-positive dendritic cells were found to be more abundant in the skin, supporting a potential role for TSLP expression in immune cell recruitment and activation. Consistent with these findings, CAP1/Prss8 transgenic skin exhibited an increase in CD3-positive T cells, as demonstrated by both immunohistochemistry and FACS quantification. Taken together, these data suggest a possible CAP1/Prss8-PAR2-TSLP cascade in which TSLP, mobilized by CAP1/Prss8-elicited PAR2 activation on keratinocytes, stimulates dendritic cells that then recruit T cells to start an adaptive inflammatory response.

Increased scratching behaviour was documented in both Grhl3PAR2/+ knock-in and K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice. Itching sensation can be induced by dry, damaged and inflamed skin, and numerous epithelial and immune mediators can activate and sensitize sensory nerve endings and even modulate their growth (reviewed in ref. 41). However, there is also a body of evidence to suggest that PAR2 can function as a direct mediator of pruritus in humans20 and mice23. Functional PAR2 is present on primary spinal afferents42, and proteases might activate PAR2 on sensory nerves in the skin. Importantly, however, we aimed to drive PAR2 expression in epithelial cells, not in sensory nerves, and, as predicted from the expression pattern of Grhl3 (ref. 35), dorsal root ganglia or peripheral nerves are not targeted. Thus, although itching might increase lesion severity in older animals, and although neuronal PAR2 could be involved in itching sensation by paracrine activation of neuronal PAR2 in the CAP1/Prss8 model, itching did not appear to provoke the K14-CAP1/Prss8 and Grhl3PAR2/+ phenotypes.

Exploring a potential role for CAP1/Prss8 as an activator of PARs during neural tube closure, it was recently observed that CAP1/Prss8 was able to trigger PAR2-dependent signalling in a keratinocyte cell line. However, CAP1/Prss8 could not directly activate PAR2; it instead turned out that CAP1/Prss8-induced signalling in the systems studied was dependent on intermediate activation of the serine protease pro-CAP3/matriptase, which in turn was a remarkably potent and specific activator of PAR216. Constitutive CAP3/matriptase and skin-specific CAP1/Prss8 knockout mice exhibit similar phenotypes7,8,43 and CAP1/Prss8 was found exclusively in its inactive form in CAP3/matriptase/MT-SP1-deficient skin, demonstrating that CAP3/matriptase also activates CAP1/Prss8 in mouse skin. Hence, these findings strongly point to a more complex serine protease cascade, in which other components, such as additional serine proteases and serine protease inhibitors, could be involved. CAP3/matriptase has been found to be mutated in human autosomal recessive ichthyosis with hypotrichosis and ichthyosis in mice resulting from loss of function of HAI-1, a CAP3/matriptase inhibitor9,44, can be rescued with low CAP3/matriptase activity9. This indicates that excessive CAP3/matriptase activity can indeed lead to skin disease, and enhanced CAP1/Prss8 expression could well contribute to the phenotype. Whereas ablation of PAR2 from LEKTI-null animals inhibited prenatal production of TSLP, but not cutaneous inflammation in adulthood45, ablation of CAP3/matriptase from LEKTI-deficient mice substantially ameliorated the phenotype of this mouse model of Netherton syndrome46. Thus, CAP3/matriptase clearly has effectors other than PAR2. Furthermore, the phenotype of K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice differs from the K5-driven CAP3/matriptase overexpressing model10. Itching and severe skin lesions independent of tumour formations were not reported in K5-CAP3/matriptase transgenic mice10, and we never observed spontaneous tumour formation in CAP1/Prss8 transgenic animals, even when histopathologically followed up until their death. Finally, CAP1/Prss8 has been reported to have biological activity independent of its catalytic triad47,48; hence, we cannot exclude that CAP1/Prss8 elicits a protease cascade leading to PAR2 signalling by a cleavage-independent mechanism.

Besides functioning upstream of PAR2, as demonstrated here, CAP1/Prss8 is known to be involved in the activation of the highly amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel ENaC49. Complete ENaC knockout mice die postnatally because of impaired lung fluid clearance50 and exhibit dehydration similar to skin-specific CAP1/Prss8-deficient animals8,51. Other epidermal effectors of CAP1/Prss8 are filaggrin and occludin, both of which are processed normally in ENaC-deficient skin8,51. We therefore consider a contribution of ENaC to the K14-CAP1/Prss8-mediated skin phenotype as unlikely.

PAR2 has been implicated in inflammatory dermatosis17,52 and two natural mutations of CAP1/Prss8 have been found as causative of skin defects in rodents53. In human epidermis we found that CAP1/Prss8 expression, mainly in the granular layer, appeared more concentrated to the plasma membrane in affected skin from patients with atopic and chronic dermatitis relative to skin from healthy controls, and was accompanied by enhanced PAR2 expression in the epidermis of the same affected subjects. Observations in our transgenic models should prompt further investigation into whether CAP1/Prss8, its inhibitors, PAR2 and its other activators are deregulated in diseased human skin. K14-CAP1/Prss8 and Grhl3PAR2/+ mice may also serve as models to test the efficacy of protease inhibitors and/or PAR2 antagonists against ichthyosis, pruritus and inflammatory skin disorders.

Methods

Mice and primary cell culture

K14-CAP1/Prss8 transgenic mice were generated by cloning mouse CAP1/Prss8 cDNA (Genbank g.i. 19111159) into the pBHR2(SmaI) vector25,54 (See Supplementary Methods). The linearized vector was microinjected into B6D2F1 hybrid zygotes. Transgenic lines were maintained in the hemizygous state. Transgenic mice were genotyped by PCR and Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA extracted from tail biopsies55. Grhl3PAR2/+ knock-in mice were generated by targeting 129X1/SvJ-derived E14 ES cells using standard techniques, essentially as described for Grhl3Cre/+ mice16, except that Cre cDNA was replaced by mouse PAR2 cDNA. Further details of cloning are provided in Supplementary Information. The Grhl3PAR2/+ phenotype was observed in both C57BL6/J-129X1/SvJ mixed and FVB/n strain backgrounds. Mice from both strains were used for the experiments. Experimental procedures and animal maintenance followed federal guidelines and were approved by local authorities.

Mouse epidermal keratinocytes were isolated from pups and cultured in vitro56. Cell proliferation was quantified using the Quick Cell Proliferation Testing Solution (GenScript) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Measurement of scratching behaviour

For K14-CAP1/Prss8 mice and littermate controls, simultaneous experiments on three mice in three individual cages were conducted in the absence of investigators. Mice could not see each other during the experiment. The mice were videotaped for 15–20 min for later quantification of scratching behaviour. One scratch was considered as lifting of a limb towards the body with subsequent replacement of the limb on the bedding. For Grhl3PAR2/+ mice and littermate controls, mouse behaviour was recorded in the absence of investigators and the time spent grooming and/or scratching quantified in a 5 min time period and expressed as percentage of total time.

Immunofluorescence and histology

For paraffin-embedded sections: Slides were incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature following rinsing with PBS. Antigen retrieval was performed for 10 min in TEG buffer. Slides were washed in 50 mM NH4Cl in PBS for 30 min and blocked by 1% BSA, 0.2% gelatine, 0.05% Saponin in PBS at room temperature for 10 min, three times. Primary antibody was diluted in 0.1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies against keratin-14, keratin-1, keratin-6, involucrin, loricrin and filaggrin were purchased from Covance and diluted 1:1,000 or 1:4,000 (keratin-14). Affinity-purified CAP1/Prss8 rabbit anti-mouse antiserum57 was diluted 1:200. Rabbit polyclonal antibody PAR2 (H-99; sc-5597) was provided by Santa Cruz Biotechnology and diluted 1:1,000. Slides were rinsed three times for 10 min in PBS containing 0.1% BSA, 0.2% gelatine and 0.05% saponin at room temperature and the secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, diluted 1:5,000) was diluted in 0.1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS. Nuclei were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) 0.2 μg ml−1 in mounting media (Dako Schweiz AG). Staining was visualized using an LSM confocal microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.). For cryosections: Tissue-Tek O.C.T.-embedded skin was fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% SDS in PBS. After blocking with 2% BSA and 3% normal goat serum (NGS), sections were incubated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD3 antibody (555274, BD Pharmingen, diluted 1:100) for 1 h. LacZ staining: LacZ expression was detected by incubating the tissue at 30 °C overnight in 0.1% X-gal, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 1 mM magnesium chloride 0.002% NP-40, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, PBS, pH 7.0 (ref. 58). Giemsa: Paraffin sections were rehydrated and stained for several hours at 37 °C with standard Giemsa stain solution and subsequently rinsed in distilled water. The sections were differentiated with 0.5% aqueous acid acetic and rapidly dehydrated thereafter. For periodic acid Schiff staining: Paraffin sections were rehydrated, stained with periodic acid 0.5% for 10 min, washed and stained again with Schiff reagent for 5 min. After dehydration and xylene clearing, slides were mounted and visualized.

Horseradish peroxidase staining and TUNEL analysis

For horseradish peroxidase staining. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubating sections for 15 min in 1% H2O2/methanol. Sections were then boiled in 10 mM citrate (pH 6) for 15 min for antigen retrieval, rinsed in Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, and blocked with normal goat serum (1:10) for 5 min. Primary rat anti-mouse Ki67 (Dako M7249), rat anti-mouse F4/80 (Invitrogen MF48000) and S100 (Dako Z0311) antibodies were diluted 1:50, 1:20 and 1:1000, respectively, in Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 0.5% BSA and applied to sections for 1 h at room temperature. Following rinsing, specific binding was revealed by incubating with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rat polyclonal antibody (1:200) for 30 min and subsequent incubation with a 50-fold diluted HRP substrate (DAB; DAKO) for 7 min. Nuclei were counterstained using Harris haematoxylin. For TUNEL analysis: Following deparaffinization and rehydration, sections were pretreated with proteinase K (20 μg ml−1 in PBS, 30 min) at room temperature. PBS-rinsed sections were preincubated in TdT reaction buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 200 mM sodium cacodylate, 0.25 mg ml−1 BSA, 1 mM cobalt chloride) for 10 min and incubated for 1–2 h at 37 °C in a humidified chamber. The reaction was stopped by incubation with 300 mM NaCl and 30 mM sodium citrate for 10 min, and detection was performed with streptavidin-HRP in PBS for 20 min. Nuclei were counterstained with Gill's haematoxylin. Slides were dehydrated and covered with mounting medium. Positively stained cells were counted from three animals independently analysed per group. A minimum of three random pictures per section were taken using an Axion HRC (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.).

FACS analysis

Single cell suspensions were prepared from postnatal day-6 ventral skin31,32. After washing in PBS/5% FCS, the cells were stained for flow cytometry using standard procedures. The following monoclonal antibody conjugates were used to define cell subsets: CD45-Alexa 700 (30.H12), CD11c-APC (N4/18), CD3-PE (17A2), F4/80-APC-efluoro 780 and TCRVg3-FITC (536). All were purchased from eBioscience, except TCR Vg3-FITC, which was purchased from BD Pharmingen. DAPI (Invitrogen) was used for dead cell discrimination. Samples were analysed on an LSR II Flow Cytometer (Becton Dickinson) equipped with 488, 407 and 640 lasers and data analysed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Electron microscopy

Skin biopsy samples were minced to <0.5 mm3, fixed in modified Karnovsky's fixative overnight and postfixed in either 0.2% ruthenium tetroxide or 1% aqueous osmium tetroxide, containing 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide. After fixation, samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in an Epon–epoxy mixture. After selection of sites with perpendicular cross-sectioning in 1 mm toluidine blue-stained, epoxy-embedded sections, ultrathin sections were examined, with or without further contrasting with lead citrate, using a Zeiss 10A electron microscope (Carl Zeiss), operated at 60 kV.

Measurement of TEWL

The rate of TEWL from the ventral skin of preshaved, 2-week-old, anaesthetized transgenic and littermate controls was measured using a Tewameter TM210 (Courage and Khazaka)8. The mean±s.e.m. is shown.

Western blot analysis

Skin was homogenized using Tissue Lyzer (Qiagen) in 8 M urea, EDTA 10 mM, Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 8. Following 30 min incubation on ice, lysates were centrifuged (13,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C) and quantified using the Pierce BCA protein assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For SDS-PAGE, 50 μg proteins was loaded and separated on a 4–16% acrylamide gradient gel. Western blot analysis was performed using rabbit anti-mouse antibodies to K14 (1:10,000), K1, K6, filaggrin, loricrin and involucrin (1:1,000, Covance). Signals were revealed using anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G from donkey (1:2,000) as secondary antibody and the Pierce Fast Western Blot Kit SuperSignal West Dura (Thermo Fisher Scientific) detection system.

Tight junction functional assay

Junctional integrity of the epidermis was addressed by assessing diffusion of intradermally injected NHS-LC biotin8. Staining was visualized using an LSM confocal microscope after incubation of sections with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen) overnight at 4 °C. Nuclei were counterstained with 0.2 μg ml−1 DAPI (Roche) in mounting media (Dako Schweiz AG).

Semiquantitative and quantitative RT–PCR

Skin was homogenized using Tissue Lyzer (Qiagen) and RNA was extracted with the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit following the manufacturer's instructions. A volume of 1.5 μg of RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase and reverse transcribed using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase RNase H Minus Point Mutant (Promega). Real-time PCR was performed by TaqMan PCR using Applied Biosystems 7500. Each measurement was taken in triplicate. Quantification of fluorescence was normalized to β-actin. Amplified PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Lipid analyses

Whole skin from newborns was removed at autopsy, frozen and stored at −20 °C until further treatment. Stratum corneum lipids were homogenized, lyophilized and weighted. Epidermal lipids were extracted for 24 h at 37 °C in solvent mixtures (chloroform/methanol/water)59.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means±s.e.m. Individual groups were compared using the Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney test, except for lipid analyses for which the Welch Two Sample Student's t-test was applied. A level of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Author contributions

S.F. conducted most of the experiments. E.C. and S.R.C. designed and performed Grhl3PAR2/+ generation and characterization. G.C., S.R., M.M., R.-P.C., F.B., J.-C.S., B.B., K.S., S.R., A.W., M.H., S.R. and M.S. conducted and assisted in experiments. S.F., E.C. and E.H. wrote the manuscript. E.H. designed and supervised the study.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Frateschi, S. et al. PAR2 absence completely rescues inflammation and ichthyosis caused by altered CAP1/Prss8 expression in mouse skin. Nat. Commun. 2:161 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1162 (2011).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S2, Supplementary Table S1-S2 and Supplementary Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sabine Werner (ETH Zürich) for kindly providing the Keratin-14 promoter construct; Andrée Porret, Anne-Marie Mérillat, Sabrina Guichard and Heike Hupfer for excellent technical assistance; the members of the Hummler lab for discussions; and Bernard Rossier for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to the Mouse Pathology platform and the Cellular Imaging Facility platform, University of Lausanne. We thank Giancarlo Ramelli for help with PAR2−/− genotyping and Jean-Philippe Antonietti for help with the statistical analyses. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 3100A0-102125/1 to E. Hummler), by the German Research Foundation (DFG, SFB 645), by the seventh framework programme of the EU-funded 'LipidomicNet' (proposal number 202272) to K. Sandhoff and by the National Institutes of Health (S. Coughlin) and Inserm Avenir (E. Camerer).

References

- Meyer-Hoffert U. Reddish, scaly, and itchy: how proteases and their inhibitors contribute to inflammatory skin diseases. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 57, 345–354 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proksch E., Brandner J. M. & Jensen J. M. The skin: an indispensable barrier. Exp. Dermatol. 17, 1063–1072 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber M. et al. Mutations of keratinocyte transglutaminase in lamellar ichthyosis. Science 267, 525–528 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basel-Vanagaite L. et al. Autosomal recessive ichthyosis with hypotrichosis caused by a mutation in ST14, encoding type II transmembrane serine protease matriptase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 467–477 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descargues P. et al. Spink5-deficient mice mimic Netherton syndrome through degradation of desmoglein 1 by epidermal protease hyperactivity. Nat. Genet. 37, 56–65 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netzel-Arnett S. et al. Membrane anchored serine proteases: a rapidly expanding group of cell surface proteolytic enzymes with potential roles in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 22, 237–258 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K. et al. Matriptase/MT-SP1 is required for postnatal survival, epidermal barrier function, hair follicle development, and thymic homeostasis. Oncogene 21, 3765–3779 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyvraz C. et al. The epidermal barrier function is dependent on the serine protease CAP1/Prss8. J. Cell Biol. 170, 487–496 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo R., Kosa P., List K. & Bugge T. H. Loss of matriptase suppression underlies spint1 mutation-associated ichthyosis and postnatal lethality. Am. J. Pathol. 174, 2015–2022 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K. et al. Deregulated matriptase causes ras-independent multistage carcinogenesis and promotes ras-mediated malignant transformation. Genes Dev. 19, 1934–1950 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings N. D., Morton F. R., Kok C. Y., Kongand J. & Barrett A. J. MEROPS: the peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 320–325 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. X., Chao L. & Chao J. Prostasin is a novel human serine proteinase from seminal fluid. Purification, tissue distribution, and localization in prostate gland. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 18843–18848 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuagniaux G. et al. Activation of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel by the serine protease mCAP1 expressed in a mouse cortical collecting duct cell line. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 828–834 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heutinck K. M., ten Berge I. J., Hack C. E., Hamann J. & Rowshani A. T. Serine proteases of the human immune system in health and disease. Mol. Immunol. 47, 1943–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dery O., Corvera C. U., Steinhoff M. & Bunnett N. W. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel mechanisms of signaling by serine proteases. Am. J. Physiol. 274, C1429–1452 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camerer E. et al. Local protease signaling contributes to neural tube closure in the mouse embryo. Dev. Cell 18, 25–38 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M. et al. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 in human skin: tissue distribution and activation of keratinocytes by mast cell tryptase. Exp. Dermatol. 8, 282–294 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M. et al. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce inflammation by a neurogenic mechanism. Nat. Med. 6, 151–158 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpacovitch V. M. et al. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor 2 induce cytokine release and activation of nuclear transcription factor kappaB in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 118, 380–385 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M. et al. Proteinase-activated receptor-2 mediates itch: a novel pathway for pruritus in human skin. J. Neurosci. 23, 6176–6180 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derian C. K., Eckardt A. J. & Andrade-Gordon P. Differential regulation of human keratinocyte growth and differentiation by a novel family of protease-activated receptors. Cell Growth Differ 8, 743–749 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachem J.- P. et al. Serine protease signaling of epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 2074–2086 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada S. G., Shimada K. A. & Collins J. G. Scratching behavior in mice induced by the proteinase-activated receptor-2 agonist, SLIGRL-NH2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 530, 281–283 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea M. R. et al. Characterization of protease-activated receptor-2 immunoreactivity in normal human tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46, 157–164 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz B. et al. Overexpression of activin A in the skin of transgenic mice reveals new activities of activin in epidermal morphogenesis, dermal fibrosis and wound repair. EMBO J. 18, 5205–5215 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zettersten E. et al. Recessive x-linked ichthyosis: role of cholesterol-sulfate accumulation in the barrier abnormality. J. Invest. Dermatol. 111, 784–790 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering T. et al. Sphingolipid activator proteins are required for epidermal permeability barrier formation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 11038–11045 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold K. R. Thematic review series: skin lipids. The role of epidermal lipids in cutaneous permeability barrier homeostasis. J. Lipid Res. 48, 2531–2546 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. et al. RXR-alpha ablation in skin keratinocytes results in alopecia and epidermal alterations. Development 128, 675–688 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein M. R. Skin-limited Langerhans′ cell histiocytosis in children. Cancer Invest. 27, 504–511 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumortier A. et al. Atopic dermatitis-like disease and associated lethal myeloproliferative disorder arise from loss of notch signaling in the murine skin. PloS One 5, e9258 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero I., Wilson A., Beermann F., Held W. & MacDonald H. R. T cell receptor specificity is critical for the development of epidermal gammadelta T cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1473–1483 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumelis V. et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat. Immunol. 3, 673–680 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting S. B. et al. Inositol- and folate-resistant neural tube defects in mice lacking the epithelial-specific factor Grhl-3. Nat. Med. 9, 1513–1519 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting S. B. et al. A homolog of Drosophila grainy head is essential for epidermal integrity in mice. Science 308, 411–413 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner J. R. et al. Delayed onset of inflammation in protease-activated receptor-2-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 165, 6504–6510 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briot A. et al. Kallikrein 5 induces atopic dermatitis-like lesions through PAR2-mediated thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression in Netherton syndrome. J. Exp. Med. 206, 1135–1147 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavanas S. et al. Mutations in SPINK5, encoding a serine protease inhibitor, cause Netherton syndrome. Nat. Genet. 25, 141–142 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez D., Vollmann E. H. & von Andrian U. H. Mechanisms and consequences of dendritic cell migration. Immunity 29, 325–342 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramelli G. et al. Protease-activated receptor 2 signalling promotes dendritic cell antigen transport and T-cell activation in vivo. Immunology 129, 20–27 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhoff M. et al. Neurophysiological, neuroimmunological, and neuroendocrine basis of pruritus. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 1705–1718 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N., Ferazzini M., D′Andrea M. R., Buddenkotte J. & Steinhoff M. Proteinase-activated receptors: novel signals for peripheral nerves. Trends Neurosci. 26, 496–500 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- List K. et al. Loss of proteolytically processed filaggrin caused by epidermal deletion of Matriptase/MT-SP1. J. Cell Biol. 163, 901–910 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaike K. et al. Defect of hepatocyte growth factor activator inhibitor type 1/serine protease inhibitor, Kunitz type 1 (Hai-1/Spint1) leads to ichthyosis-like condition and abnormal hair development in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 1464–1475 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briot A. et al. Par2 inactivation inhibits early production of TSLP, but not cutaneous inflammation, in Netherton syndrome adult mouse model. J. Invest. Dermatol. 130, 2736–2742 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sales K. U. et al. Matriptase initiates activation of epidermal pro-kallikrein and disease onset in a mouse model of Netherton syndrome. Nat. Genet. 42, 676–683 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen D., Vuagniaux G., Fowler-Jaeger N., Hummler E. & Rossier B. C. Activation of epithelial sodium channels by mouse channel activating proteases (mCAP) expressed in Xenopus oocytes requires catalytic activity of mCAP3 and mCAP2 but not mCAP1. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 968–976 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Fu Y. Y., Lin C. Y., Chen L. M. & Chai K. X. Prostasin induces protease-dependent and independent molecular changes in the human prostate carcinoma cell line PC-3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1773, 1133–1140 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossier B. C. & Stutts M. J. Activation of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) by serine proteases. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 361–379 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummler E. et al. Early death due to defective neonatal lung liquid clearance in alpha-ENaC-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 12, 325–328 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles R. P. et al. Postnatal requirement of the epithelial sodium channel for maintenance of epidermal barrier function. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2622–2630 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buddenkotte J. et al. Agonists of proteinase-activated receptor-2 stimulate upregulation of intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 in primary human keratinocytes via activation of NF-kappa B. J. Invest. Dermatol. 124, 38–45 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spacek D. V. et al. The mouse frizzy (fr) and rat ′hairless′ (fr(CR)) mutations are natural variants of protease serine S1 family member 8 (Prss8). Exp. Dermatol. 19, 527–532 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wankell M. et al. Impaired wound healing in transgenic mice overexpressing the activin antagonist follistatin in the epidermis. EMBO J. 20, 5361–5372 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porret A., Merillat A. M., Guichard S., Beermann F. & Hummler E. Tissue-specific transgenic and knockout mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 337, 185–205 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone A., Hagerand B. & Fleckman P. Primary mouse keratinocyte culture. Methods Mol. Biol. 289, 3–14 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planes C. et al. In vitro and in vivo regulation of transepithelial lung alveolar sodium transport by serine proteases. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 288, 1099–1109 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaeger T. M., Qin Y., Fujiwara Y., Magramand J. & Sato T. N. Vascular endothelial cell lineage-specific promoter in transgenic mice. Development 121, 1089–1098 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichelt J., Breiden B., Sandhoff K. & Magin T. M. Loss of keratin 10 is accompanied by increased sebocyte proliferation and differentiation. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 83, 747–759 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S2, Supplementary Table S1-S2 and Supplementary Methods.