Abstract

Tests for immunoglobulin reactivity with specific antigens are some of the oldest and most used assays in immunology. With efforts to understand B cell development, B cell dysregulation in autoimmunity, and to generate B cell vaccines for infectious agents, investigators have found the need to understand the ontogeny and regulation of epitope-specific B cell responses. The synchrony between surface and secreted antibodies for individual B cells has led to the development of reagents and techniques to identify antigen-specific B cells via reagent interactions with the B cell receptor complex. B cell antigen-specific reagents have been reported for model systems of haptens, for whole proteins, and for identification of double stranded (ds) DNA antibody-producing B cells using peptide mimics. Here we provide an overview of reported techniques for the detection of antigen-specific B cell responses via secreted antibody or by the surface B cell receptor and briefly discuss our recent work developing a panel of reagents to probe the B cell response to HIV-1 envelope. We also present an analysis of strengths and weaknesses of various methods for flow cytometric analysis of antigen-specific B cells.

Keywords: B cells, HIV-1 Envelope, tetramers, antibodies

Introduction

The finding of serum antibodies capable of highly-specific recognition of foreign molecules revolutionized medicine (1). The development of antitoxin by von Behring (2) and the subsequent investigations of antitoxins by Ehrlich (3) formed the basis for the diagnostic and therapeutic uses of antibodies. The practical utilization of their discoveries led to the widespread use of therapeutic immune globulins (e.g., diphtheria and tetanus anti-toxins), serological tests for diseases (e.g., the Wasserman test for syphilis)(4), and polyclonal detection reagents (e.g., anti-immunoglobulin reagents)(5). Improvements in the use of antibodies as diagnostics and therapeutics were incremental until Köhler and Milstein described the production of murine monoclonal antibodies by hybridoma formation techniques (6). With the widespread application of this method, an explosion in monoclonal antibody (mAb) reagents followed, and a standard nomenclature for immune cell differentiation markers was developed that allowed for greater understanding of the networks involved in normal and aberrant immune cell function (7,8)

At each stage of the development of antibodies as diagnostic and therapeutic reagents has come investigation of the function of B cells in humans and animal model systems. Since the time of von Behring and Ehrlich, the study of B cells has been both a means and an end; the exquisite specificity of antibodies has been used to probe the immune system in an effort to understand immunobiology while the functional nature of antibodies has been used in the development of therapeutic drugs and diagnostic tests (1). Antibodies as probes are embedded in the language of immunology as clusters of differentiation (CD) used to characterize cells of the immune system (7). Functional antibodies continue to be used today as equine serum products for the treatment of toxin-mediated disease, as purified gammaglobulin for prevention and treatment of disease, and as monoclonal antibodies to treat specific diseases or to modulate the immune system. The duality of antibodies as probes and as functional agents is evident in the use of immunization by immunologists and vaccinologists who immunize and monitor antibody responses both to probe aspects of the immune system and as a method for inducing a protective effect in an immunized host. Nearly all protective vaccines produce a robust antibody response that correlates with the degree of protection afforded by the vaccine (9). Immunogens vary and include inactivated toxins, live and attenuated whole organisms, organism subunits, and antigenic determinants coupled to carrier molecules. These vaccines produce protective antibodies of high titer that are long-lived (10).

To develop the currently approved successful preventative vaccines such as for measles, mumps, rubella, polio, and tetanus, emperical approaches were successful. Unfortunately, empirical approaches to make HIV-1 toxoids (11,12), live attenuated (13), killed whole virus (14,15), vectored (16), and protein subunit-based (17,18) have failed to produce an effective vaccine against HIV-1—a virus that infects over 10,000 people each day (19). Intensive effort has been placed on the development of a recombinant adenovirus type 5 (rAd5) T cell-based vaccine for HIV-1, but the results of a recent large efficacy trial not only failed to show any protective effect of the vaccine but showed probable enhanced acquisition of HIV-1 infection in those with preexisting immunity to the rAd5 vector (16). That antibodies could have a protective role against HIV-1 is suggested by non-human primate trials of passively administered antibodies that have prevented infection from mucosal and blood-borne challenge with simian-human immunodeficiency chimeric viruses (SHIVs) (20,21). Antibodies that broadly neutralize HIV-1 across clades are rarely made and in some cases are polyreactive with host antigens (22). Many of these antibodies are also structurally unusual such as having long, hydrophobic complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3) loops as is seen with 2F5 (23), 4E10 (24), and b12 (25), or having a domain-swapped dimeric structure as seen with 2G12 (26). Possibilities for why broadly reactive antibodies against the HIV-1 envelope are rare include glycan shielding as up to 40% of the mass of HIV-1 envelope can be carbohydrate (27) and flexibility of the envelope and entropic barriers to binding of B cell receptor (BCR)-associated and free serum immunoglobulin (28). The membrane proximal external region (MPER) of gp41 is vulnerable to the broadly reactive mAbs 2F5 and 4E10, however this region of the envelope is involved in the cell fusion process and may only be transiently exposed (29) thus not allowing the BCR or free antibody time to interact. Finally, many of the vulnerable sites on the envelope may be covered, either by conformational masking (28) or in the case of the MPER buried in virion lipids (30-33). Thus, one part of the problem may be with envelope presentation to the immune system—this problem would be solved by defining constrained structures that would overcome limits to epitope availability to the BCR (34). Another part of the problem may be the mode of immunoregulation of B cells capable of responding to envelope—this problem would be solved by understanding the pool of origin and the regulation of B cells capable of making broadly neutralizing antibodies (35). To test these hypotheses, HIV-1 envelope antigen-specific B cell reagents are needed to probe the B cell repertoire.

Study of Secreted Antibodies

Regardless of isotype, all antibodies share a common structure, including a constant region that can bind to specific cell surface receptors and complement, and a variable region that is responsible for antigen-specific binding. The variable region is further divided into structural protein and an antigen recognition site. This site is created by pairing heavy and light chains each of which contribute three complementarity determining regions (CDRs) to create the binding pocket. The genetic machinery used to create CDRs results in profound diversity with an estimated 1010-1014 specificities of antibodies that can be created (36). All antibody isotypes have at least two antigen recognition sites per molecule; since each site can bind to its own antigen, antibodies have the ability to form immune complexes.

One of the great advances in immunology was the harnessing of the immune response to detect antibodies themselves. Antibodies from one species administered to a different host tend to generate an intense immune response, seen clinically as serum sickness following delivery of equine antitoxins. This response has been used to generate reagents that recognize antibodies from many different species and permits a wide variety of assays including enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (5).

The enzyme linked immunospot (ELISPOT) technique is a way to study secreted antibody but at a cellular level (37,38). Although now used commonly for analysis of T cell production of cytokines (39-41), the technique was first described for detecting antigen-specific B cells. ELISPOT assays permit quantitation of antigen-specific B cells and form a bridge between the study of secreted antibodies and the study of individual B cells.

A novel method for the study of B cells at the cellular level was recently described by Tokimitsu, et al. (42) and by Tajiri, et al. (43). Through the use of microfabrication techniques, they created arrays of microwells that they loaded with single lymphocytes. After loading, they probed the cells by different techniques and linked the data back to individual cells. They were also able to detect B cells reactive with hepatitis B surface antigen and make monoclonal antibodies from individual cells. Although the equipment costs are likely out of the range of many investigators, this method shows promise as it enables the use of existing assays to probe individual cells.

Study of B Cells via the BCR

B cells produce both secreted antibody and a membrane bound form as part of the B cell receptor (BCR) complex. Surface and secreted immunoglobulin from individual cells has been studied by the use of antigen-specific labeling and flow cytometric analysis (44). The monospecificity of surface immunoglobulin on individual B cells was established by the same technique (45). Since the discovery of the BCR, many investigators have used surface antibody both to label and to sort B cells for investigation.

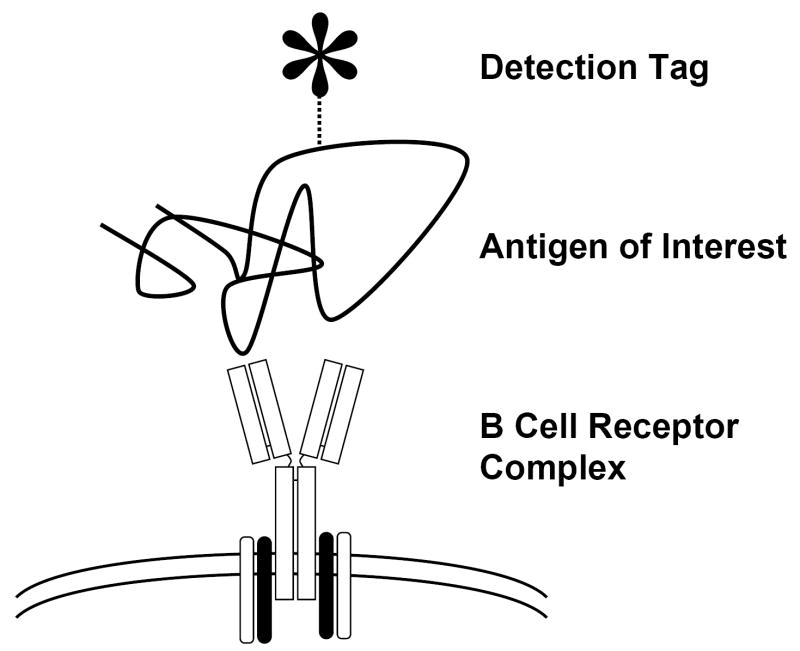

Techniques reported using antigen-specific reagents for the detection of B cells via the BCR have fallen into three broad categories: haptens on carriers, labeled proteins or whole virions/organisms, and epitopes presented by a display system (see Table 1). Regardless of the reagent type, the desired interaction is that of the antigen of interest with the cell surface BCR (Fig. 1). In each case, a fluorochrome, biotin, or other detection reagent is used to label or capture the cell by using the cell surface bound immune complex.

Figure 1.

Haptens are small molecules, such as dinitrophenol or trinitrophenol, to which the immune system generally does not respond but that can elicit a specific response when the molecule is attached to an immunogenic protein carrier. These small molecules are not present in antigens from host animals or infectious agents and allow investigators to detect responses that can only be stimulated by the hapten-carrier system. Haptens have been used mostly to probe aspects of B cell biology in model systems in mice (45-50). The design of these studies has generally been such that the existence of a population answered the question being asked. While very useful in probing the immune system, the absence of these molecules in native antigens limits their utility in studying HIV-1 or other infectious diseases.

Whole protein and whole organism approaches have been used for the study of model systems (44,45,51,52), but they have also been used for the study of responses to pathogens and vaccines (42,43,53). Since these reagents detect B cells reactive with whole proteins or whole virions, they are subject to many more confounders than hapten systems. The advantage is that antigen epitopes are presented in the context of a whole protein or organism, thus maintaining discontinuous or conformational epitopes that may not be available via epitope specific systems. As non-relevant epitopes may also be present, the B cells selected by such reagents may represent a range of epitopes only some of which are of interest. For whole virion reagents the presence of additional antigens including envelope lipids, embedded host molecules, and host-applied antigen modifications can increase the background of irrelevant epitopes detected.

Epitope display systems offer one way to address some of these concerns. Using a biotinylated epitope peptide that inhibited a pathogenic dsDNA antibody, Newman, et al. described a system where that peptide was reacted with fluorochrome-labeled streptavidin and was subsequently used to detect antigen-specific cells in immunized mice (54). We have now extended this technique to a range of epitopes for HIV-1 envelope to study potential immunoregulatory controls in the production of broadly reactive neutralizing antibodies (Moody, et al. submitted). In order to understand the rarity of certain responses we have prepared a panel that includes epitopes that commonly induce antibody responses such as the gp120 V3 loop as well as those that rarely induce broadly reactive antibodies such as the gp41 MPER. The B cell tetramer technique avoids the problem of irrelevant epitopes due to whole antigenic protein but introduces that of reactivity against streptavidin itself. The diversity of the antibody repertoire is such that B cells reactive with streptavidin are expected and constitute an unavoidable background. In our hands, the background due to this system ranges from 8-60% depending on the epitope displayed.

An additional source of background for all fluorescently-labeled reagents is the detection tag itself. Fluorochromes range in size from small molecules of 1000 Da to phycoerythrin at 240,000 Da. The diversity of the antibody repertoire means that some antibodies specific for fluorochrome are likely present and would be labeled by detection reagents. Although this property was harnessed for the detection of phycoerythrin reactive B cells (52), in other contexts it represents another contributor to background that must be taken into account.

In their excellent paper, Kodituwakku, et al. noted two problems with the techniques they reviewed for the detection and sorting of antigen-specific B cells by flow cytometric and other techniques (55). First, most methods of determining the purity of isolated cells were identical or nearly identical to the method used for purifying the cells; Kodituwakku, et al. noted that the use of the same technique for both purification and post-purification analysis does not truly verify purity. Second, the methods that have been reported all yielded impure populations of cells, regardless of the technique employed or the analysis method used. To overcome the first problem requires the use of alternative analysis techniques distinct from those used to purify cells, such as ELISPOT assays or sequencing of immunoglobulin genes. In future there may be new assays and techniques developed to attack this problem. Overcoming the second problem is not straightforward because of background due to carrier proteins, irrelevant epitopes in complex antigens, and fluorochromes. As we have noted, all parts of a complex detection reagent, such as irrelevant epitopes of a whole protein antigen or epitopes present on a carrier protein, have the potential to increase the background of the method or to decrease the final purity of sorted cells.

One way to deal with background due to fluorochrome binding is to use dual antigen-specific labeling (56). Townsend, et al. reported using both fluorescein and phycoerythrin labeled antigen in order to detect very small populations of antigen specific cells. By only selecting for the cells labeled by both fluorochromes they were able to reduce the selection of non-specific cells by flow cytometry. Such a system will allow for the reduction of background due to fluorochrome binding, but if the carrier protein remains constant it will not eliminate background due to that.

Other Confounding Variables

As with the detection of any population of cells with a very low frequency, the problems of non-specific binding and noise inherent in the detection systems become greater as the signal being sought decreases in intensity. Dual labeling offers an attractive way to enrich the selection of antigen-specific cells but is not without its own set of problems. If the two detection reagents possess differential affinity then some cells may bind one of the reagents more than the other and would then be lost using a dual labeling system system. In fact, the difference need not be large and could come from either on- or off-rate. Thus dual labeling could skew selection for antibodies of a particular type while eliminating others that could be of interest.

Many labeling protocols involve the staining of cells from whole blood before the removal of serum proteins. If a host has a circulating high titered antibody present in the serum, those antibodies could form immune complexes with the detection reagent and could reduce or eliminate binding to the BCR. Although not reported, it is also possible that the binding of antigen-specific reagents and circulating antibodies could form a nidus for the deposition of complement and induce damage to those cells of most interest. For this reason we perform our work on cells after the removal of serum proteins, usually by density gradient separation. The isolation of cells by such methods can induce its own set of confounders by altering populations of cells remaining and represents another unavoidable compromise.

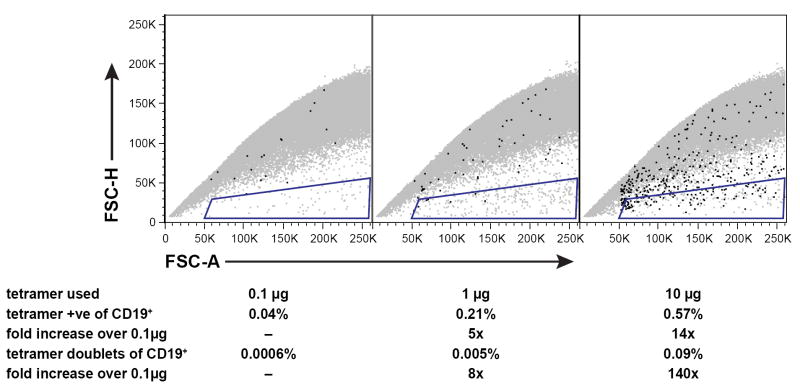

Even in the absence of serum protein, the cross-linking of antibody by antigen-specific reagents is possible via the BCR itself. It is known that cross-linking of the BCR can induce capping and internalization of those complexes by metabolically active B cells (57,58). We have observed that in some circumstances, and especially at very high titers of antigen-specific reagents, whole cells can be cross-linked and can appear as doublets in flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 2, methods available as supplemental online material). Although these can be eliminated electronically by gating, the presence of such aggregates can reduce the numbers of cells present for final analysis. For this reason we recommend that each reagent be studied to determine the threshold at which such aggregates occur and to use the reagents below that threshold.

Figure 2.

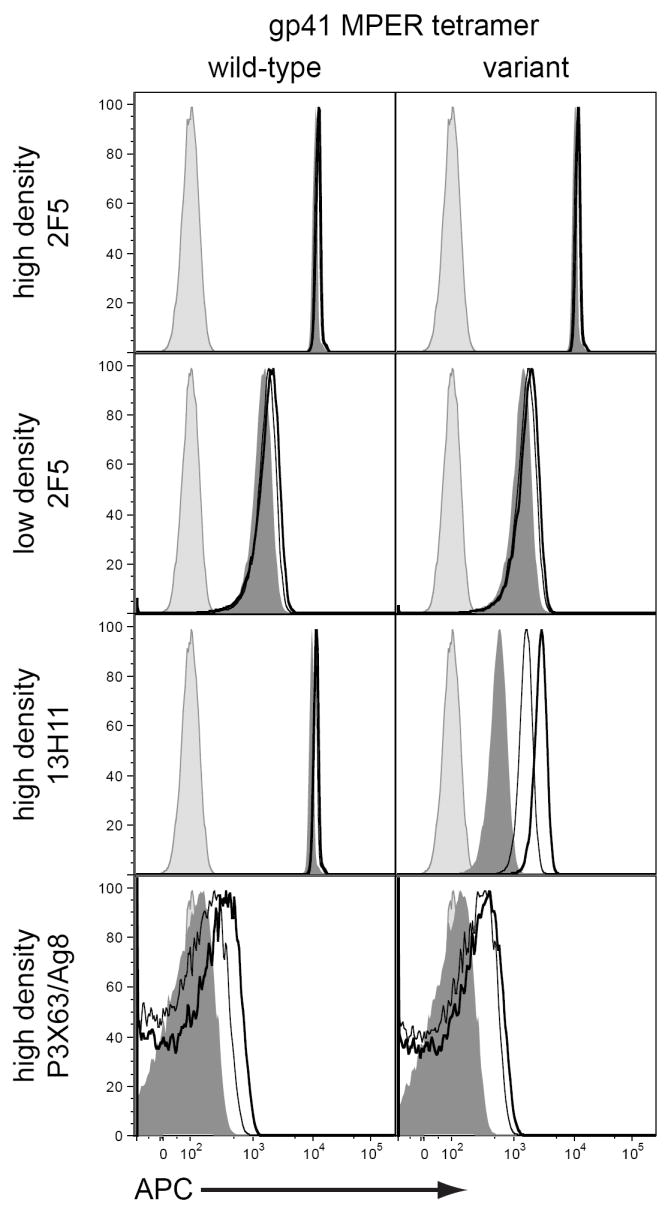

When small populations are being analyzed, a balance between yield and stringency of selection must be considered. It is tempting to use the highest amount of reagent possible and to take only the most strongly labeled cells for analysis. Unfortunately, as we have noted increasing amounts of reagent can have undesired effects. Furthermore, cells that have been labeled more brightly may not represent the desired population. The degree of staining will be affected by the degree of surface BCR present and the affinity of the surface antibody for the antigen being detected. As we show in Figure 3, under the right conditions a low density-high affinity antibody can have the same fluorescence staining as a high density-low affinity antibody (methods available as supplemental online material). Given the diversity of the B cell repertoire, surface antibodies of different affinities are expected. It is, therefore, possible that cells minimally above background could have a very high affinity antibody but have very low BCR expression as is seen on cells transitioning to become plasmacytes (59). Thus, the degree of selection stringency must be considered for every experiment depending on the question being asked.

Figure 3.

Finally, unlike the T cell arm of the immune system, where functional cells both circulate and maintain their expression of T cell receptors, mature B cells that are destined to become plasmacytes both downregulate BCR expression and home to lymphoid organs. B cells that have undergone antigen drive and that produce high affinity antibodies are thought to be those cells that ultimately become plasmacytes and so this represents a dual dilemma for investigators. For human work, the collection of peripheral blood is easier than the collection of lymphoid tissues such as bone marrow, tonsil, and spleen; thus the detection of antigen-specific B cell responses may be at a disadvantage. In addition, all of the techniques described use the presence of surface BCR for detection and so would be useless in the study of plasma cells. Intracellular staining protocols that would allow for the detection of plasma cells could be used, but these methods usually render the cells non-functional for downstream assays. The development of techniques for addressing this problem is an area of active research in our own and other laboratories.

Conclusions

The use of methods for the detection of B cells via the BCR using antigen-specific reagents has allowed the investigation of many questions related to B cell responses to infectious agents and in the setting of autoimmune disease. These techniques offer great promise in the investigation of vaccine trials for HIV-1 where the induction of long-lived and broad antigen-specific B cell responses has been challenging. Development of new antigen-specific reagents and methods will require close collaboration among immunologists and structural biologists to permit the presentation of epitopes in contexts where they can be detected by the BCR. Although many confounding variables are inherent in these techniques, a deeper understanding of these variables will permit quantitation of human B cell immunity, and may aid in vaccine immunogen design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Mark S. Drinker and Thaddeus C. Gurley who performed the flow experiments shown in this paper. We thank Marc C. Levesque, Laurent K. Verkoczy, and Garnett Kelsoe for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Center for HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology Grant, AI0678501, by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases P01 AI52816, AI51445, and a Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement The authors declare that they have filed a patent for technology related to antigen-specific B cell detection reagents.

References

- 1.Llewelyn MB, Hawkins RE, Russell SJ. Discovery of antibodies. BMJ. 1992;305(6864):1269–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6864.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacNalty AS. Emil von Behring, born March 15, 1854. BMJ. 1954;1(4863):668–70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4863.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dale H. Paul Ehrlich, born March 14, 1854. BMJ. 1954;1(4863):659–63. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4863.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasserman A, Neisser A, Bruck C. Eine serodiagnostische Reaktion bei Syphilis. Deutsche medizinische Wochenschrift. 1906;32:745–746. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engvall E, Perlmann P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry. 1971;8(9):871–874. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Köhler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256(5517):495–7. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard A, Boumsell L, Dausset J, Milstein C, Schlossman SF, editors. Leucocyte typing: human leucocyte differentiation antigens detected by monoclonal antibodies: specification, classification, nomenclature. xxiv. Berlin ; New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984. p. 814. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinherz EL, Haynes BF, Nadler LM, Bernstein ID, editors. Leukocyte typing II. Volume 2: Human B lymphocytes. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plotkin SA. Immunologic correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2001;20(1):63–75. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of Humoral Immunity to Common Viral and Vaccine Antigens. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(19):1903–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauza CD, Trivedi P, Wallace M, Ruckwardt TJ, Le Buanec H, Lu W, Bizzini B, Burny A, Zagury D, Gallo RC. Vaccination with Tat toxoid attenuates disease in simian/HIV-challenged macaques. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(7):3515–3519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070049797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silvera P, Richardson MW, Greenhouse J, Yalley-Ogunro J, Shaw N, Mirchandani J, Khalili K, Zagury J-F, Lewis MG, Rappaport J. Outcome of Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus Strain 89.6p Challenge following Vaccination of Rhesus Macaques with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Tat Protein. Journal of Virology. 2002;76(8):3800–3809. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3800-3809.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baba TW, Liska V, Khimani AH, Ray NB, Dailey PJ, Penninck D, Bronson R, Greene MF, McClure HM, Martin LN, et al. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nature Medicine. 1999;5(2):194–203. doi: 10.1038/5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaCasse RA, Follis KE, Trahey M, Scarborough JD, Littman DR, Nunberg JH. Fusion-competent vaccines: broad neutralization of primary isolates of HIV. Science. 1999;283(5400):357–62. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nunberg JH. Retraction. Science. 2002;296(5570):1025. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5570.1025b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekaly R-P. The failed HIV Merck vaccine study: a step back or a launching point for future vaccine development? Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205(1):7–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitisuttithum P, Berman PW, Phonrat B, Suntharasamai P, Raktham S, Srisuwanvilai L-O, Hirunras K, Kitayaporn D, Kaewkangwal J, Migasena S, et al. Phase I/II Study of a Candidate Vaccine Designed Against the B and E Subtypes of HIV-1. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;37(1):1160–1165. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000136091.72955.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.VanCott TC, Bethke FR, Burke DS, Redfield RR, Birx DL. Lack of induction of antibodies specific for conserved, discontinuous epitopes of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein by candidate AIDS vaccines. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(8):4100–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.anonymous. Global situation of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, end 2004. Weekly Epidemiological Record. 2004;79(50):441–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascola JR, Stiegler G, VanCott TC, Katinger H, Carpenter CB, Hanson CE, Beary H, Hayes D, Frankel SS, Birx DL, et al. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(2):207–10. doi: 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baba TW, Liska V, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Vlasak J, Xu W, Ayehunie S, Cavacini LA, Posner MR, Katinger H, Stiegler G, et al. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nature Medicine. 2000;6(2):200–6. doi: 10.1038/72309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Robinson J, Scearce RM, Plonk K, Staats HF, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308(5730):1906–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwick MB, Komori HK, Stanfield RL, Church S, Wang M, Parren PW, Kunert R, Katinger H, Wilson IA, Burton DR. The long third complementarity-determining region of the heavy chain is important in the activity of the broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5. Journal of Virology. 2004;78(6):3155–61. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.3155-3161.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cardoso RM, Zwick MB, Stanfield RL, Kunert R, Binley JM, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibody 4E10 recognizes a helical conformation of a highly conserved fusion-associated motif in gp41. Immunity. 2005;22(2):163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saphire EO, Parren PWHI, Pantophlet R, Zwick MB, Morris GM, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Crystal Structure of a Neutralizing Human IgG Against HIV-1: A Template for Vaccine Design. Science. 2001;293(5532):1155–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1061692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, Deechongkit S, Mimura Y, Kunert R, Zhu P, Wormald MR, Stanfield RL, Roux KH, et al. Antibody Domain Exchange Is an Immunological Solution to Carbohydrate Cluster Recognition. Science. 2003;300(5628):2065–2071. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, et al. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422(6929):307–12. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, et al. HIV-1 evades antibody-mediated neutralization through conformational masking of receptor-binding sites. Nature. 2002;420(6916):678–82. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barbato G, Bianchi E, Ingallinella P, Hurni WH, Miller MD, Ciliberto G, Cortese R, Bazzo R, Shiver JW, Pessi A. Structural analysis of the epitope of the anti-HIV antibody 2F5 sheds light into its mechanism of neutralization and HIV fusion. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;330(5):1101–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00611-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. Journal of Virology. 2004;78(19):10724–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10724-10737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun ZY, Oh KJ, Kim M, Yu J, Brusic V, Song L, Qiao Z, Wang JH, Wagner G, Reinherz EL. HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody extracts its epitope from a kinked gp41 ectodomain region on the viral membrane. Immunity. 2008;28(1):52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu P, Liu J, Bess J, Jr, Chertova E, Lifson JD, Grise H, Ofek GA, Taylor KA, Roux KH. Distribution and three-dimensional structure of AIDS virus envelope spikes. Nature. 2006;441(7095):847–52. doi: 10.1038/nature04817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burton DR, Desrosiers RC, Doms RW, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Moore JP, Nabel GJ, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt RT. HIV vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nature Immunology. 2004;5(3):233–236. doi: 10.1038/ni0304-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haynes BF, Moody MA, Verkoczy L, Kelsoe G, Alam SM. Antibody polyspecificity and neutralization of HIV-1: A hypothesis. Human Antibodies. 2005;14(3-4):59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanz I. Multiple mechanisms participate in the generation of diversity of human H chain CDR3 regions. Journal of Immunology. 1991;147(5):1720–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sedgwick JD, Holt PG. A solid-phase immunoenzymatic technique for the enumeration of specific antibody-secreting cells. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1983;57(1-3):301–309. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Czerkinsky CC, Nilsson L-A, Nygren H, Ouchterlony O, Tarkowski A. A solid-phase enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay for enumeration of specific antibody-secreting cells. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1983;65(1-2):109–121. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olive D, Autran B, Robinet E, Consortium AIB. The ELISPOT assay - quality issues related to its use in a multicenter setting. Cytometry. 2008 THIS ISSUE. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Precopio ML, Butterfield TR, Casazza JP, Koup RA, Roederer M. Optimization of T cell epitope identification. Cytometry. 2008 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20646. THIS ISSUE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Pira G, Ivaldi F, Dentone C, Righi E, Del Bono V, Viscoli C, Manca F. Miniaturization and automation for measuring antigen specific T-cell responses. Cytometry. 2008 doi: 10.1128/CVI.00322-08. THIS ISSUE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tokimitsu Y, Kishi H, Kondo S, Honda R, Tajiri K, Motoki K, Ozawa T, Kadowaki S, Obata T, Fujiki S, et al. Single lymphocyte analysis with a microwell array chip. Cytometry A. 2007;71(12):1003–10. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tajiri K, Kishi H, Tokimitsu Y, Kondo S, Ozawa T, Kinoshita K, Jin A, Kadowaki S, Sugiyama T, Muraguchi A. Cell-microarray analysis of antigen-specific B-cells: single cell analysis of antigen receptor expression and specificity. Cytometry A. 2007;71(11):961–7. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Julius MH, Masuda T, Herzenberg LA. Demonstration that Antigen-Binding Cells are Precursors of Antibody-Producing Cells after Purification with a Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1972;69(7):1934–1938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.7.1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Julius MH, Janeway CA, Jr, Herzenberg LA. Isolation of antigen-binding cells from unprimed mice. II. Evidence for monospecificity of antigen-binding cells. European Journal of Immunology. 1976;6(4):288–292. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830060410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greenstein JL, Leary J, Horan P, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Flow sorting of antigen-binding B cell subsets. Journal of Immunology. 1980;124(3):1472–1481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McHeyzer-Williams MG, Nossal GJV, Lalor PA. Molecular characterization of single memory B cells. Nature. 1991;350(6318):502–505. doi: 10.1038/350502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lalor PA, Nossal GJV, Sanderson RD, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Functional and molecular characterization of single, (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl (NP)-specific, IgG1+ B cells from antibody-secreting and memory B cell pathways in the C57BL/6 immune response to NP. European Journal of Immunology. 1992;22(11):3001–3011. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Cool M, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific B Cell Memory: Expression and Replenishment of a Novel B220− Memory B Cell Compartment. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191(7):1149–1166. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blink EJ, Light A, Kallies A, Nutt SL, Hodgkin PD, Tarlinton DM. Early appearance of germinal center-derived memory B cells and plasma cells in blood after primary immunization. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201(4):545–554. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoven MY, De Leij L, Keij JFK. The TH. Detection and isolation of antigen-specific B cells by the fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) Journal of Immunological Methods. 1989;117(2):275–284. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayakawa K, Ishii R, Yamasaki K, Kishimoto T, Hardy RR. Isolation of high-affinity memory B cells: phycoerythrin as a probe for antigen-binding cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84(5):1379–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doucett VP, Gerhard W, Owler K, Curry D, Brown L, Baumgarth N. Enumeration and characterization of virus-specific B cells by multicolor flow cytometry. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2005;303(1-2):40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Newman J, Rice JS, Wang C, Harris SL, Diamond B. Identification of an antigen-specific B cell population. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2003;272(1-2):177–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00499-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kodituwakku AP, Jessup C, Zola H, Roberton DM. Isolation of antigen-specific B cells. Immunology & Cell Biology. 2003;81(3):163–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Townsend SE, Goodnow CC, Cornall RJ. Single epitope multiple staining to detect ultralow frequency B cells. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2001;249(1-2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unanue ER, Perkins WD, Karnovsky MJ. Ligand-induced movement of lymphocyte membrane macromolecules. I. Analysis by immunofluorescence and ultrastructural radioautography. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1972;136(4):885–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.4.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Splinter TA, Collard JG, De Wildt A, Temmink JH, Décary F. Capping of surface immunoglobulin on ‘hairy cells’ is independent of energy production. Journal of Cell Science. 1979;36:45–59. doi: 10.1242/jcs.36.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radbruch A, Muehlinghaus G, Luger EO, Inamine A, Smith KG, Dörner T, Hiepe F. Competence and competition: the challenge of becoming a long-lived plasma cell. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2006;6(10):741–50. doi: 10.1038/nri1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alam SM, McAdams M, Boren D, Rak M, Scearce RM, Gao F, Camacho ZT, Gewirth D, Kelsoe G, Chen P, et al. The Role of Antibody Polyspecificity and Lipid Reactivity in Binding of Broadly Neutralizing Anti-HIV-1 Envelope Human Monoclonal Antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to Glycoprotein 41 Membrane Proximal Envelope Epitopes. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(7):4424–4435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Virology. 1993;67(11):6642–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.